Abstracts

Abstract

The essay considers the geography and economic significance of the sex trade in Victoria, British Columbia, a city that has historically associated itself with notions of gentility and images of English country gardens. The essay problematizes that image. Influenced by the spatial turn in the Humanities and informed by Henri Lefebvre’s ideas on the production of space, the production of prostitutional space is the focus of this piece. The essay discusses how and why space was demarked by local authorities for what Foucault called “illegitimate sexualities.” It delineates geographies of sexual commerce in Victoria and invites questions about sexuality in other Canadian and American cities, as well as other British colonial cities. This piece is a tentative step towards mapping moral geographies in nineteenth century cities and placing them within a broader temporal, societal, spatial, and theoretical framework.

Résumé

La présente étude explore la géographie et l’importance économique du commerce sexuel à Victoria (Colombie-Britannique), ville qui s’est traditionnellement proclamée bourgeoise, à l’image de ses parfaits jardins anglais. Cette étude remet en question cette image. Influencé par le « tournant spatial » en sciences humaines, et inspiré par les idées d’Henri Lefebvre sur la production de l’espace, nous nous intéressons à la production de l’espace « prostitutionnel ». En particulier, nous nous demandons comment et pourquoi un espace a été démarqué par les autorités locales pour ce que Foucault a qualifié de « sexualités illégitimes ». Nous délimitons les aires du commerce sexuel à Victoria et nous nous questionnons sur la sexualité dans d’autres villes canadiennes et américaines, ainsi que d’autres villes coloniales britanniques. Cette étude se veut une tentative de cartographie des géographies morales dans les villes du XIXe siècle pour les replacer dans un cadre temporel, sociétal, spatial et théorique plus vaste.

Article body

I

In 1861, a resident of Victoria, on Vancouver Island, addressed a letter to the editor of a local newspaper on a topic that vexed some of his colonial compatriots: Prostitution. “I think you will allow that in a town containing a large predominance of men, and men who, by their mode of life … are precluded from marriage, it is almost, if not totally impossible, to prevent prostitution.”[1] It was a prescient comment. The colonial capital of Vancouver Island (and afterwards the capital of the united colony of British Columbia), was an entrepôt for the Cariboo goldfields and an important seaport. The miners and sailors who sojourned in Victoria accounted for its masculine character, a character that was conducive to sexual commerce. During the early colonial period, the sex trade involved aboriginal women and non-aboriginal men. Censorious clergymen and civic reformers depicted aboriginal prostitutes as “wretched women”; the white men who consorted with them were “dissipated” and “degraded.”[2] However, most commentators who were offended by the sex trade assumed that it was a temporary blight, something that would attenuate once Victoria shed its frontier image and developed into a more mature community. It was also assumed that prostitution would wither when native people embraced Christianity, when the number of white women increased, and when those women and erstwhile transient white men married, had children, and established homes and families. When those conditions were met, the moral tone of Victoria would be raised and vice would be extirpated. But that did not happen. Although the racial complexion of the sex trade changed, the trade itself continued, unabated. In fact, the sex trade burgeoned as Victoria developed into a modern North American city. By the 1880s, the metropolitan centre of British Columbia — Victoria — was one of the largest sexual emporiums in the Pacific Northwest. The sex trade continued to grow over the next decade and by the turn of the twentieth century it was a major component in Victoria’s economy. The sex trade was not curtailed until just before World War I, when a sequence of social, political, and economic forces restricted sites of sexual commerce.

This paper considers the geography and economic significance of the sex trade in Victoria during the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century. The paper is informed by recent scholarship that has been associated with a “spatial turn” in the Humanities and Social Sciences.[3] But it is not simply an exercise in placing dots on a map.[4] I am interested in what Henri Lefebvre described as the “production of space.” “Space,” Lefebvre observed, “is permeated with social relations; it is not only supported by social relations, but it is also producing and produced by social relations.”[5] In this paper, I consider the production of prostitutional space. Further, this paper considers what Lefebvre called “the illusion of transparent space,” a notion that erroneously regards space simply as an unmediated point on the earth. Lefebvre argued that “the homogenizing tendency of transparent space is always threatened by the persistence of difference. There is always an ‘elsewhere’ that does not merely lie outside the centre but radically striates it.”[6] That elsewhere, that ‘other,’ existed in spaces occupied by brothels and other places connected to the sex trade in Victoria. This paper will consider how and why space was demarcated by the state for what Foucault calls “illegitimate sexualities.”[7] As well, this paper considers the contradictions of place in a Victorian city and the juxtaposition of conflicting moral geographies. It alludes to Gillian Rose’s concept of paradoxical space and to the imagined space that Foucault called heterotopia.[8] This study is a tentative step towards mapping moral geographies and placing them within a broader temporal, societal, spatial, and theoretical framework.

II

Victoria was founded as a Hudson’s Bay Company post in 1843. It was incorporated as a city in 1862, in the midst of the Cariboo gold rush.[9] The gold miners who sojourned in Victoria were important to the local economy. They liked to spend their time and money in the city’s dance houses, where they could dance high-spirited reels with aboriginal women. Dance houses were not licensed to sell liquor, but booze was available illicitly in all of them. Neighbours sometimes complained about the raucous fiddle music resonating from the wooden halls, and about the “obscene and profane language” of revellers, as dance house patrons stumbled drunkenly into the streets at closing time.[10] But dance houses, along with theatres and saloons, were nevertheless licensed as legitimate places of entertainment. Proponents argued that if the dance houses were closed, miners would sojourn in Puget Sound ports or San Francisco.[11]

Dance houses were seasonal establishments. They opened during the winter when the miners were in town and closed in the spring when the men headed across the Strait of Georgia to the goldfields on the mainland. Geographically, dance houses are not well documented, but the largest dance house in Victoria stood at the northern end of Store Street, near the municipal gas works, in an industrial, sparsely-populated section of Victoria. The unidentified proprietor of this dance house considerately located it there so that it would not cause an “annoyance” to the neighbours. But critics, such as Amor de Cosmos, founding editor of the British Colonist newspaper and a future premier of British Columbia, were not impressed. “Remote from liquor saloons more liquor will be supplied clandestinely than ever before,” the editor wrote in a story about the new dance house. “We may consequently expect a proportionate amount of evil.”[12]

Prostitution was an adjunct or ancillary activity to the dance houses. De Cosmos and some of his readers were offended by the fact that white men cavorted and consorted with native women in these places. “A dance house is only a hell-hole where the females are white,” de Cosmos declared, “but it is many times worse where the females are squaws.” Thus, on “moral grounds” the dance houses were denounced as “dens of infamy,” “sinks of iniquity,” and “hot beds of vice and pollution” in the pages of the British Colonist.[13]

As Adele Perry and Jean Barman have noted, negative attitudes towards aboriginal women may have been rooted in fears about aboriginal sexuality and concerns that the moral fabric of this outpost of Empire would be undermined by miscegenation.[14] Barman has also argued that missionaries, clerics, and “other self-styled reformers” derived a “moral gratification” by chastising aboriginal women who attended dance houses and depicting them as sexual transgressors.[15] However, the fact was, most of the women who traded sexual services for money in Victoria during the early colonial era were aboriginal. The documentary evidence is extensive, although interpretations of the evidence are open to debate. Some historians have noted that the exchange of gifts for sexual services was not taboo in aboriginal societies, so what appeared to be prostitution to colonial newcomers was not morally reprehensible to indigenous people; other historians have represented the exchange of sex for money as a legitimate form of entrepreneurial activity, one that empowered aboriginal women and enabled them to acquire material goods and advance their status within their traditional communities.[16] Even contemporary observers were not quite sure how to interpret the situation. Some observers thought that aboriginal women who engaged in prostitution in Victoria were slaves, who were coerced into the sex trade by their Lekwammen (Songhees) captors. (The colonial enclave of Victoria was located on Lekwammen territory.) Other observers suggested that aboriginal women who worked as prostitutes in Victoria came from Kwakiutl communities on the north end of Vancouver Island, Nuu-chah-nulth communities on the west side of the Island, and Tsimshian villages on the northern coast of British Columbia.[17]

