Abstracts

Abstract

Research and practice wisdom tells us that women who themselves have FASD are at high risk of having concurrent substance use and mental health problems, and of having a baby with FASD. Despite this, there is a dearth of published information that has focused on the support needs of women with FASD who have substance use problems, or on effective practice in providing substance use treatment and care for women with FASD.

This article presents findings based on interviews with 13 substance-using women with FASD, which was a key facet of a three-year research project that had three inter-related components. The research also included a review of the literature regarding promising approaches to substance use treatment and care with women with FASD and interviews with multl-disciplinary service providers across British Columbia to identify promising and innovative programs, resources and approaches relating to substance use treatment for women with FASD. Highlighted are promising approaches and good practice and/or programs for women with FASD who have addictions problems, from the perspective of individuals most directly affected by the issues: women with FASD who have substance use problems.

Keywords:

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder,

- FASD,

- FASD Prevention,

- substance use treatment for women,

- promising practices

Article body

Introduction

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is an umbrella term used to describe a range of conditions and effects emerging from prenatal exposure to alcohol. FASD is a lifelong, invisible, physical disability with behavioural symptoms (Malbin, 2002). It gives rise to substantial physiological, cognitive, behavioural and social difficulties. Although the effects of FASD vary considerably there is tremendous heterogeneity in people’s strengths and in the nature and degree of the harms and disabilities experienced by those living with FASD.

FASD is the leading known preventable cause of developmental disability in North America (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2005). Currently, the estimated prevalence rate of FASD in North America is 9.1 per 1000 live births (Motz, Leslie, Pepler, Moore & Freeman, 2006; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2005). At the same time, recent literature emphasizes the difficulties in obtaining accurate population-based prevalence rates. In particular, methodological flaws have been noted in prevalence studies involving certain populations, including Aboriginal peoples (Roberts & Associates, 2007).

In considering FASD within Aboriginal populations, Dell and Roberts (2006, 26) raise the issue that “Canadian studies on women’s use of alcohol during pregnancy, in particular in relation to FAS and FASD, disproportionately focus on Aboriginal women and the geographic areas in which they live”. Further, Tait (2003, 2009) and Hunting and Browne (2012) have noted that this disproportionate focus can result in heavily skewed data on the purported prevalence of FASD within both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations. In fact, it has been demonstrated that there are very few epidemiological studies on the issue, and what data are available often are either high flawed methodologically or not disaggregated by sex (Pacey, 2009; Poole, Gelb & Trainor, 2008).

Rutman and Van Bibber (2010, 352) have emphasized the need to discuss FASD within its colonial context, and as well, within the context of (re)connecting to traditional knowledge and practices. They state:

In Aboriginal communities…FASD finds its roots in the colonial history of Canada. Colonization, racism and the deterioration of First Nation political and social institutions, the suppression of traditional spirituality, culture and language, the apprehension of children and loss of traditional lands and economies is the legacy of Canada’s settler history (Van Bibber, 1997). The residential school system proved extremely effective in destroying cultural pride and self-identity, in obliterating connections with traditional languages and in disrupting and severing family relationships (Tait, 2003). The current health and socio-economic conditions trace their beginnings to these historic events. What is less obvious when addressing issues such as FASD is the rich culture that existed before colonization, a culture so vibrant that its distinct nature lives on today.

In keeping with this, Dell, Acoose, and their colleagues, have spoken of the ways in which culture and cultural (re)connection are themselves healing ‘interventions’, and about the importance of ensuring that these ‘interventions’ are conceptualized and practiced within cultural contexts (see, for example, Dell et al, 2011; Dell & Acoose, 2008).

Currently, we do not have conclusive evidence regarding the likelihood that people who have FASD will have problematic substance use issues. However, the literature suggests that a disproportionate number of people with FASD will have substance use problems (Streissguth, Barr, Kogan & Bookstein, 1996). In addition, research has shown that women who have FASD are at high risk of having concurrent substance use, violence and trauma experiences, mental health problems, and of having a baby with FASD. Along these lines, one landmark study profiled 80 women who had children diagnosed with FASD. Of these 80 women: 100% had been abused; 90% had serious mental health issues, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; 80% lived with partners who did not want them to stop using substances; and approximately 50% had FAS conditions themselves (Astley, Bailey, Talbot & Clarren, 2000).

