Article body

David Rohr, of Boston University, has written a highly critical review of my book, Peirce’s Twenty-Eight Classes of Signs and the Philosophy of Representation : Rhetoric, Interpretation and Hexadic Semiosis, from Bloomsbury’s Advances in Semiotics series. As a rebuttal of each of his charges would require a text twice as long as the review, in this reply I shall simply comment at length upon a number of the more damaging criticisms after having referred briefly to a number of others of a similar vein. This will give the reader a good idea of the rather uneven grasp Rohr has of Peircean semiotics, and, at the same time, show that Rohr, willfully or otherwise, has misrepresented, misinterpreted, or simply misread my book.

To begin with, I apparently “err unfailingly” and reach “implausible conclusions” by stating that Peirce abandoned his triadic conception of semiosis for a hexadic one; by claiming that the 1906 definition of the sign is “radically different” from that of 1903; by claiming that by 1906 speculative rhetoric had become “redundant”; and by claiming that intellectual concepts lack objects. I shall take this first group of objections in turn before dealing with more serious charges, and will complete the reply with three comments on the character of the review itself.

With respect to the first point, I maintain that by expanding the original three correlates of 1903 to the six described in the letter to Lady Welby of 23 December 1908 Peirce did base the process of semiosis on six correlates. Prior to 1907 he had not mentioned the concept : in 1903 he simply defined the sign as being determined by its single object in such a way as to determine a single interpretant. The dynamism is implicit here, but by 1908 it had become explicit, and his developing conception of sign action had involved six correlates since 1904. Moreover, the determination sequence defined in the 23 December 1908 letter to Lady Welby (SS : 84-85) – and quoted by Rohr, too – involves six distinct correlates, a sequence which clearly shows the process to be hexadic.

Concerning the two definitions of the sign mentioned by Rohr, readers can judge for themselves :

CP 2.2741903

A Sign, or Representamen, is a First which stands in such a genuine triadic relation to a Second, called its Object, as to be capable of determining a Third, called its Interpretant, to assume the same triadic relation to its Object in which it stands itself to the same Object. The triadic relation is genuine, that is its three members are bound together by it in a way that does not consist in any complexus of dyadic relations… A Sign is a Representamen with a mental Interpretant. Possibly there may be Representamens that are not Signs.

SS 1961906 Draft letter to Lady Welby, 9 March 1906 :

I use the word “Sign” in the widest sense for any medium for the communication or extension of a Form (or feature). Being medium, it is determined by something, called its Object, and determines something, called its Interpretant or Interpretand... In order that a Form may be extended or communicated, it is necessary that it should have been really embodied in a Subject independently of the communication; and it is necessary that there should be another subject in which the same form is embodied only in consequence of the communication.

There are several definitions of the sign to be found in the Lowell Lectures, including others based around the representamen, a term which is not to be found in any of his discussions of signs and sign classes after 1906. The one from 1903 above is based on Peirce’s theory of triadic relations, and defines the sign as a species of representamen. The definition from 1906, however, is no longer triadic, but involves six correlates, rather. Moreover, it defines the object to be an independent “subject”, the embodied form of which is communicated via an immediate object to the sign and subsequently to three interpretants in the course of semiosis, a process which explains how signs acquire the characteristics we perceive or understand them to have. This is to my mind a radical difference from 1903, and heralds the structure of the two grander typologies of 1908.

As for speculative rhetoric’s being made redundant by Peirce’s expanding conception of the object, I repeat part of the argument from the pages referred to by Rohr, as it shows how Rohr has misrepresented my wording :

… what Peirce is saying in the definition [of the sign in 1906, reproduced above] is that from a logical point of view it is the object composed of its partial objects and the relations holding between them that structure the sign. It follows, therefore, that the whole process of semiosis is ‘objective’ in the sense that the sole structuring ‘agency’ in the process is the dynamic object. This conception of sign-action has implications for Peirce’s philosophy of representation, for the speculative rhetoric branch in particular, for it means that a rhetorical component in the traditional sense becomes redundant within this expanded logic, since any inflections produced, even if they originate in some animate agent, can only enter the sign through the structure of the object, if we accept the definitions above and their implications. In other words, any such rhetorical or methodological intention is not ‘added’ to the sign in any way by the utterer, but is part of the form communicated to, or extended in, the sign by the object and thence to the interpretants, most notably to what Peirce, in the draft refers to as the ‘intentional interpretant’. Any rhetorical or methodological intent the sign may convey, then, is, within this exposition of the general theory, already programmed in the complex form extended by the object.

