Abstracts

Abstract

This study of the McCord National Museum in Montreal examines the role of place in the creation of personal and public memory. The founder, David Ross McCord, sought to promote a version of Canadian history in which family and personal myth were conflated with that of nation. McCord’s highly personal narrative of Canadian origins was conceived in the private space of the home and was made manifest through the repetitive act of remembering.

Résumé

Cette étude du musée national McCord de Montréal examine le rôle de l’emplacement dans la création de la mémoire personnelle et publique. Son fondateur, David Ross McCord, a cherché à mettre en valeur une version de l’histoire du Canada dans laquelle les mythes familiaux et personnels se fondaient avec celui de la nation. Le récit très personnel de McCord sur les origines du Canada a été conçu dans l’enceinte privée de sa demeure et se manifeste à travers l’acte répétitif de la remémoration.

Article body

If environment, like Highlands of Scotland are credited with the production of certain habits of mind and sentiments it may not be unlikely that the position and the classic form of this the only place of abode I have known, under Providence have not been without their influences on my character.[1]

David Ross McCord

As we change and grow throughout our lives, our psychological development is punctuated not only by meaningful emotional relationships with people, but also by close, affective ties with a number of significant physical environments, beginning in childhood.[2]

Clare Cooper Marcus

I

David Ross McCord (1844–1930), founder of the McCord National Museum, was a lawyer by profession but a collector by vocation. In his McGill-sponsored museum in downtown Montréal, founded in 1921, McCord sought to promote a myth of Canadian origins narrated by objects from his personal collection.[3] Integral to this history was the story of the McCord family, their arrival on this continent and their rise to social prominence. In McCord’s version of Canadian history, family and personal myth were conflated with nation.

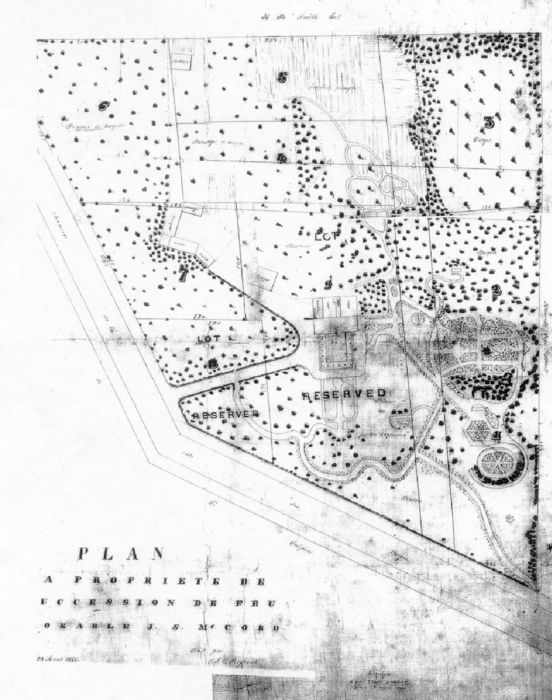

Figure

McCord’s highly personal narrative of Canadian origins was conceived in the private space of home and made manifest through the repetitive act of remembering. In McCord’s narrative, the family home of Temple Grove played a central role: it was where his memories first began. The fourth-born in a family of six children, McCord was the only one of his siblings to occupy the home and gardens over an entire lifetime. For this reason, and others I will explore, Temple Grove was woven into the fabric of the historical narrative he created for his museum.

Similar to the memory palaces devised by classical orators who combined place and image to extend their memories, Temple Grove acted as McCord’s mnemonic template. Surrounded by the familiar objects and views of his childhood, Temple Grove was where the past was most present for David McCord and where recollection was made easy.

The study of collections has come into its own in the last 20 years with the proliferation and expansion of museums in North America and Europe.[4] A relatively new field of enquiry called Collecting Studies, itself a sub-genre of material culture, now dominates museum studies.[5] Although interdisciplinary in approach, a consensus has appeared in the literature with writers focusing on why people collect rather than on the collections themselves. Collecting is thus treated as a cultural process rather than as cultural history.[6] Postwar intellectual currents that have shaped the direction of collecting studies include psychoanalysis, the turn towards structural linguistics, and post-Marxist critiques of ideology and the production of knowledge.

Popular among collecting theorists is the idea that objects are, in the words of Stephen Bann, “signs bearing a message.” According to British collecting theorist Susan Pearce: “The broad structural/linguistic tradition has transformed the study of material culture in its suggestion that objects may be viewed as an act of communication, as a ‘language system’ like mythology and literature.”[7] Mieke Bal, who has written extensively on collecting from a narrative perspective, sees objects as part of a semiotic system which communicates a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.[8] Bann’s book on collecting takes as its subject John Bargrave, a mid-seventeenth-century Kentish gentleman and Vice-Dean of Canterbury Cathedral. Bann makes the case that Bargrave, though an obscure figure, was important to the history of collecting and museums because he was a man devoted to signifying, to making meaning with objects. “Yet each object that he collected was intensely semiophoric: it was a sign bearing a message, as his own written catalogue abundantly testifies. In that sense, he was consistently freeing objects from their ‘utilitarian’ function and constituting them as sign bearers.”[9] According to Bann, the meanings Bargrave attributed to the objects in his collection were self-referential, and the catalogue he produced was a “scrambled biography.”

One of the most original contributions to collecting theory is Susan Stewart’s book, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. The longing Stewart refers to is the longing for authentic or unmediated experience. She writes:

Within the development of culture under an exchange economy, the search for authentic experience and, correlatively, the search for the authentic object become critical. As experience is increasingly mediated and abstracted, the lived relation of the body to the phenomenological world is replaced by a nostalgic myth of contact and presence. ‘Authentic’ experience becomes both elusive and allusive as it is placed beyond the horizon of present lived experience, the beyond in which the antique, the pastoral, the exotic, and the other fictive domains are articulated. In this process of distancing, the memory of the body is replaced by the memory of the object, a memory standing outside the self and thus presenting both a surplus and lack of significance. The experience of the object lies outside the body’s experience – it is saturated with meanings that will never be fully revealed to us.[10]

Like Bann and others, Stewart is interested in the act of recontextualization. What happens to one’s experience of an object when the object is “denatured’ or taken out of its original context? Her explanations seem to come closest to approximating an understanding of what motivated McCord to collect. His collection filled no material need, nor was it valuable in a strictly monetary sense. What Stewart suggests is that the need to collect arises out of the insatiable demands of nostalgia.

