Abstracts

Abstract

The US government lacks robust and accurate records of its military personnel. In this context, we argue that attending to veterans’ recordkeeping practices matters to honouring their service to the nation. However, recordkeeping skills are not currently part of the official curriculum of active service members or veterans. Considering this situation, we ask, How do veterans in the US document their service? What are the uses of veterans’ records and recordkeeping practices? Drawing from personal management of information (PMI) and rhetorical genre studies (RGS), we conducted focus groups with veterans and active service members. We found that these individuals attempted to preserve their personal records by creating love-me binders (LMBs) – a genre of records, shaped by the history of recordkeeping practices in the US Armed Forces, that supports military personnel in keeping track of their service. As a genre, love-me binders serve a rhetorical purpose: demonstrating that veterans and sometimes their relatives are eligible for benefits such as health care. Future work should consider opportunities to support veterans in creating and managing LMBs, investigate the creation and management of military records in context, and explore additional domains where records created in the workplace impact workers’ personal lives.

Résumé

Le gouvernement des États-Unis ne possède pas de la documentation précise et complète sur son personnel militaire. Dans ce contexte, nous affirmons qu’une bonne gestion des documents est importante pour honorer les services à la nation du personnel militaire. Par contre, des compétences de gestion de ces documents ne font pas partie des responsabilités des membres actifs ou des vétérans du service militaire. En constatant ceci, nous attirons l’attention sur les questions suivantes : Comment les vétérans aux États-Unis document-ils leur service? Quelles sont les utilisations et les pratiques de gestion des archives des vétérans? En nous basant sur la gestion des informations personnelles (PMI) et les études de la rhétorique (RGS), nous avons créé quatre groupes de discussion avec des vétérans et membres en service actif. Nous avons remarqué que ces individus ont tenté de préserver leurs documents personnels par la création de love-me binders (LMBs), un type de documents – influencé par l’historique des pratiques de gestion des documents dans les forces armées des États-Unis – qui soutient le personnel militaire en gardant une trace de leur service. Comme type de documents, les love-me binders servent un but rhétorique : ils contribuent à démontrer que les vétérans – et parfois leurs proches – sont éligibles à des bénéfices, notamment à des soins de santé. Des approches futures doivent considérer les opportunités de soutien aux vétérans en créant et assurant le maintien des LMBs. De plus, elles doivent envisager une analyse sur la création et la gestion des documents militaires et leurs contextes, tout en explorant des domaines associés où les documents créés au travail ont un impact sur la vie personnelle des travailleurs.

Article body

1. Introduction

In this article, we aim to apply a rhetorical genre studies (RGS) approach to the study of personal records. Specifically, we investigate love-me binders (LMBs). We understand LMBs as a hybrid genre of military records that spans the workplace and home domains. LMBs are created in the workplace when military personnel are still active in service. However, unlike most workplace records, LMBs make their way into the home space. LMBs allow veterans and their immediate relatives to access certain benefits, such as education and health care. Because they affect access to these benefits, LMBs are of interest in terms of their rhetorical purposes and as an instance of a genre that operates in the space of personal digital archiving (PDA). Specifically, we seek to answer three questions: How do veterans document their time of service? What challenges and concerns do veterans face while engaging in their recordkeeping practices? What are the rhetorical uses of veterans’ recordkeeping practices? Finding answers matters because these questions highlight opportunities to extend the RGS approach into the space of personal records.

The remainder of this article is divided as follows:

-

In the background section, we introduce the domain of military records and the challenges in documenting recent wars.

-

In the conceptual framework section, we contextualize RGS and PDA as subdomains within the broader field of human information behaviour (HIB). We also highlight how information flows within the Armed Forces and justify the importance of understanding veterans’ recordkeeping practices and their challenges.

-

In the methodology section, we explain how the COVID-19 pandemic forced our team to switch from physical to virtual focus groups. We summarize our data collection protocols and offer descriptive statistics about our participants.

-

In the results section, we present and discuss veterans’ motivations for engaging in personal archiving practices. We then devote most of our discussion to describing love-me binders. We focus on the rhetorical uses of these binders and the challenges veterans currently face in maintaining these records.

-

In the discussion section, we emphasize the ways in which love-me binders represent an unofficial but widely spread genre that records social practices among all United States Armed Forces branches to support veterans in accessing benefits.

We also notice that these binders serve as essential tools for veterans to reminisce and give meaning to their experiences of military service. Finally, we call for records management and personal archiving practitioners to collaborate with veterans in enhancing their recordkeeping practices. We argue that such an intervention is a meaningful way of valuing veterans’ service.

2. Background of Military Records

In some professions, such as military service, official records may be incomplete, inaccurate, and sometimes inaccessible to the public.[1] A study about recordkeeping practices in Iraq and Afghanistan revealed significant gaps in the operational records of these two wars.[2] While deployed units must abide by strict standards to produce documentary evidence of their operations, a complex combination of information policies and field demands complicates the fulfillment of this mandate.[3] The gaps in operational records from Iraq and Afghanistan result from several factors such as lack of clarity over document ownership, poor management of existing records, a shift toward information technologies that is divorced from a long-term digital preservation strategy, and career incentives that emphasize operational success but not recordkeeping.[4]

Taking inspiration from prior works on RSG and PDA, we explore personal recordkeeping practices among active service members and veterans of the US Armed Forces. Specifically, we aim to understand what kinds of personal records veterans preserve and what these records mean to them. We also strive to discern the organization and preservation practices and resources veterans engage with. Finally, we endeavour to elucidate the main challenges veterans face in their quests to organize and preserve their records. To accomplish these goals, we focus our attention on love-me binders (LMBs), a genre devoted to documenting veterans’ service time.[5]

3. Conceptual Framework

The field of human information behaviour (HIB) is concerned with how people organize, forage, retrieve, and use information in both personal and professional contexts. HIB theory makes a distinction between knowledge and information. Whereas knowledge is individually experienced but non-transmissible, information is a transmissible representation of knowledge from an individual, group, or organization. However, the knowledge that one person draws from received information may differ from the knowledge held by the person emitting that information.[6] This gap between knowledge and information occurs because the actors involved engage in sense making throughout encapsulation, transmission, and reception.[7] In other words, people employ affective, creative, and action- oriented behaviours, which vary from individual to individual, leading to differing interpretations of the same information.[8]

