Abstracts

Abstract

This article reflects on the divergences between translated and non-translated texts, and the specificities of fictional dialogue in audiovisual texts. Research suggests that audiovisual dialogue consists of a combination of linguistic features used in speech and writing, and that both translators and scriptwriters should aim to achieve a balance of these features to create spontaneous-sounding dialogues. Working with an audiovisual corpus of domestic and dubbed sitcoms in Spanish (Siete Vidas and Friends respectively), the purpose of this article is to provide an overview of how Spanish dialogues are shaped from a linguistic point of view across all language levels, highlighting the trends identified in their production and their translation in order to compare them. The results reveal the complex relationship established between speech and writing in audiovisual texts, and disclose the resources used by translators and scriptwriters to carefully plan dialogues which sound credible. Findings also suggest that domestic audiovisual texts bear more resemblance to spontaneous conversation than dubbed texts.

Keywords:

- audiovisual translation,

- dubbing,

- dubbese,

- fictional dialogue,

- prefabricated orality

Résumé

Cet article examine les divergences qui existent entre les textes traduits et les textes non traduits ainsi que les spécificités du dialogue fictionnel dans les textes audiovisuels. Certains travaux de recherche suggèrent que le dialogue audiovisuel est constitué d’un ensemble de caractéristiques linguistiques utilisées à l’oral et à l’écrit, et que les traducteurs ainsi que les scénaristes devraient viser à atteindre un équilibre entre ces caractéristiques pour créer des dialogues qui soient spontanés. Cet article s’appuie sur un corpus audiovisuel comprenant une comédie de situation (sitcom) en langue originale (Siete Vidas) et une autre doublée en espagnol (Friends), afin d’offrir une vue d’ensemble sur la façon dont les dialogues espagnols sont formés d’un point de vue linguistique à tous les niveaux de la langue. Nous présentons les tendances qui ont été identifiées dans la production et la traduction de ces dialogues afin de les comparer. Les résultats révèlent qu’une relation complexe s’établit entre parole et écriture dans les textes audiovisuels et nous exposons les ressources utilisées par les traducteurs et les scénaristes pour créer des dialogues qui soient crédibles. Les résultats suggèrent aussi que les textes audiovisuels en langue originale ont plus de ressemblance avec les conversations spontanées que les textes doublés.

Mots-clés :

- traduction audiovisuelle,

- doublage,

- dubbese,

- dialogue fictionnel,

- oralité préfabriquée

Article body

1. Introduction

At the present time, it seems to be widely acknowledged that the linguistic patterning of domestic and dubbed fictional dialogues differs significantly. Some authors even consider that distinguishing between a domestic and a dubbed production is uncomplicated, and that viewers can often make this distinction without any issues (Whitman-Linsen 1992; Herbst 1997; Pérez-González 2007). In the field of audiovisual translation, several scholars have explored the characteristics of dubbese (Myers 1973), or the specific register of dubbed texts, and have highlighted its differences when compared to non-translated or original fictional dialogue, both in Spanish (Gómez Capuz 2001; Romero-Fresco 2009a) and in other languages (Pavesi 2008; Matamala 2009; Perego and Taylor 2009; Barambones 2012; Bonsignori, Bruti et al. 2012). Many authors have highlighted the artificiality of the language of dubbing, reporting unnatural or unidiomatic uses of specific features such as discourse markers and intensifiers (Romero-Fresco 2009a), vocatives (Dolç and Santamaria 1998), interjections (Cuenca 2006; Matamala 2009), substandard language (von Flotow 2009), or anglicisms (Herbst 1997; Gómez Capuz 2001; Duro 2001). These unidiomatic uses have often been analyzed from the point of view of pragmatic interference and, in the case of Spanish, have led to worrying and alarmist warnings about the creation of a language which according to Duro (2001: 163) sounds fake, uncomfortable, unnatural, contaminated and slightly annoying.

In the professional environment, recommendations made by dubbing studios and television production companies seem to suggest that translators should not imitate spontaneous conversation freely. According to Ávila (1997: 25-26), dubbing studios recommend using standard language to achieve clear and simple dialogues which meet the needs of viewers. Similarly, in its Criteris lingüístics sobre traducció i doblatge[2] (Linguistic Criteria for Translation and Dubbing), Televisió de Catalunya (1997: 11) suggests that some linguistic features of spoken Catalan should be exclusive to native programs and thus not be used in audiovisual texts dubbed into Catalan. Given these recommendations, the apparent distance between original and dubbed productions, and the wealth of criticisms and opinions to which dubbing language is subjected, exploring the divergences and similarities between native and dubbed productions is of particular relevance. And the relevance of such an analysis is even greater in the case of products broadcast on television, given its global influence and its ability to attract as many criticisms as viewers.

This article sets out to provide an overview of how Spanish fictional dialogue is shaped from a linguistic point of view across all language levels (phonetic, morphological, syntactic and lexical) in television series, highlighting the trends identified in their production and translation in order to compare them at a later stage. For this purpose, an audiovisual corpus comprised of domestic and dubbed sitcoms in Spanish (Siete Vidas and Friends respectively) will be analyzed from a quantitative and qualitative point of view, drawing on the features identified in the analytical framework designed for this purpose (see 4.1.). Before introducing the audiovisual corpus and delving into the methodological approach adopted, it is necessary to define briefly the concept of prefabricated orality and to reflect on the different factors governing the selection of linguistic material in domestic and dubbed productions. The main findings and conclusions will then be summarized, not only with regards to the comparison of Friends and Siete Vidas, but also regarding the comparison of pre and post-production scripts in the case of the domestic sitcom, and of the original and dubbed version in the case of the foreign sitcom.

2. Native and dubbed prefabricated orality: an overview

The concept of prefabricated orality lies in the very nature of the register of audiovisual texts, and it is determined by their specific mode of discourse, which is spoken yet planned or elaborated. Most audiovisual texts, especially those featuring fictional dialogue, originate in a script that has been carefully planned and written in order to be interpreted by actors as if it had not been written (Gregory and Carroll 1978: 42). Scriptwriters and actors will imitate certain features of spontaneous conversation to achieve credible, realistic and natural-sounding dialogues, yet they will do so non-spontaneously in most cases. The planned nature of fictional dialogue is such that it has even been defined as “straightjacketed dialogue that is intended to sound natural” (Romero-Fresco 2009a: 56). Drawing on Salvador (1989), Chaume (2004a: 168) states that the spontaneity of the linguistic code of most audiovisual texts is pretended, which is why their orality has been termed “prefabricated.”

Scriptwriting manuals promote the use of dynamic dialogues, which sound credible and could be identified by viewers as true-to-life conversation. However, divergences between spontaneous conversation and fictional dialogue are obvious if we consider the communicative situation and reflect on the multiple “filters” audiovisual texts have to go through:

In narrative films, dialogue may strive mightily to imitate natural conversation, but it is always an imitation. It has been scripted, written and rewritten, censored, polished, rehearsed, and performed. Even when lines are improvised on the set, they have been spoken by impersonators, judged, approved, and allowed to remain. […] The actual hesitations, repetitions, digressions, grunts, interruptions, and mutterings of everyday speech have either been pruned away, or, if not, deliberately included

Kozloff 2000: 18

Kozloff’s views are shared by most scholars, who agree that conversational exchanges taking place in audiovisual products are just part of the illusion created in cinema or television. However, very few scholarly works have been devoted to exploring how this illusion is achieved from a linguistic point of view. Quaglio (2009: 10) highlights how screenwriting manuals seem to “rely on native-speaker intuition,” and provide virtually no linguistic information. In fact, most monographs on screenwriting are either anecdotal or highly prescriptive (see Flinn 1999), and authors seem to take for granted that scriptwriters master spoken registers, and that they are skilful at selecting the right linguistic features to create spontaneous-sounding dialogues (see McKee 1998 or Field 2003). When providing tips to scriptwriters, Toledano and Verde (2007), refer to this issue briefly, arguing that good dialogue writing can be learned and improved. These authors suggest paying attention to “what people say in the street, on a bus, on the tube, and not only to how it is said, but also to what is being said” (Toledano and Verde 2007: 155; my translation), and emphasize the importance of carrying out a thorough documentation process in order to write credible dialogues. This documentation process would involve the identification and subsequent selection of orality markers or carriers, understood as features typifying spontaneous spoken register used in prefabricated dialogue to reinforce its orality and to convey a false sense of spontaneity.

