Abstracts

Abstract

Manifold representations of the dwelling are expressed in the work of artist, poet, writer, editor, and activist Alootook Ipellie in the bi-monthly publication Inuit Today in the 1970s and 1980s, as a cross-section through key moments in Inuit Nunangat history. This essay thus examines Ipellie’s representations of space—not as an attempt to theorize Inuit space but rather to offer reflections on how these representations challenged ways of knowing and interpreting Arctic communities. We first address the Arctic representation in Ipellie’s work, which emphasizes the existing richness of the land according to Inuit perspectives as opposed to Qallunaat (non-Inuit) interpretations. His drawings also offer political comments on land disputes and the exploitation of territory. We then explore the representation of buildings, as Ipellie witnessed the transition from traditional to government housing. Ipellie’s humour-based approach constituted a strong social and political critique of housing issues and settler-colonial building practices. This artist acknowledged Inuit ingenuity when speaking of traditional housing, thus advocating for Inuit knowledge, invention, and built heritage. Lastly, we discuss the representation of multiple voices in the struggles over space, including Inuit communities and non-human agents, such as animals and land. Dwelling on the notion of “lines” and “the in-between”, we consider the thickness of Ipellie’s drawn lines and attend to the multiple entanglements between the artist’s political cartoons and the many lines of settler-colonialism, such as boundaries, frontiers, roads, pipelines, spatial construction, buildings, and planning.

Keywords:

- Activism,

- Alootook Ipellie,

- Arctic,

- Land,

- Lines,

- Representation,

- Settler-Colonialism

Résumé

Cet essai examine les représentations de l’habitation dans l’oeuvre de l’artiste, poète, écrivain, éditeur et activiste Alootook Ipellie. Analysant tout particulièrement son travail publié entre les années 1970-80 dans le magazine bimensuel Inuit Today, cet essai accorde une attention particulière à la spatialité dans le travail d’Alootook Ipellie. Cet essai n’est pas une tentative de théoriser l’espace inuit mais plutôt une série de réflexions sur la manière dont les illustrations d’Ipellie défient les façons de connaître et interpréter l’Inuit Nunangat. L’essai aborde d’abord le portrait de l’Arctique dans l’oeuvre d’Ipellie qui exprime la richesse existante du territoire plutôt que l’espace en tant que potentiel conteneur d’infrastructures coloniales. Les dessins examinés explorent les conflits territoriaux et l’exploitation de l’environnement. Deuxièmement, la représentation des bâtiments y est étudiée dans la mesure où Ipellie a assisté à la transition du mode de vie nomade à l’intervention de l’état sur l’habitat et les questions sociales. Son approche humoristique constitue une forte critique sociale et politique sur les problèmes de logement et les pratiques de construction. Ipellie célèbre la sagesse de ses ancêtres en abordant l’habitat traditionnel, plaidant ainsi pour les connaissances et l’inventivité inuit. Troisièmement, l’article examine la représentation de multiples voix dans les débats autour du territoire dont celles des communautés Inuit mais également des non-humains, y compris les animaux et la terre. S’appuyant sur la notion de « lignes » et sur « l’entre-deux », l’article explore les enchevêtrements de lignes des caricatures politiques d’Ipellie, mais également des tracés du colonialisme tels que les frontières, routes, oléoducs, bâtiments, infrastructures, relevés et plans.

Mots-clés:

- Activisme,

- Alootook Ipellie,

- Arctique,

- territoire,

- lignes,

- représentation,

- colonialisme

Article body

Alootook Ipellie was born in 1951 in Navuqquq, a camp located near Frobisher Bay (now known as Iqaluit) in southern Baffin Island. At the age of four, he moved with his family to Iqaluit, where he spent his childhood and teenage years, thus experiencing the transition from the nomadic Inuit way of life to a government village settlement (Ipellie 1993). At sixteen, at the recommendation of federal government-appointed vocational counsellors, he moved to Ottawa to study a trade. Hoping to become an artist, Ipellie enrolled in a four-year vocational arts course but dropped out of the program after two years. After returning to Iqaluit, he worked for CBC as a reporter, then took a lithography course at the West Baffin Eskimo Coop in Cape Dorset. He briefly went to study in Yellowknife and later worked at CBC Radio in Iqaluit as an announcer-producer. In 1972, Ipellie began to work for the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (which translates as “Inuit will be united”), a political organization formed in 1971 by seven Inuit community leaders who sought to create a national Inuit organization that would voice shared concerns among Inuit about the status of land and resource ownership in Inuit Nunangat. Ipellie Alootook was first hired as a typist and translator for the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami newsletter, Inuit Monthly, which later morphed into Inuit Today.

Figure 1

Alootook Ipellie at work

Photograph published in 1981 in Inuit Today 9 (6): 7

This bi-monthly publication aimed to bring forward a unified voice to Inuit communities. Inuit Today also disseminated stories about people’s experiences; an essential task, as different generations of Inuit found themselves culturally alienated, notably due to the settler-colonial project of assimilation propelled through the system of Canadian Indian Residential Schools (Murray 2017, 748).

Ipellie gradually began doing illustrations for Inuit Today and later became its editor. Throughout his career, he produced an extensive number of poems, essays, articles, political cartoons, and drawings, as well as serial comic strips (including Ice Box and NunaandVut). Although he spent his adult life living in Ottawa, Ipellie was dedicated to the social, political, and cultural changes and issues occurring in Inuit Nunangat (Dyck, Igloliorte, and Lalonde 2018). He attempted “to focus on the problems of the world and the reality of events that [were] happening in the Arctic” (Ipellie 1996, 161). Indeed, several publications of Inuit Today between the 1970s and 1980s provide a rich cross-section of the some of the important political events that occurred in Inuit Nunangat and notably the excitement rising over the imminent creation of the territory of Nunavut in the 1990s.

Although Ipellie sold some of his artwork or gave them to friends and family (Amagoalik 2008, 40), his art only came to be recognized later in his career. The Canadian Eskimo Arts Council—which he called “the government-appointed stewards of Inuit art”—was disinterested by his work which, in its view, did not correspond to so-called endorsed Inuit art (Ipellie 1993). Using pen and ink with imaginative prose fiction, his style was considered darker than was “mainstream” Inuit art. Ipellie’s art therefore challenged North Orientalism because it did not ascribe to the typical style of Inuit graphic arts that Qallunaat were looking for and it refused to answer to such expectations.

