Abstracts

Abstract

The problem with many archives is that they are searchable only by supplementary metadata (anecdotal data not provided by the original source), rather than secondary metadata (descriptive information that covers dates, origin, history, and cross-referencing); information about a visual object is not always reliable, especially when it comes to Black Canadians. Supplementary metadata in Canadian archives are not classified by race or ethnicity, thus, the very structure of the archive erases from public memory the lived experiences of Black Canadians. Given the move toward digitization over the last fifteen years, the importance of the archive has become a topic of discussion. Since the public can now search through on-line collections, the need to protect and promote material archives has never been more important. This paper will explore the question of the archive-as-subject, rather than archive-as-source, through storytelling. Storytelling is one of the many cultural expressions that have connected Black populations. Using first-person narrative, I give examples from my ten-year-long experience working in Black Canadian archives to probe how the archive can move from its depository role to become a site where memories about Black Canadian experiences across time, space, and place are curated and narrated. What are the ethical challenges around this kind of reform?

Résumé

La recherche dans plusieurs archives est problématique du fait qu’elle est tributaire de métadonnées complémentaires (dont des anecdotes ne provenant pas de sources originelles), plutôt que de métadonnées secondaires (dont l’information descriptive comprenant les dates, l’origine, l’histoire et le croisement de références). L’information accompagnant les objets visuels n’est pas nécessairement fiable, d’autant plus que la race et l’ethnicité sont souvent omises dans leur description. Or, celles-ci sont des marqueurs socio-historiques essentiels de la présence des Noirs au Canada. Ainsi, la structure même des archives efface les expériences vécues des Noirs de la mémoire publique canadienne. Considérant la numérisation croissante des quinze dernières années, la facilité du public à identifier ce qu’il cherche dans les collections en ligne rend d’autant plus urgente la question de la recherche dans les archives. Cet essai explore la question des « archives-en-tant-que-sujet », plutôt que des « archives-en-tant-que-source », par la narration; une forme d’expression culturelle commune aux communautés noires. J’y raconte mes dix ans d’expériences dans les archives dédiées aux Noirs au Canada, en évaluant comment les archives peuvent dépasser leur mission d’entreposage et devenir un site où la mémoire des Noirs à travers le temps, l’espace et le lieu est conservée et surtout racontée. Quels sont les défis éthiques d’une telle réforme?

Article body

Introduction

There is no definitive national Black archive in Canada to preserve, promote, and protect the historical books, documents, and artefacts of Black Canadians. Instead, Canada’s Black archive comprises disparate collections, spread across the country, that aim to preserve the histories of African Canadians who live(d) in specific provinces and/or cities and/or towns.[1] By contrast, national Black archives exist in other parts of the world. In the Netherlands, for instance, there is a historical archive managed by the New Urban Collective (NUC), which is a network of students and young professionals with the mission to empower young people with ethnic minority backgrounds, in particular those of African descent (Esajas and de Abreu, 2019). It holds a unique collection of books, documents, and artefacts, which are the legacy of Black Dutch writers, scientists, and activists, and it also documents the history of Black emancipation movements and individuals in the Netherlands (Esajas and de Abreu, 2019). The archive’s aim is to “inspire conversations, activities and literature from black and other perspectives that are often overlooked elsewhere, and to make black Dutch history accessible to a wide audience” (Esajas and de Abreu, 2019, p. 404). In the absence of such an archive in Canada, there have been inquiries into Black collections across the country, which inform this article.

As founder of Northside Hip Hop Archives, a digital platform that documents Canadian hip-hop history and culture, Mark Campbell observes that “archives of hip hop culture today are both virtual and physical spaces that collect and accumulate items of material culture and (re)locate them most often within a university context, whose public accessibility can be questionable” (Campbell, 2018, p. 76). The problem of accessibility extends to other archives in Canada. For example, Seika Boye, who worked at Dance Collection Danse (DCD) Archives, explains that until 2013, DCD was located in a relatively small row of houses in the St. Lawrence district of Toronto and inside the home of its cofounders, Mariam Adams and her late husband Lawrence Adams (Boye, 2013, p. 17). While there were archives housed in every available corner, with artifacts, paintings, and kitsch decorating on all of the walls, a photograph of a nameless Black woman hung behind Mariam and Lawrence’s desk. This photograph was the catalyst for Boye’s observation that “The mystery woman’s blackness … highlights the lack of accessible material about African-Canadian amateur and professional performance during this era available for reference” (Boye, 2013, p. 18).

With these conversations in mind, this article focuses on the question of how Black women appear in Canadian visual archives, and on the issue of their namelessness. Some of the myths that surround the archive are “that it is unmediated, that objects located there might mean something outside the framing of the archival impetus itself,” and “that the archive resists change, corruptibility, and political manipulation” (Taylor, 2003, p. 19). If “what makes an object archival is the process whereby it is selected, classified, and presented for analysis” (Taylor, 2003, p. 19), what can be said about Black women in Canada’s archival record? What recourse do researchers in Black Canadian archives have if individual things mysteriously appear in or are absent from the archive? What are the ethical challenges of recovering Black Canada in the archive? And what are the possibilities for a Black Canadian national archive?

A Brief Literature Review of The Black Archive

The archive is not considered as an inert repository for historical information (Stoler 2002)—a neutral, benign, transparent record, whose meaning is stable, definitive, and static—but is aligned with dynamic, fluid processes of knowledge-production, -systems, and -formations (Farber, 2015, p. 2). The United States (US) represents the most exemplar case of multiple Black archives that all aim to accumulate information, documents, data, and memories of Black people coupled with artifacts that reflect subjectivities, identities, and knowledge production. Since 1905, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library, has held manuscripts, archives, and rare books that are available to the public and which document the history and culture of people of African descent not only in America but also across the Americas and Caribbean. In 1974, the Black Archives of Mid-America (BAMA) in Kansas City, Missouri, has collected, preserved, and made available to the public materials documenting the social, economic, political, and cultural histories of African Americans in the central United States. In an interview with American Visions, Horace Peterson III, founder and executive director of BAMA, said, “We want to bring black information into the twenty-first century. We want to have a process at work that will allow us to collect information about our people, preserve it and make it accessible to all Americans” (Helms-Mindell, 1989, p. 56). Similarly, when the Black Archives Research Center and Museum (known as “The Black Archives”) opened on the campus of Florida A&M University in Tallahassee in 1976, the archive was not aimed solely at academics; instead, there was a belief that Black history was in danger of being forgotten not solely by the dominant culture but by Black people. “It must be dug for, and a tradition for preserving it must be established,” said James Eaton, director of the archive, in an interview (Ashdown, 1979, p. 48). All of these efforts culminated in the building of The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) located in Washington, DC, which opened in 2016. NMAAHC, part of the Smithsonian Institution, is located on the National Mall, and is devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture.

There are very few scholars in Canada who work with Black archival collections, specifically image archives. Similar to the US collections, Black archival collections in Canada document the lived experiences of Black Canadians and communities; in some cases, the documents are labelled “Black history” because of subject matter and/or because they are connected to Black communities and/or experiences. In other instance, these archival collections are not “archives” in the sense of comprising “a range of multi-faceted, nuanced, differentiated yet potentially interconnected definitions, conceptualisations and meanings, within each of which alliances and connectivities may be discerned” (Farber, 2015, p. 2), but would more aptly be described as “evidences.” Stated otherwise, there is often no way to connect artifacts and/or images in a Black collection in one location with other artifacts and/or images in another location because many are not cross-referenced or annotated. That said, there are two kinds of archival collections with Black Canadian records—image-based (photographs, ephemera, lithographs, prints, etc.) and textual (newspapers, magazines, documents, personal records, etc.). This article is primarily focused on image-based archival records because these are the most difficult to access, owing to a paucity of searchable images and/or to missing and/or incomplete catalogue labelling. While the problem of inadequate archival indexing for Black archives is experienced on an interpersonal level (i.e., encounters with archival matters stored in unsorted manila envelopes and/or cardboard boxes with “stuff” and staff lacking expertise to discuss collection contents), the real issue is structural. Around the world, Black communities have found ways to circumvent structural barriers towards the aim of establishing a national Black archive.