Regarding the use of orality markers in fictional dialogue, the research carried out by Quaglio (2009) on television dialogue in the series Friends in English reveals interesting similarities to spontaneous spoken register. The author concludes that “Friends shares the core linguistic features that characterize natural conversation” and highlights the fact that the differences between these two types of discourse are due to the restrictions and/or influences of the televised medium (Quaglio 2009: 139). Romero-Fresco also refers to the latter, and argues that predictability and relevance – the fact that dialogue must be succinct and precise – are some of the features that account for its dissimilarity to spontaneous conversation (Romero-Fresco 2009b: 47). These specificities would not allow for an excessive use of features which are typical of spontaneous conversation, such as hesitations or vague language, for example, as they might contravene the relevance principle and distract viewers, who are already familiar with the specific register of audiovisual products. Taylor has referred to the specific language of film or to screen discourse as filmese, highlighting the tension established between “the (subconscious) conventions of film scripting and the priming mechanisms inherent to spontaneous talk adopted by actors” (Taylor 2004: 80). In a similar way, the term dubbese has been used in Translation Studies to refer to the specific register of dubbed texts, which according to Marzà and Chaume (2009: 36) could be defined as “a culture-specific linguistic and stylistic model for dubbed texts which has been named by some authors as a third norm, being similar, but not equal, to real oral discourse and external production oral discourse.” As this definition implies, prefabricated orality is also a characteristic of dubbed productions, which has an impact on how the language of dubbing is shaped.

In the case of dubbing, translators must bear in mind that the dialogues of the original audiovisual text, which would need to be translated taking into consideration the interaction of multiple signifying codes, have been carefully written to be spoken to convey a sense of (false) spontaneity. In order to convey a similar impression of spontaneity in the target text, the translator takes the role of the scriptwriter, and should thus master the linguistic features available in the target language to imitate spontaneous conversation – which might and probably will be different to those used in the source language. As in non-translated fictional productions, the credibility and verisimilitude of dialogues is one of the criteria used to ascertain whether a dubbed production meets quality standards (Chaume 2006: 8-9). However, in line with the recommendations made by Ávila (1997) and Televisió de Catalunya (1997) highlighted above, Chaume (2007: 215) considers that some features typifying spontaneous spoken conversation should be avoided by translators, who should bear in mind that “while the language of dubbing pretends to be spontaneous, it is very normative indeed.” In addition to the restrictions of the audiovisual media and the specificities of fictional dialogue, the mirroring of naturally-occurring conversation in dubbing will be influenced by further factors, such as the involvement of many agents and powers in the dubbing process, the target audience, professional issues, or the constraints imposed by the source text (ST) and the synchronization process required.[3] The filters dubbed products have to go through are more numerous than domestic products: once the audiovisual text has been translated it needs to be adapted and synchronized by the dialogue writer (Chaume 2004b: 43) before being interpreted by dubbing actors, under the supervision of the dubbing director and the linguistic supervisor (if applicable). As shown by Matamala (2010: 113) in the case of Spanish and Catalan, many changes are implemented not only during the synchronization and language revision stage, but also during the actual recording.

The reflections included so far suggest that, although both dubbed and non-translated texts feature prefabricated discourse, and although both scriptwriters and translators should aim to achieve a balance between speech and writing, non-translated and dubbed audiovisual texts are governed by different norms and factors, which will have an impact on the linguistic material chosen to achieve credible dialogues. Taking this as a starting hypothesis, the purpose of this article is to compare translated and non-translated sitcoms in order to find out what makes dubbed texts stand out from domestic productions. The following section will provide details on the selection of the audiovisual corpus. We will then explain the methodological approach adopted before presenting the main findings of the research.

3. The audiovisual corpus

The audiovisual corpus consists of a main comparable corpus in Spanish and a secondary corpus (both parallel and comparable). The main corpus is divided into two sub-corpora: native texts (sub-corpus 1) and dubbed texts (sub-corpus 2). The native sub-corpus comprises two episodes of the Spanish TV series Siete Vidas, as aired on Spanish television, and their respective post-production scripts, which have been compared with the final audiovisual product. According to the information provided by the television production company, the scripts of the Spanish sitcom were written by several scriptwriters, with approximately five people working on each script. The dubbed sub-corpus consists of five episodes of the US television series Friends in Spanish, and their respective scripts. These episodes have been translated by a single audiovisual translator, who was not responsible for the adaptation and synchronization of the dialogues. The duration of each episode is the main reason for the difference between the number of episodes included in each sub-corpus, as episodes of Friends normally last 25 minutes, whereas the duration of the Spanish sitcom is nearly double that (approximately 50 minutes). Both components were considered comparable as far as their duration was concerned (approximately 100 minutes of each TV series were compared).

Several criteria regarding the suitability and the similarities of the two TV series chosen were taken into consideration when designing this main corpus. It was decided to analyze sitcoms, since mirroring natural conversation is essential in series belonging to this genre. As the aim was to compile a homogeneous and comparable corpus, the purpose was to choose two audiovisual products that had a similar profile and bore significant resemblances to each other regarding genre conventions, theme, broadcasting characteristics and viewership. When choosing specific episodes, the availability of scripts and texts, as well as the field of discourse, was taken into consideration. The final decision was to analyze the following episodes, where the main plot is built around the pregnancy of Rachel (in Friends) and Carlota (in Siete Vidas):

Table 1

Episodes included in the corpus

The secondary corpus comprises texts that will be analyzed in specific cases, and can also be divided into two sub-corpora: Siete Vidas pre-production scripts (sub-corpus 3) and the original episodes of Friends (sub-corpus 4). When compared to the above-mentioned native sub-corpus, the former will provide us with a monolingual comparable or draft corpus, which will be used to shed light on the type of orality markers that are inserted by actors while interpreting the dialogues. Likewise, when compared to their dubbed counterparts, the original episodes of Friends will provide us with a bilingual parallel corpus (English-Spanish), which will shed light on the type of orality markers which might be motivated by the ST, and those used by translators to adapt the text to target language conventions.

As shown in Figure 1, the addition of this corpus enables us to establish comparisons at three different levels: between native and dubbed texts; between Siete Vidas’ pre and post-production scripts (sub-corpus 3 and 1 respectively); and between the original and the dubbed version of Friends (sub-corpus 4 and 2 respectively).

Figure 1

Corpus design

4. Methodology

This research can be defined as a corpus-based translation study[11] whose theoretical framework and methodological approach is based on Descriptive Translation Studies and Polysystem theory. Following Toury’s (1995: 58-59) approach, the study involves the investigation of operational norms, specifically of textual-linguistic norms. By observing dubbed and non-translated audiovisual texts, the aim is to describe the regularities that govern the selection of linguistic material to imitate spontaneous-sounding conversation. For this purpose, we consider that, in spite of being active in the same target system, norms governing this selection in sub-corpus 1 and sub-corpus 2 might differ. The notion of norm provides an appropriate framework to undertake the description of orality markers in our audiovisual corpus, whereas the concept of polysystem allows us to place such a description in a specific socio-cultural context distinguishing between a subsystem of non-translated audiovisual texts and a subsystem of translated (dubbed) audiovisual texts.

In order to undertake the description and identification of regularities in our corpus, an analytical framework was designed, as explained in 4.1. When applying this framework a target-oriented approach was adopted. The native sub-corpus and the dubbed sub-corpus episodes were analyzed independently, both from a quantitative and a qualitative point of view. While watching the episodes, orality markers were identified and all occurrences were classified and entered in an Excel spreadsheet in order to ease quantification. Filters were inserted in the spreadsheet to quantify orality markers and, in specific cases, the corpus analysis tool AntConc 3.2.1w was used (for example to quantify occurrences of personal deixis). Not all orality carriers were analyzed from a quantitative point of view as in some cases this was not feasible (for example the analysis of grammatical ellipsis). Data was then analyzed from a qualitative point of view: trends were inferred taking into consideration factors influencing the selection of orality markers in translated and non-translated texts, as well as the specific nature of audiovisual texts and audiovisual translation, paying special attention to dubbing constraints.