One of Ipellie’s critiques of how the Arctic gets construed is demonstrated in his 1975 poem The Trip North (Inuit Today 4 (3) 1975: 75). Addressed to Qallunaat, this poem describes the act of imagining the North and travelling in the Arctic to “find the very truth of it.” Ipellie ends with “You now read about the Arctic/ In the comfort of your chair…” to remind Qallunaat that despite their curiosity and appreciation of the North, they only really get to “experience it” as a relatively short holiday trip, filled with beauty and extreme experiences, but not as their home or as part of their everyday life. Ipellie’s words also suggest that settlers get to think about the Arctic at a comfortable distance from it, thus criticizing how Qallunaat imagine, know, and construe “the North.”

No living generations of Arctic narrator will ever get enough satisfaction out of spinning yarns about the Arctic and its cast of thousands from the bygone days of this very moment.

I am standing here in front of you to announce, unfortunately, that none of us will ever live long enough to finally complete the elusive final book on the Arctic and its people… The Great White Arctic will remain an unfinished story to the very end of human habitation on planet Earth. How sad.

Ipellie 1995, 96

Through their attempts at “knowing the Arctic,” settlers tend to confirm stories they already know, or at least they think they know. As suggested by geographer Emilie Cameron (2016, 14), “[Qallunaat] need to learn not only the shape of [their] influence and claims and inheritances but also the limits of those claims and all the ways in which [they] do not matter and do not know.” Cameron adds that we must neutralize what enables “[Qallunaat] to pretend that [their] witnessing is benevolent, objective, and appropriate.” In contrast, Ipellie’s drawings and written works oppose how the colonial gaze consumes images of the Arctic. In that respect, he believed that his career as an artist and a writer was a way to speak “to both sides at the same time” (Ipellie 1996, 161).

A recurring theme that can be observed in Ipellie’s artwork is the expressed tensions between boundaries, geographies, worldviews, and ways of being in the world. His graphic style is characterized by bold, sharp, and precise black ink lines on white paper. This essay proposes a series of reflections on the Arctic representations through the symbolic thickness of Ipellie’s graphic lines. I suggest that through his lines, Ipellie defied categories, boundaries, and reductive dichotomies. Rather than splitting the world into two sharp pieces, he dwelled in the boundary’s spatial and temporal thickness—the in-between—which was so characteristic of his cultural upbringing and the tensions experienced in Inuit Nunangat.

The following analysis thus proposes a reading of the manifold representations of the dwelling in Ipellie’s work. Developed in three parts, I begin by addressing land representations that notably portray the richness of the territory rather than space as a container for settler infrastructure. Drawings that explore the central themes of land disputes and the exploitation of the environment are also examined. I then delve into Ipellie’s representation of buildings, as he witnessed the pre-colonial to the colonial and welfare state transition. This artist’s humour-based approach constituted a strong social and political critique of existing housing issues and settler-colonial building practices, and he acknowledged his ancestors’ wisdom when speaking of traditional housing, thus advocating for the intricacies of Inuit concepts of dwelling. I also discuss how Ipellie’s work included representations of multiple voices in the struggles over space, whether Inuit communities or non-human ones, including animals and land.

Finally, I focus on Ipellie Alootook’s work in Inuit Today as a critical cross-section through key moments in Nunavut history from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, and particularly Ipellie’s readings of space. It is not an attempt to theorize Inuit space but rather a contemplation of how these representations challenged ways of knowing in Arctic communities. Dwelling on the notion of lines and the in-between—the interstitial space, a space of ambiguity—I reside on what cannot be known or reconciled, in an attempt to embrace an “ethics of incommensurability” (Tuck and Yang 2012, 28) to inhabit the gap between cultures and spaces through Ipellie’s lines. I suggest that the artist created a suspended space between settler assertation of sovereignty and the vitality of an Indigenous territorial jurisdiction that is worthy of consideration.

Metaphorical entanglements of the lines abound in the central themes of his graphic art, notably those referring to settler-colonialism, boundaries, frontiers, roads, pipelines, spatial construction, buildings, and planning. In his poem Walking on Both Sides of an Invisible Border, expressing the struggle of “walking on an invisible border”, Ipellie writes, “I am left to fend for myself walking in two different worlds trying my best to make sense of two opposing cultures” (Ipellie 1996, 155). Under these ambiguous, layered, and tense conditions, Ipellie’s work gains to be better understood and this artist acknowledged as a prominent figure and voice to issues pertaining to Inuit Nunangat.

Representations of the Land

An old man dies with stories worth thousands of pages in his memory. No one ever gets to know just how much valuable information he had: information which we, as young Inuit, could have learned a great deal from, as could the outside world. The old people who are still living maybe have a few words to say concerning their views. And if they have a story to tell, there is bound to be something in their story that will shine through like the light of a candle in a darkened room.

Ipellie 1975a, 56

Inhabiting Paper and Stories

Ipellie’s beginnings with the metaphor of the in-between started with his graphic work in Inuit Today. As mentioned in the introduction, Ipellie first worked for the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami as a typist and translator. He introduced fillers in the publication—to be placed between or at the end of articles—anywhere where text did not harmoniously cover a page. In an interview with Michael Kennedy (1996, 158–9), Ipellie explains:

I started to do these fillers because they needed to cover space in the magazine. I did these very small little characters with no captions whatsoever, just images of everyday life. […] I realized there was a need for my work. I helped to fill each magazine issue with what was happening with my people, what needed to be said about current events. It was to fill a void that needed to be filled.

In these gaps, Ipellie presented simple, yet rich drawings of the land, sometimes depicting scenes of quotidian life, such as hunting, travelling, fly-fishing, animal crossings, kayaking, gatherings, and so forth (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Selected “fillers” drawn by Alootook Ipellie in various issues of Inuit Today between 1974 and 1982.

Postcolonial theorist Bhabha shed light on the concept of the supplementary to describe how postcolonial space is considered subaltern to the metropolitan centre: “The liminality of the Western nation is the shadow of its own finitude: the colonial space played out in the imaginative geography of the metropolitan space” (Bhabha 1990). Indeed, as opposed to the density of Southern cities, the Arctic is often imagined as startlingly bare, arid, and empty. Settlers operated through the assumption of terra nullius, despite the occupation of territory by Inuit peoples, developing complex narratives to reconcile the colonial imaginary of bare land and the embodied experience of settlement. The limited territorial literacy of colonists thus allowed for dehumanized representations of the Arctic, rendering it a sterile space.

