Abstracts

Abstract

Thousands of child Holocaust survivors arrived in Montreal, Quebec, between 1947 and 1952, looking to remake their lives, rebuild their families, and recreate their communities. Integration was not seamless. As survivors struggled to carve spaces for themselves within the established Canadian Jewish community, their difficult wartime stories were neither easily received nor understood. When remembering this period, survivors tend to speak about employment, education, dating, integration into both the pre-war Jewish community and the larger society, and, perhaps most importantly, the creation of their own social worlds within existing and new frameworks. Forged in a transitional and tumultuous period in Quebec’s history, these social worlds, as this article demonstrates, are an important example of survivor agency.

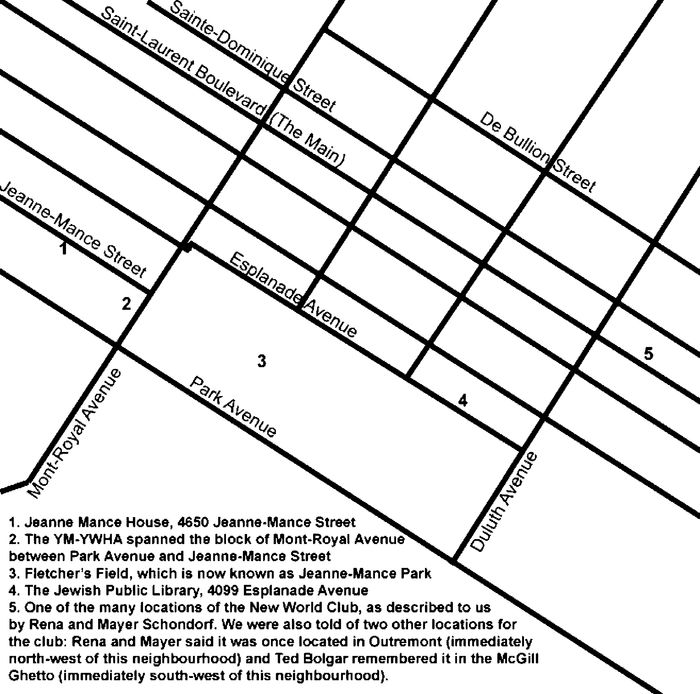

Although survivors recall the ways in which Canadian Jews helped them adjust to their new setting, by organizing a number of programs and clubs within various spaces—Jeanne Mance House, the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association, and the Jewish Public Library—they also speak about how they forged their own paths upon arriving in this postwar city. For instance, survivors created the New World Club, an informal and grassroots social organization where they could prioritize their own needs and begin to be understood as people, and not just survivors. Establishing the interconnections between these formal and informal social worlds, and specifically, how survivors navigated them, is central to understanding the process through which they were able to move beyond their traumatic pasts and start over. Nightmares and parties are parts of the same story, and here the focus is on the memories of young survivors who prioritized their social worlds.

Anna Sheftel and Stacey Zembrzycki have created a short movie about child Holocaust survivors’ postwar social worlds, using clips from the life story interviews that they conducted with them as part of the Montreal Life Stories project. To view this movie, go to: http://citizenshift.org/we-started-over-again-we-were-young.

Résumé

Des milliers d’enfants survivants de l’Holocauste sont arrivés à Montréal, au Québec, entre 1947 et 1952, cherchant à refaire leurs vies, reconstruire leurs familles et recréer leurs communautés. L’intégration n’était pas sans faille. Non seulement les survivants ont-ils du mal à se tailler une place au sein de la communauté juive canadienne existante, leurs pénibles récits de la guerre ne sont ni facilement reçus, ni facilement compris. Se rappelant cette période, les survivants ont tendance à parler de l’emploi, de l’éducation, de rencontres et d’intégration à la fois dans la communauté juive et la société d’avant-guerre et, plus encore, de la création de leurs propres univers sociaux dans de cadres établis ou récents. Créés dans une période transitoire et tumultueuse de l’histoire du Québec, ces mondes sociaux, comme le montre cet article, sont un exemple important de la volonté d’agir des survivants.

Bien que les survivants rappellent comment les Juifs du Canada les ont aidés à s’adapter à leur nouveau contexte, en organisant un certain nombre de programmes et de clubs au sein de différents espaces – Jeanne Mance House, la Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association et la Jewish Public Library – ils racontent aussi comment ils ont forgé leur propre voies en arrivant dans cette ville d’après-guerre. Par exemple, les survivants ont créés le New World Club, un organisme social informel et populaire où ils pouvaient donner priorité à leurs propres besoins et commencer à être compris comme êtres humains et non seulement comme survivants. Démontrer les interconnexions entre ces mondes sociaux formels et informels et, plus particulièrement, comment les survivants y ont navigué, est essentiel à la compréhension du processus par lequel ils ont pu dépasser leurs expériences traumatiques et repartir à zéro. Cauchemars et fêtes sont deux versants d’une même histoire; l’accent ici est mis sur les souvenirs des jeunes survivants qui ont accordé la priorité à leurs mondes sociaux.

Anna Sheftel et Stacey Zembrzycki ont crée un court-métrage ayant pour thème les univers sociaux de l’après-guerre des enfants survivants de l’Holocauste. Elles ont utilisé des extraits tirés de leurs entrevues réalisées pour le projet Histoires de vie Montréal. Pour visionner ce film, visiter le lien suivant: http://citizenshift.org/we-started-over-again-we-were-young.

Article body

Surviving the Holocaust was a kind of a gift which came with two obligations. One was to ensure the continuity of the Jewish people. So I came here, I got married, two children, six grandchildren, this is done! The other part is . . . not to let the world to forget the Holocaust.

—Ted Bolgar[1]

Ted Bolgar, a Hungarian Holocaust survivor who immigrated to Montreal in 1948, repeated this statement several times during a recent interview with us. A prominent figure in Montreal’s Jewish community, Ted frequently gives testimony in schools and participates in public Holocaust commemorations. He has not, however, always been so forthcoming. He began to tell his story only after he remade his family, as his two obligations in life had to occur in order. While Ted’s perspective should not be generalized to all survivors, it is instructive because it helps us understand how he (and others) rebuilt his life.[2]

Our interview with Ted was conducted as part of the Life Stories of Montrealers Displaced by War, Genocide, and other Human Rights Violations project at Concordia University. A community-university collaborative project, it aims to interview 500 people who migrated to Montreal after experiencing large-scale violence.[3] Researchers are devoted to a multiple, life story interviewing approach that privileges spending time with interviewees, building trust, and sharing authority within the interview space and throughout the research process.[4] As part of the project, over eight months, a team of interviewers met with eighteen Holocaust survivors who give testimony in public settings, wanting to understand survivors’ motivations for doing so; what they learned from recounting publicly; how they transformed their memories into narratives that could be adapted to various settings; and what they thought was missing in Holocaust education. This was a significant sample, given that there are only about thirty men and women in Montreal who do this work. All of our interviewees were of Ashkenazi origin and all were affiliated, to varying degrees, with Montreal’s mainstream Jewish community. Our research did not bring us into contact with Hassidic or non-affiliated Holocaust survivors, and therefore the stories that we heard reflect this context. Concerned with understanding the whole trajectory of survivors’ lives,[5] we focused on their educational and commemorative work and also asked them to reflect upon their whole lives. Consequently, we learned just how transformative the postwar period in Montreal, and especially the years between 1947 and 1952, was for our interviewees, who were incidentally quite young (between sixteen and twenty-four years old) when they arrived. Many seemed to fit Ted’s paradigm: upon landing in Montreal they immediately focused on building or rebuilding their families. If we were to understand how these survivors began to fulfil their second obligation, of telling their stories, it was clear that we would also have to learn about their postwar experiences. While many interviewees had already been interviewed by researchers from other projects, few had been asked to speak about these early years of adjustment.[6]