II

Built by John Samuel McCord in the imposing style of Greek Revival, the Temple Grove house and gardens were prominently situated on the southern flank of Mount Royal. Begun as a summer retreat for the McCord family, the mountain property became the family’s permanent residence following the birth of David Ross McCord in the spring of 1844. At the time of their marriage in 1832, John Samuel and Anne Ross McCord lived in a house on St. James Street near Anne Ross’ parents. But with four children under five and more babies anticipated, the McCords were concerned with the threat posed by cholera and typhus, two deadly diseases that thrived during the summer months in Montréal’s crowded streets.

The cholera epidemic of 1832 had inspired an exodus to the countryside among people like the McCords who could afford the cost of building a villa. Infectious diseases were one factor, but so, too, was changing fashion as applied to residential architecture. The influence of the Romantic Movement, with its emphasis on the ‘natural’, also helped shape people’s perceptions of the good life. Large landscaped gardens in the English style became an integral part of genteel living: “[T]he garden marked the distinction between the farm, which exploited nature, and the suburban home, which celebrated it.”[11]

One of John Samuel’s main pastimes was designing an extensive garden on the land surrounding Temple Grove, a project which would have been impossible to carry out in the more restricted space available on St. James Street. The state of Montréal’s streets, and the overcrowding of the city generally, was probably inducement enough, however, to locate further a field. Instead of working to improve the health of the city, a task David McCord and his generation of conservative urban reformers would take up with some zeal four decades later, John Samuel and his community chose to flee it.

Country houses were also important on a symbolic level. The choice of location, size, and design, were measures of the kind of social power to which their owners aspired. For those who sought positions of leadership in Lower Canada in the 1830s, land was a potent symbol of having arrived at the pinnacle of colonial society. Although Montréal’s first millionaires had made their fortune in furs, it did not stop them from moving to the countryside in imitation of the British gentry, whose wealth was dependent on land. When John Samuel relocated to the slopes of Mount Royal, he was following the path of upward mobility trod by the fur barons McTavish and McGill, the first English-speakers to colonize the Mountain over 30 years before. His own family’s wealth had come from a collection of leases in Griffintown that had the good fortune to be in the path of Montréal’s first industrial development. Building on the land that would become Temple Grove was a good investment, but the design he chose spoke volumes.[12]

John Samuel’s choice of Greek Revival for his summer home was not an obvious one. Temple Grove was unique in Montréal’s built environment.[13] There were other examples of the Greek Revival style in the city at the time, most notably the Customs House and the Arts building of McGill University, but these were buildings intended for public use. In any case, neither building incorporated the characteristic three-sided structure with porticos that made Temple Grove so distinctive.

In Conrad Graham’s Mont Royal. Early Plans and Views of Montreal, Paul Adams is credited with designing Temple Grove,[14] but it is likely that John Samuel also had a hand in the process.[15] There were few practicing architects in Montréal at the time and many builders relied on models found in various architectural handbooks and engravings then in circulation.[16] John Samuel’s sketch books contain plans for the garden at Temple Grove and architectural details of the house, including a design for the fence which was later constructed along its southern perimeter, as well as a drawing of the projected Protestant Orphan’s Asylum building of which he was a patron.[17]

Building a house in the shape of a Greek temple with the main room exposed on three sides was an impractical if not entirely whimsical gesture, especially in Montréal’s climate. In 1837 and 1838 when Temple Grove was being built, not insignificantly years of rebellion and turmoil, John Samuel was still negotiating his place among Montréal’s governing élite. Temple Grove’s distinctive shape and location gave it the advantage of being an instant landmark. In the words of David McCord:

My father like all educated men of his day was brought up on the classics and he said to me — ‘I looked upon the site I had selected for my country home — and its dominant position — and said to myself the Greeks would have built a Temple — and so shall I’ — He was too well informed to place two stories under a Greek pediment and so he constructed the Doric III [sided] hypaethial structure.[18]

John Samuel McCord was not only well versed in the classics, including classical architecture, he also subscribed to the Ancients’ faith in traditional hierarchies as a means to maintaining social order. The democracy of the ‘polis’ did not extend beyond a very narrowly defined élite who assumed the “burden” of leadership by virtue of their inherited status and their male superiority. Historian George Mosse makes the point, “Conservatives believed that maintenance of freedom was only possible within the framework of historical tradition: ideas of natural law and of progress had led to the collapse of order into revolution. Only through an emphasis on history and the hierarchical system which tradition, that is, history, sanctified could order and therefore liberty be preserved.”[19] A home in the Greek revival style demonstrated a sympathy with this view.

In her research on nineteenth-century villas in Québec, France Gagnon-Pratte found only two examples of the Greek Revival style in Lower-Canadian domestic architecture: Temple Grove and the Caldwell Manor at Bois-de-Coulonges, which later became Governor General Lord Elgin’s residence in Québec City.[20] As Harold Kalman mentions in his A History of Canadian Architecture, the Greek temple was not a structure easily adapted to the Canadian climate. Roger Kennedy, former director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, provides another explanation than simply climate for why examples of Greek Revival architecture were so rare in this country: “The Revival was seen as an American patriotic statement, distasteful to the descendants of Tory emigrants resettled in Ontario and to Spaniards who were citizens of the United States by conquest.”[21]

John Samuel was a staunch Tory as well as being an amateur meteorologist with an extensive knowledge of Montréal’s climatic conditions. Why then would Greek Revival, with its political and practical shortcomings, be so attractive to him? It was said to be cheaper to build in that style than in others and that may well have been a factor. But more likely, the appeal lay in its symbolic value. Buildings are coded for their semiotic functions. By choosing Greek Revival, a civic architecture used in government buildings and universities, John Samuel was showing his approval of ancient Greek ideas about citizenship. Like Plato in his Republic, John Samuel’s conception of democracy did not extend to all individuals. In a diary entry made following the local parliamentary election of 1848, in which the French Canadian leader Lafontaine was re-elected, John Samuel commented: “…spring gradually approaching — when is all this democratic spirit to end — is the world to assume throughout a republican garb! The prospect is very far from encouraging.”[22] What qualified an individual for citizenship was gender, social class, and ethnicity.