For example, in the United Kingdom (UK), the Black Cultural Archive (BCA), founded in 1981, is the only national heritage centre dedicated to collecting, preserving, and celebrating the histories of African and Caribbean people in Britain. Len Garrison, founding member of the BCA, once said:

The Black Cultural Archives would hope to play a part in improving the image and self-image of people of African and African-Caribbean descent by seeking to establish continuity and a positive reference point ….. Advancing this scheme within an educational context, outside a university setting, is a development that would bring primary sources of archaeological, historical and contemporary materials within reach of both Black and white communities. It would also provide a basis for recording the social and cultural history of African and Afro-Caribbean people in Britain”

Garrison, 1994, p. 238

At the same time, over the last two decades, informal and independent archives have substantially grown in the UK. Some of the reasons for this growth include an increased awareness of the absences and challenges to dominant heritage narratives; the continued impact of migration within the UK, as well as international movements in stimulating interest in place and belonging; the formation of virtual communities; and the ability of geographically distributed individuals to focus on and collaborate around the heritage of a shared identification or a specific geographical location (Flinn, Stevens, Shepherd, 2009, p. 74). While these collections are often held by community archives (similar to those in Canada) that include created as well accumulated materials frequently found in museums such as books, ephemera, documents, photographs, and audio-visual materials, some are located in a physical space, a virtual archive, or some hybrid of the two (Flinn, Stevens, Shepherd, 2009, p. 74). Nevertheless, the term “archives” has been used to describe these collections to convey “a sense of the historical significance and treasured nature in which these materials are held by those responsible for their collection which perhaps the terms library or even museum might not” (Flinn, Stevens, Shepherd, 2009, p. 74). For a similar reason, the term “archive” is appropriate to use to describe Black Canadian collections though some collections—especially those small in size—might not be categorized as an archive.

The lack of a national Black Canadian archive creates two ethical challenges. First, how can the archive move from its depository role to become a site where memories about Black Canadian experiences across time, space, and place are curated and narrated, where they are searchable and have cross-references to other archival collections? Second, if we are to shift the archival logic, what would this kind of reform look like? Over the last decade, the archive has become an increasing area of interest for academics, especially in the field of Canadian history where, historically, Black Canadians have been written out, erased, and ignored. Cecil Foster’s most recent book, They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada (2019), was written largely because of first-hand accounts Foster was able to gather from railway “Pullman” porters who were still alive, and, in addition to their stories, he made use of archival materials. My first book could not have been written without image, newspaper, and manuscript archives (Thompson, 2019).

Despite these successes, however, doing-archival-work-while-Black means you have to refuse to take “No” for an answer when you hit the proverbial denial of even having Black collections in the first place. There were many instances between 2010 and 2016 when I was conducting research for my book where I purposefully had to scour online collections with detailed cataloguing information before attending an archive because I knew I would interact with people who would tell me either that they were not sure whether they had any collections or, most often, that what they had “probably would not be of much use” because it was only a few artefacts. These responses point to an institutional problem rather than to the actions of individuals. Stated otherwise, invariably, the impetus behind the conscious decision to “constitute” the archive (as opposed to a collection of materials that were produced as part of another activity) is in part a reaction to the lack of representation and visibility of the community concerned within the dominant culture and formal heritage organizations (Hall, 2001, p. 89). Additionally, once the archive is formed, it is a discursive formation in that “since the materials of an archive consist of a heterogeneity of topics and texts, of subjects and themes, what governs it as a ‘formation’ is not easy to define. The temptation would be to group together only those things which seemed to be ‘the same’” (Hall, 2001, p. 90). Hence, Black collections are often filled with some images and/or textual records that “connect” but some that do not. This article makes the claim that there is a need to rethink the act of restoring, maintaining, and cataloguing Black Canada in order to bring diverse histories into the present and future.

Historically, Black communities have not had control over their histories, the places and spaces of their communities, and the manner in which narratives of belonging and dis-belonging to the nation are catalogued within the archive. In this regard, Saidiya Hartman makes several observations about belongingness and Blackness. “The significance of becoming or belonging together in terms other than those defined by one’s status as property, will-less object, and the not-quite-human should not be underestimated,” she writes, adding, “This belonging together endeavors to redress and nurture the broken body; it is a becoming together dedicated to establishing other terms of sociality, however transient that offer a small measure of relief from the debasements constitutive of one’s condition” (Hartman, 1997, p. 61). The main thrust of Hartman’s argument is that rather than clinging to an idea of community as homogenous or to a sameness of experience, when we grapple with the differences that constitute community, we are then able to understand “a range of differences and create fleeting and transient lines of connection across those differences” (Hartman, 1997, p. 61). Rethinking the Black Canadian archive will achieve a similar goal. Rather than thinking of Blackness in Canada through a lens of sameness or of Blackness as representing “what Canada is not” (Walcott, 2003, p. 120), I argue that the archive is the site, source, and subject through which we can complicate and carve out space for articulating the complexities of Blackness in Canada, historically and in the present. In the UK, the interrelationship between absences and marginalizations in public heritage and national narratives, and absences and marginalizations in the archival record are recognized as complex but also extremely significant and something that community archives often address directly in their work (Schwartz and Cook 2002, pp. 2–3, 7–9). What would the interrelationship between absences and marginalizations look like in the Canadian archival record?

Rethinking Canada’s Colonial Archive

Across Canada, archival collections tend to be filled with documents related to, and from, the perspective of the upper echelon of European settlers to Canada; histories of communities are built using archival records and tend to focus on the impact of the white settlers, with other stories being briefly mentioned, if at all (Weymark, 2017). The issue of colonial archives is one that has not received much critical inquiry in Canada. In treating colonialism as a living history that informs and shapes the present rather than as a finished past, a new generation of scholars are taking up Michel de Certeau’s invitation to “prowl” new terrain as they re-imagine what sorts of situated knowledge have produced both colonial sources and their own respective locations in the “historiographic operation” (Stoler, 2002, p. 89).

In Namibia, for instance, a southern African nation that was colonized by Germany between 1884 and 1915, new questions are being asked about the colonial structure that dictates how Namibians locate themselves in the archival record. Under German colonial rule, a European system of recordkeeping was introduced at all levels; when the National Archives of Namibia (NAN) was established in 1939, it initially secured surviving German records and later continued to archive civil administration as well as judicial records from the period under South African rule (1915–1990), but in 1990 the country transitioned from being a South African colony to being an independent nation (Namhila, 2016, p. 112). Yet about 95 percent of the total collections at the NAN are archives of German and South African colonial administrations, not of Indigenous (Black) Namibians (Namhila, 2016, p. 112). While colonial archives have been defined as “as both archival records and archival institutions that were created and maintained under colonial rule, that is, in the political context of a territory that is not sovereign but ruled by another country in a colonial situation” (Namhila, 2016, p. 114) and as “legal repositories of knowledge and official repositories of policy” (Echevarría, 1990, p. 30–31), Canada is a colonial nation once controlled by the French and British, but we tend not to frame our archival collections as colonial depositories. Instead, our national library, Library and Archives Canada, calls itself “the custodian of our distant past and recent history.” This vague descriptor negates Canada’s history of slavery, colonization of Indigenous lands, and “the mundane issue of how these exclusions and configurations of power have shaped simple but vitally important issues, such as the availability of vital documents to ordinary citizens” (Namhila, 2016, p. 115).