While survivors explained how they rebuilt their lives in postwar Montreal, they shared stories about employment, education, integration into the pre-war Jewish community and the larger society, and, perhaps most importantly, the creation of their own social worlds within both existing and new frameworks. In using the term social worlds we are referring to the physical and temporal spaces in which survivors socialized and networked. As they tried to integrate into Montreal society and make new friends and business partners, they forged social connections that helped them “start over.” Some of these connections were made in mainstream Jewish communal spaces and others were established in informal settings that were carved out by survivors themselves; we view these spaces as “worlds” so as to reflect the richness and diversity present in these stories. Forged in a transitional and tumultuous period in Quebec’s history, these social worlds, as this article demonstrates, are an important example of survivor agency.

Although survivors recalled many clubs, associations, and other networks that the local Jewish community created for them, we were most struck by the social spaces that they built themselves. While this subject crops up in the literature on Holocaust survivors in Canada,[7] it deserves more attention. Of particular interest to us is the New World Club (NWC), a unique organization run by and for survivors, which had no affiliation with the mainstream Jewish community. While the community-organized support systems and clubs are well represented in archival records, we could not find a word about the NWC in print. Despite this absence, we learned that this transient, informal, and grassroots social organization was very important to some of our interviewees during their early years in Montreal. Survivors established spaces, such as the NWC, not only as a means of asserting their independence in a community that was both welcoming and alienating, but also to help them fulfil that first obligation of recreating family, whether or not that family was biological.

Why Oral History?

This article builds on the well-established literature on the reception and integration of Holocaust survivors in Montreal and Canada by examining this period of adjustment from survivors’ perspectives.[8] Our “bottom-up” approach seeks to balance “top-down” studies that draw largely on the established community and gatekeepers’ records. Individuals in the moment are not privy to the same archival documents that historians use for their research; most of the research conducted by survivors was a result of their own observations. Given the lack of documentation about survivors’ social worlds, and the fact that this population is aging quickly, there is a sense of urgency to our research. Speaking with survivors inspired us to write this article; our interviewees’ stories are complex and important.

While much of the scholarship on Holocaust testimony focuses on how survivors struggle to recount their wartime experiences and negotiate the cancellation of memory,[9] comparatively little attention has been paid to survivors’ experiences after the violence, and how they defied their destruction by rebuilding their lives. Scholars of Holocaust testimony believe that memory is affected by postwar experiences,[10] yet survivors’ postwar lives are still not treated with the same depth as the Holocaust itself. Prominent survivors who have written and spoken about the Holocaust never left Europe, and so their stories say nothing about migration. While Elie Wiesel is an obvious exception because he did emigrate, he too has rarely touched this topic. If the travail de mémoire,[11] when speaking of atrocity in the twentieth century, is that of truth speaking to power and survivors reacting to a Nazi project aimed at silencing them, then it is important to examine how that legacy carries on in the postwar world.

Working with Child Survivors

All of our interviewees were child survivors, primarily because few adult survivors remain with us. Most identify explicitly with this title, and we learned that child survivors had particular experiences. Upon arriving in Montreal, our interviewees were undergoing two major changes in their lives: they were children becoming adults, and they were immigrants adjusting to a new country. Some arrived with family, some came to stay with relatives already living in the city, some immigrated alone, and some came with friends through the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) war orphans project.[12]

Child survivors, as Sidney Zoltak explained to us, were not viewed as real victims by adult survivors and were not encouraged to speak about their experiences. As Sid put it, he and his peers were at the very bottom of a survivor hierarchy because “I was too young to remember, or maybe not too young to remember, but maybe I was too young to feel, according to some.”[13] If there were competing survivor narratives in a family, it was often the children’s stories that were lost. In Sid’s case, his mother remarried soon after coming to Canada and his stepfather’s story—a dramatic and sufficiently “gory” concentration camp narrative—dominated the family’s narrative.[14] This hierarchy meant that young people had to negotiate their own space, even within the sub-community of survivors.

Paula Draper has written extensively on how survivors in Canada continued to survive the Holocaust every day.[15] While there seemed to be a wide range of experiences among our interviewees—each survivor dealt with memory and trauma differently—a common element of many stories was this dedication to rebuilding their social worlds. Most survivors married within two to three years of coming to Montreal and had children shortly thereafter, or when they could afford to do so.

Despite the fact that the experiences of child survivors were silenced, Mayer Schondorf explained how youth allowed them to more easily integrate into society: “Age was in [our] favour—the fact that we did not have the baggage of having had wives and children who were lost during the war. We started over again, we were young.” As for dealing with trauma and loss, Mayer said, “We had all these traumatization[s] on the backburner” but chose instead to focus on “what am I gonna do with myself [now].”[16] While adults may have been grappling with what they had lost, youngsters focused on ensuring “the continuity of the Jewish people” and set about rebuilding their lives by making friends, finding jobs, and falling in love. This is not to say that the postwar years were easy for child survivors. Difficulty was coupled with an impetus to move forward, which helps to explain why their social worlds were so important. Our intent is not to ignore or minimize trauma, but to illustrate the complexity of survivors’ early years in Montreal. While trauma has been given considerable attention in the literature, how survivors went on with their lives, while living with it, has not.[17] Nightmares and parties are parts of the same story, and here our focus is on the memories of young survivors[18] who prioritized their social worlds.[19]

Socializing in Context

Child survivors began to rebuild their lives in a city that was tenuously transitioning. First, Quebec’s repressive Duplessis regime came to power in 1944; Duplessis himself campaigned on anti-Semitic rhetoric, which claimed that resettlement efforts were part of an international Jewish conspiracy.[20] While the vociferous anti-Semitism of the francophone majority is well documented, it must be noted that Montreal’s anglophones were also notorious for an anti-Semitism that was “silent, subtle and, in practice, more destructive.”[21] Survivors’ reception was complicated by the fact that Montreal was an ethnically, linguistically, and religiously divided city. Composed of “three solitudes,” divisions among and between French Catholics, English Catholics, English Protestants, and Jews made this host society a complicated place for survivors to navigate. These divisions also made it hard for Jewish Canadians to gain a foothold in society. While a number of Jews had come to Montreal in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Eastern Europeans who fled pogroms in the early twentieth century as part of a massive wave of migration composed much of the city’s pre-war Jewish community. This group was just starting to “make it” when the Second World War broke out; success in business had enabled them to begin moving to more affluent parts of the city, and upward mobility became a priority for them.[22] This community was therefore uneasy about its place in Quebec society and the CJC’s plan to bring survivors to Montreal.[23] How survivors negotiated a place for themselves within Quebec, Montreal, and the pre-war Jewish community was complicated by these factors.[24]

Despite these challenges, Jewish Canadians went to great lengths to help survivors resettle in Montreal and were responsible for establishing the Jewish social services and institutions discussed below. It must be noted that once survivors settled, they became a proportionately large part of the Jewish population, compared to other sites of resettlement in North America.[25] The ways that survivors established themselves and their families in postwar Montreal thereby had a lasting effect on the local Jewish community and on the city itself.