While Temple Grove was under construction, John Samuel was otherwise engaged in putting down Patriote attempts to topple British rule in the colony. A lieutenant colonel of the Royal Montreal Calvary and the commander of the 1st volunteer brigade, he took on the task of protecting the city from rebel attacks.[23] When Patriote agitation turned to armed insurrection in the fall of 1837, the combined force of the British Army and the Royal Montreal Cavalry, English-speaking loyalists led by John Samuel McCord, were called upon to squelch the rebellion.[24]

For the local colonial administrators and their allies, the English Protestant merchants, 1838 marked a decisive turning point in political and economic fortunes in Lower Canada. With the defeat of the Patriotes, the forces of liberalism and republicanism in Lower Canada were temporarily obliterated from the political map. The members of the English-speaking élite were finally in a position to impose their agenda on the colony without interference from their political foes, the Patriotes.[25]

The Constitutionalists were a bigoted lot. They supported legislative union with Upper Canada because it promised to reduce French Canadians to a minority within this larger federation. Legislative union was a step on the road to what they hoped would be the complete assimilation of French Canada. British governing classes both at home and abroad saw themselves, to borrow an expression from David Cannadine, “… as the lords of all the world and … of humankind. They placed themselves at the top of the scale of civilization and achievement, they ranked all other races in descending order beneath them, according to their relative merits (and demerits)….”[26] Montréal’s colonial élite were no different; they, too, imagined themselves the superiors of both the French Canadians and that other subject race, Canada’s Native peoples.[27]

Montréal’s English-speaking élite may have been liberals when it came to economics, but they otherwise held views that were unequivocally conservative. For a brief moment in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, this dominant class would seek to impose its English view of the world in the face of what its members perceived as the impending disorder caused by the presence of a Catholic, French-speaking majority, in a Protestant, English-speaking colony. They had less difficulty assuming their authority over the Native population. Contempt for the non-white races, whether African or indigenous, was an integral part of British colonial attitudes all along the coast of America, from Newfoundland to the Carolinas.[28]

Emboldened by their victory over the French Canadian Patriotes and by a demographic shift that made English the dominant language in Montréal, the defenders of British colonialism in Lower Canada sought to inscribe these new relations of power in the urban landscape.[29] Frank Turner writes that Europeans showed a renewed interest in Greek antiquity in the period following the French Revolution when the expression of Enlightenment ideas were upsetting the old order inherited from the Roman and Christian past. Some turned to Greece to justify contemporary changes while others, such as John Samuel and his friends, sought to repudiate the Enlightenment and the French Revolution that it was thought to have spawned.[30]

John Samuel and the governors of McGill University did not find Greek Revival distasteful to their Tory sensibilities perhaps because, like their American counterparts, it enabled them to denote a new order and refashion the city in their own likeness.[31] Their ‘New Town’ rising on the southern slopes of Mount Royal would be everything ‘Vieux Montréal’ was not: clean and uncrowded, broad boulevards lined with monuments to English entrepreneurship and culture, a celebration of the British colonial tie.

Figure

John Samuel’s purchase of property on the Côte-des-Neiges Road in 1835 placed him in the vanguard of wealthy English-speaking Montréalers who in the half century that followed abandoned the original French settlement on the banks of the St. Lawrence River for the higher elevations of Mount Royal. As a community, New Town would be characterized by its material wealth, its linguistic and religious homogeneity, and its colonial imitations of British high culture. Colonizing the Mountain was a bold but necessary move for a community bent on Anglicization. Temple Grove may have been planned before the Rebellions of 1837–1838, but its location and design were reactions to the perceived need to affirm English colonial dominance at the time.

III

When John Samuel McCord died in 1865, Temple Grove was put up for sale by his widow. Without her husband’s income the property proved too expensive to keep. When no buyer was forthcoming, Anne Ross, with the help of her son David, placed a mortgage on the property, the first of many mortgages that David Ross McCord initiated — collecting Canadiana would prove to be an expensive habit for a connoisseur of fading fortunes and a lackadaisical law practice.[32] Five years later Anne Ross died leaving the house, its contents, and the grounds, to be split four ways among her surviving children. In practice, only David McCord and his two sisters, Jane and Annie, lived on at Temple Grove. Robert Arthur McCord, the youngest son, had left home on the day of his father’s funeral to take up a commission in the British Army. As executor of his parents’ will, and with power of attorney over his brother’s affairs, David McCord was left with the power to control the fate of Temple Grove.

One of David McCord’s first acts as master of Temple Grove was to commission a series of scenic views from the Montréal photographer Alexander Henderson.[33] Compiled sometime around 1871, the McCord Red album (so named for its red leather covers) was made up of 48 albumen prints, most of which were stock photographs of rural landscapes from the area around Montréal. It is the first nine photographs however, taken of three McCord houses, which reveal the provenance of this album.

As Martha Langford points out in her book-length study of photographic albums found in the McCord Museum, Henderson photographed four McCord houses, not just the three included in the album: two houses that had belonged to David Ross McCord’s grandfather Thomas McCord, located on the Nazareth Fief; Temple Grove built by John Samuel, as well as the house built by his namesake, David Ross, his maternal grandfather, on the Champ de Mars.[34] However, David McCord’s decision to exclude the photo of his maternal grandfather’s house from the collection makes the album into a straightforward genealogical statement. Another omission (less conspicuous because it was never commissioned in the first place), was an image of his great-grandfather’s house still standing in Québec City. John McCord’s stone tavern, it would appear, did not lend itself to the kind of architectural genealogy David was now trying to construct for himself.

Figure

Figure

As the Henderson photographs show, the big attraction at Temple Grove was the garden. A student of natural science, John Samuel used his garden as a place of experimentation, bringing together old world plants with new world conditions. In 1898, local writer Richard Starke published an article describing the Temple Grove gardens in The Canadian Horticultural Magazine.[35] The article provides the following description of the gardens of his childhood as remembered by David McCord some 40 years later:

The long shrubberies and more conventional parterres perfumed the air, or displayed in scores of beds what our climate permitted to be grown of the perennials and annuals. A rustic bridge, covered with vines, spanned a ravine and terminated in an arbour, one of the many that suggested a book or thought. Honeysuckles, or Espalier Roses, ten feet in height adorned the walks. The place was a succession of gracefully broken surfaces, and the paths followed them. The theory of the garden was to be directed by nature rather than direct her, and the success of the result proved the correctness of the theory. There was hardly a straight walk, and there were acres of them.[36]

In Starke’s estimation the garden was extensive, covering most of the eight arpents lot, beginning at Côte-des-Neiges Road and continuing up the Mountain. Designed by its owner after the picturesque style first introduced to England in the eighteenth century, the garden ultimately included a folly (naturally occurring), a winding path with foot bridges, a Victoria seat where visitors were encouraged to pause and admire the view, a croquet field, and a summer house donated by David Ross as a gift to his daughter Anne.[37]

In the next generation, under David McCord’s influence, Temple Grove gradually and irreversibly descended into the realm of the fanciful. The change could be measured by a number of alterations to garden and house, which were minor, but together amounted to a powerful statement about the new direction of Temple Grove.

