Abstracts

Abstract

The Nitsiyihkâson project was conceived in order to develop a resource to promote attachment and development in a manner culturally appropriate to the Indigenous (specifically Cree) people of Alberta. Promoting secure attachment between a child and his/her caregivers is crucial to ensuring positive mental health, and improving family well-being. Working collaboratively with the community of Saddle Lake, the process began by launching the project in traditional ceremony. Following this, a talking circle was held with Saddle Lake Elders to share their memories and understanding of child-rearing practices that promote attachment. Using their guidance, we produced the document “awina kiyanaw”, which focuses on Cree stories and teachings, for parents to share with their young children. This document will be shared within the community, and agencies interested in promoting a culturally-appropriate approach to parenting. We then examined the cross-cultural applicability of these practices and produced a Resource Manual for service providers, comparing traditional ways-of-knowing with current neurobiological and epigenetic scientific understanding. We believe this helps those working with Indigenous families better understand their culture, and appreciate the wisdom in its teachings. In this paper, we present those findings and their ramifications.

Keywords:

- parenting,

- attachment,

- early childhood,

- Indigenous practices

Article body

The authors would like to dedicate this publication to Community Elder George Bretton, who passed away in 2013. His kindness and wisdom were appreciated and will be remembered.

Introduction

Our goal in the Nitsiyihkâson project was to develop a resource to promote childhood attachment within Indigenous (specifically Cree) families, in ways that are culturally appropriate, using their teachings to illustrate principles of early brain development. The project stemmed from the need to develop a resource for CATCH (Collaborative Assessment and Treatment for Children’s Health), a multi-agency wraparound program for infant mental health. Because one of the two pilot sites for CATCH sees only Indigenous children - many of whom live off-reserve, some with foster families not of Indigenous descent – we saw the need to develop a parenting resource to help promote traditional practices that are also supported by neuroscientific evidence.

Translated loosely, Nitsiyihkâson means “my name is”. However, the term encompasses more than the factual statement – it relates to the kinship connections of the child to the network of social relationships in the community, and indeed the genetic and spiritual connections the child shares with their ancestors. Therefore, it seeks to understand the child’s connection, linkage, and attachment. The Nitsiyihkâson parenting resource, awina kiyanaw (“who are we”; in press), was developed to help parents understand the importance of behaviors that promote attachment with their infants and children, and the traditional teachings which support these practices.

Out of respect for the community members who helped produce this work, we are attempting to translate the teachings into western language while being respectful of Indigenous beliefs regarding birth, infancy, and early childhood development.

Methods

The methods used in this community based research (CBR) project were specific to the Indigenous culture at Saddle Lake, and the traditions of their community; we recognize that they may look different than what is commonly seen in journals. However, part of the using a CBR approach requires being respectful of the community, and understanding and incorporating their beliefs and values. The project could not have been successful without such an approach.

While conceived academically, the project was started in ceremony and shaped by the community. It began with a traditional pipe ceremony and feast, led by Elders from Saddle Lake, where the proposed methodology was blessed. It was then shaped via a half-day ethics approval process at the Blue Quills First Nations College, followed by a full day sharing circle in which stories were told relating to attachment and child rearing. These teachings were then transcribed from Cree to English. Themes and important ideas were extracted, and woven into a set of teachings arranged in developmental order. We clarify and expand upon these methodological steps below and discuss how they differ from similar western processes.

Initial Discussion with Elders

Ceremony is an essential part of Indigenous teaching, as ceremony creates connection between self and spirit. In traditional ways of knowing, you must first acknowledge the Creator, and ensure that the research being proposed is fundamentally desirable to, and seen as worthy by, the community.

We met with identified community Elders to share ideas about the project, gather their initial impressions, inviting them to share their thoughts and/or concerns. This meeting began with smudge and prayer to ask for guidance and wisdom from the Creator. We discussed the importance of addressing factors such as the role of oral history in sharing knowledge and beliefs; differing roles of males and females in child rearing; the role of residential schools in creating attachment difficulties in Indigenous families; beliefs about what children bring into the world (i.e., the spiritual component of child rearing); and maintaining a strength-based focus to the research.

