Abstracts

Abstract

This teaching practice report concerns a doctoral workshop developed by the authors in order to prepare Ph.D. students to participate in “Dance Your Ph.D.” – an international contest of online videos, whereby doctoral students use dance to communicate their research. This workshop provides Ph.D. students with the theoretical and methodological basis, as well as choreographic tools, and the self-confidence necessary to take part in the contest. The first edition was organized fully online due to the COVID-19 lockdown. This initial constraint led to the development of a series of techniques that enabled holding a dance workshop remotely, using the Teams software. In this report, we describe how we adapted to organize the workshop online and how this led to pedagogical innovations that we continued to use in subsequent hybrid iterations of the workshop. Discussing the possibilities and challenges presented by our pedagogical approach, we position this text within related literature debates and identify directions for future research for both embodied and virtual pedagogies.

Keywords:

- Dance,

- choreography,

- scientific communication,

- hybrid teaching,

- online teaching,

- art and science

Résumé

Ce rapport de pratique pédagogique concerne un atelier doctoral que nous avons développé afin de préparer des doctorantes et doctorants à participer au concours « Dance Your Ph.D. », un concours international de vidéos en ligne créées par des doctorantes et des doctorantes qui utilisent la danse pour communiquer leurs recherches. L’atelier leur apporte les bases théoriques et méthodologiques, les outils chorégraphiques ainsi que la confiance en soi nécessaires pour participer au concours. La première édition a été organisée entièrement en ligne en raison du confinement lié à la pandémie de la COVID-19. Cela a conduit au développement d’une série de techniques qui ont permis de tenir un atelier de danse en distanciel, via le logiciel Teams. Dans ce rapport, nous décrivons la manière dont nous nous sommes adaptés pour organiser cet atelier en ligne et comment cela a conduit à des innovations pédagogiques que nous avons maintenues dans les itérations suivantes de l’atelier avec un format hybride. En discutant des potentialités et des défis de notre approche pédagogique, nous positionnons notre texte au regard de la littérature scientifique et identifions des pistes de recherche futures pour continuer à développer des pédagogies à la fois incorporées et virtuelles.

Mots-clés :

- Danse,

- chorégraphie,

- communication scientifique,

- enseignement hybride,

- enseignement en ligne,

- art et science

Article body

Introduction

“Dance Your Ph.D.” is an international contest sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and Science Magazine. For this contest, Ph.D. students create online videos, using dance to communicate their research. The competition was created by John Bohannon in 2008 as a way of promoting more creative ways of communicating science through the performing arts (Leavy, 2020; Spry, 2016), specifically challenging scientists to pursue their research with/through movement and choreography (Bohannon, 2014) and to communicate their findings through this embodied format once recorded in a video. Doing so, the contest offers space for rethinking research as an embodied practice, seeking to reconcile long-held binaries between mind and body in knowledge creation (Mandalaki, 2019; Mandalaki & Pérezts, 2022).

To participate, Ph.D. students express their findings through solo or collective dance performances and share the YouTube or TikTok URL of their dance video (Science, 2023a). Entries are classified into one of four categories based on the scientific field of the thesis: Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and Social Sciences. The contest is organized in two phases. In the first phase, a panel of judges selected by AAAS choose a maximum of five dances in each field, based on both artistic and scientific merit. From this shortlist, a second panel of judges selects one winner in each of the four categories based on scientific merit, artistic merit, and creative combination of science and art (Leavy, 2020). The Category Winner receiving the highest total score awarded by the panel of judges wins the Grand Prize for that year’s “Dance Your Ph.D.” contest (Science, 2023b).

The contest itself is an interesting case study of how information technologies might be used in university teaching (Li, 2023). Indeed, even though the contest was launched twelve years before the first COVID lockdown, from the start it was done remotely through dance videos posted online. This format makes the contest accessible to participants worldwide (assuming a stable internet connection, which we recognize is not the case for everyone), as it can be organized at a reasonable cost. It also allows for wide exposure of the winning dance videos, and those of the other participants, through social networks and online articles featuring the videos, enabling Ph.D. researchers to disseminate their research to different audiences.