Sometime in the 1880s, after his marriage to Letitia Chambers, David McCord undertook to create a facsimile of the battlefield of the Plains of Abraham in his front yard. The main walkway and entrance steps to Temple Grove were altered to recreate the dimensions of the famous battlefield at Québec.[38]

The distance between this terrace and the road is the famous forty yards on the Plains of Abraham — the forty yards which as effectively transferred a continent to Britain as did the treaty of the succeeding year at Montreal. The height of this terrace above the lawn is the advantage of the position which the French had over Wolfe’s army on the Plains. The steps there in the path to the house are twelve in number. They represent the twelve regiments in Wolfe’s army. Look at them …. The first is the 15th regiment, the next is the 28th, then the 35th, the 43rd, the 47th, the 48th, the 58th, the Monkton, the 60th, the 78th, the Highlanders, and the Louisburg Grenadiers, (I give the regiments from memory, and may be wrong in some details).[39]

In this excavation of rock and earth could be discerned the contours of McCord’s symbolic universe.

Whereas John Samuel had looked to the ancient Greeks for an aesthetic vocabulary in which to couch his social aspirations, his son would choose his materials from a past closer in proximity to his own time and place. France and England, Montcalm and Wolfe, soldier and Indian: each locked in deadly combat for the prize of North America, a story as epic as anything found in the annals of ancient Greece.[40] McCord had a tradition to invent and this would be his foundational story.[41] The Battle worked beautifully in this regard by signaling both the ascendancy of the British in North America, and the arrival of the McCords on this continent.

Creating a distinctly Canadian heroic genealogy of masculine origins was one of David Ross McCord’s principal preoccupations. Much of his collection commemorated military campaigns and their leaders: the war-bonnet allegedly worn by Tecumseh; Native war hero Joseph Brant’s skull; and the largest collection of Wolfeiana in the world, an assertion McCord made with much pride.[42] McCord’s claims to authority came from his identification with the marshal class. In his letters to potential supporters he would often cite his relationship to previous generations of extended family members who had proven themselves on the battlefield. In his referencing of the landed gentry and their role as bearer of arms, he was also aligning himself with their hereditary right to lead.[43]

Inside the house, there were more signs of McCord’s re-ordering of domestic priorities. In rooms that displayed enough clutter to qualify as high Victorian, the personal effects of four generations of McCords mixed with other historical markers from Canada’s past. Human relics conserved under glass bell-jars competed with Worcester tea sets, furnishings, Native objects of all descriptions, and a panoply of military hardware, in a promiscuous mingling of personal object with historical artifact.[44] What at first glance appeared as so much collected chaos revealed upon repeated viewings an order and system of classification, which expressed through its many idiosyncrasies the world-view of its owner, David Ross McCord.[45]

Figure

The main floor was divided into library, picture gallery, Canada Room and West Room. The drawing room became Canada Room where his mother’s art was on display; the hallway, the official picture gallery home to General Brock’s sword and 39 oil paintings depicting the history of Canada; the dining room now the West Room contained the James Wolfe collection including an eight-foot panoramic view of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. In the library was kept ‘Tecumseh’s War Bonnet’.[46]

Figure

As McCord’s collection grew, rooms that had once formed the backdrop for family celebrations and gatherings of Montréal’s colonial élite were re-inscribed with meanings derived exclusively from the past and renamed in consequence of their new functions. Signs of death and commemoration proliferated. In an interview with a British journalist in 1910, McCord stated bluntly, “I am in collaboration with the dead.”[47] This orientation was even more apparent in the interior, where rooms that had been designed to accommodate the needs of a growing family now served as home to thousands of historical relics that McCord referred to as “my children.”[48]

In the interior spaces of Temple Grove, McCord subjected the remnants of history to the routine and ritual of domestic life and in so doing, symbolically reconfigured history to fit the measure of private space and time. In McCord’s virtuoso collecting performance, objects substituted for people and past events. In Susan Stewart’s words, “The souvenir reduces the public, the monumental, and the three-dimensional into the miniature, that which can be enveloped by the body, or into the two-dimensional representation, that which can be appropriated within the privatized view of the individual subject.”[49] Within the private world of the McCord family residence, David McCord nourished his own subjective view of the past with the things he imbued with his own historical meanings.

This blurring of distinctions between private and public was the outcome of McCord’s passionate desire to turn the fruits of his collecting, an obsessive practice pursued in private, into a national monument supported by public monies. As the architecture that literally contained this project, Temple Grove acted as an important signifier, imbuing each object with meaning and context. It is not without import then that what would become the McCord National Museum began in a Doric-columned mansion perched on the Mountain overlooking Griffintown, the squalid working-class neighbourhood whose existence had made Temple Grove possible. John Samuel McCord had used Greek Revival to make a straightforward personal statement about social power. David Ross McCord, on the other hand, had a more far-reaching purpose. He wanted to make the Ancients part of the Canadian cannon. By filling his Greek temple with Canadiana, he was updating Greek Revival and imbuing it with a distinctively Canadian significance.

When museum building became McCord’s raison d’être, guiding visitors through the cluttered rooms of Temple Grove not only gave him the opportunity to show off his dramatic skills as a story-teller, but also became one of the principal ways he had of attracting support for his museum. Journalist C. Lintern Sibley captured one such performance for posterity by allowing us a glimpse of David McCord in his storyteller persona describing the final moments of the now famous battle. Costumed in the silk robe of a Japanese nobleman, he stands pointing to the steps of Temple Grove named for Wolfe’s regiments:

Now listen, can’t you hear the conquering volley of that gallant British Army ringing down through the centuries? Can’t you see the gallant British Army rushing the position of the equally gallant French? The battle, short and sharp, is over. Quebec has capitulated. The fate of the continent is decided - and you and I are here![50]

In this performance, McCord need not be the aging “Golden Square Mile” eccentric, but the director of the most important mise-en-scène in the Canadian historical canon: the titanic struggle for possession of the North American continent waged by the French and English Empires on a small battlefield at Québec.

