Abstracts

Abstract

A rock labyrinth in the Devonian Palliser Formation, which dips at 24° in the direction 224°, occurs in the Front Ranges of the Rocky Mountains, 5 km northeast of the town of Jasper, Alberta. The area that composes the Rock and Boulder Gardens, 200 m by 500 m in size, is visible on aerial photographs of the Maligne Valley. The labyrinth is distinguished by the regular arrangement of large blocks of carbonates that are separated by widely-gaping joint planes. Kinematic freedom for the translation of these blocks was created when erosion of the south slope allowed blocks to slide out of the hanging Maligne Valley into the Athabasca Valley. The rock labyrinth is believed to have formed under periglacial conditions, driven by the build up of snow in open joints exerting a downslope force on blocks.

Résumé

Dans la Formation dévonienne de Palliser se trouve un labyrinthe rocheux orienté à 224°, dont la pente est de 24° ; il est situé dans les chaînes frontales des montagnes Rocheuses, à 5 km au nord-est de la ville de Jasper, en Alberta. La zone des Rock and Boulder Gardens, qui couvre une superficie de 200 par 500 m, est discernable sur les photographies aériennes de la vallée Maligne. Le labyrinthe se distingue par l’agencement régulier de grands blocs de carbonate séparés par des diaclases béantes. En rendant possible la translation des blocs, l’érosion de la pente sud a permis leur glissement de la vallée suspendue Maligne vers la vallée Athabasca. La formation du labyrinthe rocheux, survenue à la faveur de conditions périglaciaires, aurait été déclenchée par l’accumulation de neige dans les diaclases ouvertes, laquelle aurait exercé sur les blocs une pression vers le bas de la pente.

Article body

Introduction

A rock labyrinth, known as the Rock and Boulder Gardens occurs in the Colin Range of the Rocky Mountains at a latitude of 52° 55’ 38” W and a longitude of 118° 00’ 50” N at an elevation of 1 060 m asl, 5 km northeast of Jasper, in Jasper National Park (Fig. 1). The labyrinth is similar to those described by Sokolov (1961), in which blocks separated along joints by translation along bedding surfaces. Simmons and Cruden (1980) described a similar rock labyrinth in the Front Ranges of the Rocky Mountains.

The structural geology and slope, that control the mode of movement in the labyrinth, and the possible modes of rock slope movement are discussed.

Geology

The Rock and Boulder Gardens are developed towards the top of the Palliser Formation (Fig. 1), a thickly-bedded Devonian limestone with dolomitic mottling (Mountjoy and Price, 1985). The upper section of the Palliser contains beds with indistinct, thin to medium bedding.

The dip of bedding ranges from 14° to 47°, toward 198° to 270°, with an average 24° dip. The average dip was calculated using the program Dips (Hoek and Diederichs, 1989), using weighted contouring of the data points. Two sets of joints occur perpendicular to bedding, one parallel to the strike of the beds, the other parallel to their dip.

Labyrinth

The boulders in the labyrinth are all rectangular prisms with little rounding; they appear to have broken apart along joint surfaces, and some of these have karren on them. The average bedding dip within the labyrinth is 24° toward 224°, yet the range of dip angles and dip directions (Fig. 2) indicate that some of the blocks have rotated. Dip angles range from 18° to 45° for the blocks that are not obviously rotated, and up to 65° for the blocks that do appear to have rotated. Dip directions in the labyrinth range from 198° to 270° for the blocks that do not appear to be rotated, and up to 300° for blocks that are not in their original orientation. Joint orientations for the labyrinth show two preferred orientations about the strike and dip of the bedding.

A map of the labyrinth produced by traverses along the joints shows the nature of the deposit (Fig. 2). The largest block within the labyrinth, the Big Boulder, is 11.1 m high, 12.0 m wide in the direction of dip, and 19.2 m wide in the direction of strike of the bedding within the block (Fig. 2). The separation of joints ranges up to 9.0 m with the common spacing between 1 and 2 m. Where the blocks are separated along joints, pine needles, rock and boulder debris, fallen trees, moss and other vegetation fill in the gaps (Hincks, 2003).