Pipe Ceremony

The initial discussion helped guide us with our next steps, which included a formal pipe ceremony and feast, including the offering of tobacco and cloth. This was done through guidance and support of Elders and pipe holders from the Saddle Lake community. Within that ceremony, we also received the name for the project, Nitsiyihkâson.

It is noteworthy that this process was followed prior to obtaining ethics approval; while it is acknowledged within the research community that ethics is an important first step in any research endeavour, we wanted to ensure we practiced Indigenous research protocols, acknowledging the Creator and receiving the blessing of the Elders in the community prior to proceeding. Without their approval, the project could not have advanced.

Ethics Meeting

Our next step was to meet with the Blue Quills College research ethics committee to present the project. The team travelled to St. Paul, Alberta to meet with them. However, seeking to abide by the principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP), the ethics committee also included elders and interested students, and involved a discussion as to what was best for the community. Thus, the meeting not only explored issues of ethics, it encompassed a teaching opportunity for students and a discussion of community values.

As per protocol for sharing traditional stories and facilitating a sharing circle, conversation was focused on where and when these stories should be shared. The conversation further evolved with the appropriateness of recording and taping the stories. In this way, the ethics discussion necessarily differed from those often held in western universities, as it required a greater level of openness and flexibility from the team, and served the additional purpose of helping solve logistical issues while addressing concerns regarding community involvement.

Access to Elders

Team members of the research committee that resided in the Saddle Lake First Nation approached the Elders with traditional protocol of tobacco and cloth, and invited them to participate in the Sharing Circle.

Sharing Circle

Community Elders and the research team came together as a group on the Blue Quills College campus, and the day began with prayer and a smudge ceremony. The Sharing Circle involved a full-day of meeting, in which questions were posed to the Elders, and a talking stick (in our case, a microphone used to record the conversation) was passed around the circle clockwise. The group process involved a team member (X.X.) facilitating, providing context and encouraging discussion on the questions. Once each individual had a chance to address a question, the stick was passed around once more to ensure that individuals were able to express any ideas that occurred to them in listening to the others speak. Elders received lunch and small honorarium for their participation.

Importantly, Elders were encouraged to discuss questions in Cree, in an effort to maximize comfort an capture the true sentiments shared amongst the community members. While this somewhat complicated the process (transcription of the full day of conversation had to be done afterward), it was clearly important to the process – in fact, when one question was discussed (regarding residential schools), the tone of the conversation changed markedly and most individuals started speaking English. In discussions afterward, it was posited that this shift reflected their discomfort in reliving the events surrounding colonization.

Thanks Giving and Project Completion

As a final step of the process, another gathering occurred in the community at Blue Quills College. This again was to offer thanks to the Creator, the community, and the Elders that participated and supported the project. At this meeting, preliminary results were discussed, as were ideas about how best to share the information.

Results

Section 1: Prebirth

Maternal-attachment with the unborn child. Cree teachings highlight the need for the mother, and the rest of the family, to connect with the unborn child – this can be through song, such as traditional music, or via storytelling. Modern neuroscience supports the idea that the child is developing sensory capacities pre-birth. For instance, tastebuds first appear 8-12 weeks after conception, and early taste perception can influence taste decisions after birth. Sensitivity to light appears around 16 weeks, with vision continuing to develop after birth. The sense of touch develops between 8-20 weeks, and sense of smell develops around week 28 (Enfamil, 2012; pregnancy.org, n.d.). Infants have been shown to orient to the sound of their parents’ voice at as little as 16 weeks of age (What to Expect, n.d.).

Science confirms the nature of the prenatal attachment relationship (between the infant’s development in the womb, and the woman’s development in becoming a mother) is critical. There has been increased recognition over the past 20 years that the relationship between a mother and child starts before a child is born; in fact, research demonstrates a correlation between prenatal attachment and postnatal attachment (Alhusen, 2008). Furthermore, optimal attachment in early infancy has been identified as an integral component in the future development of a child (Oppenheim, Koren-Karie, and Sagi-Schwartz, 2007).

