Abstracts

Abstract

In the summer of 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in the Hague ruled on a territorial dispute between the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over the South China Sea (SCS). In brief, the PCA found the claims of the PRC over most areas of the South China Sea illegitimate and therefore did not recognize the PRC’s claim of territoriality over these waters. In this case note, I explore the details of this PCA case, through a close analysis of the relevant case documents. I conclude the note by looking at different precedents set by this particular case. To do so, I also briefly turn attention to the relevant legal concepts of maritime law and the mechanisms for maritime dispute settlement, provided for in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In doing so, I identify how these legal concepts come into play in this particular case and explore its possible implications on future cases of maritime dispute settlement.

Résumé

À l’été 2016, la Cour permanente d’arbitrage (CPA) de La Haye s’est prononcée sur un différend territorial entre les Philippines et la République populaire de Chine (RPC) concernant la mer de Chine méridionale. En résumé, la CPA a jugé les revendications de la RPC sur la plupart des régions de la mer de Chine méridionale illégitimes et n’a donc pas reconnu la prétention de la RPC à la territorialité sur ces eaux. Dans cette note de jurisprudence, j’explore les détails de cette affaire en analysant de près les documents pertinents du cas. Je conclus la note en examinant différents précédents établis par ce cas particulier. Pour ce faire, j’attire également brièvement l’attention sur les concepts juridiques pertinents du droit maritime et sur les mécanismes de règlement des différends maritimes, prévus dans la Convention des Nations Unies sur le droit de la mer (CNUDM). Ce faisant, j’identifie la manière dont ces concepts juridiques entrent en jeu dans ce cas particulier et explore ses implications possibles sur les futurs cas de règlement des différends maritimes.

Resumen

En el verano de 2016, la Corte Permanente de Arbitraje (CPA) de La Haya falló sobre una disputa territorial entre Filipinas y la República Popular China (RPC) respecto al mar del Sur de China. En resumen, la CPA consideró ilegítimos la mayoría de los reclamos de la RPC y, por lo tanto, no reconoció su reclamo de territorialidad sobre estas aguas. En este análisis de la decisión, exploro los detalles del caso analizando detenidamente los documentos relevantes. Concluyo la nota examinando los precedentes establecidos por este fallo. Para ello, llamo brevemente la atención sobre los conceptos jurídicos relevantes del derecho marítimo y los mecanismos para la solución de controversias marítimas previstos en la Convención de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Derecho del Mar (CNUDM). También identifico cómo estos conceptos legales interactúan en este caso particular y exploro sus posibles implicaciones para la resolución de futuras disputas marítimas.

Article body

The South China Sea (SCS) has often been a hotbed for territorial disputes. The SCS lies in the middle of several important international shipping routes, which is part of the reason that most of the States neighbouring the SCS hold steadfast to their territorial claims over what they consider their part of this sea. In recent years, the discussion surrounding territorial claims over the SCS has once again flared up. Specifically, a newly discovered map[1] showing the now-famous ‘nine-dash line’ led to new assertions of sovereignty by the People’s Republic of China (PRC).[2] According to the PRC, these maps prove that portions of the SCS and islands in that portion are within its territorial sea. This claim puts the PRC at odds with other States, who also claim certain sovereign rights or full sovereignty over parts of the SCS. The territorial claims tend to overlap, leading to territorial disputes (see image 1, infra).

Image 1

Relying on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) dispute-settlement provisions, the Philippines decided to take its dispute with the PRC concerning the SCS to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), which has its seat at the Hague. During the proceedings, different legal arguments were brought forward by both parties. The nature of the dispute, the status of the relevant maritime areas and the status of the islands concerned were all called into question in the arbitration. In fact, the PRC also debated the validity of using mandatory UNCLOS dispute-settlement procedures in this particular dispute.

In this case note, I seek to dissect the core legal arguments of the case. To do so, it is imperative to understand the background to the case. Hence, I first turn my focus to the relevant international-law concepts enshrined in the UNCLOS. Then, I apply these concepts to my review of the SCS case by looking at three matters: (a) the historic background of the case, (b) the arguments brought forward during the case proceedings and the award and (c) precedential value of the case, i.e., the implications of the arbitral proceedings on the future of the SCS dispute and maritime dispute settlements in general. For the discussion of the case, an extensive analysis of relevant case documents was performed, though I also focus on other relevant legal literature and case law for the discussion of the possible implications of the SCS case.

I. A Brief Primer on UNCLOS: Maritime Zones, Maritime Features and Dispute Settlement

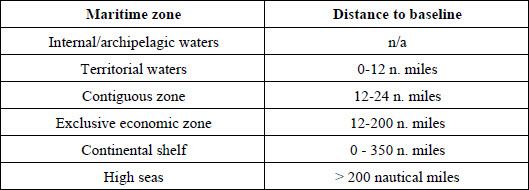

An important aspect of understanding disputes in maritime delimitation is grasping the nuances of the legal definitions for maritime zones provided in the UNCLOS. This treaty created a universally applicable standard for the breadth of the territorial waters, established compulsory procedures for maritime dispute settlement and specified the rights and obligations for States with regard to the high seas and maritime travel.[3] This treaty is often seen as a ‘constitution of the oceans’: a written document, legally binding on all the signatory States.[4] It has, furthermore, created three new institutions to support the enforcement and arbitration of international maritime law: the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).[5] The treaty also contains a provision that generally prevents States parties from having reservations on parts of the treaty, meaning that the State parties cannot opt out of certain elements of the treaty.[6] As I will discuss in detail later on, this last point in particular has become an important element of contention in the SCS case.

The rights and duties of a coastal State in a given body of water depend on what maritime zone the water falls under. UNCLOS specifies the different zones based on their distance from “baselines”, which is generally the line drawn along the exact position where the land meets the water at low tide: the so-called “low-water line”.[7] The different zones are internal waters, territorial waters, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the high seas. In accordance with UNCLOS, States are allowed to claim up to 12 nautical miles of sea (from the coastal baseline) as their territorial waters. Territorial waters fall under State sovereignty and are an integral part of a State’s jurisdiction. This fact means coastal states are allowed to exert criminal jurisdiction over commercial ships in their ports or territorial waters. The same degree of territorial sovereignty applies to archipelagic waters. An archipelago is defined here as a group of islands and the water between it, which forms an “intrinsic geographical, economic and political entity.”[8] Coastal states are, however, not allowed to extend their legislative jurisdiction over the adjacent contiguous zones: there they can only punish or prevent infringements of its sanitary, fiscal or migratory regulations.[9] In the EEZ, coastal States can only claim those sovereign rights that are explicitly mentioned in the UNCLOS:

-

Rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil;

-

Rights with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds.[10]

Table 1

The Different Maritime Zones (UNCLOS)

It is to be noted that sovereign rights are of a more limited nature than territorial sovereignty.[11] Connected to this state of affairs is the concept of “continental shelf”, a landmass below the seas that is generally seen as a natural extension of the land. States cannot unilaterally decide to extend their continental shelf beyond their EEZ, but have to prove, by means of scientific data, that an extension exists to the CLCS.[12] The relevance of this obligation is that the sovereign rights of a coastal State to exclusively explore the continental shelf and exploit its natural resource extend to this shelf.[13] Lastly, UNCLOS defines the high seas as all areas of the sea that are neither part of the EEZ, nor part of territorial or archipelagic waters.[14] As opposed to the other zones, the high seas are governed by the principle of the freedom of the high seas, meaning that ships should be able to freely navigate the high seas without unwarranted attacks from other vessels.[15] The high seas are res nullius: a thing belonging to no one. Hence no state can claim sovereignty over them.[16] This rule also applies to the soil under the high seas, which means that no state is allowed to mine resources in the high seas without the consent of the International Seabed Authority (ISA).[17]