The motives, identities, and origins of these women were irrelevant to colonial officials who regarded aboriginal prostitutes as a nuisance. On several occasions, Victoria’s chief of police was instructed to disperse congregations of “Indian prostitutes” on Store Street, opposite the Songhees village site on the western side of the harbour.[18] Local newspapers frequently commented on the prevalence of aboriginal prostitutes in Victoria and the non-native men who consorted with them. In a leading article in the Vancouver Times, a Victoria newspaper, the editor complained that “Indian prostitutes” and their customers had “polluted the moral as well as the physical atmosphere” of Victoria. “The hovels in the alleys and bye-ways of the town are filled by these wretches and their degraded male companions, whose filth and obscenity annoy the whole neighbourhood.”[19]

The description was lurid, but the situation that offended editors of the British Colonist and the Vancouver Times was transitory. Aboriginal involvement in the sex trade did not last long. As Barman and other historians have noted, a complex series of policies and circumstances created a social gulf between aboriginal women and non-aboriginal men in British Columbia, a gulf that grew ever wider as the colonial era came to an end. Native women were deterred from sexual relations with white men by native men, missionaries, and government agents.[20] The social and sexual space between natives and non-natives in Victoria also increased, as the Songhees Indian village was segregated from the city of Victoria.[21] By 1871 — when British Columbia joined Confederation and Victoria became a provincial capital — the aboriginal complexion of the sex trade was much less pronounced than it had been ten years earlier. In the years that followed, aboriginal participation in the sex trade receded steadily, as non-aboriginal prostitutes from the United States, eastern Canada, and northern Europe displaced aboriginal prostitutes. Furthermore, the sites of sexual commerce in Victoria shifted. By the 1870s, the sex trade was associated with brothels, not dance houses. Known colloquially as bordellos, bagnios, and sporting houses, brothels were not banished to the edge of town, near the municipal gas works. Rather, brothels in Victoria — in common with brothels in other cities in western Canada and the western United States — were permitted to operate with relative impunity in a few well-defined points close to the centre of the city.[22] One such point was Fisgard Street, in Victoria’s Chinese quarter. Another point was Broad Street, in the city’s business district.

Fisgard Street was, and is still today, the centre of Victoria’s Chinatown. The embryo of Victoria’s Chinatown was established in the early 1860s during the Cariboo gold rush. In 1871, it consisted of about 200 residents.[23] The geographical perimeters of the community expanded and contracted over the next 50 years, but generally it lay within an area bounded by Government Street on the east, Cormorant Street on the south, Store Street and the harbour on the west, and Herald Street on the north.[24] The population of Chinatown increased after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, a project that employed thousands of Chinese labourers. In 1891, the population of Victoria’s Chinatown was about 2,000.[25] Nearly all of the residents were male. Of the female residents, many were concubines or prostitutes. In 1884, Victoria’s superintendent of police, Charles Bloomfield, estimated that there were about 100 female prostitutes in the city’s Chinese quarter.[26] The plight of these women, who were recruited from impoverished rural families in China by Chinese procurers, was a concern for social reform groups in Victoria, including the Women’s Missionary Society of the Methodist Church and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Association (WCTU). In 1887, after a series of sensational reports about the abuse of child concubines, they established the Chinese Girls’ Rescue Home on Herald Street as a refuge for Chinese prostitutes.[27] The Girls’ Rescue Home was later relocated to Cormorant Street. However, because prostitution on Fisgard Street was confined almost exclusively to the Chinese community, it did not receive much attention from authorities. As legal historian John McLaren has noted, “Chinese sexual vice” was not a concern or a priority for the Victoria Police Department.[28] Nor, with a few notable exceptions, did local newspapers devote much attention to the topic. Accordingly, considering the dearth of English-language historical evidence on the extent of prostitution within the Chinese community, the sex trade in Victoria’s Chinatown must remain peripheral to this study.[29] Instead, this paper will focus on sites of sexual commerce elsewhere in Victoria, starting with Broad Street.

Broad Street is only four blocks long. It runs parallel to Victoria’s principal north-south thoroughfares, Government Street and Douglas Street; it connects the city’s principal east-west thoroughfares, Pandora Avenue, Yates Street, View Street, and Fort Street. The Driard Hotel, the most prestigious hotel in the capital city in the Victorian era, anchored one end of the street, while the Pandora Avenue Methodist Church anchored the other end. Victoria City Hall was just around the corner. Tax assessments on properties along Broad Street were among the highest in the city.[30] By the end of the century, Broad Street was home to the Victoria Stock Exchange, the YMCA, and the city’s two daily newspapers. This space in the centre of Victoria’s business district was a nexus of the sex trade.

One of the first references to sexual commerce here occurs in 1861, in a newspaper report about a fire on the roof of a “house of ill-fame on Broad Street.”[31] The report was more concerned with the decrepit state of the brothel’s chimney than with any moral turpitude, since the chimney endangered adjacent properties. The reporter noted approvingly that the (unidentified) proprietor of the brothel had commenced a brick chimney in the aftermath of the fire. Indeed, the indignant wrath that infused contemporary newspaper accounts about dance houses is notably absent in stories about Broad Street brothels. Similarly, the vitriolic language sometimes deployed in descriptions of aboriginal prostitutes is rarely seen in reports about non-native prostitutes. On the contrary, Euro-American sex trade workers are described euphemistically and indulgently as “Cyprians,” “sporting women,” or “women of gay character.” Incidents relating to these women were often characterized by a bemused tone, rather than by expressions of moral outrage. Consider, for example, a newspaper report about an incident involving two angry female prostitutes who stormed into a saloon on Government Street, armed with horsewhips, intent on thrashing a male customer. The incident, which occurred in February 1865, occasioned “considerable amusement” to saloon patrons and readers of the British Colonist. The proprietor of the saloon, “not liking the belligerent appearance of his visitors,” declined their invitation to “take a drink” and “ordered the fair ones to leave in post haste.” According to the Colonist reporter, the “disappointed females” duly left the saloon, but were “evidently much chagrined at not having an opportunity of indulging in the anticipated manual exercise.”[32]

The same tone appears in stories in the decades that followed. Non-native prostitutes and brothel owners are treated indulgently in Victoria’s newspapers, the Colonist and the Daily Times.[33] Newspaper publishers accepted the sex trade as an integral part of city life, although lead writers occasionally complained about the “flagrant” character of the trade. In June 1876, when longtime resident David W. Higgins was proprietor of the Colonist, an editorial in the newspaper remarked: “It is not the existence of the vice that we have found fault with: but it is with the spots it has selected for its abode, which shocks the moral sensibilities and offends the eyes and ears of decent people and lures the young to destruction.”[34] The editorial did not identify specific “spots,” but it was likely a reference to Broad Street. Even so, local police officials were blasé about the Broad Street brothels, as long as the inmates were relatively well-behaved and did not abuse their patrons. Testifying in police court in November 1876, William Bowden, Victoria’s inspector of police, lamented the fact that unsuspecting miners were sometimes robbed of their possessions inside the brothels. Bowden told the court that:

…surveyors and miners coming down from the Cassiar with their seasons earnings frequently come to me, saying “I was on a bit of a spree last night and got enticed into one of those houses on Broad Street, and this morning, when I woke up, I hadn’t got a cent. Now, I haven’t anything to keep me all winter.”

The court heard that it was not sporting to rob guileless miners (“who, perhaps, had not touched liquor for several months and so became easily intoxicated”) in these sporting houses. But there were no objections to the houses per se.[35]

Ten years later, Broad Street was still the centre of the sex trade. According to a police report submitted to Victoria City Council in April 1886, at least seven brothels were operating on Broad Street; each of the brothels accommodated three or four prostitutes. The 1886 report locates sites of sexual commerce on adjacent streets.[36] Brothels were identified on Broughton Street, Johnson Street, Yates Street, View Street, and Trounce Alley. The report also identified the owners of the properties where brothels were operating. Mrs. Margaret Doane, a widow, owned four brothels on Broad Street. Louis Vigelius, a wealthy barber, owned another of the Broad Street brothels. From 1876 to 1897, Vigelius sat on Victoria City Council as the elected representative for Yates Street Ward, the constituency that included Broad Street.[37] Another Broad Street brothel was owned by Simeon Duck, a manufacturer and member of the provincial Legislative Assembly. In 1886, when the police report was compiled, Duck was Minister of Finance in the provincial government.[38] The brothel he owned was located in a wooden structure of undetermined age, near the corner of Broad Street and Johnson Street. A few years later, in 1892, the structure was replaced with a handsome, three-storey brick building. The Duck Block, as the new building was called, accommodated a succession of brothels over the years. Joseph W. Carey, a land surveyor and former mayor of Victoria, owned one of the brothels on Broughton Street. A. A. (Andrew Alfred) Aaronson, a pawnbroker and curio-dealer, and a leading member of Victoria’s Jewish community, owned a brothel on Johnson Street. In his obituary notice, Aaronson was described as “a man of sterling worth and ability, [who] enjoyed the esteem and personal respect of all who knew him.”[39] The same might have been said of the other property owners. They were successful, well-respected citizens who were not stigmatized by their association with the sex trade.

