Abstracts

Abstract

This article is the result of an investigation about an unrecorded archaeological find in Cap St-Louis (New Brunswick) in 1940. The find was a Copper Kettle Burial as it was practiced by the Mi’gmaq during the 16th and 17th century. No proper recording or conservation efforts had been deployed then since the Copper Kettle Burial was not well known at the time. Most of the funerary objects have been lost or given as mementos to family or friends of finder. The site has been eroded since 1940 but this investigation permitted Parks Canada to assign it a provenience number and ensure proper protection in the future for the site in case other burials appears at this location. Some objects are located at the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton. In the spirit of reconciliation, the university will give back these funerary objects to the Mi’gmaq of New Brunswick.

Résumé

Cet article est le résultat d’une enquête sur une découverte archéologique non enregistrée au Cap St-Louis (Nouveau-Brunswick) en 1940. Il s’agissait d’une sépulture à la bouilloire de cuivre telle qu’elle était pratiquée par les Mi’gmaq au cours des XVIe et XVIIe siècles. Aucun effort d’enregistrement ou de conservation n’avait été déployé à ce moment-là, car l’enterrement de la bouilloire de cuivre n’était pas un phénomène bien connu à l’époque. La plupart des objets funéraires ont été perdus ou donnés en souvenir à la famille ou aux amis du découvreur. Le site est érodé depuis 1940 mais cette enquête a permis à Parcs Canada de lui attribuer un numéro de provenance et d’assurer une protection adéquate à l’avenir pour le site au cas où d’autres sépultures se produiraient à cet endroit. Certains objets se trouvent au Musée acadien de l’Université de Moncton. Dans un esprit de réconciliation, l’université remettra ces objets funéraires aux Mi’gmaq du Nouveau-Brunswick.

Article body

Introduction

Late in the summer of 1940, more precisely during the night of September 16th, a large storm hit the east coast of New Brunswick and created havoc.[1] The storm was called the Halifax Hurricane (ECCC 2009). Strong winds and high waves created a lot of material damage along the coast of Northumberland Strait.

On September 19th, 1940, the newspaper La voix d’Évangeline reported 50 lobster boats were sunk at Cape Bald in the Northumberland Strait (AFCEAAC). This storm also exposed some archaeological features in what was known as the village of Cap St-Louis (now part of Kouchibouguac National Park) located on the south side of the Kouchibouguacis River or the St-Louis River as it was called at the time. The next morning, September 17th, a fisherman/farmer Dominique Martin from Cap St-Louis, near the village of St-Louis de Kent in Kent County, went to inspect his boat after the storm and found objects protruding from the bank. A closer look and some digging revealed an overturned copper kettle, measuring 28 inches in diameter at the rim and 12 inches deep. Underneath the kettle was another smaller one, measuring 7 inches in diameter, thirteen iron axes, one knife, one stiletto (iron spike), several kettle handles and several fireplace hooks (crochets de crémaillères) and trade beads. There was also a human skeleton rolled into animal furs and birch bark with a sword (Daigle 1948: 162). This contemporary narrative fits very well the description of an Indigenous Copper Kettle Burial site as observed during the proto-historic period along the east coast of Canada and the Great Lakes area (Fitzgerald et al. 1993: 44; Whitehead 1993: 23; Delmas 2016: 92) and particularly among the Mi’gmaq of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (Whitehead 1993: 84-86; Turgeon 1997: 7-17; Harper 1956; Erskine 1959: 443). The objects constituting this burial site, as described above, are considered funerary objects and should be treated and referred to as such.

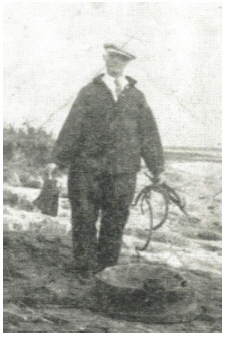

The picture in Figure 1 was published in Cyriac Daigle’s book Histoire de St-Louis in 1948. The date of the picture is unknown. It was probably taken by the author Cyriac Daigle himself or by a local photographer, Apollinaire Poirier, prior to 1948 for the book. We can identify some of the funerary objects found by Mr. Martin, which were probably still in his possession at the time the picture was taken. The copper kettle is overturned in its original position and a “small copper pot” seems to be inverted in its concave “punched-in bottom.” Mr. Martin holds two axes in his left hand and what seems to be three kettle handles, a kitchen hook (crémaillère) and one iron stiletto in his right hand. He is standing at the shore edge probably near or at the spot where he found the burial site. Dr. Clarence Webster, from Shediac, sent the contents of the find to the St-John Museum for analysis, which indicated the objects were probably of French origin and some 300 years old (Dominique Martin 1966). The Copper Kettle Burial phenomenon had not been studied yet and was not known in 1940.