A subject debated in international maritime law is the status of land areas (or maritime features) in Earth’s oceans. These areas or features are divided into different types, the first of which is islands. UNCLOS dictates that to be considered an island, a maritime feature should meet the following requirements: (1) it is a naturally formed area of land, (2) surrounded by water, (3) which is above water at high tide.[18] Islands, notably, have their own territorial waters, contiguous zones, EEZs and continental shelves, increasing the size of a coastal nation’s territory.[19] If such a feature does not meet the first criterion of being naturally formed, then it is considered to be an artificial island. Artificial islands do not enjoy a territorial sea, EEZ or continental shelf of their own.[20] Also, if a maritime feature “cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own”, it is legally seen as rocks.[21] Rocks do not enjoy an EEZ or continental shelf either.[22] If a feature does not meet the third criterion of being above water at high tide, it is considered to be at low-tide elevations. Unlike with rocks, coastal States can use low-tide elevations for drawing baselines, provided they are inside the boundaries of their territorial sea.[23]

As mentioned above, UNCLOS provides for compulsory procedures for settling international maritime disputes: in the ITLOS, the ICJ, an arbitral tribunal or special arbitral tribunal in accordance with the Annexes VI, VII and VIII of the UNCLOS respectively.[24] In the case of the SCS, the Philippines opted for instituting proceedings before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) as per Annex VII. This particular choice of procedure by the Philippines is one of the crucial arguments for the PRC. Before turning to the arguments of the case, however, I would like to briefly discuss the background of the dispute.

II. The Background of the SCS Dispute

After World War II, former Japanese territories were placed under the ‘trusteeship’ of the Republic of China, led by Chiang Kai-Shek, but without specifically naming the territories as SCS territories.[25] In 1948, the government of the Republic of China was deposed and ‘exiled’ to the island of Taiwan by the communist revolutionary forces, led by Mao Zedong. In 1952, a peace treaty was brokered in which Japan transferred sovereignty over Taiwan, the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands to the government of the Republic of China (now operating from Taiwan).[26] Since the PRC also claims sovereignty over Taiwan, it therefore sees Taiwan’s claims and possessions as the PRC’s. This position stems from the ‘one China policy’, in which political leaders of Taiwan and China avoid conflict between the two by acknowledging that there is only one legitimate China, without specifying which one of the two it is.[27] Despite this, there have been international disagreements on who has ownership of islands in the area (the Paracel Islands, the Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoal).[28]

Several events ultimately led to the Philippines lodging a case at the PCA in 2016. First, the Philippines has claimed State sovereignty over all maritime features within their sovereign seas since 1949. With the Republic Act No 3046 of 1961, the Philippines drew its baselines and thus explained exactly what waters it considered its waters. Secondly, the Philippines also claims that it had built up a clear presence and effective control over these islands over the years. According to the Philippines, when Filipino soldiers occupied the islands in the 1960s, the islands were uninhabited and unused by third parties. As such, it sees the subsequent incursions on the islands as breaches of its territorial sovereignty. Thirdly, the Philippines bases its claim on its geographical proximity to the Spratly Islands. This claim is supported by the fact that the closest islands are less than 100 nautical miles away from the Filipino coastline, and thus overlap with the Filipino EEZ. The fourth fact that the Philippines has pointed to is that China had recently aggravated the dispute between the two States, by building artificial islands in the disputed waters and forcibly barring Filipino ships from entering the disputed territories.[29]

To understand the Chinese position in this case, it is imperative to look at the events directly leading up to the proceedings. The first assertion made by the PRC relating to the islands in the SCS is found in the 1958 Declaration of the Government of the PRC on China’s territorial sea, where China specifically refers to the Nansha Islands as belonging to China, even though they might be “separated from the mainland and its coastal islands by the high seas.”[30] Later, in 1996, the PRC signed both UNCLOS and the agreement for implementing Part XI (containing the dispute settlement mechanisms).[31] In accordance with Article 310 of UNCLOS, the PRC government in 2006 made a declaration to the United Nations, stating that it: “does not accept any of the procedures provided for in Section 2 of Part XV of the Convention with respect to all the categories of disputes referred to in paragraph 1 (a) (b) and (c) of Article 298 of the Convention.”[32] The Convention states that States are allowed to make additional declarations, but only “provided that such declarations or statements do not purport to exclude or to modify the legal effect of the provisions of this Convention in their application to that State.”[33] Whether or not this provision also applies to China’s declaration is a question that remains debated as of this day.

In 2007, the PRC allowed the province of Hainan to set up a new city in the SCS called Sansha, which now administers both the Spratly and Paracel Islands and the Scarborough Shoal.[34] Shortly after, in 2009, China sent the UN a verbal note,[35] stating that it disagreed with the submissions that the Philippines and Vietnam had made earlier to the United Nations special commission on these matters: the CLCS. In its note, China stated that its claims over their continental shelves overlapped with islands and waters over which China had traditionally had “undisputable sovereignty”.[36] In this same letter, the PRC provided the UN Secretary-General with a map of the territories and waters over which it considers itself to have sovereignty. This was the same map that contained the famous nine-dash line (image 1, above). This was a resubmission of a Taiwanese maritime map from 1948, although some scholars argue that the origins of this maritime delimitation line go further back.[37] In 2011, the PRC sent a second letter to the UN, reiterating its position that it had sole sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. In this second letter, however, the PRC also explained that the Philippines had never, in any multilateral treaties, asserted any claim to the islands, while the PRC did refer to the islands as being under its jurisdiction in several of its international documents. This state of affairs led the PRC to three conclusions. First, that the islands had been effectively controlled and sovereignty claimed by China consistently over time, granting it historic rights over them. Secondly, that the islands had been invaded illegally by the Philippines in the 1970s, meaning that the Philippines could not claim sovereignty from its actions (on the basis of the ex injuria jus non oritur principle). And thirdly, that “under the legal doctrine of la terre domine la mer, coastal states’ claims as to Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and Continental Shelf shall not infringe upon the territorial sovereignty of other states.”[38] This last point shows one of the main legal arguments for the PRC during these proceedings: that it had traditionally claimed sovereignty over these islands (or marine features) and could therefore claim sovereign waters in the surrounding area of the sea as well.

Non-claimant States have also expressed stakes or views in the case. Taiwan claims ownership over the Spratly Islands, on the basis of occupation and historical use since the times of the ancient Ming Dynasty and the 19th century Qing Dynasty.[39] Invoking historic rights, Vietnam also claims ownership over some of the islands and has started occupying islands in the western parts of the SCS.[40] Similarly, Malaysia and Brunei have stated that they have ownership of the southern parts of the seas, based on their proximity to the maritime features or based on the fact that these features are in their EEZ.[41] The US has also spoken out against the fact that the Chinese government has started building artificial islands on maritime features, with US officials likening these efforts to a “great wall of sand.”[42]

It was precisely to prevent international disputes like this that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was founded in 1967. This body gave the nations of the region a platform for multilateral talks and agreement and allowed them to create the multilateral Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC).[43] Although the PRC has never joined the association, it acceded to the TAC in 2003, thus becoming bound by the rules for co-operation and peaceful settlement named in the TAC. However, the difficulty with enforcing peaceful settlement, required under both TAC and UNCLOS, is that there is a strong consensus amongst States in general that international law and judicial dispute settlement should be seen as a last resort, rather than a regular alternative to diplomatic negotiations.[44]

Regarding their dispute in the SCS, the Philippines stated that despite these talks, the PRC would not be persuaded to cease their reclamation efforts in the SCS. The Philippines later on stated,

[O]ver the course of the past 20 years, China has seized physical control of maritime features in the South China Sea that fall within the EEZ and continental shelf of the Philippines. It has also constructed installations upon them and acted in a manner calculated to methodically consolidate control over huge portions of the South China Sea.[45]

The Philippines’ written submission goes on to point out that over the past few years, Filipino fishermen have been chased away from the Scarborough Shoal by Chinese warships, preventing the Philippines from enjoying the right to exploit the natural resources within its EEZ. According to the Philippines, these Chinese military actions are in direct contravention of UNCLOS, which provides that military actions and sometimes even innocent passage by warships are not allowed in another State’s EEZ. The written submission finally states that Philippines had tried to dissuade the Chinese government from its actions by diplomatic negotiations in ASEAN and in bilateral talks, but that the Chinese actions were increasingly assertive of Chinese sovereignty claims over the SCS.[46] It is because of the failed negotiations at ASEAN level that the Philippines resorted to an international arbitration procedure, in absence of a diplomatic alternative to protect its rights over its EEZ vis-à-vis the PRC.

