Abstracts

Abstract

There has been a proliferation in recent years of bilingual inflight magazines in the Greater China region, which indirectly serve the leisure industry, providing readers on and off airplanes with non-specialist information of an entertaining nature. This paper is a preliminary study of bilingual magazines published in Hong Kong, Mainland China and Taiwan, in which attention will be paid to: (a) the stages of production, (b) their translation strategies and (c) their modes of presentation. Two questions interest us most. First, what are the specific means whereby the effects of these multi-modal texts are achieved? The second question concerns the mechanics of operation in bilingual magazine publishing. This research will show the complex interaction of several parties as well as the blending of different modes of translating in the production of bilingual inflight magazines. Our findings should help researchers and practitioners in the field understand translation production in a different context from those to which they have been accustomed.

Keywords:

- adaptation,

- adaptive translation,

- collaborative translation,

- multimodal translation,

- bilingual inflight magazine

Résumé

Ces dernières années, ont proliféré, dans toute la Chine, les magazines de bord bilingues, qui profitent indirectement à l’industrie des loisirs tout en fournissant aux lecteurs en vol ou au sol des informations générales de nature distrayante. Le présent article fait état d’une étude préliminaire portant sur les magazines bilingues édités à Hong Kong, en Chine continentale et à Taiwan, et qui s’est penchée sur trois aspects spécifiques : les étapes de la production, les stratégies de traduction et les modes de présentation. Deux questions nous intéressent particulièrement. La première concerne les moyens spécifiques grâce auxquels les effets de ces textes multimodaux sont obtenus. La deuxième s’attache aux mécanismes d’opération de la publication de magazines bilingues. Le travail réalisé souligne l’interaction complexe entre les différentes parties, ainsi que la combinaison de différents modes de traduction dans la production des magazines bilingues de bord. Nos conclusions devraient aider les chercheurs et les professionnels à mieux comprendre une pratique de la traduction distincte de celle à laquelle ils sont accoutumés.

Mots-clés :

- adaptation,

- traduction adaptative,

- traduction collaborative,

- traduction multimodale,

- magazines bilingues de bord

Article body

1. Introduction

There has been a proliferation in recent years of bilingual inflight magazines in the Greater China region, which indirectly serve the leisure industry, providing readers on and off airplanes with non-specialist information of an entertaining nature. A greater variety has been published in Hong Kong than in the Mainland and Taiwan, proving that Hong Kong is a key player in this field.[1] A diversity of formats is adopted in these magazines, with the two languages juxtaposed in innovative ways, and set against all sorts of visual materials (photos, pictures and other illustrations). The articles in the two languages can be presented either in parallel format, or back-to-back, or in alternating order, or even in a mixture of these. Our concern in this article is with magazines in the first category. In general, the two languages involved are Chinese and English, although there are also a few Japanese-Chinese-English magazines that merit attention.[2]

Based on questionnaire surveys carried out with two major publishers, information is collected for the present project on the mechanics of operation of bilingual inflight magazine publishing, with special regard to: (a) the stages of production, (b) their translation strategies and (c) their modes of presentation.

An important aspect to be considered in the production of such magazines is how the various parties work together. A substantial role appears to have been played by the editors working on the texts they receive from the translators. They act frequently as decision-makers determining the final form of a particular translation. However, the complex interaction of several parties and the blending of visual and verbal elements must also be examined to give a good picture of contemporary translation activities.

Inflight publications were chosen for this study because bilingual inflight magazines are a special category of texts that have emerged as a crucial part of the tourism and leisure industry. They not only provide “infotainment” to passengers but also help build and reinforce their “brand awareness” for the carrier, partly by showcasing its diverse operations. With bilingualism, or multilingualism, is as an essential feature, these magazines are meant to be read by passengers from more than one country. Our findings should help researchers and practitioners in the field understand translation production in a different context from those to which they have been accustomed.

2. The Collaborative Working Model

2.1. Research Procedures

The present project is of an exploratory nature, aimed at studying the operating model of inflight magazine publishers. Two sets of questionnaires with open-ended questions (refer to Appendix 1) were sent to two publishers, ACP Magazines (ACP) and Emphasis Media Limited (Emphasis Media), who agreed to participate in the research project from July to August 2008. Respondents answered the researcher in their own words. Often when questions are open-ended, respondents may lose interest halfway through and not finish it properly. However, respondents from the two companies were very supportive and helpful, providing detailed answers to virtually all the questions asked.