As numerous authors have noted, both the Jewish and non-Jewish public was unprepared to receive survivors’ stories in the immediate postwar years; they were either too difficult to hear, caused too much guilt for the listener, or were too unbelievable.[26] This exacerbated tensions. Krysia,[27] who worked as a live-in domestic when she arrived in Montreal, recounted a harsh statement made by her Russian Jewish boss: “You are such a pretty young woman, I wonder how you survived? You probably flirted with the Germans, and I understand, it was the war.” Krysia continued, “So she shut me up for about forty years, I think. I couldn’t talk. So that was the attitude: if you survived then you’re a scum, and if you didn’t you’re a victim, and that’s it. And that was the attitude of Canadians: they just didn’t have imagination, they didn’t understand. I survived because I was lucky, people helped me. And my own courage.”[28] We asked Krysia how she dealt with this insensitivity and she told us, “They didn’t understand. And that’s why we didn’t talk . . . for years . . . But if you would ask me sixty years ago ‘How did they treat you?’ I would say ‘Nobody hit me.’ But now I’m angry. I’m angry now.”[29] Whatever the reasons for this breakdown in communication between pre-war Jews and newcomers, a silencing occurred. This experience of being misunderstood affected survivors’ new social worlds. It helps to explain why they often chose to associate only with other survivors. It was more comfortable to be with those who had lived the Holocaust, whether or not one chose to speak about it, for, as Mayer explained, “You didn’t have to talk about it because everyone knew what had happened.”[30]

Feeling like they were social pariahs led survivors to build their own social worlds. Many told us that Canadians were discouraged from dating survivors because of their lower social status. Usually poor upon arrival and with their education interrupted, survivors were considered “too broken” to be suitable candidates for marriage. They were called “greener,” “greenhorn,” “gayle,” and “mucky,” among other epithets. When speaking about these kinds of characterizations, Ben Younger recalled an incident when a customer repeatedly called him “mucky” while he was working behind the counter at a diner shortly after coming to Canada. In response, Ben jumped over the counter and beat up the customer. For Ben, the term “mucky” spoke to larger Jewish-Canadian fears: that newcomers like him would take away jobs and thereby disrupt the community’s ability to attain upward mobility.[31]

Moreover, psychological testing fed into perceptions that survivors ought to be ostracized. Indeed, we were surprised to discover that many of our interviewees remembered being deemed severely traumatized and thus unable to recover from their experience. It should be noted that our own research into a sample of case files from the CJC’s war orphans project did not suggest that most or all child survivor patients were diagnosed so harshly,[32] and the literature states that the vast majority of survivors remade their lives.[33] Still, memories of harsh diagnoses led survivors to feel stigmatized, regardless of what gatekeepers concluded.

In the introduction to their co-authored book, Henry Greenspan recounts how he met Agi Rubin, a survivor, while listening to a panel about survivors’ postwar experiences. A social worker on the panel who had worked with the refugees stated, “To be honest, we really didn’t know how to handle them. We didn’t know how to handle the survivors at that time.” “I can still hear Agi’s response,” writes Greenspan. “We didn’t realize that we had to be ‘handled.’”[34]Concentration-camp survivor syndrome, a term coined by W. G. Niederland in 1961, had a strikingly long list of symptoms: sleep disturbances, chronic depression, repressed mourning, and psychic closing-off.[35] With such paradigms for assessing them, one wonders how any newcomer could have “recovered.” Survivors were aware that they were being psychologically and socially scrutinized, and many clearly resented it. Ted Bolgar now laughs when he recalls all of the psychological tests that he endured: “The general idea was that we’d never make it.” When asked to explain what he meant by “make it,” Ted said that David Weiss, executive director of Jewish Family and Children Services in Montreal, felt that “we were so damaged by the experience that we wouldn’t be able to meld into the society and make a normal life.” For Ted, “normal” meant finding and keeping a job, getting married, and having children.[36] According to Fraidie Martz, who worked with survivors in the Department of Psychiatry at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital, Weiss adopted a very cautious approach toward survivors, warning the Jewish community that many of the children would suffer nervous breakdowns.[37] Ted declared, “We proved him wrong.[38]

It would be provocative to claim that newly arrived child survivors acted out of a sense of rebellion, yet they were in part countering these troubling predictions and tense circumstances when they created their social worlds. They carved out numerous spaces for themselves to enable social networking, to disprove the community’s depressing diagnoses, and to create spaces where they could feel like people, rather than survivors. All three purposes were interrelated and influenced each other.

Mainstream Jewish Communal Spaces

In 1949, Mary Palevsky, who worked for the Council for Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds in New York, wrote a report for the CJC, documenting the efforts to resettle and integrate survivors and suggesting how local Jewish organizations could improve their practices. While many of our interviewees remember these services positively, Palevsky is far more critical: “On the whole . . . the services for the immigrants were not well administered because there was a lack of (1) clarity as to the aims and objectives of the refugee program; (2) of advanced planning; (3) of sufficient numbers of professionally qualified workers; (4) of professional direction and coordination.”[39] Palevsky sets out a series of recommendations that call for more trained social workers, more educational efforts, and more social spaces, especially for young people. Reaction to the document was mixed and controversial, particularly to her suggestions for the roles of the organizations involved.[40] In light of such controversy, this section will discuss how the mainstream Jewish community tried to help young survivors rebuild their social worlds, and how survivors remember those efforts.

The Jewish community established a number of programs and clubs within existing and new spaces—Jeanne Mance House, the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YM-YWHA), and the Jewish Public Library (JPL)—that were designed to meet the needs of the new refugees.[41] These spaces were all in close proximity to one another, around Saint-Laurent Boulevard, or the Main—a neighbourhood that was undergoing significant transition in the years following the Second World War. As upwardly mobile Jewish-Canadian families left this area and moved to new suburbs in the north and west ends of the city—such as, Snowdon, Hampstead, and Côte Saint-Luc—Jewish refugees and their families made this neighbourhood their home. The city’s immigrant corridor, the Main also served as a home for other postwar immigrants, including members of the Greek, Portuguese, and Hungarian communities. Although it would not be long before survivors followed Canadian Jews and moved to the suburbs, the Main remained the heart of Montreal’s Jewish community in the immediate postwar period. It housed synagogues, smoked-meat shops, and kosher butchers, and Yiddish could be heard on the streets. There were numerous garment factories and sweatshops in the area, owned by Jews and employing Jewish workers. The workers, who were among the poorest Jews, lived on the streets located on the east side of the Main, while slightly more affluent Jews, such as small merchants, lived on the west side. Factory owners lived west of this neighbourhood with French-Canadian elites in Outremont, while “rich” Jews descended from “new and old money” lived in prestigious and largely anglophone Westmount.[42] Survivors settled wherever they could find accommodations.