Figure 1

Mr. Dominique Martin with some of the funerary objects recovered after a storm in 1940, Cap-St-Louis

This find, although popular at the time, was never properly recorded in any archaeological databases. Research showed no results of existing records with NB archaeological Services, the NB Museum in St-John or the National Museum of History in Gatineau. Only the Museé Acadien de l’Université de Moncton had funerary objects but very little context. The Cap St-Louis find was briefly discussed in an article about Copper Kettle Burials in New Brsunwick (Degrâce 1984: 43). The site was also included in a regional map of the Copper Burial sites in the Maritimes (Delmas 2016: 93) but was never studied in more detail.

The objectives of this investigation were as follows:

To officially register the site (with a provenience number) so as to be recognized as an archaeological site in Kouchibouguac National Park and offered proper protection in the future by Parks Canada.

To attempt to recreate the most accurate inventory of the funerary objects found with the burial.

To attempt to locate extant funerary objects from this find through existing museum and private collections.

Methodology

This investigation used several sources to attempt to piece the story of this find back together, published and unpublished. One very helpful source of information on the subject was the Folklore Archives at the Centre d’études Acadiennes at Université de Moncton (AFCEAAC). A folklore data gathering study was conducted along the Northumberland Strait’s Acadian communities in 1976 and 1977 under the direction of Catherine Jolicoeur. This study produced an impressive corpus of local knowledge in the form of stories and legends about the treasures of Captain Kidd and other buccaneers buried along the coast. These local stories included the “treasure” found by Mr. Martin. Although a large part of the information is folkloric, one can identify some concrete data from it when it is thoroughly analysed with very specific questions and accurate quality control. Family members and descendants of Mr. Martin were also contacted and interviewed for information about the find and the story around the find. Some informant’s names are mentioned (with their permission) and some informants are anonymous.

Several museums, as well as Parks Canada collections, were consulted for the potential presence of funerary objects or archival records associated with the find. The National Archives in Ottawa were searched for material pertaining to the find. Several newspapers of the time were consulted at the Moncton Public Library (Moncton Transcripts, Moncton Times) and at the Centre d’études Acadiennes, Université de Moncton (La voix d’Évangeline). The archives folkloriques de l’Université Laval (Qc) were also consulted. The Dr. Clarence Webster Archival Funds were consulted at Mount Alison University as well as his artefact collections located at Fort-Beausejour (Parks Canada).

The location of the site required the use of historic aerial photographs and field visits. Information from three descendants of Mr. Martin (Blair Robichaud, Bernard Martin and an anonymous informant) were instrumental in determining the location.

Location of the site

No exact location of the site where the burial was found was recorded at the time of its discovery. Local historian Cyriac Daigle (1948) mentioned that Mr. Martin found the bundle on his waterfront property at Cap St-Louis. A newspaper of the time located it at “four miles below the St-Louis bridge” (Moncton Transcripts 1940). Archival research using historic aerial photos and communications with a grandson of Mr. Dominique Martin permitted us to locate the site. Mr Martin indicated to several members of his family the exact location of the find and this knowledge stayed within the family up to now.

The site is now under water at high tide due to shoreline erosion and this was taken into account in its relocation. From the sediments around the site and the actual soil type in the area it would have been a low sandy bank (Leonard 2007: 5), the same type of sandy substrate we find at other Copper Kettle Burial sites (Turnbull 1984). According to an informant the find was adjacent to a large rock that was protruding from the bank at the time in 1940. Today this rock is now surrounded by water and is at 4.08 meters from the shore (Figure 2). Knowing that the shoreline was at the rock in 1940 (81 years ago) we can evaluate the erosion rate at the site to be an average of 0.052 meter/year or 5.2 cm/year.

