Abstracts

Abstract

In 1851, during his stay in what was then Russian America, Finnish scientist Henrik Johan Holmberg (1818–1864) collected a unique assortment of some four hundred objects primarily from the Indigenous people of southern Alaska and the Northwest Coast. The collection included skin clothing, dress ornaments, hunting equipment, household tools, and ceremonial objects from the Koniags (of Kodiak Island off the coast of South Alaska) and the Tlingit (along the Pacific Northwest Coast). On his journey home in 1852, Holmberg visited Copenhagen and the Museum of Northern Antiquities (later the National Museum of Denmark). There, he met Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788–1865), museum director, Danish antiquarian, and creator of the so-called “three-period system,” which divided early human history into the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. Last, but not least, Thomsen founded the first ethnographic museum in the world. Thomsen, who never missed an opportunity to increase the museum’s collections, succeeded in buying Holmberg’s collection from him, perhaps because of Holmberg’s poor finances. The Holmberg Collection consists of unique specimens from a period before the Indigenous population was forever influenced by the cultural changes that were introduced with the early Russian trade. This article focuses the Holmberg Collection of skin clothing, which differed considerably from that of the more northerly Inuit people. The collection is part of the Danish National Museum’s interdisciplinary research initiative Northern Worlds, under the subproject “Skin Clothing from the North,” which includes the museum’s large collection of skin clothing from circumpolar Indigenous people.

Keywords:

- Rare skin clothing,

- documentation,

- Skin Clothing Online,

- Kodiak Island,

- Henrik Johan Holmberg

Résumé

En 1851, pendant son séjour dans ce qui était alors l’Amérique russe, Henrik Johan Holmberg (1818-1864), un scientifique finlandais, recueillit un assortiment unique d’environ 400 objets provenant principalement des Peuples autochtones du sud de l’Alaska et de la côte nord-ouest. La collection comprenait des vêtements en peau, des parures de vêtements, du matériel de chasse, des outils ménagers et des objets cérémoniels des Koniags (de l’île Kodiak au large du sud de l’Alaska) et des Tlingit (le long de la côte nord-ouest du Pacifique). Lors de son voyage de retour chez lui en 1852, Holmberg se rendit à Copenhague et au musée des antiquités du nord (devenu plus tard le Musée national du Danemark). Il y rencontra Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788-1865), directeur de musée, antiquaire danois et créateur du prétendu « système à trois périodes », qui divisait la première histoire de l’humanité en deux âges : l’âge de pierre, l’âge de bronze et l’âge de fer. Enfin, et surtout, Thomsen fonda le premier musée ethnographique au monde. Thomsen, qui n’a jamais manqué d’augmenter les collections du musée, réussit à racheter la collection de Holmberg, peut-être en raison de la situation financière précaire de Holmberg. La collection Holmberg est composée de spécimens uniques datant d’une période antérieure à l’influence prévisible de la population autochtone sur les changements culturels introduits lors du commerce précoce de la Russie. Cet article se concentre sur la collection de vêtements en peau Holmberg, qui diffère considérablement de celle des Inuit plus septentrionaux. La collection fait partie de l’initiative de recherche interdisciplinaire Northern World du Musée national danois, dans le cadre du sous-projet Vêtements de peau du Nord, qui comprend une vaste collection de vêtements de peau des Peuples autochtones circumpolaires.

Mots-clés:

- Vêtements de peau rares,

- documentation,

- Skin Clothing Online,

- île de Kodiak,

- Henrik Johan Holmberg

Article body

From 2009 to 2014, the National Museum of Denmark initiated a multidisciplinary research project titled Northern Worlds. “This initiative hopes to generate new insight and knowledge in culture and climatic change. It will also shed light on global networks by studying Northern cultures from the Ice Age hunters to the present day populations in the cold regions” (National Museum of Denmark, n.d.). The initiative included over twenty-five scientific projects in collaborations between Danish and foreign universities. One of the projects was Skin Clothing from the North.[1] It focused on the museum’s unique collection of about 2,170 single items of skin clothing from around 1840 until 1950, gathered among the circumpolar peoples of Greenland, Arctic Canada, Alaska, Siberia, and northern Scandinavia.[2] The aim of the study was to show the relationships among gender, animal skin types, manufacture, sewing, and design, on the one hand, and the circumpolar peoples’ way of life, geographical distribution, and interactions, as well as the influence of trade, on the other hand, before Indigenous Peoples had replaced skin garments with ordinary manufactured clothing. Among other works, the Danish archaeologist and cultural geographer Aage Gudmund Hatt’s (1884–1960) thesis Arktiske Skinddragter i Eurasien og Amerika: En etnografisk Studie from 1914 served as an important inspiration for the project. Hatt’s thesis was translated and published in English as “Skin Clothing in Eurasia and America: An Ethnographic Study” in Arctic Anthropology in 1969, more than fifty years after the original Danish publication.

