Abstracts

Abstract

As the world slides deeper into recession, ‘child poverty’ rates will undoubtedly increase with rising unemployment, household debt and marriage breakdown. This comparative paper focuses on the gendered aspects of child poverty, showing that Canada has higher rates of maternal employment than some other liberal welfare states but also higher poverty rates for mother-led families, a larger gender gap in pay, and lower levels of social spending on families. The paper argues that the lack of gender analysis in political discourse tends to downplay the well-known association between poverty and female-led households, which requires greater acknowledgement as the recession worsens.

Résumé

Dans un contexte de récession qui s’aggrave de jour en jour dans le monde, il ne fait pas de doute que le niveau de pauvreté infantile augmentera en fonction de la croissance du chômage, de l’endettement des ménages et des séparations. Cette étude comparative met l’accent sur l’influence du genre sur la pauvreté et révèle que le Canada compte un niveau d’emploi maternel plus élevé que quelques autres États providences libéraux. Cependant, il possède aussi un taux plus élevé de pauvreté dans les familles dirigées par les mères, ainsi qu’un écart plus important au plan de la rémunération et un niveau moindre de dépenses relatives aux activités sociales de la famille. Selon cette étude, l’absence d’analyse du genre dans le discours politique tend à minimiser la corrélation notoire entre pauvreté et ménages dirigés par des femmes, un concept qui mérite davantage de reconnaissance en cette période de récession qui s’intensifie.

Article body

Introduction

The concept of ‘child poverty’ has been politically useful for both governments and interest groups across the Canadian political spectrum. Children cannot be blamed for their lack of initiative or poor employment skills, which means that more support for poverty reduction can be gained by strategies focusing on children rather than low-income adults. However, the concept of child poverty also permits users to gloss over the main causes of household poverty, which relate to the state of the economy, employment rates, working conditions, and gendered patterns of paid and unpaid work. Gendering the analysis of poverty could help policy makers to create more realistic strategies to reduce poverty in the deepening economic recession. Furthermore, Canada can learn some lessons from countries that have dealt more effectively with the issue of child poverty.

Researchers and policy makers often disagree about how to measure poverty but ‘child poverty’ is often defined as the percentage of children in a particular jurisdiction living in households with incomes less than 50 per cent of the national median, after taxes and transfers, and adjusted for family size[1] (OECD, Society at a Glance 56). Relative measures are normally used because they are easier to obtain and more conducive to cross-national comparisons. Absolute poverty measures are more complicated to calculate because they assess the cost of necessities, or a market basket of goods, in particular cities or regions. However, researchers have found widespread public agreement with respect to the ‘essentials of life’ and who is missing out because they cannot afford these (Saunders). Sociologists also argue that perceptions of ‘relative deprivation’ are important because they tend to encourage resentment and anti-social behaviours.

We already know that child poverty rates, when measured in terms of relative household income, are influenced by labour market conditions, socio-demographic trends and government policies (UNICEF 17). These rates tend to increase when unemployment rises and wages fall relative to living costs, when more parents separate and children live with their mother, and when governments cut social benefits and services or make them harder to obtain. In contrast, child poverty rates fall when workers become better educated and acquire more skills, when the number of two-earner households increases, when the economy is booming, when wages rise relative to living costs, when couples delay reproduction until they are older and consequently produce fewer children, and when governments improve social benefit programs (UNICEF 17). In other words, child poverty rates have little to do with children themselves, but are influenced by overall economic conditions and factors impacting the family finances, their living arrangements and the work their parents’ do. It must also be noted that state support for parenting affects poverty rates.

This paper focuses on the gendered aspects of child poverty in Canada, making comparisons with other ‘liberal’ welfare states, although this label has been disputed for some of these countries. The states selected for comparison are the mainly English-speaking countries of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States because they share similar systems of social provision and government regulation (Esping-Andersen; O’Connor et al.). The paper uses mainly international statistics from the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) but also national and qualitative studies, arguing that the use of gender-neutral language and lack of gender analysis in political discourse tend to downplay the well-known association between poverty and female-led households.

The paper examines household income, assets and debts in Canada compared to the other liberal states, focusing on gender differences and lone-mother households. It shows that Canada compares unfavourably with most of the other liberal states, with the exception of the United States. Although Canada has relatively high maternal employment rates, it also has higher poverty rates than Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, which still provide payments for care at home (mainly for lone mothers with young children). Canada has also been less successful than Australia and New Zealand in reducing the gender wage gap. Furthermore, Canadian social spending on families was the lowest of the five liberal states in 2003 (OECD, Babies and Bosses). The paper argues that before ‘child’ poverty can be reduced, Canadian policy makers need to acknowledge more openly its gendered aspects and the difficulties many lone mothers face when trying to work their way out of poverty.

Before examining gender patterns of work, it is important to outline the changing context of labour markets and social policy restructuring.

Restructuring and Neo-liberal Reforms

In recent decades, labour markets have become more global and internationally competitive as governments sign new trade agreements that permit entrepreneurs to move their businesses and capital more freely throughout the world. Employers have also maintained commercial competitiveness by extending production or service hours, replacing some employees with new technologies, and increasing the number of temporary staff on their payroll. Employing casual staff sometimes enables employers to avoid paying certain fringe benefits, to downsize their labour force during hard times, and reduce union obligations (Baker, Restructuring Family).

Freer trade, new technologies and variations in international labour costs have edged some industries and workers out of the market but have allowed others to prosper (Torjman and Battle). Some manufacturing jobs that were previously unionized and nationally based have shifted outside the borders of Western economies and lost both their legislative and trade union protections. The service sector of the labour force has also expanded in Canada and the other liberal states, providing more new positions, jobs that are temporary and part-time rather than full-time year-round (Banting and Beach; Van den Berg and Smucker).