3.1 A Rhetorical Approach to Personal Records

One approach used in HIB to explore the socio-cultural circumstances of sense making in personal and professional contexts is rhetorical genre studies (RGS). The RGS paradigm views records as means of sense making. Expressly, records are understood as amalgams of text and context.[9] The context prompts the text and is, in turn, generated through the enactment of the text. The text and context of records are characterized by an ongoing dialectical interplay and culturally shaped constructs.[10] Furthermore, records are not objective and discrete but instances of social interactions; that is, records result from different stakeholders acting together to pursue their own differing purposes.[11] Records can be grouped based on how the knowledge that produces them is regulated, codified into specific forms, and altered by people and their communicative activities. These groupings are known as genres.[12]

The social action that produces genres is rhetorical because its purpose is to persuade.[13] For instance, a study of records and recordkeeping practices of the 4-H movement in the Progressive Era found that, through recordkeeping, the sponsors of the 4-H program managed to advance their goal of promoting new technologies and science to make agriculture more efficient.[14] Likewise, a study of an unofficial inquiry among unionized workers in Italy showed that records supported the worker movement in challenging unjust conditions in the workplace.[15]

RSG approaches in records management have adopted a broad range of methods incorporating naturalism, ethnomethodology, ethnography,[16] historiography,[17] case studies,[18] taxonomies,[19] and essays.[20] Studies using these approaches have explored the process of constructing organizational identities, problem solving, and the politics of records.[21] Furthermore, a recent study of medical patents in Canada found that genres, even in the most conservative contexts like the legal realm, evolve due to negotiations of their meanings and purposes – a non-linear process marked by tension among the stakeholders involved.[22]

Because most work in the recordkeeping space has involved organizational records, the rhetorical uses of records and recordkeeping in other domains are still poorly understood.[23] However, there is a cognate field known as personal digital archiving (PDA), where the emphasis lies on the organization, classification, and preservation of personal digital records.[24]

In terms of methodology, studies about PDA can be divided into meta-reviews, qualitative studies, and quantitative studies. The meta-reviews summarize the state of the field, describing the challenges to enhancing personal archiving practices and opportunities for future research.[25] Qualitative studies have primarily relied on interviews to understand the archiving strategies and challenges faced by individuals who engage in PDA.[26] Finally, studies using quantitative approaches have relied on online surveys to understand broader recordkeeping patterns across entire populations,[27] such as information science students[28] or public library users.[29]

People’s motivations to engage in PDA suggest a connection with a rhetorical view of personal records. Indeed, people engage in PDA to serve various purposes – such as defining the self, fulfilling a sense of responsibility, reacting to available tools and knowledge, attending to personal sentimentality – and by accident.[30] However, records in PDA are often viewed as discrete entities and by-products of human activity. To take this arhetorical view is to risk losing the historicity of how a record gradually evolved into its current shape and the connection between its context and its content.

3.2 Recordkeeping and Military Pensions

Extensive research about the recordkeeping practices of the US military has been conducted.[31] Since the late 1990s, a portion of this research has been devoted to streamlining compensation claims for service-related disabilities, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[32] These efforts have high stakes for veterans who have been required to produce service records to access the benefits earned through their service.

The link between documentary proof of military service and access to benefits has been a recurrent theme in US history that began with the republic itself. Initially, benefits were awarded unequally. After the Revolutionary War, for instance, pensions were initially awarded only to officers. Later, in 1828, an act of Congress granted pensions to all surviving veterans.[33] In the case of the Civil War, pensions were initially awarded only to veterans with service- related disabilities or those in extreme poverty. However, the system gradually expanded. Between 1862 and 1912, Congress and the executive branch enacted a series of policies that created, in effect, a quasi-universal pension system.[34] Just like veterans today, Civil War veterans were required to provide proof of their service to access their benefits. Originally, the pension system gave pre-eminence to documentary evidence while allowing testimonials for contextualization. The US relaxed these requirements over time. By 1890, Congress passed the Dependent Pension Act, which made anyone who had served 90 days or more automatically eligible for benefits.[35]

The Civil War was also when the government began large-scale documentation of military operations.[36] This occurred because the Civil War coincided with an accelerated industrial evolution whereby the paper industry switched from the centuries-old practice of producing paper with cotton and linen rags to a new, faster process based on wood pulp.[37] The new process enabled a rapid expansion of the paper industry, which the Union army capitalized upon to document its operations. In fact, by the end of the war, the compiled documents of the Union army were so voluminous that they filled several buildings, and sorting them out took dozens of full-time personnel several years.[38] Partly because of this extensive paper trail, it was possible for the Union army to manage massive provisions of weaponry and other supplies[39] and to account for Union casualties during the war.[40]

3.3 Institutional Management of Military Records

In tandem with the recordkeeping practices, the institutions in charge of awarding veterans’ benefits have also evolved. Between 1828 and 1849, a commission managed veteran pensions. This commission was originally part of the Department of the Treasury. In 1833, the Department of War assumed the commission, and in 1849, it moved it to the newly created Department of the Interior as the renamed Bureau of Pensions. Finally, in 1930, the Bureau of Pensions merged with other government agencies providing services to veterans to create the Veterans Administration, which exists to this day.[41]

Each federal government agency was responsible for managing its own records for almost two centuries. For instance, the Bureau of Pensions, which relied on military service records to corroborate claims, was an agency under the Department of War. However, in 1935, the government began concentrating its collections in a single institution: the National Archives.[42] In 1949, the National Archives was renamed the National Archives and Records Service (NARS) and placed under the wing of the General Services Administration (GSA). A new dependency added to NARS in 1966, the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC), is responsible for all career records of civilian and military personnel.[43] Finally, in 1984, the NARS was reconstituted as an agency independent from the GSA and renamed the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).[44]

3.4 Information Flows

If the wider availability of paper in the second half of the 19th century created an opportunity to expand the scale of recordkeeping within the Armed Forces, a new wave of expansion has been enabled since the dawn of the digital age. The scale of records within the Armed Forces is so massive today that keeping track of it is considered a big data enterprise.[45] This enterprise has had significant setbacks, the most significant being the 1973 fire.