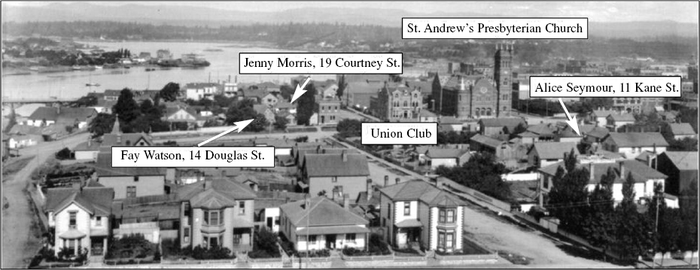

Carey’s property on Broughton Street was managed by a couple of well-known madams, Fay Williams and Della Wentworth. It operated as a brothel for over a dozen years. Other long-running establishments included Fay Watson’s brothel at 14 (now 828) Douglas Street, Jennie Morris’s brothel at 19 (now 621) Courtney Street, and Alice Seymour’s house at No. 11 Kane Street (now 715 Broughton Street).[40] Watson conducted her brothel for over ten years. Morris was in business for 20 years. Seymour operated a brothel from the same site for nearly 25 years. Known as parlour houses, these brothels catered to the so-called carriage trade, that is, their clientele consisted of middle-class and upper-middle-class men.[41] But of course there were also brothels that catered to working-class males. Less fashionable brothels were located on the northern edge of Chinatown, in the industrial sector of the Victoria. The waterfront was crowded with wharves and warehouses for cargo ships and sealing schooners; lumber mills, iron foundries, and residential hotels for working men were situated there. A streetcar line that connected downtown Victoria with the Royal Navy base at Esquimalt, where thousands of sailors were stationed, ran through this part of town. The demographic and economic character of the area was conducive to the sex trade and several brothels were operating by the early 1890s. One of the brothels was located at No. 11 (now 539) Herald Street, in a substantial brick building known as the Hart Block. The building stood on the south side of Herald Street, between Store Street and Government Street. In a manner of speaking, it, too, had connections to the carriage trade. The top floor of the building consisted of a couple of apartments that functioned as brothels. A carriage builder occupied the ground floor of the building.

The area was transformed during the Klondike gold rush (1898–1900) when thousands of men passed through Victoria en route to Dawson City and the goldfields. When the city’s inexpensive hotels and rooming houses were filled to capacity, gold-seekers established temporary encampments on vacant lots near the industrial harbour. The sex trade burgeoned, as scores of prostitutes moved into the area. However, the newcomers did not reside in substantial brick structures like the Hart Block. Rather, the prostitutes who came to this corner of Victoria during the Klondike gold rush lived and worked in hastily-built, one-room wooden cabins known as cribs. The lower end of Chatham Street, located one block north of Herald Street, was crowded with cribs. Years later, Walter Englehardt, a Victoria old-timer, recalled the scene: “You never saw anything like it in your life! All sorts of houses [on Chatham Street], all of them full of girls!”[42]

In addition to brothels and cribs, the sex trade burgeoned in new spaces connected to saloons and hotels during the Klondike gold rush. Jubilee Court, behind the Jubilee Saloon at 49 (now 571) Johnson Street, is a good example. The saloon was built in 1887, but in 1899 a vacant lot behind the saloon was developed as prostitutional space. Concealed behind a high brick wall, Jubilee Court contained a dozen small brick cabins.[43] The cabins were not intended as residences, but simply as places for sexual commerce. Presumably, the bartender would direct patrons to the cabins behind the saloon. Whether sex trade workers were waiting in the cabins, or whether they mingled with customers inside the saloon, is not known. Similarly, details of exchanges between male customers and female prostitutes in the Grand Pacific Hotel are not recorded. Located on the northwest corner of Johnson Street and Store Street, a few hundred meters from the Jubilee Saloon, the Grand Pacific Hotel was erected in 1884. The hotel (now 560 Johnson Street) was also retrofitted for the sex trade sometime in the 1890s. In this case, additional space for sexual commerce was created in the attic of the hotel. Under the high, mansard-style roof, hotel proprietor Lorenzo Reda constructed a number of rooms that faced a small foyer. Access to the foyer and attic rooms was gained by a stairway that led from the main floors of the hotel. Each attic room was fitted with a door and a window. The windows were covered by a screen, which could be opened or closed from within. The physical arrangements suggest that prostitutes waited for customers in these rooms. By opening the window screens, they could be seen from the foyer, thus indicating that they were available for sexual commerce. Some of the rooms were equipped with dumb waiters, to bring food and beverages up from the saloon on the ground floor of the hotel.[44]

Given the plethora of brothels, cribs, cabins, and attic rooms — and the laissez-faire attitudes of the police and the local press — one might think that Victoria was exempt from the Criminal Code of Canada, which imposed severe restrictions on prostitution. But, of course, Victoria was not exempt. The Criminal Code, as amended in 1887, prohibited virtually “every aspect of prostitution except the actual and specific act of commercial exchange for sexual services.”[45] This meant that “keepers of bawdy houses or houses of ill-fame” and “inmates of bawdy houses” (that is, residents of bawdy houses) could be prosecuted under the Criminal Code. In Victoria, “common prostitutes or street-walkers” could also be prosecuted under the city’s Public Morals By-law (1888).

Authorities in Victoria did not tolerate street-walkers. Prostitutes who attempted to conduct business from street corners, side-walks, or back-alleys were speedily arrested and prosecuted. Brothels were tolerated, as long they did not cause disturbances and annoyance to their neighbours. In fact, on several occasions brothel owners were acquitted on charges of running a disorderly house on grounds that the establishments were not in fact disorderly. Inevitably, however, disturbances occurred and neighbours complained. The incumbent of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, on the corner of Broughton Street and Douglas Street, deplored the brothels in the neighbourhood. Trustees of the Methodist Church on the corner of Pandora Street and Broad Street complained when a “house of ill fame” opened next to the church, “a situation that caused the minister’s family and church members a great deal of annoyance.” The rector of the Roman Catholic diocese remonstrated to the mayor about brothels on the north side of View Street, close to the new (1892) St. Andrew’s Cathedral.[46]

When complaints were received, the brothels were raided by police. In the 1870s, brothel keepers had been fined $10, but by the 1880s the fines had increased to $50 for brothel keepers and $25 for brothel prostitutes. “Frequenters” — a term used to describe men who were found in the brothels when they were raided — were liable to a fine of $10. The penalties were levied by magistrates after police officers had raided a brothel. When brothels were raided by the police, the premises were closed; but once the fines had been paid, the brothels re-opened. On some occasions, the whole process — from police raid to court appearance to resumption of business — was completed in a few hours. In September 1892, the Victoria Daily Times reported a police raid on two brothels on View Street, near the Roman Catholic cathedral. “The court sentenced each of the keepers to an hour’s imprisonment and a fine of $50 …. The inmates were likewise sentenced to the same term of imprisonment and a fine of $25.”[47]