ACP and Emphasis Media are both well-established companies that produce some of the best known bilingual inflight magazines for airlines in Asia. ACP is Australia’s leading magazine publisher and a specialist in producing bilingual publications. It publishes Discovery for Cathay Pacific Airlines, Silkroad for Dragonair, Qantas for Qantas Air and KiaOra for Air New Zealand. For our research project, the focus is on Discovery and Silkroad because they are bilingual publications directed at travelers in the Greater China region:

Discovery is Cathay Pacific’s flagship magazine. All display types, including headlines, captions, introductions and pull quotes, etc., are given in both English and Chinese. Feature stories in Chinese and English are included in each issue, though not in parallel format, as with regular departments. English feature stories are accompanied by a precis in Chinese while Chinese features are accompanied by a precis in English. In addition, regular departments such as “Discover Hong Kong,” “Discover The World,” “Discover Hotels,” “Discover Wine/Spirits,” “CX Pages,” etc., are presented in both languages.

Silkroad is the Dragonair flagship magazine. The airline flies mostly into and out of Mainland China; therefore the content is in both English and Chinese. According to the publisher, the English copy used to be printed first, with the Chinese version following. Today, however, the two languages enjoy equal status and are run alongside each other, either in parallel columns or in top-bottom format. On the whole, bilinguality is more prominently featured here – in fact on every page – than is the case of Discovery.

Emphasis Media is an expert in producing multilingual inflight magazines and has over 35 years of experience in providing publishing services for the travel industry. Serving more than 50 airlines, the company puts out over 13 publications for seven clients – many of them feature more than one language. For our research project, the focus is on Dynasty and Hong Kong Airlines because they are bilingual publications directed at travelers in the Greater China region:

Dynasty, the inflight magazine of China Airlines, is a trilingual publication in English, Chinese and Japanese. Emphas Media helped China Airlines to publish Dynasty for 13 years from 1995-2008. The magazine is meant to entertain and appeal to a more diverse group of passengers, demographically and culturally speaking, since the airline serves Taiwanese, American and Japanese travelers. The magazine provides a mix of articles from Taiwan and around the world. The Chinese language section focuses on the many facets of Taiwanese life, including the traditional, rural and modern aspects of life on the island. This forms its core. The English and Japanese sections show a similar orientation, but they are shorter and relegated to the back before “China Airline News,” “Inflight Information” and other pages on “Health,” “Climate” and “Arrival.”

Hong Kong Airlines is published for Hong Kong Airlines which, together with its partner Hong Kong Express, serve the East Asian region, including such countries as Vietnam, Malaysia, Japan, Thailand, South Korea, the Philippines and Hong Kong.

2.2. Stages of Production

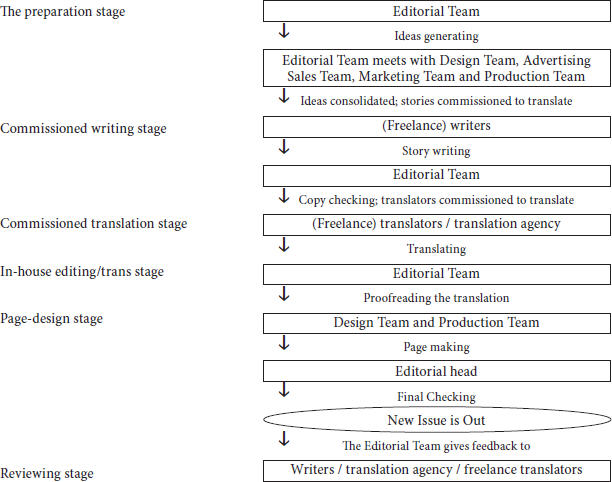

On the basis of responses provided by the two publishers, we can construct a flow-chart showing the six stages in the production of a bilingual inflight magazine.

Figure 1

The production of a bilingual inflight magazine

2.2.1. Preparation stage

Work on an issue of the bilingual inflight magazine starts with several editorial meetings held to discuss the items for an upcoming issue. The editorial team normally consists of an Editor-in-Chief who oversees the production of every issue while taking charge of the entire editorial department, as well as full-time editors and sub-editors who are responsible for ensuring the quality of commissioned stories, checking commissioned translations and writing introductions, captions and headlines.

None of the magazine publishers set the theme of the issue. The Editor-in-Chief of ACP pointed out that successful magazines do not have themes but offer a wide variety of stories of different lengths and treatments. This appeals to the clearly defined readership. An issue may highlight a particular topic with ample space devoted to it but generally issues are never themed. Emphasis Media’s Editorial Director Innes Doig and Managing Director (Chinese) Amy Lo note that they do not give each issue a theme because they don’t want to limit the content. Instead of setting a theme, the publishers are concept-driven in using stories that promote the identity of the client’s brand image. Once the ideas for an upcoming issue are decided, the Editorial Head will discuss it with the design, production, advertising sales and marketing staff. He must ensure that the design and production teams can provide visuals that support and integrate into the articles. The editorial team also works closely with the advertising team to make sure they can promote the publication to advertisers.