III. Proceedings of the Philippines v China Case

On 22 January 2013, SCS-case proceedings began, when the Philippines sent its Statement of Claim to the PCA. It did so in accordance with Articles 286, 287 and Annex VII of UNCLOS, which govern compulsory procedures entailing binding decisions. Article 287(1)(c) allows States to call for the formation of “an arbitral tribunal in accordance with Annex VII”. The Philippines sought rulings in three matters. It petitioned the PCA to decide as follows:

(1) declares that the Parties’ respective rights and obligations in regard to the waters, seabed and maritime features of the South China Sea are governed by UNCLOS, and that China’s claims based on its “nine dash line” are inconsistent with the Convention and therefore invalid;

(2) determines whether, under Article 121 of UNCLOS, certain maritime features claimed by both China and the Philippines are islands, low tide elevations or submerged banks, and whether they are capable of generating entitlement to maritime zones greater than 12 M; and

(3) enables the Philippines to exercise and enjoy the rights within and beyond its economic zone and continental shelf that are established in the Convention.[47]

The response made by China was brief, but clear. The PRC saw no need to start the proceedings and maintained that “both sides had agreed to settle the dispute through bilateral negotiations and friendly consultations.”[48] Despite this response, the Tribunal decided to continue with the proceedings ex parte, trying to find answers to the requests made by the Philippines. In accordance with the PCA rules of arbitration, five arbitrators had to be appointed. In its opening letter, the Philippines suggested the first arbitrator. The PRC decided not to respond to the request to appoint an arbitrator, so the President of the PCA appointed the four other arbitrators.

At this point, the Chinese government sent a Note verbale to the PCA, stating that it “does not accept the arbitration initiated by the Philippines”, which it would repeat several times throughout the arbitral proceedings.[49] In accordance with Articles 3 and 9 of Annex VII of UNCLOS, however, the Tribunal can proceed if one of the parties is absent from the proceedings. The PCA, in this case, decided to continue with the proceedings. Much to the dismay of the Philippines, the court decided, however, that it would not specifically go into the question of sovereignty and maritime delimitation. This decision was consistent with the written request made by the government of Vietnam, which sought to prevent a ruling that overlapped with its own sovereignty claims.[50]

In March 2014, the Philippines delivered its memorial to the arbitral Tribunal, containing all relevant arguments for the case made by the Philippines, including the claim that the dispute settlement mechanism was compulsory. Although the PRC did not submit a counter-memorial, the arbitral Tribunal started its work on delivering an award. Before the arbitral Tribunal could go into the arguments of the case itself, it had to deal with preliminary issues, such as the question of its jurisdiction and the admissibility of the case. The Tribunal covered three topics: (1) the status of both nations as Parties to UNCLOS, (2) the legal consequences of the non-participation of China in the proceedings, and (3) whether or not these proceedings constituted an abuse of legal process. Since both had signed and ratified UNCLOS, the arbitral tribunal held that both the Philippines and China are bound by the relevant procedures for international maritime dispute settlement. The arbitral Tribunal further stated that since neither of the parties had given a preference for the means of judicial settlement as mentioned under Article 287(1), the parties were considered to have agreed with the other procedure for dispute settlements. Furthermore, the arbitral Tribunal reaffirms that in accordance with Article 9 of Annex VII, one party could still ask for the proceedings to continue if the other party failed to appear.[51] Therefore, China’s absence from the proceedings did not bar the arbitral Tribunal from continuing with them. Lastly, the arbitral Tribunal replied to China’s claims that the creation of the arbitral Tribunal in and of itself was an abuse of rights.[52] The Tribunal referred to the precedent set by the Barbados v Trinidad and Tobago case, where the tribunal decided that “the unilateral invocation of the arbitration procedure cannot by itself be regarded as an abuse of right” as allegedly committed within the meaning of Article 300 of UNCLOS.[53] As a result, in the SCS case, the Tribunal also considered the invocation of the proceedings in this case not to be an abuse of rights.

Article 288(1) of UNCLOS provides that the jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal during a conflict settlement only covers “conflict concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention”. The arbitral Tribunal therefore had to look whether the issue as such constituted a conflict as meant under Article 288(1). China claimed it did not constitute such a conflict, since the issue was one of sovereignty and not of interpretation, and because it involved maritime delimitation, meaning it was exempt given China’s declaration in 2006. The arbitral Tribunal, however, ordered that the issue in fact constituted a conflict between the two States, based on two counter-arguments. As requested by the Philippines, the arbitral Tribunal first decided that, although a dispute over sovereignty in the SCS existed, it did not mean that the Philippines’ submissions raised questions of sovereignty as well.[54] Secondly, the Tribunal made a clear distinction between matters of maritime delimitation and cases in which certain rights in the EEZ are allegedly violated. The Tribunal stated that “[w]hile a wide variety of issues are commonly considered in the course of delimiting a maritime boundary, it does not follow that a dispute over each of these issues is necessarily a dispute over boundary delimitation.”[55] As a result, the tribunal held that the issue was a conflict as under Article 288(1) and therefore that the case was admissible.

The arbitral Tribunal also looked at the steps necessary before judicial dispute settlement could be considered. The arbitral Tribunal looked at Articles 281 and 282 to verify that it was not prevented from using UNCLOS, since the States might have agreed upon different means of dispute resolution. Regarding these two articles of the treaty, China claimed that the several treaties between the two parties (such as the China-ASEAN agreement or TAC) should be considered as viable alternatives to binding dispute settlement under Part XV of the Convention. The Tribunal disagreed however, stating that “neither [agreement] provides a binding mechanism and neither excludes other procedures.”[56] Finally, the arbitral Tribunal looked at possible exceptions and limitations to its jurisdiction. In this regard, the arbitral tribunal stated that

Article 298 provides for further exceptions from compulsory settlement that a State may activate by declaration for disputes concerning (a) sea boundary delimitations, (b) historic bays and titles, (c) law enforcement activities, and (d) military activities. By declaration on 25 August 2006, China activated all of these exceptions.[57]

The Tribunal therefore based its jurisdiction to rule on the merits on the question of whether they had to do with one of these four categories. Ultimately, the Tribunal unanimously ruled in favour of the Philippines on the question of jurisdiction, with the reservation that it would consider its jurisdiction during the merits phase.[58]

A. The Philippines’ Arguments

The Philippines submitted its written memorial with 15 submissions, requesting the tribunal to rule:

(a) That the tribunal had jurisdiction over the claims and the case is admissible,

(b) That China’s maritime entitlements would not exceed UNCLOS parameters,

(c) That China’s historic rights and the nine-dash line are contrary to UNCLOS,

(d) As to the status of several maritime features in the SCS, denying PRC sovereign rights or territorial sovereignty over the surrounding waters,

(e) That China’s failure to prevent Chinese vessels from exploiting the resources in the Philippine EEZ was unlawful,

(f) That China’s refusal to allow Philippine citizens to enjoy these exploitation rights was unlawful,

(g) That China’s occupation of (and construction on) Mischief Reef was contrary to UNCLOS,

