Abstracts

Abstract

The expansion of platform work has disrupted and reordered employment regulation. The literature has contributed to this subject from different angles, although often in a fragmented way and without clearly explaining why and how regulatory conflict arises over platform work. Using Beckert's (2010) framework for study of how fields change, the author conducted a critical literature review on: 1) the roles of institutions, networks and frames in regulating platform work; 2) the regulatory power these structures provide to actors and organizations; and 3) the possible interrelationships between these structures. The results show the existence of a substantial literature on the scope of institutional regulation and the regulatory power of networks, but much less on the broader role of the state in this field, and the framing processes that guide the actors’ preferences for regulation. Future lines of research are discussed.

Summary

In this article, a critical review of the literature identifies which state and non-state actors and organizations influence and shape regulatory conflict over platform work, and which resources enable them to intervene.

These questions are addressed by examining the different forms of embeddedness that interact and shape the regulatory process. Drawing on the framework that Beckert (2010) proposed to explain changes in market fields, this literature review identifies three dimensions of research that emphasize the roles of institutions, social networks and cognitive frames, respectively. It also discusses to what extent the literature on platform work has developed an integrated perspective on regulation and how the field of industrial relations can benefit from the incorporation of different dimensions of research.

The literature search was conducted using the main available databases and grouped into the three main dimensions of the framework. Influential policy reports and grey literature in the field of study were also included. In total, 149 documents were reviewed in depth.

The literature has primarily focused on discussing the scope and applicability of existing labour regulatory frameworks and the increasingly important role of strategic litigation. There has also been a remarkable research strand on the regulatory power of platform firms and on new forms of governance. There has been much less critical research on the state's role in the expansion of the platform economy and on how different actors legitimize the regulatory process.

This paper applies a three-dimensional framework to the literature to facilitate dialogue on three social structures that influence platform work regulation, the aim being to explain the emergence of regulatory conflict in this area. The framework captures both formal and informal forms of regulation, making it useful for the industrial relations literature as well.

Keywords:

- platform work,

- regulation,

- regulatory conflict,

- critical literature review

Article body

1. Introduction

Platform-mediated work has grown rapidly over the last decade, as it provides an easy-to-access and flexible source of income for people worldwide (Heeks, 2017; Berg et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2019). Although the platform economy still accounts for a small proportion of the labour market (Azzellini et al., 2022), it has rekindled debates on the liberalization of labour relations, the re-commodification of work, new forms of algorithmic control and the rise of “winner-takes-all” markets where large players undermine competition (Azzellini et al., 2021; Srnicek, 2017; Grimshaw, 2020). Moreover, it has been stated that such forms of work erode the standard employment relationship and are highly unprotected (De Stefano, 2016; ILO, 2021). New regulatory efforts are thus being made worldwide (Aloisi, 2022; De Stefano et al., 2021), especially to regulate location-based platforms, such as those that provide ride-hailing and delivery services.

Landmark rulings have acknowledged the existence of an employment relationship between workers and platforms, and new laws are being proposed to protect certain groups of workers. Several examples may be given. The AB5 statute passed in California in 2019 extends the employee classification benefits to most wage-earners. However, the heavily lobbied Prop 22 ballot granted an exception for delivery and ride-hailing firms. Spain's new "Rider Law" (decree 12/2021) presumes that delivery workers are employees, an outcome of social dialogue between major trade unions and employers’ associations. Similarly, Chile’s Act 21.431 from 2022 regulates contracts for workers on digital service platforms, following the agreements reached in a Technical Roundtable in which various industrial relations actors participated. Finally, the new Platform Work Directive, now being debated in the European Union, aims to clarify gig workers' access to labour rights (Buendia Esteban, 2023). There is thus an emerging a contentious scenario in which a myriad of organizations and actors, within and beyond the state, are creating and shaping the regulatory process (Kirchner & Schüßler, 2020). This reality calls for a more comprehensive understanding of what we understand by “regulation” in a broader sense and how these different players (formal and informal regulators) influence and relate to each other.

From an industrial relations standpoint, platform work is certainly regulated by formal and informal rules (and actors), regardless of how the employment relationship is legally categorized (Joyce et al., 2022, p. 3). This growing role of informal relations and non-institutional actors in regulation is not entirely new. With the liberalization of markets, regulation is becoming not only more market-oriented but also “multifaceted, differentiated and increasingly ‘shared’ by a range of public and private actors” (Martinez Lucio & MacKenzie, 2004, p. 78). This trend compels us to take a closer look at the social processes that surround regulatory change, an issue that the field of labour law has only addressed discretely (Dukes, 2019). Although different disciplines and fields have studied the issue from specific angles, it is crucial to understand how they complement each other. I am thus offering a critical and comprehensive literature review to show how conflict has arisen and to identify gaps in academic discussion that require further research.

I present the following research question: which state and non-state actors and organizations have influenced and shaped regulatory conflict over platform work, and what sort of resources have enabled them to intervene? To address this enquiry, I suggest using Beckert's (2010) framework to study change in market fields and to theorize the roles of three major social structures: institutions; social networks; and cognitive frames. It will thus be possible to contextualize the regulatory process as politically contentious and socially underpinned. To analyze the academic literature, I will adopt a deductive approach that considers which of these social structures has been emphasized and how the actors have exploited the resources provided by each structure. I will argue that one-dimensional or partial understandings of regulation have prevailed in the literature, while highlighting those contributions that have established connections between the roles of different social structures. Such an approach will not only provide a better understanding of the regulatory challenges but also help explain why and how conflicts have arisen over regulation. Finally, I will emphasize the analytical value of the framework, especially for research in industrial relations.

2. Studying Regulatory Change as Embedded in Social Relations and Structures: The Role of Institutions, Networks and Frames

I will examine regulation in a broad sense, including the interplay of actors and narratives that shape the regulatory process, using Beckert's model to study the literature. He primarily sought to understand how market fields change, a “field” being defined, per Fligstein (2001), as a local social order "where organised actors gather and frame their actions vis-a-vis one another" (p. 108). As with Bourdieu’s definition, a field is understood as a structured social space governed by its own set of rules and norms, although more emphasis is on the role of organizations and institutions in shaping economic activity (Fligstein & McAdam, 2011, pp. 19-21). The concept of field has been influential in bridging the gap between the industrial relations literature and the organization studies literature, as seen for example in Helfen’s (2015) research on changes to regulation of agency work in Germany. The author identified the main actors (incumbents and challengers) and how they competed to redefine the boundaries of regulation and the construction of distinctions between groups of workers in the legislation. For its part, Kirchner and Schüßler (2020) applied the concept of field to understand the regulatory challenges of for-profit platforms, revealing how existing regulations are undermined by the loose coupling of organization, place, workforce and product. The two authors identified the actors in regulatory issues, including platform companies (as market organizers), national and local governments, private actors and civil society organizations. Because the platform economy is made up of various organizational actors and different modes of governance (p. 228), the concept of field helps explain how regulatory conflict arises by enabling us to examine the agency of different actors and interests and how they intervene concurrently.