Newspaper reports make it clear that the Corporation of the City of Victoria benefited financially from penalties levied on the sex trade. In 1888, a reporter noted that “city coffers were enriched” when May Williams was brought before a police magistrate on a charge of “being the keeper of a bawdy house.” Williams, who ran a brothel on Trounce Alley, off Broad Street, was fined $50. She paid her fine in cash and with aplomb, tossing gold coins onto the table of the court clerk. “The clerk’s table then echoed back the clink of two double eagles and a tenner.”[48] How much the city made is unknown. In some towns in the Pacific Northwest, fines imposed on prostitutes and brothel-keepers constituted an important source of revenue. In Spokane, Washington, “prostitution brought nearly $20,000 a year to the city’s coffers” in the early 1900s. Doubtless, the sex trade was worth at least that much money in Victoria. Moreover, the sex trade was good for the local economy. Figures are not available for Victoria, but business leaders in Spokane estimated that the sex trade was worth “about $80,000 in revenue a year.”[49] The economic importance of the sex trade may help to explain why Victoria merchants, who were doing a brisk trade as outfitters during the Klondike gold rush, urged city council and the police authorities to be as lenient as possible in dealing with sex trade workers on Chatham Street. In terms that recalled debates over dance houses in the early 1860s, Victoria merchants argued that Klondike-bound miners would take their business to Vancouver or Seattle if authorities clamped down on the sex trade. Accordingly, the cribs on Chatham Street were allowed to operate, although crib prostitutes were periodically charged and fined for being “inmates” of a bawdy house.[50]

In the sex trade, fines were the cost of doing business. Those expenses were usually borne by the brothel-keepers and resident sex-trade workers. But there were other expenses, notably rent. Most brothel-operators had to pay some kind of rent to the persons who owned the building where they operated. People who owned brothels did not boast of the fact, but we can identify them from property tax assessment rolls. Tax assessment rolls for 1891 show many of the same names listed on the police report of 1886. But the rolls indicate some newcomers among the ranks of taxpayers who owned properties connected with the sex trade. In 1891, the ranks included Amor de Cosmos, the former editor of the Colonist newspaper, who had railed against dance houses 30 years before.[51] The picture is much the same when we look at the tax rolls for 1901. The people who owned brothels and cribs in Victoria came from a wide but respectable spectrum of society. Property owners included a carriage builder, a saw mill owner, a stable-keeper, a widow, a spinster, and an investment agent. It is unlikely that they were unaware of the kind of commerce conducted on their properties.[52]

A few brothel keepers owned their own premises. Alice Seymour owned her premises on Kane Street. Therese Bernstein, a long-time madam, owned the building she operated as a brothel at 19 Courtney Street. Stella Carroll, a flamboyant madam who came to Victoria from San Francisco in 1899, initially rented two floors in the Duck Block on Broad Street, but later purchased her own property on Herald Street.[53] So, in addition to the fines that Carroll and her colleagues paid at the Police Magistrate’s Court from time to time, they paid property taxes and thus made further contributions to the city’s coffers.

The late 1890s and early 1900s marked the apogee of the sex trade in Victoria. According to John Langley, Victoria’s chief of police, there were about 280 “known prostitutes” in the city in the year 1900.[54] Whether the “known prostitutes” were all working is not clear from his statement, but the statistic he offered is striking. The population of Victoria was just under 21,000 in 1901.[55] Had sex trade workers been enumerated as a distinct occupational category on the 1901 census, they would, if we use Chief Langley’s figures, constitute one of the largest occupational groups among young, white women in the city.[56] Without question, sex trade workers comprised a large sector in Victoria’s invisible economy, although they themselves were by no means invisible in the community. While sex trade workers were not permitted to solicit on the streets, they were not confined to brothels or cribs when they were not working. Like other residents of the city, they interacted with public space and with commercial and recreational places. Some of the women were intentionally conspicuous in their dress and deportment. They wore brightly-coloured dresses and extravagant hats, and carried on in a flamboyant manner. And in this manner, a kind of sexualized space was created as they moved about the city.

Often, brothel operators and prostitutes hired open air carriages and drove around the main streets of the city in an exercise called “taking the air.” Frequently, they strolled to Beacon Hill Park, the city’s main recreation ground, or drove their own carriages to the park. They attended Victoria’s theatres and music halls, which were conveniently located close to Broad Street, and they perambulated along Government Street, between Fort Street and Yates Street. Generally, they were able to conduct themselves in public places without hindrance, although some observers were offended by their presence. In 1889, Arthur Richards, a Victoria lawyer who served as a police magistrate, complained that “women composing the demi-monde” occupied the best seats in the theatre. He was also offended by their manners in the city’s main park. “At Beacon Hill,” he fumed, “they were always to be found flaunting gilded vice in the face of respectability; while on the drives they dashed along in their carriages and smiled upon the respectable women whom they compelled, in a manner, to associate with them.”[57] From Richards’ perspective, sex trade workers were intruding in respectable public space. Other residents may have shared his point of view, but if they did, they kept their opinions to themselves, because we see very few censorious comments about prostitutes in public places in Victoria newspapers in the 1890s.

That being said, the liberal — or, as contemporary critics said, permissive — attitudes of the high Victorian era, the Gay Nineties as this historical period used to be called, were replaced by less tolerant attitudes in the Edwardian years. Laissez-faire gave way to restrictive policies on the part of local authorities. A spectacular fire, which destroyed the city’s largest red-light district, also affected the sex trade significantly. All of these factors unfolded in a social and political environment that was increasingly dominated by the social purity crusades of the era.

It is difficult to determine precisely when attitudes began to change, but changes were in the air and on the minds of civic reformers in December 1898. In that month, a group calling itself the Committee of Fifty was convened at a large public meeting held in Victoria’s City Hall. Members of the Committee had a wide range of objectives, including municipal tax reforms and the removal of the Songhees Indian village from the western side of the harbour. Social and moral issues were also on the agenda. Committee chairman Noah Shakespeare, a former mayor and MP for Victoria, demanded that local authorities be more aggressive in enforcing laws relating to prostitution. Shakespeare recognized that it would be difficult to eradicate prostitution, since it had flourished for so long in the city; however, he said, “the evil [is] getting beyond bounds and it was time it was checked.” While a few committee members endorsed his view, others demurred. One member of the Committee of Fifty, recognizing the importance of the sex trade and sojourning Klondike miners to the local economy, urged his colleagues “not to go to extremes” in enforcing laws against prostitution.[58]

Once the Klondike rush was over, businessmen who took a lenient attitude towards the sex trade found themselves in an increasingly untenable position. From about 1906, the social purity crusade, already felt in many Canadian and American cities, gained momentum in Victoria.[59] Organizations such as the WCTU, which had previously focussed on Chinese prostitutes, turned their attention to the mainstream sex trade. An alliance of the WCTU, the Local Council of Women, and the Salvation Army organized a series of meetings to denounce the brothels and sent a succession of petitions to Victoria City Council, demanding restrictive measures against the sex trade. With members of the local Purity League, they deliberately disturbed and intruded into prostitutional space, by holding vigils outside Herald Street brothels and haranguing customers.[60]

The economy of Victoria was undergoing a major change at this time. The sealing industry, which had employed hundreds of men who lived in residential hotels near the waterfront in Victoria, was shut down by an international treaty.[61] The Royal Navy base at nearby Esquimalt closed in 1905, and with the closure several thousand bluejackets, who used to take leave and spend their money in Victoria, were lost to the local economy. At the same time, Victoria’s manufacturing industries were declining in the face of vigorous economic growth in Vancouver. In short, the economic base that had sustained the sex trade was thinner and more tenuous than it had been in the past. Moreover, and of no little importance, this was a period when civic officials and members of the local chamber of commerce were making a concerted effort to promote the city of Victoria as a genteel haven for retirees and an attractive destination for tourists.[62] The construction and opening of the landmark Empress Hotel in 1908 was part of a larger initiative to promote Victoria as a tourist destination. In the newly invented city of gardens, sex trade workers were regarded as nettles.[63]

A conflagration also had a devastating impact on the sex trade. On a hot day in July 1907, a fire got out of control in a blacksmith’s shop on Store Street. The fire spread rapidly to adjacent properties and before it was extinguished it destroyed all of the buildings on the lower (western) part of Chatham Street. In a front page story, the Victoria Daily Colonist reported: “Lower Chatham is occupied exclusively by cribs and there were many painful scenes among the terror stricken denizens. Women in scanty attire fled into the streets imploring aid, which was cheerfully rendered.”[64] Fortunately, there were no deaths or injuries in the fire, but the sex trade was never the same.