(h) That China causing serious risk of collision by unlawfully operating its law enforcement vessels in a dangerous manner near Scarborough Shoal,

(i) That China failed to fulfil its obligations relating to environmental protection in the SCS,

(j) That China shall respect the rights and freedoms of the Philippines, shall protect the marine environment in the SCS and shall exercise its own rights in the SCS with due regard for the rights of the Philippines under UNCLOS.[59]

Philippines had two issues with China’s ‘historic rights’ in the SCS: (1) the PRC never had historic rights over these waters to begin with and (2) any of China’s rights in the SCS that went beyond the rights provided by UNCLOS were nullified after China’s accession to the UNCLOS.[60] According to the Philippines, the historic rights as claimed by China differed from “historic title” are referred to in Article 298, since this case involved areas very far away from China’s coast. According to the Philippines, this matter was not an issue of maritime delimitation, because no maritime territories were being called into question, and the claims were thus beyond the PRC’s entitlements under UNCLOS.[61] The Philippines disagreed with the PRC that this issue fell outside the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal. The Philippines also claimed that these historic rights that the PRC was claiming never existed, since the first assertion of these rights was in the UN note in 2009, which was decades after the Philippines had claimed effective control of the SCS islands.[62] In addition, the Philippines also stated that these historic rights claimed by PRC were not compatible with the Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) or international law, in general. The nine-dash line was claimed to be in conflict with UNCLOS, since it extended to more than 200 nautical miles from the coastal baseline (contrary to Article 76) and unlawfully extended the right to harvest the living resources into another State’s EEZ (contrary to Article 62). The Philippines claimed that even though the PRC may have implemented this territorial claim into its national law, this assertion went against international legal principles.[63]

Regarding the second part of the merits that “any of China’s rights in the SCS that went beyond the rights provided by UNCLOS were nullified after China’s accession to the UNCLOS”, the Philippines argued that the maritime features at issue were low-tide elevations, not islands, and therefore did not have their own territorial waters, EEZ or continental shelves. In the alternative, Philippines argued that the maritime features were rocks instead of islands and thus only had a territorial sea and a contiguous zone (and no EEZ or continental shelf), in accordance with Article 121(3). According to the claimant, these features were indeed rocks instead of islands, since in accordance with Article 121(3) of the Convention, rocks need to be able to “sustain human habitation or economic life” to have an EEZ or continental shelf. To decide whether a maritime feature is to be considered an island, the arbitral tribunal must look at all elements that constitute an island: geographical make-up, size, its ability to sustain human habitation or independent economic life and “without infusion from outside.”[64] This point was of particular importance to the Philippines, since a decision in its favour would “reduce the incentive [for China] to flex muscles and demonstrate sovereignty over miniscule features that generate a maximum entitlement of 12 nautical miles.”[65]

Regarding Chinese conduct in the SCS, the Philippines listed the activities that they considered to be a breach of Filipino rights. First, it considered the activities mentioned above under submission categories E and F to be a breach of its sovereign rights, because Chinese warships had on multiple occasions prevented its citizens from enjoying both non-living and living resources. Secondly, Chinese inaction had meant a failure to prevent Chinese nationals from unlawfully taking Filipino living resources. The PRC had allowed Chinese fishery workers from illegally fishing at Mischief Reef (less than 200 nautical miles from the coast and thus within the Filipino EEZ) and had even shielded the workers from Filipino law enforcement. Similarly, the Philippines argued that it had been denied the exercise of its sovereignty over its territorial sea around the Scarborough Shoal by Chinese ships patrolling the area.[66]

The Philippines argued that the Chinese had not fulfilled their obligations under LOSC to protect the marine environment, as the PRC had allegedly terraformed substantial parts of the maritime features of the SCS to create artificial islands. In addition, the Philippines claimed that the conduct of Chinese vessels in international waters and the Filipino EEZ had not been in line with rule 2 of the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS), since China had “intentionally endangered another vessel through high speed blocking.”[67]

The Philippines stated that the PRC had engaged in acts that aggravated the conflict, meaning that China had breached its obligation to use peaceful means to solve the dispute, as required under Article 279 of UNCLOS. Specifically, the PRC aggravated the conflict in that it had “dangerously altered the status quo”[68] and prevented the normal workings of the Filipino armed forces within their EEZ.[69] Lastly, the Philippines chided the PRC for its past “significant, persistent and continuing violations” and demanded that in the future, China act with due regard for both the environment and the sovereign rights and State sovereignty of the Philippines. The claimant believed that this grievance should be explicitly expressed, because of past transgressions in relation to fishing and navigation.[70]

B. The Chinese Response to the Allegations

As explained before, the PRC viewed the tribunal as set up under this compulsory arbitration procedure as unnecessary and even an abuse of legal process. It was for this reason that unlike the Philippines, the PRC decided not to submit a written submission to the arbitral tribunal. Moreover, since it held the view that the arbitral tribunal had no jurisdiction over the matter, the PRC decided not to participate in any of the proceedings. The PRC sent a position paper to the arbitral Tribunal, in which it gave its arguments for not participating and why, in its view, the arbitral Tribunal had no jurisdiction in the case.[71] Although position papers are not, strictly speaking, official documents addressing the merits of any case, such papers can still be used to determine the main arguments of a party, like the four main arguments of the PRC in this case. The first argument was that an arbitral tribunal as set up under Section XV of UNCLOS had jurisdiction only in cases that concerned the interpretation or application of UNCLOS, in accordance with Article 279. The PRC pointed out that the requests made by the Philippines in essence boiled down to the question of territorial sovereignty, which falls outside the scope of the UNCLOS.[72] To make this point, China referred to the principle of ‘the land dominates the sea’ from the Qatar v Bahrain case, in which the ICJ held that maritime rights derive from the coastal State’s sovereignty over the land.[73] The PRC claimed, therefore, that to question the right to territorial waters and EEZ for the islands in the SCS would be to question China’s historic right to sovereignty over the land of the islands. The PRC stated,

Whatever logic is to be followed, only after the extent of China's territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea is determined can a decision be made on whether China's maritime claims in the South China Sea have exceeded the extent allowed under the Convention.[74]

Such a dispute would fall outside the scope of Article 279 and thus would not be subject to adjudication by a tribunal set up under Part XV of UNCLOS.

The PRC maintained that the question whether maritime features can be appropriated is a matter of State sovereignty and that it was therefore not a matter to be decided by the arbitral Tribunal (or governed by UNCLOS, for that matter). Furthermore, China stated that in order to fully address the maritime rights bestowed upon them, the so-called Nansha Islands should be considered as a whole and not as separate maritime entities. China claimed that by only addressing certain elements of several of the features, the Philippines was dissecting the group of islands in its favour and thereby trying to downplay the fact that China already had already established its sovereignty over other islands in the island chain, like Taiping Dao.[75] Further, China denied that it had ever prevented Filipino vessels from enjoying their right of navigation in Chinese waters, in accordance with the Convention.