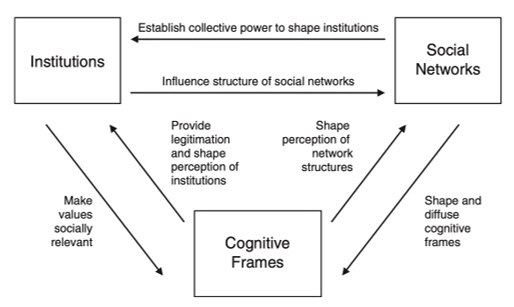

Beckert (2010) posited that a field is composed of three interdependent social structures that cannot be studied separately: institution; social networks; and cognitive frames (Figure 1). Institutions encompass the rules and regulations that dictate behaviour among actors. Social networks refer to the structural position of actors and organizations. Cognitive frames are the mental organization of meanings and social norms used by actors to assess and behave in markets. Each structure provides resources that different actors and organizations can use to intervene and shape change. Beckert argued that these three structures work together within a field, thereby providing an integrated perspective on social embeddedness. He thus offered a framework to reconcile the opposing positions of a fragmented debate, including also general descriptions of how each structure influences the others.

Figure 1

Reciprocal Influences of the Three Structures in Market Fields

By using this framework, we can explore research that has focused on institutions, networks and frames, and examine their (potential) interrelationships. In this sense, the framework is innovative and relevant in that it suggests delving into the role of these three different social structures to explain how regulatory conflict arises in a “field.” While institutions and the state are generally considered to be key players in regulatory processes, networks and frames likewise regulate the platform economy in ways that should not be overlooked. The importance of networks in the success of platform businesses has been widely acknowledged (e.g., Parker et al., 2016), while narratives on entrepreneurship, flexibility and regulatory legitimacy have played a significant role in policy debates (e.g., Gillespie, 2018; Tzur, 2019). However, it is important to determine the extent to which these issues have been addressed in the specific context of regulation of platform work.

I will accordingly first examine how the literature on platform work regulation has conceptualized each social structure and how actors have used their unique power resources to influence regulation. I will then explore the extent to which reciprocal influences between the structures have been studied. Here I argue that the literature on platform work requires further research into the interactions between networks and frames with institutional regulation and the state, in order to better understand why responses to issues such as legal classification, regulatory models, and enforcement differ significantly between local and national cases. Such differences highlight the importance of examining all three structures to comprehend how regulatory conflicts are shaped and framed in each country and context. Finally, I will discuss future lines of research, state the limitations of my review and make concluding remarks.

3. Method: Critical Literature Review

I carried out a critical literature review to answer the following question: which state and non-state actors and organizations influence and shape regulatory conflict over platform work, and which resources enable them to intervene? This type of literature review differs from other approaches, such as bibliometric or meta-analysis. The aim is not simply to identify and describe the main research trends, strands and evidence on a specific topic; rather, it is to assess the degree to which some controversial issues have been resolved through research. The aim is also to identify missing, incomplete or poorly represented points, as well as potential inconsistencies or divergences between different perspectives (Torraco, 2005, p. 362). Thus, my analysis is also a reflection on the literature, and not just a descriptive account of all its topics.

Due to the vast literature available on platform work and the word limit of this paper, I have focused on major debates rather than on specific points. For this, I have used previously established concepts and theories to categorize the literature by topic (Saunders & Rojon, 2011). This type of literature review provides greater flexibility for a deductive approach, where the literature's contributions are evaluated within an explicit framework, such as Beckert's. This approach helps not only to assess the importance of each structure in regulatory conflict but also to uncover missing points on the interrelationships between the three structures.

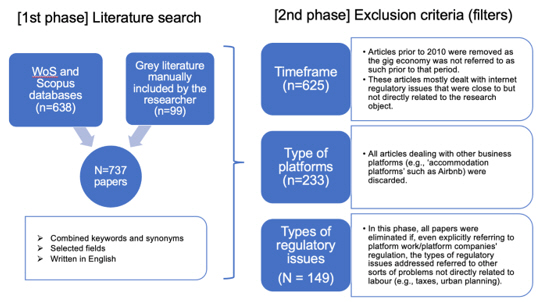

The literature search and subsequent selection were organized in two phases (Figure 2). In the first phase, I constructed a database of papers from two information sources. The first and foremost source encompassed the two most reputable social science databases: Web of Science and Scopus. I searched the literature by combining two terms: “regulation” and “platform work.” Both terms had to appear in the title, abstract or keywords. In addition, I considered some synonyms of both keywords: “institutional change” and “legislation” instead of “regulation” and “crowd work,” “gig work,” “gig economy” and “sharing economy” instead of “platform work.” Because these terms are not equivalent, and because there is no consensus in the literature on their use (Howcroft & Bergvall-Kåreborn, 2019), I was as exhaustive as possible in the search and then narrowed down the literature in the second phase by excluding those papers not directly related to the research topic.

I focused primarily on journals in industrial relations and labour law but also included those in business, management and social sciences. Although the literature review was focused on regulation of platform work, some topics, especially those referring to the role of cognitive frames or social networks, may not necessarily appear in journals that specialize in regulatory issues, appearing instead in various social science journals. Also, the papers had to be written in English. The first search identified 638 relevant papers after I checked and removed duplicate entries.

The second information source was the grey literature: policy reports by international institutions (e.g., the ILO); book chapters; and papers from law journals not indexed in the above databases. Also included were some papers that were found not through the initial review but in the reference lists of influential papers. In total, 99 more papers were added. Thus, the total rose to 737 papers.

In the second phase, the database was narrowed down for a more in-depth analysis, on the basis of three exclusion criteria. First, I excluded papers published before 2010, on the assumption that gig economy research was limited at that time. Second, I excluded companies engaged in types of business that do not involve gig work directly, such as accommodation or e-commerce platforms. Third, I excluded papers that addressed regulatory issues other than labour issues, the latter defined as those relating to labour misclassification, social protection, collective bargaining, discrimination and algorithmic transparency in personnel management decisions. The total was thus reduced to 149 papers (see details below).