Pre and post-production scripts (sub-corpora 3 and 1 respectively) were contrasted in those cases where it was thought that such a comparison would shed light on relevant aspects such as the actors’ ability to improvise. Similarly, source and target texts (sub-corpora 2 and 4) were contrasted when it was considered that the comparison would contribute to the understanding of the presence of specific orality carriers in the target text, as well as to determine the influence of the ST in the selection of linguistic material. It is worth noting that this comparison is only partial and that it takes the target text, and not the source text, as a starting point for the analysis.

To conclude, the regularities identified when analyzing translated and non-translated dialogues were compared in order to draw conclusions and to identify similarities and divergences between Siete Vidas and Friends, both from a qualitative and from a quantitative point of view (where feasible), according to the levels of language and the orality markers identified in the analytical framework, the design of which will be explored below.

The following diagram summarizes the steps taken:

Figure 2

Methodology

4.1. An analytical framework for the analysis of orality markers in audiovisual texts

The design of the methodological framework involved identifying which specific linguistic features would be analyzed and contrasted in the audiovisual corpus. For this purpose, an analytical framework was designed, drawing on the model suggested by Chaume (2004a: 168-186) and further developed in Baños-Piñero and Chaume (2009). This framework takes colloquial conversation (spontaneous spoken mode, colloquial register) as a benchmark, since this is the type of discourse being mirrored in sitcoms. The framework refers to specific and general features whose analysis is relevant considering the object of study and the type of discourse being imitated. These features have been selected taking into consideration research carried out on spontaneous colloquial conversation (Weinstein 1982; Vigara 1992; Briz 1996 and 2001; Carter and McCarthy 1997; Biber, Johansson et al. 1999), on fictional dialogue (Comparato 1993; Kozloff 2000; Toledano and Verde 2007; Quaglio 2009), and on the characteristics of dubbese (Chaume 2004a; Pavesi 2008; Romero-Fresco 2009a). Although the framework draws on works in English and in Spanish, priority has been given to those characteristics which are typical of the Spanish language in the above-mentioned discourse types. Nevertheless, this model could be adapted accordingly for future studies and applied to other languages. The framework has been structured according to the traditional structuralist language levels: phonetic-prosodic, morphological, syntactic and lexical-semantic. The following tables summarize the analytical framework at each language level:

Table 2

Analytical framework: phonetic-prosodic level

Table 3

Analytical framework: morphological level

Table 4

Analytical framework: syntactic level

Table 5

Analytical framework: lexical-semantic level

5. Comparing orality markers in native and dubbed sitcoms: Siete Vidas and Friends

Findings suggest that the domestic sitcom bears more resemblance to spontaneous conversation than the dubbed sitcom at all language levels. Divergences are marked at the phonetic-prosodic and morphological levels, and less significant at the syntactic and lexical level, where scriptwriters and the translator follow similar conventions and use analogous linguistic resources to mirror spontaneous conversation. From a syntactic and lexical point of view, divergences often lie in the frequency and variety of orality markers, which tend to be higher in Siete Vidas. There are, however, some exceptions at the lexical level, showing that certain orality carriers are more frequent in Friends. This reveals that the translator prioritizes the use of specific features or, as Pavesi (2009: 98) puts it, uses “privileged carriers of orality”[12] at the lexical level, which seems to be overloaded in the case of Friends if compared to other levels.

The following sub-sections summarize and exemplify the main findings at each language level. Due to space constraints, the focus will be on the main regularities identified, especially with regards to significant differences between domestic and dubbed productions.

5.1. Phonetic-prosodic level

Siete Vidas and Friends show significant dissimilarities at the phonetic level and some similarities at the prosodic level. Regarding the latter, both original and dubbing actors use clear pronunciation, where emphasis and intonation contribute to the organization of prefabricated speech, and facilitate the viewer’s understanding of on-screen conversation. Elongation of sounds and incidences of emphatic pronunciation add expressivity and intensify what has been said both in the domestic and the dubbed sitcom, as shown in (1) and (2) below. In the case of dubbing, it is worth noting that the inclusion of these markers helps to comply with dubbing synchronies. However, in some cases, these might account for the inclusion of features which are not idiomatic in the target language, as shown in (2b), where syllabic division does not comply with pronunciation conventions in Spanish.

There are major divergences between Siete Vidas and Friends with regards to phonetic articulation, which, overall, is relaxed in the domestic sitcom and extremely tense in the dubbed sitcom. The analysis has shown that phonetic relaxation is an intermittent phenomenon in Siete Vidas which contributes to bringing fictional dialogue closer to spontaneous conversation. In the discourse being mirrored (spontaneous conversation), phonetic relaxation is a result of the implementation of efficiency and economy principles, as the speaker will “make articulatory gestures that are sufficient to allow the units of his message to be identified but he will reduce any articulatory gesture whose explicit movement is not necessary to the comprehension of his message” (Brown 1977: 57). According to Briz (1996: 49), the elision and addition of sounds, as well as the assimilation and aspiration of sounds are frequent features in colloquial conversation in Spanish. Some of these features are also present in Siete Vidas, as shown in the table below, but completely absent in Friends.

Table 6

Phonetic articulation in Siete Vidas

In the case of Friends, no quantitative data can be provided, as no occurrences of relaxed articulation have been found in the dubbed sub-corpus. This proves that, as argued by Chaume (2004a: 171), Spanish dubbed productions are characterized by tense phonetic articulation. This seems to be a specific dubbing feature, since occurrences of relaxed phonetic articulation are frequent in the original version of Friends, where the following can be found: assimilations (gonna > going to; wanna > want to; gotta > got to), weakening (ta > to, ya > you, yer > your, sayin’ > saying), elision of sounds (’n’ > and, ’em > them, ’cause > because, ’til > until), and combinations of these features (y’know > you know, how daya > how do you). Relaxed phonetic articulation is not the only feature that becomes standardized in dubbing at this level. Standardization also affects regional and social accents, which are marked in the domestic sitcom (in Siete Vidas the southern accent of Frutero is fully exploited for his characterization) but neutralized in Friends, where dubbing actors use a standard Spanish accent. Regional and social accents are only maintained or transferred when they are essential to understand the plot or to convey humor. This is the case with the following example, where a Mexican accent is used by the Spanish dubbing actor to render the original utterance in which Joey tries to use a Jamaican accent. The humorous effect is achieved through the use of markers both at the phonetic and lexical level (as the vocative compadre is commonly used in some Spanish speaking countries in Latin America and also in some parts of southern Spain).

5.2. Morphological level

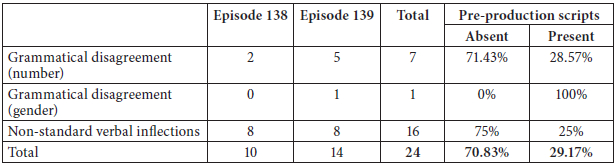

Results point to the fact that orality markers at this level are more recurrent in the Spanish sitcom, which therefore bears more resemblance to spontaneous conversation than the dubbed production. Standardization seems to account for these differences, since it characterizes the discourse of the dubbed sitcom. This contrasts with the occasional use of non-standard and seemingly spontaneous morphological features in the domestic production, such as grammatical inconsistencies (gender and number) and non-standard verbal inflections, as shown in the table below:

Table 7

Non-standard features at the morphological level in Siete Vidas

Biber, Johansson et al. (1999: 1064) refer to these phenomena as syntactic blends or anacolutha, which are frequent in colloquial conversation and seem to be a result of the speaker suffering from “a kind of syntactic memory loss in the course of production.” In this case, it is presumably the actors suffering from this memory loss when interpreting the lines, especially if we take into consideration the fact that the majority of these inconsistencies were not present in the pre-production scripts (70.83%), thus suggesting that they were introduced by the actors while filming. The following utterances exemplify grammatically incorrect or non-standard features which, although “deemed bad style and poorly thought out in a written text, are exactly what make a spoken dialogue animated, credible, authentic and human” (Whitman-Linsen 1992: 32).