The re-creation of the battlefield of the Plains of Abraham in his front yard was the dramatic gesture of a man who invested heavily in his role as vicarious witness to history-making events. Unlike previous generations of McCord men, the younger McCord preferred to review the upheavals of history from a reflective distance. His influence lay in the power to interpret, but by working from the margins of the historical process he was dependent on those at the centre of public life, the businessmen, politicians, and academics, to bring his historical vision to the public. Given the times in which he was living, his interpretative authority would prove to be an unreliable source of power.

Just as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham marked the end of the French absolutist presence in the new world, McCord too found himself on the wrong side of history-changing events. McCord’s motivation for wanting to create a museum with his collection can be understood in light of what American historian Richard Hofstadter has identified as the status revolution: a “changed pattern in the distribution of deference and power” that took place during the closing decades of the nineteenth century and early in the twentieth century.[51] Writing about the United States, Hofstadter describes the negative impact of change wrought by the growth of cities, rapid industrialization, the construction of railways, and the emergence of the corporation as the dominant form of business organization, on a group he referred to as the “Mugwump type” (old gentry, established professional men, small manufacturers, and local merchants). Overtaken by the greater wealth and power of a new social class, made up of corporate managers and industrialists, the old élite saw their status and influence radically decline in relation to the newly wealthy. The social dynamics Hofstadter ascribes to industrializing United States were North America-wide.[52] In this context, McCord’s museum project can be seen as an attempt at regaining lost prestige, both for his family and for the social class to which they belonged.

IV

By the time Sibley’s article on Temple Grove appeared in Maclean’s Magazine in 1914, the house was already known to Montréalers as the “Indian museum.” The years leading up to the Great War had been propitious ones as far collecting Native artifacts were concerned. A steady flow of objects threatened to swallow up every available space in the McCord home, including the bedrooms on the floor above. If David McCord was to continue to collect, he needed a new space in which to expand his collection.

For a decade he had been trying to give his collection away to a variety of institutions without much success. Frustrated by the effort, he wrote to his friend, W.D. Lighthall: “I am weary of trying to give away precious things!!”[53] What he sought and what was proving elusive to find was an institution, preferably an educational one, that would agree to provide him with a building and money for the maintenance of his collection. He would continue to pay for new acquisitions with his own revenues, or that was the plan. McGill University had been the main object of David McCord’s attentions since 1909. But the university had been reluctant to accept his gift, fearing that it had the potential of becoming a financial albatross.[54]

In the rest of the world, events were taking a turn for the worse. The war in Europe was at a stalemate with huge losses of life on both sides. On 1 July, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, expected to be the decisive and winning battle of the war, Britain suffered the greatest loss of life in its entire military history.[55] That Britain, which controlled a quarter of the earth’s surface, was unable to advance more than a few yards on a French battlefield demonstrated to the world that its superiority was no longer absolute. McCord had friends and family who had sent their sons to fight overseas. He was also a committed anglophile. The news was devastating.

In the summer of 1916 a series of photographs were taken of McCord in his study at Temple Grove. One of the images, now used by the current McCord Museum for its advertising, shows him seated at his desk. Behind him is a wall of books encased in glass cabinets. In his hands he holds a book open at a photograph, finger poised to turn the page. Light coming from a window opposite illuminates his face, head, and hands, as well as the books at his back, but leaves the rest of the frame in darkness.

Figure

Examined quickly the photograph shows a scholar of mature years at work in his study. It is a dignified if not solemn portrait. David McCord does not face the camera but looks at the photographer from an angle, askance. Is he annoyed at the interruption in his work or is it suspicion that plays on his face? The other photographs confirm the annoyance. In most of the frames he does not even look at the photographer. These shots are more candid and reveal the face of a deeply troubled man. In 1922, David McCord was diagnosed with homicidal dementia, but in this set of photographs the signs were already there.[56] Although it was another six years before he would be admitted to the Protestant Hospital for the Insane, David McCord’s mental and physical health had already begun to deteriorate.

Fearing he was approaching the end of his life, McCord began to redouble his efforts at cataloguing his collection. In his youth, he had learned the practices of inventory science from his father and from his participation in the Natural History Society. His training had taught him the importance of record-keeping and written documentation as a way of establishing the provenance of objects. “I have subordinated all other considerations to those of truth — the soul of history. The size of stones in buildings have been marked and the courses of the masonry counted, the number of the panes of glass indicated and the construction of the beams of roofs correctly represented … No detail has been too insignificant for reproduction.”[57]

With poor health restricting his movements, McCord slowly sifted through the thousands of objects stored in his childhood home, Temple Grove, the only home he knew. Examining, labeling, and recording is a long and painstaking process, involving the hand and eye in a choreography of remembrance. Experts say that the past revisits us in old age, our capacity for immediate recall diminishes while our long-term autobiographical memory becomes more present.[58] With pen in hand David McCord inscribed on the back of one of his most cherished possessions, the Bartlett print purchased from W.D. Lighthall:

It is interesting to mark the pediment and wings of Temple Grove in this Bartlett picture especially coupled with my destiny in having collected here the materials for the National Museum, to bear my name …. The pillars and pediment of Temple Grove have been the dominant feature of the Mountain in all general pictures of Montreal, since its creation. This on the back of which I now write was the first of such since the house was built in 1837 or 8 and so it has been down to the great commercial picture of a few years ago by Wiseman. In my large Duncan picture of 1832 painted for my father it does such, of course, appear. The trees have grown very much in this interval. There is an example of such in the comparatively small size at the present a great white birch on the left of the observer as portrayed in my large view of the city by this same artist of 1851 or 52 painted for Dr. McCulloch and taken from this very Temple Grove garden! When our old friend John Kerry came out to this country from England in November 1849, by way of New York, Lake Champlain, St. Johns and finally crossed the river from Laprairie the principal object which met his eye on the side of the mountain overlooking the city where he had elected to make his home was these pillars and the pediment. This Mr. Kerry told me himself and he repeated it to his son, who to-day communicated to me the year of his arrival.[59]

But the watercolour was not a painting by W.D. Bartlett.[60] Nor was it entitled “The Principal View of Montreal.” Confusion over name and origins still further compounded, he writes “of the pediment and wings” of Temple Grove even though none are visible.

Nonetheless, in both the original Bartlett sketch and the copy owned by McCord, Temple Grove appears as a small, barely distinguishable smudge against the more imposing but equally undefined flank of Mount Royal. In McCord’s exaggerated rendering of “The Principal View,” Temple Grove is embellished with architectural details that make it the “dominant feature of the Mountain in all general pictures of Montreal since its creation.”