The second main argument set forth by the PRC in their position paper was that there was an agreement between the Philippines and China to settle disputes through peaceful and friendly negotiations—an agreement which allegedly preceded the LOSC compulsory dispute-settlement procedure. In this agreement, it was stated that “disputes shall be settled by the countries directly concerned, without prejudice to the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.”[76] On this issue, the PRC found itself to be supported by Article 282 of UNCLOS, which states that parties to a dispute concerning the interpretation or application of UNCLOS can agree to settle the dispute through other means of binding dispute settlement, if agreed upon by the States party. The PRC maintained that certain words, like “agree” and “undertake”, created specific obligations for the parties to adhere to, while the words “eventually negotiating a settlement” signified a bar to other forms of dispute settlement. Precedent from the Southern Bluefin Tuna case arguably supported this claim, as the ICJ stated that wording does not need to be explicit for it to constitute such a bar.[77] The PRC noted in this regard that a mere exchange of views without aiming to solve the dispute is not considered proper negotiations, according to the ICJ in the Georgia v Russian Federation case.[78]

The third argument of the Chinese position paper was that the PRC’s 2006 declaration on Annex VII of the Convention precluded any dispute based on maritime delimitation. In this declaration, the PRC precluded all disputes regarding matters of maritime delimitation, as meant under Article 286 of UNCLOS. The PRC stated that the two States had on multiple occasions stated that this issue in the SCS was a matter of maritime delimitation, to be solved through diplomatic dispute settlement.[79] The PRC maintained that issues raised by the Philippines still pertained to maritime delimitation. In the eyes of the PRC, there was a pre-condition to arguing that PRC had interfered with the rights of Filipino vessels in a certain part of the SCS: clarification beforehand as to whether this part of the SCS was part of the Filipino EEZ or not. This clarification would entail engaging in the exercise of maritime delimitation, which (according to China) would not only have been outside the scope of ‘interpreting the Convention’, but also in conflict with China’s 2006 statement on Annex VII.

The last main argument from the position paper was that PRC’s decision not to participate in the proceedings was supported by international law. The Chinese position was that to participate in these proceedings and accept that their scope could be broadened to include sovereignty issues, and would be to deny “the integrity of Part XV of the Convention as well as the authority and solemnity of the international legal regime for the oceans.”[80] Finally, the PRC referred to Article 280 of UNCLOS to support its position of non-cooperation, since this provision allows States to agree upon a different method of dispute settlement, where the interpretation or implementation of UNCLOS is concerned.[81] This argument was of course in line with China’s second argument that the agreements between the two States precluded any form of compulsory means of dispute settlement.

C. The Arbitral Tribunal’s Award

On 12 July 2016, the arbitral Tribunal responded to all of the Philippines’ submissions and delivered its decision. The first issue for the arbitral Tribunal to address was the nine-dash line and the PRC’s claim of historic rights. The arbitral Tribunal disagreed with the PRC’s claims that Article 298 provided for valid exceptions. On the first count, the arbitral Tribunal held that a dispute on overlapping maritime entitlements is not about maritime delimitation just because ‘overlapping entitlements’ are necessary for delimitation. As requested, the arbitral Tribunal specifically did not rule on the validity of China’s historic rights, so it found China’s argument that the Tribunal had no jurisdiction to rule over matters of sovereignty to be irrelevant. The Tribunal also found that any historic rights that China might have had before it ratified UNCLOS to be superseded by UNCLOS would be incompatible with UNCLOS “to the extent that they exceed[ed] the geographic and substantive limits of China’s maritime entitlements under the Convention.”[82]

Regarding the second grouping of submissions, the arbitral Tribunal tried to answer two separate questions: (1) are the maritime features in the SCS low-tide features or high-tide features, and (2) are they rocks or islands? To answer the first question, the Tribunal looked at Article 13 of UNCLOS, and at expert opinions. The arbitral Tribunal found it proven that the Scarborough Shoal, Cuarteron Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Johnson Reef, McKennan Reef, and North Gaven Reef are all high-tide features, since all of these features are wholly or partly above water at high tide. They therefore provide a territorial sea and a contiguous zone, but no EEZ or continental shelf. Conversely, Hughes Reef, South Gaven Reef, Subi Reef, Mischief Reef and the Second Thomas Shoal are all low-tide features and thus do not provide the owner with territorial waters or a contiguous zone.[83]

On the question of rocks versus islands, the arbitral Tribunal looked at how to identify the concept of sustaining human habitation or economic life and how the answer to this question applies to the features in the SCS.[84] The arbitral Tribunal found that features such as the Scarborough Shoal have high-tide features, but no evidence was found that these features can assist the fisheries workers currently there in their economic activities, let alone allow for human habitation. These features are considered to be rocks instead of islands and therefore yield no EEZ or continental shelf. The arbitral Tribunal specifically noted that it was aware that there were construction activities on these features, but that these activities cannot be used to enhance the status of the features to islands, as the features were not naturally formed.[85]

The arbitral Tribunal also focused on Chinese activities in the SCS. The arbitral Tribunal found that the PRC does indeed infringe on the Philippines’ sovereign rights to enjoy non-living and living resources within its own EEZ (as found under Articles 77 and 56), by having warships patrol the Filipino EEZ and allowing Chinese fisheries workers to fish in the Filipino EEZ under the 2012 PRC moratorium. Furthermore, the arbitral Tribunal found that the PRC’s ships stopping Filipino fisheries workers from fishing at the Scarborough Shoal constituted unlawful actions under UNCLOS, since these were actions by warships in foreign waters, but also noted that this finding did not take into consideration the question of sovereignty.[86]

Based on expert reports, the arbitral Tribunal found that Chinese building and fishing activities harmed the marine environment, for example, by destroying reefs and coral beyond repair, thus constituting a breach of the PRC’s obligations to protect the environment under Part XII of UNCLOS. According to the arbitral Tribunal, the same construction activities also constituted breaches of Articles 60 and 80 of the UNCLOS, since they involved construction within the Filipino EEZ without Filipino consent.[87] After all, Article 60(1) of UNCLOS states that only the coastal State has a right to build artificial islands in its EEZ. Lastly, the arbitral Tribunal fully agreed with the Philippines and found that the PRC did indeed violate the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS) by intentionally performing dangerous manoeuvres nearby Filipino ships. The arbitral Tribunal found China was in violation of Article 94(4c) of the COLREGS, which states that flag States shall make sure that captains “observe the applicable international regulations concerning the safety at sea.”[88]

The arbitral Tribunal also agreed with the Philippines that the PRC did indeed aggravate the conflict by building artificial islands in the disputed waters. According to the arbitral Tribunal, the PRC had been forcing the Philippines’ hand by building artificial islands harming living resources and defacing marine features, in waters that might not even end up being Chinese after the settlement of the dispute. The arbitral Tribunal, however, expressed the belief that no further statement on the matter of the PRC’s future conduct needed to be made, since the obligation to abide by international law goes without saying. The Tribunal saw no reason to believe that this obligation might be inapplicable to this case and pointed to the Vienna Convention: “Every treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith.”[89]

IV. Assessment of the Award and Its Legal and Practical Implications

Because of the territorial nature of the dispute concerned and, partly, the fact that a (regional) superpower, China, was involved in the discussion, the case has been garnering attention from media and governments around the world. As the discussions surrounding the case would have it, the arbitration award itself and its aftermath have given us interesting answers to some important legal and practical questions with far-reaching consequences. The more practical questions that are raised by the award are: (1) what does the award mean for the maritime-delimitation lines and the nine-dash line in the South China Sea and (2) how does this award contribute to the resolution of the SCS dispute?

First, as we have seen, the PCA has sternly rejected the use of the nine-dash line as an official maritime delimitation and rejected the claim of historic rights. In doing so, the PCA clearly signalled that State parties are to use standard UNCLOS demarcations for the SCS. Since the arbitral Tribunal also ruled that the disputed maritime features only provide a 12 nautical territorial zone at most and no EEZ, the decision also means that large swathes of the SCS have returned to being legally res nullius—free terrain for all states involved. In theory, the fact that there are no longer any overlapping EEZs should drastically reduce the chances of a legally valid dispute in the future.

Another implicit practical consequence could be the PRC, in accordance with the ruling, being legally bound to forfeit most of its claims to the islands in the SCS. Not much has changed ‘on the ground’ since the ruling of 2016, however, as China continues to reject the jurisdiction of the PCA to rule in this matter. This point brings us to a second: how can the arbitral award contribute to the resolution of the dispute? Before the award, some authors had suggested that legal frameworks allow for different cooperation in exploiting the islands and the seabed in a cooperative fashion, even going so far as to start joint operations between the different States, provided they have the political will for it.[90] Given that the Chinese had opposed the arbitration from the start, it might be possible that the Philippines did not specifically seek a ruling to solve the dispute, but rather as a bargaining chip. ASEAN seems to have played an important role here. In the ASEAN meeting directly after the award was made, a statement was written in which no mention was made about the ruling, despite the issue having been a major point of contention in the region.[91] In light of this statement, a possible future for joint development agreements might not be off the table just yet.