Given the reality that some women with FASD may also have substance use problems, combined with the likelihood that women with FASD are sexually active, it is not improbable that women with FASD may use alcohol or drugs while pregnant. Thus, from the perspective of FASD prevention, women with FASD need to be viewed as a group warranting particular attention.

Despite this, relatively little is known about women with FASD and their experiences in relation to substance use, in their attempts to access care related to their substance use, and in terms of what is good practice and promising substance use treatment programming for women with FASD. Without knowledge about good practice in working with women with FASD, it is very difficult to offer tailored and responsive services that provide effective prevention and treatment. Thus, it is critically important for practitioners, managers, program developers, policy makers, researchers, along with community support people to increase and apply knowledge about good practice in working with women who may have FASD.

To address this knowledge gap, the overall purpose of the Substance-Using Women with FASD & FASD Prevention project was to expand knowledge regarding effective, appropriate substance use treatment approaches for women living with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. A key facet of our project was giving voice to substance using women with FASD regarding their views on ‘what works’ and what were the most helpful approaches employed within programs and by service providers, community resources and/or other support people (see Rutman, 2011b for the full report based on this component of the project). Additional components of this project were: a comprehensive review of the Canadian and international literature regarding promising practices in substance use treatment and care for women with FASD and semi-structured interviews with 40 multi-disciplinary service providers across British Columbia regarding innovative and promising programs, resources and approaches related to substance use treatment and care for women with FASD (see Gelb & Rutman, 2011, and Rutman, 2011a for reports based on these project components).

This article focusses on sharing the findings emerging from women’s perspectives in relation to promising approaches; as well, this article integrates these findings with the results arising from the other two components of our project. We conclude by sharing a wholistic framework for conceptualizing FASD effects and FASD-informed approaches that has emerged from our research and from subsequent interactive knowledge exchange events with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal multi-disciplinary practitioners, program planners, policy makers, families, and people living with FASD. Indeed, in view of the far-reaching implications and applications of our findings and the emerging framework, we believe that this article has direct relevance for multiple and diverse audiences – practitioners, managers, policy makers, educators, researchers, community-based support people and advocates, and those living with FASD.

Research process

In keeping with research exploring people's lived experiences, the project employed a qualitative research design; as well, the research was informed by critical and participatory methods whereby those who had direct experience with the focal issues were centrally involved in the research process, as members of the project’s advisory committee, as project partners, and as part of the research team. A hallmark of these methodologies is the belief that participants' experiences and standpoints are the starting point and core of the inquiry (Barnsley & Ellis, 1992). These approaches also emphasize the importance of giving voice to those whose voices are often unheard.

For this component of the project, in-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted with a total of 13 women with (suspected) FASD. In keeping with a number of qualitative methodologies, we employed theoretical (i.e., purposeful) sampling techniques whereby emphasis is placed on selecting appropriate, "information-rich cases" for in-depth study (Morse, 1994; Sandelowski, 1986). Research participants were both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women and came from four diverse communities in British Columbia.

Participants

Eligibility criteria for participation in the interviews were that participants were women who:

had a substance use problem, or were birth mothers of a substance-exposed child, and

self-reported having been prenatally exposed to alcohol or that their birth mother had alcohol use problems, or

were assessed/diagnosed and/or self-identified as having FASD, or

were raised by someone other than their birth parents and were identified by service providers or support people as having behaviours or characteristics in keeping with FASD.

Our project advisors – in particular, those who were staff of programs and organizations serving women with substance use problems – provided assistance in identifying a potential sample of interview participants. All women invited to participate in the project were current or former participants of community-based programs that were either specifically geared to people living with FASD or were for substance-using pregnant or parenting women.

In keeping with other studies focussing on issues for adults living with FASD, we did not require a diagnosis/assessment of FASD as a criterion for participation. This is because the majority of people living with FASD have not had a formal diagnosis. To ignore those who lack a diagnosis would be to further marginalize and dismiss the experiences of those living with FASD.

Nevertheless, during the course of our study, three women had received an FASD-related diagnosis (i.e., ARND; partial-FAS) following their involvement in an adult FASD diagnostic clinic, and all women either self-identified as having had been prenatally exposed to alcohol or identified with receiving services or care related to adults or families living with FASD.