The ethical challenge arises when Eurocentric collection practices such as privileging white settler ancestry, official employment, and immigrant records, which remain standard in the field, impinges upon the breadth and scope of the archive. Stated otherwise, because archives have historically told, preserved, and celebrated the lives, stories, and communities of white European settlers to Canada, if these same practices are not challenged, questioned, and pushed to go beyond what is considered “standard practice,” that ultimately impacts the ability of archives to tell more diverse stories, and to reflect the changing demographics of communities across the country. Just because the research is more challenging, that does not mean that we should not undertake it (Weymark, 2017). Some of the questions that surround deconstructing the archive include asking, Why was this item placed here? Is there a larger significance or context that is missing? What does it mean that these items were preserved within the archive? Framing the archive as a form of history as narrative has elevated the archive to new theoretical status, with enough cachet to warrant distinct billing—the archive is now worthy of scrutiny on its own (Stoler, 2002, p. 92). Once an archive is compiled, it makes a claim on history; as a vehicle of memory, it becomes the trace on which a historical record is founded, and it makes some people, things, ideas, and events visible, while relegating others, through its signifying absence, to invisibility (Smith, 2004, p. 8). When we begin to think of the archive as subject, it means that we begin to interrogate its structure, its framing, and its contents as being part of the process of the archive, not merely taking archives as they are presented—as a “source” where we go to “find” what we are looking for when it comes to a research project.

Complicating the narrative, shifting to archive as subject, and incorporating storytelling into the archival memory are definitive steps that can be taken by archivists, academics, and concerned citizens to address the ethical dilemma of how to reform the archive so that it shifts from its depository function to an active historical agent. Storytelling, for instance, is a cultural expression shared by African-descended people throughout the Americas; dub-poets across the Black diaspora are an example of the continued the legacy of the African griot, a West African storyteller, singer, musician, and oral historian. In the UK, the BCA was the result of Garrison’s work with the African and Caribbean Educational Resource Centre in the 1970s and his observations about the lack of teaching of Black history in London schools and the alienating effect it was having on Black children. This eventually led him and a group of similarly concerned parents and activists to found the African People’s Historical Movement Foundation in 1981, which then led to the BCA (Flinn, Stevens, Shepherd, 2009, 78). It did not happen because of change within archival practices and institutions. Instead, community and collective memories related at some level to an awareness and sharing of a history that drew upon a range of sources (including traditional documentary records as well storytelling and shared community knowledge) for its authority, authenticity and validity within the audience that received it (Flinn, Stevens, Shepherd, 2009, 76). This is the context that shapes how I engage with Black Canada’s archives, and which surrounds the issue of unnamed Black women.

Unnamed Black Women and Archival Memory

My foray into Black Canadian archival work began when I was a PhD student at McGill University. While there was no stand-alone, dedicated archive of Black Canadian (and/or African Canadian) women,[2] for three months in 2012, I examined image records (the Notman photographic archive and the paintings, prints, and drawings collections) at the McCord Museum in Montreal. I wanted to collect materials that would illustrate (visually) how (and where) blackface minstrelsy was performed in the city, the use of humour, and how its underlying pathos was mobilized by the performance of racial stereotypes. I also sought to find material evidence that would show how Black women’s bodies were caricatured in minstrelsy—that is, the misrepresentation of their bodies, hair, and skin colour. Reflecting on the work that I did during my doctoral studies, I believe there is an ethical dilemma that archives with Black Canadian holdings have to begin to address—namely, Black women as unnamed subjects. It is important to note that there are examples of unnamed white women in the Canadian historical record; however, for example, when one uses the keywords “Photography” and “Portrait; female” to search the 20 494 photographs searchable through the McCord Museum’s online database, dozens of photographs of unnamed white women are retrieved, but, given the scope of the collection, such absences are reasonable and expected. The comparative figure for images of Black women held by the McCord is six, two of those images are of the same person, and the remaining four are of unnamed Black women. Their unnaming seems less reasonable and is unexpected. With regard to Black men, I have located seven images in the McCord’s collection, the most notable being that of John Anderson, a fugitive African American who, in the fall of 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, was involved in extradition proceedings that focused on the fact that he had killed a white man during his escape from slavery (Johnson, 1999, 55). Anderson’s McCord image is dated 1861, which means it was undoubtedly taken after he was set free in Toronto on February 16 of that year.[3] In Mrs. McWill and Mrs. Ringold’s servants, St. Alban’s, Vermont, 1873, two Black men sit atop a storage box and, like Black women servants in the collection, they are also unnamed.[4] While the McCord is my primary case study, in my experience in Black archival collections across the country, this issue is widespread. Karina Vernon’s work on the Black prairie archive aims to fill in the historical gaps in Western Canada’s Black archival memory.[5]

For example, a photograph of a Black nanny with her white charges in Guysborough, Nova Scotia, taken around 1900 is held as part of the Buckley Family fonds at the Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management (NSARM) in Halifax.[6] The photograph, attributed to William H. Buckley, is most often used to depict Black women in early twentieth-century Canada.[7] The Buckley family fonds (1889-1952) is a collection that commemorates William Hall Buckley (1874–1950), who, according to the archival description at the NSARM, was born at Guysborough, and was the son of James Buckley, merchant, and his wife Mary (Scott). Additionally, William Buckley had nine children, three of whom, Mary Abigail, Edith Willena, and Walter Guy, participated with their father to some degree in a photography business out of their jewellery store. A variation on this photography business existed until 1952. Given the extensive knowledge of the Buckley family and their photographic business, why is this Black woman, under the family’s employ, still nameless in their fonds since the image itself was taken by the family? Who was this woman? Was she also born and raised in Guysborough? Or was she a domestic who came to Canada for the specific purpose of caring for white families and their children? How long did she work for the Buckley family, and how many of their children did she care for? These questions remain unanswerable because the archive has not asked us to even think about these questions as it relates to this unnamed Black woman.

Such examples pose an ethical question: is it the responsibility of the archive to “name” all its subjects, or does the user of the archive have a role to play in investigating such contents? In my opinion, while the archive cannot (and should not) answer all questions and provide all answers, if the stumbling block to finding Black collections is primarily the lack of identifiable information, the archive has a significant role to play in creating a roadmap for researchers to follow. For example, in 1963, a recently founded American dance company toured Brazil for the first time, leaving behind a dossier of materials concerning the drums, dances, and rituals of Afro-Brazilian religion, the commodification of samba, and a play about the iconic maroon figure in Brazil, Zumbi; the company was the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, founded in New York City in 1958 by choreographer and dancer Alvin Ailey (Kabir and Negro, 2019, p. 6). The dossier of the Brazil tour is preserved as Series 18 in Box 33 of The Allan Gray Family Personal Papers of Alvin Ailey, housed within the BAMA in Kansas City (Kabir and Negro, 2019, p. 6). If these records were unnamed, someone accessing this collection might not intuit their importance because “studies of Alvin Ailey’s work are almost completely silent on the Ailey Company’s Brazil tour of 1963” (Kabir and Negro, 2019, p. 7).

Another example of an unnamed Black woman in the archive can be found at the Archives of Ontario (AO) as part of the Alvin D. McCurdy fonds. Alvin D. McCurdy, an African Canadian born in 1916 in Amherstburg, Ontario, was involved with antidiscrimination groups such as the Amherstburg Community Club and the Amherstburg Progressive Association of Coloured People. He was also a historian, genealogist, and collector of Black history material, and, during his lifetime, he amassed dozens of newspaper clippings and postcards relating to southern Ontario and the northern US, as well as a variety of textual records, such as minutes, research files, scrapbooks, and correspondence. He also collected approximately 3 000 photographs of church activities, social and cultural events, and friends and family members (Archives of Ontario). When McCurdy passed away in 1989, the AO purchased his records and, while they are an invaluable resource, I still find it problematic that four Black women, even within the fonds of an African Canadian archive, remain unnamed.[8] Given the genealogy of the fonds themselves, it is surprising that the women in these photographs remain unidentified. In Woman Holding a Child, c. 1900–1920, for instance, a seated Black woman holds a child in both hands as she warmly gazes into the camera.[9] It represents a rare glimpse of a Black woman as loving nurturer to her own children, not to a child in her employ—implied in the image based on her dress (not a uniform) and proximity to the child (both physically and phenotypically). As she is unnamed, her presence in the archive is made even more precarious. There are ten images of Black women in the Alvin McCurdy fonds who are named, such as Ella Mae Adams and Reverend Mary Scott Lyons;[10] however, because there is no archival description for these women, they remain equally unidentifiable in terms of their position in the community, genealogical connection to McCurdy, if any, and their links to Amherstburg. It should be noted, however, that the NSARM and the AO are two of the only provincial archives in the country that have culled their African Canadian (African Nova Scotian and African Ontarian) collections to form a defined category searchable via the virtual database.