During Skin Clothing from the North, a range of new documentation tools to enhance the research were developed: high-definition digital photography with zoom function for each item; movable three-dimensional photos of selected costumes; structured hierarchical description using database; methodical measurement of each item (Schmidt 2010a, 2010b, 2011, 2012, 2014); identification of species by means of DNA analyses (Gilbert 2010) and hair microscopy. Last but not least, a new method for pattern documentation, which uses three-dimensional non-destructive measurements of garments to produce precise two-dimensional patterns, was developed (Jensen 2010; Jensen Schmidt, and Petersen 2013).

In 2014 the entire collection was published on the website Skin Clothing Online. Since 2017 the website has been continually enriched with skin clothing from the Greenland National Museum and Archives (Schmidt 2016).

The Holmberg Collection of skin clothing is included in Skin Clothing from the North and Skin Clothing Online, as one of the Danish National Museum’s oldest and most important Alutiiq skin clothing from Alaska. First, however, it is necessary to introduce Holmberg, a gifted and interesting man in many ways, who was acting as an autodidact, original anthropologist.

Henrik Johan Holmberg[3]

On his journey home from Novo-Arkhangelsk[4] in Russian America in 1852, the Finnish geologist, naturalist, and ethnographer Henrik Johan Holmberg visited the Museum of Northern Antiquities (the later National Museum of Denmark) in Copenhagen. There, he met, by chance, the museum’s director, Christian Jürgensen Thomsen, which resulted in Thomsen acquiring Holmberg’s unique collection of skin clothing, dress ornaments, hunting equipment, household tools, and ceremonial objects from the Indigenous people in Russian America. It is not obvious what Holmberg’s original intent for the collection was. When Thomsen offered him a substantial amount of money, Holmberg possibly saw a chance to improve his strained finances.

Henrik Johan Holmberg was born in 1818, the son of a minister of the church on Hamnö Island, one of the Kökar Islands south of the Finnish Åland Islands. From the age of three he was raised with his family in Reval (Tallin), where he learned to speak German fluently and showed a talent for writing poetry and playing several musical instruments. From 1839 he studied chemistry and mineralogy at the Imperial Alexander University in Helsingfors (Helsinki). Later Holmberg was employed as a mining engineer in the Finnish mining industry. In 1845 he was sent to the Ural Mountains to study gold mining methods, and in 1849 he decided to go to California on behalf of a private prospecting corporation Kaliforniska Bolaget, as a consultant on gold mining methods. He was accompanied by his wife, Katarina, and geologist Fredrik Christian Frankenhaeuser (1820–1888). Holmberg’s manservant, August Isak Renlund, and his wife’s maid went with them. They sailed from Åbo (Turku) in Finland to Valparaiso in Chile. When they arrived there at the beginning of 1850, rumours of lawless conditions in California made Holmberg change his plans; instead of going to San Francisco, Holmberg and his companions sailed to Novo-Arkhangelsk in Russian America, where Frankenhaeuser’s brother was a physician employed by the Russian-American Company (RAC).

From 1799 until 1861, the RAC regulated fur trading, mining, and other commercial enterprises in Russian America and along the Pacific Northwest Coast. In April 1850 Holmberg and his travelling companions landed in Novo-Arkhangelsk, where they learned that the previous winter the RAC in California had mined no less than thirty-one kilos of gold. Holmberg and Frankenhaeuser hoped to join the subsequent gold rush, but it was impossible to get passage to San Francisco before Christmas of 1850. Holmberg passed the time by making a comprehensive study of the language, behaviour, and material culture of the native population in Russian America. He also studied the history of the RAC.

In December 1850 Holmberg’s wife and her maid returned by ship to Europe, and in January 1851 the men left for San Francisco, where it turned out that conditions in the gold-digging area in California were still chaotic and lawless, and Holmberg’s expertise in gold washing was unmarketable. After a month spent in Hawaii, Holmberg and his companions returned to Novo-Arkhangelsk. They had now run out of money, and in Novo-Arkhangelsk the governor took advantage of their unfortunate situation and sent them to Kodiak Island and the Kenai Peninsula prospecting for coal fields.

In December 1851 Holmberg and his companions succeeded in travelling home from Novo-Arkhangelsk on board a vessel belonging to the RAC. After their unsuccessful gold-digging adventure, the men returned safely to Finland in September 1852, rich in experience and with a large collection of insects and fish specimens. Holmberg made a substantial material culture collection on Kodiak Island while Frankenhaeuser managed to amass a beetle collection at the Kenai Peninsula. Altogether, the two gathered some nineteen thousand insects and a number of fish collected during their journeys in Chile, California, and Russian America. The biological material was later donated to the University Museum of Helsingfors (Birket-Smith 1941; Falk 1985; Enckell 2007).

En route home Holmberg paid a visit to the Museum of Northern Antiquities in Copenhagen (Birket-Smith 1941).

The Museum of Northern Antiquities and Christian Jürgensen Thomsen

The Museum of Northern Antiquities, which opened in 1819, was directed by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788–1865), an innovative and inspiring curator, from 1819 until 1865. Thomsen, the son of a wealthy merchant from Copenhagen, never acquired an academic degree, but conducted the management of the museum in a new and exemplary way. For instance, the Museum’s Archaeological Objects were exhibited according to Thomsen’s initial ideas of the three-period system—Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age—in nordic prehistory. Thomsen published his scientific thoughts in Ledetraad Til Nordisk Oldkyndighed (Guidelines to Scandinavian Antiquity) in 1836.