The 13 women participating in the interviews ranged in age from their mid 20s to their early 50s. Four of the women (31%) identified as being of Aboriginal heritage, and nine women (69%) were Caucasian.

Interview process

The semi-structured interviews were carried out as guided conversations about people’s lives and experiences. The interview guide was created in partnership with substance-using women and was pilot tested with two women who had been assessed as having FASD.

The interviews were open-ended and began with an invitation for the woman to tell their story or share anything about their history and/or current life circumstances, including their current living situation, their family and children, their involvement in raising their children, and their use of and/or difficulties with alcohol or drugs. The interview then focused on four primary questions: 1) What were women’s positive experiences in substance use treatment and/or what had worked well for women in their experiences with services, and in particular with substance use treatment programs; 2) what hadn’t worked well; 3) what would help improve substance use treatment programs; and 4) what were any other areas in the women’s lives in which they needed help or support.

Interviews ranged from 30-90 minutes in duration and were carried out in a private location of the participant’s choice. Interviews were either audiotaped with participants’ consent, or extensive notes were taken, with every effort made to record participants’ words verbatim. Participants were offered an honorarium in recognition of their time in taking part in an interview.

Findings

This article focuses on findings related to ‘what works’ and what are helpful and useful substance use-related programs, practices and approaches from the perspective of substance-using women with FASD. We begin, however, by sharing findings related to women’s self-descriptions of themselves and their ‘story’, including their use of alcohol or drugs and how their substance use and FASD intersected with other areas of their lives.

Women’s lives: Situating substance use and prenatal exposure to alcohol

Women as mothers

While each woman had a unique story, there were a number of important commonalties in their experiences. Foremost among these was that 12 of the 13 women were mothers, and their lives as mothers figured extremely prominently in their self-descriptions.

Beyond this common experience, however, there was variability; the number of children that each woman had and the children’s ages varied considerably. Similarly, the children’s health and their developmental and behavioural issues varied substantially. Although some women’s children were “typical” from a neuro-developmental perspective, several women had at least one child who had an invisible disability such as FAS, FASD or Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Further, all 12 mothers had had some type of involvement with child welfare authorities, and all had had at least one child or children removed from their care for at least some period of time. At the same time, there was considerable variability in terms of whether the women had retained custody of one or more of their children and whether the women were in the midst of, or had been through, the process of attempting to regain custody of their child(ren).

Women as survivors of violence, trauma abuse, trauma, and related health issues

Nine of the 13 women participating in our study reported being survivors of violence, abuse and/or trauma in their childhood and/or adulthood. (It is important to note, however, that the women were not specifically asked whether they had these types of experiences. Thus, it is possible that other women experienced violence or trauma but did not volunteer this information as part of the interview. The women shared information relating to violence or abuse in response to an open-ended invitation to talk about themselves at the beginning of the interview and/or as part of talking about their needs in broad areas of their life.)

In addition, all of the women reported serious mental ill-health issues such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, which they linked to the violence or abuse they experienced and/or to residential school experiences and related disconnection from culture, community and family. Further, several women spoke of experiencing feelings of intense anger and hopelessness following the removal of their children by child welfare authorities, as well as their feelings of shame or guilt related to having exposed their child(ren) prenatally to alcohol or other substances.

From a social determinants of health perspective, other key issues in the women’s stories and self-descriptions were: their ongoing deep poverty; their difficulties in finding and keeping safe, affordable housing; challenges in accessing adequate child care; difficulties in finding employment; difficulties in maintaining healthy non-abusive relationships with their partners; difficulties in accessing mental health-related services and supports; and struggles with parenting, particularly if their child(ren) had a neuro-developmental disability.

Women as having Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

In terms of discussing having FASD, 10 of the 13 women shared information about their mother drinking heavily during pregnancy or generational substance use. Four of these women shared that they believed they had FASD. Nevertheless, none reported having been formally assessed or diagnosed with FASD. This is noteworthy given that, as stated in the Research Process section, three of the women had been involved in an adult FASD diagnosis clinic at the same time that they participated in the research interview for this project, and they had in fact received a diagnosis related to FASD. That these women did not disclose their having a diagnosis is indicative of one or more possibilities, including that their difficulties with memory and/or information processing interfered with their recollection or comprehension of the assessment results, they did not see the relevance of disclosing the assessment results in our interview, and/or they felt embarrassment, shame or a sense of stigma in relation to the assessment results and a diagnosis related to FASD.