Dance Your Ph.D. Doctoral Workshop

The doctoral workshop presented here was developed by the authors at UCLouvain (Belgium) in 2020, 2022 and 2024 with the objective of providing UCLouvain Ph.D. students with the theoretical and methodological basis, as well as choreographic tools, and the self-confidence necessary to take part in the “Dance your Ph.D.” contest. The first edition of the workshop was organized completely online due to the COVID lockdown. Adapting to this initial constraint led to the development of a series of techniques that made it possible to hold a dance workshop remotely, in this case using Teams software. Some of these adaptations proved so successful that for the 2022 (and the planned 2024) version of the workshop we decided to use a hybrid format, structured around a mix of online and face-to-face sessions.

The first workshop was planned for four consecutive mornings in May 2020 and, for funding reasons, was restricted to humanities and social sciences faculty. Fifteen Ph.D. students from UCLouvain signed up. Each morning was supposed to start with one hour of theory in a classroom followed by two hours of workshop in a dance studio. In the first part of the week, the professors were going to give theoretical lectures presenting the contest, the objectives of the workshop and some of their own work combining art and science (Garoia et al., 2014, p. 14; Hernández Castro, n.d., 2022; Un desierto para la danza, 2015, p. 23, section I Love Buchomp). Through carefully crafted embodied exercises and discussions, the students would then move from oral to choreographic forms of sharing their research. For instance, students were asked to experiment with different qualities of movements (fast-slow, low-high), which gradually became more abstract (solid-liquid, active-passive) before finally trying to express totally abstract concepts with their movements (focus-distraction; democracy-totalitarianism). Towards the end of the week, the professors were going to adopt more of a coaching role, providing mentoring and feedback to the students as they worked on choreographing their individual dance videos. The goal of this workshop was not for the Ph.D. students to come out with a finished dance video. It rather sought to provide the students with useful tools while encouraging and supervising the first steps of their creative process. The aim was to nurture the participants’ ability and confidence, enabling them to develop a “Dance your Ph.D.” video in the following weeks and enter it in the contest the next January.

Although the 2020 lockdown (which started in mid-March in Belgium) began to ease at the end of April, it still prohibited us, the organizers, from holding an in-person dance workshop and made it impossible for Prof. R. Gomez Zuñiga to travel from Northern Mexico to Belgium. We postponed the workshop from May to late June, and then again to mid-December. By December 2020, Belgium was again under strict lockdown, so we decided to organize the workshop completely online. Due to the various changes and the shift to an online format, there were a few cancellations. In the end, we had six confirmed participants, all of them students from the UCLouvain faculties of history, humanities and business.

Online Dance Workshop

The program (see Table 1) was more-or-less the same as that for the workshop originally planned for May. However, having a fifth day allowed us to add the presentation of online choreography projects developed during the first lockdown (Gomez Zuñiga, 2021; Hernández Castro, 2021), and to make more time for individual coaching and feedback sessions with the participants. The remote dance workshop also offered space to explore the creative potential of pandemic-related restrictions that recent accounts in organization studies have discussed (e.g., Mandalaki & Daou, 2021; Pérezts, 2021). Of course, the online format also had a number of disadvantages, such as the lack of physical and sensorial engagement between participants and the physical surroundings or informal encounters for finding common ground to build trust and mutual involvement in the creative process. However, there were also positive aspects which we sought to leverage. First, the online workshop proved to be in line with the objectives of the “Dance your Ph.D.” contest, which from day one has taken place via dance videos rather than live performances. Navigating the pandemic restrictions forced us into a completely online format (Parrish, 2008; Plasson, 2018), although the initial project had been based on a more traditional approach (i.e., work involving physical interaction) with the unspoken assumption that the choreography would be prepared for the stage before being turned into a dance video. This challenged us creatively and had practical implications in terms of how we taught the online and subsequent hybrid workshops, as discussed next.

Table 1

Program for December 2020 Online Workshop

(a) Garoia et al., 2014, p. 14; Hernández Castro (n.d.). (b) Un desierto para la danza, 2015, p. 23. (c) Hernández Castro (2022). (d) Hernández Castro (2021). (e) Lozano (2021).