Scarp and Sink

The sink of the Rock and Boulder Gardens is the wedge-shaped depression visible on aerial photos. The depression is bounded to the south by a subvertical rock wall, the Rock Gardens, which trends east-west. A much gentler slope of 14° to 47° to the southwest, the scarp, bounds the feature to the north and the east. The sink is bounded to the west by a transitional area, filled with boulders in different orientations, into the labyrinth. The boundary between the sink and the labyrinth is marked by large, displaced blocks in the depression and is densely forested.

Figure 1

Bedrock geology in the vicinity of the Rock and Boulder Gardens, the scarp and sink, the labyrinth and the colluvium.

Géologie du substratum dans le secteur de Rock and Boulder Gardens, escarpement, cuvette, labyrinthe et colluvions.

Figure 2

Map of the labyrinth and some orientations of other boulders down slope, at a scale of 1:500.

Carte du labyrinthe et orientation de quelques gros blocs en bas de pente, à l’échelle de 1/500.

Other Examples of Rock Labyrinths and Rock Cities

Sokolov (1961) defined a labyrinth as “a very distinctive type of block slide, related in a general way with settling on slopes” (p. 72). The labyrinth that he described from the Caucasus involved rocks with dips between 10° and 23° on slopes of 30° to 40° into the Khosta River canyon. The labyrinth formed in limestones that were 5.5 m thick, and movement occurred in three directions (Sokolov, 1961).

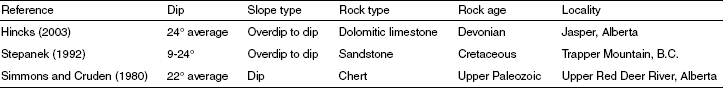

Simmons and Cruden (1980) described a rock labyrinth in Mississippian, Pennsylvanian and Permian rocks in the Front Ranges of the Rocky Mountains in Alberta, west of the Red Deer River (Table I). The average dip of the rocks in the area was 22°, with two sets of joints perpendicular to bedding, formed in chert and sandstone. Simmons and Cruden (1980) proposed that the labyrinth was formed by the dilation of joints through the formation of ice wedges.

Another labyrinth in the Canadian Rocky Mountains was described by Stepanek (1992). Stepanek stated that “it is believed that this type of movement is more widespread than previously considered.” (p. 231). The rock slide occurs in Cretaceous sandstone interbedded with shale, with dips ranging between 9° and 24°. Stepanek (1992) concluded that ice wedging under periglacial conditions and high pore-pressures were probably involved in the development of this rock slide.

While Jackson (2002) has pointed out that the labyrinth type of movement occurs where resistant rock overlies less resistant rock, our example indicates all that is necessary is the presence of very thickly bedded, resistant rock with widely-spaced perpendicular joints.

Discussion

The northeast slope of the scarp area is a dip slope and the slope of the hanging valley into the Athabasca Valley is to the west, oblique to the dip direction of bedding (Fig. 3). For a translational slide to occur on bedding, slope movement needed to occur on the south scarp first to create kinematic freedom in the dip direction (Fig. 4). Once the most southerly blocks had moved to the south and the west, toppling over the crest of the west slope, blocks behind were then kinematically free to move out from the scarp, creating the freedom for the upgradient northern blocks to slide as well. Blocks that reached the break in slope have toppled over the slope, and subsequently have been deposited as talus along the slope or within the Maligne River.

We suggest that the south wall of the feature, the Rock Gardens, was formed by the collapse of a cave system. As Kruse (1980) discussed, the Maligne cave system is fed from Medicine Lake at the current time; springs that issue from this cave system occur along the Maligne River as well as at Beauvert Lake. As the cave system collapsed, blocks to the northeast would be kinematically free to slide, allowing other blocks further upslope to move, creating the labyrinth.

Figure 3

Cross-section A-A’ as marked on Figure 1, showing the labyrinth, colluvium and alluvial sediments.

Coupe transversale A-A’ (dont l’emplacement est indiqué à la fig. 1) montrant le labyrinthe, les colluvions et les sédiments alluviaux.