Much of the concern from the political left about global markets relates to the neo-liberal ideologies and practices that usually accompany global trade and multilateral agreements. Neo-liberals generally argue that the Keynesian welfare state involved too much state intervention and that instead of maintaining expensive income support programs, the state should deregulate the labour market, become less involved in economic activities, and reduce income taxes. Neo-liberals often assume that families are autonomous economic units responsible for their own survival, that jobs rather than state income support provide the best income security, that individuals make rational decisions to maximize their earnings, and that all workers are equally able to relocate for work-related reasons. They also believe that many social services can be provided more effectively by the private sector than by the state. These beliefs and practices have recently influenced state restructuring and social programs in all liberal states (Baker, Restructuring Family).

A number of researchers have argued that neo-liberal restructuring has transformed social policy and services in many countries, and disproportionately affected female workers who have been expected to absorb much of the cost of restructuring (Neysmith and Chen). McDaniel noted that restructuring often involves decentralization, which tends to shift responsibilities to communities and families, all under the guise of democratic accountability. As more states privatize caring activities for children, persons with disabilities and the frail elderly, women are expected to perform more unpaid caring work within their families. When this work is unpaid, it becomes further devalued. Briar-Lawson et al. concluded that globalization and neo-liberal reforms lead to growing inequality and impermanent work, augment national debt, contribute to urbanization, fragment extended families and reduce children’s aspirations as they realize that education does not automatically translate into employment.

Despite these socio-economic transformations, household incomes in Canada and the other liberal states have been maintained and, in some cases, increased by the rising employment rates of wives. Household assets have generally increased among higher income households with fewer restrictions on credit and the recent housing boom (VIF; Jenkins; Girouard et al.; Sauvé). However, the gap between high- and low-income households has also been growing, attributed to factors such as market conditions that pay some workers high wages while encouraging temporary or part-time jobs and low minimum wages for others. The gap between the rich and the poor has also been influenced by rising rates of marital separation and welfare restructuring (OECD, Society at a Glance). Couples with two full-time incomes, higher education and no children tend to have the highest incomes, while large ‘visible minority’ families, beneficiaries and lone-mother households tend to experience lower incomes and higher levels of household debt (Warner-Smith et al.).

The next section examines gendered employment patterns, before discussing household debt and the consequences of marital separation on employment and assets.

Gendered Employment Outcomes

Canadian governments have typically seen parental employment as the main solution to child poverty (Baker and Tippin, Poverty), yet they have not always openly acknowledged that patterns of work continue to be ‘gendered’ or that employed people cannot always escape poverty. Although employment population ratios for women have increased rapidly over the last decade as shown in Table 1, in Canada and in the other liberal states surveyed, male employment remains consistently higher. Similarly, men’s unemployment rates are higher than women’s in most of these countries. It is also interesting to note that in 2007, Canada had both the highest female employment and unemployment rates of the liberal states. With the current recession, Canadian unemployment rates have already increased by 2.4% between June 2008 and June 2009 (Statistics Canada), which will undoubtedly translate into a rise in ‘child poverty’ rates.

Table 1

Employment/Population Ratios and Unemployment Rates of Males and Females Aged 15-64 in the Liberal Welfare States, 1994 and 2007

In Canada and the other liberal states, occupational segregation by gender has been declining in the workforce but men are still more likely than women to occupy lucrative managerial and professional positions. Men also tend to work longer hours for pay while more women work part-time or opt out of paid work, especially during early motherhood (OECD, Society at a Glance 53). Parenthood and children’s ages interact with gender to influence the earning patterns of men and women (Beaujot; Zhang). In the liberal states surveyed, mothers with preschool children are less likely to be employed than fathers, childless women, or mothers with older children. Furthermore, the more children women have, the less likely they are to be employed full-time while fathers with many children tend to work full-time or overtime (OECD, Society at a Glance 57). Table 2 portrays the percentage of men and women working part-time by presence of children, showing lower rates of part-time work in Canada for all women and for mothers, compared to Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Table 2

Percentage of Persons Aged 25-54 with and without children, 2000 Working Part-Time by Sex and Presence of Children, 2000

In Canada and the other liberal states, a gender gap is apparent in hourly earnings, persisting for full-time employees and all workers, and men’s jobs tend to remunerated at a higher rate regardless of qualifications or skills required (Kingfisher; Daly and Rake). Although this gender gap has declined since 1980 in most OECD countries (OECD, Growing Unequal? 81), Table 3 shows that in 2006, it stood at 21% in Canada, significantly higher than in Australia and New Zealand, even higher than in the United States. Both Australia and New Zealand have legacies of higher rates of unionization and centralized wage bargaining, although labour relations have changed substantially in the past two decades (Castles and Shirley). Table 3 also shows that the incidence of low pay is the second highest in Canada (second to the United States) where it has remained stable since 1996. In all the liberal states listed, women are much more likely than men to work in low-paid jobs, although this is not shown in this table.

Table 3

The Change in the Gender Wage Gap[*] and the Incidence of Low Pay[**]

The gender wage gap refers to the difference between the median earnings of men and women relative to median earnings of men.

The incidence of low pay refers to the percentage of workers earning less than 2/3 of median earnings.

Employed parents with young children cannot retain their jobs without some form of childcare. Although mothers used to enable fathers’ employment by caring for their children at home, more mothers are now employed in Canada and the other liberal states. Research has found that reducing childcare costs increases maternal employment (Christopher; Roy), but the various countries focus their childcare support on different household types. For example, the Canadian federal government offers a more substantial income tax deduction than the other countries for the childcare expenses of employed parents which tends to help middle-income parents more than those with lower incomes. Although childcare subsidies vary by province, the OECD nevertheless compiles composite figures of childcare costs by country. As Table 4 indicates, the costs for lone parents with two children and average earnings have represented 27% of their earnings in Canada, compared to 42% in New Zealand and only 9% in the United Kingdom (OECD, Society at a Glance 59).