60-61. Italics in the original

What Rohr fails to mention is that I was discussing the traditional conception of rhetoric as being the sphere of influence of an utterer, and that this conception, if we follow the logic of the definitions Peirce gives in 1906, is redundant : from a logical, as opposed to a psychological point of view, there can be no form, of rhetorical import or otherwise, in the sign that doesn’t come from the object. What that object actually is, or rather becomes in the period 1908-1909, and referred to in the passage as the “rhetorical or methodological intent” that the sign conveys, was the topic of my Chapter 5, and will be discussed again below. Clearly, here, as elsewhere, Rohr has not only misrepresented my thought, but, more alarmingly, has also confused logic with psychology and literary and artistic creation.

Furthermore, concerning the hypothesized redundancy of speculative rhetoric itself, Rohr might like to read or reread the letter to William James dated 25 December 1909 in which Peirce outlines his projected System of Logic (EP2 : 500-502). The first two projected Books are described in relative detail. However, “My Book III”, writes Peirce, “treats of methods of research”. And that is all he has to say of Methodeutic (also referred to in earlier texts as “speculative rhetoric”), which in 1903 he had described as “the last goal of logical study […] the theory of the advancement of knowledge of all kinds” (EP2 : 256), for although the extract in EP2 finishes abruptly after this brief reference to Book III on EP2 page 502, the letter itself, in fact, continues in a very conversational mode (see NEM3 : 871-877). Peirce clearly had no details to give of this third Book. Thus, my hypothesis concerning Peirce’s apparent inability to complete the third book is that the development of the three interpretants and the six- and ten-division typologies of 1908 rendered it indeed redundant – a hypothesis certainly, but one that is not without documentary support. As Peirce defined the sign in the extract from 1906 given above, the only form it can receive must come from the object; in short, there is no form or feature in the sign which doesn’t come from the object. Such a situation obviously renders the status of the utterer problematic, a situation which we see from the fact that both utterer and interpreter were given the logical status of “quasi-minds” in 1906 (R793 : 1-2), a situation which Peirce ultimately resolves in 1909 in his discussion of universes of existence in a draft to William James dated 26 February 1909 (EP2 : 492-495), of which more below.

Rohr’s complaint that I claim that intellectual concepts lack objects is further evidence of his misrepresentation or misreading of my text, and I refer him to page 43, where I express my surprise at ‘a remark which, if taken independently of [Peirce’s] attempts in this particular set of notes to use the semiotics as his proof of pragmatism, we would find particularly sibylline : “Of course, many signs have no real object.”’ (R318 : 373, 1907). For Rohr’s information, this is Peirce’s remark, not mine. Moreover, later in the chapter, in a discussion of logical interpretants, I explain with a table as support (Table 2.5 : 72) just why it was that Peirce should have made such a remark in the first place. In 1907 he thought that intellectual concepts had no real object (his term for the dynamic object in this manuscript), but determined three interpretants, the logical, the energetic and the emotional, while an existent sign such as the command “Ground arms!” had a real object, but only an energetic and an emotional interpretant; finally, the least complex sign, a piece of concerted music, for example, had only an immediate object and an emotional interpretant. Within a year he had abandoned this rather strange system and replaced it with the three-universe, six- and ten-division classification systems referred to in the 1908 letter to Lady Welby, in which, of course, every variety of sign, irrespective of its degree of complexity, has a “real” object. In this case, too, Rohr has neglected to read my text properly. Moreover, his efforts to resurrect the logical, energetic and emotional interpretants are a waste of time, as Peirce never mentioned them again, and they are therefore irrelevant to any subsequent typology.