Prenatal health and nutrition. Some evidence suggests that positive health behaviours (e.g., visiting a doctor regularly for prenatal care; maintaining a healthy diet and exercise routine) are associated with improved maternal bonding while the child is still in the womb (Virtual Medical Centre, 2013). Substance abuse during pregnancy is associated with poor maternal and infant outcomes, as it may make it more difficult for the woman to do the tasks that are important for bonding with her infant.

However, beyond the necessity of maintaining good health during the pregnancy, Indigenous teachings tell us that the issue is broader – it is about the idea of realizing that actions have consequences, not only for the individual but for the generations that follow. In Cree teachings for example, it is said that an event will carry repercussions for 7 generations. It is worthwhile to consider the multi-generational cycles of FASD, spousal abuse, and alcoholism in this context. Interestingly, the idea that events which cause stress to the parent (whether psychological or physical) directly translate to the child has been borne out by recent evidence. Epigenetics suggests that poor parenting or neglect actually result in changes of the genetic structure of the child. This is because the way in which gene transcription and protein manufacture occurs is actually altered by early stressors (Scott, 2012).

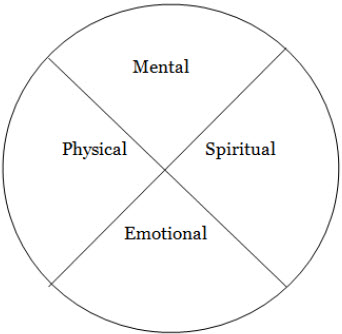

Further, their teachings suggest that negative issues are caused by an imbalance in mind, body and spirit (Elders use the word pāstāhowin to describe this imbalance); this is one of the lessons behind the Cree circle of life – that there needs to be equilibrium between the mental, emotional, physical and spiritual aspects of the self (see Figure 1, left). The expectant mother in particular needs to try to maintain this balance. Similarly, a role of the parents and family is to assist the newborn in finding this equilibrium, particularly in helping them find a sense of calm alertness, when they are either understimulated or upset. Intriguingly, this is also one of observations of the neurorelational framework (Lillas & Turnbull, 2009).

Figure 1

Cree Teaching Circle

However, despite the potential for stressors to create imbalance, science also shows that potential damage can, to some extent, be reversed (Perry & Pollard, 1998). It is only in the last couple decades that modern science has accepted the concept of neural plasticity, the idea that brains are changeable and can be altered following long term damage, such as that resulting from abuse or neglect. In fact, Indigenous teachings suggest that it is through traditional practices and ceremony balance can be restored.

That said, science also shows that trying to change behavior or build skills in circuitry that was miswired in the first place takes more work and is less effective. The most effective way to produce resilient behavior is to nurture and protect the developing brain as it evolves (Early Brain & Biological Development, 2010).

Section message. Professionals working with at-risk families likely bring with them their own belief system that may support or conflict with the Indigenous teachings described above. That said, science supports paying attention to the pregnancy, being thoughtful and attempting to be healthy, and making those first initial efforts to bond with the child (e.g., via singing, story-telling, etc.) prebirth. In fact, it may be that if prospective parents are not engaged in the process, they will miss opportunities (or critical periods) for these initial bonding experiences. Nor will they pay attention to healthy habits regarding nutrition and drug use, essential to a healthy baby. Science is only now exploring concepts such as epigenetics and plasticity, but Indigenous teachings have suggested these scientific facts for centuries.

Section 2: Birth

Responsivity. Indigenous teachings place great importance on meeting the newborn child’s needs. Their belief is, the infant “always cries for a reason”; in other words, when a child cries it is because they need something and the parent should tend to them. Rather than following the western custom of feeding a newborn every two hours around the clock, the Cree believe that the child communicates its needs through its cries. Thus, they place great importance on being atuned to the infant, and maintaining a reciprocal relationship with him or her. This reciprocity is now seen as essential to the healthy development of the newborn, a type of “serve and return” back-and-forth communication between the parent and child.

