Abstracts

Abstract

This article was generated from the research project “Brightening Our Home Fires” (BOHF), a Photovoice project on woman’s health and wellness that took place in the Northwest Territories (NT) from 2010-2012. This research was funded by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) of Canada. Approximately 30 women from four different communities in the NT participated in this project; Behchokö, Ulukhaktok, Yellowknife and Lutsel 'ke. The method utilized in this study was Photovoice, a Participatory Action Research (PAR) model that is identified as a qualitative research approach. While the research project was a Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) prevention project, the broader focus was on issues related to health and healing within a northern context in the NT from the perspective of northern women, and within the construct of health. The primary focus of this article is the presentation of a model that was generated from a review of the research literature gaining a deeper understanding of broader social concerns in the NT. Three key factors are highlighted as critical in developing a deeper understanding of the context of women’s health issues that are important to consider in FASD prevention work: 1) trauma, 2) alcohol abuse and 3) child welfare involvement and the impact on communities in the northern territories of Canada as it presently exists in the NT. This research served to provide a broad perspective of social problems that may be mitigating factors in the presentation of FASD in a northern context.

Keywords:

- Northern Canada,

- alcohol,

- trauma,

- child,

- welfare,

- FASD,

- Aboriginal,

- Photovoice,

- social determinants of health

Article body

Introduction

The focus of this paper is to review relevant literature that supports a deeper understanding of the health and social health context in northern Canada. Since July 2009, a team of researchers and service providers working in the NT have been collaborating to develop a research project in the NT that explores the issue of trauma in the North, its relationship to alcohol use and the prevention of FASD. The Canada FASD Research Network (formerly known as the Canada Northwest Research Network) has, within its structure, a series of Network Action Teams (NATs). Individually and collectively, members of the NATs have access to a wide knowledge base in community work and research that provided a strong foundation to support the BOHF project (Badry, 2012). Membership of the research team included representatives originally from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. Membership has now expanded across the country of Canada. Monthly meetings are held to review research, discuss projects and develop knowledge and information on FASD as it relates to women’s health concerns within the broader context of their lives. The NAT focused on Women’s Social Determinants of Health as it relates to FASD and women’s health concerns linked researchers and service delivery members with concerns specific to the North West Territories. The BOHF project was developed with an understanding that prevention is best achieved through informed research that translates gathered knowledge into meaningful and practical forms that can be shared with, utilized and implemented by, local communities. While FASD prevention is a concern, the focus of this paper is on the broader context of critical factors in the NT that form a background for this work, including identification of health and social issues that are key considerations in any prevention work. Literature reviewed included academic journals in social work, health and the north, as well as government reports, and articles of interest by FASD networks.

Context for FASD prevention work

The issue of FASD prevention must be addressed in Aboriginal and Inuit communities from a cultural, historical, political and social context, that respects the past, considers the present, and holistically addresses concerns with these influences in mind. As the BOHF research focused on a highly sensitive and potentially stigmatizing issue such as maternal substance use and FASD, the approach to this project had to be constructed and embedded within communities through local contacts, discussions, conference calls or meetings whenever possible. Given the broad distances between communities in the NT, forms of communication amongst the team and the communities was often done via e-mail, Skype and phone conversations. Visits to each community took place throughout the project and team members travelled to communities to engage in the primary Photovoice work.

While the need for culturally-responsive and culturally-safe models of FASD prevention that directly addresses relationships between trauma, substance use, and FASD among Aboriginal peoples has long been identified, there remains a lack of resources to develop and implement such interventions at the community level. There is also a lack of resources to support linked, community-based research in the North evaluating intervention effectiveness (Salmon & Clarren, 2011.) While some resources exist in the NT for women struggling with health and social issues, the great distances between communities can be a barrier to readily accessing supports. Service for women in need of help and struggling with addictions, trauma and domestic violence is more readily available in larger centers such as Yellowknife, NT, than in smaller, remote communities. The Centre for Northern Families (CNF) is one example of a resource center for women that provide shelter, access to health and other supports as required. These efforts are thus in a neophyte stage in Canada, and developing a Northern agenda is critical to supporting families in the North who often do not have access to resources locally. Highlighting these issues through research is important to developing supportive interventions, resources, programs, and policies that respond to the needs of communities.