The first example illustrates a case of number inconsistency, as Diana uses the singular drag queen instead of the plural, which is grammatically incorrect as it does not agree with the article las. According to Vigara (1992: 193), the second example illustrates a very common error in colloquial conversation in Spanish, motivated by the phonic analogy of the past tense tenía que besar [she had to/must kiss], and the conditional tense tendría [she should kiss], which is grammatically correct. According to Briz (1996: 59) by choosing the past tense, which in this case implies obligation, the involvement of the speaker in the conversation increases, which – in my view – results in a more emphatic and marked colloquial dialogue.

These orality markers help to achieve convincing and authentic dialogues and, despite being common in written media (Aleza 2006: 49), should be avoided according to normative grammar. This could be one of the reasons why these non-standard features are absent in the prefabricated discourse of the dubbed sitcom, which is grammatically correct and standard at the morphological level. As grammatical inconsistencies are present in the source text (in He kinda takes your breath away don’t he? and in We don’t need no stinkin’ badges!), this again seems to be a characteristic of dubbese.

5.3. Syntactic level

Resemblances between the domestic and the foreign production are greater at the syntactic level than at the above-mentioned levels. However, the analysis has revealed again that the discourse of the domestic sitcom seems less prefabricated than that of the dubbed series. The main divergences lie in the frequency and variety of orality markers, which, overall, are more diverse and recurrent in the domestic series.

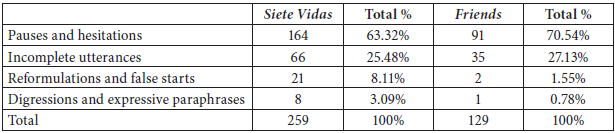

5.3.1. Textual organization

Both the translator of Friends and the scriptwriters of Siete Vidas tend to use short and simple syntactic structures which seem to prevail in fictional dialogue (Kozloff 2000: 29), and in spontaneous conversation (Brown and Yule 1983: 16-17). This contributes to the achievement of dynamic, precise and witty dialogues, which according to Comparato (1993: 249) are the staple of sitcoms. Although the discourse is fluent overall in both sitcoms, it is in some cases disrupted by the use of syntactic dysfluencies which are frequent in natural conversation, such as pauses and hesitations, reformulations and incomplete utterances. The incidence of these phenomena cannot be compared by any means to spontaneous speech, where minor dysfluencies are very common (Biber, Johansson et al. 1999: 1053). The prevalent use of these features might not compromise understanding in naturally-occurring conversation, but it would in fictional dialogue, where precision is a must. The presence of these features in domestic and dubbed productions reflects an attempt to mirror spontaneous-sounding conversation, but their controlled use reveals the intention to avoid an overuse which could interfere with the viewers’ understanding of what is happening on screen. The following table summarizes quantitative findings regarding the use of dysfluencies in domestic and foreign sitcoms, and shows that these orality markers are more frequent in Siete Vidas than in Friends.

Table 8

Syntactic dysfluencies in Siete Vidas and in Friends

The following examples illustrate the use of several forms of dysfluency both in Siete Vidas (example 6) and in Friends (example 7) and reveal the similarities in the features used, especially with regards to filled pauses (eh in both examples), which are defined by Biber, Johansson et al. (1999: 1053) as pauses that are “occupied not by silence, but by a vowel sound, with or without accompanying nasalization.”

In example 7 above, it is worth noting that the omission of the hesitations and repetitions in the dubbed version would not only diminish the authenticity of the dialogues, but it would also result in the failure to comply with isochrony. In other instances, translators or dialogue writers might need to implement reduction strategies to comply with this type of synchrony, in which case the latter might be responsible for the omission of dysfluencies in the target text. This phenomenon is shown in the following example, where some hesitations are maintained in the dubbed version (Um > Eh), others are omitted (Isn’t that, isn’t that, Y’know um) or explicitly verbalized with utterances expressing hesitation (I mean, we-we’re has been translated as no sé > I do not know). These omissions inevitably result in a loss of pretended spontaneity.

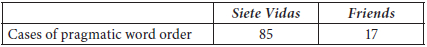

When analyzing the order of clause elements in Spanish prefabricated discourse, it is essential to take into consideration the fact that word order in Spanish is more flexible than in other languages such as English or French (Padilla 2000: 230), and that the organization of clause elements following pragmatic (or non-canonical) patterns is typical of Spanish conversation. Both in Siete Vidas and in Friends, word order tends to be canonical, following the structure subject+verb+object. However, in some cases, scriptwriters and translators emphasize specific elements through topicalization or fronting, and through inversion.[13] According to the quantitative analysis,[14] these phenomena are more common in the domestic sitcom than in the dubbed sitcom, as shown in the table below.

Table 9

Word order in Siete Vidas and in Friends

Divergences between Siete Vidas and Friends do not only lie in frequency. The variety of the cases analyzed is also greater in the domestic sitcom, where scriptwriters use structures which are common in Spanish colloquial conversation, such as inversions, dislocations to the left of the sentence (see Padilla 2000: 230), or structures where the demonstrative pronoun este/ese is postponed in noun phrases, such as lleva toda la semana quedando con el tío este, which could be translated literally as she’s been all week meeting the guy this.

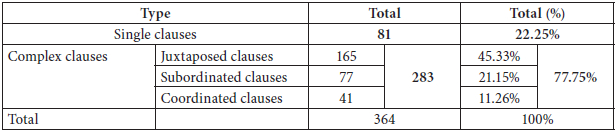

5.3.2. Link between clauses and phrases

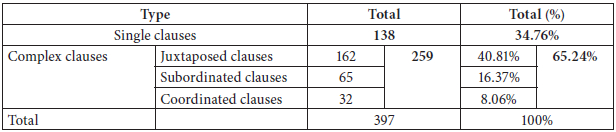

In order to study how clauses are linked in prefabricated discourse, the first ten minutes of episode 138 were analyzed in the case of Siete Vidas, and of episode 190 in Friends. In each case, the number of clauses was quantified, and then classified into simple and complex clauses. The latter were also classified into juxtaposed, coordinated and subordinated clauses. The results, which have been summarized in the tables below, reveal some similarities between the two sitcoms: complex clauses are more common than simple clauses in fictional dialogue, and these are primarily juxtaposed.

Table 10

Syntactic structures: types of clauses in Siete Vidas

Table 11

Syntactic structures: types of clauses in Friends

According to Vigara (1992), the results reveal similarities between prefabricated and spontaneous discourse as, in the latter, juxtaposition prevails over coordination and subordination. However, they also reveal interesting differences, as in natural conversation coordinated clauses seem to be more common than subordinated clauses (Vigara 1992: 115), and this trend is not shown in the corpus under study. The prevalence of subordination over coordination in the corpus could be a result of the high level of prefabrication of fictional discourse, where the lack of spontaneity might allow for the inclusion of stronger links between clauses.

In addition to conjunctions frequently used in colloquial conversation, cohesive devices such as discourse markers, stereotypical structures of conversation, interjections, and vocatives, are common in both series. The prevalent use of these features brings prefabricated discourse closer to spontaneous conversation. It is worth noting, however, that the frequency and variety of these orality markers seems higher in the case of Siete Vidas, and that some of the markers identified in the dubbed sub-corpus are not idiomatic in the target language. This is the case with the vocatives consisting of the form of address and the surname of the person being addressed (such as Sra. Green, Dra. Long or Señores Geller), which might be common in English spontaneous conversation (Biber, Johansson et al. 1999: 1109-1111), but they are not in colloquial spoken Spanish. The same applies to the interjections ¡ups! and ¡yuju!, used to translate ¡whoops! and ¡yoo-hoo!.

5.3.3. Exophoric reference

Spontaneous conversation and fictional dialogue rely heavily on contextual information, which is linguistically expressed through an abundant use of deictics referring to the situation (place and time) in which the conversation takes place. The analysis has shown that these orality markers are common in both Friends and Siete Vidas. However, the most interesting results stem from the analysis of personal deictics, especially of the use of 1st and 2nd person singular personal pronouns (yo > I and tú > you) which, according to Briz (1996: 56), are prevalent features in spontaneous colloquial conversation, and are indicative of its egocentric nature. Quantitative results reveal that these personal deictics are more pervasive in native sitcoms than in dubbed sitcoms.