One community-created space was Jeanne Mance House, a reception centre for orphaned survivors under the age of eighteen, who came to Montreal from 1947 to 1949. Located at 4650 Jeanne-Mance Street, on the second floor of the Herzl Dispensary,[43] the centre could accommodate thirty to fifty youths.[44] Since, as Ben Lappin notes, “the supply [for free homes] could never keep up with the demand,” the house served as an “interim [dwelling] while the survivors awaited permanent placements.”[45] Upon arriving, the children were welcomed, given a tour, and informed of the rules and routines. Ben Younger fondly recalls setting foot in Jeanne Mance House, remembering that the orphans were gathered together and told, “Listen, now you are in a wonderful, wonderful country. Don’t worry, you don’t have to be afraid here in this country.”[46] While our interviews indicate that these early days were happy ones for most orphans, they could also be overwhelming. Unable to believe that she did not need an identification card to leave the reception centre, Musia Schwartz remembers having to adjust to her new-found freedom.[47] Frightened by the sight of police officers, Ted Bolgar made a habit of approaching them and asking for directions so that he could overcome his phobia. These were adjustments that would take time.[48]

Jeanne Mance House was a busy “neighbourhood settlement” that left the orphans with little privacy.[49] Palevsky states that the “reception centre soon became the target of such great community enthusiasm that it was impossible to keep it under control.”[50] Mayer Schondorf remembers it being wild and lively, while Musia goes further, declaring that it was “like a [DP] camp,” because there were twenty cots in one large room and the children were all playing pranks on one another.[51] Canadian Jews looking to welcome a child survivor into their homes would visit the centre twice a week for an open house. During these “open nights,” children were put on display and, as Musia admits, they often felt like “window pieces.”[52] While the prospect of being placed in a Canadian home was exciting, the possibility of rejection was also very real and frightening.[53] To add to this traffic, war orphans who had already been placed in homes frequently returned to the centre; even child survivors who did not come to Canada as war orphans visited Jeanne Mance House to “meet with the other children.”[54] It was not only a resource centre but also a space where survivors could interact with other survivors; they maintained old friendships and forged new ones, and also heard news about Europe from recent arrivals. Given the gulf between Canadians, local Jews, and survivors, Jeanne Mance House was a comfortable place where these children could be among peers whom many considered to be “like family.”[55]

Postwar survivor spaces

In addition to meeting Canadian Jews and interacting with other child survivors, those living in the reception centre encountered volunteer and professional gatekeepers, including social workers, doctors, dentists, psychologists, and vocational guidance councillors.[56] Social workers conducted interviews with the children, and vocational guidance councillors tested adolescents, determining whether they ought to enrol in school or enter the labour force immediately.[57] While some were given the opportunity to continue their education, many turned down the offer, choosing instead to enter the workforce. Mayer, whose test results revealed that he should work with figures, took advantage of the English classes that were offered at the centre, but decided to find a job rather than go to school for five years to become an accountant. After meeting Rena, his wife for fifty-seven years, he wanted freedom and independence and this, he believed, could be obtained only by working and earning his own money.[58] Musia was also encouraged to resume her studies but, like Mayer, she wanted to be independent, remembering, “I didn’t want it. I wanted to earn my own money and not live on handouts. I knew I’d go to university, in my own sweet time.”[59] A desire for independence was key in the early decisions that many survivors made, determining how they organized themselves socially.

Educational activities were also held at Jeanne Mance House; although optional, the children were strongly encouraged to attend them. Accelerated language courses, designed to give the children a working knowledge of English, took place in the mornings while afternoons were spent introducing them to life in Canada.[60] Volunteer groups organized activities that included picnics, concerts, plays, shopping trips, local excursions, and for those who had been personally invited, visits to the private homes of Canadian Jews.[61] Ben remembers one of his first excursions fondly. When he awoke on his second day in the reception centre, he and the other war orphans were taken to a local factory to pick a suit: “We went up to Cooper Clothing. I remember the name of the factory, on Saint-Laurent near Duluth, and everybody picked his own suit.”[62] A desire to look like a Canadian and speak English were, according to Greta Fischer and Pearl Switzer, very important attributes for these refugees, enabling them to begin to “feel normal.”[63] Jeanne Mance House may have served as an effective starting point for survivors to begin to remake their lives, providing them with resources and a sense of comfort, but it was just that, a starting point. For these refugees, rebuilding would take place outside the watchful gaze of gatekeepers.

In addition to Jeanne Mance House, the YM-YWHA served as a communal space for survivors in Montreal. Located at the corner of Mont-Royal Avenue and Jeanne-Mance Street, steps away from the reception centre, the YM-YWHA encouraged child and adult survivors to participate in its programs and offered free memberships to war orphans. Gatekeepers hoped that YM-YWHA programs would help refugee youths integrate into the larger Jewish community, socializing in a more diverse yet still controlled space. While gatekeepers indicated that “mixed meetings” between child survivors and Jewish Canadian youths were successful, survivors’ memories tell another story.[64] Few remember interacting with these children. Instead of forming integrated groups, survivors subdivided among themselves and formed newcomer groups. While language barriers were an obvious hurdle, survivors report that Canadian Jewish youths also scrutinized them and treated them differently. Tired of being “on display,” child survivors resisted many attempts to intermingle with Canadians.[65]

Nevertheless, 175 war orphans eventually formed eleven separate newcomer clubs within the YM-YWHA.[66] While these subgroups flourished, there was also a separate club for all newcomers: the New Canadian Club. Meeting weekly and publishing a bimonthly bulletin, New Life, in English and phonetic Yiddish, the group was formed soon after the orphans began to arrive in 1947 and disbanded in June 1948. The transient nature of this club is typical of the ones that survivors remember: they existed only as long as they had a purpose. Bulletins indicate that the New Canadian Club served as a social networking space, enabling survivors to interact with other survivors; some of these relationships eventually led to lifelong friendships and marriages. When asked about where he met other survivors during this period, Sidney Zoltak referred to the YM-YWHA: “They had different clubs, socials, get-togethers. It was one way to meet.”[67] While Musia Schwartz did not remember participating in particular programs or clubs, she had no difficulty recounting the fun that she had attending newcomer dances. Here she met Lucy, a survivor who became a sister and lifelong best friend. For Musia, the YM-YWHA was a place where she and her friends, who tended to be other survivors, would gather before heading to other locations. From there they would go for walks, to nightclubs, and to Mont Royal, where they would sit on blankets and listen to free concerts.[68]

Nevertheless, a YM-YWHA memorandum reveals that the New Canadian Club struggled to garner interest. As of November 1948, “a. Only five members of the New Canadian Club executive were active. b. The Wednesday and Sunday night cultural meetings drew a tiny attendance or no attendance at all. c. The only activity well attended was the Saturday social dancing. d. There was complete lack of organized sports.”[69] Although organizers planned social events designed to appeal to the young survivors, they struggled to draw them in. When we asked Mayer Schondorf why he did not socialize at the YM-YWHA, he told us, “The YMHA was for everybody. And you felt you wanted to have your own . . . The Y had an entirely different function . . . You went there for a swim, you went there to exercise. You did not stay in the Y . . . basically [the] Y had its own raison d’être.”[70] Perhaps the YM-YWHA had trouble presenting itself as a safe space for survivors to be together. Many survivors were most comfortable building relationships with those who shared experiences with them. As Sid stated, “We knew who was and wasn’t survivors right away . . . No one had to do us a favour, we were on equal grounds.”[71] Survivors also took control of the events that occurred in the YM-YWHA, not only deciding who they would befriend, but also determining the kinds of clubs that they would belong to and the programs that they would participate in. Furthermore, it was an especially short-lived experience. Our interviewees, those who could either afford memberships or had free ones, admitted to frequenting the YM-YWHA only during their early years in Montreal. When they had made friendships and learned enough English to get by, they created their own informal social worlds outside of this organization. Like Jeanne Mance House, the YM-YWHA was a space that gave survivors tools they would need to adapt to life in Canada, but it was not enough for them.