Identification metadata—information about the data, such as title, location, author, keywords, relationships, etc.—are important when searching archival collections. In most existing Black Canadian collections there are knowledge gaps in the archival record with regard to this pivotal information. The problem with many image archives is that they are searchable only by supplementary metadata (anecdotal data not provided by the original source), rather than by secondary metadata (descriptive information that covers dates, origin, history, cross-referencing). Since the language that we use to describe the world has changed significantly, it is an ethical question to ask why many archival collections have not considered the contemporary moment of how image archives are being used. On a practical level, this would mean engaging in naming projects where archives ask the community (via social media and/or community webpages) to participate in naming projects, while those who might know the people captured in the images are still alive. For example, The Black Canadian Veterans Stories of War page illustrates this phenomenon. This webpage, founded by a private citizen, Kathy Grant, is part of The Legacy Voices Project, which she started in 2013 in commemoration of her father Owen Rowe, a Second World War veteran. Grant’s Facebook group digitizes and shares photographs and documents that tell the stories of Black soldiers. She has even worked with the Department of National Defence to record these Black veterans’ oral histories.[11] If we consider that most archival collections are processed only once and, as a result, can contain a lot of dated language or metadata that are no longer relevant, and that cultural biases often influence how images are classified in the first place, information about images is not always reliable. What we have then, especially as it relates to Black women in many archival collections, is mislabelled or misinterpreted metadata. In order to illustrate the difficulty posed by unnaming and/or incomplete information in the archive, I analyze six nineteenth-century photographs of Black women in the McCord’s image collection. While this seems like a small corpus, these five women “constitute the sharpest departure from entrenched modes of representing the black female subject” in Canadian visual culture and “these portraits differ dramatically from their painted and sculpted counterparts in the comportment and expressions of the black female sitters who now, as paying customers, gained more control over the representation of their likeness” (Nelson, 2010, p. 30–31). In total, there are six nineteenth-century images of Black women in the McCord’s online collection, and one group image of two Black women and two Black men taken at the turn of the twentieth century and discussed in brief later.

How to “Read” Nineteenth-Century Photographs of Black Women

According to its website, the McCord “celebrates our past and present life in Montreal—our history, our people, our communities.” Without a doubt, it houses one of the most impressive collections of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Canada in the country. It has more than 88 000 objects and 30 840 online oil paintings, watercolours, pastels and charcoal drawings, miniatures, silhouettes, lithographs, etchings, woodcuts, posters, cartoons, caricatures, and drawings, dating from the eighteenth century to present day. In addition to dress, fashion and textiles, Indigenous collections, and decorative arts, its photographic archive is extensive. With more than 1 300 000 images (83 380 online), the McCord’s photographs of nineteenth-century Canada include daguerreotypes, tintypes, and albumen prints of families, documentary photographs, artist portfolios, and images of cameras and photographic equipment from 1840 to the present day. William Notman (1826–1891), one of Canada’s most lauded nineteenth-century photographers, took thousands of images. The collection contains thousands of photographs grouped together in albums, series, and portfolios, which capture a range of people who lived in nineteenth-century Canada, including images of First Nation Peoples and Black Canadians. The McCord’s Notman Photographic Archives, acquired in stages since 1956 constitutes the majority of the McCord’s photographic collection with over 450 000 photographs from the Montreal studio founded in 1856 by Notman and remaining in the Notman family until it was sold in 1935 to another commercial concern, the Associated Screen News, which divided the operations into the historical division, run by Charles Notman, and the commercial studio, Wm. Notman & Sons (Longford, 2001, p. 203). In September 2019, the McCord announced via press release that that collection is now listed in the Canada Memory of the World Register, an honour that has been extended to only sixteen Canadian collections to date (McCord Museum). According to this release, several hundred Notman works have been featured in the exhibition Notman, A Visionary Photographer, organized and hosted by the McCord Museum, and in a book of the same name offered at the Museum’s boutique.[12]

In slavery, many Black women laboured as wet nurses for white children. When these women were photographed in the nineteenth century, their images were then integrated into the culture at large, which was still very much a colonial society. In Canada, there are no known images of wet nurses (though Black women nurses or nannies would have been responsible for feeding their white charges), but there are photographs of Black women nurses and nannies in the employ of whites. While this is not a photographic or art-historic article, it is important to give tangible examples of how, when Black bodies are unnamed and the archival record either does not provide context to the Black body in the photograph or it includes misleading information based on little secondary research, it acts as a form of silence not only of the past, but also the present because we, as viewers, are not able to grapple with who the sitters might have been, why they would have had their pictures taken at such a prestigious photographic studio, and why these pictures were then preserved within the records of white families in Montreal.

Notman gained most of his notoriety by selling pictures of prominent Montrealers, such as the first Prime Minister of Canada, Sir John A. MacDonald, whose picture was taken at Notman’s studio several times. Whether their dress was their own or given to them by Notman, the images of Black women in Montreal between 1867 and 1901 reflect an aesthetic diversity with respect to hair and dress. Thus, the images of carefully dressed, comfortable, and poised Black women in Notman’s photographs are inscribed with deliberate signs of the middle or upper classes, both within the women’s bodies and the studio settings (Nelson, 2010, p. 30). At the same time, since the connoted message (secondary level) of meaning is realized at the different levels of production (choice, technical treatment, framing, layout), which represents a coding of the photographic analogue (the literal image) ( Barthes, 1978, p. 17), analyzing these photographs goes beyond just the subject and into the photograph’s production—composition, pose, objects, aesthetics, and exposure. As Catherine Lutz and Jane Collins remind us in their reading of photographs in National Geographic, “cultural products have complex production sites; they often code ambiguity; they are rarely accepted at face value but are read in complicated and often unanticipated ways” (Lutz and Collins, 1993, p. 11). Similarly, the structure of the photograph is not an isolated structure; it is in communication with at least one other structure: namely, the text—title, caption, or article—accompanying every photograph (Barthes, 1978, p. 16).

Nurse and Baby, Copied for Mrs. Farquharson

Anonymous, Nurse and Baby, Copied for Mrs. Farquharson, 1868. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, albumen process, 8.5 x 5.6 cm.

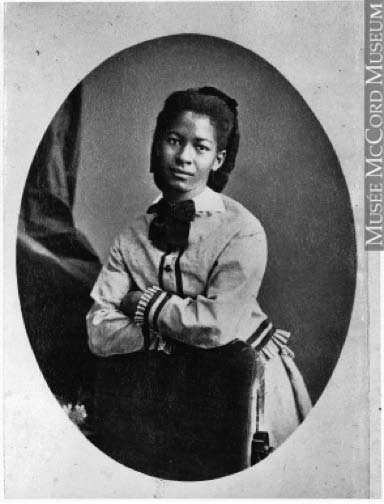

In Nurse and Baby, Copied for Mrs. Farquharson (1868),[13] a nameless Black female sitter wears a fancy dress with large sleeves, and her hair is parted down the middle and likely tied in a chignon at the nape. The word “chignon” comes from the Old French chäengnon, for the nape of the neck; the movement of chignons up and down the head was a major element in nineteenth-century hair fashions (Rifelj, 2010, p. 59). Chignons were popular during the Victorian era and, in this style, hair was often parted down the middle and arranged in a roll or tied in a knot at the back of the head, but there were also many variations on the style. Scholars of nineteenth-century fashion and dress have noted that the expanding skirt of the 1850s was given buoyancy by flounces (a strip of decorative gathered or pleated material attached by one edge) and, by the middle of the decade, the hoop petticoat dress with pagoda sleeve, a wide, bell-shaped sleeve popular in the 1860s that became quite large (Stamper and Condra, 2009, p. 96–98). I am not a nineteenth-century dress expert; however, in order to “make sense” of an image like this, one would have to know that Black women typically did not wear fancy dresses of this nature if they were employed in the capacity of maids or nurses, unless they were given hand-me-down dresses from their employers.