Two-Dimensional Dancing

Given the online format, we used language and techniques inspired by cinematography rather than stage performance. Specifically, instead of talking about stage left and stage right or upstage and downstage, as is common in physical stage performances, we talked about the bottom, top, right and left sides of the physical screen. On the first day, in addition to the exercises presenting the three dancing levels (low/floor, medium and high), we introduced and experimented with different shot sizes (extreme close-up, close-up, medium shot, long shot) and camera angles (eye level, low angle, high angle, overhead, ground level), as well as with the possibilities available with mobile cameras (e.g., point of view, sequence shot). Colleagues such as Li (2023) and McPherson (2018) have discussed the potential of digital means as innovative pedagogical practices for the creation of dance videos during the global pandemic. These studies specifically explain how recording embodied movement from different angles, in confined spaces, can be a form of dancing with the camera, and also point out some of the limitations of this approach (Li, 2023).

Much like in the aforementioned studies, in our case the camera was immediately included in the choreographic approach, allowing for embodied connections and involvement in the research process despite the lack of physical presence (Mandalaki & Daou, 2021). In the following days, we built on this approach by encouraging students to experiment with additional possibilities of the online digital format, such as different lighting (e.g., natural vs. artificial, backlighting; See Figure 1) and camera filters.

Figure 1

Online Backlight Dancing Exercise

Previous dance videos in the contest have been recorded in lab or fieldwork contexts (Bohannon, 2014). In our case, given the lockdown measures, participants were limited to the confines of their private spaces. As such, each participant joined the workshop from home (rather than meeting in the classroom and dance studio we had booked in May), rearranging their personal space as needed to accommodate dancing, in accordance with the contest’s instructions. On the second day, we presented an example and then participants experimented with the choreographic potential of various parts of their homes, figuring out how even confined and often small spaces (e.g., kitchen, bathroom, bedroom) might offer alternative movement possibilities not afforded in a dance studio or an office (Li, 2020; Spry, 2016). We further experimented with how dancers can use props, including work-related objects, to enhance their choreography. Notwithstanding the limitations of a purely online format – such as the absence of touch, being aware of others’ breathing or physical presence, or the atmosphere of the place (Kaasila-Pakanen et al., 2020), these exercises allowed us to turn some of the constraints of the lockdown into opportunities for creativity (Mandalaki et al., 2022; Pérezts, 2021).

Choreographing using Teams

The format of the workshop led us to explore how Microsoft Teams, the software used by UCLouvain, could be made into a pedagogical tool for a dance workshop (Godoi et al., 2021). On the second day, we organized a “Choreographing using Teams” exercise, whereby each participant took a turn as choreographer for the eight other dancers (Ph.D. students and workshop professors). Using chat or audio, the choreographer gave instructions to the dancers using the concepts learned during the first day (i.e., dancing levels, shot sizes, camera angles, screen borders). With these instructions to individual dancers and to the whole group, the choreographer created live simultaneous performances on the Teams mosaic display. Later in the week, during the individual choreography coaching, we started experimenting with the possibility of using a personalized background on Teams. This allowed the choreographer to assign the different dancers backgrounds that were meaningful to their process. The dancers then experienced how the background reacted when they started dancing.