Figure 2

Data Collection

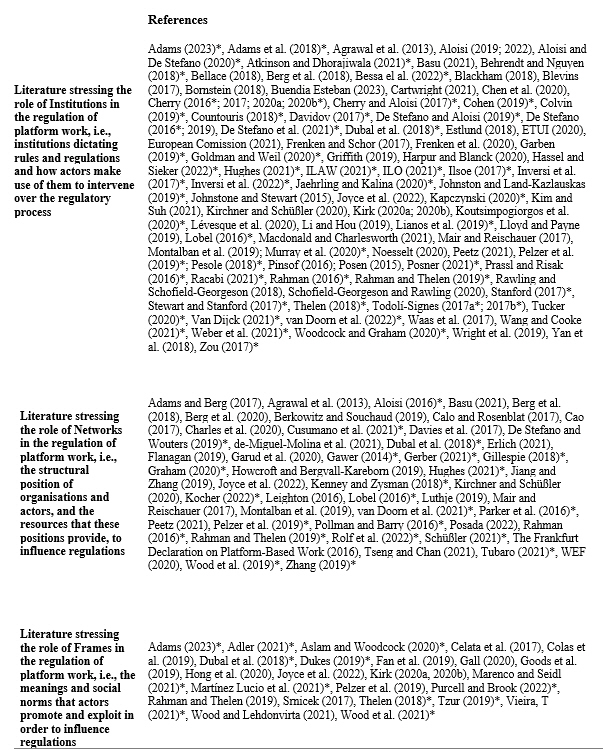

In reviewing these papers, I identified key themes, which in general referred to such issues as the scope and possible applications of labour law instruments, strategic litigation, corporate power and influence over platform regulation and actors' preferences on labour status and their vision of legislation on the platform economy. When a paper clearly referred to any of these issues, it was included in one of the three social structures of the framework: institutions; networks; or frames. If the paper addressed more than one issue, it was coded as belonging to more than one structure category (see the appendix for details). This multiple-coding issue is covered in detail in the discussion section, where I analyze the extent to which the different structures interrelate with each other. Based on these themes, I present a synthesis of the discussions, highlighting the strengths of regulation and the room for improvement to regulation of each social structure.

4. Results

4.1 The Crucial and Multifaceted Role of Institutions in Platform Work Regulation

This section discusses the literature on the role of institutions in regulating platform work and the actors who use institutional resources to intervene in the regulatory process. Although institutions evidently have some importance in any regulatory process, the literature has had to challenge the belief that corporate power in the digital age has gone unchecked in the absence of regulation (Cohen, 2019; Kapczynski, 2020). In fact, regulatory institutions have played a critical role, either by limiting the space for central disputes over recognition and access to labour rights (ILO, 2021; Pesole et al., 2018) or by enabling the expansion of these business models (Rahman & Thelen, 2019). Some of the main currents in this literature are reviewed below.

Legal scholars have paid significant attention to the legal classification of platform workers as employees, as independent contractors or as a distinct category altogether (Adams et al., 2018; Aloisi & De Stefano, 2020; Koutsimpogiorgos et al., 2020; Stewart & Stanford, 2017; Todolí-Signes, 2017a; Zou, 2017). This classification has important implications for their labour rights, including freedom of association, collective bargaining, protection against discrimination (De Stefano & Aloisi, 2019) and health and safety issues (Garben, 2019). As with other categories of “self-employed” persons or workers in grey zones of the labour market (Jaehrling & Kalina, 2020; Stanford, 2017), the legal challenge is to demonstrate whether the worker is sufficiently controlled or subordinated to be considered an “employee.” This is notably the case with the new forms of algorithmic management (De Stefano et al., 2021). The challenge is certainly a topical one, as national and local jurisdictions are unevenly equipped to regulate work of this nature (Aloisi & De Stefano, 2020). Some countries have a hybrid or intermediate third category, and others still rely on a dual system (Cherry & Aloisi, 2017; De Stefano, 2016; Wang & Cooke, 2021). While landmark rulings in different countries have created some baseline jurisprudence (Moyer-Lee & Countouris, 2021), there are still ongoing court cases, and cases of misclassification have often been resolved out of court (Cherry, 2016). Consequently, some scholars and organizations have advocated securing basic rights for platform workers regardless of their legal classification (Behrendt & Nguyen, 2018; Countouris, 2019; ILO, 2021; Todolí-Signes, 2017b).

Courts and scholars have taken different approaches to determining the type of employment relationship beyond the traditional one of employee versus independent contractor. Some have favoured a "purposive approach": interpret labour law in line with its purpose of protecting workers and their rights; this applies to platform workers who work on a dependent and subordinate basis (Atkinson & Dhorajiwala, 2021; Davidov, 2017). Others have suggested to incorporate a "functional concept" of the employer: instead of just looking at whether workers are legally classified as employees or not, this approach would assess whether platforms perform the typical roles of an employer (Prassl & Risak, 2016). Misclassification also raises concerns about power asymmetry in a broader context, as some competition laws prohibit self-employed workers from participating in coordinated negotiations, such as collective bargaining, even though such workers are economically dependent on the platform as if they were employees (Lianos et al., 2019; Johnston & Land-Kazlauskas, 2019; Posner, 2021). Addressing these issues and expanding worker rights is crucial to ensuring basic rights and conditions and to experimenting with new forms of organizing and bargaining for non-standard workers (Rahman, 2017).

The literature on platform work also highlights the significance of a political economy perspective in examining the institutional conditions that promote the growth of platform work (Ilsøe, 2017; Thelen, 2018; Tucker, 2020). Although this perspective encompasses a relatively smaller body of research, it has been influential. For example, Rahman and Thelen (2019) identified various factors that have led to the development of the American platform business model, such as a permissive political-economic framework, a supportive legal system and a financialized business sector willing to promote such investments. In a comparative analysis of the UK, the US and Germany, Hassel and Sieker (2022) explored the institutional determinants that affect the expansion of gig contracts, finding that, paradoxically, the universal welfare state has facilitated the expansion of gig contracts in the logistics and service sectors. However, this dynamic may differ significantly in contexts with a larger informal economy. In a study of Mexico and Panama, Weber et al. (2021) observed that platforms often recruit workers from the informal sector, while helping formalize the labour market because the company has to comply with legal operational requirements. Thus, platform work can both degrade working conditions and offer new opportunities for those in need of work, particularly migrant labour (van Doorn et al., 2022). The political economy perspective therefore provides a broader understanding of platform work, as the debate on employment classification by itself seems insufficient.

Finally, a strand of research has looked at the agency and resilience of different actors, particularly workers, in using institutions to gain power and confront platform companies. Here, scholars have stressed the importance of strategic litigation as a source of power for workers (Adams, 2023; Cherry, 2020). Such litigation, however, has to reckon with one critical barrier: the international scale on which platforms operate (Inversi, 2017; Racabi, 2021), which has enabled them to avoid lawsuits by arguing that the company is subject to a different country's jurisdiction (Woodcock & Graham, 2020). Bessa et al. (2022) reviewed the research on platform labour unrest, showing that trade unions and gig workers’ organizations have mostly sought to regulate through legislation and legal enactment. There is, however, global unevenness on these experiences, as institutional responses seem to follow a more progressive direction in Europe than elsewhere (van Dijk, 2021). On a more theoretical level, researchers have also examined the extent and scope of these efforts to use institutions and even experiment with new regulations (Murray et al., 2020).