Consider, now, on a more serious level, Rohr’s charge that I was unable or unwilling to give complete classifications of the pictorial illustrations I offered. I will make just two remarks, one terminological, the other more technical. First, it is simply not true that the 28-class typology “proposes six triadic divisions of signs with each division being defined according to Peirce’s universal categories of firstness, secondness, and thirdness” : he should read or re-read the appropriate extract from the letter to Lady Welby (SS : 84-85), where Peirce presents the universes of necessitants, existents and possibles – these are explicitly defined universes, not categories – in order of decreasing complexity as a preface to his dynamic definition of semiosis involving all six correlates. I think we can assume that if Peirce had wanted to base the system on categories he would have mentioned categories, as he continued to discuss phaneroscopy with Lady Welby and William James amongst others well after 1908. He hadn’t abandoned his interest in categories, it is simply that in the letter and drafts to Lady Welby of late December 1908, to mention but these, universes, not categories, are the basis of the classifications.

Now for the technical problem, as evidenced by Rohr’s note 3, which concerns most of the examples that I analyze and classify in Chapters 4 and 5. Rohr’s complaint is that the classifications are not complete. Although he claims that for almost every sign I discuss it is easy to imagine arguments supporting an alternative classification, Rohr declines to offer any. He continues : ‘Moreover, concerning the last six signs discussed, Jappy bluntly asserts that “What their respective interpretants are, or have been, is, of course, impossible to determine”’ (170). While my inability or unwillingness to identify the interpretants in these cases is for Rohr evidence of the weakness of my case for the 28-class typology, his main complaint at this point, however, is that of the thirteen examples classified only four receive complete classifications, concluding that “... on the most generous reading, Jappy provides examples of six of the twenty-eight classes of signs”. To which I add the following extract from his note 3 :

Here, in their order of appearance, are the thirteen signs Jappy classifies with their respective classifications (“?” indicates that the classification is incomplete at this particular division; complete classifications are bolded) :

“Cheyne Walk” concretive-designative-token-categorical-percussive-gratific (33, 117-120).

“A Summer Palace” concretive-?-token-?-percussive-gratific (34, 119-120).

“In My Craft” collective-copulant-type-relative-percussive-gratific (122).

“Figure 4.7” concretive-?-token-categorical-percussive-action producing (127).

“Symbolic Mutation” collective-copulant-token-categorical-percussive-gratific (127).

“Flower Seller” collective-copulant-token-?-?-? (130).

“Untitled Film Still #14” collective-copulant-token-categorical-sympathetic-gratific (133).

“Westward the Course” collective-designative-token-?-?-? (160).

[…]

There are two answers to these complaints; the first is a case of misreading my text once again. I quote from page 117 of my book (italics added) :

We turn now to the task of comparing the hypoicons with the analytic system provided by the hexad of 1908. In what follows, the classification of each sign is not intended to be definitive, as such an exercise could easily become repetitive and jejune, but principally a heuristic for exploring the potential of the system. We begin by examining some of the illustrations from Chapter 1.

Figure 1.3 in Chapter 1, the drawing of Cheyne Walk, was classified as an iconic sinsign.

Clearly, the meaning of the term “heuristic” is the issue here. More generally, as mentioned above, Rohr’s complaints can be summarized as my inability to complete my classifications, an inability indicated by the question marks in the examples from his note. These “?” signs are placed within the classification in some cases, and represent the complete interpretant series in others, e.g. in “Flower Seller” and “Westward the Course…”.

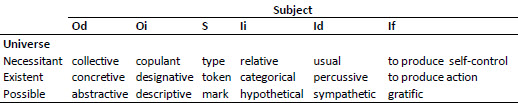

In the first case, I would remind Rohr that when three or more successive subdivisions belong to the same level of complexity, irrespective of whether they are classified according to categories or universes, or whether they are classified according to the system of 1903 or to those of 1908, it is standard practice, introduced by Peirce himself, to omit redundant information. Presumably Rohr would take issue with Peirce for identifying a sign class as a dicent sinsign, and not, as Rohr would presumably wish, as a dicent indexical sinsign, and for identifying a sign simply as a qualisign rather than as a rhematic, iconic, qualisign. In my classifications, for example “At the Summer Palace” and Figure 4.7, in Rohr’s note 3, I omitted to mention the existent immediate object subdivision label “designative”, since a sign already classified as a concretive and subsequently as a token makes such a mention redundant, and such a situation was clearly visible on my Tables 3.2 (82) and 4.2 (118), reproduced here as Table 1. (Note that this ‘horizontal’ format is not one Peirce ever employed.)