In Ipellie’s drawings, the land is represented not as bare but rather with textures, topographies, animals, snow, wind, snow houses, humans, and dwellings. The fillers were therefore not solely a representation of the land but rather a poetic involvement in it. The juxtaposition of the artist’s vignettes representing land and Arctic life alongside stories and articles about Inuit Nunangat evokes a site where land and history do not figure as mutually exclusive alternatives. Ingold writes that for Indigenous people, “[b]oth the land and the living beings who inhabit it are caught up in the same, ongoing historical process” (2011, 139). The juxtaposition of text and image displays the entanglements of space, where the landscape abounds with life… and stories.

Mocking the Lines of Property

In February 1973, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada organization (now known as Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami) proposed to the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs to research Inuit land use and occupancy in the Northwest Territories of Canada. The resulting report, the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project (ILUOP), was released in 1977 and subsequently triggered negotiations that culminated in the 1993 Nunavut Agreement’s land rights provisions. In January 1974, Ipellie published in Inuit Today the first installment of his Ice Box cartoon series and examined issues affecting Inuit in what was still a time of severe social transition. The Ice Box characters, the (fictional) Nook family—Nanook, Bones, Mama Nook and Papa Nook—are shown playing and working together despite government interference and cultural instability. The family is constantly interacting with the land, the weather, and the Ice Box community (Grace 2007, 249), and the storylines sometimes play out or subvert with stereotypes that Qallunaat have about Northerners; for example, with Inuit characters always smiling. The stories are generally full of surprises and the humour is sometimes accompanied by a comment on a particular social or political event.

In Figure 3, we see the Nook family participating in what appears to be a particularly long tug of war. Because the comic strip is printed on four different pages, the readers’ expectations are suspended, as we wonder about what is being pulled. Each character employs different strategies and strengths in their endeavour; for example, Mama Nook and Bones use gravity and rocks as pieces of the land to increase their efforts. Upon turning the page, we discover the two last boxes displaying (with satire and criticism) the forces against which the Nook family is fighting.

Figure 3

The Nook family and the government in a rope-pulling game

The comic strip, published in 1981, simultaneously announced the 1982 plebiscite for the creation of Nunavut, where voters were asked, “Do you think the Northwest Territories should be divided?” Indeed, the illustration represents and mocks colonial forces and government agents. The latter are portrayed as jaded businessmen with individualistic interests, such as their houses in Southern Canada. The Qallunaat character on the right, holding the end of the rope, expresses his love for assimilation. Between the Nook family and the Southerners is a crank oscillating between Nunavut and Northwest Territories. In this sarcastic tug of war game, representing the political debate of the time, Ipellie intentionally criticizes the government and industries that exploit the Arctic, including census-takers, environmentalists, educators, and entrepreneurs who treat Arctic communities as marginal colonies with no distinct identity or value (Grace 2007, 250–1.) The rope’s precarity echoes the abstracted lines representing the boundaries in maps, ultimately challenging how land gets divided into territories and is conceptualized as property. Coincidentally, the 1977 Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project (ILUOP) played a defining role in expressing the cultural and ecological circumstances of Inuit society and provided an explicit statement of Inuit perceptions of the man-land relationship (Freeman 1976, 19). In this instance, it could be argued that in Ipellie’s 1981 comic strip, the thin line pulled in opposite directions parodies the struggle over territorial definition and boundary making.

As in many of Ipellie’s comics, the dualistic tension and the snub to settler worldviews is made manifest in that it is written simultaneously in English and Inuktitut, thus embracing the two cultural conditions in which Ipellie found himself. The presence of Inuktitut syllabics is a direct reminder to Qallunaat that they cannot fully understand the situation. Although Ipellie’s drawings were for both cultures, he denounced their asymmetrical relationship and interests. In his editorial work in Inuit Today, Ipellie fulfilled a personal goal “as an interpreter of Inuit concerns to bring about dialogue between Inuit, the government, and mainstream society in the South” (Ipellie, 1993). He also wrote that he was “well aware of [his] place in the Inuit community” in that he sought to project a recognizable face as well as a united voice to Inuit’s struggles (Ipellie, 1995, 101).

Ipellie wrote an article entitled NWT Separates from Canada, initially published in 1977 in Inuit Today and later reprinted in Paper Stays Put: A Collection of Inuit Writing (Gedalof 1980). In this satire, he imagines that the Northwest Territories want to separate from Canada and therefore announce a referendum (Figure 4). Inspired by the Québec Separatist movement, Ipellie speculates on the reactions from different peoples. For example, he portrays Pete, a (fictional) patriotic bartender in Inuvik who can’t imagine living in a separate state from the rest of Canada:

Canada is my homeland, and I aim to remain a devoted Canadian as long as I stand on this Earth! I look upon Canada as a saviour of human dignity and a symbol of freedom for mankind. It is sad that the Inuit nay choose to leave it! Look, the government of Canada has done a ton of good for these poor creatures of the North! It has developed the North in a proper manner, in a humane way, and in the right way!.

Ibid., 37

In the liberalizing fiction of development, Canada’s figures as “peacemaker” and “good colonizer” are used sarcastically as a critique of the contradiction in Canada’s reputation. Ipellie’s mockery of settlers then extends to Southern political leaders: “Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Minister Buddy Boss could not be reached for his reaction. He was rumored to be in his little hideout somewhere in the Gatineau Hills across the Ottawa River from the Parliament Buildings” (Ibid., 39).

Here, Ipellie denounced that decision-makers did not live in Indigenous communities but detained privileged positions in the Canadian government with which they were more closely connected.

Figure 4

Satirical drawing of the Northwest Territory (and Yukon) separating from Canada. The anthropomorphized map is literally walking away from Canada

Published in Inuit Today 4 (9), 1975: 50

Ipellie also imagined the reaction of Inuit youth to the separation of the Northwest Territories:

It has been the general feeling among the young people of the North that it is about time the Inuit were given a fighting chance to run their own affairs. He said the young people have a lot at stake in this referendum and must not be counted out in any way. [The president of the student council at the Gordon Robertson Education Centre in Frobisher Bay] called for a vote for every student in the North regardless of their age because he said their very future will be decided upon in this referendum.

Ibid., 38

In advocating for political self-determination, Ipellie raised a critical point in suggesting that youth should be allowed to vote for decisions that concern their future. He also speculated on the opinions and reactions of different communities and stakeholders, such as former prime minister Pierre-Elliot Trudeau, the Student council, ministers, commissioners, the Northwest Territories council, and so forth, thus bringing forward different perspectives. Through the complexity of humour and critique, Ipellie’s imagination blurred the boundaries between dualistic conditions by bringing forward the complexities of opposing interests.