Not every Black woman photographed in the 1850s or 1860s who is nicely dressed is wearing the clothes of her employer. However, through being photographed, sitters became part of a system of information, fitted into schemes of classification and storage and pasted into the family album of her employer (Sontag, 1977, p. 156). According to Lutz and Collins, “photographs of familylike groups created a sense of order and logic that validated Western family arrangements and familial emotions, regardless of how the people photographed had come together or what their social relationships, in real life, might be” (Lutz and Collins, 1993, p. 30). The bust located in the background of the image connotes the wealth of the sitter’s employer, not the sitter herself. But as it relates to the connotative level of meaning, the fact that the Black sitter’s face is as visible as the white child in her hands is an incredible photographic feat in the nineteenth century. Additionally, photographic representations of Black women with their charges were common for practical reasons. First, small children would not sit still for long exposures required by early photography, and often a grown-up was included in the portrait in order to steady the child (Willis and Williams, 2002, p. 129). Second, as a servant, Black nurses and/or maids were required to serve their employers and the child; in this respect Black women were often no more than props, like headboards, to ensure the success of the child’s portrait (Willis and Williams, 2002, p. 129). Thus, in this photograph labelled “Nurse and Baby, copied for Mrs. Farquharson” (this is Notman’s original naming), both the Black sister and infant pictured are relegated to a status subordinate to that of Mrs. Farquharson, owner of the image. The naming of the image further suggests the Black female sitter’s intended marginality within the frame—the subject of this image remains Mrs. Farquharson, even as she is absent from the frame. Researchers ultimately must understand that such images are not as they appear—a Black woman holding a white baby wearing a dress—but these speak to a more nuanced milieu and photographic message. The archive ultimately plays a role in subject-making, not just the role of repository or safe-keeper of images from our past.

Mrs. Cowan’s Nurse

William Notman, Mrs. Cowan’s Nurse, 1871. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, albumen process, 8 x 5 cm.

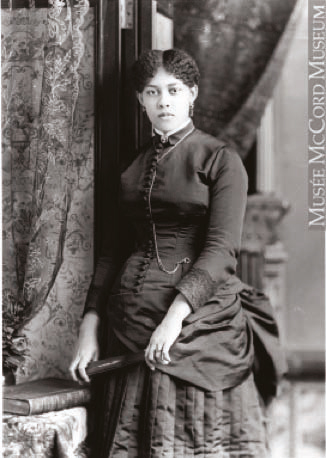

Scholars, such as art historian Charmaine Nelson, have written about other images in the McCord’s collection, such as Mrs. Cowan’s Nurse (1871).[14] Although the young Black female’s white charge is absent, her power and authority is mapped onto the image through the process of naming that displaced the Black nurse’s name and replaced it with that of her white female employer. The portrait that foregrounds the employer’s name was probably taken at the request of Mrs. Cowan, most likely white, as a status symbol that reflects the wealth and position necessary for the employment of a private nurse (Nelson, 2010, p. 31). Significantly, there are eighty-nine photographs in the Notman online archive of white women nurses (e.g., nurses with a baby and/or multiple children, group portraits of graduating nursing students and/or General Hospital nurses, and nurses in portrait photographs taken outdoors) who are similarly unnamed, so this practice of not naming women in one’s employ by their name was typical across the board. The difference between Black nurses and white nurses in terms of their photographic representation is that the former are photographed wearing elaborate fancy dresses while the latter are typically captured in photographs wearing simple black or beige dresses. There are also two examples—Miss Woods, Nurse, 1898 and Miss Pettigrew, Nurse, 1895—where white women nurses appear alone in a portrait photograph, are given names, and are dressed in attire that they likely wore on the job.[15] These photographs of white nurses are rare and reflect a level of agency that was not typical among the servant class, irrespective of race.

Wm. Notman & Son, Mrs. Allan’s Nurse and Baby, 1898. Silver salts on glass—Gelatin dry plate process, 17 x 12 cm.

William Notman, R. Masson’s Nurse and Child, 1862. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper—Albumen process, 8.5 x 5.6 cm.

Wm. Notman & Son, Miss Woods, Nurse, 1898. Silver salts on glass—Gelatin dry plate process, 17 x 12 cm.

Wm. Notman & Son, 1893, Group of General Hospital Nurses, Silver salts on glass—Gelatin dry plate process, 20 x 25 cm.

There is some catalogue information for Mrs. Cowan’s Nurse in the McCord’s online collection. Specifically, in its thematic section called “Straitlaced: Restrictions on Women,” it is confirmed that the photograph was taken at Notman’s studio. The description adds that well-to-do families frequently had photographs taken of their staff, who were often identified by their job rather than by name; as well, women of colour sometimes had jobs that put them in intimate contact with their employers.[16] There is no information, however, that would differentiate how we should “read” images of Black women nurses uniquely different to white women nurses. I would argue that because Black women nurses are significantly underrepresented in the archive—this might not have been the case in the nursing profession—it can give the impression that Black women nurses’ working experiences mirror those of white nurses in nineteenth-century Montreal. And that just might not have been the case. The profession was largely dominated by white women during the period. Most notably, after the 1890s, most white nurses were photographed in formal white nurses’ uniforms either alone or as part of a nursing group at a Montreal hospital; there are also group portraits of McGill University’s (white) nursing school graduates in the collection.

Baby Paikert and Nurse

Wm. Notman & Son, Baby Paikert and Nurse, 1901, Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, 8.5 x 5.6 cm.

There is one existing image in the Notman Photographic Archive of a Black nurse wearing a formal nursing uniform. In Baby Paikert and Nurse (1901),[17] a Black nurse wears a white uniform and nurse’s cap while gazing onto a white baby, who is sitting on her lap. This photograph also reveals how pigmented skin was difficult to capture in photographs in the nineteenth century as the sitter’s facial features are hardly visible. Often, one of the ways in which subjects were denigrated in photographs was by hiding people in dark shadows or by placing the camera intentionally in bad angle in order to alter the observer’s gaze (Sontag, 1977, p. 170–71). The photograph’s focal point is the baby, not her Black nurse. The Black nurse’s uniform also includes a white apron. According to Christina Bates, the first nursing caps were in the style of ladies’ breakfast or morning caps, worn close to the back of the head, with frilled or goffered edges, and some with streamers down the back (Bates, 2011, p. 171). Whereas fashionable ladies’ caps were made of velvet, lace, and ribbons, the restrained nurses’ caps were white, probably made of linen or muslin (Bates, 2011, p. 171). Like the princess-style cotton dresses, ladies’ caps were meant to be worn in the home, and caps for nurses, like those for household servants, persisted past the 1870s (Bates, 2011, p. 171). By the mid-1890s, as nursing schools proliferated, “caps grew in variety and exuberance, the brim changing back and forth from gathered, goffered, and frilled, and the crowns from peaked, triangular, and bifurcated, the fabric from transparent scrim to muslin” (Bates, 2011, p. 171). Thus, photographic portraits of nurses are a reminder that, even though Black and white women were in the same state of employ, the way they dressed for photographs differed. What would it mean for the archive to note the subtle difference in nurses’ dress between the 1870s and the turn of the twentieth century, with regard to uniforms, employment, and race?