Figure 2

Location of the find. The shore was at the rock in 1940

Funerary Objects

Since the site was not properly registered by officials at the time, most of the funerary objects present in the bundle were lost or scattered through the family, local population, antiquarians and collectors over time. Some objects had been kept by Mr. Martin and made their way to the collection of the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton (MAUM). This is the case of the copper kettle (Figure 3), an iron adze (Figure 7) and three rusted pieces of iron (Figure 8).

Human Bones

People at that time in Cap St-Louis were very superstitious and the first reaction of Mr. Martin after the find was to bury the human remains at the end of his field behind his house (AFCEAAC 1976; D274, 81-3571 and 321-13331). According to some informants, the occupants of the house heard strange noises during the following nights and became afraid of the “ghost” of the human remains he had just found (AFCEAAC 1976; D274, 81, 3571). Under the advice of the St-Louis parish Catholic priest, Father Cajétan Poirier, the human bones found with the bundle were re-interred in the St-Louis de Kent Catholic Cemetery (MAUM 1951: 51.4.15; AFCEAAC 1976; D274, 127, 5413). Verifications with the parish of St-Louis de Kent and the Diocesan Archives at Moncton revealed no records of human bones reburied in the St-Louis Catholic Cemetery during this period. The human bones and other organic material, such as fur and birch bark, were well preserved due to the sterilizing effects of the copper salts from the kettle, as observed at several other Copper Kettle burial sites (Whithehead 1993: 23). Several informants mentioned the bad state of conservation of the bones (AFCEAAC 1976; D274, 81-3589; AFCEAAC 1977:321-13224). Apparently, a doctor (probably Dr. Webster) examined the bones but could not identify either the sex or cultural group of the remains (AFCEAAC 1976; 81-3589). Some also mentioned that there was no head or skull (AFCEAAC 1976; D274, 81, 3571) while others said the contrary (AFCEAAC 1976; D274, 127, 5413). According to the information with the copper kettle at the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton, in fact, three skulls were supposed to have been found (MAUM 1951: 51.4.15) but this latter information cannot be confirmed. Apparently Dominique Martin is said to have told one grandson that one skull was present with a long braid of black hair (Blair Robichaud 2019, pers. comm.).

The Copper Kettle

According to the Acadian Museum at Université de Moncton archives, the copper kettle was given to the museum in 1951 by Mr. Antoine Goguen, agronomist from Richibucto, NB. In fact, Mr Goguen was teaching courses at the Collège St-Joseph in Memramcook and Father Clément Cormier (President of the college) came to know about the kettle. He wrote a letter, dated February 14th, 1951, to Dominique Martin asking if he would donate it to his new Acadian Museum at the Collège St-Joseph (MAUM: 15.4.5). Mr Martin gave the kettle to Mr Goguen who brought it to the museum.

It is a rolled rim copper kettle with an iron band riveted to its rim (Figures 3 and 4). The handle is also of iron with a simple hook (Figure 5) being the same model from other burial sites (Fitzgerald et al. 1993:54). The kettle shows signs of deliberate destruction with its bottom punched in and perforated at two spots, as was the funerary custom of the time (Turgeon 1993: 14). It is a typical Basque iron-rimmed copper kettle that was manufactured and in use between 1580 and the middle of the 1600s (Turgeon 1995; MAUM, 51-4-15; Fitzgerald et al. 1993: 45; Turgeon 1998: 600). The Basque kettle was the most important trading good, in terms of quantities, of all objects and was very popular as a trade good with indigenous groups during the proto-historic period, particularly the second half of the 16th century, along the east coast (Harper 1956; Fitzgerald et al. 1993: 45; Turgeon 1998; Turgeon 2019, pers. comm.).

Figure 3

Copper Kettle found at Cap St-Louis

Figure 4

Iron rim around the kettle with a rivet viewed from the inside

Figure 5

Iron handle with hook

Physical description of the kettle

The kettle is made of copper from its greenish color and results of a tiny scratch test confirmed its reddish original copper color (Monahan 1993: 177). The diameter of the rim is 64.7cm. It has an iron band 3.5cm wide and 7.0mm thick affixed to the kettle with six iron rivets (Figure 4). Table 1 shows the distances between the six iron rivets. The average distance between rivets for five of them is 36.38cm while the sixth one is 20.5 cm. This last rivet seems to have been added this way due to wrong calculations. As shown by the hammer marks (Figure 3) the kettle was made from a sheet of copper hammered into its final form, conforming to the practice of the time (Fitzgerald et al. 1993) although this hammering pattern is different than that from other copper kettle sites from the Maritimes (Turgeon 1995 from MAUM: 51.4.5). This one appears to have been hammered out by hand as the hammer marks seem irregular. Many other kettles from burial sites have regular marks as they were probably hammered by a machine hammer (Turgeon 2019, pers. comm.).