In 1849 Thomsen created the Ethnographic Museum, which was the first of its kind in the world. The museum was placed near the premises of the Museum of Northern Antiquities in the Mansion Prinsens Palais, where the National Museum is still located today. The Danish Archaeologist Jørgen Jensen (1936–2008) describes how the Ethnographic Museum displayed objects from overseas cultures from Greenland, China, Japan, and South America. Thomsen divided the ethnographic collections according to the supposed abilities of the Native populations: first, the wild peoples who were unable to use metals; second, the peoples who used metal but had no literature; and third, the peoples who possessed both abilities. The peoples were further divided according to their climatic living conditions: the cold climate, the temperate climate, and the hot climate (Jensen 1992, 351). The earliest ethnographic objects derived from the Indian Cabinet in the Royal Kunstkammer, which was founded around 1650 by King Frederik III (1609–1670). Archaeological objects from Greenland, which were originally catalogued in the Museum of Northern Antiquities, were transferred to the new Ethnographic Museum.

Thomsen was well aware that knowledge of the material culture of “Wild Natives” was a key to understanding the three-period system with regards to nordic prehistory (Jensen 1992, 350). Thanks to Thomsen’s acknowledged talent for arousing public interest in the new museum ideas, his enthusiastic approach and his energetic leadership, the foreign collections increased. New acquisitions for the Ethnographic Museum were made at an early stage when familiarity with foreigners had not irrevocably changed the Indigenous material culture. Especially in Greenland, Danish officials were encouraged to collect archaeological and ethnographic objects from the daily life of the Inuit as well as remains from the Norse settlements. The many items of clothing, utensils, and means of transport required ever greater amounts of space in the new museum. Thomsen repeatedly succeeded in finding financial support for the enlargement of the Ethnographic Museum, even in the face of mounting opposition from members of the Danish Parliament. Minister of War A.F. Tscherning, for example, expressed his reluctance: “Because of one man’s excellence and kindness and because of these boats…It is not kayaks we live by” (Jensen 1992, 374).

The Meeting in Copenhagen between Holmberg and Thomsen

A series of six letters from Holmberg to Thomsen (Holmberg 1852–1855), now deposited in the archives of the National Museum, leaves a vivid impression of the 1852 meeting between the two that resulted in the purchase of Holmberg’s ethnographic collection from the Aleutian Islands, Kodiak Island, and the Northwest Coast of America. In his thorough review of the correspondence, Birket-Smith (1941, 122) concluded that the foreign guest was noticed by Thomsen, who “engaged in conversation with him—as was his habit—and ultimately invited him to his home…He must have been eager to seize the opportunity of acquiring corresponding material from the opposite extremity of the Inuit area.” The invoice for the purchase of the total Holmberg collection, dated March 31, 1854, can still be found in the Archives of Ethnographic Collection. Thomsen paid Holmberg the substantial sum of 300 Rdr (rix-dollars)[5] for the collection. According to Birket-Smith, the Holmberg Collection comprised 400 items from Kodiak Island (from Alutiiq people) and the Tlinglit as well as a few items from the Aglemiut Inuit, and the Aleuts (122).

In his last known letter to Thomsen, dated September 25, 1855, Holmberg describes how the Danish museum aroused his interest in the prehistory of Finland: “It was now his intention to gather the scattered remains from that period in the University Museum [of Helsingfors].” In 1855 Holmberg published his Ethnographische Skizzen über Volker des russischen Amerika from his journeys in Russian America.[6]

As a result of Holmberg’s acquaintance with Thomsen, Holmberg published papers on Finnish prehistory together with an illustrated catalogue from the collections at the University Museum in Helsingfors. In 1860 Holmberg was appointed the first inspector of the Finnish fisheries. He died in 1864 of tuberculosis at the age of forty-seven (Enckell 2007).

Kodiak Island and Its Inhabitants

Kodiak Island is the largest island in the Kodiak Archipelago (and in Alaska), covering an area of about nine thousand square kilometres. The landscape is very rugged, with tall mountains and large forests, moors, and tundra. The coast has deep, ice-free bays that provide sheltered anchorages for boats. The climate is moist and rough (Birket-Smith 1941, 122).

The Indigenous population of Kodiak Island—the Koniags[7]—belong to Inuit stock, and the language and culture is closely related to those of the Chugach of Prince William Sound. Their own name for themselves was said to be Koniagmiut or Kanagist, but they also called themselves “Soo-oo-it,” possibly the ordinary word for Inuit in the South Alaskan dialect “juit” (Yuit).[8] The Danish explorer Vitus Bering was the first European to discover Kodiak Island, in 1741, and was followed by the Russian Stephan Glotov, who wintered on Kodiak Island in 1763 and barely succeeded in escaping from the island after serious conflicts with the Natives. In 1783 the Russian merchant Grigori Shelekhov established a private trading post on Kodiak Island, and for many years it remained the centre of Russian commercial trade east of the Aleutians. Russian Orthodox missionaries introduced Christianity to the Native population, but a hundred years later the Natives still clung to their ancient customs (Birket-Smith 1941, 123–24). When Holmberg visited the island, the population had declined greatly to as few as 1,500 individuals because of tuberculosis and other diseases (Holmberg 1855, 77).