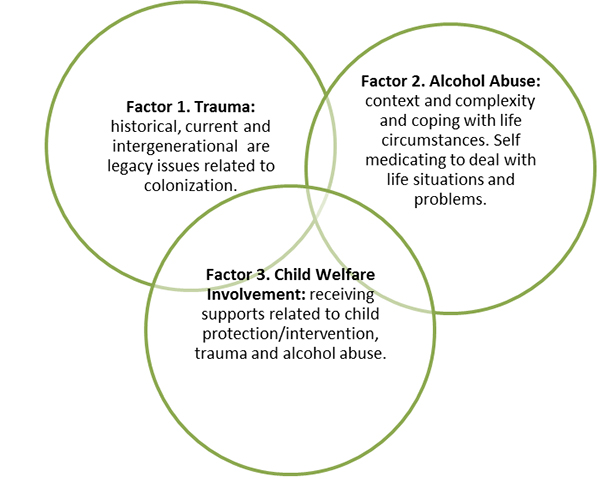

In 2011 the National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, report author, Dr. Emilie Cameron, published State of the Knowledge: Inuit Public Health specifically suggesting there is a gap on comprehensive health data on FASD and associated disabilities. The Inuit Five-Year Plan for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: 2010-2015 was published by Pauktuutit – Inuit Women of Canada and indicates that, although learning disabilities are identified, there is no comprehensive source of information that identifies children with FASD. There is growing awareness of the need to address these concerns, but a consistent infrastructure does not exist to supports children and families with these problems. This issue falls under the broader rubric of mental health and addictions and concerted efforts are being made to address these issues within Inuit communities in Canada. Alcohol is implicated in most episodes of violence, and a large percentage of injuries in the North (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), 2007). In addition, the main reason for most mental health hospitalizations for both women (48%) and men (65%) were substance related disorders. The heaviest drinking is amongst young people 15-24 closely followed by those aged 24-39. This includes the abuse of alcohol or withdrawal from alcohol (Northwest Territories, 2010, 201.) Badry (2012) wrote the Brightening Our Home Fires in the Northwest Territories Final Report. In evaluating the literature on key areas such as trauma, child welfare involvement and alcohol abuse for this report to the First Nations Inuit Health Branch, that themes emerged regarding the social concerns identified in Model 1.

Model 1

Brightening Our Home Fires: Model of Factors Related to Understanding Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in a Northern Context:

Trauma, Alcohol Abuse and Child Welfare Involvement (Wight Felske & Badry, 2012)

Factor 1: The trauma response to, and legacy of, residential schooling

Factor 2: The statistics on alcohol abuse and consumption

Factor 3: The statistics on child welfare involvement, and children receiving care from the government because of family problems and issues related to this intervention.

These indicators can be used to form social policy regarding FASD that informs approaching FASD from a cultural lens that is respectful of history while moving a health agenda forward. It targets FASD as a preventable problem while attaching intensive supports to at risk families with a goal of child and family health. This harm reduction model identifies a triad of factors that underlies the problem of FASD.

The three key areas identified above will be reviewed in greater detail in relation to existing literature and highlight in greater details the issues associated with each factor, trauma, alcohol abuse and child welfare involvement.

Factor 1: The trauma response to and legacy of residential schooling: Historical, current and intergenerational legacy issues related to colonization