In the wake of the 1907 fire, the Victoria Police Commission, acting on instructions from Victoria City Council and moral reform groups, established a “restricted district” where brothels would be permitted. This marked a change in local policy and a new way of defining prostitutional space. Previously, prostitutional space had been defined by function and such spaces existed in different parts of the city. Subsequently, prostitutional space was defined by regulations. Regulators, who had simply gazed at sex trade workers in the past, were now expected to discipline them by enforcing policies intended to curtail sexual commerce. At this time, many cities in western Canada were establishing similar zones, so Victoria’s policy was not innovative or unusual.[65] However, the restricted zone in Victoria was proportionally smaller than other major cities. Certainly, it was much smaller than it had been prior to 1907. It was limited to the western end of Herald Street and Chatham Street. Brothels were allowed to operate there, provided they were not conspicuous.[66] Conspicuous was a relative term, but gone were the days when brothels announced their presence by posting oversized street address numbers on their front doors and installing red blinds in their front windows.[67] Further restrictions were imposed in January 1910, when Herald Street was closed to the sex trade. Thereafter, officially-sanctioned prostitutional space was limited to the western end of Chatham Street.[68]

The brothels on Broad Street closed following the imposition of new regulations in 1907. At this time, property values in this part of the city were increasing and several former brothel sites were redeveloped profitably for legitimate commercial purposes. Different economic pressures affected the sexual marketplace at the north end of town. It was rumoured that brothel operators on Herald Street and Chatham Street were compelled to pay protection money to corrupt police officers in order to stay in business. The rumours prompted a government enquiry in March 1910 under the direction of provincial court judge Peter Lampman. Lampman found no evidence of police corruption or connivance on the part of civilian police commissioners. However, the enquiry revealed that prostitutional space in this part of Victoria was controlled by a relatively small number of property owners, and that the space had become very expensive for brothel operators. The enquiry records show that many of the properties within the restricted zone were owned by trading companies, such as the Hip Yick Company, controlled by Chinese merchants in Victoria. Immediately after the fire of 1907, Chinese investors commenced buying up properties on Chatham Street and erecting small brick cottages, which were then rented as brothels. Building lots on lower Chatham Street were also acquired by a local property developer, Lorenzo Quagliotti, and his wife Petronilla Quagliotti. They leased some of their properties to Lorenzo Reda, the proprietor of the Grand Pacific Hotel. Reda, it may be recalled, had installed cribs in the attic of his hotel during the Klondike gold rush. This time, Reda erected five cottages on Chatham Street, which he sub-let as brothels.

Because the restricted zone was geographically and morally circumscribed, brothel operators were compelled to pay exorbitant rents. One brothel keeper reported that she paid more than $150 a month to rent a house from the Hip Yick Company; another madam paid $200 a month in rent for her property. To put these prices in context, three-bedroom bungalows in respectable, residential neighbourhoods of Victoria rented for $150 a year in 1910. Before the sex trade industry collapsed, the new regulations provided a bonanza to landlords. The Lampman enquiry heard that Lorenzo Reda earned $1,000 a month in rent from the cottages he had erected, of which he paid $350 per month to Mr. and Mrs. Quagilotti.[69] In addition to unprecedented operating costs, sex trade workers had to endure harassment from moral reformers. Petty regulations aimed at prostitutes were vexatious, too. For example, theatres in Victoria instituted a policy of segregating “public women,” as sex trade workers were sometimes called, from other patrons. Historical references to the policy are imprecise, but female prostitutes were apparently relegated to blocks of seats in theatre balconies. It is not clear when the policy was implemented and whether it was initiated by theatre managers at the behest of local authorities, but Police Chief Langley referred to it approvingly in 1910 when he testified at the Lampman enquiry.[70] As it happened, the policy was resisted by some sex trade workers. Women relegated to the restricted seats in the balcony would whistle and shout down to men they recognized in the respectable dress circle of the theatre.[71] In any event, the policy of segregating sex trade workers in Victoria theatres is an interesting example of how a shift in social attitudes could create new moral geographies in spaces that had been unbounded previously.

Succumbing to social, political and economic pressures, many brothel keepers — including those who operated long-established parlour houses — closed their businesses and left Victoria. Fay Watson closed her brothel on Douglas Street in 1909. Jennie Morris closed her parlour house on Courtney Street a year later. Both women operated their brothels in rented facilities and may have buckled under increased operating costs. As noted earlier, property prices were rising dramatically in Victoria at this time and some brothel operators may have taken advantage of the soaring market, which may explain why Alice Seymour, who owned her brothel on Broughton Street (formerly Kane Street), closed it in 1912 and retired to California. But the censorious climate engendered by the social purity campaign was also a factor. Having been hounded out of Herald Street, Stella Carroll opened a brothel on the outskirts of the city. She was not immune from prosecution there and in 1913, after a long-running battle with authorities, she quit Victoria and returned to San Francisco.[72]

At the onset of World War I, the sex trade in Victoria was, to use a cliché, but a shadow of its former self. The change can be seen in statistics compiled by the Victoria police department. In 1899, near the apogee of the sex trade, just seven charges were laid against brothel operators — despite the fact that dozens of brothels were doing business at the time. In 1908, as the crackdown on the sex trade got into full swing, the police laid nearly 50 charges for offences relating to prostitution and public morals. In 1914, when the sex trade had largely been subdued, only six charges were brought to court. “The morals of the city,” Victoria’s mayor, Alfred J. Morley, boasted in his annual report for 1913, had attained a “high standard and everything possible has been done to prevent questionable characters from locating in the city.”[73] As a result of this policy, sex trade workers were subjected to unprecedented surveillance. When they were arrested they were photographed, even before they were brought to trial. Their photographs, which inter alia provide a fascinating record of the sex trade, were kept on file. Copies of the photographs were circulated to police departments in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, to assist officials in those cities in their campaigns against vice and immorality. Moreover, women from those cities who were suspected of being prostitutes were made to feel unwelcome in Victoria. Referring to sex trade workers in his report for 1915, the police department’s chief detective remarked, “[that] class of offender did not give as much trouble as formerly.” He reported that his officers had interviewed over 80 suspected female prostitutes that year and had “advised” them to leave Victoria. He claimed that “in nearly all cases” the women took the advice and left town.[74]

III

Prostitutional space was social space and, as Doreen Massey has observed, “[s]ocial space is something we construct and which others construct about us.”[75] For most of the nineteenth century, this social space in Victoria was packed with economic values. That is, sites of sexual commerce were tolerated by local authorities because the sex trade was important to the local economy. Evidence of this is seen in the colonial era, during the Cariboo gold rush, in debates about allowing dance houses to operate in the city. Economic interests were at play during the Klondike gold rush, when the business community urged municipal authorities to go easy on the brothels on Herald Street and the cribs on Chatham Street. On other occasions, evidence exists even during times when the city was not inundated with transient gold seekers. In December 1890, the mayor of Victoria, John Grant, rebuked a delegation of clergymen who had come before council to complain about the proliferation of brothels in the city. The meeting was open to members of the public. Far from sympathizing with the delegates, Grant charged that they were giving the city “a black eye” by representing Victoria as a “bad” and “immoral place.” He accused the clergymen of being intolerant and blamed them for discouraging investment in the city. Their allegations about immorality, Grant said, “have been detrimental to the best interests of the city.”[76] When the delegates protested, they were booed and hissed by spectators in the public gallery.[77]

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the sex trade in Victoria may also have owed its standing to a widely held view that prostitution was a necessary evil. In this construction, the “activities of prostitutes were seen to preserve the moral purity and integrity of ‘good’ women by providing an outlet for men’s baser desires. Given its necessary function, prostitution was to be tolerated, isolated, and regulated rather than eradicated altogether.”[78] A long-time medical practitioner, Dr. J. S. Helmcken, expressed this view at a meeting of the Victoria Police Commission in 1898. He was speaking against measures that would curtail prostitution around Herald Street and Chatham Street. His remarks were reported in the press as follows: “There is a necessity for such women [prostitutes] and he for one would rather see them here [in Victoria] than see the lunatic asylums crowded with young men.” Helmcken’s audience would have understood his meaning: If young men had access to prostitutes, they would not resort to masturbation, a practice which could lead to insanity.[79] Further, “He as a medical man could say that if those houses [brothels] were closed, there would be trouble for the young girls of the city.” Again, the commissioners would know what he meant: If prostitutes were not available in a seaport like Victoria, respectable females would be accosted by miners, sailors and other marauding males who comprised the “large floating population” of the city. Dr. Helmcken advised that it was better to “relax the law” against prostitution and “safer to have the bawdy houses, properly restricted.” Arguments like these were advanced to justify the allocation of prostitutional space. Moreover, when these patriarchal opinions were coupled with economic imperatives, such as those expressed by Mayor Grant, the rationale to produce and preserve prostitutional space in the city was compelling. Accordingly, space was duly allocated in Victoria for sexual commerce.