All in all, a great body of research has shown how institutions play a significant role in the regulation of platform work. A crucial question which is certainly derived from all of this, but which remains to some extent open-ended, is how the state is conceptualized within these debates. In this vein, the work of Inversi et al. (2022) showed how state and non-state UK actors are taking over or giving up regulatory spaces in the gig economy. This approach, though still relatively scarce in the literature, could broaden discussion of the state's role and its relationship with various actors, by going beyond debate centred on certain legal instruments that tend to target the state more narrowly.

4.2 Social Networks: Growing Regulatory Influence of Markets and Non-State Actors

In this section I will discuss the popularity and concrete uses of the “network” concept in the literature on platform work and platform markets, with two caveats. First, although there is an abundant literature on the topic of networks in general, few of these papers directly address regulation of employment issues or digital labour platforms. Second, the network concept is quite broad and gives rise to slightly different issues in the literature. I will then go on to review two specific concepts that relate to networks and platform work regulation: "network effects" and "network embeddedness." The former has been extensively studied in the industrial relations and political economy literatures and relates to the impact of networks on platform’s market dominance. The latter is closer to the concept outlined by Beckert in his framework and has been extensively used in economic sociology. While there may be other discussions on networks and corporate power, this section will focus on these two network-specific concepts.

The concept of “network effects” has been widely discussed in the literature that understands platforms as markets, where the benefits of the network increase with the number of actors connected to the platform (see Gawer, 2014 for an extended discussion). Platform design is meant to create market dominance, becoming the “central agents at the nexus of a network of value creators" (Cusumano et al., 2021, p. 1260), which is seen as essential to the business model (Rahman & Thelen, 2019; Rahman, 2016). This situation fuels competition but also creates incentives for greater value capture and market dominance, often resulting in winner-take-all markets (Kenney and Zysman, 2018; Parker et al., 2016). Through this new conception of networked dominance over "multi-sided markets," platform firms have challenged the predominance of classical employment contracts and imposed private business contracts, thus causing a definitional disruption in labour law (Lobel, 2016; Kocher, 2022). Hence, workers are excluded from labour rights through a business model that exploits these legal gaps to circumvent existing regulations (ILO, 2021; pp. 198-202). Consequently, some commentators are calling for a broader perspective on regulation, as they look at the emerging power of these new private actors and argue that the state is not the only source of normative authority (Rolf et al., 2022). For example, platform firms are incentivized to promote self-regulation while avoiding interference from regulatory institutions by implementing non-compliance monitoring policies and corporate social responsibility programs. However, in practice, the potential reduction of network effects often discourages such efforts by platform firms, as discussed by Cusumano et al. (2021).

On the other hand, the concept of “network embeddedness,” originating in sociology, has also been useful in debates about regulation. According to Wood et al. (2019), platform workers, despite being normatively (or legally) dis-embedded, are concurrently embedded within interpersonal networks of trust that workers generate to overcome the low-trust nature of non-proximate labour relations in the gig economy. Social ties play a key role in community building, resistance and self-regulation among workers (Gerber, 2019). Tubaro (2021) similarly suggested that these interpersonal networks coexist with other economic networks of ownership and control, thus enabling platforms to fulfil different market functions (Schüßler et al., 2021), including management-labour relations. It is in some of these specific functions that regulatory problems are more common, particularly when platforms exercise their power to direct and control work.

The literature also shows a growing interest in understanding how actors engage and participate in platform networks. They engage and participate partly because their governance structures often incorporate inputs from user groups, industry bodies and civil society organizations (Gillespie, 2018). Their regulatory power and influence thus seem to come from an even more extensive network. In fact, these corporations have been described as "regulatory entrepreneurs," as their market insertion often involves a plan to significantly change market regulation (Barry & Pollman, 2016). While such change is often achieved through traditional political lobbying, it also includes more sophisticated strategies, such as mobilizing certain groups from the network, especially user or consumer groups. Examples include Uber's tactics to act on legislation in the US (Hughes, 2021; Thelen, 2018), the Netherlands (Pelzer et al., 2019) and China (Zhang, 2019). Similarly, platforms actively seek to garner the favour of civil society in order to avoid any regulation. For instance, van Doorn et al. (2021) showed how platforms in various cities have established non-profit partnerships with civil society organizations in the food delivery and social care sectors to provide the necessary infrastructure to bring supply into line with demand and reach the socially disadvantaged. Through these partnerships, the platforms have expanded their business scope considerably, even participating as social partners in services delivered by the state. It might be said that platforms, in and of themselves, have an ephemeral regulatory power that depends on the active participation of civil society in the market they provide (Graham, 2020).

To sum up, the literature has successfully explained how platform networks have gained the ability to influence debates about regulation, but such influence requires building social legitimacy with different actors, especially consumers and workers. It is thus complicated to determine whether regulatory responsibilities should be allocated to platforms (Aloisi, 2016; De Stefano & Wouters, 2019), as a platform is supposedly a network of different actors and organizations freely engaging in business. Moreover, when it comes to employment regulatory issues, the very concept of networks requires more clarity because it blurs the employment relationship (Marchington et al., 2005). Finally, the state tends to be seen from a passive perspective, subject to the influence of networks, but less is said about how the state also shapes the regulatory space in which the networks operate. Therefore, incorporating the concept of networks into a theory that understands the state as a complex and decentred web of institutions and actors presents a theoretical and empirical challenge.

4.3 Cognitive Frames: Narratives and Social Meanings that Underlie Regulatory Conflicts in Platform Work

In the last section, I analyzed the role of cognitive frames—the organization of meanings and social norms that guides how actors behave in a market. In line with this idea, and as previously discussed, the position of actors within platform networks is crucial not only for their competitive advantage (network effects) but also for their ability to articulate the positions of interests that seek to influence regulation by proposing or opposing legislation. In fact, platforms have successfully linked themselves to a powerful narrative that legitimizes their disruptive growth by challenging regulation (Dubal et al., 2018; Marenco & Seidl, 2021; Srnicek, 2017; Rahman & Thelen, 2019). There is thus a literature that explores how actors influence regulatory action by framing the debate, that is, by determining which arguments prevail and which audiences resonate with these frames. In the following section, I will delve into some of these approaches with respect to platform work.

In her study of Boston's ride-hailing industry, Adler (2021) took up the idea that "frames shape perceptions of regulatory legitimacy" (Avent-Holt, 2012, quoted in Adler, 2021, p. 1422) by resonating with certain audiences and thus challenging the legitimacy of governmental regulatory function. Her research shows that, in the face of demands for compliance with employment and transport laws, such companies mount media campaigns that accuse governments of protecting the taxi industry and thus preventing competition. They thereby shift the focus of the debate from the legitimacy of their business activity to the legitimacy of the regulation, thus creating a meta-frame that challenges the regulatory process as a whole. Other studies have documented similar deregulation campaigns in different countries (Dubal et al., 2018; Thelen, 2018; Pelzer et al., 2019; Rahman & Thelen, 2019; Tzur, 2019).

Another major strand has been the literature on the different attitudes of platform workers toward regulation. Research has revealed a complex relationship between, on the one hand, demands for stability and security and, on the other, an interest in flexibility and entrepreneurial freedom (Dubal et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2021). Labour organizations pursue different interests in relation to regulation, with some seeing legal action and litigation as an opportunity to revive discussion of worker collectivism and activism in the gig economy (Gall, 2020; Adams, 2023; Aslam & Woodcock, 2020). For some, workers mobilize against the state to be recognized as workers in the absence of a recognizable employer figure (Martinez Lucio et al., 2021). For others, actors blame work-related injustices sometimes on the state and sometimes on the market—either the platforms or the customers (Wood et al., 2021). Some studies have documented cases of workers organizing against regulation, specifically the classification of employment contracts, in order to safeguard their status as independent contractors. An example would be the si soy autonomo (yes, I am self-employed) movement in Spain which took place prior to the enactment of the new regulation (Vieira, 2021).

By introducing the concept of “governmentality,” Purcell and Brook (2022) helped explain the emergence of these ideologies among gig workers, and the impact on how these actors frame the regulatory problem. The authors asked why, despite its well-documented exploitative nature, platform labour is still understood by many, both workers and other actors alike, as a way of gaining control and autonomy over one’s working life. Specifically, the authors studied how consent in the labour process and production of hegemony from institutions outside the workplace are concurrently produced and internalized in subjects, thus shaping their sense-making of the social world. They explained "how hegemony is constructed through techniques of power at macro-levels (government policy and discourse) and meso-levels (platforms) that shape individual subjectivity by normalising dominant understandings of the social world and behaviour" (Purcell & Brook, 2022, p. 402). This approach offers an opportunity to explore the concept of regulation through forms of power anchored in both institutions and networks that shape frames (here understood as macro- and meso-level powers), without prioritizing one form of power over another but suggesting that they operate concurrently and are internalized in subjects.

Overall, there has not been as much research on the role of frames in debates about regulation as there has been on the roles of the other two structures, but it has still been prominent. Such research has provided empirical studies and theory on the politics of platform regulation, thus helping explain the elusive nature of the gig economy for regulation and the difficulty in debating these issues in the public sphere. While regulations have adopted functional or purposive approaches, prioritizing facts over stakeholder beliefs (or at least they intend to), frames are often formed and disseminated at an earlier stage of an inherently political regulatory process. This stage decides how such debates are positioned within the state and the political arena, the relevance and legitimacy of addressing them and the labels or definitions used to construct the legal debate. These factors go beyond the legal debate itself and relate to the formation of the field in which platform work is regulated.

5. Discussion: Interrelationships of Institutions, Networks and Frames in the Regulation of Platform Work

The previous three sections have provided an overview of debates about regulation of platform work, with different authors emphasizing respectively the roles of institutions, networks and frames. Just as Beckert argued that we must look at the interrelationships among the three structures to explain market change, I argue that these interrelationships must also be understood to explain how conflict arises over regulation of platform work. Throughout my literature review I have shown how state and non-state actors and organizations influence and shape such conflicts by using resources from institutions, networks and frames. The interconnections between these structures are not necessarily explicit or clear in the literature, partly due to the expected differences between disciplinary approaches, but also due to the lack of clearer theorization of the regulatory process. Because of space limitations, I will mention only a few papers that I believe provide very interesting insights into a more integrative industrial relations approach.

Going back to Figure 1, in the case of institutions, the main concern is how they “influence the structure of social networks,” on the one hand, and “make values socially relevant,” on the other. The first point is addressed by Inversi et al. (2022), who showed that, in the UK case, the state has been delegating functions to other public and private actors and institutions to set employment standards in the gig economy. Thus, the imperatives of accumulation strongly influence the forms of regulation that emerge. In a similar vein, it has been argued that managerial interests have been colonizing the regulatory space; private arbitrators have gained, within legal institutions, a space formerly controlled by the state (Cohen, 2019). In other words, the regulatory power of networks should be understood not as a substitute for state power but rather as a way in which the state concedes authority to non-institutional actors and networks and thus broadens its spheres of intervention. On the roles of institutions and frames, Inversi et al (2022) showed how the state prioritizes certain values and frames over others. This has been the case with a government commission that defines good labour practices in platform work, known as the Taylor Review. It has been more inclined to engage with corporate actors than with trade unions and grassroots worker organizations. Thus, contrary to the narrative of state withdrawal from regulation, the state has played a role in crafting a predominantly pro-business voice, while hidden in a technocratic guise, a role that other authors have described as state engagement in the “conduct of conduct” of neoliberal subjects (Purcell & Brook, 2022).

When it comes to social networks, the main aim has been to understand how they influence institutions by “establishing collective power to shape them” and frames by “shaping and diffusing” specific narratives within and through networks. The first point—the influence of networks on institutions—seems to be well analyzed: platforms are “regulatory entrepreneurs” that first inhabit the grey areas of corporate and labour law until they become powerful enough to influence how those regulatory loopholes are filled (Pollman & Barry, 2016; Lobel, 2016; Pelzer et al., 2019; Hughes, 2021). Rahman and Thelen's (2019) studied the US case and showed how certain institutional features also favour the impact of networks, already mentioned in section 4.1. They also stressed that the political power of platforms depends on their ability to build coalitions that legitimize their actions and thus bring a novel alliance between investors, managers and customers to the forefront. In doing so, this work also showed how platforms blur narratives and frames between some of the fundamental actors in the regulatory space.

Finally, the literature on cognitive frames has been less abundant. The above-mentioned studies tackle the problem of how these frames “provide legitimation and shape perceptions of institutions” as well as “shape perceptions of network structures.” Along these lines, Adler (2021) showed how, in the Boston debate about regulation, ride-hailing companies crafted and imposed a peculiar frame of "regulatory capture" in which regulators and government officials are portrayed as inclined to favour the taxi industry. There are also studies that focus on how frames shape perceptions about networks. For example, van Doorn et al. (2021) studied the campaigns that platforms deploy in civil society to avoid being regulated. Frames are thus critical to redefining the boundaries of the field, and who can legitimately participate in the regulatory debate.

In brief, the literature is gradually broadening and offering dynamic perspectives on the regulatory process, thus making it possible to overcome the fragmentation and narrowness of certain approaches that have emphasized the role of institutions, networks or frames while overlooking their interrelationships. A broader approach is key to understanding the regulatory developments that have dominated the agenda of platform work, especially since the pandemic, and which cannot be explained without an understanding of the complexities associated with the interrelationships between the three social structures.

Such an approach could offer a better way to explain contentious regulatory problems and recent controversies, such as the EU Platform Work Directive and lobbying by platform companies (Gig economy project, 2023) and the leaked evidence that Uber has broken laws, misled the police and illegally paid off politicians and policymakers (Davies et al., 2022). These examples show how corporate actors have infiltrated the state and institutions by using old and new techniques and by investing in media campaigns and technocratic advocacy to legitimize their actions both in institutions and in frames. To understand the big picture, one has to see the state as both a target of the change and an assemblage of institutions actively participating in the change. Ultimately, the change is due to a much more structural movement than the sort of movement that one-sided views of regulation could explain. There is consequently a need for critical enquiry into the scope and foundations of middle-range theories in industrial relations.

6. Concluding Remarks, Future Research and Limitations

I wished to explore which state and non-state actors have been identified as influential in shaping regulation of platform work, and which resources have enabled them to intervene. The study of platform work regulation has often fallen into one-sided approaches, although it has the potential to become a prolific space for broader approaches that emphasize the social processes that shape institutional change and the power resources of the main actors, both of which are radically redefining the context and contours of industrial relations.

More attention should be focused on the ongoing process of regulatory change, where institutions, networks and frames are the three structures that concurrently shape regulatory change and from which the actors obtain their resources to intervene in the process. In particular, more research is needed in at least three areas. First, there is a need for a more theoretical debate on the complex and even contradictory role of the state in regulating platform work. Such debate, which remains largely absent, may be key to understanding how new efforts of institutional experimentation coexist with systemic pressures for liberalization, with a shift of responsibilities to private actors, and with a growing tendency to judicialize labour disputes. Secondly, there is a need for research focused on a deeper exploration of platforms' network structure and their relationship to regulation and an understanding of the employment relationship as a legal category within these networks. While, as I have shown, there is research on the regulatory power of non-state actors and particularly platforms, there is still some nuance to be understood in this discussion. For example, if we recognise that the core of the business model is to articulate these multi-sided markets, it is worth asking when we are in the presence of an employment relationship and when we are not, and if so, what regulatory instruments could clearly distinguish which sector of platform employment should be regulated by either labour or private contract’s laws. Finally, there is a need to understand how frames guide the actions of those actors involved in enacting new laws or regulations on platforms, especially now with the enactment of new legal instruments in different countries. The content of such instruments, and the ability to enforce them, will depend on how the politics of regulation unfold.

This critical literature review certainly has limitations. First, as I indicated in the methodology section, it covers only the literature published in English. There may be many more debates on the subject of which I am unaware. Second, by taking a deductive approach, I have prioritized a discussion that stresses the roles of institutions, networks and frames and their interrelationships. There may be literature that has not been mentioned because it does not fit well enough with the proposed framework. Consequently, the primary aim of this review has been to offer a comprehensive analysis rather than an exhaustive one. These limitations may certainly be resolved in the future. Given the volume of production in this field, the present article reflects my ability to prepare a review that remains coherent and consistent in its entirety.

Appendices

Appendix

Literature reviewed

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful for the funding support provided by the Alliance MBS PhD Scholarship, which has been fundamental in moving my doctoral research forward. I would also like to extend my sincere appreciation to Miguel Martínez Lucio and Stephen Mustchin for their encouragement to publish this work and their always insightful feedback. Equally, I appreciate the constructive insights offered by Ioulia Bessa, Dalia Gesualdi-Fecteau, Debra Howcroft, Michael Francis, Adam McCarthy, and Mingwei Zhang, all of whom reviewed early versions of this work.

References

- Adams, A., Freedman, J., & Prassl, J. (2018). Rethinking legal taxonomies for the gig economy. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(3), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/gry006

- Adams, Z. (2023). Legal Mobilisations, Trade Unions and Radical Social Change: A Case Study of the IWGB. Industrial Law Journal, dwac031. https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwac031

- Adler, L. (2021). Framing disruption: How a regulatory capture frame legitimized the deregulation of Boston’s ride-for-hire industry. Socio-Economic Review, 19(4), 1421–1450. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab020

- Aloisi, A. (2022). Platform work in Europe: Lessons learned, legal developments and challenges ahead. European Labour Law Journal, 13(1), 4-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/20319525211062557

- Aloisi, A. (2016). Commoditized Workers: The Rising of On-Demand Work, A Case Study Research on a Set of Online Platforms and Apps. Comparative Labour Law and Policy Journal, 37(3), 653–690.

- Aloisi, A., & De Stefano, V. (2020). Regulation and the future of work: The employment relationship as an innovation facilitator. International Labour Review, 159(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12160

- Aslam, Y., & Woodcock, J. (2020). A History of Uber Organizing in the UK. South Atlantic Quarterly, 119(2), 412–421. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8177983

- Atkinson, J., & Dhorajiwala, H. (2021). The Future of Employment: Purposive Interpretation and the Role of Contract after Uber. The Modern Law Review, 1468-2230.12693. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12693

- Azzellini, D., Greer, I., & Umney, C. (2021). Why isn’t there an Uber for live music? The digitalisation of intermediaries and the limits of the platform economy. New Technology, Work and Employment, 37(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12213

- Azzellini, D., Greer, I., & Umney, C. (2022). Why platform capitalism is not the future of work. Work in the Global Economy, 2(2), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1332/273241721X16666858545489

- Beckert, J. (2010). How Do Fields Change? The Interrelations of Institutions, Networks, and Cognition in the Dynamics of Markets. Organization Studies, 31(5), 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840610372184

- Behrendt, C., & Nguyen, Q. A. (2018). Innovative Approaches for Ensuring Universal Social Protection for the Future of Work. ILO Future of Work Series; Research Paper 1.

- Berg, J., Rani, U., Furrer, M., Ellie, H., & Silberman, M. S. (2018). Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World. Geneva: ILO.

- Bessa, I., Joyce, S., Neumann, D., Stuart, M., Trappmann, V., & Umney, C. (2022). A global analysis of worker protest in digital labour platforms. International Labour Organization.

- Buendia Esteban, R. M. (2023). Examining recent initiatives to ensure labour rights for platform workers in the European Union to tackle the problem of domination. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 102425892211495. https://doi.org/10.1177/10242589221149506

- Cherry, M. A. (2020). A Global System of Work, A Global System of Regulation?: Crowdwork and Conflicts of Law. Tulane Law Review, 94(2), 184–245.

- Cherry, M. A. (2016). Beyond Misclassification: The Digital Transformation of Work. Comparative Labour Law and Policy Journal.

- Cherry, M. A., & Aloisi, A. (2017). ‘Dependent Contractors’ in the Gig Economy: A Comparative Approach. American University Law Review, 66(3), 635–689.

- Cohen, J. E. (2019). Between truth and power: The legal constructions of informational capitalism. Oxford University Press.

- Colvin, A. J. S. (2019). The Metastasization of Mandatory Arbitration. Chicago-Kent Law Review, 94(1), 3–24.

- Countouris, N. (2019). Defining and regulating work relations for the future of work. ILO.

- Cusumano, M. A., Gawer, A., & Yoffie, D. (2021). Can Self-Regulation Save Digital Platforms? Industrial and Corporate Change. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3900137

- Davidov, G. (2017). The Status of Uber Drivers: A Purposive Approach. Spanish Labour Law and Employment Relations Journal, 6(1–2), 6. https://doi.org/10.20318/sllerj.2017.3921

- Davies, H., Godley, S., Lawrence, F., Lewis, P., & O’Carroll, L. (2022, July 11). Uber broke laws, duped police and secretly lobbied governments, leak reveals. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2022/jul/10/uber-files-leak-reveals-global-lobbying-campaign

- De Stefano, V. (2016). The Rise of the ‘Just-in-Time Workforce’: On-Demand Work, Crowd Work and Labour Protection in the ‘Gig-Economy’. ILO Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 71.

- De Stefano, V. (2019). ‘Negotiating the Algorithm?’: Automation, Artificial Intelligence and Labour Protection. Comparative Labour Law and Policy Journal, 41(1), 15–46.

- De Stefano, V., & Wouters, M. (2019). Should Digital Labour Platforms Be Treated as Private Employment Agencies? European Trade Union Institute (ETUI); Foresight Brief.

- De Stefano, V., Durri, I., Stylogiannis, C., & Wouters, M. (2021). Platform work and the employment relationship. ILO Working Paper 27. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_777866.pdf

- Dubal, V. B., Collier, R. B., & Carter, C. L. (2018). Disrupting Regulation, Regulating Disruption: The Politics of Uber in the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), 919–937. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718001093

- Dukes, R. (2019). The Economic Sociology of Labour Law. Journal of Law and Society, 46(3), 396–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12168

- ETUI. (2020). Rethinking labour law in the digitalisation era. Conference report.

- Fligstein, N. (2001). Social Skill and the Theory of Fields. Sociological Theory, 19(2), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00132

- Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2011). Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01385.x

- Gall, G. (2020). Emerging forms of worker collectivism among the precariat: When will capital’s ‘gig’ be up? Capital & Class, 44(4), 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309816820906344

- Garben, S. (2019). The regulatory challenge of occupational safety and health in the online platform economy. International Social Security Review, 72(3), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/issr.12215

- Gawer, A. (2014). Bridging differing perspectives on technological platforms: Toward an integrative framework. Research Policy, 43(7), 1239–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.03.006

- Gig Economy Project. (2023, February 2). Defeat for the platform lobby: European Parliament backs stronger Platform Work Directive. Brave New Europe. https://braveneweurope.com/gig-economy-project-defeat-for-the-platform-lobby-european-parliament-backs-stronger-platform-work-directive

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Regulation of and by Platforms. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick, & T. Poell, The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 254–278). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473984066.n15

- Graham, M. (2020). Regulate, replicate, and resist – the conjunctural geographies of platform urbanism. Urban Geography, 41(3), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1717028

- Grimshaw, D. (2020). International organisations and the future of work: How new technologies and inequality shaped the narratives in 2019. Journal of Industrial Relations, 62(3), 477–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185620913129

- Hassel, A., & Sieker, F. (2022). The platform effect: How Amazon changed work in logistics in Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 095968012210824. https://doi.org/10.1177/09596801221082456

- Heeks, R. (2017). Decent Work and the Digital Gig Economy: A Developing Country Perspective on Employment Impacts and Standards in Online Outsourcing, Crowdwork, Etc. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3431033

- Helfen, M. (2015). Institutionalizing Precariousness? The Politics of Boundary Work in Legalizing Agency Work in Germany, 1949–2004. Organization Studies, 36(10), 1387–1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615585338

- Howcroft, D., & Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. (2019). A Typology of Crowdwork Platforms. Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018760136

- Hughes, R. C. (2021). Regulatory Entrepreneurship, Fair Competition, and Obeying the Law. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04932-y

- ILO. (2021). World Employment and Social Outlook 2021 the role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work. International Labor Office.

- Ilsøe, A. (2017). The digitalisation of service work – social partner responses in Denmark, Sweden and Germany. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 23(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258917702274

- Inversi, C., Dundon, T., & Buckley, L.-A. (2022). Work in the Gig-Economy: The Role of the State and Non-State Actors Ceding and Seizing Regulatory Space. Work, Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170221080387

- Inversi, C., Buckley, L. A., & Dundon, T. (2017). An analytical framework for employment regulation: Investigating the regulatory space. Employee Relations, 39(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-01-2016-0021

- Jaehrling, K., & Kalina, T. (2020). ‘Grey zones’ within dependent employment: Formal and informal forms of on-call work in Germany. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 26(4), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258920937960

- Johnston, H., & Land-Kazlauskas, C. (2019). Organizing On-Demand: Representation, Voice, and Collective Bargaining in the Gig Economy. ILO Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 94.

- Joyce, S., Stuart, M., & Forde, C. (2022). Theorising labour unrest and trade unionism in the platform economy. New Technology, Work and Employment, ntwe.12252. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12252

- Kapczynski, A. (2020). The Law of Informational Capitalism. Yale Law Journal, 129(5), 1460–1515.

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2018). Entrepreneurial Finance in the Era of Intelligent Tools and Digital Platforms: Implications and Consequences for Work. In Work and Welfare in the Digital Age: Facing the 4th Industrial Revolution (pp. 47–62).

- Kirchner, S., & Schüßler, E. (2020). Regulating the Sharing Economy: A Field Perspective. In I. Maurer, J. Mair, & A. Oberg (Eds.), Research in the Sociology of Organizations (pp. 215–236). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X20200000066010

- Kocher, E. (2022). Digital work platforms at the interface of labour law: Regulating market organisers. Hart.

- Koutsimpogiorgos, N., Slageren, J., Herrmann, A. M., & Frenken, K. (2020). Conceptualizing the Gig Economy and Its Regulatory Problems. Policy & Internet, 12(4), 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.237

- Lianos, I., Countouris, N., & De Stefano, V. (2019). Re-thinking the competition law/labour law interaction: Promoting a fairer labour market. European Labour Law Journal, 10(3), 291–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/2031952519872322

- Lobel, O. (2016). The Law of the Platform. Minnesota Law Review, 101(1), 87–166.

- Marchington, M. (Ed.). (2005). Fragmenting work: Blurring organizational boundaries and disordering hierarchies. Oxford University Press.

- Marenco, M., & Seidl, T. (2021). The discursive construction of digitalization: A comparative analysis of national discourses on the digital future of work. European Political Science Review, 13(3), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577392100014X

- Martínez Lucio, M., & MacKenzie, R. (2004). ‘Unstable boundaries?’ Evaluating the ‘new regulation’ within employment relations. Economy and Society, 33(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308514042000176748

- Martínez Lucio, M., Mustchin, S., Marino, S., Howcroft, D., & Smith, H. (2021). New technology, trade unions and the future: Not quite the end of organised labour. Revista Española de Sociología, 30(3), a68. https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2021.68

- Moyer-Lee, J., & Countouris, N. (2021). Taken for a ride: Litigating the digital platform model. ILAW Network. https://www.ilawnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Issue-Brief-TAKEN-FOR-A-RIDE-English.pdf

- Murray, G., Lévesque, C., Morgan, G., & Roby, N. (2020). Disruption and re-regulation in work and employment: From organisational to institutional experimentation. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 26(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258920919346

- Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M., & Choudary, S. P. (2016). Platform revolution: How networked markets are transforming the economy - and how to make them work for you. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Pelzer, P., Frenken, K., & Boon, W. (2019). Institutional entrepreneurship in the platform economy: How Uber tried (and failed) to change the Dutch taxi law. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 33, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.02.003

- Pesole, A., Brancati, M. C. U., Fernandez Macias, Biagi, F., & Gonzalez Vazquez. (2018). Platform workers in Europe: Evidence from the COLLEEM survey. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/742789

- Pollman, E., & Barry, J. M. (2016). Regulatory Entrepreneurship. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2741987

- Posner, E. A. (2021). How antitrust failed workers. Oxford University Press.

- Prassl, J., & Risak, M. (2016). Uber, Taskrabbit, and Co.: Platforms as Employers – Rethinking the Legal Analysis of Crowdwork. Comparative Labour Law and Policy Journal, 37(3), 619–651.

- Purcell, C., & Brook, P. (2022). At Least I’m My Own Boss! Explaining Consent, Coercion and Resistance in Platform Work. Work, Employment and Society, 36(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020952661

- Racabi, G. (2021). Effects of City–State Relations on Labor Relations: The Case of Uber. ILR Review, 74(5), 1155–1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939211036445

- Rahman, K. S. (2016). The Shape of Things to Come: The On-Demand Economy and the Normative Stakes of Regulating 21st-Century Capitalism. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 7(4), 652–663.

- Rahman, K. S., & Thelen, K. (2019). The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism. Politics & Society, 47(2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329219838932

- Rolf, S., O’Reilly, J., & Meryon, M. (2022). Towards privatized social and employment protections in the platform economy? Evidence from the UK courier sector. Research Policy, 51(5), 104492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104492

- Saunders, M. N. K., & Rojon, C. (2011). On the attributes of a critical literature review. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 4(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2011.596485

- Schüßler, E., Attwood-Charles, W., Kirchner, S., & Schor, J. B. (2021). Between mutuality, autonomy and domination: Rethinking digital platforms as contested relational structures. Socio-Economic Review, 19(4), 1217–1243. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab038

- Srnicek, N. (2017). The challenges of platform capitalism: Understanding the logic of a new business model. Juncture, 23(4), 254–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/newe.12023

- Stanford, J. (2017). The resurgence of gig work: Historical and theoretical perspectives. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 28(3), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304617724303

- Stewart, A., & Stanford, J. (2017). Regulating work in the gig economy: What are the options? The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 28(3), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304617722461

- Thelen, K. (2018). Regulating Uber: The Politics of the Platform Economy in Europe and the United States. Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), 938–953. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718001081

- Todolí-Signes, A. (2017a). The ‘gig economy’: Employee, self-employed or the need for a special employment regulation? Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 23(2), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258917701381

- Todolí-Signes, A. (2017b). The End of the Subordinate Worker? The On-Demand Economy, the Gig Economy, and the Need for Protection for Crowdworkers. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 33(Issue 2), 241–268. https://doi.org/10.54648/IJCL2017011

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

- Tubaro, P. (2021). Disembedded or Deeply Embedded? A Multi-Level Network Analysis of Online Labour Platforms. Sociology, 55(5), 927–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520986082

- Tucker, E. (2020). Towards a political economy of platform-mediated work. Studies in Political Economy, 101(3), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/07078552.2020.1848499

- Tzur, A. (2019). Uber Über regulation? Regulatory change following the emergence of new technologies in the taxi market. Regulation & Governance, 13(3), 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12170

- van Dijck, J. (2021). Seeing the forest for the trees: Visualizing platformization and its governance. New Media & Society, 23(9), 2801–2819. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820940293

- van Doorn, N., Ferrari, F., & Graham, M. (2022). Migration and Migrant Labour in the Gig Economy: An Intervention. Work, Employment and Society, 095001702210965. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170221096581

- van Doorn, N., Mos, E., & Bosma, J. (2021). Actually Existing Platformization. South Atlantic Quarterly, 120(4), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-9443280

- Vieira, T. (2021). The Unbearable Precarity of Pursuing Freedom: A Critical Overview of the Spanish ‘sí soy autónomo’ Movement. Sociological Research Online, 136078042110400. https://doi.org/10.1177/13607804211040090

- Wang, T., & Cooke, F. L. (2021). Internet Platform Employment in China: Legal Challenges and Implications for Gig Workers through the Lens of Court Decisions. Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 76(3), 541–564. https://doi.org/10.7202/1083612ar

- Weber, C. E., Okraku, M., Mair, J., & Maurer, I. (2021). Steering the transition from informal to formal service provision: Labor platforms in emerging-market countries. Socio-Economic Review, 19(4), 1315–1344. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab008

- Wood, A. J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., & Hjorth, I. (2019). Networked but Commodified: The (Dis)Embeddedness of Digital Labour in the Gig Economy. Sociology, 53(5), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519828906

- Wood, A. J., Martindale, N., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2021). Dynamics of contention in the gig economy: Rage against the platform, customer or state? New Technology, Work and Employment, ntwe.12216. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12216

- Woodcock, J., & Graham, M. (2020). The gig economy: A critical introduction. Polity.

- Zhang, C. (2019). China’s new regulatory regime tailored for the sharing economy: The case of Uber under Chinese local government regulation in comparison to the EU, US, and the UK. Computer Law & Security Review, 35(4), 462–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2019.03.004

- Zou, M. (2017). The Regulatory Challenges of Uberization in China: Classifying Ride-hailing Drivers. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2866874

List of figures

Figure 1

Reciprocal Influences of the Three Structures in Market Fields

Figure 2

Data Collection

10.7202/1083612ar

10.7202/1083612ar