When considering the diagnosis of a child, youth or adult with FASD, it is crucial to recognize that women who use alcohol during pregnancy are not doing so to harm their child. The broader issue of substance abuse is a symptom, and legacy, of multifactorial causes. The roots of trauma in Aboriginal, Metis and Inuit communities can be found in the legacy of the colonization of Canada. In Northern Canada, disruption of the family systems and structure, the marginalization from resources, including cultural resources, and the imposition of federal and provincial policies and laws worked together to create challenging conditions for families. Caron (2005), a physician, wrote about the disproportionate risk of injury and illness related to trauma in the North. Mortality rates are twice that of Canadian population, with one third of deaths caused by trauma. She advocates the importance of documenting morbidity and mortality caused by trauma in Aboriginal communities and to study the contributing factors and root causes in greater detail, beyond surface representations (Caron, 2005). Finding solutions to develop better emergency treatment through studies with Aboriginal and Inuit people and the need for better services is essential but often inhibited by the rural and remote nature of some communities. Sometimes, the cumulative impacts of multi-abuse trauma resulted in the disintegration of families, communities, and systems of wellness. Along with the disintegration of wellbeing, the use of alcohol to self-medicate arises and the emergence of FASD becomes a concern.

Unresolved issues related to past traumas and historical abuses are problematic, as they can lead to self -medicating through alcohol use as a coping mechanism. Chansonnueve (2005) identifies signs of unresolved trauma as flashbacks, nightmares, intrusive thoughts and engaging in repetitive patterns of behavior. In children such trauma can be seen in behavior that appears disorganized, chaotic and feeling agitated (p. 53). Individuals and families who do not come to terms with their traumatic experiences are likely to pass on the unresolved trauma to their children. Childhood trauma can be hidden or stored in brain circuits, and later activated by adult trauma, particularly trauma in intimate relationships. Studies on trauma and the connection to parenting have shown a linkage between childhood trauma and progressive substance abuse (Connell et. al., 2007; Wesley-Esquimaux, and Smolewski, 2004).

Intergenerational trauma is commonly used to describe trauma experienced by Aboriginal families. It is most often associated with residential school experience. It may also be the result of such actions as forced relocation, apprehension by social services, and hospitalization. Intergenerational trauma is described by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation report: “When trauma is ignored and there is no support for dealing with it, the trauma will be passed from one generation to the next. What we learn to see as “normal” when we are children, we pass on to our own children” (Aboriginal Healing Foundation 1999, A5).

Multi-abuse trauma involves active forms of abuse (e.g. sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse or neglect, emotional/psychological abuse) and coping forms of abuse (e.g. substance abuse, compulsive eating, self-harming behaviors) (Edmunds & Bland, 2011). Researchers examining stress in Aboriginal people with diabetes found stress to be multifaceted and intertwined. Intertwined stress includes: health related stress; economic stress; trauma and violence; as well as historical cultural political stress linked to identity (Bartlett, Madariaga-Vignudo, O’Neil, and Kuhnlein (2007).

The same study also found that the people drew upon cultural teachings and practices to deal with their stress. The most profound trauma affecting Aboriginal communities across Canada can be traced to the residential school experience. Trauma is a complex condition that is dependent upon a number of factors, such as age, timing of abuse, relationship with the abuser and type of abuse. Residential schools perpetuated multi-abuse trauma upon Aboriginal children. Children were taken from their families for months and sometimes years, where they were stripped of their connections to family and culture. The children suffered many abuses, and their families were powerless to protect them. Survivors and their descendants continue to live with the historical and intergenerational trauma (Chansonnueve, 2007). Trauma experience produces feelings of anomie (normlessness), powerlessness, vulnerability, frustration and confusion. This destabilizes a person’s sense of self and affects identity. The magnitude of pain, rage, and the grief of unresolved trauma continue to haunt families and communities into present times, and it is a naive notion that people simply get over trauma (Chansonneuve, 2007).

Today there are addiction treatment programs that focus on the links of trauma and addictions as an approach to treating substance abuse. Learning about the historical roots to trauma can help to find workable solutions by, and for, community members. Understanding constructs such as dislocation and colonization are critical in treatment. Dislocation means “being removed from one’s language, culture, family and community” (LaRoque 2001, 1). Dislocation is a situation that has affected Aboriginal children sent to residential schools, as well as immigrants and refugees to Canada. The construct of colonization refers to “that process of encroachment and subsequent subjugation of Aboriginal peoples since the arrival of Europeans. From the Aboriginal perspective, it refers to the loss of lands, resources, and self-direction and to the severe disturbance of cultural ways and values”(LaRoque, 2001 p.1). Today there is a greater understanding of the dynamics of violence and trauma and the connection to coping abuse, such as substance abuse (Edmund & Bland, 2011; Chansonneuve, 2005). There is also a better appreciation of the strengths within Aboriginal communities and traditional knowledge and practice (Fallot & Harris, 2009).