2.2.2. Commissioned writing stage

After deciding on the ideas for an upcoming issue, the best writers at the locations concerned will be commissioned to write the stories. Neither ACP nor Emphasis Media hires full-time writers for the writing assignments. The ACP has a large pool of experienced writers from different cities. According to William Fraser, Editor-in-Chief at ACP, they edit Discovery with frequent business travelers in mind. Because they often visit a particular destination on multiple occasions, they are quite familiar with the city and surrounding area. They need to be supplied with the most up-to-date and accurate information possible – preferably material not available from the standard travel guides.

2.2.3. Commissioned translation stage

Most of the stories are first written in English. After receiving the story from a commissioned writer, the editorial team will then fact check and sub-edit it in-house before giving it to a translation agency or translator to render into Chinese. The nature of the publisher-translator collaboration varies according to the agreement already signed with the airline client. The publisher either works with a translation agency assigned by the airline client (ACP), or with its established network of experienced freelance translators (Emphasis Media).

ACP works with Invospan, a preferred Cathay Pacific translation agency, on an agreed corporate rate per word. Because of the volume of translation that Invospan often has to do, late copies must sometimes be sent to freelance translators, although the cost is higher. Copy deadlines are fixed at two months before the publication date, which falls on the first of each month. For this reason, ACP must be alert to time-sensitive material in the stories. On the other hand, Emphasis Media has a pool of translators who have worked closely with the editorial team for a long time and whose translation skills meet Emphasis Media’s expectations.

The responses gathered for the present study show that publishers normally require translators to do some research in advance. For example, Emphasis Media requires their translators to conduct research on any subject covered before working on a translation. The Editorial Head notes that translators must either read more information online or go to libraries for reference books on related subjects in order to correctly translate certain details. They may also need to do some market research such as talking to professionals in the relevant fields.

Publishers also ask translators not to follow the original too closely. ACP’s guidelines are that: (a) translators should convey the meaning, tone and intent of the content and (b) the text should read naturally and as much as possible as though it were written in the translated language. Similarly, for Emphasis Media, literal translation is generally not encouraged because people of different languages and cultures tend to view things from different perspectives. Some rewriting to cater to different cultures is generally preferred. Section 3.1 gives some examples to illustrate these points.

2.2.4. In-house editing and translation stage

After the completed translations are received by the editorial department, sub-editors are set to work in checking their quality. This practice is adopted by bilingual inflight magazine publishers to ensure the translations enhance the airline client’s policy and image. At ACP, the vetting is done by Chinese sub-editors for quality and accuracy. However, all headlines, introductions and captions are translated in-house. This requires skilled and experienced language experts who can capture the essence of headlines succinctly and creatively, often using subtle word play that echoes the original.

2.2.5. Page-design stage

It is essential that the editorial team work together with the design team. There is a preference in bilingual inflight magazine publishers for full-time permanent designers trained in graphic design and with prior experience in the production of magazines, newspapers or in creative agencies. The editorial and design teams must meet weekly to discuss the presentation and keep track of the progress. This is very time-consuming and requires designers with strong technical knowledge of software as well as a good command of both English and Chinese – again, not easy to find.

2.2.6. Reviewing stage

Apparently the production of an issue ends after the finalized version has been proofread, for then the version will be sent off to be printed. But occasionally comments are solicited about the magazine, and this constitutes a “reviewing stage.” In this stage, feedback about the quality of the entire publication is gathered, and specific comments on the translations are also obtained. The comments are passed on to the translation agencies or freelance translators on a regular basis. This enables the agencies to monitor the performance of the translators they employ, while the translators can seek to improve themselves for future work by correcting specific deficiencies. The editorial team will also periodically study the feedback and make appropriate changes affecting all aspects of production.

2.3. Resources and Costs

Our research reveals that the two publishers tend to use freelance translators for translation assignments. This is partly due to the difficulty of recruiting proficient and experienced translators, and also because of the high costs involved. For ACP, it is difficult to recruit qualified, proficient and experienced translators who can work swiftly and accurately. According to ACP’s Fraser, they have a demanding client which necessitates the system of checks and balances they have in place. They constantly monitor quality and performance of both the translators and the translation agency they use. Emphasis Media also finds it difficult to recruit a proficient translator. The Editorial Head explained they need someone to be highly skilled, detailed-oriented and clearly understand their requirements. He notes that many translators in the market can only provide literal translations.