Early sensory experiences. The Elders described early sensory experiences, such as “singing the baby into the world” with a special song (nikamowin); as well as early experiences conveyed through smell and touch. These processes lay the fundamental groundwork for how the child experiences the world. In western culture, parents are often left on their own to determine what kind of environment is “best” for their newborn, but new parents may be confused or challenged, and require guidance. The Cree teachings place importance on those early days in connecting to the infant in a physical way.

During the earliest stages of development, the baby’s brain is growing and changing extremely rapidly. One of the important activities occurring during early development is synaptic pruning, in which unused brain connections are eliminated. This process begins at birth and extends until adolescence (Iglesias, Eriksson, Grize, Tomassini, and Villa, 2005). Importantly, a major determinant of which connections remain and which are eliminated is use – a principle jokingly referred to as “use it or lose it”. This means, however, that the important sensory experiences the child undergoes early on help to determine which pathways will remain and be strengthened, and which will be eliminated. Thus, developing and maintaining these early physical connections with the child is key.

Swing. The swing carries with it many teachings for caring for the newborn. Use of the swing continues to assist the infant with maintaining their spiritual connection. It soothes them and reminds them of the comfort and safety of the womb. However, while being placed in a swing is seen as an important sensory experience, the elders caution against keeping the child in the swing overnight or unattended. According to Cree teachings, this is to ensure that the child remains “grounded” (Gladue, 2002). Thus, the swing is one of the important sensory experiences early on.

Mossbag. As mentioned above, the Elders placed a lot of importance on holding the child, and actual skin-to-skin contact. The belief is that children who are carried in a mossbag tend to have calmer spirits. While western culture understands the importance of restraint systems (e.g., booster seats, car seats, carriers, etc.), the Elders brought attention to the important issue to bonding with the child simply through holding and carrying it. For instance, there are discrete words in Cree that express the concepts of “nurturing and showing affection” to a baby (ocemōhkatikawiyan) and “the songs sung while playing with the child” (nïmihawasowin). Notably, comparable terms do not exist in English. Scientific research supports the lasting effects of early skin-to-skin contact on an infant’s self-regulation, social relatedness and capacity to handle stress and frustration (Feldman, 2011). This author hypothesized that the continuous physical contact soothes the infant and emphasizes the underlying connectedness between members of the cultural group, while in more individualistic societies mothers prefer more active forms of touch. Using hundreds of participants, Anderson, Moore, Hepworth, and Bergman (2004) were able to demonstrate positive effects of early skin-to-skin contact on measures of breastfeeding, maternal touch, and other maternal attachment behaviors.

However, according to the teachings, the mossbag is not simply a carrying device for the child. The broader idea is that the very construction of the bag is meant to mimic the mother’s womb – thus aiding the child’s transition into the world. For instance, the lacing on the bag can be likened to the mother’s ribcage. Essentially, this means that the parent can decide and control how much exposure is appropriate for the child from moment to moment, helping the child build their capacity for self-regulation. The mossbag assists the process of atunement between the parent and child, as to whether the child is ready for exposure to the world or requires the safety of parental contact.

Sleeping. Although for awhile it was seen as dangerous or inappropriate, modern science is beginning to recognize the acceptability of co-sleeping (i.e., sleeping in bed with an infant; Neuroanthropology, 2008). In fact, some research suggests lower rates of SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome) among infants who co-sleep with their parents. Co-sleeping also results in healthier infants, in that that bedsharing increases rates of breastfeeding while increasing sleep for both mother and baby, potentially reducing infant illness. Thus, according to the authors,

irrepressible (ancient) neurologically-based infant responses to maternal smells, movements and touch altogether reduce infant crying while positively regulating infant breathing, body temperature, absorption of calories, stress hormone levels, immune status, and oxygenation. In short, and as mentioned above, cosleeping (whether on the same surface or not) facilitates positive clinical changes including more infant sleep and seems to make, well, babies happy.