Miss Guilmartin and H. Evans and Lady

Wm. Notman & Sons, Miss Guilmartin, 1885. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, 17 x 12 cm.

William Notman, H. Evans and Lady, 1871, Silver salts on paper mounted on paper—Albumen process, 9 x 5.6 cm.

Notman & Sandham, Miss Guilmartin, 1877, Silver salts on paper mounted on paper—Albumen process, 17.8 x 12.7 cm.

Hendrick Cezar & Frederick Christian Lewis, Sartjee, the Hottentot Venus, 1810, Hand-coloured etching, 357 mm x 221 mm.

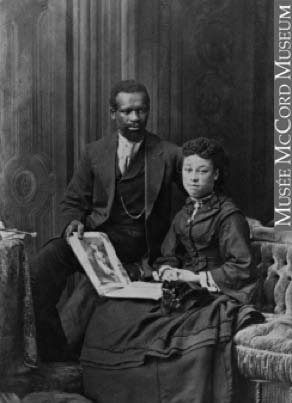

Significantly, not all Black women photographed at Notman’s studio were posed under the employ of white women. For example, the clothing, jewelry, coiffures, and accessories, and the décor, drapery, columns, books, and furniture in Miss Guilmartin (1885), Miss Guilmartin (1877), and H. Evans and Lady (1871)[18] are those of “ladies.” Both women are positioned firmly within an interior space of wealth, knowledge, learning, and leisure (Nelson, 2010, p. 30). In H. Evans and Lady, there is no archival description; however, it was extremely rare in the nineteenth century for a Black woman and man to be photographed together, and for the male subject to be given a proper name, while the female subject is given the title of “lady.” Nineteenth-century visual representations of the enslaved Black male body prior to the American Civil War had idealized the emancipation moment by exulting seminude male figures whereby Black men held up broken manacles and kneeled in gratitude to formally clad whites, who were often staged as God-like figures (Savage, 1999, p. 77). Additionally, post-Emancipation images produced by the dominant culture depicted Black men, women, and children as caricatures, such as the derogatory images of the servile Uncle Tom, hypersexual Jezebel, and unkempt Sambo. Before the Civil War, a Black woman who was of mixed race was permitted to become a lady provided that “providence procured for her proximity to a white gentleman” (Brody, 1998, p. 17). In H. Evans and Lady, Miss Guilmartin (1885), and Miss Guilmartin (1877), there is no identifiable white person for whom the viewer can “place” the female sitter as enabling her status to that of lady. It is extraordinary that both images denote and connote the Victorian ideals of lady. The Black female sitter in Miss Guilmartin (1885) and Miss Guilmartin (1877) has a strong, direct gaze. While her hair is parted down the middle and likely tied in a chignon, her dress aligns her body with that of the “proper” Victorian lady in the 1885 photograph, and, in the 1877 image, her hair is combed and tied in a chignon at the top of her head, while her dress is similarly that of a lady, even though the images were taken twelve years apart. The analogical content of both images, to borrow from Barthes (1978, p. 17), is constructed through the placement of pillars, books, a family album, drapery, and furniture.

Wm. Notman & Son. G. Conway and Friends, 1901. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, 17 x 12 cm.

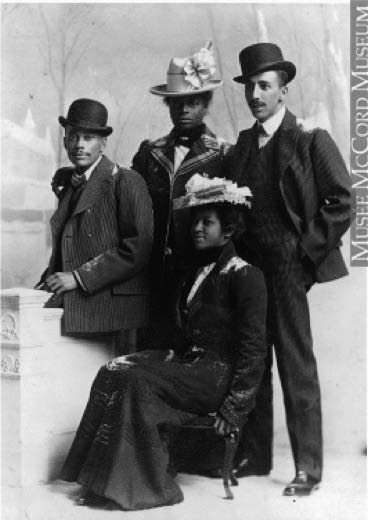

If we consider that 1900 to 1940 was the period defined as the time of the “New Negro,” reflecting the explosion of creative endeavors that gave national prominence to fashion, artists, educators, historians, and philosophers in America (Willis, 2000, p. 35), the presence of these three photographs within a Canadian archive are extraordinary and point to the extent to which some Black Canadians were, like African Americans, reimagining the “self” and Black identity through images. Additionally, in the sixth photographic portrait of Black women—the only image with Black women and men sitters—in the McCord’s collection, G. Conway and Friends (1901), the increased importance of appearing fashionable is made apparent through the sitters’ wearing of turn-of-the-century fashion hats and outer coats. The New Negro used photography in purposeful ways to rescript their identities in a new century; as such, the sitters in this photograph should be read as having commissioned their photograph (as reflected in the image’s title), and the intimacy of the poses is an intimacy that is very rarely captured in photographic records of Black subjects in Canada at this time.

The agency of subjects’ participation and responsibility in making their image has been defined as “the act of confronting identity and taking control of the image; agency equals power” (Willis and Williams, 2002, p. ix). Did these Black women wilfully walk into Notman’s studio to have their portraits taken? Did they have power over their pose? Were they consulted in the naming of their photographs? These questions regarding Black women’s bodies and agency point to the contradictions in the history of Black women’s photographic images; namely, while some Black women (such as Black nurses) might have lacked agency to choose their representation, other Black women “agreed to participate in displays, or posed for photographs, and thus were not victims. Making choices as individuals, they were as much agents of their exploitation as anyone, but they might not have regarded themselves as exploited” (Willis and Williams, 2002, p. 197). Using the same photographic technologies and tropes, Miss Guilmartin (1877) and (1885) and H. Evans and Lady (1871) ask viewers to think about how Black individuals could mutually affirm their places in an imagined community rooted in discursive fantasies of national character; the family photograph album, for example, which offered individuals a colloquial space in which to display practices of national belonging (Smith, 1999, p. 6), rests on the laps of the sitters in H. Evans and Lady (1871).

Importantly, the puffing at the back of the skirt, as seen in Miss Guilmartin (1885), had evolved by the 1880s into what became known as the bustle dress. Bustles, worn off and on between the 1870s and early 1900s, were one of the many foundation garments worn by nineteenth-century Victorian women. Instead of the large bell-like petticoat silhouettes of the early 1860s, dresses began to flatten out at the front and sides, creating more fullness at the back of the skirt. There is much evidence to connect the nineteenth-century bustle, the extra padding at the back of a dress that gave the appearance of a large buttocks, worn by middle-class Victorian women with the circulating image of Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, also known as the “Hottentot Venus.” When Baartman, a South African Khoi or San woman of “mixed blood,” was exhibited as a curiosity in Europe, first in London and then Paris, from 1820 to 1815, she became an emblem of European fascination with the body and sexuality of black women (Willis and Williams, 2002, p. 59). Like the Sable Venus who preceded her, Baartman was “given a sobriquet linking her to a Western icon of physical pulchritude and sexual desirability. Yet by European standards Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, differed from Baartman as day from night” (Willis and Williams, 2002, p. 59-60). Baartman occupies a special position in the genealogy of a race/gender visual, as an arbitrary starting point, which precedes photography, because she was the first Black woman to be documented, her image widely circulating through drawings, watercolors, and writings, and this in addition to the preservation of her private organs for public display. In the visual and scientific discourses of the nineteenth century, the buttocks of the Hottentot were a “sign of the primitive, grotesque nature of the black female” (Gilman, 1985, p. 219) and, paradoxically, also an object of white men’s sexual desires. Thus, many historians have noted that the bustle dress, which accentuated the buttocks of the Victorian woman, mirrored the fascination scientists and colonialists had with the buttocks of Black women during the period. Bustles may have been considered “fashionable,” but they quite visibly resembled the circulated image of the “Hottentot Venus.” While the archival description does not include any information on the fashion of Black women, there is information about Miss Guilmartin (1885) that is quite detailed compared to other Black women in the collection—named and unnamed.