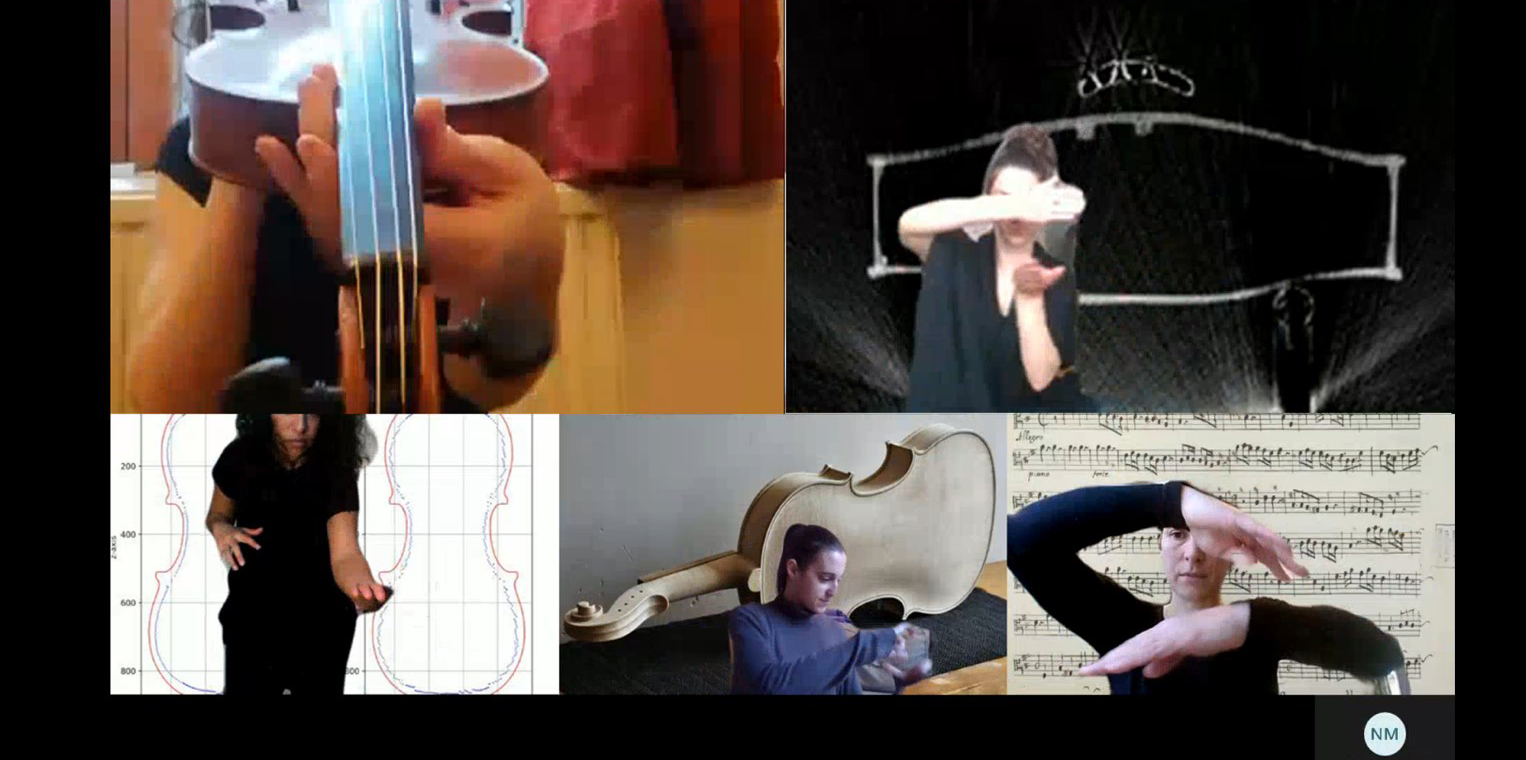

Another difficulty that arose with the digital interface was that the Teams software is designed to detect talking heads: a head and shoulders without a lot of movement. When dealing with other shot sizes (e.g., extreme close-up or long shot) of a person in motion, the software often struggles to distinguish the person from the background, such that the dancer often blends in with the background image (see Figure 2). Although this feature can seem confusing or uncomfortable, it also creates novel and creative ways of interacting with the images used to communicate the researcher’s process. In our case, this offered a multidimensional relationship to pictures and frames that differed substantially and creatively from the overused, monodirectional “person standing next to PowerPoint slides” presentation style of research outputs (Mandalaki et al., 2022). It also provided an almost “natural” example of an entanglement of dancing bodies and digital video technology, blending with its physical surroundings to co-create the final output in a post-humanistic way. Finally, the ease of recording Teams calls made it possible to record the Ph.D. students’ dances and use them as inspirational material for the students’ methodological research processes. At the end of the session, each participant was able to retrieve the video in order to use it as work-in-progress for review (Li, 2020).

Blended Dance Workshop

While the innovations in question were implemented out of necessity in the context of a forced digital format which led us to sustainably reconfigure how we approached our pedagogical and teaching practices (Kervyn et al., 2022), moving forward we recognized that they had significant potential. Conceptualizing this new way of teaching dance, the first author coined the term ‘VideoConfeDance’ (Hernández Castro, 2021), which also inspired the next editions of the “Dance your Ph.D.” workshop in UCLouvain. To keep the positive aspects of the online dance teaching and mitigate its limitations, in September 2022 the second “Dance your Ph.D. @ UCLouvain” workshop was organized using a blended/hybrid teaching method (See Table 2).