Lines Against Extraction

“I’ve never lost that connection to the land,” said Ipellie in his interview with Michael Kennedy (1996). Despite living in Ottawa, Ipellie continuously visited Iqaluit, torn between geographies and worldviews. His outlook on his own culture and the invading Qallunaat culture prevailed as an important theme in his work. Just like his ancestors relied on the land, land was, for Ipellie, an inspiration. According to him, his art espoused techniques of observing, listening, and practicing what he learned from Elders (Ipellie 1995, 98).

they were settled

treating the land as their most prized

possession

they did not know how to abuse it

for it was this land that gave them

their life

the same land they shared with

the animalsthey hunted together from their new camp

getting used to the surrounding

land and seathey felt was if they were tourists

each character of the terrain

Excerpt from the poem The Strangers (Inuit Today 7 (1), 1979: 19–24)

was recorded in their minds

each island and river was given

their undivided attention

In his 1979 poem The Strangers, Ipellie begins by celebrating Inuit’s traditional knowledge of and profound respect for the land, the animals, and the sea. The poem continues with the encounter between Inuit peoples and Qallunaat, retelling the history of trade relations, invasion, religious conversion, and settler laws and education. He writes, “wooden igloos were built/ mind you they never bothered/ to ask for permission to do/ what they were doing” (1979, 21).

Some of Ipellie’s drawings also radically opposed the extractive industries encroaching upon Inuit Nunangat in the 1970s. During that time, projects such as the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline in the Northwest Territories and the James Bay Project in Northern Québec spurred much discussion among Inuit. In his 1981 drawing (Figure 5), Ipellie juxtaposes a scene of an Inuk coming home after seal hunting while miners are digging a trench around the snow house. In the illustration, the spatial constriction of the dwelling parallels that of the settler-colonial settlements in the Arctic, which have not only forced Inuit into permanent settlements but have even prohibited forms of mobility, notably through the mass extermination of dogs in the Eastern Arctic between 1950 and 1975 (Qikiqtani Truth Commission 2013). Only a wooden board spans over the trench to access the dwelling. The board appears long, suggesting a spatial distance or precarious access to land for hunting.

Figure 5

Satirical cartoon criticizing the extractive industries

Published in Inuit Today 9 (7), 1981: 12

In this scene, none of the miners seem to notice the hunter. One of them is examining a mineral through a magnifying lens while the other displays an expression of content, suggesting a collaboration between the scientist and the industry, united in the capitalist exploitation of the land. The other miners are concentrated on their task of digging, leaving residues of their destructive activities on the ground. The natural gas line merges with the landscape’s horizon line to the left, recalling the large scale of such infrastructures and their benefit for Southern communities. On the upper left, two Inuit overlook the scene at a distance. One of the characters utters to the reader (in English only): “Now will you believe me that our people’s human rights are a bit on the wee side?” The character thus confronts the viewer in a triad where the witness’s gaze is complicit with the scene.

Ipellie viewed his role as that of defender of the interests of the Arctic communities and the environment. In 1995, emphasizing his activism, he wrote:

We [writers and/or artists] sometimes have to play the part of “Alarm Bells” in order to help humanity wake up from its ugly lethargy in a lifetime that cannot end too soon. I speak of the prevalence of endless human poverty, the human slaughterhouse of useless wars, and the mindless abuse of our and only lifeline, the planet Earth; not to mention the slow deterioration of the fragile Arctic ecosystem, which all of us should help preserve, whatever way we can.

Ipellie 1995, 100

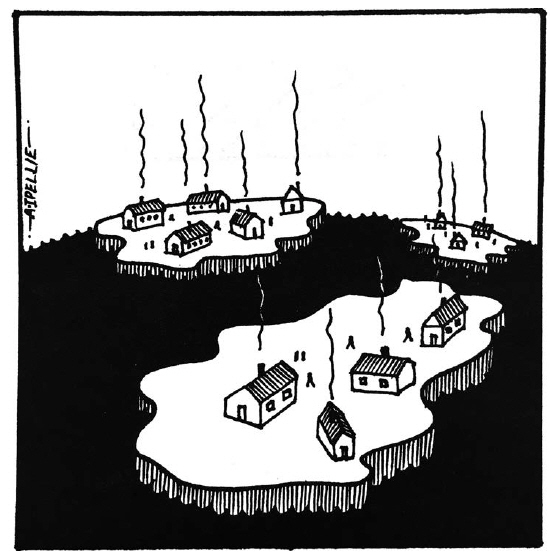

Ipellie’s concerns for the environment were not limited to Canada or the Arctic. In one of his illustrations (Figure 6), he takes an alarming stand by depicting the consequences of the climate crisis. Of interest is that he drew the dwellings not as snow houses, as he often did, but as “Qallunaat houses”—thus suggesting the effects of Qallunaat influences on the environment. The drawing also reveals a curvilinear horizon line, thereby prompting that the issue also occurs on a planetary scale. It remains unclear as to whether the ice is melting or the water level is rising. Nevertheless, Ipellie blurred the geographical and cultural boundaries of his activism.

Figure 6

Illustration of the climate crisis

Published in Inuit Today 4 (5), 1975: 83

Representations of Dwelling

That piece of land

Was there as free

And open as the

Great sky above.

It was there for

Us to play on.

It was there for

Everyone to use.

But now, in the midst

Of change in time,

A concrete building

Has been built.

A wire fence has

Been put up so we

May not touch it unless

We are given permission

By the authorities

Who built this concrete

Rock that give us

No joy when it meets

These eyes of ours.The one who built this

Excerpt from the poem A Piece of Land (Inuit Today 4 (3), 1975: 73)

Concrete rock never

Asked our people if it

Was OK for them to have it.

Translations—From Colonial to Welfare Space

The 1960s in the Canadian Eastern Arctic saw the emergence of government programs which, termed under the guise of ‘welfare’, included education, health care, and eventually housing. The Eskimo Rental Housing Program launched in 1965 aimed to encourage people to leave behind their semi-nomadic lifestyle and settle into hamlets (Dawson 2008). Amid the transition from a nomadic to a colonial welfare state, some of Ipellie’s drawings explore major political, social, and cultural issues. In the Ice Box comics, the illustrations often comprised a complex mixture of the two cultures—Qallunaat or Euro-Canadian and Inuit. As pointed out by Ipellie himself (Kennedy 1996, 159), while the cartoons illustrate a setting in the Arctic, the storyline is often from the South.