Table 1

The Six-Division, 28-Class System Set Out across the Page

I prefer to follow Peirce’s lead in such matters, thereby avoiding potentially jejune sequences of unnecessary information. Rohr might like to reread CP 2.254-2.264 to see in which cases Peirce omits redundant information.

Rohr’s questioning of the absence of classification concerning interpretant sequences is altogether more alarming. Just supposing, in answer to this particular charge, I had included in my reply a photograph of the palm trees in my back garden – I live in the south of France – Rohr would surely admit that it would be impossible for me to anticipate any reader’s reactions : envy, disdain, indifference? Verbal reactions such as “The photo is very grainy”, “Those aren’t palm trees, they’re Aleppo pines”, or “He’s just boasting”? There might even be no spoken reaction at all. How should I know? As I say in the text, and as I maintain here, if a photograph or utterance – any sign used as an illustration – has been placed in a text and published, it is impossible to determine in advance what the reactions, i.e. the interpretants, will be : these, I maintain, are anybody’s guess. This being the case, I omitted to speculate on what the interpretants of these particular images might or might not be, assuming the reader to be capable of understanding why. I should have thought that such an assumption would be self-evident to any reader, but obviously I was wrong.

This discussion of the interpretant sequences leads me naturally to deal with an important charge made by Rohr concerning the differences between the 1903 and the 1908 typologies. Like other criticisms in his review, this tends to show that he is unaware of the fact that Peircean semiotics is a form of logic, and has nothing to do with psychology, linguistics, literary or artistic creation, literary criticism or the sort of semiological analysis practiced by Barthes and others, any more than do the propositional and predicate calculi. If I understand him, he claims that in addition to dismissing “through inscrutable paths” the influence on their signs of speakers, writers and artists, I’ve failed to justify my assertion that the two systems are very different, and that in fact there is no reason to suppose that the second yields any more useful information than the first. Rather than quote large parts of my Chapters 4 and 5 concerned precisely with this problem, I have simplified by borrowing an example from a recent article published in an excellent Chinese semiotics journal (Jappy 2016 : 26). Consider the italicized sentences in the following extract from a detective novel :

Wylie smiled, brought the car in to the kerbside and pulled on the handbrake. Hood opened his door a fraction and peered down. ‘No’, he said, ‘this is fine. I can walk to the kerb from here’. Wylie gave his arm a thump. He suspected it would bruise.

Rankin 2000 : 196

Rohr would admit that all three – indeed, all the sentences in the extract – are to be classified within the 1903 ten-class system as undifferentiated dicisigns, for they all are replicas of dicent symbols, irrespective of their very different syntax and lexical content. And yet we know that this relational classification tells us nothing of their communicative purpose, which we nevertheless understand clearly as we read the book to be a teasing remark followed by a robust reaction from the addressee. Contra Rohr, the 1908 system provides us with a more appropriate analytical approach to the semiosis represented here, namely an a posteriori analysis of the interpretant sequence, which enables us to explain within a logical framework why the first two sentences were uttered and what the effect that they produced was.

The first two italicized sentences – manifesting the immediate object and the airwaves of the sign-medium – are ironic : by experience we understand the speaker to be deliberately mocking the poor parking skills of his colleague. The third describes an action from which we as readers infer that at the immediate interpretant stage the ironic intent of the first two utterances – this intent being the sign’s necessitant dynamic object – has been understood by the interpreter. The dynamic interpretant is existent, thereby conditioning the final, which is realized here emphatically as the action of the thump on the arm. Such an analysis thus involves following a sequence of actual reactions or effects – interpretants, in other words – as they are determined by a given sign.