In Foucauldian terms, the spaces were “places of tolerance” where the state allowed “pleasures that [were] unspoken” to be rendered into “the order of things that are counted.”[80] But in the Edwardian years, the state, in its municipal genus, became less tolerant of these kinds of activities. The state became less tolerant when public opinion changed. Public attitudes towards the sex trade were altered to some extent by women’s organizations (notably the WCTU), religious organizations, and civic reformers who campaigned under the banner of social purity. Their crusade was effective and they were understandably pleased to see a marked decline in sexual commerce. Thus, in 1914 the British Columbia conference of the Methodist Church was moved to “place on record its gratification” that the campaign to close “houses of ill-fame” and abolish “segregated districts of social vice” in Victoria and other cities in the province had been successful.[81] But the social purity crusaders cannot claim all of the credit. As John McClaren and others have noted, the curtailment of the sex trade was part of a larger social phenomenon that gained momentum in the initial decades of the twentieth century. Along with moral reform, the phenomenon involved increased social control and governmentality. In British Columbia:[82]

…state authorities increasingly turned to the cultural realm in their struggles to recreate and discipline the populace. More and more, governance, law, authority, and rule became discursive activities, mediated in public and private life through semi-autonomous institutions like education, religion, social work, the academy, and the press. In the process, the state entered into new relations with civil society. The science and art of governmentality became a far more complex phenomenon than previously envisioned …. These new thought forms, strategies, and methodologies were aimed not only at repressing deviant outsiders, but also at instilling new modes of logic and conduct among the citizenry at large.

The tendencies of moral reform, social control, and governmentality, which have interested McLaren and others, were characteristics of twentieth century progressivism. In British Columbia, and elsewhere in English-speaking North America, progressivism was expressed in a wide range of social initiatives, which took the form of statutes and by-laws to combat a perceived increase in juvenile delinquency and promote public health.[83] The social purity campaign against the sex trade was, consequently, part of a larger initiative to improve social efficiency. In addition, other factors diminished and to some degree undermined the unbridled sex trade of the high Victorian era. Paradoxically, in light of the ostensible objectives of social purity, one of the factors was a greater tolerance of premarital sex. Other factors involved the advent of companionable marriages, the acceptance of consensual sexual intercourse within marriage, the increased use of contraceptives, and a shift towards earlier marriages. As Timothy Gilfoyle noted in his study of prostitution and the commercialization of sex in New York:

The ideals of emotional warmth, amicability, and affection replaced rigid Victorian authority and responsibility as the defining qualities of the American family. Equally significant, sex was increasingly seen as a legitimate physical function, a crucial part of married life, and a basic expression of love within marriage. The increasing acceptance and availability of artificial birth control contributed to this change. Heterosexuality was transformed, but within older, monogamous traditions restricting sex to marriage. Sexual intercourse was a positive good, the acme of love, and, most important, the hallmark of equality in marriage.

Gilfoyle argues that a combination of attitudinal changes, redefinitions of intimacy and marriage, and younger (and companionable) marriages undermined the late Victorian brothel and public prostitution. He also points to the fact that, as cities grew and urban development was intensified, spaces that had been given over to the sex trade became increasingly valuable for commercial or industrial development.[84] All of these forces were significant in undermining the demi-monde in Victoria.

IV

As a metropolitan centre, Victoria reached its zenith in the mid-1890s. The “Queen City,” as local boosters liked to call it, was extolled in many promotional books and brochures.[85] Typically, these publications included pictures of handsome streets and buildings in the city centre. The image and physical space of Victoria was conveyed in other ways, including panoramic photographs which were sold as prints and post-cards. One such photograph was created in 1895 and frequently reprinted during the period. In this panoramic view, taken from a vantage point near the Anglican cathedral on Church Hill, the photographer has aimed his camera at two impressive buildings standing close to each other on Douglas Street, one of Victoria’s main thoroughfares. The photograph shows the Union Club of British Columbia (1885), an exclusive club for gentlemen and social headquarters of the province’s patriarchy, and St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church (1890), spiritual home of the province’s enterprising Scottish community, some of whom were members of the Union Club. The photograph radiates high Victorian respectability. But looked at closely and in the right spots, brothels are visible. Some of the brothels are situated very close to the church and the patrician club house.[86] In this photograph Fay Watson’s house on Douglas Street, Jenny Morris’ house on Courtney Street, and Alice Seymour’s house on Kane Street are visible. Structurally, the houses are unremarkable; they are modest, ordinary-looking residences. But this panoramic view of Victoria becomes much more interesting when the wider moral and cultural geography of the landscape is seen, giving a better appreciation of the functional character of the space the buildings occupy. At this point, a Victorian city is visualized in new ways, with spaces that are invisible and yet discernible — spaces that Foucault called heterotopias.

Heterotopian space exists beside and in contrast to utopian space, which represents society’s idealized image of itself. “There also exist in real and effective spaces which are outlined in the very institution of society, but which constitute a sort of counter-arrangement of effectively organized utopia … a sort of place that lies outside all places and yet is actually localizable,” Foucault said. “In contrast to utopias, these places, which are absolutely other with respect to the arrangements that they reflect and of which they speak might be described as heterotopias.”[87] Foucault posited several principles that governed heterotopias, one of which involved the juxtaposition of space: “The heterotopia has the power of juxtaposing in a single real place different spaces and locations that are incompatible with each other.”[88] The brothels that stood on Broughton Street, Douglas Street, and Courtney Street, close to St. Andrew’s Church and the Union Club, existed in heterotopian space. These sites of sexual commerce call to mind Gillian Rose’s concept of “paradoxical space.” According to Rose, paradoxical space is a geographical element that has “multiple and contradictory” meanings. It is “a different kind of space through which difference is tolerated rather than erased.”[89] The paradoxical geography that Rose describes is surely an apt metaphor for the parlour houses that Alice Seymour and other madams operated. Sited on respectable streets and doing business for decades, they were places where difference was tolerated. In those sites of sexual commerce, women occupied both the centre and the margin of social space. The less fashionable brothels on Herald Street are also heterotopian, inasmuch as they represent physical and functional space that is both obvious and hidden. “Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that isolates them and makes them penetrable at one and the same time.” To illustrate his point, Foucault evoked an image of American motels. Prominently sited on highways where everyone can see them, motels provide accommodation for travellers; but they are also places were lovers meet, “where illicit sex is totally protected and totally concealed at one and the same time.” Foucault offered brothels as an “extreme example” of a heterotopia.[90] Certainly, the brothels discussed in this study, and the other sites of sexual commerce considered here, manifest the characteristics of a Foucauldian heterotopia.