Table 4

Childcare Costs as % of Net Income for Working Couples and Lone Parents

All five countries (or jurisdictions within them) have recently reduced specific childcare costs to enhance the employability of mothers. For example, Quebec now heavily subsidises childcare for all parents, regardless of employment status; parents pay a maximum of $7.00 per day (Albanese). Maternal employment rates increased in Quebec following the introduction policy and fell in Alberta when subsidized childcare spaces were reduced during the same period, indicating that lack of affordable childcare is an impediment to maternal employment (Roy). In Canada, and especially in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, providing more generous childcare subsidies to a broader category of care providers or parents has recently become an election issue.

Despite changing employment patterns over the decades, the financial contribution of women to their household continue to be reduced by lower employment rates than men, shorter working hours, lower pay, and high childcare costs relative to earnings in Canada and the other liberal states. In fact, women tend to earn less than their male partners, who are often older and work longer hours (Beaujot). If women live with partners who earn adequate wages, their lower earnings may be less consequential to household finances although these may alter spousal power relations within heterosexual couples (Potuchek; Baker, Choices and Constraints). The financial consequences of lower female income are particularly apparent when mothers raise children without a partner in the household.

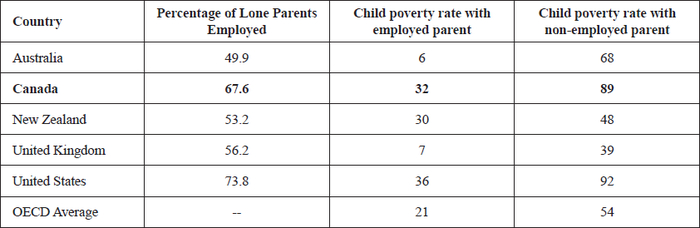

While the employment rates of lone parents (who are mainly mothers) have increased over the past decades, they continue to vary by country; (as Table 5 indicates) two-thirds of lone parents are employed in Canada, one half in Australia, and three-quarters in the United States. This table also reveals that having a job does not mean that one-parent households are always above the poverty line. When children live with an employed lone parent, 32% still live in poverty in Canada compared to 6% in Australia (where the gender pay gap is smaller) and 36% in the United States (where the incidence of low pay is higher).

When lone parents are not employed (usually living on social benefits), a much higher percentage of children live in poverty—89% in Canada as compared to 39% in the United Kingdom and 92% in the United States. Poverty rates for one-parent households are much lower in the United Kingdom and New Zealand than in Canada, suggesting that cross-national variations exist in the levels of state income support, tax benefits and wages, as well as the pressures and opportunities to become self-supporting. Despite public policies to encourage lone parents into paid work, countries like Canada (and the United States), with the highest employment rates for lone parents, also have the highest child poverty rate for one-parent households, as Table 5 indicates.

Table 5

Employment and Poverty Rates in One-Parent Households

Household Assets and Home Ownership

Examining income figures gives only a partial picture of the economic circumstances of households with children. Families generally accumulate most of their assets through home ownership, but home ownership rates have declined over the past thirty years in Canada (and New Zealand) to about 68% of households, while remaining stable in Australia at about 70% (NZHRC; VIF 117; Reserve Bank of Australia). Home ownership rates tend to rise with age and relationship formation, being higher for married couples than for cohabiting or separated people (Baxter & McDonald).

Canadian figures indicate that of the fifth richest households, 91% own their own home compared to 37% of the poorest households (VIF 117). Furthermore, home ownership rates are gendered and vary by age, marital status and household composition. The rate of home ownership is 88% for elderly couples, 48% for sole-mother households, and 44% for the unattached elderly (who are mainly women). Women without male breadwinners or retired earners are particularly disadvantaged in the housing market (VIF 117) but home ownership rates could decline further with more cohabitation, separation and repartnering, combined with increased job insecurity.

During the recent housing boom, more Canadian families were unable to find affordable housing, especially those with more than three children, new immigrants or mother-led families (VIF). Low-income families are more likely to live in rental accommodation and pay market rents in the liberal welfare states surveyed than in state housing (Baker, Restructuring Family). Reliance on private housing means that many households with children are forced to live in unhealthy, overcrowded and unsafe accommodation, which results in an increase of respiratory ailments, the spread of infectious diseases, depression and anti-social behaviour (Jackson & Roberts).

While the assets of two-earner households tend to be greater, the assets of non-employed women are sometimes enhanced by transfers from their partner. Widows are more likely than widowers to inherit assets from deceased partners as wives tend to outlive their husbands (who are usually older). Wives’ assets have also increased since marriage partners are required to share ‘family assets’. In Canada and the other liberal states, none of this translates into heterosexual women having equal access to household money during marriage or after separation. Even when shared earnings are held in joint accounts, husbands have greater control over them, as well as more access to credit (Pahl, Couples; Individualisation).

Despite the emphasis on rational decision making in financial transactions, discussions of household money often involve strong emotions. Singh differentiated between ‘marriage money’ which is domestic and co-operative and typically held in a joint account, and ‘market money’ which is impersonal and subject to contract. The difference between the two is particularly important if couples divorce or use their family home as collateral for a husband’s business loan. When the divorce settlement is finalized or the bank demands repayment, the financial arrangements that had represented on trust and love suddenly become impersonal and contractual (Pahl, Couples). Lawton uses the concept of ‘sexually-transmitted debt’ (7) to discuss the ways that financial co-operation within marriage can result in serious problems once trust is broken or the relationship sours.

Household Debt

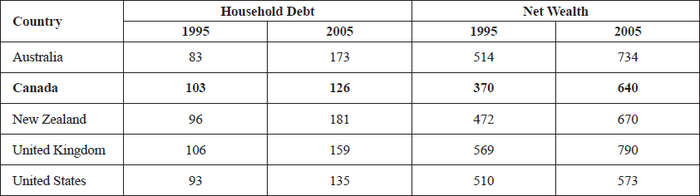

Since the 1990s, levels of household debt have increased, reaching more than 126% of household income in Canada in 2005 with even higher levels in other liberal welfare states, as shown in Table 6 (Girouard et al. 9). Most of this debt comes from mortgages and the rising levels of debt have been influenced by past buoyant housing markets. Table 6 also shows wealth for the five countries listed has also increased in the past decade with Canada in fourth place. However, non-mortgage debt (including car loans, credit card debt, and unpaid rent or utility bills) also rose, and is particularly high among younger people (Girouard et al. 19). Rising material aspirations, lower inflation rates, financial deregulation, higher house prices and easier access to credit have all contributed to mounting household debt (Legge & Heynes).