Contextualizing women’s substance use

Many of the women linked their problematic use of alcohol or drugs to their experiences of violence, abuse and trauma, their sense of hopelessness regarding their children’s removal from their care, and their sense of disconnection from family, community and culture. One Aboriginal woman stated, “I wasn’t prepared for that disconnect [from community]. It brought my soul down…and alcohol became heavier, and I started to lose my identity and family.” This woman also linked her ongoing substance use to trauma related to residential school experiences: “Residential was part of that in my life also. I found out later, when I did treatment, that that was, at core, why the behaviour continued.” Other important themes relating to the context of women’s substance use were the influence of the woman’s partner and the degree to which substance use appeared to the woman as being “normal” within her family or community. Along these lines, women also shared stories of how their partner’s lack of support for their efforts to obtain services, or conversely, a partner’s commitment to quitting made a pivotal difference in the success of their efforts to reduce their use.

In sum, what emerged from women’s self-descriptions - even prior to their discussion of their experiences with substance use treatment and other programs and services - was their experience of multiple issues and struggles, of which their substance use (during pregnancy) was only one. The women did not compartmentalize their substance use (or any other single issue in their lives), and thus, substance use programming must see the whole woman and place women’s substance use within the context of their lives and day-to-day realities.

What works – Women’s positive experiences in receiving services

A number of themes emerged in response to the question of what had been helpful in women’s experiences with programs and services, and what ‘worked’ in assisting them to quit or reduce their problem alcohol or drug use. These themes included both helpful approaches and aspects of the support received from a service provider, family member or partner, and identification of particular programs or resources that were reported to be especially effective.

The themes in women’s discussion included:

Women’s readiness for change is crucial; thus, working with women “where they are at” is vitally important

A relationship-based, culturally safe approach is key

Wholistic and integrated programs are most useful

One-to-one support from a skilled professional combined with women-centred, peer-based support is most effective

Flexibility in extending the program’s duration is helpful

Service providers being knowledgeable about FASD is essential

It is important to note that a number of the programs reported by women to have been helpful were not actual substance use treatment programs. Instead, they were personal development, employability or mothering-mentorship programs guided by a wholistic framework that recognized that women seeking support often had multiple issues that needed to be addressed in an integrated way. Additional discussion of the first three of the above themes follows.

Readiness for change

Nearly all of the women interviewed emphasized the importance of being ready to make a change in their life and in relation to their substance use. Indeed, from women’s perspective, their genuine readiness for change was what distinguished their successful experience of reducing or quitting their problematic substance use from other experiences or instances when they tried to quit or entered treatment programs but in fact were not ready. One woman thus noted that “being ready” trumped court-ordered programs if readiness was not present: “For myself, I feel that you have to be ready. You have to be ready, and if you’re not ready for it, it’s a waste of people’s time and your time. Because you just get to the point where you need to do something. Court orders just don’t do it.” Another woman similarly stated, “Getting the help was easy – staying clean was hard. When I was ready, the help was there.”

Further, for the majority of women taking part in our interviews, readiness for change and for reducing or quitting alcohol or drug use was related to either their pregnancy or their efforts to regain care or custody of their child(ren). Indeed, for some, pregnancy and desire for their baby’s good health triggered their recognition that they were ready to quit using alcohol or other substances. In one woman’s words, “I wasn’t ready at the beginning. Then found out I was pregnant, and I knew I was ready.”

Relational, culturally safe approach

All women interviewed spoke clearly and emphatically about this point: “what works” and what was foundational to their positive experiences in programs was their having a trusting, honest, respectful and caring relationship with a service provider or support person, wherein they felt safe and did not feel judged, blamed or shamed.

“[The mentoring program] was unique. Women came because they felt safe. We learned so much and felt so safe. These women learned to trust and it was fantastic.”

“They didn’t shame me at the Centre. Took me though my history and helped me to understand why. Try to build your self-esteem along the way.”

Service providers’ understanding of the complexity of the issues and practical support needs facing substance-using women and women living with FASD was also clearly valued by women.