Table 12

Personal deictics (1st and 2nd person singular personal pronouns) in Siete Vidas and Friends

It is essential to note that in Spanish, unlike English, grammatical subjects are not compulsory as they are marked morphologically. The pronouns yo and tú in Spanish colloquial conversation are thus included with a specific pragmatic intention, often with the purpose of intensifying or downtoning the role of speakers in conversation (Briz 1996: 56). The two examples given below exemplify the use of these deictics which could have been omitted from a grammatical point of view, but reinforce the pivotal role of speakers in conversation, and act as orality carriers that contribute to the authenticity of dialogues. In the case of Friends, the use of these markers might even help to achieve synchrony, as shown in (10) below, where the use of the first person pronoun contributes to matching the target text to the lip movements and duration of Phoebe’s utterance.

The quantitative analysis also shows that the frequency of the second person formal pronoun usted is higher in Friends than in Siete Vidas. This phenomenon should be further explored to extract relevant conclusions, but this might be related to the use of a single pronoun in English to address the interlocutor formally and informally (you): in order to highlight the fact that the level of formality in conversation is higher at a given point, the translator might have decided to include the explicit subject (usted), even if this was already marked morphologically.

5.3.4. Use of redundancy and ellipsis

Colloquial conversation, both in English and in Spanish, is characterized by being highly redundant. Redundancy is often expressed linguistically in both Siete Vidas and Friends by means of repetition of words, phrases and even clauses. In other cases, the speaker might consider it relevant to avoid unnecessary repetition by using elliptic structures, which are also common in the corpus. The qualitative analysis shows that both the translator of Friends and the scriptwriters of Siete Vidas try to elide clause elements when possible in order to avoid unnecessary repetition. In the case of dubbing, ellipsis is also a useful feature to reduce target language utterances and comply with isochrony, as shown in example 11 below, where the translator has elided the verb (Y usted (será) una abuela maravillosa), as the information is implicit and can be retrieved by the viewer without difficulty.

Regarding the use of these markers in Siete Vidas, it is worth referring to the elision of prepositions, a phenomenon which is common in colloquial conversation (Vigara 1992: 206), but censured in writing, and avoided in the dubbed sitcom. The following example shows one of the 12 occurrences of elision of prepositions identified in the domestic sub-corpus (note that the preposition which has been elided has been enclosed in brackets).

Although grammatically incorrect, this feature is common in Spanish spontaneous speech, and contributes to the text being identified as spontaneous-sounding conversation by viewers. Following Vigara, this shift could be considered an example of the implementation of the convenience principle, defined by the author as the speaker’s “spontaneous tendency to achieve communication with minimum effort” (Vigara 1992: 187; my translation).

5.4. Lexical-semantic level

At this level Siete Vidas and Friends present strong similarities, since scriptwriters and the translator follow similar conventions and use comparable linguistic resources to mirror spontaneous conversation.

5.4.1. Lexical choice

The analysis has revealed that “vague language” (Quaglio 2009: 72) is one of the markers of orality used by scriptwriters and translators to mirror natural conversation. Both in Siete Vidas and in Friends, nouns and pronouns of vague reference such as cosas [things] or esto/eso [this/that], or “delexical verbs” (Cornbleet and Carter 2001: 63) such as tener [have] or hacer [do], are used to convey the vagueness that characterizes spontaneous conversation. Although this seems to be the general trend in both cases, we have identified a number of cases of terminological precision in dubbing, which are worth mentioning. In some cases, it seems the translator prioritizes the use of appropriate collocations and expressions to the detriment of vague expressions, as shown in the following example.

In the example above, the translator has used the collocation saldar las cuentas [to pay off] to translate settle things, instead of a more generic and imprecise option (for instance, arreglar las cosas), and has specified money (cuánto dinero te debo > how much money do I owe you) even though ¿cuánto te debo? would be correct and probably more likely to appear in conversation. While it could be argued that in the second part of this example, lexical selection might be motivated by synchrony restrictions (isochrony), this cannot be used as an argument for the first part of the example, as arreglar las cosas could be adapted perfectly well to the duration of on-screen characters’ utterances. This example emphasizes the essential role played by translators and dialogue writers and the impact of lexical selection on dubbed dialogues, which in some cases simulate spoken speech but in others seem to comply with existing conventions applicable to written texts, where precision is favored to the detriment of vagueness (Sanmartín 2006: 245).

In addition to vague language, colloquial lexis is also a feature of both Siete Vidas and Friends. Lexical choices made by scriptwriters in the domestic sitcom are often marked, in the sense that they are more common in colloquial conversation: montón [loads] instead of mucho, horrible instead of mal [bad], picarse [get cross] instead of enfadarse [get angry], or chiflar [to be mad about something] instead of gustar [like]. We can find similar examples in the Spanish version of Friends, where characters say criatura [creature] instead of bebé [baby], chungo [dodgy] instead of malo [bad], or pillar [get] instead of entender [understand].

5.4.2. Lexical creation

With regards to lexical creation, argotic terms – and especially youth lingo which has already become part of colloquial language – are frequently used in Siete Vidas and in Friends, probably to connect with the series’ target audience. The Spanish sitcom differs from the foreign one in that scriptwriters also use terms belonging to criminal argot (for instance, talego and trullo to refer to jail), and to professional lingo (for instance, terms related to bullfighting). Since the texts being analyzed belong to the genre of situation comedy, specialized terms are practically absent in the corpus. Considering their rarity in colloquial language, the use of these terms in fictional dialogue often has a comic purpose.

Although not frequent, loan words have been identified in both sub-corpora (19 cases in Siete Vidas and only 14 in Friends). It has been noted that most of the loan words analyzed have become widespread in Spanish, and are even sanctioned by the Spanish Royal Academy, thus fully belonging to the Spanish language (for instance whisky, puzzle, drag queen or pizza in Siete Vidas; gay, póster, chef or striptease in Friends). As for the origins of the loan words, those used in Friends are either anglicisms or gallicisms. In Siete Vidas, however, scriptwriters borrow words from various languages such as Chinese (Tai-Chi), Korean (taekwondo), Japanese (karaoke) or English (burguer, used instead of hamburguesería > burger bar).

Interesting trends have been identified regarding lexical creation through morphological processes. Among these processes, Briz (1996: 53) emphasizes the high incidence of suffixes and prefixes in Spanish colloquial conversation – which often act as intensifiers –, whereas Vigara (1992: 212) explores the role of shortening processes in relation to the above-mentioned convenience principle. The following table summarizes the quantitative results of these features in the corpus.

Table 13

Lexical creation through morphological processes in Siete Vidas and Friends

As can be seen in the table above, suffixation is the most common process, followed by shortening processes and prefixation. Suffixation is however much more frequent in the domestic sitcom (80.26% against 47.37%) and divergences are especially marked in the case of diminutive suffixes (such as -ito/-ita), which are more frequent and varied in Siete Vidas. The following excerpt from Siete Vidas illustrates several examples of diminutive suffixes (boquita, barbillita, poquito, pobrecita), used mainly as diminishers or downtoners, and of a superlative suffix (-ísima) used as an intensifier.

Looking at the table, an interesting and unusual trend can be identified when comparing the quantitative data drawn from the analysis: some morphological processes are more pervasive in the dubbed sitcom. This is the case with superlative suffixes (ísimo/ísima) and prefixes (mainly súper-) – which are used as intensifiers in prefabricated discourse –, and of shortening processes, which are not only more frequent but also more varied in the Spanish version of Friends, where televisión becomes tele, película [film] becomes peli, colegio [school] becomes cole, and divertido [fun] becomes diver, for instance. The following examples illustrate how these features are used in the dubbed episodes of the US sitcom.

Whereas in (15b) and (15d) it could be argued that the intensifier really in the original version has been translated by means of a superlative suffix (in monísima) and the prefix super- (in superviolenta), in examples (15a) and (15c) the use of the orality markers being explored is not directly motivated by the original text. In order to understand the high prevalence of specific morphological processes for lexical creation, one must take into consideration the facts that: a) these features might have been used to translate adverbial intensifiers (such as really or so), which are extremely frequent in Friends as reported by Tagliamonte and Roberts (2005) and Quaglio (2009); b) the translator might overuse features at the lexical-semantic level in an attempt to compensate for the omission of features at other levels (for example phonetic-prosodic and morphologic). In any case, the analysis reveals that the dubbed sitcom complies with target language norms by using orality carriers which are typical of colloquial conversation in Spanish, which often do not have a direct equivalent in the source language (for example shortening processes or diminutives).