In 1973, a fire in an NPRC facility destroyed 80 percent of 1912–1960 Army records and 75 percent of 1947–1964 Air Force records.[46] Veterans who served in any branches of the Armed Forces during these periods can still obtain certificates from NPRC of their service. However, the agency website explains that such a certification must precede archival reconstruction of the person’s service through alternative records such as orders of deployment or recruitment records. The process can take at least six months.[47] Unlike in the 1960s and 1970s, when the NPRC concentrated most military records in one facility, the processing of requests for military records is now distributed across 12 physical locations and two self-service websites, and the routing of claims depends on branch and service dates.[48]

However, there is plenty of information about military operations that cannot be found in NPRC holdings. Information in the US military is not limited to official, written records about regular operations. Instead, information also “travels outside of traditional hierarchical systems in the military. Officers and enlisted personnel use a mix of informal and formal environments to best support their work.”[49] Furthermore, as we will note later in this article, the information generated by active service members is not limited to their work duties but also includes personal documents such as photographs, personal journals, and email exchanges with friends and family.

Not only is there information about military operations that never makes it into the official record, but there is also some evidence that some records about veterans’ service can be unreliable or at least incomplete. For example, a study found that veterans’ records often under-report PTSD for people with mild- to medium-level symptoms.[50] In addition, there is a burgeoning area of research devoted to understanding the misrepresentation of health issues among veterans to access benefits.[51] At the same time, there have been efforts to revamp the assessment criteria that military health care providers must follow in evaluating veterans’ claims for disability benefits.[52] The result is that some veterans find themselves hard pressed to obtain benefits for service-related health conditions for which records may be non-existent and may have difficulty meeting the threshold of the health examinations.

The consequences of these policies and of the gaps in organizational records have high stakes for veterans. Those who did not keep copies of their service records risk being denied service by Veterans Affairs (VA). In the absence of a robust governmental system to keep track of veterans’ records, active service members are encouraged to start managing their own records early in their service.[53] While the military trains enlisted personnel and commissioned officers on their official recordkeeping functions, personal recordkeeping skills are not part of the official curriculum. Neither does the military include personal recordkeeping as part of its regular, ongoing educational series for enlisted personnel or in required workshops prior to discharge. Considering this complex context, we ask, How do military veterans in the US document their time of service? What challenges and concerns do veterans face while engaging in their recordkeeping practices? What are the rhetorical uses of recordkeeping practices? These questions are important because their answers suggest opportunities to improve veterans’ recordkeeping practices. By proving that LMBs serve rhetorical functions, we also aim to extend the RSG approach, already used in the organizational context, into the personal records space.

4. Methodology

This article builds on a larger project conducted with active service members and veterans known as the Virtual Footlocker Project (VFP). The overarching goal of the VFP is to develop solutions for capturing and preserving the personal communication and documentary record of the modern soldier. The VFP is funded through an Institute of Museum and Library Services grant.

We collected data between September 2019 and August 2020 through a survey and a series of focus groups. Participants were recruited through direct and indirect emails, utilizing contacts at veteran service organizations and university veteran student organizations, and through social media advertising on Facebook. Finally, we contacted military bases across the different branches of the Armed Forces, including the Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marines, and Navy.[54]

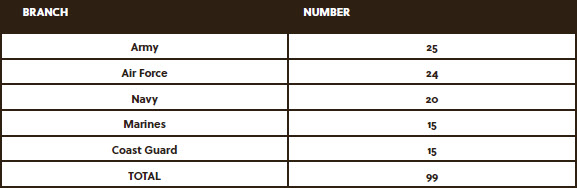

Interested participants completed an initial screening questionnaire via the Qualtrics survey platform. In this survey, participants specified demographic information, such as age, gender, and race, and contextual information about their service, such as their branch, time in service, rank, and duty station. In total, 222 people responded to the survey. Of these, 99 attended focus groups, the majority of which included both veterans and active-duty personnel. Four focus groups were dedicated to each service branch – two for enlisted personnel and two for officers – and an additional two focus groups included only female participants. As with the groups for branches of the Armed Forces, one female-only focus group was for enlisted women and the second was for officers. We recruited members of different branches for these focus groups, which were unlike the other 20 focus groups where all participants belonged to the same branch. The average number of participants per focus group was four and one-half, and the mean was four. The session with the most participants had nine people, whereas the one with the lowest attendance had only two.

table 1

Participants by branch

The focus groups met for between 60 and 90 minutes. Typically, sessions with more participants lasted longer than the rest. However, the dynamics of each group also influenced the duration of the sessions as some groups elaborated more, whereas others were more succinct with their answers. Each participant received $150 in compensation for their time. Sessions were conducted via Zoom and recorded with participants’ permission. Focus group recordings were transcribed, anonymized, and then analyzed using an open-coding strategy through NVivo.

We analyzed our data using both inductive and deductive processes. We applied attribute, descriptive, process, in-vivo, and value codes for our inductive coding. The goal of these codes was to characterize participants’ archival practices. For our deductive coding, we focused on the concept of rhetorical use as defined by Trace, understanding uses as the ways the practices of record creation and recordkeeping were mobilized for persuasive purposes.[55] As outlined in grounded theory research/process guidelines, we undertook multiple rounds of coding through the data until we could no longer identify new themes.[56]

5. Results

Out of 99 participants, 43 explicitly named their collections of service records, using a variety of terms – love-me wall, love-me book, and love-me binder – though the latter was the most common. The remaining participants attested to keeping collections of service records in folders or other media.

5.1 Love-Me Binders

Love-me binders (LMBs) hold a variety of records; the most commonly mentioned by our participants were DD214 forms,[57] permanent change of station (PCS)[58] orders, medical records, course certificates, letters of appreciation, awards, and documents relating to promotions in rank.