While Temple Grove was probably the most visible landmark on Mount Royal in 1838 and in the decades that followed — only the McTavish monument was positioned to make a similar claim on the eye — neither the McCord copy nor Bartlett’s original provide confirmation of McCord’s subjective view. Why then did McCord select “The Principal View of Montreal” as his memory board when other scenes, James Duncan’s “View from Temple Grove,” for example, commissioned by his father and presented to him on his 21st birthday, were souvenirs of a more personal kind? Why is this picture so susceptible to misrepresentation? And finally what does his remaking of “The Principal View” tell us about his “habits of mind and sentiments,” and of his place in the imagined world of this Bartlett painting?

The watercolour McCord attributed to Bartlett was actually a copy of a Bartlett engraving entitled “Montreal from the St. Lawrence,” found reproduced in Nathaniel Parker Willis’s Canadian Scenery. A journeyman artist trained in architectural drawing, W.D. Bartlett made his living painting picturesque scenes of England, Europe, and the Middle East that were used to illustrate travel books. In 1836–1837, 1838, and again in 1841, Bartlett visited North America to make the preliminary sketches for two books of the same genre, American Scenery and Canadian Scenery.[61]

Figure

Bartlett’s engraving was faithful to its title, “Montreal from the St. Lawrence,” and depicted Montréal in 1838 as a pre-industrial port from the vantage point of the river. The largest object in the drawing appears in the foreground: a log raft transporting passengers, one of whom has raised his arm in salutation to a passing ship. The activities on the river unfold before the backdrop of Montréal’s built environment. On this second visual plain the eye is centered by the towers belonging to the former Notre Dame Church and to the Anglican Church, providing a frame within a frame for Notre Dame Cathedral, the only distinguishing landmark in a scene otherwise bereft of architectural detail. Halfway up the mountain Temple Grove appears as a dark shadow on its slope.

Bartlett’s reputation as an artist was based on his ability to render foreign scenes recognizable and picturesque to a public, the vast majority of whom were English and whose experience of distant places was limited to the perusal of travel books. To such an audience, exoticism was easy to conjure and sell. This may explain why Montréal appears more Mediterranean port than principal city of British North America, more ancient than modern. The twin summits of Mount Royal provide a touch of the picturesque, an expression of nature that naturalizes the socio-political arrangements captured by this frame.

In England the picturesque perpetuated an idealized version of rural landscape that was quickly passing from view. Coming at the height of the agricultural transformation of the countryside, the picturesque was suited to express the complexity of the historical moment. In its celebration of the irregular, pre-enclosed landscape, the picturesque harkened back nostalgically to an old order of rural paternalism. In its portrayal of dilapidation and ruin, the picturesque sentimentalized the loss of this old order.[62]

In Lower Canada, the issue was not enclosure but the replacement of the French seigneurial system with British freehold land tenure. John Samuel McCord was one of the early members of the seigneurial commission set up to negotiate the complexities of this dual system.[63] The growing pressure to make a commodity out of land was reshaping the natural landscape, but it was a French ‘nature’ that was being reconstituted from an English point of view.[64]

Bartlett (unwittingly or not) represented this struggle over land by showing the Mountain in its natural state, devoid of peasant holdings and symbols of private property. The only exception is John Samuel McCord’s new summer house, Temple Grove, completed the same year as the sketch. Although barely visible, Temple Grove was nonetheless a sign of the times, an indicator of the direction land-use would soon take in the area bordered by the Mountain. In the “Principal View,” time stops at the summer of 1838 just as Montréal hovers on the brink of the Industrial Revolution and political rebellion.

In 1838 the English Protestant mercantile class was still dreaming of making their city the centre of a vast commercial empire. Montréal’s merchants were envisioning a mega-project of canal building and general improvements paid for by British government loans that would remake the St. Lawrence River into the most important transportation route on the continent. Under this scheme Montréal would replace New York as the principal warehouse for goods passing to and from North America to England. Only the steamboat and its telltale ribbon of smoke hints in the picture at the future changes that would transform this city beyond recognition by century’s end.

The picturesque was an aesthetic of nostalgia, and herein lies its attraction for David Ross McCord. Looking back over the past 80 years of Montréal’s history with his copy of Bartlett’s engraving close at hand, McCord is reviving a pre-industrial Montréal, not yet geographically divided into the post-rebellion “two solitudes,” and still in British hands. It is also the city of his father’s early middle years, when a healthy John Samuel McCord was negotiating his place among the local gentry. It was a city about which his parents, but especially his mother, were prone to tell stories. In 1838 Montréal’s cityscape still bore the traces of its ancien régime origins. The fortifications had been dismantled but the pattern of streets had not changed significantly.[65] During the next 80 years Montréal went from being a small town with a population of 9,000 in 1800 to a modern metropolis of some 300,000 people in 1901.[66] The mass society McCord feared became a reality and the influence of the English waned. For these reasons and more, the moment immortalized by Bartlett’s drawing was important to remember.

Literary critic Evelyn Hinz writes, “nothing so characterizes the archaic mind-set as a concern with origins, and surely this is the distinguishing feature of auto/biography.” David McCord’s interest in origins stemmed from his preoccupation with his place within the family but especially in relation to his father. But that is only part of the story. McCord also saw his life work as “Canada’s handmaiden,” keeper of the traditions on which the country’s greatness would rest for future generations. Hinz continues:

What both also have in common is that the impetus for ritual act derives from a crisis situation or a sense of vulnerability (a feeling of diminished status/power) and both reflect a belief that a return to origins is a means of recuperating lost vitality and stability. Thus, the more we want to argue that auto/biography is not a nostalgic project, the more we should recall that in archaic ritual, too, the return to the past is a way of canceling historical contingencies and of enabling a fresh start.[67]

In 1916, David McCord was in desperate need of a fresh start. His project of opening a museum was falling on deaf ears. The optimism of the Edwardian period was already behind them and, more recently, the failure of Britain to strike a decisive victory on the battlefield during the early stages of the Great War signaled its continued decline. The stimulus to return to the past in order to re-invent a future was coming from all directions. David Ross McCord’s refuge, Temple Grove, was now on the streetcar line. His health and that of his wife Letitia’s was failing, the servants were difficult, and the property heavily mortgaged and in need of repair. It is no wonder David McCord wanted to start over in a new building. But wherever he went, Temple Grove would remain the mnemonic template from which he and, eventually in turn, the McCord Museum on Sherbrooke Street in downtown Montréal, would generate historical meanings. As one of the most important interpreters of Canadian history in this country, the McCord Museum’s origins as a Greek Revival temple on the colonized flank of Mount Royal tells us something about the forces that have come to shape public memory in this country.