5.4.3. Expressivity and creativity

Linguistic features associated with creativity and expressivity such as phraseological units, colloquial expressions, metaphors and other figures of speech are abundant in Siete Vidas and Friends. When exploring this phenomenon, the focus will be on the use of phraseological units, following the classification offered by Corpas (1997), as they are frequent in colloquial conversation. The comparative analysis of these orality markers has revealed very interesting findings. Firstly, the analysis has shown that from a quantitative point of view, the domestic and the dubbed sitcom bear similarities regarding the use of phraseological units, as shown in the table below:

Table 14

Phraseology in Siete Vidas and Friends[15]

Quantitative similarities are significant, especially if we take into consideration the fact that most of the orality markers analyzed so far seem to be much more prevalent in the domestic sitcom. However, in line with previous results, native dialogues are yet again more original and “domesticating,” whereas dubbed dialogues are more stereotyped and conventional. This conclusion is drawn based on the following findings.

Firstly, although routine formulas are more varied in Siete Vidas, they are more prevalent in Friends (147 occurrences against only 99 in the domestic sitcom). Conversational routines abound in Friends, and some phraseological units occur more than ten times in the dubbed sub-corpus (for instance, ¡Dios mío! > Oh my God! and Lo siento > I’m sorry). These results reveal the stereotypical and formulaic nature of dubbese, and coincide with the findings of authors such as Chaume (2004a: 179) or Pavesi (2008: 94).

Secondly, idiomatic expressions and proverbs are more frequent and varied in the domestic sitcom than in the foreign sitcom. Actors in Siete Vidas use idioms and proverbs that are deeply rooted in the Spanish culture (such as ni lo sé, ni me importa > I don’t know and I don’t care), as well as extremely original sayings (los cementerios están llenos de valientes > cemeteries are full of brave people). On the contrary, some of the renderings used as proverbs in the dubbed version are not widespread in Spanish (for instance, the expression no existe la mala prensa, as a translation of there’s no such thing as bad press) and thus do not achieve the same pragmatic effect as the original fixed expression.

The qualitative analysis suggests that the use of phraseological units does not seem to be always motivated by the source text, as shown in the following examples, which might explain the high incidence of phraseological units in the dubbed sub-corpus.

In example 16 above, the agents taking part in the dubbing process have used the flexibility of the audiovisual medium to their own advantage adding two utterances featuring routine formulas that were not present in the original version: ¡No me digas! and ¡Qué va!. This insertion was possible because several characters were taking part in the conversation, and not all of them appeared on-screen when lines were uttered.

Examples 17a and 17b show that in some cases the translator includes phraseological units in the target text regardless of their presence in the original version when translating I’m totally crazy as estoy como una cabra [I’m as crazy as a goat] or hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life as casi me meo de la risa [I nearly wet my pants]. These findings coincide with the conclusions drawn by Romero-Fresco (2006: 143) in his study of phraseological units in the TV series Friends. This author reported a higher frequency of phraseological units in the dubbed version ascompared to the original version, and argued that the translator tended to include phraseological units that were not present in the original dialogues. At times, it seems that the translator is trying to compensate for the loss of orality and colloquiality markers at the phonetic and morphosyntactic levels by overusing lexical features that are typical of colloquial conversation, especially phraseological units (and lexical creation processes, as shown in 5.4.2.).

5.4.4. Swear words and lexical standardization

There appear to be considerable divergences between the domestic sitcom and the dubbed sitcom with regards to the use of swear words, offensive terms and barbarisms,[16] since they are much more frequent in Siete Vidas than in Friends, as shown in the table below.

Table 15

Swear words and barbarisms in Siete Vidas and Friends

Some differences are also observed regarding the type and purpose of swear words: Friends characters tend to use more offensive terms or insults addressed at other characters (for instance fulana or zorra, used to translate whore and bitch respectively), which are motivated by the situation in which the dialogue takes place and have a comic purpose. In Siete Vidas swear words are used with an expressive purpose, and are often added by actors to support their interpretation (for instance, ¡joder!, ¡coño! or ¡hostias!).[17] These kinds of expressions seem to be toned down in the foreign sitcom, where we can find euphemisms such as ¡jolines! (used to translate holy cow! or man!), ¡caray! (to translate wow! or man!) and puñetas (to translate how the hell). In addition, swear words and offensive terms are extremely varied in the domestic sitcom, where scriptwriters use terms that are deeply rooted in Spanish culture, such as gorrona or mamarracho, showing a higher degree of creativity.

Barbarisms are absent in Friends, but two occurrences have been found in the domestic corpus. These have been used in Siete Vidas with a humorous purpose, thus complying with sitcom genre conventions, which recommend the insertion of jokes every 10 to 15 seconds (Comparato 1993: 249). In general terms, results show that, overall, non-standard lexis is more pervasive in the native sub-corpus. Following conventions which are mainly designed with written communication in mind, the translator tends to use standard language. However, scriptwriters seem to disregard these conventions at times thus favoring a more authentic, colloquial and domesticating lexis.

6. Comparing pre and post-production scripts

The comparison between the pre and post-production scripts of the domestic sitcom has revealed that actors introduce a wealth of orality markers when oralizing the written script. At the phonetic level, for instance, actors sometimes disregard the orality carriers deliberately used by scriptwriters and they frequently load their utterances with other features typifying colloquial conversation through an intermittent relaxed phonetic articulation. Similarly, many of the morphological features used to mirror spontaneous conversation have been introduced during the shooting of the episodes, as these were not included in pre-production scripts. Actors also implement changes at the syntactic level, using features that help them to pretend they are not acting: syntactic dysfluencies (mainly pauses, hesitations and reformulations which are used as a support to remember their lines), personal deictics, discourse markers, interjections and vocatives, which are used to make their utterances sound more credible. According to the analysis carried out, lexical features are mainly introduced by scriptwriters and the role of actors regarding these is not as marked as in the previous language levels. Nevertheless, actors often pepper their utterances with suffixes and swear words, which are used to reinforce the expressivity of the final product.

These results show that actors’ improvisation plays an essential role in the patterning of prefabricated orality at the phonetic, morphological and syntactic level. This sort of controlled improvisation results in a more spontaneous and natural-sounding dialogue and could explain some of the differences identified in the contrastive analysis, as dubbing actors have less leeway to improvise (Matamala 2008: 93). In most cases, dubbing actors’ utterances are recorded separately under the supervision of the dubbing director. The absence of the rest of the “participants” in the conversation in the dubbing booth, together with the synchronization process required, might hinder the introduction of conversational features while recording the Spanish dubbed track. Also, the full weight of dubbing history in Spain, through which standard language has always been favored both on television and cinema screens, constitutes another factor that prevents the introduction of real conversational (especially colloquial) features in the translation.

7. Comparing the original and dubbed versions of Friends

The influence of the ST has become clear when comparing the original and dubbed versions of Friends: the inclusion of certain orality markers is directly motivated by the ST and on occasion this influence results in the introduction of features that are not natural or idiomatic in the target language. This is the case with some emphatic pronunciations, vocatives (such as Sra. Green, Dra. Long or Señores Geller), interjections (¡ups! and ¡yuju!), proverbs (No existe mala prensa) and personal deictics (the use of usted). Another trend identified in the analysis concerns the omission of some of the features which are typical of colloquial conversation and recurrent in the domestic sitcom as well as in the original version of Friends. Dubbing synchronies are not the only culprits for these omissions, as in some cases (often the most representative cases), omissions comply with norms favoring linguistic standardization. This can be noticed in the tense phonetic articulation of dubbing actors, in the absence of inconsistencies at the grammatical level and in the use of a standard lexis in the target text.