The Koniags were generally taller than other Natives and some had a copper-brown skin, black hair, high cheekbones, and shining white teeth (Holmberg 1855, 80). The Koniags lived by hunting sea mammals, whaling, and fishing, following seasonal opportunities. Important animals were seal, sea lion, sea otter, halibut, and various species of salmon (Birket-Smith 1941, 124). The baidarka, a one- or two-seated sealskin kayak, was used for hunting and travelling. Like other Pacific Inuit, the Koniags had communal winter houses for three or four families, made of timber and provided with a steam bath room, probably borrowed from the Russians. Early observers of the population noted the existence of “homosexual” behaviour, since it was common for young men to dress like young women and to perform their work (126).

In general the Natives of the Pacific area dressed quite differently from the Inuit of Canada and Greenland (Birket-Smith 1941, 124). This is not surprising since, contrary to Holmberg’s assumption, the Yupik were an extension of the Inuit rather than a separate population. At one time the clothing of men and women on Kodiak Island had been the same (Holmberg 1855, 84). The parka was a long shirt-like garment with a small neck opening for the head. The parka reached down to the feet, covering the upper and part of the lower body. As late as the latter part of the nineteenth century the parka was either made of mammal pelts (Spermophilus, sea otter, bear, and reindeer) or bird skins (Alca and Phalacrocorax species). Spermophilus was not found on Kodiak Island, but on adjacent smaller islands. Parkas of Spermophilus were the most common (85).

The use of small animals’ skins for clothing predominated in the southwestern parts of Alaska, on Kodiak Island and on the Aleutian Islands. The skins of small animals had great influence on the cut and design, which deviated from all other Inuit clothing designs. Parkas of large animals’ skin were not found in museums’ collections from these peoples, even though sealskin and skin from sea otter were used for women’s clothing, and caribou skin was bought by the Konjags for parkas. The furred parkas of small animals had no hood. Perhaps the hoodless design, perhaps derived from the earliest settlements, had survived in remote Alaskan areas, or the hood was not necessary because of the milder climate on Kodiak Island (Hatt 1969, 48–51). The presence of collars in parkas made of bird skin and gut skin may have been a Russian military influence (49).

However, since the settlement by the Russians, the inhabitants had been denied the use of sea otter and bear pelts because they were valued in international trade; European styles of clothing and materials were displacing the old garment types (Holmberg 1855, 87–88).

The kamleika, made of waterproof gut skin from bear, sea lion, or seal, served as a raincoat over the parka during sailing and in wet weather. Compared with the parka, the kamleika had wider and longer sleeves as well as a hood. The garment was decorated with reindeer hair and feathers. The design of the parka and the kamleika had changed little up to the 1850s, but decorations of red wool and strips of cloth were now added. Kamleikas in fragile gut skin from sea otter were made for the Russian state authorities; gut skin from bear was considered the strongest, but was hard to get hold of. Gut skin from sea lion was the most commonly used material (Holmberg 1855, 86–87).

Birket-Smith (1941, 124–25) mentions that instead of trousers, the men of southwest Alaska wore a genital covering, but Hatt (1969, 64) states that men occasionally wore trousers. Until the Russians arrived, all of them, according to Holmberg, went bare footed. Afterwards, boots, called balaena, made of leather from seal and with whale skin soles were common (Holmberg 1855, 89). A peaked cap with shadow, made from roots, and decorated with beads, dentalium shells and sea lion whiskers was commonly worn (88).

Ornaments were inserted in the lips and the septum of the nose. Dentalium shells and amber, used for ornaments, were highly valued (Birket-Smith 1941, 124–25). Holmberg (1855, 81–82) recounts to Dawydow that, in 1802, two dentalium shells were paid for a coat of marmot (Spermophilus) skin. When Holmberg was on Kodiak Island, he saw elderly women with tattooed cheeks. On festive occasions, the Natives painted their faces in red and black (83).

Items from the Holmberg Collection

In the following account, the eight items of skin clothing in the Holmberg Collection are described in detail on the basis of the current research conducted in the project Skin Clothing from the North (Schmidt 2012), as well as Birket-Smith’s (1941) remarks. It is striking that Hatt mentions only a pair of boots from the Holmberg Collection in his 1914 thesis. He gives a detailed description of Alaskan people’s clothing in the earlier stages, even though “the museum material in this respect is very sparse” (1969, 49). In the following, for all items, reference is made to Hatt whenever parallel clothing items are described.