According to the McCord’s descriptive data accompanying the image,

The English and the French considered themselves distinct races, each thinking their own characteristics and traits to be superior to those of the other. But as northern Europeans, they also believed themselves to be members of the small family of “superior” races. Amerindians, the Irish, southern Europeans, Asians and Blacks were all considered inferior human beings. Taboos against socializing with people from other racial groups did not stop Mary, an Irish immigrant, from marrying Shamrach Minkins, Montreal’s famous refugee from American slavery. In fact, interracial marriages were not entirely unknown, especially in the poor and working-class urban districts. Nevertheless, taboos against miscegenation were so deeply ingrained that most Canadians were unlikely to entertain the idea of marrying outside their own group. If they did, their family and even the community might intervene to force an end to the relationship.[19]

There is a lot to unpack in this blurb. How should we read it against the image of Miss Guilmartin? What does it mean that an image of a Black woman is accompanied by a history of English and French racial superiority? Why should we assume that Miss Guilmartin is of mixed race (note the reference to miscegenation)? Given the lack of archival information regarding her place and date of birth, as well as ancestry, other than her skin tone, how can we be certain of her genus? As Arthur Riss opines of the nineteenth century, “Hair functioned in both scientific and public discourse as a parallel to skin color: it was typically cited as a means by which human groups could be empirically sorted, as a natural part of the surface of the body, like skin, that must possess inherent significance” (Riss, 2006, p. 97). Furthermore, since scientific and popular discourse was obsessed with how the body signified, “it was not unusual, in fact, for some to claim that hair served as a better indicator of racial identity than skin color” (Riss, 2006, p. 98). Miss Guilmartin’s hair is course textured; therefore, regardless of her skin colour, she was a Black woman who may or may not have been of mixed race. This is the kind of nuance that is important to include in an image archive since we, the living, become the voice for the voiceless and in “marking” their bodies with descriptive words, we can erase the truth of who they were.

The descriptive paragraph does however explain that Miss Guilmartin was likely an educated woman, which is probably true given her naming as Miss. However, while it is confirmed that the photograph was produced in the Notman studio, it is speculated that Miss Guilmartin was probably visiting from out of town, perhaps even the US, as her name does not appear in the Montreal directory at the time (McCord Museum). This speculation, while on the face of it seems logical based on official records, when you dig a little bit deeper, it also speaks to historical biases in official recordkeeping. In order to think about history as narrative in the archive, we must recognize where archives neglect to consult academic researchers, such as Black Montreal historians, to fill in knowledge gaps.

In A History of Black Montreal, Dorothy Williams explains that “the family records of one local historian reveal that when his first ancestor arrived in Montreal in the late 1840s, there were only four black families living in Montreal at that time” (Williams, 1997, p. 27). She explains further that there were not many Black people living in Montreal in the nineteenth century, but historians wrongly assume that if Blacks had been in Montreal in significant numbers much more would have been written about them (Williams, 1997, p. 28). This conclusion does not consider clandestine Black immigration, particularly in the summer of 1831 when it was estimated that 10 000 unregistered immigrants arrived in Montreal then, and one observer wrote that Blacks from the US, Scotland, Ireland, Australia and the West Indies were included in this group (Williams, 1997, p. 28).

At the same time, by the late-nineteenth century and through twentieth-century, “immigration officers often registered people by their place of birth rather than by racial criteria, which misrepresented hundreds of immigrating blacks. This was particularly true for blacks who came from England, Europe or elsewhere overseas via American ports. The official records also do not consider illegal immigration” (Williams, 1997, p. 40). Thus, Miss Guilmartin might have been visiting from America, but she might have resided in Montreal, which explains why she had her photograph taken twice at the same studio (in 1885 and 1877). If we are to place Black subjects in Canada’s archive, what role does myth making and nostalgia play in how Black collections are itemized, catalogued, and displayed?

Why Race Matters in Framing the Archive-as-Subject

There is a consistent institutional practice of overlooking race and class in nineteenth- century photographs. The ways in which Black women self-represented through photography, in particular, the way they dressed, styled their hair, and appeared “fashionable” reveals plenty about the sociocultural milieu of nineteenth-century Canada. In the 1850s, for example, Dr. Robert W. Gibbes, a nationally recognized palaeontologist, hired local daguerreotypist Joseph T. Zealy to make photographic records of first- and second-generation slaves on plantations near Columbia, South Carolina, for Swiss-born Louis Agassiz, the natural scientist and zoologist from Harvard University (Williams, 2002, p. 185). Using the frontal/profile combination that was first used in ethnographic photography, Zealy documented slave women and men in half- and full-length views stripped to the waist or, in the case of some of the men, totally naked. The result was a denial of Black women’s (and men’s) humanity and also a control over the representation of their bodies, removing all agency and power from their naked bodies, not to mention, as a reified representation of blackness, it also helped to perpetuate beliefs in the “unclothed” as uncivilized Black body. The technological advances in visual imagery that occurred from the mid-nineteenth century onward would supersede eighteenth-century paintings and print culture in terms of their imperial function. Prints and photographs crossed almost seamlessly between “overlapping visual cultures as independent works of art, as surrogates for paintings and for each other, and as illustrations and other visual ephemera” (Sperling, 2010, p. 296).

Prints and photographs were symbolically interconnected with ideas, themes, and materials related to exchange, reproduction, and consumption. For the first time, printmakers and photographers were able to offer relatively inexpensive pictures of people and places, which could then be proudly displayed on living-room walls, or stored privately in cases or folios (Sperling, 2010, p. 296). If the nineteenth century was the age of mechanical reproduction, wherein the image became the most valued visual form, and print and photography were its agents, visual forms were also subject to the latent demands in society, especially in relation to the imperialist role that they served in documenting racial difference in North and South America. In her article “Icons of Slavery,” Margrit Prussat examines how photography served as an important medium for the construction and communication of a modern Brazilian national identity related to empire (Prussat, 2009, p. 203). Many of the first photographers in Brazil were European or of European descent, and, in the photographs of urban slavery, “people are represented mainly as street-vendors, household-slaves, or carriers—professions that were very common among the African population” (Prussat, 2009, p. 207). Circulating photographs served an imperialist function similar to that of literature and travel writing, but a daguerreotype was still a luxury item in the 1850s, and, given the plate size, one half of a full plate, it would have been quite expensive, and so was typically made for a wealthy client or the daguerreotypist himself.

Thus, the photographic portraits of Black women in the McCord’s collection provide us with a glimpse into how Black women visually represented themselves in the emergent medium of photography in a post-slavery milieu. Unlike the portrait painter, who had to undergo extensive training in order to create a portrait in the likeness of a person, the photographer, outfitted with a camera and a tripod had only to aim and shoot, producing an easily identifiable likeness (Smith, 1999, p. 60). These photographs are a more historically accurate picture of how Black women in colonial Canada scripted their own identities through visual representation. However, the question of Black women archival records is complicated by a lack of detailed information regarding what their names were, who they were, and where they lived.

Ultimately, the McCord Museum is not distinct from other archives with Black collections across the country in terms of either misinterpreting historical Black bodies or rendering their subjectivities invisible due to their un-naming and lack of descriptive data not solely about the sitters’ dress, pose, and objects, but also about the photographic composition (i.e., gaze, exposure, shadowing), time period, and relevance of location. Black Canada has not been adequately attended to in archival collections. As Boye poignantly observes in her DCD Archives work previously mentioned, when she was shown a photograph depicting four dancers—Don Gilles, Janet Baldwin, Dorothy Dennenay, and Bill Diver—who were named and identified as members of the Volkoff Canadian Ballet by the photograph’s donor Jim Bolsby, the first general manager of the National Ballet of Canada, and behind them, a fifth seated performer, who was an unnamed Black woman, she, like I, also wondered why. Based on her historical knowledge of Black Canada and performance, Boye speculated that this woman was Portia White. Born in Truro, White was the first Black Canadian singer trained in Canada to reach an international stage. By the 1940s, she was a well-known person, in Canada and abroad, yet, in the archival memory of this photograph, she remained unnamed and unexamined until Boye, a Black woman, questioned her unnamed body.