Figure 2

Dancing Experimentation Using Teams Background

As shown in Table 2, in 2022 we began with one morning session online followed by two in-person meetings. When physically present, in addition to choreographic and body exercises, we also left the dance studio to explore the choreographic potential of other places (hallways, classrooms, etc.). The fourth half-day was held online, taking advantage of the format to organize dance theories and exercises relevant to the online format. This involved presenting and experimenting with cinematographic language (framing, camera angles) and the possibilities of mobile cameras (selfie, point of view, sequence shot), interacting with the background image and using cinematographic language in choreography. Based on the students’ feedback from the first workshop, we also took time to present various tools and examples of how ideas and models might be turned into choreographies. For instance, we discussed how to use storyboards as an intermediary step, and we introduced some online tools for creating storyboards (storyboardthat.com; readfold.com).

Discussion

Despite the numerous lockdown-related obstacles faced when organizing this workshop, we approached these obstacles as opportunities for creativity (Mandalaki et al., 2022; Pérezts, 2021). Post-COVID, this has led us to keep some parts of the workshop online, leveraging the advantages of this format, while also seeking to navigate its limitations. The transition from a completely online workshop to a hybrid one, and the further adaptations we are planning to integrate for future workshops, were guided by the qualitative feedback we received from participants at the end of each workshop. Students’ overall feedback was positive, with suggestions for desirable adaptations (UCLouvain, 2022). We next discuss how we believe this workshop supported Ph.D. students in their research processes and enhanced their self-confidence. What we learned adds to related literature discussions about the possibilities and limitations of innovative pedagogical tools during and after the pandemic (Hernández Castro, 2021; Li, 2023; McPherson, 2018).

Table 2

Program for September 2022 Blended Workshop

Theoretical and Methodological basis

Ph.D. participants’ feedback stated that the workshop gave them the space to take a step back and reflect on their own theoretical and methodological positions from new perspectives. Engaging with the performative aspects of body movement, dance and other forms of art in how we research, write and teach, embraces vulnerable moments of being in relation to others (Spry, 2016), carrying the potential to meaningfully transform university and business school pedagogies (Jääskeläinen, 2023; Jääskeläinen et al. 2023; Mandalaki et al., 2022). Embodied practice, even when facilitated by technology, makes the researcher more aware of the vulnerability of the body (Mandalaki & Daou, 2021). In our case, experimenting with dance and artistic experimentation provided students with reflexive methodological tools for rethinking the conduct and writing of academic research as embodied, vulnerable practices with attention to the affective, relational body and the senses (Jääskeläinen, 2023; Mandalaki & Pérezts, 2022; Pérezts, 2021, 2022; Spry, 2016). In doing so, it allowed the bodies of the researcher and the researched to be reframed as sites of knowledge from where reflexive research with social and organizational significance can emerge (Mandalaki, 2023; Mandalaki & Pérezts, 2022).

Secondly, the first two workshops were restricted to Ph.D. students from the university’s humanities and social sciences faculty, limiting the breadth of exchange across epistemic disciplines. The upcoming workshop in 2024 will be open to all of the university’s faculties and academic levels (Ph.D. students, post-docs and professors). The outcome of the workshop will no longer be solely focused on the official “Dance Your Ph.D.” contest but on different ways in which choreography might be used in/for scientific research, writing, communication, and the dissemination of academic work. Broadening the type of participants and outcomes will hopefully allow for a wider appeal as well as rich multi-disciplinary exchanges between diverse scientific domains, methodologies and epistemological approaches. Such reflection will be fuelled by examples of the authors’ personal dance research engagements, as, for instance, when two authors of this paper (E.M. and M.P.) danced together and developed a video which served as complementary material to their related manuscript submission to an academic journal[1] (Mandalaki & Pérezts, 2022). Through such practices, we hope to enhance the impact of the workshop by targeting not only the “Dance your Ph.D.” contest but also other types of scientific communication, research and pedagogical approaches using choreography and embodied and dance-based methods more broadly.

Choreographic Tools

In the tables above we listed the different choreographic tools, such as dancing levels and experimenting with tools, which we used and adapted to online teaching. Many of these tools were highlighted by the participants’ feedback along with reflections on the physical modalities used and their interactions with the online format. Some of these adaptations dovetailed with those of Zihao Li (2020; 2023), who also had to move their dance teaching online during the pandemic. Specifically, after the first workshop, participants reported that they would have liked to receive more tools to help them turn their research and abstract ideas into choreography. For the second workshop, we therefore introduced storyboards and how to use them. We plan to further integrate students’ feedback to provide the desired practical tools that allow students to choreograph their research through dance videos (McPherson, 2018).