The italicized items are, as mentioned before, a sequence of dicent symbols within the ten-class system, and as instances of action-producing, categorial, collective types within that of 1908. Since we are dealing with instances of types, the dynamic and immediate objects must also be necessitant : the immediate is the complex syntax and intonation characterizing each communicated form, while the dynamic is the ironic intention of the speaker. Pace Rohr, what is of interest here is not so much a complete classification of these utterances as the use of the 1908 system as a heuristic device, and I continue to claim that the 1908 analysis has greater heuristic potential and must surely, when understood, be recognized as more informative.

This leads me to a related objection of Rohr’s, namely, that my final chapter is as disjointed as its title “Interpretation, Worldviews and the Object”; this enables me, at the same time, to dismiss Rohr’s indignation at my neutralization of the influence on the signs they produce of speakers, writers and creative artists of all kinds. The chapter begins with a recurring problem of interpretation, namely cases where interpreters have claimed that what is in a photograph, say, is not the real object of the sign, suggesting, on the contrary, that the real object is somehow other, somehow more general than the objects visible in the image. One example I offer is from Hariman and Lucaites’s No Caption Needed (2007), in which the authors suggest that a photograph of the Kent State University massacre of 1970 represents something far more general than a screaming female student kneeling beside the body of her dead comrade, namely, the ideological tension between individual rights and collective obligations – between “the concepts of democratic citizenship and dissent” (Hariman & Lucaites 2007 : 48).

The rest of the chapter is devoted to exploring the implications of the important late development of Peirce’s object for the discussion of this sort of interpretation problem, a topic Rohr presumably considers unworthy of comment. And yet. Consider some of the following prophetic examples of the sorts of entities that can be necessitant, and, therefore, general, unperceivable objects, and, in my square brackets, some of the contemporary research fields that they anticipate :

The third Universe comprises everything whose Being consists in active power to establish connections between different objects, especially between objects in different Universes. Such is everything which is essentially a Sign… Such, too, is a living consciousness, and such the life, the power of growth, of a plant [biosemiotics and phytosemiosis]. Such is a living institution, – a daily newspaper, a great fortune, a social “movement” [biosemiotics and anthroposemiosis].

CP 6.455, 1908

To these can be added from a draft to William James two months later this very important late statement concerning the object :

The Object of the Command “Ground arms!” is the immediately subsequent action of the soldiers so far as it is affected by the molition expressed in the command…You may say, if you like, that the Object is in the Universe of things desired by the Commanding Captain at that moment. Or since the obedience is fully expected, it is in the Universe of his expectation.

EP2 : 493, 1909

Here Peirce has replaced the quasi-minds of 1906 by a sophisticated and prescient integration of non-psychological purpose in the logic : although he doesn’t phrase the problem in this way, his late theory of the object, allied with the hexadic process of semiosis, offers the means of distinguishing logically between intention in living organisms and physical causation in the case of inanimate agencies. Since in Peircean logic semiosis is always initiated by the object, necessitant objects such as those mentioned above are exponents of intention whereas existent objects are exponents of causation. For example, in the case of the teasing, ironic remark from the detective novel discussed earlier, it is surely better from a semiotic, i.e. from a purely logical point of view, to see the initiation of this particular semiosis as a case of intention rather than to get involved in discussions of character motivation from the standpoint of literary theory or psychology, these being special, idioscopic sciences in Peirce’s classification (EP2 : 260-262, 1903). This seems to me to be a considerable advance in Peirce’s thinking on logic and, contra Rohr, worth investigating further – as the biosemioticians have been doing for over half a century. Although the book devotes half of Chapter 4 and the whole of Chapter 5 to these issues, the discussion above briefly answers the following charges of Rohr’s, who clearly hasn’t read the book he’s reviewing very thoroughly :

What does the division based upon dynamic objects help us to understand about the signs it classifies? How does it illuminate processes of semiosis in which signs belonging to that class are being interpreted? What confusions does this classification help us avoid? What further inquiries does it prompt? Jappy’s defense of the 28-sign classification never broaches these basic justificatory questions.