Figure 6 shows the dimensions of the copper kettle in its upright position with its distorted form due to destruction damage. In its original form, this kettle would have been easily 30 cm (12 in) deep.

Figure 6

Dimensions of the copper kettle

Table 1

Distances between rivets holding the iron band to the copper kettle

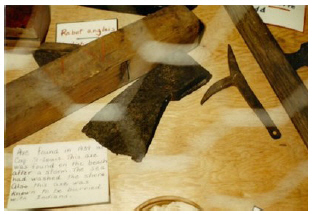

The iron adze (Herminette)

This object was not in the list made by the historian Cyriac Daigle in his book in 1948. However the iron adze was from the burial bundle as ascertained by Mr. Guy Thébeau from Rogersville. A descendant of Mr. Dominique Martin had given the object along with an axe to Mr. Camille Thébeau from Rogersville. Mr. Thébeau operated a local museum for many years but it closed in 1989. His son, Mr. Guy Thébeau, returned the axe to Mr. Martin’s descendant and transferred the adze to the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton in 1990. Small adzes were also found in Copper Kettle burials at other sites in Nova Scotia (Harper 1957: 36). This iron adze is of poor quality due to its degree of degradation by rust (Figure 7). It is 8.5 cm long by 3.5 cm wide. Its small size probably made it more appropriate for scraping hides than working wood.

Figure 7

Rusted iron adze from the burial site

Rusted pieces of iron

Three very small rusty pieces of iron were obtained at the same time as the adze in 1990 (Figure 8). Their state of degradation from rust makes it impossible to identify the original objects. The provenience of these pieces has been corroborated to the museum by Mr. Guy Thébeau, their former owner (MAUM: 1990.6a,b,c).

Figure 8

Three pieces of rusted iron found at the burial site

The iron axes

Of all thirteen axes found by Mr Martin, only one could be retraced through this investigation. Its existence was recorded in the form of photographs located in the archives of the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton. This axe was on display at Camille Thébeau’s Museum in Rogersville from the 1970s to 1989 when Mr Thébeau donated the adze to the MAUM with pictures of the objects. In 1940 William MacIntosh, Director of the Museum of St-John, informed the Moncton Transcript that “the axe is a large and heavy example of typical French axes of the 17th century (Moncton Transcript 1940). Figure 9 shows the axe at the Rogersville Museum (MAUM: 51.4.5). The actual locations of all axes, including this one, are unknown. The Basque axes are usually larger and heavier than those from the Northern Part of France, like Normandy. This one appears to be Basque like the ones found on the Klienburg cemetery site in Ontario (Turgeon 1998: 601; Turgeon 2019, pers. comm.).

Figure 9

Iron axe from the burial site on display at Camille Thébeau’s Museum in the Rogersville

Other funerary objects

Only the large Copper Kettle and the small iron adze were found at the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton during this investigation. Other objects were apparently bought by Dr. John Clarence Webster from Shediac, who was known to collect artefacts in the Maritimes, particularly Acadia (Thomas 1990: 19). He apparently bought a small kettle described by Daigle (1948) for $35.00 from Mr. Martin (AFCEAAC 1977:313-12888). Upon researching the Parks Canada collection, no traces of this kettle or its whereabouts have been found through the collection at Fort Beausejour NHS. Early in the establishment of the Fort Beausejour NHS there was a transfer of artefacts and documents to other museums and archives. The recording system of the time not being efficient, some artefacts and objects were lost during the process (Stanley 1973: 62), which seems to be the case of the small pot bought by Dr. Webster. According to one informant, who was 10 years old at the time, there were hundreds of blue and white glass beads from the find but none have been kept or found thus far. The presence of glass beads is usually good for establishing a date since each period has its distinctive bead style and color (Fitzgerald et al. 1993: 45; Turgeon 2001). Just a few beads would help to evaluate more precisely the date of the burial.