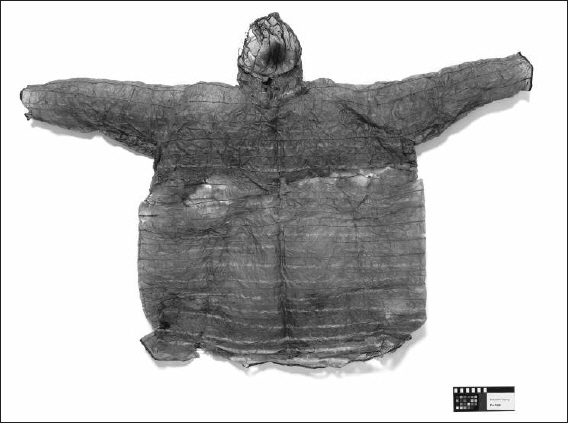

Man’s parka of marmot skin. Inventory number Ic.190 (Ic.190.3)

“Man’s costume (Akuku)[9] worn by the Koniags in Kodiak; in the shape of a blouse and consisting of a double layer of skin from the American marmot (Spermophilus) such that the belly skin forms the inside, the back the upper part, and the tail a kind of loose-hanging decoration” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).[10]

The man’s parka, made of approximately 80 marmot skins, has the hair side turned both outwards and inwards (Figure 1). The hoodless parka consists of a rectangular body design, yoke, and sleeves. The body is made of three horizontal bands, each of 20 animal skins with loose tails as decoration. A yoke made of 10 skins covers the shoulders and leaves an opening for the neck. Very narrow, rather short sleeves have long slits in the armpits, making it possible to pass the arms through. On the outside, rectangular pieces of marmot back skin (c. 23 × 8 cm) are sewn together with a running stitch in horizontal bands. Back skins are positioned with the remaining eyeholes turned upwards and tails turned downwards. The parka is lined with irregular belly skins with remaining limbs. The tops of the (inner) belly skins are sewn together horizontally with the tops of the (outer) back skins in running stitch. The bottoms of the belly skins are attached with a few stitches to the bottoms of the back skins (Birket-Smith 1941, 126–27).

Figure 1

Man’s parka of marmot skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.190 (Ic.190.3)

A comparable parka (Etholéns Collection, inventory number 86) made of Spermophilus was found in the National Museum of Finland by Hatt, who described the same sewn-together construction of the outer and inner fur. The front and back of the parka were identical in size and the sleeves were too narrow for use; a split in the armpit made it possible to pass the arms through. The hoodless parka could be used by both men and women, and the type was only known on Kodiak Island, where it was regarded as an older, primitive design; the utilization of the small animal skins and the sewing technique were, by all accounts, very skilful (Hatt 1969, 50).

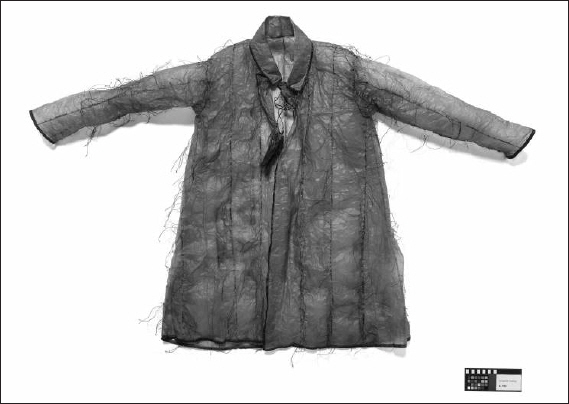

Woman’s parka of cormorant skin. Inventory number Ic.191

“Sunday costume for women of the same tribe as Ic.190 called ‘the Koniags in Kodiak’/; it has the same shape, but consists of only one layer of skin from a cormorant (Phalacrocorax). Collar, edgings and decorations are made of bright red cloth” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

The woman’s parka, with the feather side turned outwards, is made of approximately 40 cormorant skins (Figure 2). The hoodless parka consists of a rectangular body design, and a yoke with collar and sleeves. The body consists of three horizontal bands, each made of eight bird skins. A yoke covers the shoulders; the sleeves are narrow. Red woollen textile has been used for the high, upright collar, the edging of the sleeves, and as part of the lower edging. The collar is lined with undyed textile of cotton. From the seams, numerous tassels of double narrow strips of red cloth with small tufts of white hair hang at the ends in the middle. The bird-skin parka was rather valuable. Holmberg says in one of his letters that he had to pay 21 silver rubles for it (Birket-Smith 1941, 127).

Figure 2

Woman’s parka of cormorant skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.191

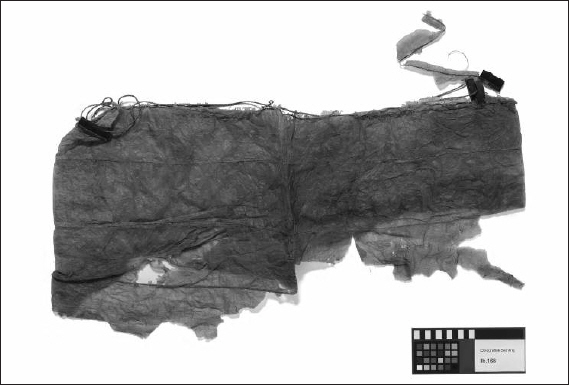

Man’s parka of gut skin. Inventory number Ic.192 (Pu.180)

“Two parkas, made of gut skin from sea lion; the Koniags wear them over the common parka when they row in their baidarkas” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

The man’s parka or kamleika is made of translucent gut skin, probably from sea lion (Figure 3). The hooded kamleika consists of a rectangular body design with continuous sleeves. The horizontal sewing of the gut skin in running stitch, approximately 40 stitches per 10 cm, runs through the folded edges of the gut strips and is turned inwards; it is sewn with sinew. The gut strips are between 5 and 6 cm wide. Here and there, decorative little tufts of red and black woollen thread are inserted in the sewing. The hood opening has a gut-skin edging and a plaited drawstring of sinew. The sleeves and lower part are edged with a narrow band of dyed skin. The kamleika is particularly torn in the middle where it has been bent during storage. Some other parts are also damaged.