In another comment, Rohr quibbles with my standardizing the explicit interpretant in Peirce’s letter as the final interpretant, preferring David Savan’s suggestion that the explicit is in fact the immediate. I won’t repeat my arguments in the book but will simply add the following remarks. We know from the passage that the order of determination given by Peirce in the letter is phrased as follows : … sign → destinate interpretant → effective interpretant → explicit interpretant (SS 84-85). Rohr suggests, as did Savan and others, that the explicit in this case corresponds to the immediate. This is untenable for two reasons. First, if the sign determined the final interpretant before it determined the immediate, it is difficult to imagine how the final might determine its own interpretability since, from a logical point of view, the interpretability of the immediate must precede and determine the final. In other words, how could an action-determining sign with an existent final interpretant, for example, produce an action by some agent-interpreter before it has been understood at the interpretability-immediate interpretant stage by that agent? How, returning to the example from the detective story, could the final thump on the arm possibly precede the immediate realization that the speaker was being ironic? Second, if Rohr had looked carefully at my Table 3.3 (92) he would have seen that the only two typologies to employ the order final + dynamic + immediate of the thirteen classifications displayed thereon were both from 1904, an order which Peirce never again employed in subsequent typologies. From 1905 on, all the typologies had, in the interpretant sequence, immediate + dynamic + final or their terminological equivalents, which is what one would expect – final, as in “last item in a series”.

I turn now to Rohr’s reworking of Peirce. At this point, it has to be said, the bruising the ego experienced on reading that the only part of the book that is of scholarly interest is to be found in the appendix suddenly becomes a thing of the past, for Rohr subjects Peirce’s original statements on signs and typologies to the same misinterpretation, misunderstanding and misreading as he does my book. There are several examples of this in the review, but I will simply discuss various instances of his crusade to render the original systems more efficient. These involve Rohr’s questioning the theoretical value of some of the important concepts, and even excising them from Peirce’s semiotic systems in order to eliminate what he presumably sees as noise or redundancy. For example, following the problem of the explicit interpretant discussed above, he writes :

Whether one agrees with Jappy or Savan on this peripheral issue, I think both the final interpretant and the immediate object are problematic given the order of determination posited by Peirce. Beginning with the final interpretant, assume first that Jappy is correct and that the order of determination–where (X → Y) means “X determines Y” – is : (sign → immediate/destinate interpretant → dynamic/effective interpretant → final/explicit interpretant). How does the dynamic interpretant determine the final interpretant?

The answer to this is simple : dynamism is a precondition to action, since a sign classified according to the existential nature of the final interpretant is an action-producing sign. I give an example of this in the extract from the mystery novel quoted above : the very existential thump on the arm – which is the action produced, the sign’s final effect in that particular semiosis – logically presupposes an equally existent dynamic interpretant. Consider another example : if the telephone rings as I write this, I pick it up. The actual action of answering the phone is the final interpretant, but it necessarily involves the dynamic physical exertion of grasping it that follows my understanding that someone wants to communicate with me.

Rohr goes on to examine the effects of adopting Savan’s order instead of mine, and comes up with the following theoretical “improvements” to Peirce’s original conceptions : “Once again, it seems better to say that the final interpretant is determined, not by the sign, but by the dynamic object”, this from a reviewer who takes me to task for suggesting that the 1906 definition of the sign reduces its erstwhile dominant status in the determination sequence! Were what Rohr suggests the case, we should have a dyadic relation between two entities which, without a mediating sign, would simply not qualify logically for dynamic object and final interpretant status. Behind this lurks a nostalgia for the simplicity of the 1903 system, which the later systems seem to threaten. For Rohr goes on in a later paragraph to claim that : “In addition to the final interpretant, it seems to me that the role of the immediate object in Peirce’s determination sequence is also highly suspect”, adding later “what sense does it make to assert that : (dynamic object → immediate object → sign)? If the claim were only that (dynamic object → sign), that would be relatively intelligible.” The reader might be thinking that Rohr’s solution to this non-problem is to return to the security of the well canvassed 1903 ten-class typology, with its single object and single interpretant. However, as this extract from his note 4 clearly shows, there is more paring-down that needs to be performed :

I expect that the attempt to defend [Peirce’s 1908] complex determination sequence will fail and that the only determination sequence that will remain plausible is that (dynamic object → dynamic sign → dynamic interpretant). (By a dynamic sign I mean an actual sign–a physically real, dynamically reactive entity that actually possesses the capacity to represent an object and that is actually interpreted as representing that object by some interested interpreting organism.)