Self-Confidence to take part in the Workshop and Contest

In their feedback (UCLouvain, 2022), Ph.D. participants described the caring and constructive mood they experienced during the workshop, allowing them to learn and feel psychologically safe enough to actively participate in the sessions, regardless of their level as either dancers or academics. For example, we used a series of body-consciousness and expressivity exercises that do not require any special training or physical abilities, instead of elaborate dance techniques. These were performed in a climate of trust, constructing a safe space within which participants would feel comfortable to ‘loosen up’ their bodies and find ways of expressing their research. The feedback also identified some room for improvement. First of all, starting the workshop with an online session was seen as problematic as it made it harder for participants to fully commit themselves to the workshop from the start. Indeed, the topic and method of the workshop are unusual for this audience, especially in the online format. To leverage the benefits of a hybrid format, as mentioned above, in future we plan to start with two days of in-person sessions to give participants the opportunity to engage physically with the process and interact together before moving to online sessions. This might allow participants to get to know each other and start establishing some common ground for physical connection, trust in their abilities and in each other, as well as exchanges of support in relation to their varied research processes.

Finally, one of the most positive outcomes of our experience is that for the first time in the history of the “Dance your Ph.D.” contest, three UCLouvain Ph.D. students entered dance videos in the Social Sciences category of the official contest (Delanaye, 2021; Solbreux, 2021; Wu Mandal, 2022), and more plan to do so in the future. This might serve as a demonstration of how participation in this workshop can enhance students’ belief and confidence in their abilities to conduct and disseminate their academic research differently, creatively, and meaningfully. Students feel supported and encouraged to engage with embodied learning, success and failure, which admittedly makes them aware of their embodied, physical, and intellectual potential, equipping them with the necessary qualities to engage confidently with their work.

Considering the above, the positive impact of this workshop gives us hope and motivates us to continue experimenting with these creative possibilities and integrating students’ feedback to further develop the workshop internationally, across different audiences, in years to come. Building on what we have learned, we encourage future researchers to further explore the possibilities and limitations of hybrid or fully virtual formats in choreographing academic research practices, not only among homogenous groups of students but also across geographies and institutions, in consideration of participants’ differences and intersectional positionalities.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author (N. K.) would like to thank Mrs. S. Baudine and the administrative team of the Louvain Research Institute of Management and Organizations for their support of this project and help in organizing the workshops.

Notes

References

- Bohannon (2014, November 11). Dance vs. powerpoint, a modest proposal [Video]. TEDxBrussels. https://ted.com/...

- Delanaye, L. [Lyse] (2021). Dance your Ph.D. 2020-2021: Roman and Byzantine weights from the Iberian peninsula. YouTube. https://youtu.be/F60wmhIvB-o

- Garoia, V., Gras-Velázquez, À., Stefanica, D., & Stone, M. (2014). The Second Scientix Conference – The results. European Schoolnet. http://eun.org/...

- Godoi, M. R., Kawashima, L. B., Gomes, L. d. A., & Caneva, C. (2021). Les défis et les apprentissages des formateurs d’enseignants d’éducation physique pendant la pandémie de COVID‑19 au Brésil. Revue internationale des technologies en pédagogie universitaire, 18(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.18162/ritpu-2021-v18n1-03

- Hernández Castro, G. Z. [Gea Zazil] (n.d.). DanScie – Laboratorios de danza y cienca. Gea Zazil Website. Retrieved November 4, 2023, from https://geazazil.wixsite.com/...

- Hernández Castro G. Z. [Gea Zazil] (2021). VidéoconféDANSES. ChorégraKIDS. Retrieved November 4, 2023, from https://geazazil.wixsite.com/...