In his examination of the relationship between narratives and nation, Bhabha considered the act of representing one’s culture while being exiled from that culture, thus becoming an interpreter or intercultural translator. According to Bhabha, this act of translation resumes into an act of imagining a community that never inhabits a horizontal, homogenous space. Envisioning a community requires a metaphoric movement that enfolds “a kind of ‘doubleness’ in writing; a temporality of representation that moves between cultural formations and social processes without a centred causal logic” (Bhabha 1990, 293). The author adds that it is necessary to embrace ambivalence to attend to the intersections of time and space that constitute the modern experience of culture and nation. Figure 7 shows an example of this ambivalence in the different types of dwellings drawn by Ipellie: a snow house and what could be governmental housing. The non-linearity of the temporal and spatial boundaries of Ipellie’s drawing thus attended to, yet did not reconcile the complexities and ambivalences of the Arctic in relation to Southern metropolises.

Figure 7

Juxtaposition of snow houses and government housing

Published in Inuit Today 4 (6), 1974: 69

In Canada and the Idea of North, author Sherill Grace comments on the bilingualism of Ice Box by noting that, “as with the visual space, the verbal semiotics construct an economy of plenitude and social presence” (2007, 250). This verbal semiotic attends to the gap between cultures and the in-between, which strongly characterizes Ipellie’s experience. In her book, Life Among the Qallunaat (2015), Inuk author and translator Mini Aodla Freeman (2015) writes about the notion of in-between in multiple instances, using the term “being in the middle” to describe how she liked studying people around her, whether she was in the South or the North. Her chapter entitled I am in the middle describes her work as a translator travelling to Frobisher Bay, Baffin Island, and the Northwest Territories and the challenges of connecting with her Qallunaat colleagues as well as with Inuit she encountered (Ibid., 135–136). She also writes about being “caught between two lives” (ibid., 94) when describing her return to her community in James Bay. She compared her situation to that of an Inuk man who “was caught between his desire to go hunting and the clock, which was at one time never important to him” (ibid., 136). This notion of in-between along with questions of literal and metaphorical translation of Inuit and Qallunaat cultures are predominant themes in the work of both Mini Aodla Freeman and Alootook Ipellie.

Satire as Survivance Space

Colonization of the Arctic meant that people also became estranged from their humour (Prouty 2018, 30). At that time, the literature, photography, and films produced by Qallunaat tended to portray Inuit either as stoic hunters or as childlike, naïve, and desexualized primitives reliant on Qallunaat. Ipellie used satire and witty humour to counter these stereotypical representations and communicate important issues pertaining to Inuit Nunangat. He wrote, “[y]ou and I know that we will never tire of being entertained by social satirists, who are amongst the best interpreters of this world-wide tragicomedy” (Ipellie 1995, 96). Indeed, Ipellie’s work, like laughter medicine, often parodies how Qallunaat view the Inuit and the Arctic. His drawings make fun of how settler cities were constituted and normalized. For example, when the internationally renowned architect Moshe Safdie visited Pond Inlet and asked what the people wished to see built, some people answered, “[t]he houses here have no colour, and the few that do are very dull. We want them painted like Bryan Pearson’s store in Frobisher Bay […]. For those of you who haven’t seen the store, it is painted in bright reds, greens, blues, yellows and oranges in stripes all around the building.” (Inuit Today 4 (3), 1975, 68.) One could imagine how amused Ipellie was by the idea of Pond Inlet’s houses covered in stripes (Figure 8), thus making for a very colourful and photogenic cityscape ideal for postcards.

Figure 8

Postcard of buildings painted in stripes in Pond Inlet

Published in Inuit Today 4 (3), 1975: 68

In a world that commodified Inuit art while devaluing and oppressing Inuit cultures (Igloliorte 2020), Ipellie resisted through humour and playfulness. He challenged Qallunaat expectations about Inuit art by creating unidealized images of the Arctic (Prouty 2018). In Inuit culture, what is interpreted as the closest to satire is found in the word unipkaaqtuat. This term translates approximately as “myth” or “legend” but does not have an exact English equivalent (Ibid., 2018). In her essay entitled Conflict Management in a Modern Inuit Community, anthropologist and linguist Jean Briggs (2000, 111) describes Inuit humour as exaggerated or playful jokes that are allowed for indirect requests, personal wishes or complaints. For example, when community members notice improper behaviour, they address it with jokes. When there are tensions, satirical song duels take place to air grievances, thus avoiding violence. Prouty (2018, 35) asserts that Ipellie’s subversive humour can be considered as a “powerful decolonial strategy” that maintains traditional strategies to avoid confrontation but corrects improper behaviour according to Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit.

To echo the concept of humour as a decolonial strategy, Inuk scholar, curator, and art historian Heather Igloliorte writes about the concept of “resilience.” She argues that “resilience is a reaction to oppression that is significantly different from resistance: It draws from Inuit values that favour the communal over the individual and is cultivated through the adoption of mature defences—such as humour and altruism” (Igloliorte 2010, 44–5). In other words, Ipellie’s satirical art relied upon Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit while using entertainment to denounce serious issues brought on by settler-colonialism in the Arctic.

That Ipellie’s work contrasted serious subjects with humour reverberates with what Anishinaabe writer and scholar Vizenor describes as the concept of “survivance,” namely, a practice of retelling Indigenous stories through any medium to assert Indigenous presence in the present. He writes: “[t]he discourses on literary and historical studies of survivance is a theory of irony. The incongruity of survivance as a practice of natural reason and as a discourse on literary studies anticipates a rhetorical or wry contrast of meaning” (Vizenor 2008, 11–12).

Vizenor’s theory of irony therefore suggests practices that counter the unbearable stories of dominance, tragedy, and victimry. Similarly, Ipellie’s work embraced contrasting affects by combining humour and a critique of colonial violence—portraying both tradition and novelty (Figure 9)—and his use of satire can be read as either decolonial, resilient, or survivance practices.

Figure 9

Cambridge Bay’s hotel illustrated as a multiple story snow house

Published in Inuit Today 5 (2), 1976, 49

“Writing Back” Space

Ipellie’s satirical work often offers a “double fight”: one against the source of the parody and one against those who misread the text. Indeed, his satirical drawings are often voluntarily ambiguous, thus offering multiple possible interpretations. Grace (2007, 250) refers to this double fight strategy as writing back. In Ashcroft Griffiths, and Tiffin (2002, 39–9; 114–5) the authors note that “writing back” not only resists appropriation or co-option by the dominant group but also “asserts its own construction of identity and reality.” It is thus essential that Ipellie’s drawings be appreciated not only as light-hearted, satirical, and whimsical artwork but also as an effort to maintain awareness of the cultural oppression experienced by Inuit peoples.