The departure from Peirce’s original semiotic thinking is drastic : a single existent sign, determined by a single existent object determines in its turn a single existent interpretant – in one fell swoop Rohr has dismissed the continuity of thought from Peircean semiotics. Dismissed, too, are the conceptual advances of the types of necessitant objects from 1908 and the 1909 draft to James. This represents a regression to a sort of cramped nominalism. But there is more, as Rohr suggests in the note that we reduce even the ten classes of 1903 to just six by amputating from the 1903 system the division identifying qualisigns, sinsigns and legisigns :

If my guess is right, then a much simpler classification system will be sufficient. In accordance with that classification, and contra the 28-sign and 66-sign classifications, I doubt that the category of either the dynamic object (possible, existent, necessitant) or the dynamic interpretant (emotional, energetic, logical), considered in and of themselves, provides a basis for an important division of signs. (This is not to deny that they constitute important divisions of objects and interpretants.) Moreover, the division based upon the category of the sign itself, which divides signs into qualisigns, sinsigns, and legisigns is also doubtful, if for no other reason than that qualisigns and legisigns require sinsigns in order to represent (EP 2.291). My best guess is that only relational questions concerning how the sign is capable of representing its object (icon, index and symbol) or how the sign appeals to its interpretant (rheme, dicisign, argument) mark important divisions of signs. Assuming only these two divisions from the 1903 10-sign classification results in a classification with only six signs : iconic rheme, indexical rheme (degenerate index), indexical dicisign (genuine index), symbolic rheme (term), symbolic dicisign (proposition), and symbolic argument. I hope to explore this simpler classification in a future essay.

Rohr was apparently not aware of this, but if he was, he should have mentioned it, for his two suggested divisions correspond exactly to Peirce’s initial attempt at a typology in 1903. This appears in manuscript R478, where, after setting out the phenomenological basis of the definitions to come, Peirce states “[Signs] are divisible by two trichotomies” (EP2 : 274). However, as he subsequently realized in his discussion of triadic relations (EP2 : 289-291), it makes no sense to attempt to classify signs according to the phenomenological complexity of the relations holding between them and their correlates without having first established the phenomenological status of the sign itself, which is what the qualisign, sinsign, legisign division accomplishes. We see the importance of this in Peirce’s conception of the index : the degenerate indices of 1903 were verbal in nature, and differed from the genuine by being, not sinsigns, but legisigns. If we excised the sign division as Rohr suggests it would be impossible to differentiate logically between a demonstrative pronoun and the veering of a weathercock. Not really a theoretical advance, this. In fact, Rohr’s suggestions for improving Peirce’s concepts and classifications put one irresistibly in mind of Chomsky’s acerbic dismissal of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior : “a kind of play-acting at science” (1959 : 39).

I should like to finish this reply by discussing three recurrent features of the review qua review. One point concerning the review itself which merits censure is Rohr’s repeated unsubstantiated negative dismissals of aspects of my work. As an example, consider anew part of Rohr’s summary of my Chapter 5 :

The fifth chapter, “Interpretation, Worldviews and the Object”, is as disjointed as its title. The first half of the chapter is focused on Peirce’s concept of the object and reveals Jappy at his most confused. Through inscrutable paths, Jappy brings himself to the incredible conclusion …

That Rohr should find fault with this and any other conclusion in my work is entirely acceptable in a review. That is what a review is for : a reasoned examination of potential weaknesses and points of general interest in the work under review. What is less acceptable, however, is the accumulation of value judgments of the unsubstantiated “disjointed”, “confused” and “inscrutable” sort, which, in addition to many others in an attempt to project the reviewer as authoritative and uncompromising, border on the ad hominem.