Table 6

Household Debt and Net Wealth as % of Annual Disposable Income, 1995 and 2005

Mortgage debt is usually less detrimental than non-mortgage debt because most home owners gradually repay their mortgages over the years while their incomes rise and the value of their dwelling increases. Home owners are less likely than tenants to experience debt problems and are five times less likely to fall behind in their mortgage payments than tenants are to default on their rent (DWP & DTI). Debt problems which are often (but not always) related to low household income, often result from sudden income losses such as redundancy, overuse of credit or loss of one household earner (Balmer et al.).

Research has differentiated between chronic indebtedness (experienced by the young, single and persons unable to control expenditures) and temporary indebtedness influenced by sudden changes in circumstances (Balmer et al.). These circumstances could relate to ill health, accidents, unemployment, civil justice problems, or marriage breakdown, and people who fall into serious debt often experience multiple problems making recovery difficult. Researchers define the quintessential ‘problem debtor’ as a young single parent living in rental accommodation. Research has found that one in three lone parents falls into arrears (Edwards; Balmer et al.). It has also been shown that divorced people are more likely than married couples to fall into arrears and to experience diminished access to credit (Lyons and Fisher). What is it about marital separation that so often leads to low income and assets in all the liberal states surveyed?

Separation, Debt and Poverty

In Canada and the other liberal states, separation and divorce rates have increased since the 1970s, and over three-quarters of children from divorced parents live with their mothers (Baker, Lingering Concerns). In addition, more couples are cohabiting without being legally married. While cohabiters tend to be younger and have fewer children, they have higher separation rates than married couples and parents with more children (Bradbury & Norris; Qu & Weston). This suggests more relationship instability in the future.

In Canada and the other liberal states, separating partners are usually required to divide their ‘family assets’ equally, unless, for some reason, this would be deemed unfair. Parties are permitted to retain any personal inheritance and business assets. However, as more people become self-employed, disputes arise about whether assets belong to the business or family. Former wives are no longer awarded life-long spousal support as they were in the liberal states before the 1970s. Today, they may be granted temporary support based on need, but spousal support was ordered in only 10% of divorce cases in Canada in 2004 (VIF 37). Separated partners are usually expected to support themselves and parents are required to support their children regardless of their living arrangements. It should also be noted that many couples in the process of separation have few assets and considerable debt.

All the Canadian provinces and territories, which design and administer their own child support schemes, have tightened enforcement procedures since the 1980s, as have the other liberal states surveyed (Baker, Choices and Constraints). However, unlike Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, awards in Canada are still are set by provincial court judges based on national guidelines established in 1997 and amended in 2002. The end result is that the amount of child support awarded tends to vary from one province to the other.

Although child support legislation is gender neutral, support is typically expected to be paid by the non-resident parent, usually the father. Canadian research indicates that in 2004 fathers were ordered to pay child support in 93 per cent of cases, with a median payment of $435 per month (vif 37). Guidelines, usually based on the non-resident parent’s income rather than net assets, do not always consider the children’s financial needs (Wu and Schimmele). Furthermore, enforcement is clearly a problem, especially in the case of couples that never married or cohabited, or where the father is unemployed or in debt (Boyd; Smyth).

While default rates have decreased with the new enforcement systems, 65 per cent of support cases in Canada are in arrears, which means that the amount was not totally paid, not paid on time, or not paid at all (Martin and Robinson). The minimum child support payment required by the state is usually kept at a low level, to encourage and enable low-income fathers to pay, but this means that it is insufficient to cover the cost of raising the child. Unfortunately, about one third of fathers lose contact with their children altogether (Smyth). In Canada and the other liberal states, the majority of divorced or separated men repartner and some produce additional children with new partners resulting in many fathers not being able to support two households with children.

Debates about child suppport partially reflect perceptions of gendered disparities in child-rearing responsibilities, access to children, living situations and post-separation incomes. A Canadian study of the circumstances of recently divorced or separated mothers and fathers[2] found that 66% of lone parents are women and only 30% are men (Lochhead and Tipper). One quarter of the fathers live alone compared to only 6% of mothers. More fathers than mothers have either returned to live either with their own parents or move in with a new partner, with or without children. Educational qualifications of separated parents were comparable and women’s employment rates were relatively high but their personal incomes were much lower than men’s. For example, in 2006, 44% of mothers and only 19% of fathers earned less than $30,000 per year, while 37% of fathers and 11% of mothers had incomes greater than $60,000. The study also found that household incomes, which could include income from new and former partners, are more equitable but substantial gender differences remain.

In Canada and the other liberal states, lone mothers relying on welfare payments are often unable to protect their children from poverty because family problems interfere with paid work and loan repayments (Whitehead et al.; Cook et al.; Baker, Child Poverty; Worth & Macmillan; Balmer et al.). Poverty, family conflicts and unsafe communities sometimes dominate the lives of lone mothers driving them to focus on short-term goals. Consequently, their exposure to violence, disrespect, depression and health-related setbacks increases. Neither the welfare nor the public health systems adequately address the mental and physical health issues of many sole mothers who are expected to exit from welfare.

In research projects, lone mothers report that they are indebted to banks, finance companies, landlords, relatives, friends, family doctors, pharmacists and even the welfare office, while being owed money by former partners, relatives and tenants (Edin and Lein; Baker, Child Poverty). A poor credit history affects women’s ability to get a job, rent or buy a home, or purchase a vehicle (Lyons and Fisher). While welfare payments significantly reduce the probability of debt default for divorced women, child support has little impact on default rates (Lyons and Fisher), probably because the amounts are typically too low.