I had support from Metis Services. A man who worked there was awesome. He really cared about me. A child care social worker was also very helpful – he really understood FAS. ….I don’t think I would be nearly where I’m at if it wasn’t for them. They genuinely cared; they had a lot of knowledge, compassion and personal experience.

Along similar lines, women expressed deep appreciation for service providers who conveyed their confidence in the women’s ability to make changes in their life and who didn’t “give up” on them, even if they had setbacks that impeded their progress in achieving their goals.

He had faith in me. I kept screwing up, but he kept supporting me. Even though he was tough, I have a lot of respect for him.

Wholistic and integrated programs

As discussed in the preceding section, the women interviewed for this study did not compartmentalize their substance use problems and related needs for services or support as being unrelated to the other areas in their life in which they needed assistance. Thus, from their perspective, ‘what worked’ best were multi-faceted participant-centred programs that approached women’s lives and needs wholistically, as well as programs that were well coordinated or integrated with other services or resources serving women.

For example, several of the women participating in interviews had been involved with, and were extremely positive about, a mothering-focused program that, in addition to offering peer mentoring related to mothering, also offered one-to-one support from a skilled counsellor who assisted women with their individual issues in the areas of housing, tenancy, financial literacy, employment-readiness, and life skills, and safety in relationships. As one woman stated:

Support, support, support from non-government people who understand how important practical support is. Getting a phone bill paid, a grocery voucher, daycare so we can go to meetings. Help in raising FASD kids – or any kids – having FASD is tough – my house is filthy – I don’t know how to clean – I barely get my kids to school. [The program facilitator] used to get me a housekeeper and someone to help me manage my life.

As indicated by this comment, and underscoring a point discussed above, along with women’s appreciation of programs that were wholistic and flexible was their valuing of programs and program staff that had a strong understanding of FASD and the needs of children and adults living with FASD.

Discussion

The findings presented in this article were based on community-based interviews with four Aboriginal and nine non-Aboriginal substance-using women who had or were suspected of having FASD; the study was not limited to Aboriginal women with (suspected) FASD. These interviews comprised one of the three components of the Substance-Using Women with FASD and FASD Prevention project. The other two components were interviews 40 multi-disciplinary service providers working with women with substance use problems or at risk of having a baby with FASD, and a comprehensive literature review aimed at identifying promising approaches to substance use treatment and care for women with FASD.

In our qualitative interviews, women were able to share their story in their own words. At the same time, the interviews largely focused on: women’s positive experiences in substance use treatment and/or other types of programming and/or what they believed had been helpful in relation to dealing with their problem alcohol or drug use; what hadn’t worked well; and what, based on their experience, would help improve substance use treatment programs and care.

While women’s stories and experiences were as varied as the women themselves, emerging at the core of their self-descriptions were several common, inter-connected themes, including: being mothers; being survivors of abuse and trauma, and living in highly fragile domestic relationships in which they were vulnerable physically, emotionally and/or financially; having mental health issues and needs related to their experiences of abuse and trauma; struggling to find stable, safe housing for themselves and their children; living in deep poverty and continually struggling to find ways to make ends meet; being entangled with and at times feeling vulnerable or vigilant in relation to the child welfare system; and having problem substance use which typically exacerbated their involvement with child welfare authorities. Notably, having FASD was not generally a key aspect of women’s descriptions of themselves.

Also notably, the life experiences and self-descriptions of the women in our study paralleled those reported elsewhere in the literature, including in key research on characteristics of biological mothers of children with FASD (e.g., Badry, 2008). For example, one landmark study found that of the 80 birth mothers whose children were undergoing assessment for FASD, nearly 100% were survivors of physical or sexual abuse and had serious mental health issues, and roughly 50% of these women reported being prenatally exposed to alcohol themselves (Astley et al, 2000).

The women’s self-descriptions are an important starting place for consideration of key lessons for practice, service planning and policy. Foremost among these is that those planning and providing care to women with FASD need to adopt a wholistic approach and understand women’s substance use within the context of all facets of their life and community contexts. While this finding may not seem new or surprising – indeed, the importance of a wholistic approach in working with substance using pregnant or parenting women has been consistently emphasized as best practice in the literature for years (Motz et al, 2005; Niccols & Sword, 2005; Parkes, Poole, Salmon, Greaves & Urquhart, 2008; Poole, 2011), our interviews with women with FASD underscores the urgency of this approach.