Appendices

Biographical Note / Note biographique

Kathryn Harvey

Kathryn Harvey has a Ph.D. in Canadian History from McGill University. After many years in the archives, she has decided to step out into the light, camera in hand. In 2007, she directed the documentary Verdun Memories: Cutting, Pasting & Remembering. She is currently working on two new projects. One is a web based multi-media collection of oral histories from Verdun, Quebec, and the other a year-long cinéma-vérité project set in a Homeless Women’s shelter in Montreal.

Kathryn Harvey détient un doctorat en histoire canadienne de l’Université McGill. Après plusieurs années passées aux archives, elle a décidé de sortir au grand jour, caméra en main. En 2007, elle a dirigé le documentaire Verdun Memories: Cutting, Pasting & Remembering. Elle travaille actuellement à deux nouveaux projets. L’un est une collection multimédia et virtuelle d’histoires orales de Verdun (Québec) et l’autre, un projet de cinéma-vérité tourné au cours de toute une année dans un foyer pour femmes sans-abri de Montréal.

Notes

-

[1]

MCFP, file #2065, “Early Museum Accession Register,” paintings and notes, David McCord, 15 August 1916.

-

[2]

Clare Cooper Marcus, House as a Mirror of Self (Berkeley, CA: Conari Press, 1997), 2.

-

[3]

The McCord Museum still exists on Sherbrooke Street in downtown Montréal, but housed in a different building and called the McCord Museum of Canadian History.

-

[4]

Susan Pearce, “Museum Studies in Material Culture,” in Museum Studies in Material Cultural, ed. Susan Pearce (Leicester: Leicester University, 1989), 1–10.

-

[5]

On collecting and collectors, see Stephen Bann, The Clothing of Clio: A Study of the Representation of History in Nineteenth-Century Britain and France (Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 1984), Stephen Bann, Under the Signs. John Bargrave as Collector, Traveler, and Witness (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994), Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Eugene Rochberg-Halton, The Meaning of Things. Domestic Symbols and the Self (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), John Elsner and Roger Cardinal, eds., The Cultures of Collecting (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), Shepard Krech III, ed., Passionate Hobby (Rhode Island: Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology 1994), Werner Muensterberger, Collecting: An Unruly Passion (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), Susan Pearce, Collecting in Contemporary Practice (London: Sage, 1998), Pearce, ed., Museum Studies, Della Pollock, Exceptional Spaces: Essays in Performance and History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984).

-

[6]

Pearce, Collecting in Contemporary Practice, 10.

-

[7]

Ibid, 6.

-

[8]

Mieke Bal, “Telling Objects: A Narrative Perspective on Collecting,” in The Cultures of Collecting, eds. Elsner and Cardinal, 97–115.

-

[9]

Bann, Under the Signs, 11.

-

[10]

Stewart, On Longing, 133.

-

[11]

Roderick MacLeod, “Salubrious Settings and Fortunate Families: The Making of Montreal’s Golden Square Mile, 1840–1895 (Ph.D. diss., McGill University, 1997), 14.

-

[12]

Mark Girouard, Life in the English Country House (London: Yale University Press, 1978), 3.

-

[13]

Architectural historian Harold Kalman has written the following about Temple Grove in A History of Canadian Architecture, Vol. I (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1994), 303: “Temple Grove was a rare example in Canada of a Greek temple with porticos on three sides. True Greek temples possessed columns on all four sides, but in Canada where the colder climate made this impractical, the Roman temple-form, with a portico on one or both ends was the most popular.”

-

[14]

See Conrad Graham, Mont Royal. Early Plans and Views of Montreal (Montréal: McCord Museum, 1992).

-

[15]

In Neoclassical Architecture in Canada (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1984), Leslie Maitland also names Paul Adams as the person responsible for the construction of Temple Grove.

-

[16]

The first published document from John Ostell’s career as an architect, surveyor, was “Sketch of property of the late John Gray esq.,” signed John Ostell, land surveyor of the Province of Lower Canada. In this period there was no distinction made between surveyor and architect. See Ellen James, John Ostell, Architect, Surveyor (Montréal: McCord Museum, 1985), 13.

-

[17]

According to Ellen James, the earliest image of the Protestant Orphan Asylum on St. Catherine Street, between Peel and Stanley, was a pencil sketch by Eliza Ross, the treasurer and John Samuel’s sister-in-law. The architect who built the Asylum was John Ostell. See James John Ostell, 55. A design of the entrance to the Asylum was also made in John Samuel’s hand and is found in NAC, Summerhill Home, MG 28, I 388, vol. 15, file 5; MG 28, I 388, vol. 14, file 5, Report of the Gentlemen’s Committee appointed to aid the Ladies in the construction of their new asylum on St. Catherine Street, 1851, reel 1716.

-

[18]

MCFP, file #2065, 15 August 1916. Punctuation and emphasis in the original.

-

[19]

George L. Mosse, The Culture of Western Europe (Boulder: Westview Press, 1988), 133.

-

[20]

France Gagnon-Pratte, L’architecture et la nature à Québec au dix-neuvième siècle: les villas, 57. Coincidentally, while living at Monkland’s, the Governor General’s residence in Montréal, Lord Elgin and his family were neighbours of the McCords.

-

[21]

Roger Kennedy, Greek Revival in America (New York: Stewart, Tabon & Chang, 1989), 17.

-

[22]

MCFP, file #410, John Samuel McCord’s diary, 29 April 1848. Punctuation and emphasis in the original.

-

[23]

Pamela Miller, et al., The McCord Family: A passionate vision, 67. Also see Brian Young, “The Volunteer Militia in Lower Canada, 1837-50,” (Montréal: Montréal History Group, 1998).

-

[24]

Miller, et al., The McCord Family, 67. Jean-Paul Bernard, The Rebellions of 1837–38 in Lower Canada (Ottawa: CHA Historical Booklet, No. 55, 1996).

-

[25]

In the aftermath of the Rebellion, colonial administrators with the example of the American rebellion forever before them, moved quickly to strengthen the British presence in the colony. The abolition of French feudal land tenure, improvements to navigation on the St. Lawrence River, the rewriting of the Civil Code to make it more accommodating to British law, and the legislative union of the two Canadas, were all measures that had been proposed by the Constitutionalists. See Miller, et al., The McCord Family, 8.