Participants stressed that their decisions to keep their records were influenced by their leaders during their onboarding process. P11[59] illustrates this point: “That’s kind of the way we made sure we had those documents, and that was something that I was always taught, you know, from my NCO coming in way back in 1987. Keep hard copies of your stuff.” Some senior officers also reported feeling responsible for incentivizing the practice of LMBs among newer members:

So, for me, it was leadership telling the younger marines. So, when I would have marines come into my unit, I’d be like, “Hey, if you get a light-duty chit or anything, put that in your love-me binder or create a medical binder for yourself because you cannot depend on everyone else to do it for you, and that will be your proof if you ever have an issue and they lose your medical record, with the VA, that you were actually seen and put on light duty for an issue.”

P29

Participants held their LMBs in different locations. Some kept them in binders or folders, which were in turn placed in boxes and then in locations inside their houses, such as their closets or basements. A few participants expressed certainty that their LMBs were “somewhere” inside their houses but could not remember the locations.

While some scattered records between the cloud and local devices, others kept local copies in digital hard drives and uploaded segments of this data to the cloud. However, others relied solely on the cloud as their means of storage. This finding is consistent with the literature on PDA, which indicates that people’s long-term preservation practices for personal records are inconsistent.[60]

Another critical observation, consistent with prior studies in PDA and relating to the conflict between keeping backups of digital information and long-term preservation,[61] is illustrated in this participant’s comment:

Same thing with my medical record, which is super important for all of you because if you’re still in, that’s the one thing you need to keep in order, and you need to keep photocopying it and write down every little thing, and make sure you go to the doctors for everything. I’m serious about that, for the V.A. piece. So, I actually have two copies of my medical record. Both of those are in binders and in sheet protectors. One’s in my garage, one of them’s in my house. I do not have an electronic version of it, although I can actually download that. I can get that from the V.A. as well because you do submit it through there.

P60

Veterans indicated that they revisit their records now and then, but none mentioned actively transferring data across devices over time or updating file formats. These two omissions are significant because the lifespan of a hard drive varies from just one to five years.[62] The implication is that records kept in drives are at risk of being lost in a few years unless veterans actively migrate them to new devices, a practice that none mentioned. Furthermore, file formats may become deprecated over time, and the programs necessary to operate said files may disappear or no longer be updated. Therefore, even a person who still has the installation software for a program may be unable to run it because the software may become incompatible with future versions of the operating system. In fact, there is no guarantee that the operating systems dominant in the future will be compatible with the main applications currently in vogue, such as Microsoft Office. Alternatively, a person may have a current program file in a deprecated file format (e.g., a Word document with a .doc extension as opposed to .docx), potentially rendering the data in that file inaccessible. Veterans seem unaware of these stakes in updating their digital information file formats.

Participants who were still active in service expressed concern about keeping their LMBs close to them during military moves. The account of P41 serves as an example:

The digital stuff, I had primarily on thumb drives, and I had like this huge terabyte when they were like ginormous. Now you can get nice sized ones that are small. But I lost that one in a move, and that one hurt my heart. I was like, no. I’ve lost everything. Our movies we watched, the random billions of songs you downloaded just to keep your mind occupied that we used to play in our backgrounds, all of that got lost in the move, and I was devastated. I think I dropped a few cellular tears for that.

P41 notices that service members are often required to relocate to new duty stations or deploy for temporary duty. In that mayhem of switching places, people may lose their belongings and their information. These losses may happen either because devices become damaged during moves or never arrive at their destinations. As P41’s story highlights, veterans experience this information loss as an emotional toll, and this toll is indicative of the emotional value that veterans place on their personal records. This risk of information loss became further compounded by the distrust that veterans expressed toward the moving process, as further explained by P55:

Every PCS move, there has been things that I bring that I don’t trust anybody else to pack. Important family documents, the photographs always go with me. There’s a real risk of losing those things. Maybe not so much now because you’ve got better ways to keep track of people through Facebook and whatnot.

This comment highlights veterans’ assumption that moves entail a high risk of having their property and information lost or damaged. Like P55, other veterans cope with this risk by taking their most valued possessions in their vehicles or luggage. P55’s comment also indicates that veterans’ personal records rank highly among their valued possessions, such as photos and work documents.

Aside from worrying about losses due to moves, participants also expressed concerns about losing information about their time of service, for example, by simply not documenting it in the first place, misplacing their records, or losing access to their information. In fact, concerns about losing access to digital information were especially valid for records stored in the cloud or on devices that stopped working:

I moved a total of six times in two years, so it was kind of a pain to have to move stuff. So, after the first two times, I just kind of packed everything into my Google Drive. I got rid of all physical evidence, essentially, of pictures and awards and letters and things like that, and just scanned everything online and it’s super convenient. I’m afraid though that I will one day just lose access to it, and it’s just all gone though. So, it’s kind of one of those things, but yeah.

P73

P73’s story illuminates how some veterans turn to cloud services as a convenient solution to alleviate the anxiety around their moves. Even then, veterans are aware that they might lose access because they might forget their passwords, the company offering the specific cloud service might go bankrupt, or they might stop logging in to the service for so long that their accounts and therefore their information could eventually be deleted.

5.2 Rhetorical Uses

Veterans reported three rhetorical uses for their records: (1) to secure promotions while still in service, (2) to demonstrate their eligibility for benefits, and (3) to leave a legacy for their loved ones. In terms of securing promotions, participants explained that they had to undergo a review of their qualifications, a process for which records were instrumental:

So, when it came time to reconcile your points for promotion or whatever, those are the things that you would bring into personnel management – which I don’t think exists anymore. But we were taught to keep those hard copies. If you didn’t, then you were in trouble when it came time for promotions and things of that nature.

P11

P11’s story highlights the point-based promotion system utilized by the Office of Personnel Management in the Air Force. Here, the Air Force used service members’ records to tally points until they met the threshold for the promotions. Not having records, in this context, would have stalled their chances of career development during service.