A second key lesson is that women with FASD most likely will not self-identify as having a neuro-developmental disability, especially in the initial stages of program intake. Thus, program staff and managers need to be attuned to the likelihood that some of the women with whom they are working may have FASD. Further, this means that service providers must be knowledgeable about FASD and its behavioural characteristics, as well as about the range of program-related adaptations and accommodations that are key to removing barriers to access and to promoting women’s success within services.

In terms of promising approaches to substance use treatment, the themes emerging from our interviews with substance using women with (suspected) FASD were both consistent with the existing literature on women-centred care and also helped us to further delineate key practices that were specifically informed by an FASD-lens and made a positive difference for women with FASD.

Women spoke clearly and passionately about the value of a trusting relationship with a service provider wherein they felt safe, could speak honestly and get honest guidance in return, and were not judged, blamed or shamed. This relational approach dovetails with the need to work with women where they are at and to tailor support and interventions in keeping with women’s readiness for change and their needs in various areas of their life – i.e., additional promising approaches in working with women with FASD include a need to focus on women’s readiness for change and thus the use of motivational interviewing techniques, albeit adapted for women with FASD (Dubovsky, 2009; Grant et al. 2009) as well as a wholistic and women-centred approach to services and care (Network Action Team on FASD Prevention from a Women's Health Determinants Perspective 2010a; Network Action Team on FASD Prevention from a Women's Health Determinants Perspective 2010b).

Synthesis of findings across our project’s three components

Although this article has focused exclusively on findings from our interviews with women with (suspected) FASD, the promising approaches that emerged from these interviews were highly congruent with our findings from the other components of this project – i.e., with the findings from our literature review and our interviews with service providers (Gelb & Rutman, 2011; Rutman, 2011).

Indeed, when the project’s findings were synthesized, what emerged was a set of promising approaches that led off with emphasizing the pivotal importance of mandatory training in FASD, along with ongoing mentoring and supervision, for service providers, managers and students involved in alcohol and drug counselling, clinical counselling, mental health services, social work and child welfare, and other human service professions. Further, an important promising practice identified in relation to training was that it take into consideration the support needs of the practitioner learners, who themselves may have experienced violence, trauma and problematic substance use (Gelb & Rutman, 2011; Rutman, 2011).

Other key promising practices delineating elements of an FASD-informed approach included: adapting the program’s physical environment to promote a calming and welcoming space (e.g. reducing noise levels or visual clutter); making program-related ‘accommodations’ to help ensure participation and successful program outcomes (e.g. reminder calls and transportation assistance; consistency in program timing; flexibility for late arrivals or missed appointments; extended timeframes for program duration; and flexibility and/or adaptations in group programming and process); adapting communication and motivational interviewing techniques; employing wholistic and collaborative approaches to programming (e.g., family-accessible programs and/or child care resources; collaborating with child welfare services to address issues related to child protection; liaising with supportive housing options; peer-based support and mentoring); and resourcing programs adequately to enable “care for the caregiver” such as smaller case loads and service provider supervision and support.

Conclusions and directions for change

By way of conclusion, we emphasize that substance use treatment programs serving women with FASD need to be designed and implemented using both FASD-informed and women-centred theoretical frameworks. It is the braiding together of the FASD-lens and the gender-lens that gives rise to promising and appropriate approaches for women who have FASD.

In working with women with FASD, professionals must have a clear understanding of each woman’s life circumstances and her social and cultural context, including her strengths, experiences, needs, readiness for change, and the barriers she may have faced in accessing or participating in services in the past.

To date, the predominant frameworks for conceptualizing the behavioural characteristics, issues/difficulties, needs and strengths of people with FASD have been guided by disability-focused or neuro-behavioural paradigms (Malbin, 2002; 2011; Streissguth et al, 1996). These frameworks have significant value, particularly in informing and reminding professionals, policy makers, families and community members alike that FASD is a brain-based, invisible disability, and thus the onus lies with all of us to (re)interpret behaviours and shift expectations accordingly (Malbin, 2012; 2011).