Figure 10

Ipellie advocating for a health center in Kewatin, Nunavut

Published in Inuit Today 6 (6), 1977: 81

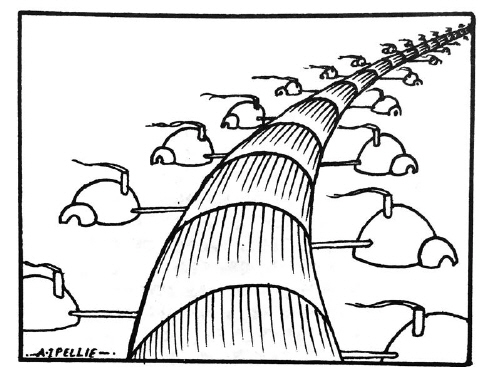

Ipellie’s drawings and writings in Inuit Today coalesced activism, reporting, critique, parody, and storytelling. Frequently commenting on Southern spatial codes and practices of power, Ipellie noted, for example, that “Qallunaat couldn’t do anything small-scale…. endless roads, endless high-rises and houses, endless human beings” (Ipellie 2001, 28). When portraying buildings, Ipellie fused typologies, shapes, arrangements and codes. His creations were indeed a form of writing back, as is evidenced in his drawing of housing connected to an oversized and infinitely long pipeline structure (Figure 11).

Figure 11

Houses disposed along and connected to an endless pipeline

Published in Inuit Today 4 (1), 1975: 47

Remembering Space

Ipellie also wrote a series of stories in Inuit Today called Those Were the Days, depicting Inuit ways of life on the land. He saw himself as an “Arctic Narrator—mad, nomadic, locomotor, gone wild, living in a society that tries so hard to appear, feel, taste, sound and smell ‘civilized’” (Ipellie 1995, 101). For him, storytelling and writing were a form of medicine, “a way of coming to terms with the demons of [his] past. They were [his] real therapist” (ibid., 99). Some of Ipellie’s stories, inspired by his grandfather’s narratives (Kennedy 1996)—memories of daily life—pointed out significant changes in Inuit society and brought to light the many divergences between Qallunaat and Inuit worldviews.

Ipellie thus used drawings and stories to remember, to bring his memories into a tangible world. In the following excerpt, he recalls when he moved from a semi-nomadic lifestyle to the settlement of Frobisher Bay and government-built houses:

My earliest memories of Iqaluit have to do with living in a hut in the wintertime and then moving into a tent from the start of spring until early fall. Most of the Inuit families who had moved to the community did the same. We simply could not stand living in a dark hut when we could enjoy so much light inside the white canvas tents. These seasonal rituals slowly died when the government began building pre-fabricated houses for all Inuit families. So each year, the numbers of the Inuit-built huts dwindled, until one day the last one was torn down. We were well on our way to living in a semi-modern world as set out by government workers and administrators. It was during the same time that we were slowly forgetting and abandoning our distinct way of doing things and looking at the world. On the other hand, unbeknownst to many of us, it was being taken away from us. Our world would never be the same as it had been.

Ipellie 2001, 27

Ipellie’s vivid memories of the transition of dwelling reference the cultural alienation that took place during the 1960s, which saw the emergence of government programs, termed under the umbrella of ‘welfare’ and including education, health care and housing, with the goal of getting people to relinquish their semi-nomadic lifestyle and settle into hamlets.

Another example of storying memory was when Ipellie collaborated in the early 1970s with filmmaker Co Hoedeman to fabricate the set design for a National Film Board short movie (Ipellie 1976, 53–7). He was asked to fabricate a snow house (made of Styrofoam) for the animated characters. The movie The Owl and the Raven: An Eskimo Legend tells the story of how the raven acquired its black feathers. As the film unfolds, figurines of bones representing characters and the plan of a snow house are reproduced through the raven’s and the owl’s play. This mise en abyme of a story within a story, a snow house within a snow house, shows the complexity of narratives in Inuit traditions.

Ipellie’s stories and drawings are similar in structure in that they consistently contain multiple stories and angles, defying temporal frameworks. In Figure 12, we see Nanook building a snow house and praising Inuit inventiveness and technologies. As he himself is building and re-enacting building traditions, he invents a new building shape. Here, Ipellie is perhaps suggesting that Nanook innovates without disavowing the past, as did his ancestors. Conceivably, he could be arguing that in order to narrate the past, one must invent. Both the Ice Box comic and the short film allude to ways of construing stories and highlight the false distinction between past and future temporalities.

Figure 12

Nanook building a snow house. Ice Box

Published in Inuit Today 4 (1), 1975: 4–5

Representations of Multiple Voices

Let us write passages that will sway the centuries-old impressions that others have about our true colours. Let us put, without a moment’s hesitation, a voice in the mouth of our silent mind. (Ipellie 1995, 96)

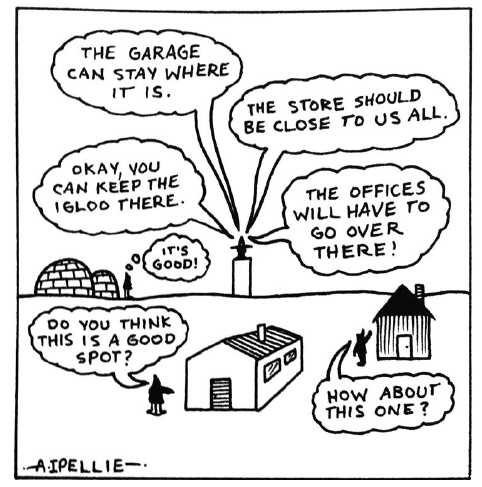

Amplifying Inuit Voices

The creation in 1975 of the Inuit Non-Profit Housing Corporation (INPHC)—also governed by the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami—aimed to address housing issues in the Northwest Territories. Following the creation of the INPHC, Inuit Today sought the people’s opinion on the conditions of their houses: “Inuit Today would like to know how you feel about the quality of your house. What are the problems with it? How would you like to see it changed?” (Inuit Today 5 (5), 1976: 63).

Indeed, Inuit Today regularly reported on the state of housing in different parts of the Arctic and gave voice to local concerns regarding this issue. In Figure 13, many characters are represented discussing the location of buildings. At the center, on top of a distant tower, a character is illustrated giving directions to the other people for the site of a garage, a store, and offices. It is unclear whether the drawing refers to an architect or a planner, but it does comment on the spatial planning of Northern communities.