Factor 2: Alcohol abuse. The statistics on alcohol abuse and consumption are important to consider in terms of context, complexity and coping with life circumstances through self-medicating

Alcohol abuse is a challenging problem in the North, with heavy drinking occurring primarily in younger segments of the population. The primary source of information on alcohol use is from the Northwest Territories (2010) Health Status Report which describes heaving drinking as occurring at least once per month among people 15 years of age and older. Participants are grouped by gender, age, and rural / urban location. The percentage of youth, ages 15 – 24 (62%) and adults, 25- 39 (52%) engaging in heavy drinking during their reproductive years is of great concern. While the overall percentage of men engaged in heavy drinking (56%) is higher than women (37%), the gender division cannot be examined separately as male partners (as well as friends and sisters) tend to encourage drinking activity among women regardless of pregnancy status. In this report it is stated that the 2002 NT Drug and Alcohol Survey results when compared to the 2006 data, indicated that the frequency of alcohol consumption for those drinking during pregnancy has not shown a reduction. Additionally, the main reason for most mental health hospitalizations for both women (48%) and men (65%) were substance related disorders. This includes the abuse of alcohol or withdrawal from alcohol. Between 2003 and 2007, 39 NT residents committed suicide, for an overall average rate of 1.8 per 10,000 (population) per year (Northwest Territories, 2010, p.56) and reflective of a much higher proportion then the national average of 1.1 per 10,000 (population). These statistics in each area – alcohol consumption, mental health hospitalizations and health complications related to alcohol use, are interwoven. Alcohol is implicated in most episodes of violence and a large percentage of injuries in the North (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2007). The number of infants born with FASD is unknown as prevalence data is not yet tracked consistently across Canada.

Factor 3: The statistics on child welfare involvement and children receiving care from the government because of family problems and issues related to this intervention

Identifying child welfare concerns within this paper is important as it contextualizes concerns for children and families. Our society places the responsibility to protect and nurture children with biological parents/legal caregivers. While birth families may be involved in the support of their child with an FASD diagnosis, the reality is many find that the difficulties in their own lives, related to poverty, alcohol abuse, histories of trauma and housing instability, overwhelm the possibility of taking on such exceptional parenting. Caregivers representing the state such as foster or adoptive families quickly become engaged in the parenting process once children are removed from familial care. Child protection agencies are responsible for investigating all allegations of child abuse or maltreatment and intervening when necessary. This decision making process is the sharp edge of ethical reasoning, as removal of a child from their home is traumatizing. The standing concern of children with disabilities such as FASD and the ability of parents to respond to such needs becomes a factor in decision making. Involvement in child welfare is stigmatizing in the North, and less well hidden than in large urban cities. Additionally, agencies are mandated to provide support to families facing challenging circumstances in order to ensure the safety and wellbeing of children (North West Territories, 2010). The report states: “Children may receive services because they were abused or neglected. Other children may come into care voluntarily and/or receive services because they have unmanageable behavioral problems resulting from developmental delays, mental health issues or Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder”, (p. 70). Another concern noted in this report was that drug and solvent use was identified as a major factor in referrals for Child and Family Services.