Similarly, once service members retire from service, they eventually need access to benefits, most commonly health care, through the VA. To request registration into a health insurance program, the staff at the VA first verify the records on file for each applicant. Three of our participants reported running into situations where the VA had no records about them – at which point their LMBs became lifelines:

The daily journal that I kept, especially when I was deployed, I use that to help when I was going through the process of getting a certain percentage based on different things that were wrong with me from being deployed twice and the regular day-to-day in the Army. I was able to go back to exact dates and times when certain events happened, which aided in that process because on the flip side, the Army didn’t keep very good records of what I did and didn’t do and what went on.

P06

After P06’s service ended, the documentation in his love-me binder paid off because his records allowed him to access health benefits to treat a service- related disability. However, this was not the case for P53, who similarly found that there were no records about him on file at the VA. Five years into retirement, he has unfortunately not been able to get copies of his records. P53 has gone through several boxes of his personal stuff at home and has regularly contacted the Coast Guard to find copies of his records. His search remained ongoing at the time of our study. Finally, others who had not documented found more success by contacting NARA and obtaining copies of their files that way:

So, I actually had to request it from archives. My last copy was a year before I retired. I do have my DD214, and all of my qual letters, and those are all in a binder in sheet protectors, and I also did the exact same thing, they always went everywhere I went, and I never mailed them anywhere. They are currently in my garage on a shelf. I know exactly which shelf those are on.

P60

Finally, veterans rely on LMBs as documentary proof of an intangible heritage that some veterans hope to pass down to their children:

I’d like to keep just so when my son gets older, he can see it and be like, “Wow, my mom’s a badass.” I mean, I’m gonna remind him as long as I live that I’m a badass but just so he can see all the stuff we have. My husband’s grandpa, he still has stuff from when he was in, and he actually went through it with him. . . . So, it’s just kinda nice to go back and look and see what you’ve been through and all the experiences you had while you served.

P24

P24’s story underscores the pride that veterans place on their service. Part of the veterans’ quest to give meaning to their lives is a desire to pass on the memories of their time of service as a legacy to their children. Love-me binders are thus an essential tool for veterans to realize this meaning-making goal.

6. Discussion

Like people who served during the Civil War, active service members today must assume individual responsibility to document their own service. The rhetorical practice of substantiating eligibility for benefits through personally kept records is as old as the institution of the US Armed Forces. However, the forms and context of personal military records evolve. At the time of our study, we found that LMBs represent a genre of records that supported the centuries-old rhetorical function of demonstrating eligibility for benefits as well as those of assisting active service members in supporting applications for promotions in rank and building a symbolic heritage for veterans’ families.

The LMB is a hybrid genre. While prior RSG studies have focused on workplace records, LMBs exist within both the workplace and the home.[63] LMBs are first created in the workplace – namely, within military bases and training camps. Yet once a service member retires, their records move to the home, where LMBs continue to serve their rhetorical purposes. As a genre, the LMB is open to a multiplicity of specific records, such as discharge papers and medical forms. However, the context of the genre is evolving. With the ubiquity of computation and the Internet, LMBs no longer exist in just physical form. Instead, LMBs exist as distributed collections of records with varying breadth and differing degrees of intentional appraisal and management.

The genre of LMBs is made possible due to a milieu within the Armed Forces whereby officers and peers encourage recruits to keep track of their records. In some instances, individual officers within a base or a unit may insist on the importance of recordkeeping beyond the training ground. Ultimately, it is up to the individual service member to heed the advice. Some find, later in their career, or even in retirement, that having copies of their own records means the difference between having their health care needs met or not.

Because the milieu that enables LMBs is not part of an official policy of the Armed Forces, the degree of incentive that service members receive varies widely. Thus, we suggest that service members begin to engage in creating and managing LMBs from early in their service. For most military personnel, waiting to start to organize and preserve their records until they file for discharge may be too late. Their units may no longer have copies of their records but may have lost, misplaced, or even discarded them. While the overwhelming majority of participants did keep their records or had access to them through NARA, the consequences reported by the few who did not are enough to call attention to the importance of veterans’ personal recordkeeping practices.

Future work should consider opportunities to support veterans in creating and maintaining LMBs. This assertion is in tune with a prior study about the evolution of genres, which demonstrated that genres could evolve through intentional human action even in the most conservative domains, such as that of legal patents.[64] Drawing on the recognition that text and content mutually constitute a genre, we call on an intervention that alters the context for the benefit of veterans. Specifically, we call for an intervention from specialists in records management to train veterans on best practices in recordkeeping. By transforming the context of LMBs from an informal milieu to a formal policy and integral part of the training of the Armed Forces, we hope to support veterans to achieve their rhetorical uses of LMBs: (1) substantiating their applications for promotion in rank, (2) supporting their access to benefits such as health care, and (3) creating a symbolic legacy for themselves and their families. We believe that such a change in the context of LMBs is bound also to alter their content, and we also hope that future work looks at this evolution. Specifically, we believe that future studies should focus on curriculum proposals for such an intervention and the impact of its deployment on the LMB genre.

This research agenda matters for veterans whose personal collections are at stake, and supporting them is an act of justice. Strengthening veterans’ recordkeeping practices is a means of honouring their service. With the advent of the all-volunteer armed service in 1973, the US military is staffed by individuals who willingly agree to serve the nation at the risk of their own lives. Therefore, helping veterans keep track of their experiences is a way of honouring their vocation. This type of honour is far more meaningful than public displays of appreciation featuring the phrase “thank you for your service.” Emerging work suggests that most veterans find such public displays emotionally taxing and insincere.[65] By contrast, supporting veterans in documenting and preserving their own service experiences constitutes an archivally oriented, emotionally meaningful, and needs-based intervention to express gratitude to them. Strengthening veterans’ practices of creating and preserving records is just one among many types of support that veterans need, but it is still a valuable contribution.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Allan A. Martell is a postdoctoral researcher at the School of Library and Information Science at Louisiana State University, where he collaborates with the Virtual Footlocker Project (VFP). His research centres on social memories of violence such as civil wars, genocides, or dictatorships. In his work, Martell traces the interactions of youths with historical representations of violence in cultural heritage organizations – such as memorials, museum exhibitions, and archival records – and how the design decisions around such representations shape these interactions. He received an MS in digital media from the Georgia Institute of Technology and a PhD in information from the University of Michigan.