3. Translation and Bilingual Inflight Magazines

3.1. Adaptive Translation

Neither ACP nor Emphasis Media considers faithful translation a useful or commendable method for their magazines. ACP’s Fraser emphasizes that “translations should not be word for word or in any way literal. They should convey the meaning, tone and intent of the content and read naturally and as much as possible as if written in the translated language.” In general, it is the adaptive method of translation that takes precedence.

Bastin points out that adaptation is “a type of creative process which seeks to restore the balance of communication that is often distrupted by traditional forms of translation” (Bastin 2009: 6). According to Vinay and Darbelnet (1995: 338), adaptation is defined as “the translation method of creating an equivalence of the same value applicable to a different situation than that of the source language.” Adaptation is used:

in those cases where the type of situation being referred to by the SL message is unknown in the TL culture. In such cases translators have to create a new situation that can be considered as being equivalent. Adaptation can, therefore, be described as a special kind of equivalence, a situational equivalence

Vinay and Darbelnet 1995: 39

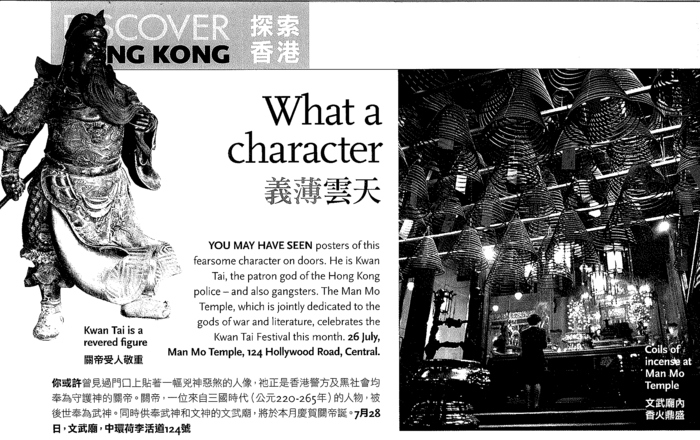

What Vinay and Darbelnet have not mentioned in their definition of the adaptive method is that it may not be a strategy decided upon by the translator alone. Bastin (2009) has suggested that the decision to carry out a global adaptation, which is a type of adaptation determined by factors outside the original text and which involves a more wide-ranging revision, may be taken by the translator or by external forces such as the publisher’s editorial policy. Our example of bilingual magazine translation shows that adaptation might have been the choice of the translator, or the editors, or the entire production team. Three examples will suffice to illustrate the point. The first two examples are both from the July 2008 issue of Discovery. In the “Discover Hong Kong” section, there is a short note telling the reader that Hong Kong is celebrating the Guandi (often called the Warrior-God) Festival during that month (Figure 2). Guandi is a historical figure from the Three Kingdoms period (AD 220-265) already elevated to become the patron god of Hong Kong policemen as well as gangsters. The English headline reads: What a character, but it is translated into Chinese as yibo yuntian (integrity in the high regions of the clouds). Obviously a literal translation would not have created as strong an effect on the Chinese reader as the original headline has on English readers. Given what ACP’s Fraser has said (and quoted earlier in this article) about the in-house editors taking responsibility for the translation of the headlines, the final version may not have been the commissioned translator’s.

Figure 2

What a character, adapted from Discovery 2008 (7):12[3]

The second example involves a six-page story featuring five of India’s top female entrepreneurs in a section entitled “Discover Entrepreneurs” in the same issue. Each page features an interview with one of these entrepreneurs. The writer first introduces the interviewee’s background, then elaborates on her achievements, including some quotations from the interview. In the translation, none of the quotations can be found and the translator resorts to extensive summarizing. As the feature article is ostensibly meant to tout the success of five of India’s top female entrepreneurs, one assumes that the rather lengthy quotations would not only be redundant but likely too tiresome to be enjoyed by Chinese readers of the translation.

Another example is found in a feature story in the August 2008 issue of Dynasty. The feature introduces Kinmen, historically a military bastion in Taiwan and now a tourist mecca. The author sets out to tell how the place has been changed from battlefield to new tourist destination, and shares the historical issues, recent developments and attractions of the place as well as his personal opinions with the reader. However, the English translation only covers the attractions of Kinmen and most of the writer’s personal feelings and viewpoints are missing.

Since the actual textual changes made by the various parties during the magazine production stages have been irretrievably lost, we will never know if the deletions were made by a single party.[4]

It is well understood that adaptation is not a favored translation strategy for the source-text oriented theorist. However, some flexibility is in order given that a translation is also measured by the needs it intends to serve. Christiane Nord has rightly stressed the importance of what the German functionalists have called skopos (Nord 1991). Bastin, too, has said that:

The study of adaptation encourages the theorist to look beyond purely linguistic issues and helps shed light on the role of the translator as mediator, as a creative participant in a process of verbal communication

Bastin 2009: 6

ACP publisher Peter Jeffery also corroborates this view, albeit indirectly. With perspicacity, he notes that “the role of a bilingual inflight magazine is to provide editorial content that can be read by the readers of both languages. The content does not have to be identical but must appeal to both audiences.”