Establishing the list of funerary objects

Although no official archaeological records of the find were made public at the time, we can attempt to recreate a list of objects from archival sources and statements mentioned previously. Table 2 is a summary of objects from the find retraced through different sources. The most reliable source is Mr. Martin himself. He gave a short summary of his find during a television show filmed at St-Louis de Kent in 1961 called “La soirée Canadienne” (Martin 1961). During the three-minute interview, he mentioned that he found a large copper pot and underneath it was a chamois (tanned skin) with 13 axes, a human skeleton rolled up in fur and birch bark along with a smaller copper pot, three pot handles and many beads. (Martin 1961). Mr. Martin gave a second account of his find during a data gathering study from Université Laval in 1966 on coastal folklore along the Northumberland Strait . In this second account he mentioned again the 13 axes, the human bones with the birch bark and the “chamois” including beads and furs (Martin 1966). He also mentioned that a doctor from Shediac (probably Dr. Webster) had sent the whole kit to the Museum of St-John and it came back with a diagnostic of being “French and some 300 years old” (Martin 1966). Another reliable source is the local historian Cyriac Daigle who described the find in his book on the history of St-Louis published in 1948 as mentioned in the introduction to this article. The description of Mr. Daigle matched the ones offered later by Martin himself, although Cyriac Daigle’s description is a little more detailed than Mr. Martin’s account during his interview. Daigle (1948) mentions a sword, a knife, an iron stiletto and three pot handles that Mr. Martin didn’t mention. A bone awl of one inch by eight inches in size with five small holes of 1/16 of an inch along one edge and a criss-cross pattern sculpted in the bone was mentioned only by one newspaper article (Moncton Transcript 1940). The description given by the newspaper is of an awl with 5 small holes on one side. According to one informant, this bone awl was in his mother’s house when she was young and it was used to keep the window open when it was too hot in the summer (Robichaud 2019: pers. comm.). The location of this awl, if it still exists, is unknown. The other object mentioned only by this newspaper article was a chisel. No mention of a chisel was found in either archival or informant statements during this project and its location is unknown. Chisels or “caulking knives” were also found in other Copper Kettle Burials in the Maritimes (Whitehead 1993: 162). Another article from the same newspaper reported two weeks later on October 12, 1940 that Dr William MacIntosh, Director of the New Brunswick Museum in St-John, concluded that the ancient implements were “objects buried with the remains of an Indian Chief or a person of importance” (Moncton Transcript 1940).

Table 2

Tentative reconstruction of the list of funerary objects from different sources

Local History

The find was called “le trésor du Cap St-Louis” (the treasure of Cap St-Louis) by local people. Rumors at the time were that Mr Martin found gold or silver along with the funerary objects but this assumption was never proven (Daigle 1948: 163). Apparently the find created some stir and attracted many visitors (Daigle 1948: 163).

From the reality of the find to the rich imagination of local residents, the legend of the “Treasure of Cap St-Louis” was born (Dupont 1977: 131). The story is part of a book on the hidden treasures of Québec and Acadia (Dupont 1999: 138-140) and another one on the “Filibusters of Acadia” (Robichaud 2008).

The Centre d’études Acadiennes (CEA) conducted a regional folklore study in 1976 and 1977 collecting information about stories of treasure along eastern New Brunswick coastal communities (AFCEAAC 1976; AFCEAAC 1977). They collected several statements from interviews with people of the area saying that Dominique Martin had found silver or gold in the “Treasure” and after that he bought a car and was wealthy (AFCEAAC 1977). This is part of the folklore and no evidence of finding money or gold was ever brought forward. Descendants of Mr. Martin confirmed that there were no grounds to believe their grandfather had found any money or gold in the process. He was a hardworking man with modest means as shown by his house in figure 10.

Figure 10

House of Dominique Martin at Cap St-Louis in 1970

The archaeological evidence of this find supports the conclusion of a Mi’gmaq Copper kettle Burial from the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th centuries more than a treasure. From all the Copper Kettle Burials found in the Maritimes and Ontario, none contained either silver or gold (Fitzgerald et al. 1993; Whitehead 1993; Turgeon 1997; Turgeon 2019, pers. comm.).

Some objects are believed to be still kept in private collections in the area. However, none were relocated during this research. Hopefully such objects might potentially resurface in the future and could be properly taken care of in a controlled museum environment and their study would enrich our historical knowledge of this protohistoric period.