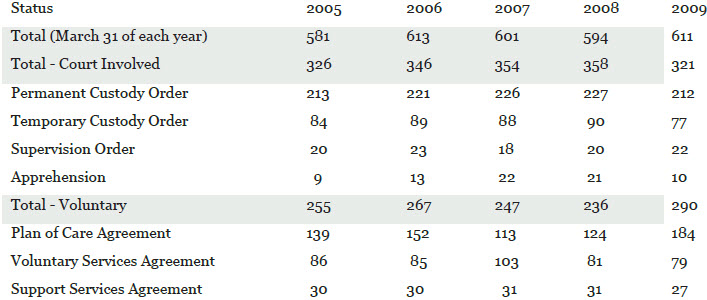

Table 1

The NWT report summarizes the involvement by child welfare in the territories

In 2009, according to the Northwest Territories (2010) Health Status Report, 611 children were receiving services and approximately 53% of these children (321) were receiving services through a court order (apprehension, permanent custody order, supervision order and temporary custody order), with the remaining 47% (290) receiving services through a family-based agreement (plan of care agreement, support services agreement and voluntary services agreement). This report suggests that parents having a drug or solvent problem have consistently been the top cause of CFS referrals in the NWT since 2004. The impact of child removal in small communities is direct. Foster care may not be available in the same community, or relocation may be necessary due to lack of local resources. In respect of Northern context and reality, cultural practices, such as Custom Adoption, are utilized when possible within families and communities. Underlying this practice is a broad based cultural intervention. When children from remote communities are subject to adoption, the practice of maintaining home ties wherever possible is important to the future of the community.

Across the provinces, and territories, a range of policies exist relating to the state’s role in supporting a healthy home life. However, the number of children either removed from the care of their parents or guardians or receiving Child and Family Services (CFS) in their own homes are indicators of these continuing crises (NWT, 2010). The NWT territorial government has started to consider policies looking at costs and outcomes. Factors such as poverty and lack of a consistent resource infrastructure across Northern communities are a reality that contributes to the above noted issues of child welfare involvement, alcohol abuse and trauma. The information presented in this paper regarding child welfare involvement is important, as child welfare interventions are deeply interwoven into grief and loss issues for children, families and communities. The need to identify interventions that are holistic and restorative is crucial in moving forward in FASD prevention and supports.

In Canada, governments generally provide services to children and families under an umbrella of provincial or territorial child welfare. While this has resulted in a broken road for Canadians who wish to relocate, and differing systems exist from province to province in relation to supports related to FASD, this structure provides a framework to examine these concerns. At present, only the Yukon has directly addressed the issue of FASD in its legislation (Children’s Act Revision, 2005). Alberta has developed an FASD 10-Year Strategic Plan, published in 2008, and suggests that all government ministries include priorities regarding FASD within their operational plans (Government of Alberta, 2008). One report that specifically calls for public policy development in relation to the social determinants of healthy pregnancy hails from British Columbia (BC). The report Understanding Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Building on Strengths reviews strategic initiatives as of 2003 in BC and outlines future plans and strategies strongly related to women’s health Child welfare involvement for families of children with FASD is a challenge because supports are needed to work with the child with disabilities and they do not always exist in small and remote communities. This has been identified as a concern by Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada (2010) in their environmental scan of services and gaps in Inuit communities. A common consensus from these reports and researchers is the need to develop capacity around diagnosis follow-up supports, awareness and interventions.

Discussion

Identifying three key factors that are prominent in the discourse about Northern social health is a critical step in providing a broader framework for prevention and intervention. The three factors; trauma, alcohol abuse and child welfare involvement, and the impact on communities in the northern territories of Canada are underlying foundations in any discussion on FASD prevention. The discourse and dialogue on prevention of FASD is somewhat fragmented in rural and remote communities across Canada, not just the North, for a number of reasons. In rural communities access to resources, such as diagnostic clinics, does not exist within the health care system in a similar fashion to communities in larger, urban centers. While efforts are made to refer for diagnosis – an important tool in planning interventions and effective supports for children and youth with FASD, families in the North are disadvantaged in accessing such resources. Responding to FASD as a health issue places it squarely within a health model and framework and hopefully resources will follow accordingly. While broad awareness exists of FASD as a public health issue the root causes of FASD identified within this paper warrant further examination.