Apart from this consideration, it is important to take note of China and Taiwan’s unexpected aligned interests on the matter. Since tensions between Taiwan and the PRC are at a long-time high, the fact that they agree that the SCS is Chinese territory is therefore heralded as an unexpected boon for cross-strait interactions.[92]

Different parties may see the merit of using voluntary maritime dispute settlement, because this mechanism would allow them to dictate the pace, form and result of the negotiations by themselves. It does not, however, mean that negotiations would be without obligations for the parties,[93] since it is established by precedent that States are considered to have an obligation to “exchange views” on how to solve an issue or implement an agreement.[94] ICJ has stated that parties

are under an obligation to enter into negotiations with a view to arriving at an agreement, and... are under an obligation so to conduct themselves that the negotiations are meaningful, which will not be the case when either of them insists upon its own position without contemplating any modification of it.[95]

This judgment seems to underline this requirement. The PCA seems to have agreed with the claimant that restricting the dispute-settlement effort to merely diplomatic channels was not helping resolve the conflict. In light of the circumstances of the case and the fact that reclamation and building efforts still continue on a daily basis, the author finds this to be an understandable decision by the Court.

Besides the practical implications, the ruling naturally also sought to answer legal questions.[96] To explore this aspect of the case, I would like to provide an overview of the most relevant legal points put forward by this case. The first point stems from the PRC’s determination not to participate in the proceedings and not to recognize the jurisdiction of the court. As the Tribunal explained, non-participation is not a requirement to proceed with the case, but it can mean that relevant legal questions remained unanswered.[97] This risk is of particular relevance in cases of maritime delimitation, which relies heavily on the cooperation of experts and technical evidence from both sides for the relevant award. Moreover, the PRC’s non-recognition of the arbitral Tribunal in this case means that the Philippines paid both its own and China’s share of the costs.[98] Therefore, like in most maritime cases, the legal questions were relatively complex, and as many experts were involved in the lengthy hearings, these costs were relatively high. To smaller states, these high expenses could be a serious barrier to access to adjudication.

A second point stems from the fact that China is not abiding by the award delivered. Non-compliance with rulings from international courts has precedent, in the Arctic Sunrise case and the Nicaragua v USA case, in which Russia and the USA respectively decided to disregard the outcome of the international dispute settlement.[99] However, if non-compliance is not met with enforceable sanctions, it could incentivize powerful states to ignore a ruling that is not in their favour. A tradition of non-compliance could thus be seriously detrimental to the reputation of international arbitration as a source of justice.

A third point lies in the fact that the arbitral Tribunal reaffirmed the role of UNCLOS in the unification of dispute-settlement mechanisms. While under many treaties, parties are required to first exhaust other methods of dispute settlement such as negotiations, UNCLOS provides a very comprehensive legal framework, with fewer prerequisites for engaging in methods of mandatory dispute settlement. The exhausting of diplomatic alternatives was central to the arguments of the PRC, since it claimed that bilateral and regional negotiation agreements from the area in question should precede any arbitration procedures as a general principle. However, the arbitral tribunal’s insistence that this principle does not automatically preclude adjudication under UNCLOS is supported by legal theory on so-called procedural fragmentation. Rayfuse argues that parallel treaties, as well as declarations made with the objective of avoiding jurisdiction (such as the PRC’s 2006 declaration to the U.N.) and so-called ‘self-contained regimes’, all lead to a fragmentation of justice. This result was exemplified by the Swordfish case, in which both WTO and UNCLOS dispute-settlement mechanisms were employed to deal with the same case.[100] Like in the Swordfish case, the SCS award in its own way reinforces the international community’s commitment to preventing procedural fragmentation, by reaffirming the prevalence of mandatory maritime dispute settlement on the international level.

A fourth relevant point stems from the decisions that the arbitral Tribunal made on the status of the maritime features. As I have explained, several features were deemed unable to support ‘human habitation’ or ‘economic life’, but as one might imagine these concepts are marred with legal fuzziness. International case-law on this topic has been scarce to say the least, so there has been no strong challenge to the phrasing of UNCLOS. One notable instance of application comes from the Jan Mayen case,[101] in which it was decided that the size of the land area must also be taken into account, even if it could not support human habitation.[102] Most of the islands in the SCS are not big enough, however, for this exception to be taken into account in any case. It is also important to note that the arbitral Tribunal does not mention the position of the features, which according to some authors is a relevant oversight.[103] An island near the equator might be more susceptible to becoming suitable for sustaining economic life or human habitation than a rock that is near the North Pole. It is worth noting that one of the judges on the Tribunal, Professor Soons, stated that “if the capacity of an island not sustaining human habitation or economic life at present can be admitted on the basis of past human habitation or economic life, logic would also require admission on the basis of future capacity.”[104] Other authors have rightfully suggested that in this regard, modern technology can certainly have a role to play in creating ‘economic life’ where previously there was none.[105] The fact that the PCA declined to recognize some of the relevant maritime features as islands did not mean that these features are completely unusable for maritime-delimitation purposes. UNCLOS accordingly allows States to draw straight baselines from low-tide elevations when “lighthouses or similar installations which are permanently above sea level have been built on them”, but only when these baselines have “received general international recognition.”[106] This provision at least in part explains the sudden surge in installations and lighthouses being built in the SCS by the PRC. Because the status of these elevations in those cases becomes dependent on international political recognition, the issue can once again become politicized, despite any earlier ruling by the PCA.

A fifth point relates to the arbitral Tribunal’s decision to see the islands as separate entities and not as one entity. The question whether or not a group of islands is considered an archipelago is relevant, since coastal states are allowed to draw straight baselines between the different islands within the archipelago. As we have seen in the case at hand, these rights are sometimes challenged, since it is not easy to prove that a group of islands is indeed an intrinsic geographical or political ‘entity’. The PRC sees all islands in the SCS as part of the Nansha Island group, interlinked in their respective rights for territorial waters and continental shelves. Conversely, the Philippines advocated separating the islands into different entities, since doing so would allow for a ruling on each of the specific maritime features and would prevent the PRC from treating as territorial waters the features that were closest to the Filipino shoreline, since this would dissuade China from “flexing its muscles” on islands near Filipino shores.[107] In its award, the arbitral Tribunal notably decided to leave out Nanhai Zhudao, the Pratas Islands and Itu Aba, which have a higher probability of being recognized as islands owing to a tradition of human habitation.[108] Therefore, there could still be a debate on whether these islands are part of an archipelago or should be considered separate entities. In future cases, the Chinese could reopen the debate on the status of these features by arguing that the tribunal, without reasonable explanation, ignored the fact that Article 47 of UNCLOS defines an archipelago as a single geographical, political and economic entity.

A sixth point to be noted is that the arbitral Tribunal reaffirmed that States have a weighty obligation to protect the environment, not just within their own territory, but also in disputed areas or common areas. This ruling thus set an important precedent for States to follow: due consideration has to be given when building artificial islands (if it is allowed at all). Scholars have already noted that it is of great importance for the broader field of environmental law that the Tribunal decided to dedicate a lot of energy to disseminating that argument carefully.[109] As coral and marine biodiversity both fall under what environmental lawyers consider the global commons,[110] it is commendable that the arbitral tribunal decided to underline the State’s responsibilities when it comes to sustainable development and protection of the environment.