Lastly, the JPL was an important communal space for child and adult survivors. This was not an exclusive place that required any type of membership or association. Given its accessibility, it looms large in many of our interviewees’ memories. Located at 4099 Esplanade Avenue, a couple of blocks away from both the YM-YWHA and Jeanne Mance House, the library contained a folksuniversitae (YIFO) that organized courses on Yiddish literature, Bible studies, Jewish history, and world history. Popular among postwar refugees interested in learning about Canada and gaining a working knowledge of English and/or French, each course comprised ten to thirty lectures (depending on the instructor), lasted one hour, and cost participants twenty-five cents a lecture.[72] When remembering the JPL, survivors focused mostly on the English-language classes that they attended—a fact that is not surprising, given that few of them speak French.[73]

When Krysia arrived at the train station in Montreal on 13 December 1948, she had only five dollars stuffed into her bra. Unlike the large crowds that arrived to greet the CJC’s war orphans, no one welcomed her when she stepped off the train. Krysia’s first impressions of Montreal are difficult to hear: “It was cold, cold, cold and I didn’t know anybody. It was very hard . . . a disappointment.” After securing a job as a live-in domestic, Krysia registered for English classes at the JPL, the only place that she made contact with other survivors. She stated,

Once a week, we [the refugees] would meet in the library. I got myself a reputation there, I’m intellectual, because I had only one pair of shoes, those little pumps, and already there were holes in them. It was winter, so I would stuff them with newspapers. So I was embarrassed, everybody was wearing boots. I would come to the library first, you know, sit there, and left the last one . . . So they knew to always see me in the library because of my shoes. So I was pretending, you know I’m sitting there and reading or whatever, and I was embarrassed they should see that I’m wearing that one pair of dirty . . . torn shoes. So I came first and I left last, always.

Although it took Krysia a great deal of courage (and planning) to arrive at class each week, she stressed that her first priority was to learn English and that the JPL was the only place she could do so. If she could learn English, she could get a better job. The JPL also gave Krysia an opportunity to meet other survivors who were enduring similar experiences. While their conversations were superficial—centred mostly on sharing survival strategies—they were helpful because they offered her valuable advice. Unlike other interviewees, Krysia’s story does not focus on how she actively rebuilt her social world; she described a great deal of loneliness and difficulty during her early years in Montreal. What is significant is that the only moments that seemed to ease her isolation were those spent at the JPL. Krysia was able to find a better job as a result of the social network that she developed there, easing some of the problems that she faced when integrating into the local community.[74]

The JPL was also an important space for Olga Sher and Musia Schwartz. Arriving in Montreal from Poland, they too prioritized learning English. For Olga, integration came only with learning the language.[75] Musia shared similar thoughts and declared that the JPL “was the only institution that I really have very fond feelings for . . . They were a beacon.” Musia frequented the JPL so that she could borrow English and Polish books from its diverse collection; English ones were for learning and Polish ones were for pleasure. Eventually, after a discussion with a JPL librarian, she enrolled in the poet Irving Layton’s English class. Here she not only met her husband, but also began a fifty-year friendship with Layton. Musia is still in awe when she speaks about this class, stating that no one but Layton could have “[pulled] it off.” The class, which was composed of recent immigrants who had a minimal knowledge of the English language, would sit around a table and listen to poetry. Layton would read the poems and then ask participants to respond to them. Although Musia was hesitant to express herself because of her limited language skills, others would share their feelings and their wartime stories. This was an important forum for Musia, because Layton was sensitive and responsive to what he heard: “He was the only person I met who wouldn’t trivialize or leave any story unfinished until he thoroughly understood it.”[76] Of course, not everyone felt the same way. For others, the JPL was like every other mainstream Jewish organization, simply helping them develop skills that made integration easier. Notably, this was however one mainstream Jewish organization devoid of gatekeepers, where survivors could resume their interrupted educations, one of the more difficult aspects of their wartime experiences, with little to no scrutiny.

The New World Club

While Jeanne Mance House, the YM-YWHA, and the JPL tried to help survivors adapt to life in Canada, they did not fulfil all of survivors’ needs. Members of the Jewish community, as Mayer Schondorf declared, “were extremely helpful in every respect you can imagine, except socially. Socially we were the greenhorns.”[77] Our interviewees stressed the importance of unregulated and informal spaces in their narratives, privileging them over those within the larger community. According to Mayer, socially Canadians “wanted to have very, very little to do with us. So we created our own social.”[78]

Ben Lappin states that a number of independent European youth clubs, organized by and for survivors, sprang up in Montreal in the postwar period. Members rented spaces above stores in the city’s downtown core and proceeded to decorate and convert them into clubrooms. Survivors stressed that these clubs gave them an opportunity to have separate social lives of their own, giving them a space where they could sing European songs, discuss “matters of common interest,” and just gather whenever and for however long they wanted.[79] Other than this brief description, the archives reveal little about these informal clubs. Nevertheless, stories about such clubs, and particularly the New World Club (NWC), live on in the memories of a number of our interviewees. The NWC served as both a social networking space and an immigrant aid organization.

According to Rena Schondorf, the NWC was founded by two men, Dr. Reichman and Dr. Pfeifer, German Jews who arrived in Canada during the war and were interned as German prisoners of war; the Canadian government did not differentiate between the ethnicities of interned Germans.[80] After the Jewish community convinced the government to release them, Reichman and Pfeifer settled in Montreal and established the club. Early members were some of the first European Jews who arrived from England. It did not take long for the club to mushroom, becoming an important space for new arrivals.[81]

Ted Bolgar joined the NWC soon after arriving in Montreal as a war orphan in 1948; at twenty-four years of age, Ted was desperate to leave Hungary and admits, without guilt, that he lied about his age in order to qualify for the war orphan’s project. Ted was interested in starting a new life. He wanted to make friends and meet girls and he thought that the NWC would be an ideal venue. Ted heard about the club by word-of-mouth. There was no need for publicity; it was a social club that everyone just knew existed. According to Ted, the members, who were all survivors, met every Sunday afternoon in a rented space in the McGill ghetto, the neighbourhood adjacent to McGill University, on the second floor above a store. There was a president, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer, and every member paid a small membership fee to cover the rent.[82] Interestingly, no one could tell us if the NWC was affiliated with mainstream Jewish organizations or received external funding.