Table I

Labyrinths in the Canadian Rocky Mountains

Figure 4

General trend of the slope break and resulting kinematically free blocks.

Orientation générale de la rupture de pente et des blocs libérés.

In the rock labyrinth, blocks have slid from a scarp along bedding planes, or weak layers within the stratigraphy. Cruden and Hu’s (1988) study of the frictional properties of carbonates in the Rocky Mountains found that the friction angles of carbonates range from 21° to 41°. Dolostones such as those in the Palliser had lower angles of friction and were more brittle than limestones. Many blocks inclined at 26° are not sliding at present, indicating angles of friction at least this high. Thus translational sliding at this site required assisting forces such as water pressure, snow pressure, or ice wedge growth. It is thus likely that this rock labyrinth formed under periglacial conditions following the retreat of the Maligne and Athabasca glaciers (Mountjoy, 1974; Simmons and Cruden, 1980; and Stepanek, 1992). The blocks that did not experience sufficient water, frost or snow pressure to slide the entire distance to the break in the slope formed the labyrinth proper, which thus comprises some of the last blocks to move.

Conclusions

The rock labyrinth formed by the sliding of blocks along bedding planes initially triggered by the development of a collapsed cavern feature defining the south of The Sink. Movement of the rock within the labyrinth probably occurred post-glacially, under periglacial conditions with abundant water. Based on the sizes of the blocks moved in this slide, and the distance that these blocks were moved, abundant pressures would be required to drive the movement in this slide, which would take place over an extended time period, perhaps hundreds of years. The feature is no longer active, with the exception of occasional rock fall or rock topples from the steep slope south wall.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance provided in this study by Jasper National Park, particularly the Palisades Environmental Studies Centre. The authors thank Ben Gadd, Dr. Dwayne Tannent and Dr. John Waldron for critical comments in reviewing the ideas in this paper. The authors are grateful to the journal’s reviewers for cutting this paper down to size.

References

- Cruden, D.M. and Hu, X.Q., 1988. Basic friction angles of carbonate rocks from Kanaskis Country, Canada. Bulletin of the International Association of Engineering Geology, 28: 55-59.

- Hincks, K.D., 2003. Modes of rock slope movement in the Colin Range, Jasper National Park. M.Sc. thesis, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, 232 p.

- Hoek, E. and Diederichs, M., 1989. Dips – a program for plotting, analysis and presentation of structural geology data using spherical projection techniques. Rock Engineering Group, University of Toronto, Toronto, CD-ROM.

- Jackson, L.E., Jr., 2002. Landslides and landscape evolution in the Rocky Mountains and adjacent Foothills area, p. 325-344. In S.G. Evans and J.V. DeGraff, eds., Catastrophic landslides: Effects, occurrence and mechanisms. The Geological Society of America, Boulder, Reviews in Engineering Geology 15, 411 p.

- Kruse, P.B., 1980., Karst investigations of Maligne Basin, Jasper National Park, Alberta. M.Sc. thesis, Department of Geography, University of Alberta, 114 p.

- Mountjoy, E.W., 1974. The geological story of the lower Athabasca Valley in Jasper National Park. Jasper National Park, Jasper, Contract Report 83-2.

- Mountjoy, E.W. and Price, R.A., 1985. Geology, West of Sixth Meridian, Jasper, Alberta. Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, “A” Series, Map 1611A, Scale 1:50 000.

- Simmons, J.V. and Cruden, D.M., 1980. A rock labyrinth in the Front Ranges of the Rockies, Alberta. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 17: 1300-1309.

- Sokolov, N.I., 1961. Types of displacement in hard fractured rocks on slopes p. 69-83. In I.V. Popov and F.V. Kotlov, eds., The Stability of Slopes (translation of a Russian compilation). Consultants Bureau, New York, 83 p.

- Stepanek, M., 1992. Gravitational deformations of mountain ridges in the Rocky Mountain foothills, p. 231-236. In D.H. Bell, ed., Landslides: Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Landslides (10-14 February 1992, Christchurch, New Zealand). A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

List of tables

Table I

Labyrinths in the Canadian Rocky Mountains