Lone mothers often employ creative strategies to manage debt, including postponing expenses (such as visiting the doctor), going without food so the children can eat, ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’, dealing in the ‘grey market’, working without reporting income to the welfare or tax offices, and sharing accommodation (Edin and Lein; Hunsley; Tippin and Baker). Hunsley found in his Canadian comparative study, that lone mothers relying on income support were more likely to improve their economic status through marriage than through paid work. However, cohabitation or marriage is only beneficial to lone mothers if the new partner has a steady job, shares his earnings, is debt free, is a loving partner, and assists with childrearing (Edin and Kafelas).

The strategies available to lone mothers to deal with financial problems are often limited by their lack of socio-cultural resources, which can lead to regrettable choices. Earning capacity is often challenged by the lack of affordable and reliable childcare, transportation problems, unpredictable and harmful relationships with former male partners, as well as children’s health issues. These problems can also interfere with their ability to find jobs or suitable new partners who can help them out of debt. The social welfare system may view low income, poor health, childcare problems, and lack of paid work as discrete policy issues but beneficiary mothers know from experience that they are related (Baker and Tippin, When Flexibility; More Than Just).

Government Policies to Reduce Child Poverty

Since the 1990s, the liberal welfare states have all reformed their child benefit programs, childcare provisions, and other social services for families with children, using the discourse of ‘fighting child poverty’ and ‘taking children off welfare’ (Baker, Restructuring Family). Canadian governments have been talking about ‘investing in children’, a relatively new policy paradigm that enhances child benefits and subsidies for public childcare services, promotes children advocacy, and provides more effective child protection services (Jenson). However, provinces with neo-liberal governments (especially Ontario and Alberta) have been less likely to adopt this discourse and have been reluctant to reform their early childhood education and childcare policies (Jenson).

Governments have been pressured to reform family-related policies by different national and international interest groups, including the Child Poverty Action group which also operates in countries like New Zealand and the United Kingdom. New socio-economic challenges have also confronted policy makers, such as the growing gap between the rich and the poor aggravated by neo-liberal labour markets, and problems related to work/ family balance in a world where more mothers are employed and more households are led by mothers (Taylor-Gooby). Government policies have also been influenced by pressure from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the findings of studies such as the Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth and other comparative research (Jenson).

At the same time, Canada and the other liberal states have reduced certain types of family support (Baker, Restructuring Family). Before 1990, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom provided universal child allowances for all parents with children, as well as income tax deductions for taxpayers and their ‘dependents’. The United States has never offered parents a universal family allowance scheme although it has offered tax benefits to families. Now, the United Kingdom is the only liberal state that continues to pay universal child benefits designed to promote ‘horizontal equity’ between households with children and adults without dependents (Baker, Restructuring Family). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Canada, Australia and New Zealand replaced their universal child allowances with targeted child tax benefits occasionally raising the value of the benefits since. Canada and Australia now target child benefits to moderate- and low-income families, while New Zealand directs this payment only to low-income families. Behind such targeting is the neo-liberal idea that scarce public money should be used to resolve ‘child poverty’ rather than to support ‘rich’ parents (Baker & Tippin, Poverty).

Canada and New Zealand have also introduced the controversial policy of tying the level of children’s benefits to parents’ employment status and to their income (Baker, Restructuring Family). Allocating child benefits to parents who earn moderate or low incomes saves public money while conveying the message that governments expect parents to support their children through paid work. However, children’s needs do not depend on their parents’ earning activities. Paying a lower child benefit to parents receiving social benefits has been viewed as unjustifiable by lobbyists such as the Child Poverty Action Group, because these households have the lowest incomes.

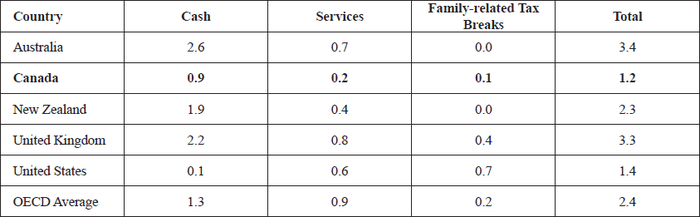

Although Canada and several other governments have increased the level of child benefits for some families, the cost of living and especially accommodation costs have also been rising. The level of child benefits in Canada and in the other countries surveyed is not indexed to the consumer price index (as are old age benefits in Canada and New Zealand), and targeting child benefits has reduced entitlement especially for New Zealand families. Table 7 shows how Canada and the other liberal states apportion their spending on families, revealing that Canada had the lowest level of social spending in 2003 — even lower than the United States. Australia and the United Kingdom on the other hand provide much higher levels of support for families with children. Both countries permit lone mothers to care for their children at home for longer periods than do Canadian provinces, allow lone mothers to work part-time while receiving partial income support, and tax the earnings at a lower rate (Whiteford).

Table 7

Social Spending on Families[*] as % of Gross Domestic Product, 2003

Includes child payments and allowances, parental leave benefits and childcare support.

In recent years, Canada and the other liberal states have limited the periods of eligibility for unemployment benefits as well and for welfare payments to individuals and parents with school-aged children (Baker and Tippin, Poverty). Although Canadian unemployment benefits are delivered by the federal government, and are therefore uniform across the country, welfare payments are provided by the provinces. A review of the total welfare income for a lone parent with one child reveals important disparities: in Alberta it represents 65% of the amount considered as the poverty line (using the absolute measure of the market basket of goods) compared to 100% in Quebec and 102% in Newfoundland (Sauvé). However, welfare cuts have been even more extreme in the United States where limits are placed on the number of years that mother-led households can receive welfare payments (Mink, Welfare’s End; Violating Women). Yet many of these households living in poverty are trying to repay their debts.

Policies to address problem debt tend to focus on counselling which would suggest that falling into debt is merely the result of personal decision making (Balmer et al.). Such policy ‘solutions’ tend to overlook the underlying economics of poverty and social exclusion, the politics of restructuring, and the gendered dimensions of earning. Growing social inequality, cuts to state income support, shortages of social housing, rising health care expenses, gender wage gap, combined with the expansion of low-paid work all contribute to a problem that cannot be easily resolved through advice and counselling alone. Living in poverty and carrying serious debts also increases stress levels and contributes to poor health, disability, and early mortality (Edin & Lein; Legge & Heynes).