Conclusion

From evidence collected during this investigation and knowledge from the literature, it is clear that what Mr. Martin found in September 1940 was an Indigenous Copper Kettle Burial, typical of those found at several sites in the Maritimes, the St-Lawrence River and up to the lower Great Lakes (Fitzgerald 1993: 47; Turgeon 1993: 8; Delmas 2016: 93). This burial is probably Mi’gmaq since it was located in the heart of their traditional territory. These types of burials were in practice from the beginning of the contact period (1560’s) until around the middle of the 17th century (Turgeon 1997:8). The copper kettle was not the only object of trade at the time. Knives, axes, swords and other “iron goods” were common in Basque cargo of the period (Turgeon 1997:8). The Basques were known to be present in Gaspé during the second half of the 16th century (Turgeon 2019) and in the Baie des Chaleurs during the 17th century (Loewen and Goya 2014) and it would have been easy for a group of Mi’gmaq from the area of Cap St-Louis to obtain European goods through trade or even direct contact. The banded copper kettle, like the one found at Cap St-Louis, was a primary commodity in the Basque trade (Fitzgerald et. al. 1993:47).

The earliest Copper Kettle Burial contained a mix of aboriginal stone, bone and wood implements (bow, arrows, stone knives) along with some iron trade goods from the Basques (axes, knives, swords). The latest burial during this period had less aboriginal goods, such as stone and bone implements, and more European pottery and iron objects particularly muskets or parts of muskets (Whitehead 1993: 86). Although just a few objects were retraced during this project, enough information from several sources has been gathered to permit the reconstruction of a tentative list of funerary objects present in the burial.

Delmas (2016: 91) identified four approximate phases in the evolution of the funerary material culture for the Northeast region. This Copper Kettle burial seems to correspond to Phase 3 (1580-1600) of this period. The burial found at Cap St-Louis, a mix of a few aboriginal goods (furs, birch bark, bone awl) where the majority of the objects are blue and white glass beads, iron goods and a Basque copper kettle, is more likely associated with the early period (late 1500’s or early 1600’s) rather than the later part of the 1600’s. The Basque kettle disappeared from the archaeological records of northeastern North America by the 1630’s (Fiztgerald et.al. 1993:55; Turgeon 2019: com. pers.). As mentioned earlier, a few beads from the find would greatly help pinpoint the date of the burial.

As a result of this investigation the site has been allocated a provenience number by Parks Canada. It is now site number 9E82 and is offered protection under the National Parks Act. There is no doubt that some objects are still in the possession of private collectors keeping them as heirlooms or souvenirs of a past era. The resurfacing of these objects from private collections would greatly help to provide a better picture and knowledge of what was in this burial and increase our knowledge of Mi’gmaq burial practices.

In the spirit of reconciliation Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn (MTI), representing nine Mi’gmaq communities in New Brunswick, and the Université de Moncton have created a “Rematriation Committee” named Mi’kmaq and Université de Moncton Mawiomi on Truth and Reconciliation (in French: Mawiomi Mi’kmaq et Université de Moncton sur la verité et la reconciliation) and agreed that all funerary objects in the University’s Museum will be returned to the Mi’gmaq of New Brunswick (Cloud 2020). The term “rematriation” given the committee is to note the matriarcal nature of the Mi’gmag people. The return of these funerary objects to their rightful owners will be the first step to a meaningful truth and reconciliation of the academic institution and the Mi’gmaq of New Brunswick.

Appendices

Note

-

[1]

This investigation would not have been possible without the assistance of several individuals and organizations. First and foremost, I want to thank Charles Burke for initiating the idea of investigating this unrecorded find. I would like to thank the following people for their help during this project: Stacey Girling-Christie at the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa; Jennifer Longon, Christine Little, Mary Kuna and Dr Peter Laroque from the NB Museum in St-John; Robert Richard from the Centre d’Études Acadiennes de l’Université de Moncton; Christine Thériault from the Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton; Laurence Boutet de l’Université Laval; Madame Émerise Martin from St-Louis for reaching deep into her memories of the time; Blair Robichaud for generously sharing his family knowledge and stories about the find made by his grandfather, Mr. Martin; Guy Thébeau from Rogersville for information about some objects; Maurice Robichaud for sharing his knowledge about the find; Juliette Bulmer from Parks Canada for searching the Webster Collection at the Fort Beausejour NHS and Sara Beanlands from Parks Canada Dartmouth Conservation Laboratory. Many thanks to Laurier Turgeon from Université Laval for an early review of this report and sharing his considerable knowledge on the presence of the Basques in the Maritimes. Thanks to Kevin Leonard for sharing his knowledge about the find. Thanks to Katrina Sock for reviewing the manuscript. Thanks to Donna Augustine for reviewing and making valuable suggestions to improve its quality and thoroughness. I also want to thank some anonymous informants, as their information was very valuable. Last but not least, for all the local contacts, data and histories he collected and recorded during this investigation, I would like to sincerely thank Bernard Martin, without whom this report would not exist. This article has been written with the permission of Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn (MTI) and Parks Canada.