Some of the decisions taken by the translator could be associated with explicitation or simplification trends, such as when lexical precision is favored over vague language, or when hesitations and pauses are explicitly verbalized in the dubbed version, therefore giving priority to clarity. In other cases, however, the translator gives priority to target language conventions and uses orality markers which are not directly motivated by the source text. Baker (1996: 183) refers to this trend as “normalisation” or “conservatism” and in our sub-corpus it reveals an attempt to mirror spontaneous conversation by using typical features of spoken discourse. This trend becomes clear in the use of marked word orders, lexical creation through morphological processes, colloquial phraseology and argotic terms, among others. These are some of the trends identified in the partial comparison which, taking into consideration the limitations of our study, should be explored and tested in further works.

8. Conclusions

This article has provided an overview of how Spanish fictional dialogue is shaped from a linguistic point of view across all language levels, highlighting the main trends identified in its production and its translation. Findings have revealed that the use of orality markers with the purpose of recreating colloquial spontaneous conversation is higher at some language levels: the intersection between natural conversation and prefabricated discourse (both dubbed and native) reaches its peak at the lexical-semantic level, is remarkable at the syntactic level, less significant at the phonetic-prosodic, and minor at the morphological level. Focusing on prefabricated orality, an aspect that is specific to audiovisual texts and therefore to audiovisual translation, non-translated and dubbed sitcoms have been compared in order to find out what makes dubbed texts stand out from domestic productions. Divergences between domestic and dubbed productions often lie in the incidence and variety of orality markers, as these tend to be less frequent but more stereotyped and conventional in dubbing. The actors’ ability to improvise on the set and the greater leniency regarding sub-standard language exercised in domestic productions could account for differences in frequency, as they favor a more spontaneous and natural-sounding dialogue.

In both domestic and dubbed productions, the nature of fictional dialogue, its conventions and the restrictions of the televised medium determine linguistic selection and therefore have an impact on the patterning of prefabricated orality. In the case of dubbing, further factors apply, as dialogues are not only “constrained” by the ST and the synchronization process required, but also by the need to comply with specific conventions determined not only by the target language system, but also by the agents involved in the dubbing process and the alleged consolidation of a specific register for dubbing. As suggested by other scholars, the analysis has revealed that source text interference results in the introduction of unidiomatic or unnatural orality markers (or features that are more common in written and formal registers), and that some features are lost or neutralized in translation due to linguistic standardization and/or synchrony-related constraints. However, our research has also revealed promising and optimistic findings, showing similarities between the strategies used by scriptwriters and translators to achieve credible dialogues, as well as the inclusion of orality markers in Friends which were not present in the ST, and which are typical of colloquial conversation in Spanish. By using abundant phraseological units, prefixes and shortening processes which are typical of colloquial conversation in Spanish, the translator of Friends tries to bring dialogues closer to spontaneous speech, thus complying with target language norms, attempting to strike a balance between speech and writing, and compensating for the loss of other features.

Regarding the practical application of the conclusions drawn, we agree with Matamala (2009: 498) in that, due to the specific constraints of dubbing and the peculiarities of the communicative situation in which dubbed dialogues take place, we might never be able to put the language of dubbed sitcoms at the same level as that of domestic sitcoms. Nevertheless, we believe that the analysis of domestic productions can improve future audiovisual translators’ understanding of the specific features of fictional dialogue in the target language in specific genres, as well as of the strategies that could be resorted to in order to achieve credible, domesticating and natural-sounding dialogues. Integrating such an analysis in the curriculum of current audiovisual translation programs seems essential, especially when exploring a mode of audiovisual translation where conveying an impression of reality is necessary. To achieve this, translators-to-be should understand that existing dubbing conventions might not approve of using sub-standard features present in native productions (such as relaxed phonetic articulation, grammatical inconsistencies, or omission of prepositions) but that there are plenty of orality markers used in domestic productions which could be employed to achieve more domesticating and credible dialogues especially at the morphosyntactic level (pragmatic word order, personal deixis, ellipsis, syntactic dysfluencies, interjections, vocatives, etc.). This will increase critical awareness of the language of dubbing, its influencing factors, and the conventions that shape it.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

This article is drawn from a Ph.D. thesis completed by the author at the Universidad de Granada (Spain). Thanks are due to Charlotte Bosseaux for the translation of the abstract, and to Anna Milsom for her helpful comments and proof-reading.

-

[2]

An up-to-date version of these linguistic criteria can be found online at <http://esadir.cat/traduccio/lallengua>.

-

[3]

Chaume (2004b: 43-45) suggests three different types of synchronization in dubbing: phonetic or lip synchrony (which involves adapting the target text to the articulatory movements of the characters), kinesic synchrony (by which the translation should be synchronized with the actors’ body movements) and isochrony (referring to the synchronization of the translation with the duration of on-screen characters’ utterances).

-

[4]

Siete Vidas (2005): Episode 138. Resident Evil. Directed by R. A. Solla. SAV.

-

[5]

Siete Vidas (2005): Episode 139. Siempre nos quedará parir. Directed by M. Montero. SAV.

-

[6]

Friends (2003): Episode 190. The One with the Baby Shower. Directed by G. Halvorson. Warner Home Video.

-

[7]

Friends (2003): Episode 191. The One with the Cooking Class. Directed by G. Halvorson. Warner Home Video.

-

[8]

Friends (2003): Episode 192. The One where Rachel is Late. Directed by G. Halvorson. Warner Home Video.

-

[9]

Friends (2003): Episode 193. The One where Rachel has a Baby – part 1. Directed by K. S. Bright. Warner Home Video.

-

[10]

Friends (2003): Episode 194. The One where Rachel has a Baby – part 2. Directed by K. S. Bright. Warner Home Video.

-

[11]

The reasons for defining this research as a corpus-based translation study rather than as a case study lie in the methodological approach adopted. Despite the limitations of the study, especially with regards to the size of the audiovisual corpus, it is considered that this study falls under the umbrella of corpus-based studies since a corpus-driven methodology is applied to explore the nature of translated and non-translated audiovisual texts.

-

[12]

Pavesi (2009: 98) refers to the use of “privileged carriers of orality” in dubbing as “those structures which in the language of dubbing are mainly responsible for the impression of authenticity, or closeness of translated film dialogue to spontaneous spoken language.”

-

[13]

Biber, Johansson et al. (1999: 900) define fronting as a process which involves “the initial placement of core elements which are normally found in post-verbal position.” This phenomenon, which is relatively rare in English (Biber, Johansson et al. 1999: 1073), is common in Spanish colloquial conversation, and it is often referred to as topicalization (Padilla 2000: 232). In the case of inversion, the verb phrase precedes the subject (Biber, Johansson et al. 1999: 911).

-

[14]

The quantitative analysis only takes into consideration cases of word order where the conventional structure subject + verb + object has been altered following a pragmatic order (more logical for the speaker). Thus, alterations of complement phrases have not been taken into consideration, as their position in Spanish is very flexible.

-

[15]

Due to space constraints, only three of the four categories suggested by Corpas (1997) have been analyzed, thus leaving out the collocations category: idiomatic lexical bundles [locuciones], routine formulas [fórmulas rutinarias] and proverbs [paremias].The selection has been made taking into consideration that these phraseological units are typical and prevalent in colloquial conversation (Ruiz Gurillo 2000: 175), and they play an essential role in achieving lexical creativity and expressivity (Vigara 1992: 174). When analyzing what Corpas (1997: 270) terms “locuciones” [idioms or fixed expressions], we have focused on lexical bundles, leaving aside prepositional, adverbial or connective bundles for the above-mentioned reasons.

-

[16]

A barbarism is understood here as an improper or incorrect use of words at the lexical-semantic level. In Siete Vidas, for instance, one of the characters refers to an hipercafé [hypercafé] when in fact what she means is cibercafé [cybercafé].

-

[17]

Joder and coño can often be rendered as fuck or shit, although they are often not as offensive in Spanish as these English “equivalents.” Given the blasphemous nature of hostias (literally referring to the Host), it could be rendered as Christ or Jesus.

Bibliography

- Aleza, Milagros (2006): Cuestiones gramaticales y desviaciones frecuentes. In: Milagros Aleza, ed. Lengua española para los medios de comunicación: usos y normas actuales. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch, 47-101.

- Ávila, Alejandro (1997): El doblaje. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Baker, Mona (1996): Corpus-based translation studies: the challenges that lie ahead. In: Harold Somers, ed. Terminology, LSP and Translation: Studies in language engineering in honour of Juan C. Sager. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 175-186.