Two rooms contained two separate groups, composed of adult and child survivors, within the space rented by NWC members. While the breakdown of the group is unclear, Ted explained that the club numbered about two hundred survivors and that more adult than child survivors belonged. When asked whether he or other child survivors interacted with adults, Ted quickly stated, “We weren’t interested in the older generation . . . They were separate”; Mayer and Rena Schondorf echoed this statement, declaring that they were “ancient” and did not want to have anything to do with them.[83] Child and adult survivors organized and participated in different events. Adults listened to speeches, arranged guest lectures, and recited poetry, while the younger generation attended NWC meetings for the dances. Despite their differences, both adult and child survivors valued the NWC because it was a space where they could tell stories and “be together.” When asked whether these stories focused on the Holocaust, Ted stressed, “No! We all knew what had happened. We didn’t have to tell anyone about it. We just wanted to have fun.”[84]

The NWC’s child members were a diverse group. They were between the ages of nineteen and twenty-six and came from a variety of countries as war orphans, on their own, or with family members. Since few could converse in English, the group was loosely divided along linguistic lines, forming “cliques within the club.” Hungarians tended to befriend and date other Hungarians, while those who spoke a Slavic language were a little more flexible in their social mobility. Despite this challenge, all members came together for occasional outings and weekly dances. The NWC holds a special place in Ted’s memories because that is where he met his wife. He also stressed that it was a refuge because “the reception issues we faced were difficult. Montrealers didn’t know who we were. They were leery of us.”[85] Ted’s involvement in the NWC revolved around the social opportunities it afforded him.[86] Whether or not the Holocaust was explicitly discussed in this space, it is what bound the club’s members to each other; they came together to socialize around people who just understood.

For others, the NWC was not just for socializing. Mayer stated, “It’s called ‘club’ but it wasn’t a fun club. It was more an aid, a help club. [We helped] each other and of course at the same time you created friends.” Rena and Mayer, who met at an NWC event and married shortly thereafter, participated in the club so that they could get advice from other survivors and hear about employment opportunities. According to Mayer, there was a significant difference between having a personal connection with someone already working within a company, and showing up at the company’s office with a note from the Jewish Immigrant Aid Service office. It meant the difference between getting and not getting a job. NWC members also gave the Schondorfs information on “the basics,” telling them about education and housing options and day-to-day necessities, like where to shop for goods on consignment. “There were all kinds of people trying to establish themselves,” and this kind of information was crucial for them.[87]

Most importantly, the NWC cost survivors little to nothing. As Rena declared, “You see, this was part of entertainment. You had no money [so] you went there for an evening.” In addition to lacking disposable incomes, survivors had very little space where they could congregate. Apartments were cramped and often shared, so people did not gather at each other’s houses. It was not until Rena and Mayer married and purchased their first home that they hosted friends in their own space. Every Sunday, they and their friends, many of whom they had met at the NWC, would sit on Coca-Cola crates around a folding bridge table and Rena would serve whatever she had on hand.[88]

As survivors began to integrate into the larger society, the NWC no longer served an immediate purpose for them, and so it disbanded around 1951. They had found jobs, gotten married, started families, and either bought or rented their own homes. Busy with their new lives, survivors lacked time and interest in the club.[89] At this point, the survivor community was also bigger and better at handling the arrival of new immigrants, so newcomers had less need for the social worlds of those who had come in 1948 and 1949; additionally programs that permitted sponsorship of family members tempered the problems of integration.

After meeting their partners at the NWC, Ted, Rena, and Mayer did not continue to participate in its activities. Convinced of the importance of this informal space for survivors, we expected to hear dramatic explanations of why their involvement ended. Instead, Ted simply declared, “I wasn’t interested. I caught my catch and that was it!”[90] Despite this curt response, the narratives of NWC members speak to a more nuanced history. The club may have been short-lived, but its legacy continues to affect those who once belonged to it. It was a space where survivors forged relationships that would last a lifetime and found employment that would sustain them and their families throughout their years in Montreal. Like Jeanne Mance House, the YM-YWHA, and the JPL, the NWC provided survivors with the resources that they so desperately needed to remake their lives. Unlike these other mainstream Jewish communal spaces, however, the NWC was built by and for survivors. Here they understood and prioritized their own needs, rebuilding their social worlds on their own terms.

Conclusion

Both formal and informal social worlds loom large in survivors’ stories about their early years in Montreal. Musia Schwartz met her spouse at the JPL, while Rena and Mayer Schondorf and Ted Bolgar met theirs at the NWC. These spaces had a profound impact on how young survivors remade their lives. They tended to marry other survivors not only because they understood each other, but also because they felt uncomfortable dating Jewish and non-Jewish Canadians; the anti-Semitism of French Canadians and anglophone Montrealers only exacerbated this sentiment.

Two main motivations determined how survivors organized themselves. First, they wanted to assert their independence and reclaim their agency in a city that had offered them a problematic welcome. The result was a proliferation of informal spaces despite the many formal ones described above, as well as the ways that our interviewees made formal spaces their own. Many survivors strongly articulated their desire to be independent, out of pride and in reaction to their sometimes hostile and patronizing treatment. Second, we return to Ted Bolgar’s first obligation as a survivor, “to ensure the continuity of the Jewish people.” Quite practically, this meant pursuing financial, marital, and filial goals. The easiest method was to form communities with other survivors, within the larger Jewish community, or on their own. Finally, survivors’ diverse social worlds combined their old and new lives. The Holocaust was not the only issue dividing Canadian Jews, Gentiles, and survivors; there was also language, culture, and upbringing. For many, beginning anew was easier when they did not have to forget the past or where they had come from. These factors and the instinctual ways that survivors understood each other enabled them to move forward. Just as Ted’s obligations situate his private and public life in a larger context, the social worlds created and experienced by survivors also speak to the ways that the past, present, and future remain intertwined.

Anna Sheftel and Stacey Zembrzycki created a short movie about child Holocaust survivors’ postwar social worlds, using clips from the life story interviews that they conducted with them as part of the Montreal Life Stories project. To view this movie, go to: http://citizenshift.org/we-started-over-again-we-were-young.

Appendices

Remerciements

We would like to thank Steven High, Henry Greenspan, Franca Iacovetta, Jordan Stanger-Ross, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments; Sandra Gasana also deserves praise for processing our interviews. Most importantly, we wholeheartedly thank our interviewees for sharing their memories with us. In particular, we dedicate this article to Mayer Schondorf, who passed away while it was under review. The stories that he and his wife Rena shared with us inspired this research and drove home the importance of telling this story. Research for this article was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Notes biographiques

Anna Sheftel is a postdoctoral fellow in the History Department at Concordia University, and its Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling. She is funded by the Fonds québécois de recherche sur la société et la culture. Her postdoctoral research examines the life narratives of Holocaust survivors living in Montreal, and particularly how they relate to their experiences of postwar immigration and integration into the larger Jewish community.

Anna Sheftel est une chercheuse postdoctorale dans le Département d’histoire de l’Université Concordia et au Centre d’histoire orale et de récits numérisés. Ses recherche sont appuyées par le Fonds de recherche sur la société et la culture. Elle étudie les récits des survivants de l’Holocauste vivant à Montréal, et particulièrement comment ils se souviennent de leurs expériences d’immigration et d’intégration dans la communauté juive.

Stacey Zembrzycki is a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada postdoctoral fellow in the History Department at Concordia University, where she is also affiliated with the Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling. Her research uses life story oral history interviews to understand the postwar narratives and educational activism of child Holocaust survivors in Montreal.

Stacey Zembrzycki est récipiendaire d’une bourse postdoctorale du Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines (CRSH) au Département d’histoire de l’Université Concordia où elle est également associée au Centre d’histoire orale et de récits numérisés. Ses recherches en cours utilisent des interviews biographiques en histoire orale afin de comprendre les récits d’après-guerre et le militantisme scolaire des enfants survivants de l’Holocauste à Montréal.

Notes

-

[1]

Ted Bolgar, interview by Anna Sheftel and Stacey Zembrzycki, Montreal, 6 April 2009. Unless otherwise noted, the authors conducted all interviews.