Canada has promoted paid work as the main solution to family poverty but has given less attention than Australia, for example, to ensuring that minimum wages match living costs and that income support enables low-income mothers to avoid poverty. In recent years, Canada and the liberal states have also shifted focus away from the need to enforce pay equity for women, to deal with rising levels of household debt, and to provide social housing for the growing number of low-income families who cannot afford market rents. In contrast, some European countries such as Sweden, Finland and Belgium have made considerable public investments in health and social services for families, including universal child benefits, family-related employment leave, heavily subsidized childcare services, social housing for low-income families, and other forms of income support (Gauthier; UNICEF; Hantrais).

Conclusion

Canadian welfare policy and political discourse have focused on parental employment as the main solution to child poverty. However, this paper shows that the poorest Canadian families are led by lone mothers, and that being a woman and mother without a male breadwinner contributes to household poverty in a world where women’s employment is lower paid and where their heavier unpaid workload but often goes unacknowledged. In addition, labour markets have been rapidly changing, providing fewer long-term secure jobs forcing more family members to seek employment and others to work longer hours to make ends meet. Employment may be one of the answers to family poverty and household debt, but this is only true when job markets are booming and wages match living costs, which is no longer the situation.

Since the 1980s, Canada has focused on economic reforms, freer trade, and labour market deregulation, responding to strong pressure from business-related interest groups. Politicians have continued to emphasize the importance of increasing productivity, improving national competitiveness in global markets, and developing a skilled workforce. Income support remains a ‘safety net’ but benefits have been restructured so that fewer households are receiving this assistance. At the same time, public discourse continues to stress the importance of ‘good parenting’, to view children as a ‘future resource’, and to urge parents to earn their way out of poverty.

In Canada as well as in the other liberal states, many employers have minimized payroll costs by hiring part-time or casual workers. These jobs may enable mothers to cope with domestic responsibilities but seldom pay enough to support entire families. Full-time and high-paying jobs are harder to find and unemployment rates are once again rising while income support programs continue to provide minimal benefits in some Canadian provinces. Governments have heightened public expectations that former beneficiaries can earn their way out of poverty without recognizing that the transition from welfare to employment can be risky as parents are forced to forfeit income security and services (Baker, Restructuring Family).

OECD statistics show that mothers with paid jobs have higher income than those receiving social benefits in Canada and all the other liberal states (OECD, Employment Outlook). Many beneficiary mothers are also highly motivated to become self-supporting to improve their incomes, expand their social networks, and provide positive role models for their children. However, employment is most likely to reduce family poverty when workers are healthy and well-qualified, when high quality childcare is available and affordable, and where employees are free to relocate to find the best jobs. However, studies show that lone mothers and their children often suffer from poor health, some mothers have limited job qualifications, and many find childcare services inconvenient and unaffordable. In addition, lone mothers with access agreements with the children’s father may not be free to relocate to accept new jobs.

The willingness of Canadian provinces to provide long-term income support for mothering at home has now dwindled, and time-limited ‘welfare’ has become widespread in North America (Bashevkin, Welfare Hot Buttons; Women’s Work; Baker, Restructuring Family). However, the promotion of maternal employment has been resisted in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom because although paid work may improve income and social networks, it often results in insecurity, requires complicated childcare arrangements, elevates stress levels, and introduces time management problems (Baker, Devaluing Mothering). The fact remains that without improved income support and affordable childcare services, many mothers are unable to work their way out of poverty.

Cross-national research indicates that some governments (especially in Nordic countries) regulate wages and working conditions, develop tax systems and government transfers to stabilize and supplement earnings, and keep poverty rates low for families with children (Hantrais; UNICEF; Baker, Restructuring Family). However, Canada continues to focus on moving beneficiaries into low-paid jobs, enforcing child support, providing modest child benefits, and keeping welfare payments relatively low over shorter periods.

As the recession deepens, Canadian governments need to acknowledge the gendered patterns of paid and unpaid work that have persisted for decades. Infrastructure development is emerging as a popular policy option for many governments to reduce unemployment but this option is inherently biased towards male employment if it concentrates mainly on construction. Job creation also needs to be bolstered in occupations with large numbers of women workers, such as education, social services and health care. In addition, more mothers need to be offered the necessary social support to enable them to maintain their paid and unpaid work.

Using the concept of ‘child poverty’ tends to downplay the fact that poverty rates for households with children are related to adult employment conditions as well as the generosity of state income support. Furthermore, gender, marital separation, and the daily responsibility for young children influence access to income and assets. Most one-parent households, which have the highest child poverty rates, are led by mothers who have lower employment rates than fathers, receive lower pay when they are employed, and are sometimes deeply in debt. In addition, these mothers feel that they must work fewer hours for pay in order to meet their caring responsibilities at home. This paper suggests that as the economic recession deepens, policy makers could benefit from gendering their analysis before creating new poverty reduction programs. In fact, Canadian governments could learn some lessons from Australia and the United Kingdom.

Appendices

Notes

Bibliographie

- Albanese, Patrizia. “Small town, big benefits: The ripple effect of $7/day childcare.” The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 43.2 (2006): 125-140. Print.

- Baker, M. “Child Poverty, Maternal Health and Social Benefits.” Current Sociology 50.6 (2002): 827-842. Print.

- Baker, M. “Devaluing Mothering at Home: Welfare Restructuring and Perceptions of “Motherwork”.”, Atlantis: A Women’s Studies Journal 28.2 (2004): 51-60. Print.

- Baker, M. Restructuring Family Policies: Convergences and Divergences. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

- Baker, M. Choices and Constraints in Family Life. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2007a.

- Baker, M. “Managing the Risk of Poverty: Changing Interventions by the State.” Women’s Health and Urban Life VI 2 (2007b): 8-21. Print.