References

- AFCEAAC. 1976. Archives de folklore du Centre d’études acadiennes Anselme-Chiasson, collection Catherine-Jolicoeur, 142-A, Les trésors cachés. (81-3571: Léo Martin), (Philomène Gallant:127-5413), Jos Poirier:81-3589), (Conrad Doucette:321-13331).

- AFCEAAC. 1977. Archives de folklore du Centre d’études acadiennes Anselme-Chiasson, collection Catherine-Jolicoeur, 142-A, Les trésors cachés. (Antoine Comeau:321-13224), (Antoine Gallant:313-12888).

- Daigle, Cyriac. 1948. Histoire de St-Louis de Kent: Cent cinquante ans de vie paroissiale en Acadie nouvelle. L’Imprimerie Acadienne Limitée, Moncton.

- Cloud, Tracy Ann. 2020. Mi’gmawe’l Tplu’taqnn (MTI). Personal communications in January 2020.

- Degrâce, Eloi. 1984. “Chaudrons de cuivre et sépultures micmaques.” Revue d’histoire de la Société Historique Nicolas Deny 12(2): 41-45.

- Delmas, Vincent. 2016. “Beads and trade routes: Tracing sixteenth-century beads around the Gulf and into the Saint Lawrence Valley.” In Brad Loewen and Claude Chapdelaine (eds.), Contact in the 16th century: Networks among Fishers, Foragers and Farmers: 77-115. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of History and University of Ottawa Press, Mercury Series, Archaeological Paper 176.

- Denys, Nicola. 1908 [1672]. The description and natural history of the coasts of North America (Acadia). Translated and edited by W.F. Ganong. Toronto: The Champlain Society.

- ECCC. 2009. Environment Canada and Climate Change: Historic database on storm impacts summaries. http://www.ec.gc.ca/hurricane/default.asp?lang=En&n=F164E429-1

- Erskine, J.S. 1959. “Their crowded hour: The Micmac cycle.” The Dalhousie Review 138: 443-452.

- Fiztgerald, William and Peter Ramsden. 1988. “Copper based metal testing as an aid to understand early European-Amerindian interactions: Scratching the surface.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 12: 153-161.

- Fitzgerald, William, Laurier Turgeon, Ruth Whitehead and James Bradley. 1993. “Late Sixteenth Century Basque Banded Copper Kettles.” Historical Archaeology 27 (1):44-57.

- Harper, Russell. 1956. Portland Point: Crossroad of New Brunswick History. St-John: The New Brunswick Museum.

- Harper, Russell. 1957. “Two seventeenth century Micmac ‘Copper Kettle’ burials.” Anthropologica 4: 11-36.

- Hyrnick, Gabriel, Jesse Webb, Christopher Shaw and Taylor Testa. 2017. “Late maritime woodland to protohistoric culture change and continuity at the Devil’s head site, Calais, Maine.” Archaeology of Eastern North America 48: 85-108.

- Kain, Samuel and Charles Rowe. 1903. “Some relics of the early French period in New Brunswick.” New Brunswick Natural Society Bulletin 19: 302-312.

- Leonard, Kevin. 2007. Preliminary report on archaeological test excavations at Cap St-Louis containment cell and parking lot: Kouchibouguac National Park. Contract Report for Parks Canada, Archaeoconsulting, NB.

- Loewen, Brad and Miren Goya. 2014. “Le routier de Piarres Detcheverry, 1677. Un aperçu de la présence basque dans la Baie des Chaleurs au XVIIe siècle.” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 68: 125-151

- Martin, Diminique. 1961. Témoignage de Dominique Martin sur le trésor trouvé. Émission La soirée Canadienne, St-Louis de Kent.