Edward Benoit III is Associate Director and Associate Professor in the School of Library and Information Science at Louisiana State University. He is the coordinator of the archival studies and cultural heritage resource management programs. He received an MA in history and MLIS and PhD degrees in information studies from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. His research focuses on participatory and community archives, non-traditional archival materials, and archival education. He is the founder and director of the Virtual Footlocker Project, which examines the personal archiving habits of the 21st-century soldier in an effort to develop new digital capture and preservation technologies to support their needs.

Gillian A. Brownlee is a student of the Doctor of Design in Cultural Preservation program at Louisiana State University. In her research, Brownlee explores the potential for collaboration among memory institutions. Formerly a library assistant, Brownlee holds a BA in anthropology and linguistics from Louisiana State University and an MA in interdisciplinary studies from Texas Tech University.

Notes

-

[1]

Robert G. Moering, “Military Service Records: Searching for the Truth,” Psychological Injury and Law 4, no. 3–4 (2011): 217–34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-011-9114-3.

-

[2]

Heather Soyka and Eliot Wilczek, “Documenting the American Military Experience in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars,” American Archivist 77, no. 1 (2014): 175–200.

-

[3]

Department of the Army, Guide to Recordkeeping in the Army (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2008).

-

[4]

Soyka and Wilczek, “Documenting the American Military Experience in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars.”

-

[5]

Foscarini, “Record as Social Action.”

-

[6]

T.D. Wilson, “Human Information Behavior,” Informing Science 3, no. 2 (2000): 49–55, https://doi.org/10.28945/576.

-

[7]

Amanda Spink and Charles Cole, “Human Information Behavior: Integrating Diverse Approaches and Information Use,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57, no. 1 (2006): 25–35, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20249.

-

[8]

Paul Solomon, “Discovering Information Behavior in Sense Making. III. The Person,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 48, no. 12 (1997): 1127–38, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199712)48:12<1127::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-W.

-

[9]

Text here is broadly defined. For instance, a film, a song, and a portrait are all forms of text.

-

[10]

Fiorella Foscarini, “A Genre-Based Investigation of Workplace Communities,” Archivaria 78 (Fall 2014): 1–24.

-

[11]

Ciaran B. Trace, “What Is Recorded Is Never Simply ‘What Happened’: Record Keeping in Modern Organizational Culture,” Archival Science 2, no. 1–2 (2002): 137–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435634; Foscarini, “Record as Social Action.”

-

[12]

Jack Andersen, “The Concept of Genre in Information Studies,” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 42, no. 1 (2008): 339–67, https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2008.1440420115.

-

[13]

Andersen, 339–67; Foscarini, “A Genre-Based Investigation of Workplace Communities”; Ciaran B. Trace, “Information Creation and the Notion of Membership,” Journal of Documentation 63, no. 1 (2007): 142–63, https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410710723920.

-

[14]

Ciaran B. Trace, “Information in Everyday Life: Boys’ and Girls’ Agricultural Clubs as Sponsors of Literacy, 1900–1920,” Information and Culture 49, no. 3 (2014): 265–93, https://doi.org/10.1353/lac.2014.0016.

-

[15]

Steve Wright, “Genre, Co-Research and Document Work: The FIAT Workers’ Enquiry of 1960–1961,” Archival Science 18, no. 4 (2018): 291–312, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-018-9299-2.

-

[16]

Trace, “Information Creation and the Notion of Membership.”

-

[17]

Trace, “Information in Everyday Life”; Fiorella Foscarini, “The Patent Genre: Between Stability and Change,” Archivaria 87 (Spring 2019): 36–67.

-

[18]

Christopher William Colwell, “Records Are Practices, Not Artefacts: An Exploration of Recordkeeping in the Australian Government in the Age of Digital Transition and Digital Continuity” (PhD diss., University of Technology Sydney, 2020); Wright, “Genre, Co-Research and Document Work.”

-

[19]

Gillian Oliver, Yunhyong Kim, and Seamus Ross, “Documentary Genre and Digital Recordkeeping: Red Herring or a Way Forward?” Archival Science 8, no. 4 (2008): 295–305, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-009-9090-5.

-

[20]

Foscarini, “Record as Social Action”; Foscarini, “A Genre-Based Investigation of Workplace Communities”; Andersen, “The Concept of Genre in Information Studies.”

-

[21]

Foscarini, “A Genre-Based Investigation of Workplace Communities”; Andersen, “The Concept of Genre in Information Studies”; Oliver, Kim, and Ross, “Documentary Genre and Digital Recordkeeping”; Fiorella Foscarini, Yunhyong Kim, Christopher A. Lee, Alexander Mehler, Gillian Oliver, and Seamus Ross, “On the Notion of Genre in Digital Preservation,” in Automation in Digital Preservation, ed. Jean-Pierre Chanod, Milena Dobreva, Andreas Rauber, and Seamus Ross (Dagstuhl, DE: Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum, 2010), 1–16, https://doi.org/10.4230/DagSemProc.10291.12.

-

[22]

Foscarini, “The Patent Genre,” 36.

-

[23]

Gillian Oliver, “Managing Records in Current Recordkeeping Environments,” in Currents of Archival Thinking, 2nd ed., ed. Heather McNeil and Terry Eastwood (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2017), 83–106.

-

[24]

Melody Condron, “Identifying Individual and Institutional Motivations in Personal Digital Archiving,” Preservation, Digital Technology and Culture 48, no. 1 (2019): 28–37, https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2018-0032; Catherine Hobbs, “Reenvisioning the Personal: Reframing Traces of Individual Life,” in Currents of Archival Thinking, ed. Terry Eastwood and Heather MacNeil (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2010), 213–41.