V

This paper began by alluding to some ideas of Foucault’s contemporary, the philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre who wrote a seminal work on the production of social space. In modern Western societies, Lefebvre argued, urban space is produced by the imperatives of capitalism, dominated by the bourgeoisie, and regulated by the state. Prostitutional space in Victoria was determined and characterized by the same factors. Sexual commerce was a significant part of Victoria’s economy and the men and women who owned the brothels, cribs, and cabins that constituted the physical form of the sexual marketplace must be counted among the city’s bourgeoisie. On the matter of regulation, female prostitutes in the colonial outpost of Victoria were never regulated as closely as they were in some parts of the British Empire; and while Victoria exhibited many characteristics of a British naval or garrison settlement, sex trade workers in Victoria were never subjected to the contagious disease ordinances that were common in many British colonial possessions.[91] Nevertheless, the sex trade in Victoria was never actually unregulated by the state. Regulations took different forms, such as licenses issued to dance halls in the colonial era, police raids on bawdy houses in the late Victorian era, and ultimately geographical restrictions in the Edwardian era. The fact that brothels and cribs were permitted to operate in different parts of the city was a tacit form of regulation. As Philippa Levine observed in her study of prostitution in the British Empire: “For the brothel to be properly controlled, it needed to be visible, yet its business was something officials always hoped they could at least partially conceal.”[92]

When social purity advocates gained influence on Victoria’s municipal council and the local chamber of commerce, and when Victoria was re-invented as a city of gardens and ersatz English gentility, sites of sexual commerce became increasingly concealed. Prostitutional space produced during the nineteenth century was redeveloped in the twentieth century and in the twenty-first century it was almost forgotten. This study is a tentative step in recovering and mapping that space, with a view of reassessing the social history and cultural geography of Victoria. Similar studies might be undertaken in other Canadian cities with a view of re-examining local economies and addressing larger questions relating to sexuality. But, as Lefebvre reminds us, “spaces are strange: [they are] homogeneous, rationalized and as such constraining; yet at the same time utterly dislocated.”[93] The spaces we see on historical maps and photographs appear to be transparent and self-evident, but from a theoretical perspective they are exceedingly problematic. As Lefebvre explained, “this transparency is deceptive, and everything is concealed: space is illusory and the secret of the illusion lies in the transparency itself.”[94] Because of the illusory nature of social space, delineating moral geographies on historical landscapes is a challenging exercise. The reward of the exercise is a better understanding of social attitudes and activities that have received relatively little attention in scholarly studies, and a glimpse of how liminal spaces functioned in a frontier colonial community such as Victoria, British Columbia. The reward is also a new perspective on this particular community. Although Victoria has been the subject of many historical studies, the city invites a closer and more critical scrutiny. Evidence presented in this study suggests that sexual commerce, not Suttons’ English garden seed catalogues, accounted for the character of the Queen City in its formative years.

Figure

Appendices

Biographical Note / Note biographique

Patrick Dunae

A former chair of the Department of History at Vancouver Island University, Patrick Dunae is an adjunct associate professor in History at the University of Victoria. He is working on an historical geographical information system [GIS] of Victoria.

Ancien directeur du Département d’histoire de la Vancouver Island University, Patrick Dunae est professeur agrégé adjoint d’histoire à l’Université de Victoria. Il élabore actuellement un système d’information géographique (GIS) de nature historique sur Victoria.

Notes

-

[1]

British Colonist (23 December 1861).

-

[2]

Mathew Macfie, Vancouver Island and British Columbia. Their History, Resources and Prospects (London: Longman, Roberts & Green, 1865), 470–1; British Colonist (25 December 1861).

-

[3]

John Pickles, “Social and Cultural Cartographies and the Spatial Turn in Social Theory,” Journal of Historical Geography 25, no. 1 (1999): 93.

-

[4]

I have borrowed the term “placing dots on a map” from David Bell and Gill Valentine who used it to describe the work of an earlier generation of geographers who, in their view, were not sufficiently critical, analytical, or imaginative. David Bell and Gill Valentine, eds., Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities (London: Routledge, 1995), 4.

-

[5]

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1991), 23.

-

[6]

Alison Blunt and Gillian Rose, eds., Writing Women and Space. Colonial and Postcolonial Geographies (New York and London: Guilford Press, 1994), 45–6.

-

[7]

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality. Volume I: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 116.

-

[8]

Gillian Rose, Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 154; Michel Foucault, “Other spaces: The principles of heterotopia,” Lotus International 48 (1998): 9–17.

-

[9]

On the economic development of Victoria, see J.M.S. Careless, “The Business Community in the Early Development of Victoria, British Columbia,” in Historical Essays on British on British Columbia, eds. J. Friesen and H.K. Ralston (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1976); Charles N. Forward, “The Evolution of Victoria’s Functional Character,” in Town and City: Aspects of Western Canadian Urban Development, ed. Alan F.J. Artibise (Regina, Sask.: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina Press, 1981); and Peter A. Baskerville, Beyond the Island: An Illustrated History of Victoria (Burlington, Ont.: Windsor Publications, 1986).

-

[10]

British Colonist (22 November 1864).

-

[11]

Ibid. (23 December 1861).

-

[12]

Ibid. (28 November 1862 and 1 December 1862).

-

[13]

Ibid. (23 December 1861 and 25 December 1861).

-

[14]

Jean Barman, “Taming Aboriginal Sexuality: Gender, Power, and Race in British Columbia, 1850–1900,” BC Studies nos. 115/116 (1997–1998): 243–4; Adele Perry, On the Edge of Empire. Gender, Race, and the Making of British Columbia, 1849–1871 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 110–23. The topic is also explored by Adele Perry in “Metropolitan Knowledge, Colonial Practice, and Indigenous Womanhood: Missions in Nineteenth-Century British Columbia,” in Contact Zones. Aboriginal and Settler Women in Canada’s Colonial Past, eds. Katie Pickles and Myra Rutherdale (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005), 109–30.

-

[15]

Jean Barman, “Aboriginal Women on the Streets of Victoria,” in Contact Zones, 217.

-

[16]

John Lutz, “Gender and Work in Lekwammen Families, 1843–1970,” in Gendered Pasts: Historical Essays in Femininity and Masculinity in Canada, eds. Kathryn McPherson, Cecilia Morgan, and Nancy M. Forestell (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1999), 90–1; Barman, “Aboriginal Women on the Streets of Victoria,” citing Carol Ann Cooper, “‘To Be Free on Our Lands’: Coast Tsimshian and Nisga’a Societies in Historical Perspective, 1820–1900” (Ph.D. diss., University of Waterloo, 1993), 184.

-

[17]

Macfie, Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 470–1.

-

[18]

Baskerville, Beyond the Island, 39; James E. Hendrickson, ed., Journals of the Colonial Legislatures of the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1851-1871 (Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1980), I, 198.

-

[19]

Vancouver Times (4 April 1866).

-

[20]

Jay Nelson, “‘A Strange Revolution in the Manners of the Country’: Aboriginal-Settler Intermarriage in Nineteenth Century British Columbia,” in Regulating Lives: Historical Essays on the State, Society, the Individual, and the Law, eds. John McLaren, Robert Menzies, and Dorothy E. Chunn (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2002). Nelson notes that in the closing decades of the nineteenth century “aboriginal women were increasingly deterred from relationships with white men by policies implemented by a shifting alliance of missionaries, local Aboriginal men, and Indian agents,” 46.

-

[21]

Grant Keddie, Songhees Pictorial: A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790–1912 (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 2003); Renisa Mawani, “Legal geographies of Aboriginal segregation in British Columbia: the making and unmaking of the Songhees reserve, 1850–1911,” in Isolation. Places and practices of exclusion, eds. Carolyn Strange and Alison Basher (London: Routledge, 2003), 173–90.

-

[22]

The literature on prostitution in Western Canada is extensive. Useful works include James H. Gray, Red Lights on the Prairies (Saskatoon, Sask.: Fifth House, 1995); Judy Bedford, “Prostitution in Calgary, 1905–1914,” Alberta History, 29, no. 2 (Spring 1981): 1–11; Deborah Nilson, “The Social Evil: Prostitution in Vancouver 1900–1920,” in In Her Own Right, eds. Barbara Latham and Cathy Kess (Victoria, B.C.: Camosun College, 1980), 205–28; and Charleen P. Smith, “Boomtown Brothels in the Kootenays, 1895–1905,” in People and Place. Historical Influences on Legal Culture, eds. Jonathan Swainger and Constance B. Backhouse (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2003), 120–52. Useful studies relating to the American West include, Joel Best, Controlling Vice: Regulating Brothel Prostitution in St. Paul, 1865–1883 (Columbus: Ohio University Press, 1986); Anne M. Butler, Daughters of Joy, Sisters of Misery. Prostitutes in the American West, 1865–1890 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1985); Jacqueline Baker Barnhart, The Fair But Frail. Prostitution in San Francisco 1849–1900 (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1986); Marion S. Goldman, Gold Diggers & Silver Miners. Prostitution and Social Life on the Comstock Lode (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981); and Jan MacKell, Brothels, Bordellos, & Bad Girls. Prostitution in Colorado, 1860–1930 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004).