Two examples from the June 2009 issue of Discovery illustrate this point. In the “Discover Taiwan” section, there is a feature introducing readers to some hot favorites in Taipei. The writer describes Dinghao Square as a “great place to people watch – just grab a seat on a bench and observe the trendiest Tapiei residents walk on by.” The word people is translated as Taipei Xingnan Meinu (metrosexuals and pretty women living in Taipei). The phrase is a kind of Chinese colloquial expression widely applied in spoken language to describe the physical attractiveness and trendiness of men and women. The translation seems to make the text more relevant and indigenous to Chinese readers.

Another example is also found in the June 2009 issue of Discovery. In the editor’s note, the editor, Kate Whitehead, starts by saying that “every seasoned traveler knows that the best way to explore a city is with the help of a local resident. So for our guide to Paris, we asked designer agnes b. to show us around her favorite spots.” The full name of “agnès b.” is Agnès Andrée Marguerite Troublé. She is a French fashion designer. In the Chinese translation, a local resident is translated as shi tu lao ma (an old horse who knows the way).

3.2. Multimodal Translation

Writers have long noted how visual elements in a printed text can be usefully deployed to carry across a verbal message, and translators, as multimodal text producers, have utilized these to their advantage. Whereas in informative essays, visuals like charts, diagrams or graphs help reference an argument, narratives are often accompanied by pictures and illustrations for effect; but in leisurely publications photos and maps are incorporated to attract readers’ attention.[5] Of course there are the basic visual components of texts like font sizes, typefaces, spacing, margins, headings, even the formatting of entire pages. In scholarly publishing, the visual elements are usually neglected, due partly to the privileging of verbal over visual information, and to the view that the writer’s sole function is to write (Landow 2006: 87). Yet this position is not tenable for contemporary magazines and Web-publications. Almost all leisurely publications like inflight magazines have resorted to all kinds of pictorial embellishment that gives additional power to the text, in bilingual magazines no less than monolingual ones.

Christian Matthiessen (2001) has noted that multimodal presentations are made up of complementary contributions from different semiotic systems. Matthiessen analyzes a descriptive passage by John Ruskin that “verbalizes” William Turner’s painting “The Slave Ship,” then Martin Emond’s pictorial representation of a descriptive passage from Macbeth. Through these he demonstrates how the boundaries can be crossed between the linguistic and the non-linguistic. In the case of bilingual magazines, however, the situation is more complicated. The verbal and visual are simultaneously presented, with the latter serving as a “translation” in a different semiotic mode of the verbal text. So both texts exist in an original text-target text relationship, although sometimes it is hard to say which is the source, and which the translation. For the reader with facility in both the languages used, there is additional pleasure in being able to decipher the similarities, as well as the disparities, between the parallel texts.

3.2.1 Basic Principles

As mentioned earlier, there are a few basic options with regard to the display of the Chinese and English texts in a bilingual inflight magazine. First, the stories in both languages can appear on the same page, in juxtaposition. Second, the magazine can start in English and then be flipped and the Chinese starts from the other end of the magazine. Third, the stories can be run successively – entirely in English first, and then in Chinese. Needless to say, the third kind of display is the least satisfactory, as it requires two sets of artwork and designs for the same story; this doubles the cost and time spent. According to ACP’s Fraser, the only time he has ever seen this done is with a magazine called Benchmark which deals with managed funds and was bought by Readers’ Digest. One may also query the usefulness of dual-language publishing, since most readers are probably not bilingual anyway, while bilingual readers will presumably not want to peruse the same piece twice. However, what is often ignored in these arguments is that the bilingual magazine gives readers with dual-language choice of reading one article in Chinese and the other in English, as preferred.