An FASD research lens

The Canada FASD Research Network Action Team on Prevention developed a consensus statement for FASD prevention. One of the 10 fundamental components is being trauma-informed:

Multiple and complex links exist between experiences of violence, experiences of trauma, substance use, addictions, and mental health. It is important to understand that at times, research initiatives, policy approaches, interventions, and general interactions with service providers can in themselves, be re-traumatizing for women. When a woman seeks out treatment or support services, practitioners have no way of knowing whether she has a history of trauma. Trauma-informed systems and services take into account the influence of trauma and violence on women’s health, understand trauma-related symptoms as attempts to cope, and integrate this knowledge into all aspects of service delivery, policy, and service organization

CanFASD, 2013

In putting this model forward it is our hope that a deeper appreciation of history and context is considered in relation to intervention around FASD that is rooted in the experiences of women prior to giving birth to a child with FASD. The broader underlying issues of historical trauma that are not only rooted in women’s lives, but also in wider community histories should inform compassionate and caring responses to the prevention of FASD that are grounded and supported within community based circles of caring.

Conclusions

There are key areas that require a strong focus in prevention of FASD from a women’s’ social determinants of health lens such as maternal health. We did not directly report on the qualitative data in this article from the BOHF project that work has influenced this article and highlighted the need for a close look at relevant literature. It was abundantly clear that, to women participants, the well-being of their children is highly important as this was so often mentioned. For women struggling with addiction, counseling that supports a harm reduction framework must be considered. Women with addiction issues are exposed to a great deal of harm and experience a lack of safety, particularly women who are homeless in the NT and dealing with unresolved trauma.

A research agenda that examines FASD in the North is moving forward as projects that work within communities and support local networks are evolving with support from the Canada FASD Research Network. Engagement in this project has opened some dialogue and a body of literature is emerging on Inuit concerns related to FASD (See Appendix 1). Women who are supported to have healthier lives will benefit in all other areas of their life including maternal health. Other supports include urgent access to addictions treatment for alcohol and drugs as well as smoking reduction and cessation. Our model presented three factors, 1) trauma, 2) alcohol abuse and 3) child welfare involvement which underlie FASD prevalence, it is recognized that supportive and accessible resources in responding to each of these areas will have a broader impact of the physical, social and mental health of communities.

Future research on FASD prevention in the north should consider the impact of major changes in the identified factors. For example, child welfare systems based on extended family strengths could alter the perception of northern families when faced with government intervention. Social and political locations for information on FASD prevention should be examined in terms of community histories, and partnerships with education and health should be used to promote critical intervention models. The need for FASD prevention should be multifaceted, grounded in women’s and community health frameworks and supported in local, community based initiatives.

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix 1. Inuit specific resources

An important body of literature is emerging on this topic and identifies the need for Inuit specific social determinants of Health. Examples of research-based documents include:

Ajunngingiq Centre & National Aboriginal Health Organization. (2006). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: An environmental scan of services and gaps in Inuit communities. National Aboriginal Health Organization.

British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. (2007). Preventing FASD through providing addictions treatment and related support for First Nations and Inuit Women in Canada. British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. Retrieved from: www.coalescing-vc.org.

Cameron, E. (2011). State of the knowledge: Inuit Public Health 2011. 2011 National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, (NCCAH). The National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved online June 16, 2012 from: http://nccah.netedit.info/docs/setting%20the%20context/1739_InuitPubHealth_EN_web.pdf

Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. (2006). National strategy to prevent abuse in Inuit communities: Somebody’s daughter – On-the-Land workshop model. Online report: www.pauktuutit.ca

Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. (2010). Inuit women taking the lead in family violence and abuse prevention. (Unpublished paper).

Richmond, C. (2009). The social determinants of Inuit health: A focus on social support in the Canadian Arctic. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 68:5 2009.

Bibliography

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (1999). Aboriginal Healing Foundation program handbook, (2nd Ed.). Ottawa, Ontario: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Badry, D. (2012). Brightening Our Home Fires project Northwest Territories final report. Submitted to First Nations and Inuit Health Branch. Unpublished Article. University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

- Bartlett J.G., Madariaga-Vignudo L., & O’Neil J.D., Kuhnlein H.V. (2007). Identifying Indigenous peoples for health research in a global context: a review of perspectives and challenges. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 66(4), 281-376.