Neuroanthropology, 2008

As it stands, the authors state that the evidence for co-sleeping remains mixed, with most studies supporting it except for the case of couch co-sleeping, which can result in suffocation. Parents should also be advised not to bedshare if inebriated or otherwise desensitized. Similarly, the relationship of the parents should also be a factor worthy of consideration.

Breastfeeding. Science supports the importance of breastfeeding, both in developing a healthy immune system, as well as in giving opportunity for the mother and child to bond (the Baby Bond, n.d.). Breast milk is a complete, easy-to-digest form of nutrition that contains antibodies, protecting the child from illness. Breastfed babies are better able to fight off infection, and require fewer visits to the doctor. This also gives mother and child an opportunity to connect, often through eye contact, but also through smell and taste, engaging all the child’s senses, and bonding mother with child through a multi-sensory process.

Belly button ceremony. The Cree have a practice of making a special ritual of disposing of the newborn’s belly button. Rather than throwing it away, they will make a special effort to, for example, bury it in a special place. The belief is that where the belly button is placed helps to define the path the child will take in the world. Burying it helps to keep the child grounded, so that his or her spirit has a home.

Whether or not one might view this as superstitious, it reflects the Indigenous view that it is important to give thought to the child’s place and path in the world; that the wishes placed upon the child’s future are valuable and require conscious attention.

Naming ceremony. There are names given through ceremony that become a child’s spirit name. These names help them connect to their spirit and the spirit world. They have great meaning, and often follow the child throughout his or her lifetime.

However, it is also common for Cree families to grant the child a nickname, informally. This process represents an opportunity for family members to bond with the new baby. This may be via seemingly superficial traits (e.g., “she looks like cousin Shelley; that is how we should refer to her”; “the baby’s cry is like the squeak of a mouse!”) – but no matter how it is determined, this nickname serves the purpose of outlining a special connection between the child and members of the family. Often, these names are of a teasing, affectionate nature, and kept personal amongst family or community members.

Section message. Indigenous teachings around birth and early infancy focus on the importance of developing bonds with and being responsive to the infant, in both physical (e.g., co-sleeping, breastfeeding, using the moss-bag) and more spiritual ways (e.g., the belly button and naming Ceremonies). In fact, both are fundamental to the development of positive attachment relationships. All these practices will be reflected in the growth and development of the child, helping them move to the next stage of development.

Section 3: Early childhood development

Importance of play and being out in nature. Scientific evidence supports that independent exploration of nature is vital to learning a number of skills and abilities (Janssen & LeBlanc, 2010; p. 40). For instance, research from the Arbor Day Foundation (2013) suggests that outdoor play is fundamental to:

Better social and physical development

Improved fitness and motor skills

Stronger powers of observation, creativity, and imaginative play

Improved collaboration, with decreased bullying

Reduced stress

Feelings of empathy for nature, encouraging environmental stewardship

Broad-based development and learning across the curriculum

Just as importantly, the more time spent in physical activity outdoors, the less time spent in sedentary pursuits (i.e., technology; Flett, Moore, Pfeiffer, Belonga, and Navarre, 2010). The physical benefits of being outdoors include lower blood pressure, heart rate and muscle tension. There is also a relationship between the amount of time spent outdoors and child’s overall level of physical activity, thereby battling childhood obesity (Munoz, S-A., 2009; p. 9) and type II diabetes. Just as importantly, time spent outdoors is also related to stress reduction and reduced mental fatigue, potentially reducing the odds of mental illness such as depression, anxiety and ADHD (McCurdy, Winterbottom, Mehta, and Roberts, 2010).

However, the teachings go beyond the positive health benefits of play. The exploration of nature is also seen as important to learning survival skills (e.g., which berries are edible; what parts of a slope are most stable), as well as building respect and love for the environment.