To begin with, there are technical problems to deal with. Because a Chinese text takes approximately 55 percent less space than an English text, the editorial and design teams must use visuals to accomodate the difference in length. Stories must sometimes be cut to fit the design space. The English is usually cut first and then the Chinese is adjusted to accuarately reflect what appears in English. The principle followed is that changes made to one language must be reflected in the other. Thus, sometimes when a feature story is shortened, entire sections will have to be removed. Finally, any reference to the excised material must also be removed from the précis, if there is one.[6]

The choice of fonts also represents a difficult decision. The font must be available in both English and Chinese versions and there must be a wide variety in the font family, including the regular, book, bold, italic and condensed versions. The reason is that often there is no Chinese translation for personal names, hotel or restaurant names or film titles, and these must be included in Chinese as well as English. Inflight magazine publishers normally leave names in foreign languages untranslated. In the June 2009 issue of Discovery, names such as agnès b (Agnès Andrée Marguerite Troublé), John Simm, Kelly MacDonald; brand names such as BlackBerry, Vodafone, Canon, Nintendo; hotel names such as The Lela Kempinski Gurgaon and Novotel Barossa Resort are not translated. They are presented in English or in their original languages. The challenge here is that the English words placed within the Chinese text must match those in the original text as closely as possible in size and kerning (the space between the characters). Because Chinese characters are all the same size while English characters vary in size – for example, the letters i, n, and m have different widths – the computers need to automatically adjust the spacing. Within the Chinese text, if the English words appear with the same spacing as the Chinese ones, it will look awkward.

Another example is from the August-September 2008 issue of Hong Kong Airlines, in which the English text appears on the page to the left and the Chinese text, on the right. While the former is virtually identical to any page from an English-language magazine, the latter is more exciting because of the hybrid mixture of Chinese characters with English words. The translators and editors have decided to leave untranslated the English names of the sightseeing spots and leisure establishments in Malaysia, and the same treatment is extended to the addresses included in the text to direct the traveler to the places in question. Words in Malay are included and transliterated into English for the non-Malay-speaking reader: Selamat pagi (for good morning) and Terima Kasih (for thank you). They are conspicuous not just because of the way they are juxtaposed against the Chinese characters, but also because they belong to a third language. Furthermore, as the reader’s eyes move from one page to the other – as required to relate the photo images to the textual information provided – they will meet a dazzling array of verbal and visual stimuli, something much less likely in a monolingual publication.

Aesthetically, it is very important that texts in both languages do not detract from each other. This means the editorial and design teams must continually work hard to produce effective layouts where two languages are present on each page. Fortunately, because Chinese and English have different typographies it is possible to juxtapose the two texts to make a visual impact, so that the text in the unknown language can become decorative for the monolingual reader. Also vital is to avoid putting too many different elements (languages and images) on one page, so it is not cluttered. A problem common to many bilingual publications is that the pages are densely packed with words since every idea is repeated in two languages. This of course makes for less satisfying results.

Since the illustrations in a printed text do deliver messages to their readers, it all the more important for the translators, editors and designers to work together to blend the visual and verbal elements. A story from the August-September 2008 issue of Hong Kong Airline is an example. The story is about railway locomotives used in Japan from the nineteenth century to the present. The page designer gives a visual dimension to the narrative by incorporating two photos – one of a miniature train that is both a toy and a collector’s item, and the other of a cat-eared “Fastech 360S” train yet to be launched into service – and a painting of a railway station in the Meiji period. The reader simultaneously reads about the past and learns about the future, aided by the visual elements, which are ingeniously chosen to highlight the twin themes of the feature article.

3.2.2. Examples of Actual Practice

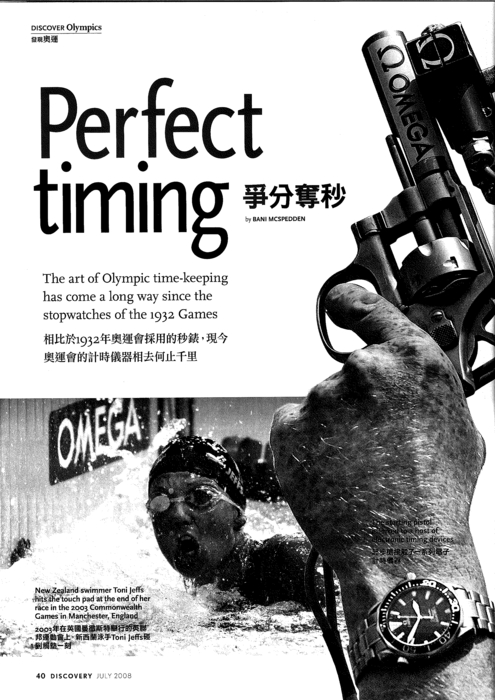

Going beyond general principles, we can analyze several instances of actual “translational” practice. Figures 3a and 4b below are typical of most bilingual texts in the magazines we surveyed, with texts in the two languages presented either in left-right format or with one above the other. Dealing with the subject of how speed can be measured in sports events like the Olympics, this feature article from Discovery, appropriately entitled “Perfect Timing,” makes use of a series of photos from Olympic competitions to lend emphasis to the theme of how “the art of Olympic time-keeping has come a long way since the stopwatches of the 1932 Games” – as stated in the subheading. These are photos showing: (a) swimmer Toni Jeffs hitting the touch pad at the end of her race in the Commonwealth Games in Manchester and (b) the Beijing Olympics countdown clock in Tiananmen Square. All the images are tied to the central theme of the piece, namely that attaining precision in measuring time is most arduous yet still to be wholeheartedly striven for. They visually “translate” the text already presented bilingually in English and Chinese.