A seventh point is related to the nature of the dispute, as China insists the dispute was at its core a maritime-delimitation issue. China also maintains that any ruling on the SCS would involve the PCA making a decision on sovereignty rights in the SCS, for which even the Tribunal itself said it has no jurisdiction. Whether or not China was breaching a right or obligation in certain areas was therefore dependent on the question of whether or not the maritime features belonged to China in the first place. The PRC stated,

To decide upon any of the Philippines’ claims, the Arbitral Tribunal would inevitably have to determine, directly or indirectly, the sovereignty over both the maritime features in question and other maritime features in the South China Sea. Besides, such a decision would unavoidably produce, in practical terms, the effect of a maritime delimitation… Therefore, China maintains that the Arbitral Tribunal manifestly has no jurisdiction over the present case.[111]

This argument also explains why some authors would hold that the two elements are too interconnected and that the principle of domination of land over sea should effectively prevent such a ruling. One author says that “where a territorial dispute is part of the subject-matter of a maritime dispute relating to delimitation, the former must be resolved before the latter can be considered.”[112] It is therefore only fitting that arbitral tribunal specifically made a distinction between maritime-delimitation cases and regular cases of maritime law: “a dispute over the source and existence of maritime entitlements does not ‘concern’ sea boundary delimitation merely because the existence of overlapping entitlements is a necessary condition for delimitation.”[113] This distinction is relevant because the ruling will stand or fall with it. It can, however, be argued that with this definition, the arbitral Tribunal circumvented the question of what delimitation is and left it open for discussion in future cases. It is therefore possible that if the arbitral Tribunal had ruled that it is indeed a matter of delimitation, then a ruling on the status of the nine-dash line and China’s ‘historic rights’ would have changed the course of the proceedings entirely. In addition, the PCA can only rule on cases in which the parties have agreed to settle disputes that arise from a “defined legal relationship, whether contractual, treaty-based, or otherwise.”[114] It is therefore important that the PCA reinforced this notion by making its ruling, since both parties willingly and knowingly signed the convention, including its rules for settlement procedures.

The final point in the case that I wish to mention here concerns the finality of the award. UNCLOS defines the finality of an award as the absence of any possibility to appeal the judgment, but it does not prohibit States from starting adjudication by other courts and tribunals.[115] In theory, therefore, one of the parties could have the SCS case reopened by another tribunal. However, other tribunals or courts are unlikely to reopen the case without new developments, because of the widely accepted legal principle of res judicata. This principle states that a case should not be reopened if the parties, the claims and the grounds remain sufficiently similar.[116]

V. Final Thoughts on the South China Sea Case

This paper has explored both the practical and legal implications of the SCS arbitration. In doing so, it has demonstrated the importance of the case for both the field of the international law of the sea and international dispute settlement. As shown in this paper, however, territorial disputes over the SCS still linger even though the proceedings ended in 2016. For example, the Chinese government has repeatedly stated that it does not recognize the PCA’s jurisdiction to rule on these matters, as it sees the issues surrounding the SCS as typically related to matters of sovereignty.

For the moment, it is still hard to predict whether diplomatic avenues might prove more fruitful in solving the SCS dispute. Given the issues with the enforceability of the award, it might still be the most viable path towards solving the disagreements over entitlements in the SCS. In this regard, the tribunal noted that “that the root of the disputes at issue in this arbitration lies… in fundamentally different understandings of [the parties’] respective rights under the Convention in the waters of the South China Sea.”[117]

In a more general legal sense, the fact that China decided to not abide by the ruling can be considered troublesome for the reputation of international dispute settlement. If non-compliance with international rulings occurs more often in similar cases, it could mean that some States will no longer see mandatory dispute-settlement mechanisms as a way to settle international disputes.

In light of these issues with non-compliance, with the enforceability of the award and with the continued military build-up in the SCS, a lasting solution may require a shift not only in jurisdiction, but also in the political mentality of the governments involved.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Thanh-Dam Truong & Karim Knio, The South China Sea and Asian Regionalism: A Critical Realist Perspective (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016) at 3 [Truong & Knio].

-

[2]

Steve Rolf & John Agnew, “Sovereignty Regimes in the South China Sea: Assessing Contemporary Sino-US Relations” (2016) 57:2 Eurasian Geography and Economics 249 at 254.

-

[3]

Yoshifumi Tanaka, The International Law of the Sea (Cambridge: Cambridge Printing Press, 2015) at 22 [Tanaka].

-

[4]

Ivan Shearer, “The Limits of Maritime Jurisdiction” in Clive Schofield, Seokwoo Lee & Moon-Sang Kwon, eds, The Limits of Maritime Jurisdiction (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2014) 52 at 52 [Shearer].

-

[5]

Tanaka, supra note 3 at 30.

-

[6]

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 3, art 309 (entered into force 16 November 1994) [UNCLOS].

-

[7]

Ibid, art 5.

-

[8]

Ibid, arts 2-5, 17-19, 28, 46-47.

-

[9]

Shearer, supra note 4 at 51; UNCLOS, supra note 6, art 33.

-

[10]

UNCLOS, supra note 6, art 56(1)(a).

-

[11]

Ibid, arts 55, 56(1)(a).

-

[12]

Ibid, Annex II.

-

[13]

Ibid, arts 76(1), 76(8), 77(1), Annex II, art 3(1)(a); Shearer, supra note 4 at 58-59.

-

[14]

Ibid, art 86.

-

[15]

Ibid, art 87.

-

[16]

Ibid, art 54.

-

[17]

Ibid, arts 86, 87, 136.

-

[18]

Ibid, art 121(1).

-

[19]

Ibid, art 121(2).

-

[20]

Ibid, art 60(8).

-

[21]

Ibid, art 121(3).

-

[22]

Ibid, art 121(3).

-

[23]

Ibid, art 13.

-

[24]

Ibid, art 287; see also Nong Hong, UNCLOS and Ocean Dispute Settlement. Law and Politics in the South China Sea (London: Routledge, 2012) at 43-44 [Hong].

-

[25]

Truong & Knio, supra note 1 at 48.

-

[26]

Treaty of Peace between Japan and the Republic of China, Japan and China, 28 April 1952, 138 UNTS 3, art 2 (entered into force 5 August 1952).

-

[27]

Su Wei, “Some Reflections on the One-China Principle” (1999) 23 Fordham Intl LJ 1169 at 1170.

-

[28]

Hendrik W Ohnesorge, “A Sea of Troubles: International Law and the Spitsbergen Plus Approach to Conflict Management in the South China Sea” in Enrico Fels & Truong-Minh Vu, eds, Power Politics in Asia’s Contested Waters Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea (Cham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 2016) 25 at 27-28.

-

[29]

Philippines v China [2013] ICGJ 495, Philippines Memorial, paras 1.32, 2.2, 3.2, 3.3, 6.108, 6.114, 7.35 [Philippines].

-

[30]

Ibid, Final Award at para 174; the name “Nansha” is used by the PRC to denote both the Spratly Islands and surrounding island chains.

-

[31]

UNDOALOS, “Chronological Lists of Ratifications of, Accessions and Successions to the Convention and the Related Agreements”, online: United Nations <http://www.un.org/Depts/los/reference_files/chronological_lists_of_ratifications.htm>.

-

[32]

UNDOALOS, “Declarations and Statements: China”, online: <http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm#China%20after%20ratification>.

-

[33]

UNCLOS, supra note 6, art 310.

-

[34]

Robert D Kaplan, Asia’s Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific (New York: Random House, 2014) at 103.

-

[35]

PRC, Note Verbale, Doc CML/17/2009, New York, 7 May 2009, online: United Nations <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/chn_2009re_mys_vnm_e.p>.

-

[36]

Philippines, supra note 29, Philippines Memorial at paras 4.5, 4.6.

-

[37]

Zou Keyuan, Law of the Sea in East Asia: Issues and Prospects (New York: Routledge, 2005) at 48; Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at para 181.