Natural consequences and learning to stand up for oneself. The Elders describe the importance of letting the child experience the natural consequences of bad behavior. They believe it is vitally important for the child to learn difficult lessons themselves, rather than vicariously.

This idea links strongly to neuroscientific principles of memory development; individual experience with and learning of a contingency is more powerful than having that event explained to you, or witnessing someone else go through the event. In fact, procedural memory is by far the strongest type of memory formed (i.e., as compared to declarative, or fact-based, memory), being resistant to experiences such as amnesia (Cavaco, Anderson, Allen, Castro-Caldas, and Damasio, 2004). Interestingly, research has shown that trauma (e.g., post traumatic stress disorder) has the result of shrinking brain structures responsible for forming memories (the hippocampus; Herrmann et al., 2012). One might ask whether building procedural memory – which is less prone to cell loss in those regions (Kolb & Whishaw, 1990; p. 555) – could have a protective effect on children who experience trauma. So, while it is always important to keep children safe, it is just as important to let them experience the negative things that may happen when they are out exploring the world - within limits. This is how the child develops confidence and self-respect.

The Elders also spoke strongly about “not taking the part of the child”; in other words, letting children fight their own battles. The child should be encouraged to find his or her own voice, and to speak up for themselves. This process, known as individuation, is now known to be crucial to child development. In some ways, this belief system stands in stark contrast to many modern practices, in which parents generally, for example, will approach a teacher if they feel their child has been treated unfairly. While modern thinking appears to be that the child needs an “advocate”, this issue is really related to the idea of teaching natural consequences; Indigenous teachings place value on learning through direct experience.

The willow teachings. The Cree have a series of teachings referring to the willow stick the child is told to go and find, which represents the object of their discipline. While modern science does not support the use of corporal punishment, it is important to understand that what the child is learning here is that there are consequences for negative behavior, and more importantly, that he or she will be part of the discussion in determining the severity of those consequences. In this way, the willow teachings actually empower the child.

Importance of playing together and building relationships. The Elders put an emphasis on developing good, peaceful peer relationships. One elder describes it as being taught, “to be able to play and interact with our peers, other children and not to horde our toys but to share it with them.” This seems like a simple lesson, but nowadays there is a much stronger emphasis on achievement and being first in the class; competition rather than cooperation. There is an importance placed on socialization:

Today our children are being raised by themselves, they don’t know each other, they don’t understand each other because there are no gathering places for them, even places where they can socialize and talk to each other. The only thing they do is text.

Science has recognized the protective effects of interconnection since Emile Durkheim published his landmark study of suicide in 1897, finding lower rates of suicide among cultures with stronger integration (Suicide [book], n.d.). Modern theories of brain development also place importance on socialization and relationship; children raised in isolation show deficits in areas such as mental health, well-being, and perceived social support (Canetti, Bachar, Galili-Weisstub, De-Nour, and Shalev, 1997). Similarly, youngsters who report social exclusion are 2-3 times more likely to experience depressive symptoms than their socially-connected peers (Glover, Burns, Butler, and Patton, 1998). Moreover, children of a lower socio-economic status are more likely to report social exclusion (Davies, Davis, Cook, and Waters, 2008). It is also noteworthy that some relationship practices differ in Indigenous communities compared to the western view. For instance, teasing is a common method of bonding amongst community members. It is not done maliciously, rather acknowledging that the individual is part of the group; that he or she belongs - that the child is well known, understood, and most importantly accepted among community members. So, while teasing is a common method of exclusion in western cultures, it carries a different meaning for the Cree.

Moreover, the types of relationships valued by Indigenous communities are much broader than those traditionally considered as part of the western definition of “family”. Beyond the parent-child relationship, they encompass extended family, and even the broader community. This is important, because one role of the parents it to help teach the children gender-appropriate behaviors and practices, roles and responsibilities.