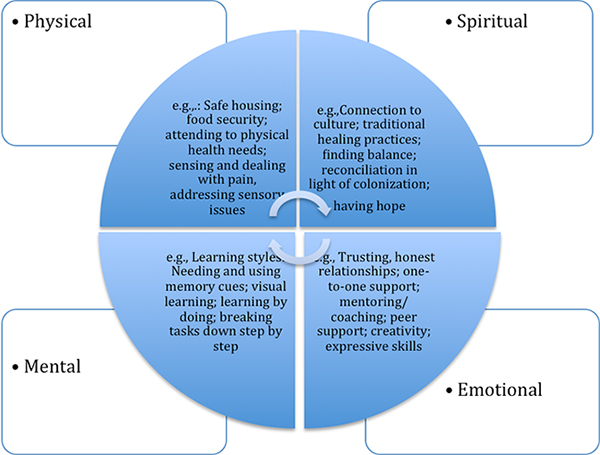

At the same time, our project’s findings and their implications have led us to develop and put forward another framework for conceptualizing both FASD effects and FASD-informed approaches; this framework is shown in Figure 1. At the core of this framework is the guiding value of being wholistic and of recognizing FASD-related strengths, goals, needs, and challenges across multiple dimensions, including physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually. A framework such as this one could also be used to explore possible FASD effects and FASD-informed approaches from the perspective of the individual, family, community and nation, and over different points in the lifespan and into future generations.

Figure 1

FASD-Effects, FASD-informed Approaches Considered Wholistically

We suggest that a wholistic, wheel-based framework such as this one is not at odds with a neuro-behavioural model; indeed, the different frameworks may be seen as being complementary. The value of a wheel-based framework, however, may be its ability to reflect and weave together multiple ways of considering the strengths, experiences and support needs of people living with FASD, and also understanding FASD within different cultural contexts, including traditional Aboriginal contexts that recognize the inseparability of different domains of health, spiritual knowledge and practices, and well-being (Chansonneuve, 2005; Van Bibber, 1997). Indeed, the circular framework depicted in Figure 1 is congruent with and has been informed by Indigenous wheel-based frameworks of well-being that emphasize the inter-connectedness of all aspects of existence, phases of the lifespan and future generations, as well as the importance of wholistic approaches to healing and understanding (Kryzanowski & McIntyre, 2011). Further, since both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women in our project spoke of the value of wholistic programming and care, this framework is suggested as a universal approach in working with both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women and individuals living with FASD and their families.

Finally, the wheel-based, wholistic framework also may remind us of the pivotal need for other key values, such as compassion, respect and collaboration, which, as demonstrated by women’s voices, are at the core of FASD-informed care.

Appendices

Bibliography

- Astley, S. J., Bailey, D., Talbot, C., & Clarren, S. K. (2000). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) primary prevention through FAS diagnosis: II. A comprehensive profile of 80 birth mothers of children with FAS. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 35(5), 509-519.

- Badry, D. (2008). Becoming a birth mother of a child with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (AAT NR38199)

- Barnsley, J. & Ellis, D. (1992). Research for change: Participatory Action Research for community groups. Vancouver: The Women's Research Centre.

- Dell, C.& Acoose, S. (2008). Girls, women and substance use. Waskesiu: Saskatchewan Prevention Institute FASD Speakers Bureau.

- Dell, C. A., & Roberts, G. (2006). Research update, alcohol use and pregnancy: An important Canadian public health and social issue. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Dell, C., Seguin, M., Hopkins, C., Tempier, R., Duncan, R., Dell, D., Mehl-Madrona, L. & Mosier, K. (2011). From benzos to berries: How treatment offered at an Aboriginal youth solvent abuse treatment centre highlights the important role of culture. In Review Series. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 56(2), pp. 75-83.

- Dubovsky, D. (2009). Adapting motivational interviewing for individuals with FASD: Applications in addictions and other treatment settings. In Third International Conference on FASD. Victoria, BC.

- Gelb, K. & Rutman, D. (2011). Substance using women with FASD and FASD prevention: A literature review on promising approaches in substance use treatment and care for women with FASD. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria.

- Grant, T., Whitney, N., Huggins, J & O'Malley, K. (2009). An evidence-based model for FASD prevention: Effectiveness among women who were themselves prenatally exposed to alcohol. Paper read at The 3rd International conference on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Integrating Research, Policy and Promising Practice Around the World: A Catalyst for Change, March 14, at Victoria, BC.