- Martin, Diminique. 1966. L’histoire d’un trésor cache. Archives folkloriques de l’Université Laval. Collection Jean-Claude Dupont, enr. 529.

- MAUM. Musée Acadien de l’Université de Moncton. Museum files 51.4.15 and 1991.56 (a,b,c,d).

- Monahan, Valery. 1993. “Scratch-testing of the trade pots from Pictou site, BkCp-1.” Appendix to Whitehead, R.H., 1993, Nova Scotia proto-historic period 1500-1630, Curatorial Report Number 75. Department of Education, Nova Scotia, pp: 175-180.

- Moncton Transcript. 1940. “Find ancient objects after a big storm.” Edition of September, 19, 1940. Page 3. Archives, Moncton Public Library.

- Moncton Transcript. 1940. ”History of relics determined.” Edition of October 12, 1940, page 3. Archives, Moncton Public Library

- Moreau, Jean-François. 1998. “Traditions and cultural transformations: European copper-based kettles and Jesuit rings from 17th century amerindian sites.” North American Archaeologist 19: 1-11.

- Mousette, Marcel. 2009. “A universe under strain: American nations in north-eastern North America in the 16th century.” Post Medieval Archaeology 43: 30-47.

- Petersen, James, Malinda Blustain and James Bradley. 2004. “‘Mawooshen’ Revisited: Two native American contact period sites on the central Maine coast.” Archaeology of Eastern North America 32: 1-71.

- Robichaud, Armand. 2008. Les flibustiers de l’Acadie, coureurs des mers. Les Éditions de la Francophonie.

- Robichaud, Blair. 2019. Grandson of Dominique Martin. Personal Communications.

- Starr, Frederick, 1888. “Preservation by copper salts.” The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal 10: 279.

- Stanley, George. 1973. “John Clarence Webster, the Laird of Shediac.” Acadiensis 3: 51-71.

- Thomas, Gerald. 1990. John Clarence Webster: the evolution and motivation of an historian 1922-1950. Masters Thesis, Department of History, University of New Brunswick.

- Turgeon, Laurier. 1997. “The tale of the kettle: Odyssey of an intercultural object.” Ethnohistory 44: 1-29.

- Turgeon, Laurier. 1998. “French fishers, fur traders and Amerindians during the sixteenth century: History and archaeology.” William and Mary Quarterly 55(4): 585-610.

- Turgeon, Laurier. 2001. “French beads in France and Northeastern North America during the sixteenth century.” Historical Archaeology, 35: 58-82.

- Turgeon, Laurier. 2019. Une histoire de la Nouvelle-France: Français et Amérindiens au XVIesiècle. Paris: Belin.

- Turnbull, Christopher. 1984. The Richibucto burial site (CeDf:18), New Brunswick Research in 1981. New Brunswick Cultural and Historical Resources. Manuscripts Archaeology 2, Fredericton.

- Whitehead, Ruth. 1993. Nova Scotia: The proto-historic period 1500-1630, Curatorial Report No.75. Halifax: Department of Education, Nova Scotia Museum.

- Whitehead, Ruth, L.A. Pavlish, R.M. Farquhar and R.G.B Hancock. 1998. “Analysis of copper based metals from three Mi’kmaq sites in Nova Scotia.” North American Archaeologist 19: 279-292.

List of figures

Figure 1

Mr. Dominique Martin with some of the funerary objects recovered after a storm in 1940, Cap-St-Louis

Figure 2

Location of the find. The shore was at the rock in 1940

Figure 3

Copper Kettle found at Cap St-Louis

Figure 4

Iron rim around the kettle with a rivet viewed from the inside

Figure 5

Iron handle with hook

Figure 6

Dimensions of the copper kettle

Figure 7

Rusted iron adze from the burial site

Figure 8

Three pieces of rusted iron found at the burial site

Figure 9

Iron axe from the burial site on display at Camille Thébeau’s Museum in the Rogersville

Figure 10

House of Dominique Martin at Cap St-Louis in 1970

List of tables

Table 1

Distances between rivets holding the iron band to the copper kettle

Table 2

Tentative reconstruction of the list of funerary objects from different sources

10.7202/1032022ar

10.7202/1032022ar