-

[25]

Rachel King, “Personal Digital Archiving for Journalists: A ‘Private’ Solution to a Public Problem,” Library Hi Tech 36, no. 4 (2018): 573–82, https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-09-2017-0184; Howard Besser, “Personal Digital Archiving: Issues for Libraries and a Summary of the PDA Conference” (paper presented at IFLA World Library and Information Congress 2015, Cape Town, ZA, August 2015), 1–4, https://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/1218/1/197-besser -en.pdf; Condron, “Identifying Individual and Institutional Motivations in Personal Digital Archiving”; Irfan Ali and Nosheen Fatima Warraich, “Modeling the Process of Personal Digital Archiving through Ubiquitous and Desktop Devices: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 54, no. 1 (2021): 132–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000621996410; Clifford A. Lynch, “The Future of Personal Digital Archiving: Defining the Research Agendas,” in Personal Archiving: Preserving Our Digital Heritage, ed. Donald T. Hawkins (Medford, NJ: Information Today, 2013), 259–78, http://books.infotoday.com/books/Personal-Archiving.shtml.

-

[26]

Andrea J. Copeland, “Analysis of Public Library Users’ Digital Preservation Practices,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 62, no. 7 (2011): 1288–1300, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21553; Peter Williams, Jeremy Leighton John, and Ian Rowland, “The Personal Curation of Digital Objects: A Lifecycle Approach,” Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives 61, no. 4 (2009): 340–63, https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910973767; Sheenagh Pietrobruno, “YouTube and the Social Archiving of Intangible Heritage,” New Media and Society 15, no. 8 (2013): 1259–76, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812469598.

-

[27]

Donghee Sinn, Sujin Kim, and Sue Yeon Syn, “Personal Digital Archiving: Influencing Factors and Challenges to Practices,” Library Hi Tech 35, no. 2 (2017): 222–39, https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-09-2016-0103; Donghee Sinn, “Personal Digital Archiving: Strategies, Challenges, and Affecting Factors from a Quantitative Perspective” (paper presented at Archival Education and Research Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, July 15, 2014), http://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/dis_fac_scholar ; Yue Zhao, Xian’e Duan, and Haijuan Yang, “Postgraduates’ Personal Digital Archiving Practices in China: Problems and Strategies,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 45, no. 5 (2019): 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.06.002; Hana Marčetić, “Exploring the Methods and Practises of Personal Digital Information Archiving among the Student Population,” ProInflow 7, no. 1 (2015): 29–40, https://doi.org/10.5817/proin2015-1-4.

-

[28]

Marčetić, “Exploring the Methods and Practises of Personal Digital Information Archiving among the Student Population”; Zhao, Duan, and Yang, “Postgraduates’ Personal Digital Archiving Practices in China.”

-

[29]

Copeland, “Analysis of Public Library Users’ Digital Preservation Practices.”

-

[30]

Condron, “Identifying Individual and Institutional Motivations in Personal Digital Archiving.”

-

[31]

For example, Moering, “Military Service Records”; Soyka and Wilczek, “Documenting the American Military Experience in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars”; Lois M. Joellenbeck, “Medical Surveillance and Other Strategies to Protect the Health of Deployed U.S. Forces: Revisiting after 10 Years,” Military Medicine 176, no. 7 (2011): 64–70, https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-11-00081; B. Christopher Frueh, Jon D. Elhai, Anouk L. Grubaugh, Jeannine Monnier, Todd B. Kashdan, Julie A. Sauvageot, Mark B. Hamner, B.G. Burkett, and George W. Arana, “Documented Combat Exposure of US Veterans Seeking Treatment for Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” British Journal of Psychiatry 186, no. 6 (2005): 467–72, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.6.467.

-

[32]

Frueh et al., “Documented Combat Exposure of US Veterans Seeking Treatment for Combat-Related PostTraumatic Stress Disorder”; Richard J. McNally and B. Christopher Frueh, “Why Are Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans Seeking PTSD Disability Compensation at Unprecedented Rates?” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 27, no. 5 (2013): 520–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.002; James Knoll and Phillip J. Resnick, “The Detection of Malingered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 29, no. 3 (2006): 629–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2006.04.001; Brian P. Marx, James C. Jackson, Paula P. Schnurr, Maureen Murdoch, Nina A. Sayer, Terence M. Keane, Matthew J. Friedman, Robert A. Greevy, Richard R. Owen, Patricia L. Sinnott, and Theodore Speroff, “The Reality of Malingered PTSD Among Veterans: Reply to McNally and Frueh (2012),” Journal of Traumatic Stress 25, no. 4 (2012): 457–60, https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21714; Richard J. McNally and B. Christopher Frueh, “Why We Should Worry About Malingering in the VA System: Comment on Jackson et al. (2011),” Journal of Traumatic Stress 25, no. 4 (2012): 454–56, https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21713.

-

[33]

Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller, Union Soldiers and the Northern Home Front: Wartime Experiences, Postwar Adjustments (New York: Fordham University Press, 2002).

-

[34]

The key difference between the pension system for Revolutionary War veterans and that for Civil War veterans lies in the large scale of the latter. The Civil War was the first military conflict that resulted in a massive mobilization of men of fighting age. In fact, it is estimated that the Union army had mobilized 35 percent of Northern men between 15 and 44 years by 1865. In fact, the scale of the mobilization was directly correlated with the large scale of the pension system when compared to previous wars. Theda Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674717664.

-

[35]

Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers.

-

[36]

Alan C. Aimone and Barbara A. Aimone, A User’s Guide to the Official Records of the American Civil War (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1993).

-

[37]

Lyman Horace Weeks, History of Paper Manufacturing in the United States, 1690–1916 (New York: Lockwood Trade Journal Company, 1916).

-

[38]

Aimone and Aimone, A User’s Guide to the Official Records of the American Civil War.

-

[39]

Darwin King and Carl Case, “Duties of Accounting Clerks during the Civil War and Their Influence on Current Accounting Practices,” Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 8, no. 3 (2004): 61.

-

[40]

Drew Gilpin Faust, “‘Numbers on Top of Numbers’: Counting the Civil War Dead,” Journal of Military History 70, no. 4 (2006): 995–1010, https://doi.org/10.1353/jmh.2006.0239.

-

[41]

Cimbala and Miller, Union Soldiers and the Northern Home Front.

-

[42]

The National Archives had a years-long conception. The land where the future archival institution would be housed was purchased in 1903, but Congress did not formally create the agency until 1923 nor order the construction of the building until 1926. The building took a couple of years to complete, and its original 132 staff were not hired until 1935. A critical factor in the founding of the National Archives was the American Legion, which advocated for symbolic and material compensation for veterans of the Great War in the interwar period. Robert M. Warner, “The National Archives at Fifty,” Midwestern Archivist 10, no. 1 (1985): 25–32.