Boye used a number of historical facts to support the hypothesis that the unnamed woman was White. First, White was living in Toronto during this era—the photograph was from the 1940s, the height of White’s acclaim—and she shared more than one programme with the Volkoff company, but ultimately, what helped Boye put a name to this nameless Black woman was the following: “White is the only known black woman, amongst a group of historians, whose talent could have found her on this stage despite racial boundaries” (Boye, 2013, p. 18). In the end, Boye asked the questions: Who else could it be? Is this enough to assume an identity? And what is at stake if the assumption is wrong? These are the very questions that we need to push archives to at least, at a bare minimum, consider before placing an unequivocal “unknown” or “unidentifiable” label onto a Black woman in the Canadian historical record. Is it impossible to figure out who they were? “While the missing identity may not have anything to do with race, it is in essence an absence and so eventually a possible erasure from dance history, performance history, Canadian history, and African-Canadian history” (Boye, 2013, p. 18).

Conclusion: Renaming Black Canada and the Archive

In 2017, Julie Crooks curated a photographic exhibit at the Art Gallery of Ontario called Free Black North. The exhibit featured 27 tintype photographic portraits of African Canadians—men, women, and children—who lived in southwestern Ontario in the mid- to late nineteenth century. This was the first exhibit that I have attended at an art gallery where not only the names of the sitters—most of whom were descendants of African Americans who, after fleeing the US, established communities in Ontario’s small towns like Amherstburg—were given, but also details about who they were, what their family narrative was, and how we, in the present, should “read” their image—not just as an image of Black people living in nineteenth-century Canada, but also through the context of freedom. As Brian Thomas explains, the “social conception of Canadian national identity and the discursive practices that express it in public spheres ignores, or insufficiently appreciates, the legacy of human chattel slavery in Canada” (Thomas, 2014, p. 595). “There is not much in the public memory of it; … nor of its structural imprint on institutions or on subsequent federal policies (e.g., legal rules offered to ban black persons from entering the country) or provincial rules (e.g., official legal rules of segregation),” he writes further (Thomas, 2014, p. 595). In order to adequately address the unnamed Black woman in the archive and/or the misrepresented Black bodies, we need to have a conversation about Canadian slavery, de facto segregation up until the 1950s and 1960s, and how these legacies—which have never been addressed in a substantial way—help to frame institutional memory, practices, and the notion of what constitutes the Black archive in the first place. “A denial or ‘forgetting’ of past practices of institutional racism,” Thomas asserts further, “has the result of characterizing present acts of racism as isolated incidences, rather than indicators of systemic oppression” (Thomas, 2014, p. 595).

In previous works, I have called for a rethinking of Black Canadian identity through a renaming process, especially as it relates to the issue of memory and the Black collective experience (Thompson, 2014). Naming, unnaming, and renaming have been part of the Black experience since the seventeenth century, when the first slave ships landed on the shores of what is now North America. Enslaved Africans were forced by Europeans to adopt the names of their slaveowners in an attempt to remove them from their African lineages. The ability to adapt to new names, transforming into a bricolage that retains a past while embracing an unknown, is part of the Black narrative. I am not alone; other members of Black Canadian community are also calling for a Black Canadian renaming project. Anthony Morgan, a lawyer who practices in the areas of civil, constitutional, and criminal state accountability litigation with a specific focus in antiracist human rights advocacy and anti-Black racism, wrote an article for Ricochet.ca where he argued that when you make considerations for place, space, and belonging, questions of Black people and our presence in Canada are a perpetually contested topic. “Despite our country having an official mantra of multiculturalism,” he explains, “Black people exist on or beyond the margins of official myth and memory of Canadian history, identity and society” (Morgan, 2019). With regard to naming and renaming, Morgan proposes a new term, which “more effectively captures the routes/roots of the Black presence in Canada” (Morgan, 2019); that is, “forcibly displanted Africans.” This name would replace anachronistic and inaccurate languaging of Black presence and experience in Canada, moving us beyond the un-useful term of “settler,” he argues, and it would also offer a description of Black people and presence in this country that is ultimately much more consistent with the factual histories and realities of Canada’s African heritage (Morgan, 2019). What role would a Black Canadian archive play in this renaming process?

When a name is recorded as “unknown” amongst a list of known identities, and Black women are, as a result, not searchable and, therefore, they cannot be found in the record, it signals that we do not matter. If we are not named, we are not found, and if we are not searchable, this continues the institutional practice of ignoring the stories of people who do not fit within the narratives of Canada as a “white settler” nation. In order to contend with the problem of unnaming in Black Canadian archives, I believe collections will need to be mapped from coast to coast. While this is an ambitious project, in my opinion, it is long overdue, and if it is left to institutions to decide upon the Black archival record, the reality is that not much will change. Why are there unnamed Black women in the archive when, in many cases, they worked for a white family raising their children or cared for them in ill-health as nurses, and then, because they were of such importance to that family, they had their photograph taken at a professional studio—a practice that would have been quite expensive in the nineteenth century? On an ethical basis, how can we continue to allow these records to remain unidentified?

Archives must begin to ask tough questions, and, as we move toward recontextualizing an archive’s memory, the discussion needs to move beyond race, photography, and archives to instead consider the need to find frameworks for contextualizing doubt (Boye, 2013, p. 20). What should be done when there are unknown subjects or missing information in archival records? What does it mean when we name or do not name someone? Is it because we do not know, or because we are not interested in finding out? A wrong identification could incorrectly alter a number of historical trajectories, and the more we resist naming the unnamed, the more we will continue to deny the corporeal subject of Black archival records, their actual existence and unique experience (Boye, 2013, p. 20). Silencing Black bodies in the archive continues the legacy of archives as mere colonial depositories, reinforcing centuries-long tropes that denied Black people agency, and also fails to acknowledge what their self-portrait would have meant historically, and what it continues to signify in the present. How can we continue these practices in the present if the demographics of so many communities are changing, and there is increased demand from racialized persons to “see ourselves” reflected in national discourses of belonging, both to Canada’s past and present?

To pursue a project of naming Black subjects in the archive is political, and it will make some people uncomfortable because it will appear as though their knowledge, as archivists or librarians, is being called into question or being somehow delegitimized. Such change, however, requires courage. In the UK, the BCA was formed through independent and community-based heritage projects and because of archival activism, which had as its aim to use community archives and heritage for community empowerment and social change; these projects were not politically neutral, but arose from and were part of social movements with broad political, cultural, and social agendas for transformative change that ultimately changed mainstream society, as well (Flinn, Stevens, Shepherd, 2009, p. 84). For Ellen Ndeshi Namhila, a desired outcome of her critique of Namibia’s archive would be that it “contributes to a major policy review of legislation, policies, guidelines, standards, principles, and procedures governing the archives and to the development of a programme of archival ‘affirmative action’ with practical steps to rectify the wrongs of the past” (Namhila, 2019, p. 122). I firmly believe that the archive is not just a window into our past but a prescriptive guide for how we contend with the present. It is also a glimpse into who matters and who does not as we look toward our future. It is time to make Black Canada’s archival memory matter—for our past, present, and future.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Ryerson University’s Faculty of Communication & Design’s seed grant for 2018–2019. Special thanks to Emilie Jabouin, PhD Candidate, Ryerson University and York University’s joint program in Communication & Culture, for her assistance. I would also like to acknowledge McGill University, the McCord Museum, and the Archives of Ontario where I conducted the field work that appears in this article. During the 2012–2013 academic year I won a museum fellowship to conduct research at the McCord Museum in Montreal. The project, titled “Black Women and the Photographic Canadian Portrait in the Nineteenth Century,” was an examination of nineteenth-century photographs of Black women in Montreal and serves as the basis for the analysis in the present article.

Notes

-

[1]