- Hernández Castro, G. Z. [Gea Zazil] (2022, November 22). RETORNO – ZAZIL – MedexMuseum 2022 [video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/abmvq3AmrZ4

- Jääskeläinen, P. (2023). Research as reach-searching from the kinesphere. Culture and Organization, 29(6), 548-563. https://doi.org/k9m2

- Jääskeläinen, P., Laine, P.-M., Meriläinen, S. & Vola, J. (2023). Chapter 4. Embodied bordering: Crossing over, protecting, and neighboring. In M. B. Calás & L. Smircich (Eds.), A research agenda for organization studies, feminisms and new materialisms (pp. 73-94). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/k9m3

- Kaasila‐Pakanen, A. L., Jääskeläinen, P., Gao, G., Mandalaki, E., Zhang, L. E., Einola, K., Johansson, J., & Pullen, A. (2023). Writing touch, writing (epistemic) vulnerability. Gender, Work & Organization, 31(1), 264-283. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.13064

- Kervyn, N., Bogaerts, C., Guisset, M., & Vangrunderbeeck, P. (2022). Transition numérique d’un cours d’introduction au marketing : conception d’un dispositif d’enseignement mixte adapté à la méthode des études de cas. Revue internationale des technologies en pédagogie universitaire, 19(3), 80-89. https://doi.org/10.18162/ritpu-2022-v19n3-05

- Leavy, P. (2020). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Li, Z. (2020). Teaching introduction to dance studies online under COVID-19 restrictions. Dance Education in Practice, 6(4), 9-15. https://doi.org/grnkms

- Li, Z. (2023). Shifts in pedagogy and autonomy in virtual dance teaching and learning. Journal of Dance Education. https://doi.org/k9m5

- Lozano, M. (2021, May 6). Danza en planta libre: Diario de un cuerpo en quarantine [Blog post]. Revista Escafandra. https://escafandrauabc.wordpress.com/...

- Mandalaki, E. (2019). Dancers as inter-corporeality: Breaking down the reluctant body. In M. Fotaki & A. Pullen (Eds.), Diversity, affect and embodiment in organizing (pp. 139161). Springer. https://doi.org/mbcf

- Mandalaki, E. (2023). Invi(α)gorating reflexivity in research: (Un)learnings from α field. Organization Studies, 44(2), 314-320. https://doi.org/mbcg

- Mandalaki, E., & Daou, E. (2021). Writing memory work through artistic intersections. Unplugged. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(5), 1912-1925. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12720

- Mandalaki, E., & Pérezts, M. (2022). It takes two to tango: Theorizing inter-corporeality through nakedness and eros in researching and writing organizations. Organization, 29(4), 596-618. https://doi.org/gmcpjm

- Mandalaki, E., van Amsterdam, N., & Daou, E. (2022). The meshwork of teaching against the grain: Embodiment, affect and art in management education. Culture and Organization, 28(3-4), 245-262. https://doi.org/mbch

- McPherson, K. (2018). Making video dance: A step-by-step guide to creating dance for the screen (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/mbcd

- Parrish M. (2008). Dancing the distance: iDance Arizona videoconferencing reaches rural communities. Research in Dance Education, 9(2), 187-208. https://doi.org/dwbhvn

- Pérezts, M. (2021). Three walls. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S2), 510-514. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12664

- Pérezts, M. (2022). Unlearning organized numbness through poetic synesthesia: A study in scarlet. Management Learning, 53(4), 652-674. https://doi.org/mbcj

- Plasson F. (2018). La vidéo-danse sur Internet: l’exemple de Numeridanse. Repères, cahier de danse, 2018/1(40), 10-13. https://doi.org/10.3917/reper.040.0010

- Science. (2023a). Announcing the annual Dance Your Ph.D. contest. Retrieved April 14, 2023, from https://science.org/...

- Science. (2023b). Official rules for Dance Your Ph.D. contest. Retrieved April 14, 2023, from https://science.org/...

- Solbreux, J. [julie sol]. (2021, January 27). Education through social entrepreneurship: An integrated identity construction – Dance your Ph.D. 2020 [Video]. YouTube. http://youtu.be/xBoxEnHkyZg

- Spry, T. (2016). Body, paper, stage: Writing and performing autoethnography. Routledge.

- UCLouvain. (2022, September 16). What did they think of our Dance your Ph.D. workshop? Louvain Research Institute in Management and Organizations – News. https://uclouvain.be/...

- Un desierto para la danza – Programa general. (2015). Secretaría de Educación Pública. https://issuu.com/...

- Wu Mandal, Y. (2022, January 28). Dance Your Ph.D. 2022: How do Chinese adolescents resist their parents when feeling over-controlled? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/cxNTkrORLKI

List of figures

Figure 1

Online Backlight Dancing Exercise

Figure 2

Dancing Experimentation Using Teams Background

List of tables

Table 1

Program for December 2020 Online Workshop

Table 2

Program for September 2022 Blended Workshop