-

[23]

Canada. Sessional Papers, 1872. Vol. 6, no. 10, “British Columbia,” 22. The main street in Victoria’s Chinese quarter is named after a Royal Navy vessel, H.M.S. Fisguard. In the nineteenth century it was spelled Fisguard. The modern spelling is Fisgard.

-

[24]

David Chuen Yan Lai, “Socio-Economic Structures and Viability of Chinatown,” in Residential and Neighbourhood Studies in Victoria, ed. Charles N. Forward (Victoria, B.C.: University of Victoria, 1973), 102–3.

-

[25]

Census of Canada, 1881, Victoria City Johnson Street Ward (census district 4-B-3). Official census records for Victoria are available at viHistory at <http://www.vihistory.ca>. Viewed on 1 June 2008.

-

[26]

Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration (Ottawa: Printed by Order of the Commission, 1885), Evidence of Police Superintendent Charles T. Bloomfield, 12 August 1884, 48.

-

[27]

David Chueyan Lai, Chinatowns. Towns within Cities in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1986), 205–6.

-

[28]

John McLaren, “Race and the Criminal Justice System in British Columbia, 1892–1920: Constructing Chinese Crimes,” in Essays in the History of Canadian Law, Volume III, In Honour of R. C. B. Risk, eds. G. Blaine Baker and Jim Phillips (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 1999), 422.

-

[29]

Prostitution in Victoria’s Chinatown is discussed in Tamara Adilman, “A Preliminary Sketch of Chinese Women and Work in British Columbia, 1858–1950,” in Not Just Pin Money, Selected Essays on Women’s Work in British Columbia, ed. Barbara Latham (Victoria, B.C.: Camosun College, 1984); 195–196; Anthony Chan, Gold Mountain (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1982), 80–5; and Lai, Chinatowns. Towns within Cities in Canada, 95–196. Prostitution in Victoria’s Chinese quarter is also mentioned in the 1902 Royal Commission, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration (Ottawa: S.E. Dawson, 1902), 22, 38–41.

-

[30]

P.D. Floyd, “The Human Geography of Southeastern Vancouver Island, 1842–1891,” (M.A. thesis, University of Victoria, 1969), 172.

-

[31]

British Colonist (23 October 1861).

-

[32]

Ibid. (10 February 1865).

-

[33]

The nomenclature of Victoria newspapers can be confusing. The British Colonist (1858) became the Daily British Colonist (1873) and, finally, the Daily Colonist (1887). Amor de Cosmos founded the paper, but David W. Higgins was proprietor of the paper from 1862 to 1886. The Victoria Daily Times was launched in 1884. The two papers merged to become the Victoria Times-Colonist in 1980.

-

[34]

Daily British Colonist (21 June 1876).

-

[35]

Ibid. (7 November 1876).

-

[36]

City of Victoria Archives, Victoria Police Committee, Report of Charles Bloomfield, Chief of Police, to D.W. Higgins, chairman, 7 April 1886.

-

[37]

Vigelius, the proprietor of the St. Nicholas Hair Dressing Salon, was indeed a wealthy barber. In 1885 he commissioned John Teague, one of Victoria’s most eminent architects, to design a house for him in a very fashionable neighbourhood. Victoria Daily Colonist (19 April 1889).

-

[38]

Annual Report of the Department of the Provincial Secretary, 1973 (Victoria: 1974), Appendix A, v54–v57.

-

[39]

Victoria Daily Colonist (8 January 1912).

-

[40]

In 1907, the streets of Victoria were re-numbered according to the Philadelphia System. Some of the streets were renamed. Kane Street became a continuation of Broughton Street.

-

[41]

See C.L. Hansen-Brett, “Ladies in Scarlet: An Historical Overview of Prostitution in Victoria, British Columbia, 1870–1939,” British Columbia Historical News, 19 (1986): 21–6.

-

[42]

British Columbia Archives (BAC), Sound recording, T3247:0001, Walter Englehardt’s reminiscences in “A Child’s View of Old Victoria,” interview with Imbert Orchard, CBC, 1962. Excerpts published in A Victorian Tapestry. Impressions of Life in Victoria, B.C., 1880–1914, ed. Janet Cauthers (Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1978), 14–15.

-

[43]

Victoria Daily Colonist (6 June 1899). Jubilee Court and its cabins can be seen on fire insurance plans of the period. The cabins were demolished in the 1970s.

-

[44]

I am grateful to Victoria historian John Adams for alerting me to the attic rooms of the former Grand Pacific Hotel and to the current building managers for allowing me to inspect and photograph the space.

-

[45]

See Constance B. Backhouse, “Nineteenth-Century Canadian Prostitution Law. Reflection of a Discriminatory Society,” Social History / Histoire sociale, 18 (November 1985): 387–423. See also Backhouse, Petticoats and Prejudice: Women and Law in Nineteenth Century Canada (Toronto: Women’s Press, published for the Osgoode Society, 1991), chap. 8; and John McLaren, “Chasing the Social Evil: the Evolution of Canada’s Prostitution Laws 1867–1917,” Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 1 (1986): 125–66.

-

[46]

Victoria Daily Colonist (18 December 1890); United Church of Canada, British Columbia Conference Archives, “History of the Metropolitan Church, Victoria, B.C., by Mrs. Thomas H. Johns,” typescript, n. d., 83–5; Vincent J. McNally, The Lord’s Distant Vineyard: A History of the Oblates and the Catholic Community in British Columbia (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2000), 225.

-

[47]

Victoria Daily Times (15 September 1892), emphasis added.

-

[48]

Ibid. (8 December 1888).

-

[49]

Noel Rettman, “Business, Government, and Prostitution in Spokane, Washington, 1889–1910,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 89, no 2 (Spring 1998): 75–82. See also Paula Petrick, “Capitalists with Rooms: Prostitution in Helena, Montana, 1865–1900,” Montana, the Magazine of Western History, 31, no. 2, (1982). Petrick notes that prostitution was “big business” in Helena. In 1890, eight of Helena’s leading madams owned property assessed at over $100,000 and contributed “nearly $1,000 to the city’s coffers in personal and property tax. Only a few of Helena’s most successful entrepreneurs and the Pacific Northern Pacific Railroad paid more tax than the demimonde,” 38.

-

[50]

Cauthers, A Victorian Tapestry, 14. Newspaper reports throughout the period indicate an official policy of tolerance. At a public enquiry into the conduct of Victoria police officers, several officers testified that they were under instructions not to prosecute women in the area for prostitution. One police officer testified that “prosecutions in the cases of bawdy houses [on Chatham Street] had not been instituted unless disturbances occurred.” Victoria Daily Colonist (11 November 1899).

-

[51]

In the intervening years, Amor de Cosmos had served as premier of British Columbia and Victoria’s Member of Parliament.

-

[52]

Tax assessment records for 1881, 1891, and 1901 have been transcribed and are available at viHistory, see note 25. Tax assessment rolls for other years are held in the City of Victoria Archives.

-

[53]

Linda J. Eversole, Stella: Unrepentant Madam (Surrey, B.C.: Touchwood Editions, 2005).

-

[54]

Testifying at the enquiry on Victoria Police Commissioners in 1910, Langley recalled, “in 1900, when [I] took office, there were some 275, or 280, maybe 300 known prostitutes in the city.” Victoria Daily Times (5 April 1910).

-

[55]

The population of the city of Victoria during the period examined in this study was 3,270 (1871); 5,925 (1881); 16,841 (1891); 20,919 (1901); and 31,660 (1911).

-

[56]

According to the 1901 census, there were 1,356 unmarried white females, between the ages of 17 and 31 years, in Victoria City. Of that number, 52 per cent (706 females) were not identified with an occupation, so their occupation appears as “none or unknown” in the census data. However, in this demographic cohort, 650 females (48 per cent) were identified with an occupation on the census. Occupational groups having 20 or more female workers are as follows: dressmaker (86); teacher (62); general servant (56); domestic servant (49); stenographer (47); nurse (41); clerk (32); milliner (26). Fourth decennial census of Canada, Victoria City enumeration district. Online at viHistory, see note 25.

-

[57]

Victoria Daily Colonist (13 June 1889).

-

[58]

Ibid. (16 December 1898).