Figures 3-4

Perfect timing, adapted from McSpedden, 2008 (7): 40-41[7]

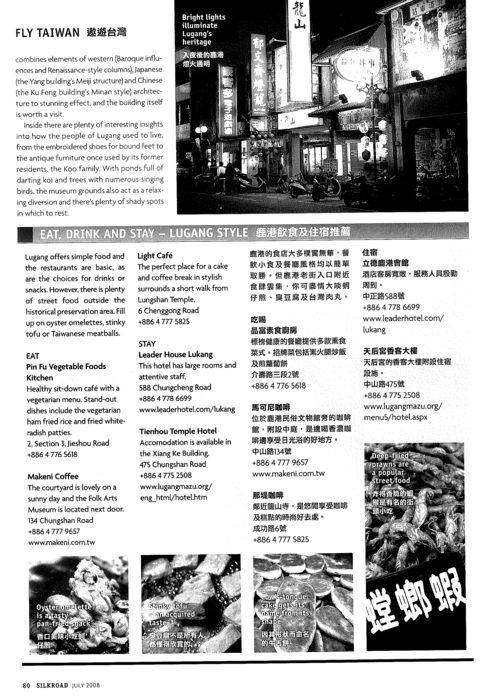

At the bottom of figure 5, from the July 2008 issue of Silkroad, pictures are displayed for four famous kinds of “street-food” in Lugang, a small provincial town in Northern Taiwan: oyster omelette, stinky tofu, cow’s-tongue cake and deep-fried prawns. The English and Chinese texts, one above and the other below, are superimposed on the pictures, to direct the reader’s attention to what is special about each delicacy. Thus, “oyster omelette is a tasty pan-fried snack,” “stinky tofu – an acquired taste,” “cow’s-tongue cake gets its name from the shape,” and “deep-fried prawns are a popular street food.” One may say that the verbal messages are corroborated by the lively photographs, but it is equally true to say that the meaning of the pictures is brought out by the verbal texts. In other words, the verbal and the visual are immediate “translations” of each other; they work simultaneously to generate a spontaneous response from the reader. This case exemplifies the way in which the page designer (who came up with the idea) and the editors (who translated the captions) of Silkroad have collaborated to create a bilingual as well as multimodal text.

Figure 5

Eat, drink and stay – Lugang Style, adapted from Silkroad 2008 (7): 80[8]

4. Conclusion

Little research has been carried out so far about the production of bilingual inflight magazines. Our study of bilingual inflight magazines published in the Greater China region shows that translation is a collaborative effort. The roles played by editors and page designers are as important as that played by translators. In those parts of the production chain where the initial translators are not involved, there may be the inclusion of translated texts (such as passages added later, and titles and captions for the articles) done by editors. In fact, as clearly shown by the production stages of a bilingual inflight magazine, the editors must be pivotal figures ultimately instrumental in shaping the translated text. Of equal billing is the page designer who can be viewed as a “translator of sorts” in having to juggle all the visual elements meant to accompany, illustrate and amplify the message carried in the two languages. Close “textual” analysis of any page from a bilingual publication shows this. Ultimately, rethinking should be directed toward developing a new model of the translator at work in the leisure industry, or in the context of bilingual magazine production.

Appendices

Annexe

Appendix 1. Questionnaire Survey

The questionnaires were sent to ACP on 4 July 2008; replies were received on 8 July 2008. They were sent to Emphasis Media on 8 July, 2008, and responses were returned to the researcher on 28 August 2008.

A. Questionnaire for the senior management:

How do you position the bilingual inflight magazines you are producing?

What is the “attention-getter” of the magazines?

What is the mode of operation?

What is the highest cost incurred by your company in running a bilingual inflight magazine? Why is it the highest?

Do you think that bilingual inflight publications are equipped to play the role of provider of leisure information?

To what extent do you agree that bilingual inflight magazines are here to stay; that is, will they always be a part of the publishing and tourism industry? Why?

Will your company seek feedback from readers in an attempt to expand its readership?

What is your opinion about current bilingual inflight publications?

B. Questionnaire for the heads of editorial departments:

How do you assign writing and translation assignments?

Is the writing and translation done by one and the same person?

What strategies do your translators use?

What is the most effective translation strategy for bilingual inflight magazines?