However, the Elders also pointed out that the entire Indigenous concept of relationship is different, with the idea being that “you are the relationship”, as your connections with others both reflect who you are and shape who you are. In other words, there is a focus on interconnectedness. This relates to the Cree concept of Wahkohtowin, the idea that “we are all related”. In fact, distant relatives are treated like first degree relatives, with cousins treated as siblings, and great aunts/uncles not referred to as such. Relationships among kin are, in some ways, closer and more personal than those experienced in the western culture. In many ways, this point of view reflects the idea that it takes a village to raise a child.

Section message. Indigenous teachings around early development and child rearing focus on teaching the child independence, respect, responsibility, and relationship. The teachings show the value of exploring the world, learning through experience, but also respecting boundaries and showing kindness and charity to others. In so doing, they recognize that cognitive, emotional, and social capacities are interconnected, which is fundamental to brain development as the brain uses some of these functions to enrich others. A main goal behind these teachings to help the child learn roles, expectations, and responsibilities, ultimately preparing them for adulthood, teaching skills to allow children to take their place in the community.

Discussion

This publication documents the scientific merit underlying the practices described in the Nitsiyihkâson parenting resource. The parallels between Cree teachings and current scientific thought are striking. There are many dichotomies between western and Indigenous world views. Paradoxically, “new” brain research is now espousing the same parenting practices as Indigenous teachings have been promoting for centuries. It is the conclusion of our study team that, in some ways, science is catching up with traditional practices that have been passed down from generation to generation for hundreds of years. That is, the perspectives of the Indigenous community, their traditional practices and techniques, are now being borne out by modern neuroscience. It is noteworthy that these teachings were practiced pre-contact, and were passed down through oral tradition, ceremony, and relational concepts, but we in the western world are only now starting to appreciate their true value. For this reason, Indigenous thought is both relevant and prescient in terms of our understanding of attachment and bonding.

In one sense, the fact that the scientific community might be surprised to hear this underscores the issue with colonization: until western science has “proven” a phenomenon to be true, it means little and is taken as curious or hypothetical. In fact, this point of view perpetuates colonialistic attitudes towards Indigenous populations. Moreover, this document suggests that, ironically, our efforts to restrict or destroy these practices in the 20th century actually set back child rearing and the promotion of adult-child attachment in Indigenous communities.

As has been elaborated previously, “it is impossible to understand First Nation community health without considering the cultural foundation upon which the community is built” (Keith, 2011). It is our hope that awina kiyanaw and the accompanying Resource Manual provide to readers a better understanding of Indigenous practices promoting attachment, and help build a platform to better relate with Indigenous children and families.

Appendices

Bibliography

- Alhusen, J.L. (2008). A literature update on maternal-fetal attachment. Journal of Obstetrical and Gynecological Neonatal Nursing,37(3): 315–328.

- Anderson, G.C., Moore, E., Hepworth, J., and Bergman, N. (2004). Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2004. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Arbor Day Foundation. (2013, August 2). Research shows regular time in nature… Retrieved from: http://www.natureexplore.org/research/documents/NatureExplore_KeySkills.pdf

- Baby Bond. (n.d.). Nursing: It’s more than breastfeeding and every mother can do it. Retrieved from: http://thebabybond.com/ComfortNursing.html

- Canetti, L., Bachar, E., Galili-Weisstub, E., De-Nour, A.K., and Shalev, A.Y. (1997). Parental bonding and mental health in adolescence. Adolescence, 32(126): 381-94.

- Cavaco, S., Anderson, S.W., Allen, J.S., Castro-Caldas, A., and Damasio, H. (2004). The scope of preserved procedural memory in amnesia. Brain, 127 (Pt 8), 1853-67.

- Davies, B., Davis, E., Cook, K. and Waters, E. (2008). Getting the complete picture: combining parental and child data to identify the barriers to social inclusion for children living in low socio-economic areas. Child: Care, Health & Development, 34(2): 214-22.

- Early Brain & Biological Development: A Science in Society Symposium. Summary Report. (2010). Calgary, AB, Canada: The Norlien Foundation.