Figure 3

Man’s kamleika of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.192 (Pu.180)

There were two designs of hooded gut-skin parkas among the Inuit. In the eastern areas, where the oldest designs were found, gut skins were only sewn vertically, while in the western Inuit areas, horizontal sewing of the gut skins was prevalent (Hatt 1969, 52–55).

According to the accession reports, the Holmberg Collection contained five gut-skin parkas and coats (Ic.192, Ic.193, Ic.194, and Ic.195), but only one gut-skin coat (Ic.195) was identified with certainty at the National Museum in 1941 (Birket-Smith 1941, 128). One parka with hood, today numbered Pu.180, may be one of the pair of sea lion gut-skin parkas originally numbered as Ic.192.

Gut skin coat in European style. Inventory number Ic.195

“A coat of the same shape as No. 194, but sewn from the brown bear’s guts, and more beautifully decorated with loose laces” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

The coat in European style is made of translucent gut skin from the brown bear (Figure 4). The coat, designed in a bell shape, is open at the front and has a downturned collar and narrow sleeves. The vertical sewing of the gut skin in running stitch, approximately 40 stitches per 10 cm, runs through the folded edges of the gut strips and is turned inwards; it is sewn with sinew. Edging at collar, sleeves, front opening and lower edging are in dyed gut skin and sewn in running stitch with a commercially produced red and white thread. A plaited/woven drawstring of the same thread with long tassels of hair and yarn closes the coat at the neck. Short woollen tufts, strings, and long hairs are sewn decoratively in the seams (Birket-Smith 1941, 127).

Figure 4

A coat of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.195

Cap cover made of sea lion gut. Inventory number Ic.196

“A cover for a cap in the shape of a Russian military hat is made of sea lion gut and with beautifully sewn piece of dyed skin” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

The cap cover is made of opaque, dyed sea lion gut (Figure 5). The cap holds a symmetrical design, more or less Europeanized, with a broad brim with stripes of red- and black-dyed gut skin, sewn to a voluminous crown decorated with dyed gut skin in black and red in concentric circles. On top of the crown is an application in the shape of a Maltese cross in black- and red-dyed gut skin. Hanging from the edge of the disc are broad tongues of black- and red-dyed gut skin. The crown is decoratively stitched, probably with split hairs from caribou. The seams are in running stitch, approximately 24 stitches per 10 cm. The gut strips are approximately 5 cm wide (Birket-Smith 1941, 129).

Figure 5

A cap cover of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.196

Cap cover of sea lion gut. Inventory number Ic.197

“A cover for a cap in the shape of a Russian military hat like number 196; made of sea lion gut” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

The cap cover is made of opaque, dyed sea lion gut (Figure 6). The cap has a symmetrical design, more or less Europeanized, with a brim; a stripe of black-dyed gut skin, sewn to a crown decorated with dyed gut skin in black and red in smaller concentric circles. On top of the crown a green-dyed gut-skin disc with a yellow Maltese cross and a red cross in gut skin has been placed. Hanging from the edge of the disc are broad tongues of black- and red-dyed gut skin. The crown is decoratively embroidered with split hairs, probably from caribou. The seams are in running stitch, approximately 24 stitches per 10 cm. The gut strips are approximately 5 cm wide (Birket-Smith 1941, 129).

Figure6

A cap cover of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.197

Man’s boots. Inventory number Ic.210

“A pair of man’s boots with white legs and black uppers. The soles are often made of whale skin and the legs of seal skin, especially from the neck” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

Figure 7

A pair of man’s boots, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.210

The pair of man’s boots is made of light de-haired skin from caribou used for the leg, black de-haired skin with epidermis, probably commercially tanned, is used for the uppers, which have chequered carvings on the surface (Figure 7). The soles are made of de-haired seal skin. Between the upper and the sole, and at the leg, there is a peep edge of light de-haired skin. The sewing between the upper and the leg is in double running stitch, 50 stitches per 10 cm. Sewing, including peep edge, is in running stitch, 30 stitches per 10 cm. The leg has no edging (Birket-Smith 1941, 132). Boots from Kodiak Island and the Aleutian Islands had no loops for tying straps (Hatt 1969, 85). Hatt termed Ic.210 “shoe-boots.” Considering the size, they were probably made for a woman. The construction of the boots was influenced by northeast Siberian design (86).

Man’s skin belt for kayaking. Inventory number Ib.168

“A kind of belt, made of gut skin; it is called ‘Akwilidak’ and is used by the natives when they sail their baidarkas, in order to prevent water penetrating, by tying the top edging of the belt around the waist, and the lower edging around the ring of the baidarka” (Ethnographic Collection’s accession report 1853).