A second point concerns Rohr’s several very dubious arguments from authority, citing principally Albert Atkin and T. L. Short. It is not because these two Peirce scholars have found the late systems rambling and incoherent that others shouldn’t investigate them. Consider, in this respect, the following statements from Rohr’s dismissal of my wishing to investigate a typology that Peirce seemingly only mentioned once, in the 1908 letter to Lady Welby :

If this is the first and last time the 28-sign classification is mentioned by Peirce, why should we care about it or think it is worthy of in-depth study? It seems to me that anyone who closely examines the proliferation of inconsistent classifications developed between 1903-1910 must at least sympathize with Atkins’ [sic] and Short’s characterization of this flurry of late “systems” as “speculative, rambling . . . incomplete”; “sketchy, tentative, and . . . incoherent” (Atkins [sic] 2010 : para. 2; Short 2007 : 259-60). In my opinion, all of Peirce’s a priori, category-driven classifications–the 66-sign, 28-sign, and 10-sign classifications–should be regarded as on probation until they receive more convincing a posteriori justifications.

To which I reply that only by trying to give the universe-driven, 28-class typology an a posteriori justification, that is, by attempting to assess its exploratory power as I have tried to do irrespective of what Atkin and Short might think of such an enterprise, will it be possible to advance our knowledge and understanding of Peirce’s late semiotic systems. These are characterized by Rohr himself as “the proliferation of inconsistent classifications developed between 1903-1910” and as requiring to be regarded as “on probation” (the well-established1903 ten-class system included!), until justified by later research – such as mine, perhaps. Dismissing them as rambling and incoherent, as Atkin and Short apparently recommend that we should, doesn’t seem to me to advance our understanding of them. And for Rohr’s information, in concentrating on the larger typology Peirce didn’t neglect the 28-class system, since by attempting to establish the ten divisions of the 66-class typology in the letter of December 23 and the drafts of December 25 and 28 he was necessarily integrating the six divisions of the former. And this, I might add, is not an “arbitrarily truncated” version of the 66-class system as Rohr alleges elsewhere in his review : on the contrary, it seems far more appropriate from Peirce’s statement to affirm that the 66-class typology is really no more than the 28-class typology expanded to include four more divisions.

Finally, the most disturbing aspect of the review is not that Rohr should resort to such unacceptable rhetorical techniques as authority and ad hominem arguments and a Sophist deference to the opinion of the many, but that he should dismiss out of hand the value of undertaking the sort of research that is represented in the book in the first place. He seems to think that a research project is only worth investing time and energy in if one is sure of its value or if some “authority” has cautioned the undertaking. But, of course, as Houser’s research programme mentioned in the book attests, if we don’t know the value of Peirce’s late semiotics now, this is good reason to investigate whether it has any. People don’t only undertake research because they or others think it to be profitable – some also do so to see what they might find.

Appendices

Bibliography

- CHOMSKY, N. (1959) Review of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. In Language (35) : 26-58.

- HARIMAN, R., & LUCAITES, J. L. (2007) No Caption Needed : Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago : The University of Chicago Press.

- JAPPY, T. (2016) “The Two-Way Interpretation Process in Peirce’s Late Semiotics : A Priori and a Posteriori”. In Language and Semiotic Studies (5)2 : 14-30.

- PEIRCE, C. S. (1931-1958) The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, 8 Volumes. C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss, and A. W. Burks (Eds.), Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press. (CP)

- PEIRCE, C. S. (1976) The New Elements of Mathematics, Volume Three : Mathematical Miscellanea (2 Volumes), Eisele, C. (Ed.), The Hague : Mouton. (NEM3)

- PEIRCE, C. S. (1998) The Essential Peirce : Volume 2. Peirce Edition Project (Eds.), Bloomington : Indiana University Press. (EP2)

- PEIRCE, C. S., & WELBY-GREGORY, V. (1977) Semiotic and Significs : The correspondence between C. S. Peirce and Victoria Lady Welby. C. S. Hardwick (Ed.), Bloomington : Indiana University Press. (SS)

- RANKIN, I. (2000) Set in Darkness. London : Orion Books.

List of tables

Table 1

The Six-Division, 28-Class System Set Out across the Page