- Enfamil (2012, May 1). Sensory development [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.enfamil.com/app/iwp/enf10/content.do?dm=enf&id=/Consumer_Home3/Prenatal3/Prenatal_Articles/developingSenses&iwpst=B2C&ls=0&csred=1&r=3521908093

- Feldman, R. (2011). Maternal Touch and the Developing Infant in M.J. Hertenstein & S. J. Weiss (Eds), The Handbook of Touch: Neuroscience, Behavioral and Health Perspectives (p. 373 -407). New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Flett, R.M., Moore, R.W., Pfeiffer, K.A., Belonga, J. & Navarre, J. (2010). Connecting Children and Family with Nature-Based Physical Activity. American Journal of Health Education, 41 (5): 292-300.

- Gladue, Y.I. (2002).Traditional swing provides therapy for the inner child. Alberta Sweetgrass, 9 (11): 17. Retrieved from: http://www.ammsa.com/node/25712

- Glover, S., Burns, J., Butler, H. & Patton, G. (1998). Social environs and the emotional well-being of young people. Family Matters, 49: 11–16.

- Herrmann, L. Ionescu, I.A., Henes, K., Golub, Y., Wang, N., Xin, R., Buell, D.R., Holsboer, F., Wotjak, C.T. and Schmidt, U. (2012). Long-lasting hippocampal synaptic protein loss in a mouse model of posttraumatic stress disorder. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 7(8):e42603.

- Iglesias, J., Eriksson, J., Grize, F., Tomassini, M., and Villa, A. (2005). Dynamics of pruning in simulated large-scale spiking neural networks. BioSystems 79 (9): 11-20.

- Janssen I. and LeBlanc A. (2010). Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity. Vol. 7: p 40.

- Keith, L. (2011). First Nation community health – linking culture and quality care. Qmentum Quarterly, Quality in Health Care, 3(2): 10–13.

- Kolb, B. and Whishaw, I.Q. (1990). Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 3rd Ed. McCurdy, L.E., Winterbottom, K.E., Mehta, S.S., & Roberts, J.R. (2010). Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children’s health. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 40: 102-117.

- Lillas, C. and Turnbull, J. (2009). Infant/Child Mental Health, Early Intervention, and Relationship-Based Therapies: A Neurorelational Framework for Interdisciplinary Practice. New York: W. W. Norton. Part of the Interpersonal Neurobiology Series wherein Dan Siegel, MD original Series Editor; Allan Schore, PhD, current Series Editor.

- Munoz, S-A. (2009). Children in the Outdoors: A Literature Review. In: Sustainable Development Research. Scotland: Horizon.

- Neuroanthropology. (2008, December 21). Co-sleeping and biological imperatives: Why human babies do not and should not sleep alone. Retrieved from: http://neuroanthropology.net/2008/12/21/cosleeping-and-biological-imperatives-why-human-babies-do-not-and-should-not-sleep-alone/

- Oppenheim, D., Koren-Karie, N., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2007). Emotion dialogues between mothers and children at 4.5 and 7.5 years: Relations with children's attachment at 1 year. Child Development, 78(1): 38-52.

- Perry, B. D. and Pollard, R. (1998). Homeostasis, stress, trauma, and adaptation: A neurodevelopmental view of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 7[1], 33-51.

- Pregnancy.org. (n.d.). Fetal development. Retrieved from: http://www.pregnancy.org/fetaldevelopment

- Scott, S. (2012). Parenting quality and children’s mental health: Biological mechanisms and psychological interventions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25: 301-306.

- Suicide (book). (n.d.) Retrieved from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicide_(book) Virtual Medical Centre (2013, August 27). Bonding with your baby during pregnancy. Retrieved from: http://www.virtualmedicalcentre.com/healthandlifestyle/bonding-with-your-baby-during-pregnancy/232

- What to Expect. (n.d.). Week 16 of pregnancy: Baby's hearing develops. Retrieved from: http://www.whattoexpect.com/pregnancy/your-baby/week-16/ear.aspx

List of figures

Figure 1

Cree Teaching Circle