The man’s belt for kayaking is made of gut skin (Figure 8). The clothing item was used as a tubular belt when sailing the baidarka. Tightened over the baidarka’s manhole ring and round the kamleika’s waist area, the belt for kayaking made a watertight connection. The gut strips are between 10 and 12 cm wide, sewn horizontally with running stitch, approximately 40 stitches per 10 cm. Deer hair has been decoratively inserted in the sewing at the edging. A plaited drawstring of sinew runs through straps of de-haired, probably tanned skin. The item is damaged as a result of improper storage and insect attacks.

Figure 8

Man’s belt for kayaking, made of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ib.168

Discussion and Conclusion

Most of the circumpolar skin clothing collection at the National Museum derives from Greenland, and comprises about 900 single items: headgear, parkas, trousers, footwear, mittens. made of a variety of skin types from marine and terrestrial animals as well as birds. Most of the items were gathered at end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century by a succession of Danish company employees. About 850 comparable items derive from Canada and Alaska, collected for the most part by the Arctic explorer Knud Rasmussen (1879–1933) and Birket-Smith during the Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–24 through Arctic Canada and Alaska. About 430 items derive from the Siberian peoples, a few of whose garments are made of fish skin, and from the Sami people. The Siberian collection was mainly procured as purchases from collectors or exchanges with other museums in the first half of the twentieth century, while the Sami collection is generally older.

In the Ethnographic Collection’s accession reports on the purchase of the Holmberg Collection in 1853, a total of twelve skin clothing from Kodiak Island were listed: two parkas (Ic.190 and Ic.191), five gut-skin parkas/coats (Ic.193–195), two caps (Ic.196–197), a pair of boots (Ic.210), and a belt for kayaking (Ib.168). Seven items were described in 1941 by Birket-Smith (1941, 128), who wrote, “There are two other specimens, one of which is badly torn, without numbers, which may have come from him, but this is impossible to decide at the present time. Probably several specimens of these fragile objects have been damaged and have disappeared in the lapse of time.”

One of the pair of missing gut-skin parkas (Ic.193) has in all probability been identified at the National Museum. One recently identified parka (EUM 132) at the Ethnographic Museum in Oslo, donated in 1863 to the Norwegian museum by Thomsen, is probably not part of the original Holmberg Collection. The belt for kayaking (Ib.168) was also identified the National Museum during the present research.

The items still missing are one gut skin parka (Ic.192) and two gut-skin coats (Ic.194–195), unfortunately still unidentifiable in the collection of gut-skin clothing items. The great fragility of the material and its attraction for insect pests are possible reasons for its decomposition and destruction.

The Holmberg Collection of skin clothing from Kodiak Island represents an early and exclusive collection at the National Museum, gathered around 165 years ago. Even though the collection today includes fewer clothing items, important information was gained during the Skin Clothing from the North project. Further study on prehistoric and historic skin clothing collections—in cooperation with museums and Indigenous societies—will hopefully make it possible to compile even more important knowledge of original clothing from the remote circumpolar areas.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I thank Hans Christian Gulløv for his kind collaboration on this article and Eva Meyer of the Ålands Emigrantinstitut for her assistance with literature.

Notes

-

[1]

See National Museum of Denmark, n.d., “Skin Clothing from the North,” accessed November 14, 2018, http://nordligeverdener.natmus.dk/en/research-initiatives/descriptions-of-the-projects/skin-clothing-from-the-north/.

-

[2]

A pair of boots, stockings, and mittens count as two single items.

-

[3]

This representation of Holmberg is based on the account of him by Danish anthropologist Kaj Birket-Smith (1893–1977), the head of the Ethnographic Collections from 1940 to 1961 (Birket-Smith 1941). I have also drawn on the introductory essay on Holmberg by Marvin W. Falk (1985), professor of library science at the University of Alaska, and the research conducted by the Finnish MFA Maria Jarlsdotter Enckell (2007) in connection with an exhibition at the Ålands Emigrantinstitut (2007–2010).

-

[4]

Novo-Arkhangelsk was renamed Sitka in 1867, when Russian America (Alaska) was sold to the United States.

-

[5]

The rix-dollar was the currency in use in Denmark until 1875, after which one rigsdaler was converted into two kroner.

-

[6]

In 1985 Holmberg’s translated works were published by the University of Alaska under the title Holmberg’s Ethnographic Sketches, edited by M.W. Falk. The sketches concerning the Tlinglit of the Pacific North West coast and the Koniags of Kodiak Island consist of descriptions, narratives, and personal observations integrated with information from earlier publications, and were intended as popular edification for his fellow Finns, since Holmberg was not a trained ethnologist. Nevertheless, Falk (1985, ix) remarks in his introduction to Holmberg’s Ethnographic Sketches that “his [Holmberg’s] original material, accounts of oral traditions and personal observations, has been treated as primary source material by several generations of scholars.” Falk also includes Holmberg’s description of the development of the RAC (71–103).

-

[7]

The Koniags are the Alutiiq people, belonging to the Yupik people in Alaska.

-

[8]

Today, the Alutiiq people are also called Sugpiaq (plural often Sugpiat).

-

[9 ]

Holmberg (1855, 84) gives the word as Átkukŭ

-

[10]

All translations from Danish to English are by the author.