-

[2]

For a more sustained discussion about why survivors’ voices were silenced for decades following the war, see, for instance, Henry Greenspan, The Awakening of Memory: Survivor Testimony in the First Years after the Holocaust, and Today (Washington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2001); Zoe Vania Waxman, Writing the Holocaust: Identity, Testimony, Representation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

-

[3]

For more information about the Montreal Life Stories project see http://www.lifestoriesmontreal.ca/.

-

[4]

Much of the inspiration for our methodology can be found in Michael Frisch, A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990); Henry Greenspan’s On Listening to Holocaust Survivors: Recounting and Life History (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998); Greenspan and Sidney Bolkosky, “When Is an Interview an Interview? Notes from Listening to Holocaust Survivors,” Poetics Today 27 (2006): 431–449.

-

[5]

Steven High states that “[the] shift from testimony to life history is . . . a fundamental one as the focus becomes the person rather than the event and the perspective . . . to an inward reflection on the meanings derived from one’s own life’s journey.” See High, “From Testimony to Life Story: Re-thinking the Place of Survivor Narratives in North American Immigration History,” unpublished paper, 2009.

-

[6]

Numerous Holocaust testimony projects have interviewed Montreal survivors, including the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) Holocaust Documentation Project, the McGill University Living Testimonies Project, the Montreal Holocaust Memorial Centre Testimony Project, and the Shoah Visual History Foundation. While each project had its own oral history methodology, our interviews were unique because of their multiple, life story approach. See Janice Rosen, “Holocaust Testimonies and Related Resources in Canadian Archival Repositories,” Canadian Jewish Studies 4 and 5 (1996–1997): 163–175.

-

[7]

Franklin Bialystok, Delayed Impact: The Holocaust and the Canadian Jewish Community (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000); Greta Fischer and Pearl Switzer, “The Refugee Youth Program in Montreal, 1947–1952 (MSW thesis, McGill University, 1955); Myra Giberovitch, “The Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations to Jewish Communal Life” (MSW thesis, McGill University, 1988); Ben Lappin, The Redeemed Children: The Story of the Rescue of War Orphans by the Jewish Community of Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1963); Fraidie Martz, Open Your Hearts: The Story of the Jewish War Orphans in Canada (Montreal: Véhicule, 1996).

-

[8]

For a discussion about the reception of survivors, see Bialystok, Delayed Impact; Paula Draper, “Canadian Holocaust Survivors: From Liberation to Rebirth,” Canadian Jewish Studies 4 and 5 (1996–1997): 39–62; Draper, “Surviving Their Survival: Women, Memory, and the Holocaust,” in Sisters or Strangers? Immigrant, Ethnic, and Racialized Women in Canadian History, ed. Marlene Epp, Franca Iacovetta, and Frances Swyripa, 399–414 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004); Giberovitch, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations”; Gerald Tulchinsky, Canada’s Jews: A People’s Journey (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 401–426.

-

[9]

Giorgio Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive (New York: Zone Books, 1999); Richard S. Esbenshade, “Remembering to Forget: Memory, History, National Identity in Postwar East-Central Europe,” Representations 49 (Winter 1995): 72–96; Saul Friedlander, Memory, History, and the Extermination of the Jews of Europe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz: The Nazi Assault on Humanity (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996); Luisa Passerini, “Memories between Silence and Oblivion,” in Memory and Totalitarianism, ed. Luisa Passerini (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 196; Waxman, Writing the Holocaust. For a Canadian discussion about the silences that result when interviewees recall deeply traumatic events, see Draper, “Surviving Their Survival,” 399–414; Marlene Epp, “The Memory of Violence: Soviet and East European Mennonite Refugees and Rape in the Second World War,” Journal of Women’s History 9 (Spring 1997): 61–70; Epp, Women without Men: Mennonite Refugees of the Second World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 48–63; Pamela Sugiman, “Passing Time, Moving Memories: Interpreting Wartime Narratives of Japanese Canadian Women,” Histoire sociale / Social History 37 (May 2004): 70–73; Sugiman, “‘These Feelings That Fill My Heart’: Japanese Canadian Women’s Memories of Internment,” Oral History 34 (Autumn 2006): 78–80.

-

[10]

Charlotte Delbo, Auschwitz and After (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995); Lawrence Langer, Holocaust Testimonies: The Ruins of Memory (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991).

-

[11]

For more on the idea of travail de mémoire, and namely how memory as activist work can challenge history or politics, see Marie-Claire Lavabre with Sarah Gensburger, “Entre devoir de mémoire et abus de la mémoire: la sociologie de la mémoire comme tierce position,” in Sur Paul Ricoeur, histoire, Mémoire, épistémologie, ed. B. Müller, 76–95 (Lausanne: Payot, 2005).

-

[12]

Between 1946 and 1960, 46,000 Jewish immigrants came to Canada. For a discussion about various immigration schemes, see Bialystok, Delayed Impact, 42–67; Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000), 311–345; Tulchinsky, Canada’s Jews, 401–426.

-

[13]

Sidney Zoltak, interview, Montreal, 18 March 2009.

-

[14]

Ibid.

-

[15]

Draper, “Surviving Their Survival,” 399–414.

-

[16]

Mayer and Rena Schondorf, interview, Montreal, 11 June 2009.

-

[17]

Many have studied the role of trauma in survivors’ lives, including John J. Sigal and Morton Weinfeld, Trauma and Rebirth: Intergenerational Effects of the Holocaust (New York: Praeger, 1989). Our concern is that these studies focus on the psychological without balancing it with the social. Notably, Giberovitch’s study, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations,” seems to achieve such a balance.

-

[18]

While adult survivors also constructed their own networks, they seem to have been for different purposes, and not necessarily as forward-looking.

-

[19]

Most of our interviewees fulfilled Ted’s two obligations; they are, by the measures that survivors use, “success stories.” Of course, these survivors are the most likely to share their stories. We cannot make any claims for survivors who have not spoken or who will not speak with us.

-

[20]

Giberovitch, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations,” 46. On the relationship between the Jewish and francophone communities, see Pierre Anctil, Le Devoir, les Juifs et l’immigration: de Bourassa à Laurendeau (Quebec: Institut quebecois de recherche sur la culture, 1988); Anctil, Tur Malka: flaneries sur les cimes de l’histoire juive montréalaise (Sillery: Septentrion, 1997).

-

[21]

John Dickinson and Brian Young, A Short History of Quebec, 3rd ed. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003); Tulchinsky, Canada’s Jews; William Weintraub, City Unique: Montreal Days and Nights in the 1940s and ’50s (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1996), 201.

-

[22]

Joe King, From the Ghetto to the Main: The Story of the Jews of Montreal (Montreal: Montreal Jewish Publications Society, 2000).

-

[23]

Ibid.

-

[24]

Although anti-Semitic sentiments receded and there was a rapprochement between French and English Canadians and Jews in postwar Quebec, tensions did not disappear completely. See Dickinson and Young, A Short History of Quebec, 271–304; Tulchinsky, Canada’s Jews, 408–413;.

-

[25]

Sigal and Weinfeld, Trauma and Rebirth, 6.