- Baker, M. “Lingering Concerns About Child Custody and Support.” Policy Quarterly 4.1 (2008): 10-17. Print.

- Baker, M. and Tippin. Poverty, Social Assistance and the Employability of Mothers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

- Baker, M. and Tippin “When Flexibility Meets Rigidity: Sole Mothers’ Experience in the Transition from Welfare to Work.” Journal of Sociology 38.4 (2002): 345–60. Print.

- Baker, M. and Tippin “More Than Just Another Obstacle: Health, Domestic Purposes Beneficiaries, and the Transition to Paid Work.” Social Policy Journal of New Zealand Issue 21 (2004): 98-120. Print.

- Balmer, Nigel, Pascoe Pleasance, Alexy Buck and Heather C. Walker. “Worried Sick: the Experience of Debt problems and their Relationship with Health, Illness and Disability.” Social Policy and Society 5.1 (2005): 39-51. Print.

- Banting, Keith G. and Charles M. Beach, eds.. Labour Market Polarization and Social Policy Reform. Kingston, Ontario: Queen’s University, School of Policy Studies, 1995.

- Bashevkin, Sylvia. Welfare Hot Buttons: Women, Work, and Social Policy Reform. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002a.

- Bashevkin, Sylvia. ed.. Women’s Work is Never Done: Comparative Studies in Care-Giving, Employment, and Social Policy Reform. New York: Routledge, 2002b.

- Baxter, Jennifer and Peter McDonald. “Home Ownership among Young People in Australia: In Decline or Just Delayed?” University of Queensland, June, (2004): 29-30. Conference paper prepared for NLC Workshop.

- Beaujot, Roderic. Earning and Caring in Canadian Families. Peterborough, Ontario: The Broadview Press, 2000.

- Boyd, Susan B. Child Custody, Law, and Women’s Work. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Bradbury, Bruce, and Kate Norris. “Income and Separation.” Journal of Sociology 41.4 (2005): 425–46. Print.

- Briar-Lawson, Katherine; Hal Lawson, Charles Hennon and Alan Jones. Family-Centred Policies and Practices: International Implications. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- Castles, Francis G. and Ian F. Shirley. “Labour and Social Policy: Gravediggers or Refurbishers of the Welfare State?” In The Great Experiment: Labour Parties and Public Policy Transformation in Australia, and New Zealand. (Edited by F. Castles, R. Gerritsen and J. Vowles). Auckland: Auckland University Press (1996): 88-106.

- Christopher, Karen. “Welfare State Regimes and Mothers’ Poverty.” Social Politics 9.1 (2002): 60-86. Print.

- Cook, Kay, Kim Raine & Deanna Williamson. “The Health Implications of Working for Welfare Benefits: The Experiences of Single Mothers in Alberta, Canada.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 11.1 (2001): 20-26. Print.

- Daly, M. and K. Rake. Gender and the Welfare State. Cambridge: Polity, 2003.

- DWP and DTI (Department of Work and Pensions and Department of Trade and Industry). Tackling Over-Indebtedness, Action Plan 2004. London: DWP and DTI, 2004.

- Edin, Kathryn and Laura Lein. Making Ends Meet: How Single Mothers Survive Welfare and Low-Wage Work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997.

- Edin, Kathryn and Maria J. Kefalas. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Edwards, S. In Too Deep. CAB Clients’ Experience of Debt. UK: Citizen’s Advice Bureau, 2003.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990.

- Gauthier, Anne Hélène. The State and the Family: A Comparative Analysis of Family Policies in Industrialized Countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Girouard, Nathalie, Mike Kennedy and Christophe André. “Has the Rise in Debt Made Households More Vulnerable?” OECD Working Paper #535 (2006). Print.

- Hantrais, Linda. Family Policy Matters: Responding to Family Change in Europe. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2004.

- Hunsley, Terrance. Lone Parent Incomes and Social Policy Outcomes. Canada in International Perspective. Kingston, Ontario: School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University, 1997.

- Jackson, A. and P. Roberts. “Physical Housing Conditions and the Well-Being of Children.” Background Paper on housing for The Progress of Canada’s Children 2001. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development, 2001. Print.

- Jackson, Andrew, and Matthew Sanger. When Worlds Collide: The Implication of International Trade and Investment Agreements for Non-Profit Social Services. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development, 2003.

- Jenkins, Stephen P. “Marital Splits and Income Changes Over the Longer Term.” Paper #2008-07. University of Essex: Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2008. Print.

- Jenson, Jane. “Changing the Paradigm: Family Responsibility or Investing in Children.”, Canadian Journal of Sociology 29.22 (2004): 169-192. Print.

- Kingfisher, Catherine. Ed. Western Welfare in Decline: Globalization and Women’s Poverty. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Lapointe, Rita Eva and C. James Richardson. Evaluation of the New Brunswick Family Support Orders Service. Fredericton: New Brunswick Department of Justice, 1994.

- Lawton, J. “What is Sexually-Transmitted Debt?” Women and Credit: A Forum on Sexually-Transmitted Debt. Ed. (R. Meikle). Melbourne: Ministry of Consumer Affairs, 1991. Print.

- Legge, Jaime and Anne Heynes. Beyond Reasonable Debt. Wellington, New Zealand: Families Commission and Retirement Commission Report, 2008.

- Lochhead, Clarence and Jenni Tipper. “A Profile of Recently Divorced or Separated Mothers and Fathers.” Transition (Vanier Institute of the Family). 38.3 (2008): 7-10. Print.

- Lyons, Angela C. and Jonathan Fisher. “Gender Differences in Debt Repayment Problems After Divorce.” The Journal of Consumer Affairs. 40.2 (2006): 324-346. Print.

- Martin, Chantal and Paul Robinson. “Child and Spousal Support: Maintenance enforcement Survey Statistics, 2006/2007.” Statistics Canada catalogue #85-228-XIE. Ottawa: Ministry of Industry, 2008. Print.

- McDaniel, Susan A. “Women’s Changing Relations to the State and Citizenship: Caring and Intergenerational Relations in Globalizing Western Democracies.” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 39.2 (2002): 125-150. Print.