Archival Sources

- Anon, 1853 Ethnographic Collection’s accession report. Register I. Ethnographic Collection, National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

- Holmberg, Henrik Johan, 1852–1855 Six letters to Thomsen, C.J., dated 1 March 1853, 4 May 1853, 26 June 1853, 18 August 1853, 12 September 1853, 25 September 1855. Archives of the Ethnographic Collection, National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

References

- Birket-Smith, Kaj, 1941 “Early Collections from the Pacific Eskimo.” In Etnografiske Blade, edited by Kaj Birket-Smith, 121–63. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseets Skrifter, Etnografisk Raekke 1.

- Enckell, Maria Jarlsdotter, 2007 “Henrik Johan Holmberg (1818–1864).” Exhibition text in 1721–1922: Two Centuries of Finnish Labor Migration to Imperial Russia. Produced for Ålands Emigrantinstitut and Ålands Museum, 2007–2010.

- Falk, Marvin W., 1985 Holmberg’s Ethnographic Sketches. Edited by M.W. Falk. Translated by F. Jaensch. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Gilbert, Tom, 2010 “DNA Insights from Ancient Hair.” In Skin Clothing from the North: Abstracts from the Seminar at the National Museum of Denmark, November 26–27, 2009, edited by Anne Lisbeth Schmidt and Karen Byrnjolf Petersen, 13. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Hatt, Aage Gudmund, 1914 Arktiske Skinddragter i Eurasien og Amerika: En etnografisk Studie. Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz Forlagsboghandel.

- Hatt, Gudmund, 1969 “Arctic Skin Clothing in Eurasia and America an Ethnographic Study.” Translated by K. Taylor. Arctic Anthropology 5 (2): 3–132.

- Holmberg, Henrik Johan., 1855. Ethnographische Skizzen Über die Völker des Russischen Amerika. Helsingfors: Gedruckt bei H.C. Friis.

- Jensen, Karsten, 2010 “Automated Construction of Sewing Patterns.” In Skin Clothing from the North. Abstracts from the seminar at the National Museum of Denmark, November 26–27 2009, edited by Anne Lisbeth Schmidt and Karen Byrnjolf Petersen, 16. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Jensen, Karsten, Anne Lisbeth Schmidt, and Anette Hjelm Petersen, 2013 “Analysis of Traditional Historic Clothing: Automated Production of a Two-Dimensional Pattern.” Archaeometry 55 (5): 974–92.

- Jensen, Jørgen, 1992 Thomsens Museum: Historien om Nationalmuseet. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel.

- National Museum of Denmark, n.d. “Northern Worlds.” Accessed November 14, 2018. http://nordligeverdener.natmus.dk/en/home.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth, 2010a “Skin Clothing from the North.” In Skin Clothing from the North: Abstracts from the Seminar at the National Museum of Denmark, November 26–27 2009, edited by Anne Lisbeth Schmidt and Karen Byrnjolf Petersen, 10–11. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark. Accessed November 15, 2018. http://nordligeverdener.natmus.dk/fileadmin/site_upload/nordlige_verdener/pdf/Skin_Clothing_From_The_North.pdf.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth, 2010b Skin Clothing from the North. Accessed November 15, 2018. http://nordligeverdener.natmus.dk/forskningsinitiativer/samlet_projektoversigt/skinddragter_fra_nord/language/uk/#c7394.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth, 2011 “Skinddragter fra Nord.” In Nordlige Verdener – aendringer og udfordringer. Rapport fra workshop 1 på Nationalmuseet 29 September 2010, edited by H.C. Gulløv, C. Paulsen, and B. Rønne, 114–18. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth, 2012 “Skin Clothing from the North.” In Challenges and Solutions, Northern Worlds: Report from Workshop 2 at the National Museum, 1 November 2011, edited by H.C. Gulløv, P.A. Toft and C.P. Hansgaard, 205–08. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth, 2014 “Skin Clothing from the North: New Insights into the Collections of the National Museum.” In Northern Worlds – Landscapes, Interactions and Dynamics: Research at the National Museum of Denmark. Proceedings of the Northern Worlds Conference 28–30 November 2012, edited by Hans Christian Gulløv, 273–92. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth, 2016 “The SkinBase Project: Providing 3D Virtual Access to Indigenous Skin Clothing Collections from the Circumpolar Area.” Études Inuit Studies 40 (2): 189–203.

- Skin Clothing Online, n.d. Accessed November 15, 2018. http://skinddragter.natmus.dk/?Language=0.

- Thomsen, Christian Jürgensen, 1836 Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftsselskab.

List of figures

Figure 1

Man’s parka of marmot skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.190 (Ic.190.3)

Figure 2

Woman’s parka of cormorant skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.191

Figure 3

Man’s kamleika of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.192 (Pu.180)

Figure 4

A coat of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.195

Figure 5

A cap cover of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.196

Figure6

A cap cover of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.197

Figure 7

A pair of man’s boots, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ic.210

Figure 8

Man’s belt for kayaking, made of gut skin, from the Holmberg Collection. Inventory number Ib.168

10.7202/1055438ar

10.7202/1055438ar