- Hunting, G. & Browne, A. (2012). Decolonizing policy discourse: Reframing the ‘problem’ of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Women’s Health and Urban Life, 11(1): 35-53.

- Kryzanowski, J. & McIntyre, L. (2011). A holistic model for the selection of environmental assessment indicators to assess the impact of industrialization on Indigenous health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 102(2), 112-117.

- Malbin, D. (2002). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome/ Fetal Alcohol Effects: Trying differently rather than harder, 2nd Edition. Portland, OR: FASCETS.

- Malbin, D. (2011). Fetal Alcohol/neurobehavioral conditions: Understanding and application of a brain-based approach – A collection of information for parents and professionals. Portland, OR: FASCETS.

- Morse, J. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

- Motz, M., Leslie, M., Pepler, D., Moore, T., & Freeman, P. (2006). Breaking the cycle: Measures of progress 1995 – 2005. Special Supplement Journal of FAS International,4:e22. Toronto, Hospital for Sick Children.

- Network Action Team on FASD Prevention from a Women's Health Determinants Perspective. (2010a.) 10 fundamental components of FASD prevention from a women's health determinants perspective. Vancouver, BC: Canada Northwest FASD Research Network and BC Centre of Excellence for Women's Health. Available from http://www.canfasd.ca/files/PDF/ConsensusStatement.pdf.

- Network Action Team on FASD Prevention from a Women's Health Determinants Perspective (2010b.) Taking a relational approach: The importance of timely and supportive connections for women. Vancouver, BC: Canada Northwest FASD Research Network and BC Centre of Excellence for Women's Health. Available from http://www.canfasd.ca/files/PDF/RelationalApproach_March_2010.pdf.

- Niccols, A., & Sword, S. (2005). “New Choices’’ for substance-using mothers and their children: Preliminary evaluation. Journal of Substance Use; 10(4): 239–251.

- Pacey, M. (2009). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder among Aboriginal Peoples: A review of prevalence. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

- Parkes, T., Poole, N., Salmon, A., Greaves, L. & Urquhart, C. (2008). A double exposure: Better practices review on alcohol interventions during pregnancy. Vancouver: BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health.

- Poole, N. (2011) Bringing a women’s health perspective to FASD prevention. In E. Riley, S. Clarren, J. Weinberg, & E. Jonsson (Ed.), Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Management and policy perspectives of FASD (pp. 161-173). Wiley-Blackwell, Weinheim, Germany.

- Poole, N., Gelb, K & Trainor, J. (2008). Substance use treatment and support for First Nations and Inuit women at risk of having a child affected by FASD. Vancouver, BC: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women's Health.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2005). Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): A framework for action. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Roberts, G. & Associates. (2007). A document review and synthesis of information on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Atlantic Canada. Report prepared for the Public Health Agency of Canada, Atlantic Region, and Health Canada, Atlantic Region - First Nations and Inuit Health.

- Rutman, D. (2011a). Service providers’ perspectives on promising approaches in substance use treatment and care for women with FASD. Victoria: University of Victoria.

- Rutman, D. (2011b). Substance using women with FASD and FASD prevention. Voices of women with FASD: Promising approaches to substance use treatment and care. Victoria: University of Victoria.

- Rutman, D. & Van Bibber, M. (2010). Parenting with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8, 351-361. DOI 10.1007/s11469-009-9264-7.

- Sandelowski, M. (1986). The problem with rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science, 8(3), 27-37.

- Streissguth, A., Barr, H., Kogan, J. & Bookstein, F. (1996). Understanding the occurrence of secondary disabilities in clients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE). Edited by A. Streissguth. Seattle: University of Washington, School of Medicine.

- Tait, C. (2003). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome among Aboriginal people in Canada: Review and analysis of the intergenerational links to residential schools. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Tait, C. (2009). Disruptions in nature, disruptions in society: Indigenous peoples of Canada and the ‘making’ of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. In L. Kirmayer & G. Valaskaki (Eds.). Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada (pp. 196-222).Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Van Bibber, M. (1997). Van Bibber, M. (1997). It takes a community: A resource manual for community-based prevention of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Fetal Alcohol Effects. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, and the Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada.

List of figures

Figure 1

FASD-Effects, FASD-informed Approaches Considered Wholistically