- Mink, Gwendolyn. Welfare’s End. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

- Mink, Gwendolyn. “Violating Women: Rights Abuses in the American Welfare Police State.” Women’s Work is Never Done. Ed. (S. Bashevkin). New York: Routledge, 2002. 141-164. Print.

- NZHRC (New Zealand Housing Research Centre). “Homeownership in New Zealand.” University of Otago. N/a. <www.otago.ac.nz>.

- Neysmith, Sheila, and Xiaobei Chen. “Understanding How Globalisation and Restructuring Affect Women’s Lives: Implications for Comparative Policy Analysis.” International Journal of Social Welfare 11.3 (2002): 243-253. Print.

- O’Connor, J.S., A.S. Orloff and S. Shaver. States, Markets, Families: Gender Liberalism and Social Policy in Australia, Canada, Great Britain and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). OECD Employment Outlook July 2002. Paris: OECD, 2002.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Society at a Glance: OECD Social Indicators 2005. Paris: OECD, 2005.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). “Babies and Bosses: Reconciling Work and Family Life (Volume 5): A Synthesis of findings for OECD Countries.” OECD. 2007a. <www/oecd.org/els/social/family>

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Society at a Glance: OECD Social Indicators 2006. Paris: OECD, 2007b.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Employment Outlook 2008. Paris: OECD, 2008a.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Growing Unequal? : Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD, 2008b.

- Pahl, J. “Couples and Their Money: Theory and Practice in Personal Finances.” Social Policy Review 13. Ed. (R. Sykes, C. Bochel and N. Ellison). Policy Press. 2001. 17-37. Print.

- Pahl, J. “Individualisation in Couple Finances: Who Pays for the Children?” Social Policy and Society 4.4 (2005): 381-391. Print.

- Potuchek, J.L. Who Supports the Family: Gender and Breadwinning in Dual- Earner Marriages. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997.

- Qu, Lixia and Ruth Weston. “Snapshot of Family Relationships.” Family Matters May (2008). Print.

- Reserve Bank of Australia. “Household Debt: What the Data Show”, Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, March (2003): 1-11. Print.

- Richardson, C. James. “Divorce and Remarriage.” Families: Changing Trends in Canada 4th edition. Ed. (M. Baker). Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson. 2001. 206–37. Print.

- Roy, Francine. “From she to she: changing patterns of women in the Canadian labour force.” Canadian Economic Observer (Statistics Canada) 19.6 (2006). Print.

- Saunders, Peter. “The Towards New Indicators of Disadvantage Project, Bulletin #1. Identifying the Essentials of Life.” Social Policy Research Centre Newsletter No. 94 (2006). Print.

- Sauvé, Roger. “The Current State of Canadian Family Finances, 2008 Report.” Vanier Institute of the Family. 2009. <www.vifamily.ca>

- Singh, S. Marriage Money: The Social Shaping of Money in Marriage and Banking. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1997.

- Smyth, Bruce. Ed. Parent-Child Contact and Post-Separation Parenting Arrangements. Research Report #9. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2004.

- Statistics Canada. “Labour Force Characteristics, Seasonally Adjusted, By Province.” Statistics Canada. 2009. July 2010. <www.statcan.gc.ca>

- Taylor-Gooby, Peter. Ed. New Risks, New Welfare. The Transformation of the European Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Tippin, David and Maureen Baker. “Managing the Health of the Poor: Contradictions in Welfare-to-Work Programs.” Just Policy, 28.December (2002): 33-41. Print.

- Torjman, Sherri and Ken Battle. Good Work. Getting It and Keeping It. Toronto: Caledon Institute of Social Policy, 1999.

- UNICEF. Child Poverty in Rich Nations. Florence: Innocenti Research Centre, 2005.

- Van den Berg, Axel, and Joseph Smucker. Eds. The Sociology of Labour Markets. Efficiency, Equity, Security. Toronto: Prentice Hall Allyn and Bacon Canada, 1997.

- VIF (Vanier Institute of the Family). Profiling Canadian Families III. Ottawa: VIF, 2004.

- Warner-Smith, Penny and Carla Imbruglia. 2001. ‘Motherhood, Employment and Health: Is There a Deepening Divide between Women?’ Just Policy 24 (December): 24-32.

- Whiteford, P. “Assistance for Families: An Assessment of Australian Family Policies from an International Perspective.” Keynote Address to the 10th annual conference of the Australian Institute of Family Studies. 9-11 July 2008. <www.aifs.gov.au>

- Whitehead, Margaret; Bo Burström and Finn Diderichsen. “Social Policies and the Pathways to Inequalities in Health: A Comparative Analysis of Lone mothers in Britain and Sweden.” Social Science and Medicine 50.2 (2000): 255-270. Print.

- Worth, Heather B. and Karen E. McMillan. “Ill-Prepared for the Labour Market: Health Status in a Sample of Single Mothers on Welfare.” Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 21.March (2004): 83-97.

- Wu, Zheng and Christoph Schimmele. “Divorce and Repartnering.” Families: Changing Trends in Canada 6th edition. Ed. (M. Baker). Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson. 2009. 154-178. Print.

- Zhang, Xuelin. “Earnings of women with and without children.” Perspectives March (2009): 5-13. Print.

List of tables

Table 1

Employment/Population Ratios and Unemployment Rates of Males and Females Aged 15-64 in the Liberal Welfare States, 1994 and 2007

Table 2

Percentage of Persons Aged 25-54 with and without children, 2000 Working Part-Time by Sex and Presence of Children, 2000

Table 3

The Change in the Gender Wage Gap[*] and the Incidence of Low Pay[**]

Table 4

Childcare Costs as % of Net Income for Working Couples and Lone Parents

Table 5

Employment and Poverty Rates in One-Parent Households

Table 6

Household Debt and Net Wealth as % of Annual Disposable Income, 1995 and 2005

Table 7

Social Spending on Families[*] as % of Gross Domestic Product, 2003