-

[38]

PRC, Note Verbale, Doc CML/8/2011, New York, 14 April 2011, online: United Nations <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/mysvnm33_09/chn_2011_re_phl_e.pdf>.

-

[39]

Taiwan, Position Paper on ROC South China Sea Policy, 21 March 2016 at 1, online: MOFA <http://multilingual.mofa.gov.tw/web/web_UTF-8/South/Position%20Paper%20on%20ROC%20South%20China%20Sea%20Policy.pdf>.

-

[40]

Clive Schofield, “What’s at Stake in the South China Sea? Geographical and Geopolitical Considerations” in Robert Beckman et al, eds, Beyond Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea: Legal Framework for the Joint Development of Hydrocarbon Resources (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013) 11 at 20-21 [Beckman].

-

[41]

David Jay Green, The Third Option for the South China Sea: The Political Economy of Regional Conflict and Cooperation (New York: Palgrave Macmillan Publishing, 2016) at 4 [Green].

-

[42]

Tim Stephens, “The Collateral Damage from China’s ‘Great Wall of Sand’: The Environmental Dimensions of the South China Sea Case” (2017) 34:1 Austl YB Intl L 41 at 42.

-

[43]

ASEAN, Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, Indonesia, 24 February 1976 [TAC] (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore & Thailand); Truong & Knio, supra note 1 at 2.

-

[44]

Hong, supra note 24 at 14.

-

[45]

Philippines, supra note 29, Philippines Memorial at para 1.29.

-

[46]

Ibid at paras 1.30, 1.31, 1.33.

-

[47]

Philippines, supra note 29, Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility at para 26.

-

[48]

Ibid, para 27.

-

[49]

Ibid at paras 37, 56, 64.

-

[50]

Ibid at para 54.

-

[51]

Ibid at paras 106, 109, 113.

-

[52]

PRC, “Position Paper of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Matter of Jurisdiction in the South China Sea Arbitration Initiated by the Republic of the Philippines” at para 3, online: FMPRC <http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1217147.shtml> [PRC paper].

-

[53]

Philippines, supra note 29, Jurisdiction Award at para 126.

-

[54]

Ibid at para 152.

-

[55]

Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at para 155.

-

[56]

Ibid at para 159.

-

[57]

Ibid at para 161.

-

[58]

Ibid, Jurisdiction Award at para 413.

-

[59]

Ibid, Philippines Memorial at 271-272.

-

[60]

Ibid, Final Award at para 188.

-

[61]

Ibid, Philippines Memorial at paras 7.139, 4.20.

-

[62]

Ibid, Final Award at para 199.

-

[63]

Ibid, Philippines Memorial at paras 4.39, 4.50, 4.75, 4.86.

-

[64]

Ibid, Final Award at paras 291, 410-416.

-

[65]

Ibid at para 421.

-

[66]

Ibid at paras 686, 724, 772.

-

[67]

Ibid at paras 1059, 1069.

-

[68]

Ibid at para XXX.

-

[69]

Ibid at para 1139.

-

[70]

Ibid at para 1186.

-

[71]

PRC Paper, supra note 52 at paras 1-2.

-

[72]

Ibid at para 8.

-

[73]

See Qatar v Bahrain [1994], ICJ Rep 112, ICGJ 81 at para 185.

-

[74]

PRC Paper, supra note 52 at paras 10-11.

-

[75]

Ibid at para 22.

-

[76]

Ibid at para 31.

-

[77]

See New Zealand v Japan [2000], ICGJ 337, 38 ILM 1624, Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility.

-

[78]

PRC Paper, supra note 52 at para 46.

-

[79]

Ibid at paras 59-64.

-

[80]

Ibid at para 85.

-

[81]

Ibid at paras 77, 80.

-

[82]

Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at paras 204, 262.

-

[83]

Ibid at paras 303, 482; UNCLOS, supra note 6, art 13(1).

-

[84]

UNCLOS, supra note 6, art 121(3).

-

[85]

Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at paras 559, 562, 565.

-

[86]

Ibid at paras 716, 757, 814.

-

[87]

Ibid at para 415.

-

[88]

Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 20 October 1972, 1050 UNTS 16 (entered into force 15 July 1977).

-

[89]

Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at paras 1195, 1201.

-

[90]

Peter Cameron & Richard Nowinski, “Joint Development Agreements: Legal Structures and Key Issues” in Beckman, supra note 40 at 152.

-

[91]

Ian Storey, “Assessing the ASEAN-China Framework for the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea” (2017) 62 Perspective 1.

-

[92]

Hong, supra note 24 at 210.

-

[93]

Charter of the United Nations, 26 June 1945, Can TS 1945, No 7 at arts 2(3), 2(4).

-

[94]

Tanaka, supra note 3 at 417; Natalie Klein, Dispute Settlement in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) at 24.

-

[95]

Germany v Denmark [1969] ICJ Rep 3, ICGJ 150, Merits, Judgment at 47.

-

[96]

Green, supra note 41 at 4.

-

[97]

Philippines, supra note 29 at paras 122-124.

-

[98]

Ibid at para 110.

-

[99]

Ibid at para 121.

-

[100]

Rosemart Rayfuse, “The Future of Compulsory Dispute Settlement under the Law of the Sea Convention” (2005) 36 VUWLR 683 at 700, 704.

-

[101]

Denmark v Norway [1993] ICJ Rep 38, ICGJ 94, Reply Submitted by the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark, vol I at para 328.

-

[102]

Alex G Oude Elferink, “Clarifying Article 121(3) of the Law of the Sea Convention: The Limits Set by the Nature of International Legal Processes” (1998) IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin (Summer 1998) at 61.

-

[103]

Warrick Gullett, “The South China Sea Arbitration’s Contribution to the Concept of Juridical Islands” (2018) 47 Questions of Intl L (Zoom In) at 5.

-

[104]

Barbara Kwiatkowska & Alfred H A Soons, “Entitlement to Maritime Areas of Rocks Which Cannot Sustain Human Habitation or Economic Life of Their Own” (1990) 21 Nethl YB Intl L 139 at 153.

-

[105]

Irini Papanicolopulu, “The Land Dominates the Sea (Dominates the Land Dominates the Sea)” (2018) 47 Questions of Intl L (Zoom In) at 39.

-

[106]

UNCLOS, supra note 6, arts 7(4), 47(4).

-

[107]

Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at para 421.

-

[108]

Hong, supra note 24 at 209.

-

[109]

Carina Costa de Oliveira & Sandrine Maljean-Dubois, “The Contribution that the Concept of Global Public Goods Can Make to the Conservation of Marine Resources” in Carina Costa de Oliveira et al, eds, Protecting Forest and Marine Biodiversity. The Role of Law (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017) 290 at 307, 310.

-

[110]

Timo Koivurova, Introduction to International Environmental Law (Milton Park: Routledge, 2014) at 100.

-

[111]

PRC Paper, supra note 52, at para 29.

-

[112]

Jia Bing Bing, “The Principle of the Domination of the Land over the Sea: A Historical Perspective on the Adaptability of the Law of the Sea to New Challenges” (2014) 57 German Yearbook of International Law at 22.

-

[113]

Philippines, supra note 29, Final Award at para 204.

-

[114]

Permanent Court of Arbitration, Arbitration Rules 2012, art 1(1), online: PCA <https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/11/PCA-Arbitration-Rules-2012.pdf>.

-

[115]

UNCLOS, supra note 6, art 296, Annex VI, art 33, Annex VII, art 11.

-

[116]

Stefan Talmon, “The South China Arbitration and the Finality of ‘Final’ Awards” (2017) 8:2 Journal of International Dispute Settlement 1 at 3, 10.

-

[117]

Philippines, supra note 29, Press Release no 11.

List of figures

Image 1

List of tables

Table 1

The Different Maritime Zones (UNCLOS)