Figure 13

A conversation between community members and a character on a tower regarding the placement of buildings.

Published in Inuit Today 7 (1), 1979: 48

Ipellie’s way of contributing to housing activism happened through his engagement with his readers—storytelling, listening, commenting, writing, reporting, criticizing, questioning, and illustrating; in other words, to make sense of this “colonial cacophony” (Byrd 2011). Inuit Today would sometimes openly oppose projects, such as the controversy around the staff-only development project by Montréal-based architect Moshie Safdie. Joining the voice of the Frobisher Bay Housing Association, the newspaper adamantly denounced the segregation and double standard of housing: “Frobisher Bay has been and still is a segregated village containing double standards of accommodation: the government employees in the high-quality homes, the local Inuit in the low” (Ipellie 1975b, 22).

Figure 14

Nanook gets a new jacket for the winter, but it doesn’t fit. Ice Box

Published in Inuit Today 3 (9), 1974: 2–3

In addition to writing on political, social and cultural issues, Ipellie aimed to help Nunavummiut express their views and opinions about political decisions made on their behalf. For example (Figure 14), Nook is offered a new jacket which should keep him warm in the upcoming winter. However, the garment proves not to be adapted to Nanook. His family tries unsuccessfully to help him and even suggests that he is the problem because his head is too large. In the end, Nanook is left alone, stuck in a delicate position, as his family leaves to hold a meeting without inviting him—and worse—on his behalf. Here, the cartoon and the unsuitable jacket parallel the way inappropriate housing was designed in Southern Canada on behalf of Northern communities and is an intentional metaphor for the lack of communication and consultation regarding proper dwellings.

Multiple Voices

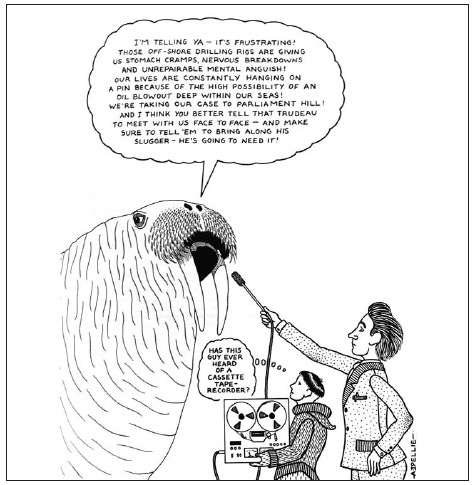

Ipellie’s interpretation of multiple voices ventured beyond the boundaries of Northerners and Southerners, Inuit and Qallunaat. In several instances, Ipellie drew talking animals, often responding to journalists (Figure 15) or interacting with other characters. In one edition of Ice Box, Nanook speaks to Mother Nature and she responds (Inuit Today 7 (4), 1978: 2–3), suggesting that the land is sentient. Once again, the colonial assumption of land as a neutral container for settler structures is challenged.

As suggested by feminist scholar Donna Haraway (2016, 116), “We are all responsible to and for shaping conditions for multispecies flourishing in the face of horrible histories […]. The differences matter—in ecologies, economies, species, lives.” She proposes a framework for thinking about the multiple forms that kinships can take in a multispecies world. Ipellie embraced a similar form of “response-ability” by drawing the animals’ agency over political matters in ways that did not only center on human concerns. Ingold (2011, 139) also challenges human exceptionalism by suggesting a shift from a conversation about biocultural diversity to a field of dwelling for beings of all kinds, human and non-human. Ipellie’s discursive landscape is therefore multiple, entangled, and complex and calls for the shattering of hierarchies between species.

Bold Lines—Dwelling on the Border

As discussed by Aurélie Maire (2015, 439), Inuit graphic artists have played a significant role in political activism and the critique of the settler-colonial state. For example, the work of Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona denounces environmental issues, namely, the impact of waste disposal in Inuit communities, while the art of Annie Pootoogook—particularly her attention to details and mundane scenes—often reads like short stories (New Museum 2010, 178) and denounces social issues regarding Inuit Nunangat. Ipellie, Ashoona, and Pottogook thus challenge Qallunaat expectations of Inuit art and de-exoticize the Arctic (Igloliorte 2020). Alootook Ipellie thus remains a key Inuit intellectual figure, and his work reflects crucial moments of the intense process of political mobilization and Inuit self-representation taking place between the 1970s and the 1990s.

Figure 15

walrus commenting on oil extraction and Canadian politics

Inuk scholar, historian, and curator Heather Igloliorte notes a “shift in the Inuit independence and return to self-determined existence brought about by the practice of [Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit], paralleled with the growing critique of past representations and an assertion of Inuit self-representation […] offering at once a critique of colonial representation and its antidote” (Igloliorte 2017, 111). In this perspective, in layering the critique of colonial practices and addressing anti-colonial Inuit representation, Ipellie’s work has been vital in challenging land representations, bringing forward Inuit and non-human voices, creating awareness of land exploitation and housing issues, and celebrating traditional Inuit knowledge.

Geographer Emilie Cameron argues that Inuit resistances, re-narrations or responses to colonial discourses also “reproduces colonial relations in that Inuit are called upon to respond to [Qallunaat] in modes, formats, and terms that are dictated by, and legible to [Qallunaat]” (Cameron 2016, 15). While Ipellie described himself as an interpreter of Inuit concerns (Ipellie 1993) in both the government’s and Southerners’ eyes, he also challenged Qallunaat expectations of Inuit representations.

Ipellie’s bilingual drawings and writings thus embrace the in-between with an ambiguity and multiplicity of meanings and readings. This ambiguous space is a reminder that his work is not, and should not be fully understood by Qallunaat. As a settler of European ancestry whose first language is not Inuktitut, my cultural experience and linguistic background cannot “know” and interpret the richness of his work. In that regard, Ipellie’s graphic art and bilingual publications provoke us to question our interpretations of and position within colonial relations.

Through his representations of land, buildings, and human and non-human voices, Ipellie actively construed and questioned contemporary Nunavut. Using writing and drawing, he occupied the spatial and temporal thickness of lines, thus shattering the dualistic concepts and boundaries of space and cultures and criticizing the lines of settler-colonialism, boundaries, frontiers, roads, pipelines, spatial construction, buildings, and planning. Ipellie’s poem Walking on Both Sides of an Invisible Border (1996) best illustrates this condition of this border on which he must perform “a fancy dance.” He writes, “I have resorted to fancy dancing/ In order to survive each day […] Sometimes this border becomes so wide/That I am unable to take another step”. Ipellie thus explored the thickness and incommensurability of the border upon which he dwelled.