- Cameron, E. (2011). State of the knowledge: Inuit public health 2011. Prince George, British Columbia: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved online June 16, 2012 from: http://nccah.netedit.info/docs/setting%20the%20context/1739_InuitPubHealth_EN_web.pdf

- Canada Northwest FASD Research Network (2010). Consensus on10 fundamental components of FASD prevention from a women’s health determinants perspective. Retrieved from http://www.canfasd.ca/files/PDF/ConsensusStatement.pdf

- Caron, N. (2005) Getting to the root of trauma in Aboriginal populations. Canadian Medical Association Journal,172(8), 1023-1024.

- Chansonneuve, D. (2005). Reclaiming connections: Understanding residential school trauma among Aboriginal people. Ottawa, Ontario: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Chansonneuve, D. (2007).Addictive behaviors among Aboriginal People in Canada. . Ottawa, Ontario: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Child Education. (2005). Children’s Act revision- Prevention/early intervention policy forum paper. Retrieved from http://www.yukonchildrensact.ca/downloads/policyforum/Prevention-Intervention.pdf

- Connell, M., Novins, D., Beals, J., Whitesell, N. Libby, A., Orton, H., Croy, C. and AI-SUPERPFP Team. (2007). Childhood characteristics associated with stage of substance use of American Indians: Family background, traumatic experiences, and childhood behaviors. Published online 2007 August 6. Doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.012 . Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2447861/pdf/nihms32661.pdf

- Edmund, D. & Bland, P.J. (2011). Real tools: Responding to multi-abuse trauma – A tool kit to help advocates and community partners better serve people with multiple issues. Juneau, Alaska: ANDVSA Publishers. Retrieved from http://www.andvsa.org/home-page/real-tools-responding-to-multi-abuse-trauma/

- Fallot, R.D. & Harris, M. (2009. Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care (CCTIC): A self-assessment and planning protocol. Washington, DC: Community Connections. Retrieved from: http://www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/icmh/documents/CCTICSelf-AssessmentandPlanningProtocol0709.pdf

- Government of Alberta. (2008). Alberta FASD 10 year strategic plan. Edmonton, Alberta: Alberta FASD Cross Ministry Committee.

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2007). Social determinants of Inuit health in Canada. A discussion paper. Victoria, British Columbia: Aboriginal Health Research Networks Secretariat. Retrieved from: http://ahrnets.ca/files/2011/02/ITK_Social_Determinants_paper_2007.pdf

- LaRoque, E.D. (2001). Violence in Aboriginal communities. Ottawa, Ontario: National Clearinghouse on Family Violence. Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H72-21-100-1994E.pdf

- Ministry of Children and Family Development. (2008). Understanding Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder; Building on strengths: A provincial plan for British Columbia (2008-2018). Victoria, British Columbia: Government Printing Retrieved from http://www.mcf.gov.bc.ca/fasd/pdf/FASD_TenYearPlan_WEB.pdf

- North West Territories. (2010). Health status report. Yellowknife, Northwest Territories: Government of the Northwest Territories Press. Retrieved from http://www.hlthss.gov.nt.ca/pdf/reports/health_care_system/2011/english/nwt_health_status_report.pdf

- NWT Bureau of Statistics. (2002) Alcohol & drug survey. Statistical summary report. Yellowknife, Northwest Territories: Government of the NWT Press. Retrieved from http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/health/62412.pdf

- Pauktuutit – Inuit Women of Canada. (2010). Inuit five-year plan for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: 2010-2015. Ottawa, Ontario: Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada Press. Retrieved from http://www.pauktuutit.ca/health/

- Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. (2010). Inuit women taking the lead in family violence and abuse prevention. Retrieved from http://pauktuutit.ca/abuse-prevention/family-violence/taking-the-lead-in-family-violence-prevention/.

- Salmon, A. and Clarren, S.K. (2011). Developing effective, culturally appropriate avenues to FASD diagnosis and prevention in Northern Canada. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 70(4), 428-33.

- Wesley-Esquimaux, C. & Smolewski, M. (2004). Historic trauma and aboriginal healing. Ottawa, Ontario: The Aboriginal Healing Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/historic-trauma.pdf

List of figures

List of tables

Table 1

The NWT report summarizes the involvement by child welfare in the territories