-

[43]

Walter W. Stender and Evans Walker, “The National Personnel Records Center Fire: A Study in Disaster,” American Archivist 37, no. 4 (1974): 521–49.

-

[44]

Warner, “The National Archives at Fifty.”

-

[45]

Loryana L. Vie, Lawrence M. Scheier, Paul B. Lester, Tiffany E. Ho, Darwin R. Labarthe, and Martin E.P. Seligman, “The U.S. Army Person-Event Data Environment: A Military–Civilian Big Data Enterprise,” Big Data 3, no. 2 (2015): 67–79, https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2014.0055.

-

[46]

The 1973 fire was actually the second time that the military suffered a massive loss of records to fire. The first such incident occurred in 1800 at the Department of War. In this incident, documents from the first 10 years of the union were lost. Warner, “The National Archives at Fifty”; Stender and Walker, “The National Personnel Records Center Fire.”

Other governmental agencies have similarly lost records to fires, but those stories fall out of the scope of this article. Stender and Walker, “The National Personnel Records Center Fire.”

-

[47]

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, “Access to Official Military Personnel Files (OMPF) – Veterans and Next-of-Kin,” National Archives, National Personnel Records Center, accessed July 28, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/personnel-records-center/ompf-access.

-

[48]

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, “Request Military Personnel Records Using Standard Form 180,” National Archives, Veterans’ Service Records, accessed July 28, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/veterans/military-service-records/standard-form-180.html.

-

[49]

Soyka and Wilczek, “Documenting the American Military Experience in the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars,” 184.

-

[50]

Maria A. Morgan, Marija Spanovic Kelber, Kevin O’Gallagher, Xian Liu, Daniel P. Evatt, and Bradley E. Belsher, “Discrepancies in Diagnostic Records of Military Service Members with Self-Reported PTSD: Healthcare Use and Longitudinal Symptom Outcomes,” General Hospital Psychiatry 58 (May–June 2019): 33–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.02.006.

-

[51]

Moering, “Military Service Records”; Frueh et al., “Documented Combat Exposure of US Veterans Seeking Treatment for Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder”; McNally and Frueh, “Why Are Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans Seeking PTSD Disability Compensation at Unprecedented Rates?”; Knoll and Resnick, “The Detection of Malingered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder”; McNally and Frueh, “Why We Should Worry About Malingering in the VA System.”

-

[52]

Knoll and Resnick, “The Detection of Malingered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder”; James C. Jackson, Patricia L. Sinnott, Brian P. Marx, Maureen Murdoch, Nina A. Sayer, JoAnn M. Alvarez, Robert A. Greevy, Paula P. Schnurr, Matthew J. Friedman, Andrea C. Shane, Richard R. Owen, Terence M. Keane, and Theodore Speroff, “Variation in Practices and Attitudes of Clinicians Assessing PTSD-Related Disability Among Veterans,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 24, no. 5 (2011): 609–13, https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20688.

-

[53]

Chuck Holmes, “The Army I Love Me Book or Binder,” Part-Time-Commander.com (blog), accessed April 30, 2021, https://www.part-time-commander.com/the-army-i-love-me-book-or-binder/.

-

[54]

As the Space Force did not exist until late 2019, its members were included as part of their previous military branches.

-

[55]

Trace, “What Is Recorded Is Never Simply ‘What Happened.’”

-

[56]

Juliet M. Corbin and Anselm Strauss, “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria,” Qualitative Sociology 13, no. 1 (1990): 3–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593; Johnny Saldaña, The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed. (Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016); Kathy Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis (London: Sage Publications, 2006).

-

[57]

DD214 forms, commonly referred to as discharge papers, are documents issued by the Department of Defense (DoD) to retiring veterans. These forms are important because they contain information that veterans can use to apply for benefits, retirement employment, and membership in veterans’ organizations. Examples of the information this form contains include the veterans’ conditions of discharge – honourable, general, other than honourable, dishounorable, and bad conduct – military job specialties, and military education. The DoD began issuing DD2014 forms on January 1, 1950. Prior to that, each service branch issued its own forms. US Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, “Welcome to DD214!” https://www.dd214.us/.

-

[58]

Permanent change of station (PCS) is the military term designating a military move.

-

[59]

Participants are identified here by number to ensure anonymity.

-

[60]

Condron, “Identifying Individual and Institutional Motivations in Personal Digital Archiving”; Sinn, “Personal Digital Archiving”; Hobbs, “Reenvisioning the Personal”; Catherine C. Marshall, Sara Bly, and Francoise Brun-Cottan, “The Long Term Fate of Our Digital Belongings: Toward a Service Model for Personal Archives,” in Proceedings of IS&T Archiving, May 23–26 (Ottawa, ON: Society for Imaging Science and Technology, 2006), 25–30.

-

[61]

Sarah Kim, “Landscape of Personal Digital Archiving Activities and Research,” in Hawkins, Personal Archiving, 153–86.

-

[62]

Katlin Seagraves, “Digitization and Personal Digital Archiving,” Library Technology Reports 56, no. 5 (2020): 22–28.

-

[63]

Gillian Oliver and Fiorella Foscarini, “Corporate Recordkeeping: New Challenges for Digital Preservation,” in IPress 2011: 8th International Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects, ed. José Borbinha, Adam Jatowt, Schubert Foo, Shigeo Sugimoto, Christopher Khoo, and Raju Buddharaju (Singapore: National Library Board Singapore and Nanyang Technology University, 2011), 260–61; Foscarini, “A Genre-Based Investigation of Workplace Communities”; Trace, “Information in Everyday Life.”

-

[64]

Foscarini, “The Patent Genre.”

-

[65]

Sidra Montgomery, “The Emotion Work of ‘Thank You for Your Service,’” Veteran Scholars, March 1, 2017, https://veteranscholars.com/2017/03/01/the-emotion-work-of-thank-you-for-your-service/.

List of tables

table 1

Participants by branch