Appendices

References

- Amagoalik, John, 2008 “Alootook Ipellie.” Inuktitut, 104: 40–45.

- Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, 2002 The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Postcolonial Literatures. London and New York, Routledge.

- Bhabha, Homi K., 1990 “DissemiNation: Time, Narrative, and the Margins of the Modern Nation.” In In Nation and Narration, edited by Homi K. Bhabha, 291–322. London and New York, Routledge.

- Briggs, Jean, 2000 “Conflict Management in a Modern Inuit Community.” In Hunters and Gatherers in the Modern World: Conflict, Resistance, and Self-Determination, edited by Peter Schweitzer, Megan Biesele, and Robert K. Hitchcock, 110–124. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Byrd, Jodi A., 2011 The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. First Peoples: New Directions Indigenous. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

- Cameron, Emilie, 2016 Far off Metal River: Inuit Lands, Settler Stories, and the Making of the Contemporary Arctic. Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press.

- Dawson, Peter, 2008 “Unfriendly Architecture: Using Observations of Inuit Spatial Behaviour to Design Culturally Sustaining Houses in Arctic Canada.” Housing Studies 23 (1): 111–128.

- Dyck Sandra, Igloliorte Heather, and Lalonde Christine, 2018 “Alootook Ipellie: Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border.” Exhibition curated by Sandra Dyck, Heather Igloliorte, and Christine Lalonde. Presented at the Carleton University Art Gallery from September 17th to December 9th, 2018.

- Freeman, Milton M. R., ed., 1976 Land Use and Occupancy, Vol. 1 of Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project Report. Ottawa, Supply and Services Canada.

- Freeman, Mini Aodla, 2015 Life Among the Qallunaat. Winnipeg, University of Manitoba Press.

- Gedalof, Robin, and Alootook Ipellie, 1980 Paper Stays Put: A Collection of Inuit Writing. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers.

- Grace, Sherrill E., 2007 Canada and the Idea of North. Montréal, McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne, 2016 Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, Duke University Press.

- Hoedeman, Co, 1973 The Owl and the Raven: An Eskimo Legend. National Film Board. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://www.nfb.ca/film/owl_raven_eskimo_legend/.

- Igloliorte, Heather, 2010 “The Inuit of Our Imagination.” In Inuit Modern, edited by Gerald McMaster, 44–45. Toronto, Art Gallery of Ontario.

- Igloliorte, Heather, 2016 “Annie Pootoogook: 1969–2016.” Canadian Art. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://canadianart.ca/features/annie-pootoogook-1969-2016/.

- Igloliorte, Heather, 2017 “Curating Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Inuit Knowledge in the Qallunaat Art Museum.” Art Journal 76 (2): 100–113.

- Igloliorte, Heather, 2020 “Inuit Art is a Marker of Cultural Resilience.” Inuit Art Quarterly. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/iaq-online/inuit-art-is-a-marker-of-cultural-resilience.

- Ingold, Tim, 2011 The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London; New York: Routledge.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1974 to 1982 Inuit Today.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1975a “Is the Real Inuk on the Way Out?” Inuit Today 4 (2): 52–56.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1975b “Segregation in Frobisher says Housing Association.” Inuit Today 4 (3): 22–23.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1979 “The Strangers.” Inuit Today 7 (1): 19–24.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1980 “NWT Separates from Canada.” In Paper Stays Put: A Collection of Inuit Writing, edited by Robin Gedalof, 33–40. Edmonton, Hurtig Publishers.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1993 Arctic Dreams and Nightmares. Penticton, Theytus Books.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1995 “Thirsty for Life.” In Echoing Silence: Essays on Arctic Narrative, edited by George Moss, 93–101. Ottawa, University of Ottawa Press.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 1996 “Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border.” Studies in Canadian Literature 21 (2): 155–156.

- Ipellie, Alootook, 2001 “People of the Good Land.” In The Voice of the Natives, The Canadian North and Alaska, edited by Hans Blohm, 19–31. Toronto, Penumbra Press.

- Joo, Eungie, Joseph Keehn II, and Jenny Ham-Roberts (New Museum), 2011 Rethinking Contemporary Art and Multicultural Education. London; New York: Routledge.

- Kennedy, Michael P. J., 1996 “Alootook Ipellie: The Voice of an Inuk Artist.” Studies in Canadian Literature 21 (2): 157–164.

- Maire, Aurélie, 2015 “Dessiner, c’est parler”. Pratiques Figuratives, Représentations Symboliques et Enjeux Socio-Culturels des Arts Graphiques Inuit au Nunavut (Arctique Canadien). PhD diss., Université Laval, Québec et Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales, Paris.

- Murray, Karen Bridget, 2017 “The Violence Within: Canadian Modern Statehood and the Pan-territorial Residential School System Ideal.” Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 50 (3): 747–772.

- Prouty, Amy, 2018 “Dessiner La Résilience Satirique Des Inuits: Les Caricatures Décoloniales d’Alootook Ipellie.” Esse: Arts + Opinions, no. 93: 30–37.

- Qikiqtani Inuit Association, 2014 Qikiqtani Truth Commission Thematic Reports and Special Studies 1950–1975. Iqaluit, Inhabit Media.

- Tuck, Eve and Wayne Yang K., 2012 “Decolonization is not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1 (1): 1–40.

- Vizenor, Gerald Robert, ed., 2008 Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

List of figures

Figure 1

Alootook Ipellie at work

Figure 2

Selected “fillers” drawn by Alootook Ipellie in various issues of Inuit Today between 1974 and 1982.

Figure 3

The Nook family and the government in a rope-pulling game

Figure 4

Satirical drawing of the Northwest Territory (and Yukon) separating from Canada. The anthropomorphized map is literally walking away from Canada

Figure 5

Satirical cartoon criticizing the extractive industries

Figure 6

Illustration of the climate crisis

Figure 7

Juxtaposition of snow houses and government housing

Figure 8

Postcard of buildings painted in stripes in Pond Inlet

Figure 9

Cambridge Bay’s hotel illustrated as a multiple story snow house

Figure 10

Ipellie advocating for a health center in Kewatin, Nunavut

Figure 11

Houses disposed along and connected to an endless pipeline

Figure 12

Nanook building a snow house. Ice Box

Figure 13

A conversation between community members and a character on a tower regarding the placement of buildings.

Figure 14

Nanook gets a new jacket for the winter, but it doesn’t fit. Ice Box

Figure 15

walrus commenting on oil extraction and Canadian politics