Do you think that recruiting a proficient translator is a most difficult task in running a bilingual inflight magazine? Why?

As the presentation of a bilingual inflight magazine is quite different from that of monolingual ones, could you explain how the visual and verbal elements are intermeshed?

Do the editors need to work with the designers in this effort?

How do you decide on the theme of each issue?

Does the editorial department need to communicate with other departments in matters of theme design?

Is there a specific department that handles all your translation work?

What kind of team members (for example, freelancers, full-time and part-time staff) do you employ?

What sort of background do the designers have?

Are they permanently stationed in the company? Or is there a design company that you work with on an issue-by-issue basis?

What are the principles of page design?

Do the authors and translators take part in deciding on matters of design?

What part does the typesetter play in the production process?

How does the company make sure its image is promoted by the magazine?

Remerciements

The author would like to express sincerest gratitude to Professor Leo Tak-hung Chan for his invaluable guidance, advice and help. The author also wishes to thank the following for providing insightful input and thorough answers for this research project: Adrian Andaya, Senior Marketing Manager, Emphasis Media; Innes Doig, Editorial Director, Emphasis Media; Amy Lo, Managing Editor (Chinese), Emphasis Media; Peter Jeffery, Hong Kong Managing Director, ACP Magazines; William Fraser, Editor-in-Chief, Discovery and Silkroad; Kate Whitehead, Editor of Discovery and Silkroad. In addition, the author is grateful for the generosity of the editor of Discovery and Silkroad for granting permission to reproduce the images from their magazines.

Notes

-

[1]

Magazine publishing has lagged behind considerably in Mainland China, while in Taiwan monolingual magazines have largely dominated the market. For a discussion of the Mainland scene, see Zhang (2001).

-

[2]

There are innumerable examples of bilingual inflight magazines involving other language pairs – for example, Spanish and English are used in Ronda Magazine, the publication by Iberia Airlines. There are also a wide range of monolingual magazines (like the one by Air France).

-

[3]

The image is an article entitled “What a character” adopted from Discovery 2008(7):12. The name of the writer does not appear in the text. The article provides the English text and then the Chinese translation.

-

[4]

The author has sought, in vain, to obtain the various intervening drafts of texts included in the two magazines being analyzed for the present project.

-

[5]

For studies of book design, readers are referred to Lee (2004) and Zappaterra (2007). On the principles and practice of magazine design, see White (1982) and Rivers (2006).

-

[6]

For example, Discovery accompanies English language stories with a précis in Chinese and vice versa.

-

[7]

Bani McSpedden (2008): Perfect timing. Discovery. 2008(7):40-41.

-

[8]

The image is an article entitled “Eat, drink and stay – Lugang style” adapted from Silkroad 2008(7):80. The name of the writer does not appear in the text. The article starts in English and then with Chinese translation.

Bibliographie

- Anonymous (2008): What a character. Discovery. 2008(7):12.

- Anonymous (2008): Eat, drink and stay – Lugang style. Silkroad. 2008(7):80.

- Bastin, Georges L. (2009): Adaptation. In: Mona Baker and Gabriela Saldanha, eds. Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, 3-6.

- Landow, George P. (2006): Hypertext 3.0: Critical Theory and New Media in an Era of Globalization. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lee, Marshall (2004): Bookmaking: The Illustrated Guide to Editing/Design/Production. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Co.

- Matthiessen, Christian M.I.M. (2001): The Environments of Translation. In: Erich Steiner and Colin Yallop, eds. Exploring Translation and Multilingual Text Production: Beyond Content. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 41-124.

- McSpedden, Bani (2008): Perfect timing. Discovery. 2008(7):40-41.

- Nord, Christiane (1991): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam: Rodopi Editions.

- Rivers, Charlotte (2006): Mag Art: Innovation in Magazine Design. Mies: RotoVision Book.

- Vinay, Jean-Paul and Darbelnet, Jean (1995): Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A Methodology For Translation. (Translated and edited by Juan C. Sager and Marie-Josée Hamel) Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- White, Jan V. (1982): Designing for Magazines. New York and London: R.R. Bowker Co.

- Zappaterra, Yolanda (2007): Editorial Design. London: Laurence King Publishing.

- Zhang, Bohai (2001): Magazine Publishing in China. Publishing Research Quarterly. 17(2):38-42.

List of figures

Figure 1

The production of a bilingual inflight magazine

Figure 2

What a character, adapted from Discovery 2008 (7):12[3]

Figures 3-4

Perfect timing, adapted from McSpedden, 2008 (7): 40-41[7]

Figure 5

Eat, drink and stay – Lugang Style, adapted from Silkroad 2008 (7): 80[8]