- Baños-Piñero, Rocío and Chaume, Frederic (2009): Prefabricated orality: a challenge in audiovisual translation. In: Michela Giorgio Marrano, Giovanni Nadiani and Chris Rundle, eds. The Translation of Dialects in Multimedia. Special Issue of Intralinea. Visited 3 August 2012, http://www.intralinea.it/specials/dialectrans/ita_more.php?id=761_0_49_0_M.

- Barambones, Josu (2012): Mapping the Dubbing Scene. Audiovisual Translation in Basque Television. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Biber, Douglas, Johansson, Stig, Leech, Geoffrey et al. (1999):Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. London: Longman.

- Bonsignori, Veronica, Bruti, Silvia and Masi, Silvia (2012): Exploring greetings and leave-takings in original and dubbed language. In: Aline Remael, Pilar Orero and Mary Carrol, eds. Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility at the Crossroads. Media for All 3. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 357-379.

- Briz, Antonio (1996): El español coloquial: situación y uso. Madrid: Arco Libros.

- Briz, Antonio (2001): El español coloquial en la conversación. Esbozo de pragmagramática. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Brown, Gillian (1977): Listening to Spoken English. London: Longman.

- Brown, Gillian and Yule, George (1983): Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carter, Ronald and McCarthy, Michael (1997): Exploring Spoken English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chaume, Frederic (2004a): Cine y traducción. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Chaume, Frederic (2004b): Synchronization in dubbing: a translational approach. In: Pilar Orero, ed. Topics in Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 35-52.

- Chaume, Frederic (2006): Screen translation: dubbing. In: Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics, 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 6-9.

- Chaume, Frederic (2007): Dubbing practices in Europe: localisation beats globalisation. Linguistica Antwerpiensia. 6:201-217.

- Comparato, Doc (1993): De la creación al guión. Madrid: Instituto Oficial de Radio y Televisión Española.

- Cornbleet, Sandra and Carter, Ronald (2001): The Language of Speech and Writing. London: Routledge.

- Corpas, Gloria (1997):Manual de fraseología española. Madrid: Gredos.

- Cuenca, Maria Josep (2006): Interjections and pragmatic errors in dubbing. Meta. 51(1):20-35.

- Dolç, Mavi and Santamaria, Laura (1998): La traducció de l’oralitat en el doblatge. Quaderns. Revista de Traducció, 2:97-105.

- Duro, Miguel (2001): ‘Eres patético’: el español traducido del cine y de la televisión. In: Miguel Duro, ed. La traducción para el doblaje y la subtitulación. Madrid: Cátedra, 161-185.

- Field, Syd (2003): The Definitive Guide to Screenwriting. London: Ebury Press.

- Flinn, Denny Martin (1999): How Not to Write a Screenplay: 101 Common Mistakes Most Screenwriters Make. New York: Watson-Guptill.

- Gómez Capuz, Juan (2001): La interferencia pragmática del inglés sobre el español en doblajes, telecomedias y lenguaje coloquial: una aportación al estudio del cambio lingüístico en curso. Tonos Digital, Revista Electrónica de Estudios Filológicos 2. Visited 3 August 2012, http://www.um.es/tonosdigital/znum2/estudios/Doblaje1.htm.

- Gregory, Michael and Carroll, Susanne (1978): Language and Situation. Language Varieties and Their Social Contexts. London: Routledge.

- Herbst, Thomas (1997): Dubbing and the dubbed text. Style and cohesion: textual characteristics of a special form of translation. In: Anna Trosborg, ed. Text Typology and Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 291-308.

- Kozloff, Sarah (2000): Overhearing Film Dialogue. California: University of California Press.

- Marzà, Anna and Chaume, Frederic (2009): The language of dubbing: present facts and future perspectives. In: Maria Pavesi, and Maria Freddi eds. Analysing Audiovisual Dialogue. Linguistic and Translational Insights. Bologna: Clueb, 31-39.

- Matamala, Anna (2008): La oralidad en la ficción televisiva: análisis de las interjecciones de un corpus de comedias de situación originales y dobladas. In: Jenny Brumme ed. La oralidad fingida: descripción y traducción. Madrid: Iberoamericana, 81-94.

- Matamala, Anna (2009): Interjections in original and dubbed sitcoms: a comparison. Meta. 54(3):485-502.

- Matamala, Anna (2010): Translations for dubbing as dynamic texts. Strategies in film synchronization. Babel. 56(2):101-118.

- McKee, Robert (1998): Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. London: Methuen.

- Myers, Lora (1973): The art of dubbing. Filmmakers Newsletter. 6:56-58.

- Padilla, Xose Antonio (2000) El orden de las palabras. In: Antonio Briz and Grupo Val.Es.Co, eds. ¿Cómo se comenta un texto coloquial?. Barcelona: Ariel, 221-242.

- Pavesi, Maria (2008): Spoken language in film dubbing: target language norms, interference and translational routines. In: Delia Chiaro, Christine Heiss and Chiara Bucaria eds. Between Text and Image. Updating Research in Screen Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 79-99.

- Pavesi, Maria (2009): Pronouns in film dubbing and the dynamics of audiovisual communication. In: Roberto Valdeón, ed. Special issue of VIAL (Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics). 6:89-107.

- Perego, Elisa and Taylor, Christopher (2009): An analysis of the language of original and translated film: dubbing into English. In: Maria Pavesi, and Maria Freddi eds. Analysing Audiovisual Dialogue. Linguistic and Translational Insights. Bologna: Clueb, 57-73.

- Pérez-González, Luis (2007): Appraising dubbed conversation. Systemic functional insights into the construal of naturalness in translated film dialogue. The Translator. 13(1):1-38.

- Quaglio, Paulo (2009): Television Dialogue. The Sitcom Friends vs. Natural Conversation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Romero-Fresco, Pablo (2006): The Spanish dubbese: A case of (un)idiomatic Friends. The Journal of Specialised Translation. 6:134-151.

- Romero-Fresco, Pablo (2009a): Naturalness in the Spanish dubbing language: a case of not-so-close Friends. Meta. 54(1):49-72.

- Romero-Fresco, Pablo (2009b): Description of the language used in dubbing: the Spanish dubbese. In: Maria Pavesi, and Maria Freddi eds. Analysing Audiovisual Dialogue. Linguistic and Translational Insights. Bologna: Clueb, 41-57.

- Ruiz Gurillo, Leonor (2000): La fraseología. In: Antonio Briz and Grupo Val.Es.Co, eds. ¿Cómo se comenta un texto coloquial?. Barcelona: Ariel, 169-189.

- Salvador, Vicent (1989): L’anàlisi del discurs, entre l’oralitat i l’escriptura. Caplletra. 7:9-31.

- Sanmartín, Julia (2006): El léxico: del recurso estilístico a la lengua de especialidad, In: Milagros Aleza, ed. Lengua española para los medios de comunicación: usos y normas actuales. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch, 245-266.

- Tagliamonte, Sali and Roberts, Chris (2005): So weird; so cool; so innovative: the use of intensifiers in the television series Friends. American Speech, 80(3):280-300.

- Taylor, Christopher (2004): The language of film: corpora and statistics in the search for authenticity. Notting Hill (1998) – a case study. Miscelánea: A Journal of English and American Studies, 30:71-86.

- Televisió de Catalunya (1997):Criteris lingüístics sobre traducció i doblatge. Barcelona: Edicions 62.

- Toledano, Gonzalo and Verde, Nuria (2007): Cómo crear una serie de televisión. Madrid: T&B Editores.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Von Flotow, Luise (2009): Frenching the Feature Film, Twice – Or le synchronien au débat, In: Jorge Díaz Cintas, ed. New Trends in Audiovisual Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 86-102.

- Vigara, Ana María (1992): Morfosintaxis del español coloquial. Esbozo estilístico. Madrid: Gredos.

- Weinstein, Nina (1982): Whaddaya Say? Guided Practice in Relaxed Spoken English. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents.

- Whitman-Linsen, Candance (1992): Through the Dubbing Glass. The Synchronization of American Motion Pictures into German, French and Spanish. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

List of figures

Figure 1

Corpus design

Figure 2

Methodology

List of tables

Table 1