-

[26]

For more discussion about this inability to communicate between survivors and non-survivors, see Bialystok, Delayed Impact, 66–68; Draper, “Canadian Holocaust Survivors,” 57; Draper, “Surviving Their Survival,” 408–409; Giberovitch, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations”; Tulchinsky, Canada’s Jews, 403–404.

-

[27]

Krysia requested confidentiality during our interview and therefore this name is a pseudonym.

-

[28]

Krysia, interview, Montreal.

-

[29]

Ibid.

-

[30]

Mayer and Rena Schondorf, interview.

-

[31]

Ben Younger, interview by Matthew MacDonald and Jessica Silva, Montreal, 3 February 2009.

-

[32]

Box 36, general case files (KLE-LEW), case files, War Orphans Immigration Project, United Jewish Relief Agency (UJRA) Collection, Canadian Jewish Congress Charities Committee (CJCCC) National Archive. Gatekeepers declared that the majority of war orphans were “normal” and “well adjusted.” While it is unclear how these gatekeepers defined these terms, a number of scholars in the field have done a good job of doing so. See, for instance, Mary Louise Adams, The Trouble with Normal: Postwar Youth and the Making of Heterosexuality (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); Elise Chenier, Strangers in Our Midst: Sexual Deviancy in Postwar Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008); Mona Gleason, Normalizing the Ideal: Psychology, Schooling, and the Family in Postwar Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999); Franca Iacovetta, Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006). For an in-depth discussion about using case files in historical research, see Franca Iacovetta and Wendy Mitchinson, eds., On the Case: Explorations in Social History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998).

-

[33]

See Fischer and Switzer, “Refugee Youth Program”; Giberovitch, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations”; Lappin, Redeemed Children; Martz, Open Your Hearts.

-

[34]

Agi Rubin and Henry Greenspan, Reflections: Auschwitz, Memory, and a Life Recreated (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2006), xix.

-

[35]

Giberovitch, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations,” 47.

-

[36]

Bolgar, interview.

-

[37]

Martz, Open Your Hearts, 121–122.

-

[38]

Bolgar, interview.

-

[39]

Mary Palevsky, “Report on Survey of Jewish Refugee Resettlement in Canada for the Canadian Jewish Congress” (Montreal: CJC, October 1949), 2. This report may be found at the CJCCC National Archive.

-

[40]

Bialystok, Delayed Impact, 63.

-

[41]

Sir George Williams College also served as an important communal space for survivors in the postwar period but since it was the official educational arm of the city’s Young Men’s Christian Association, and thus had no formal connection to the Jewish community, it will not be examined here.

-

[42]

For a discussion about this neighbourhood, see Magda Fahrni, Household Politics: Montreal Families and Postwar Reconstruction (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 28–43; Sherry Simon, Translating Montreal: Episodes in the Life of a Divided City (Montreal and Kingston: McGill Queen’s University Press, 2006); William Weintraub, City Unique.

-

[43]

Founded in 1912, the Herzl Dispensary was established to provide medical, dental, and pharmaceutical services to poor and working-class Jews who lived in and around the Main. It was also a place where Jewish doctors and nurses could practise medicine; anti-Semitic policies in the city’s hospitals limited the opportunities available to them. See Michael Regenstreif, Our History of Family Medicine: The Herzl Family Practice Centre and Department of Family Medicine of the Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, 1912–1994 (Montreal, 1994); Gerald Tulchinsky’s review of this booklet in Canadian Jewish Studies 3 (1995): 140–141.

-

[44]

Fischer and Switzer, “Refugee Youth Program,” 39; Lappin, Redeemed Children, 59.

-

[45]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 54.

-

[46]

Younger, interview.

-

[47]

Musia Schwartz, interview, 16 June 2009.

-

[48]

Bolgar, interview.

-

[49]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 55.

-

[50]

Palevsky, “Report on Survey of Jewish Refugee Resettlement,” 17.

-

[51]

Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview; Musia Schwartz, interview by Steven High and Stacey Zembrzycki, Montreal, 24 November 2008. Also see Martz, Open Your Hearts, 52–53.

-

[52]

Musia Schwartz, interview, 24 November 2008. Also see Lappin, Redeemed Children, 61.

-

[53]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 60.

-

[54]

Zoltak, interview.

-

[55]

Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[56]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 61.

-

[57]

After finding a place to live and/or a job, survivors tended to have little contact with the social workers who had been assigned to them. Additional meetings were voluntary and determined by the survivors themselves. See Schwartz, interview, 16 June 2009.

-

[58]

Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[59]

Once her children were both in school, Musia returned to university and eventually earned a PhD in comparative literature from McGill University. See Schwartz, interview, 24 November 2008.

-

[60]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 61.

-

[61]

Ibid., 61–65.

-

[62]

Younger, interview.

-

[63]

Fischer and Switzer, “Refugee Youth Program in Montreal,” 120.

-

[64]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 130–133.

-

[65]

Bolgar, interview.

-

[66]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 130–131.

-

[67]

Zoltak, interview.

-

[68]

Schwartz, interview, 16 June 2009.

-

[69]

“Recreation Programme for New Canadians: November 1, 1948–January 31, 1949,” YM-YWHA of Montreal Memorandum, box 8, Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association Collection, CJCCC National Archive.

-

[70]

Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[71]

Zoltak, interview.

-

[72]

Our Library, 1914–1957 (Montreal: Jewish Public Library, 1957), 79; Naomi Caruso ed., Folk’s Lore: A History of the Jewish Public Library, 1914–1989 (Montreal: Jewish Public Library, 1989); Evelyn Miller, “The History of the Montreal Jewish Public Library and Archives,” Canadian Archivist 2, no. 1 (1970): 49–55. We are thankful to Shannon Hodge, archivist at the JPL, and Eddie Paul, head of bibliographic and reference services at the JPL, for their help in locating these sources.

-

[73]

While many of our interviewees now have a working knowledge of French, few learned it upon arriving in Montreal. When asked about why they had not learned French, most survivors stated that they did not need to know it. They spoke English in their places of employment, which were predominantly Jewish establishments, and either English or their native languages at home.

-

[74]

Krysia, interview.

-

[75]

Olga Sher, interview by Sandra Gasana and Steven High, Montreal, 19 December 2009.

-

[76]

Schwartz, interview, 16 June 2009.

-

[77]

Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[78]

Ibid.

-

[79]

Giberovitch, “Contributions of Montreal Holocaust Survivor Organizations”; Lappin, Redeemed Children, 133.

-

[80]

See Paula Draper, “The Accidental Immigrants: Canada and the Interned Refugees” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 1983); Draper, “The ‘Camp Boys’: Interned Refugees from Nazism,” in Enemies Within: Italian and Other Internees in Canada and Abroad, ed. Franca Iacovetta, Roberto Perin, and Angelo Principe, 171–193 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

-

[81]

Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[82]

Bolgar, interview. Rena and Mayer remember the NWC differently, as a place that moved to different locations around the Main and held social functions every Saturday night. See Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[83]

Bolgar, interview; Rena and Mayer Schondorf, interview.

-

[84]

Bolgar, interview.

-

[85]

Ted Bolgar, interview by Jessica Silva and Stacey Zembrzycki, Montreal, 12 January 2009.

-

[86]

Ibid.

-

[87]

Mayer and Rena Schondorf, interview.

-

[88]

Ibid.

-

[89]

Lappin, Redeemed Children, 137.

-

[90]

Bolgar, interview.

List of figures

Postwar survivor spaces