-

[26]

David Cannadine, Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (Oxford: Oxford University, 2001), 5.

-

[27]

Steve Watt makes a similar argument in, “Authoritarianism, Constitutionalism and the Special Council of Lower Canada, 1838–1841,” (M.A. thesis, McGill University, 1997).

-

[28]

Cannadine, Ornamentalism, 13.

-

[29]

Colin Coates, The Metamorphoses of Landscape and Community in Early Quebec (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 2000), and Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia 1740–1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982).

-

[30]

Frank Turner, The Greek Heritage in Victorian Britain (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1981), 2.

-

[31]

See MacLeod, “Salubrious Settings and Fortunate Families.”

-

[32]

David McCord relied on family inheritance money from his parents to sustain his collecting. Later in life this would bring him into conflict with his surviving siblings who had also inherited from their parents, but whose access to the money remained restricted by him.

-

[33]

Alexander Henderson was the photographer of the Montreal Orphan Asylum. He also shared with David McCord, an avid interest in local history.

-

[34]

Martha Langford, Suspended Conversations (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001), 55.

-

[35]

According to David McCord, most of the article was written from notes that he himself provided.

-

[36]

NAC, Richard Starke, “Note on Old and Modern Gardens of Montreal,” 338.

-

[37]

See John Dixon Hunt, Gardens and the Picturesque (Cambridge, MA.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1992), and Stephanie Ross, What Gardens Mean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

-

[38]

On the origins of the outdoor history museum, see Edward Alexander, Museums in Motion (Nashville: American Association of State and Local History, 1979), 84.

-

[39]

Ibid.

-

[40]

Simon Schama makes a similar point about the work of the Romantic historian Francis Parkman in Dead Certainties (Unwarranted Speculations) (Toronto: Vintage Books, 1992), 49.

-

[41]

See Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition (London: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

-

[42]

C. Lintern Sibley, “An Archipelago of Memories,” MacLean’s Magazine 27 (March 1914).

-

[43]

See J.F.C. Harrison, The Early Victorians, 1832–1851 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971), 89–92.

-

[44]

Newspaper photographs and articles describing the collection from this period attest to McCord’s own style of arrangement. For descriptions of the interior of Temple Grove, see Edgar Collard, “The collector: David McCord,” 100 More Tales from All Our Yesterdays (Montreal: The Gazette, 1990); “Temple Grove: A Revelation,” Westmount News (2 May 1908); Sibley, “An Archipelago of Memories.”

-

[45]

Very little is known about McCord’s earliest collection. His organizational methods, however, were borrowed from natural history. His first collection was of ferns. During the years he was seeking a permanent home for his collection he made an inventory of the objects from which the first accession books for the McCord National Museum were derived. It was a condition imposed by the associations (including McGill University), which he approached for support for his museum.

-

[46]

“Temple Grove: A revelation.”

-

[47]

David McCord, as quoted in The Daily Telegraph (20 October 1910). He repeats this phrase, “the collaboration of the dead,” in MCFP, file #2065, Notes & Suggestions, “(Paul Borget of the French Academy — 1911) Happy expression of what my occupation has been and is here. (A humble disciple of St. Helena).” Punctuation is McCord’s.

-

[48]

NAC, Laurier Papers, MG26G, vol. 287, reel C805, David McCord to Sir Wilfred Laurier, 21 October 1903.

-

[49]

Stewart, On Longing, 137–8.

-

[50]

Sibley, “An Archipelago of Memories.” Sibley also wrote on gardens for Canadian Magazine, “The Gospel of Flowers,” 556 (April 1912).

-

[51]

Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (New York: Vintage, 1955), 135.

-

[52]

J.M.S. Careless, Toronto to 1918: An Illustrated History (Toronto: J. Lorimer, 1984), 149–52.

-

[53]

MCFP, file #2049, David McCord to W.D. Lighthall, June 16, 1909.

-

[54]

Stanley Brice Frost, McGill University for the Advancement of Learning, Vol. II (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1980), 108.

-

[55]

John Keegan wrote, “The Somme marked the end of an age of vital optimism in British life that has never been recovered.” John Keegan, The First World War (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1998), 299.

-

[56]

According to W.D. Lighthall, David McCord drank a bottle of whiskey a day until 1919. Homewood Sanitarium, patient files, David McCord.

-

[57]

MCFP, “Catalogue of Original Paintings in Oil and Water Colour Illustrative of the History of Canada,” Vol. 1.

-

[58]

One of the features of autobiographical memory in the elderly is a tendency to engage in what experts call “life review,” the resolving of past experiences through the reworking of memories from the years ten to 30. See Martin Conway, Autobiographical Memory: An Introduction (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1990), 154.

-

[59]

MCFP, file #2065, “Early Museum Accession Register,” paintings and notes, David McCord, 15 August 1916.

-

[60]

W.D. Bartlett sketched a very similar scene which later appeared as an engraving in Nathaniel Parker Willis’s Canadian Scenery (London: 1840), but according to Conrad Graham, curator of objects at the McCord Museum of Canadian History, it was a copy. Apparently, copying Bartlett engravings was a popular pastime in Montréal during this period.

-

[61]

See W.D. Bartlett by Alexander M. Ross, DCB online, <http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=37890&query=bartlett>, (viewed 5 January 2006).

-

[62]

Ann Bermingham, Landscape and Ideology (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986), 70.

-

[63]

Miller, et al., The McCord Family, 45.

-

[64]

Brian Young makes this same point but with different emphasis when he writes: “commutation must be seen not as a process of ‘Anglicization’ (although that was one possible result), but as part of the larger transition in Lower Canada from feudalism to industrial capitalism.” See Brian Young, In its Corporate Capacity: The Seminary of Montreal As a Business Institution, 1816–1876 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986).

-

[65]

Jean-Claude Robert, Atlas historique de Montréal (Montréal: Libre Expression, 1994), 90, writes that the number of streets increased from 100 to 173 during this period.

-

[66]

See Newton Bosworth, Hochelaga Depicta (Montréal: William Greig, 1839), 88–93, and Jean-Claude Robert, Atlas historique de Montréal (Montréal: Libre Expression, 1994), 78. For a discussion of the changes to Montréal in the 1880s and later, see Richard Hemsley, Looking Back (Montreal, 1930).

-

[67]

Evelyn Hinz, “Mimesis: The Dramatic Lineage of Auto/Biography,” in Essays on Life Writing: From Genre to Critical Practice, ed. Marlene Kadar (Toronto: n.p. 1992), 207.

List of figures

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure