Abstracts

Abstract

Over the past several decades, industrial relations (IR) scholars have consistently advocated for better integration of their conflict theory and empirical research with that of the neighbouring discipline of organizational behaviour (OB). Achievement of such a goal has nonetheless been a continuing challenge. Offering a novel perspective on the quest for integration, this paper categorizes the distinct and dissimilar conceptual norms of conflict in IR and OB, concluding that conceptualizations of conflict in the two disciplines are built upon irreconcilable logics. Although a unified conceptualization of conflict across these differing logics is not possible, a better understanding of their irreconcilability could facilitate a more robust and ultimately fruitful dialogue among IR and OB researchers.

Summary

Over the past several decades, industrial relations (IR) scholars have consistently advocated for better integration of their theory and empirical research on conflict with that of the neighbouring discipline of organizational behaviour (OB). Achievement of such a goal has nonetheless been a continuing challenge.

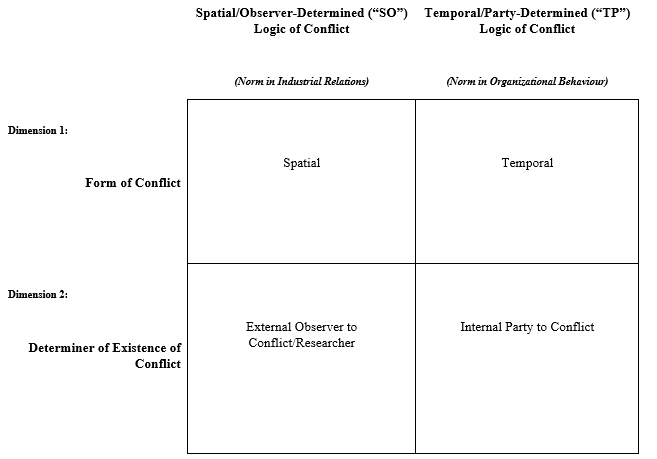

Offering a novel perspective on the quest for integration, this paper categorizes the distinct and dissimilar conceptual norms of conflict in IR and OB. Conflict is normally spatial in IR and temporal in OB. In IR, the existence of conflict is commonly determined by the observer (i.e., the researchers). In OB, it is determined by the observed (i.e., the parties in the workplace, be they individuals, teams or organizations).

This paper argues that conceptual norms of conflict in IR and OB are built upon distinct, irreconcilable logics. The norm in IR is labelled a Spatial/Observer-determined (SO) logic, while the norm in OB is labelled a Temporal/Party-determined (TP) logic. The SO logic conceptualizes conflict spatially as a situation or state of affairs that can be determined by a researcher or other observer. Conflict itself is conceptualized as existing spatially among opposing interests, objectives or values. Alternatively, the norm in OB research is to utilize a TP logic that conceptualizes conflict as a temporal process between or among opposing parties, who determine when it begins and ends. Although a unified conceptualization of conflict across these differing logics is not possible, a better understanding of their irreconcilability could facilitate a more robust and ultimately fruitful dialogue among IR and OB researchers.

Keywords:

- organizational theory,

- industrial relations theory,

- organizational behaviour,

- organizational conflict

Article body

1. Introduction

The past several decades of industrial relations (IR) scholarship on conflict have seen continued calls for wider integration of theory and empirical research in IR with that of the neighbouring discipline of organizational behaviour (OB). Writing in the mid-1970s, Strauss (1977: 329) described his dismay that Walton and McKersie’s (1965) A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations—which Strauss deemed to be “the first major attempt to integrate organizational behavior and industrial relations approaches to conflict”—would “stand in lonely isolation” in the decade following its publication. Notwithstanding this disappointment, Strauss (1977: 337) ended his paper with cautious optimism that an “interdisciplinary theory of conflict and conflict resolution” could still develop and “provide a renewed link between IR and OB.”

A recent flurry of calls from IR scholars for better integration of conflict theory and research with OB indicates that Strauss’s hope has not yet been realized. Avgar and Colvin (2017: 3–4) in an historical overview of research on workplace conflict in IR and OB explained that although some “scholars view conflict as a dynamic process made up of specific conflict episodes,” others “view conflict as a group level climate measure capturing employee perceptions,” and “[s]till others view conflict as objective manifestations of labor-management relations captured by concrete events.” The first two definitional categories represent norms in the OB literature, while the last one represents the common perspective on industrial conflict in IR. These definitional differences are frequently obscured when, as Mikkelsen and Clegg (2019: 167) have argued, scholars throughout the organizational sciences operate with a “tacit assumption that we all know—and all agree on—what conflict is.” For example, in a recent special issue of the Industrial and Labor Relations Review dedicated to papers on “conflict and its resolution in the changing world of work,” the authors of only one (Budd et al., 2020) of the issue’s thirteen articles included a definition of conflict (Katz, 2020).

There is still lack of agreement on what exactly conflict is, but this lack has not extinguished hope for more integration of conflict theory and research in IR and OB. Budd (2020: 80) recently argued that conflict is a construct that could benefit from interdisciplinary engagement and conversation between IR’s institutional approach and OB’s behavioural orientation. Relatedly, Kochan, Riordan, Kowalski, Khan and Yang (2019) highlighted the potential for stronger integration of IR and OB research on forms of collective conflict. In a paper dedicated to the topic of integration, Avgar (2020: 283) argued that Kochan, Katz and McKersie’s (1986) strategic choice framework for the analysis of industrial relations actors’ choices, could provide the theoretical scaffolding for a new “conflict integration framework… a tool to make sense of existing conflict research and to identify avenues for future conceptual and empirical work” in IR, OB and law. After reviewing the state of conflict research in all three disciplines, Avgar (2020: 283) concluded that their respective “insights should serve as building blocks for a more comprehensive and integrated understanding of conflict and how it is managed within organizations.” To Avgar, integrating conflict research across disciplines will make the resulting whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Although the above-mentioned papers all exude optimism, they also acknowledge barriers to successful integration. For instance, IR and OB usually work with differing levels of analysis in conflict research. From an IR perspective, Avgar and Colvin (2017), Kochan et al. (2019) and Avgar (2020) point out that OB research almost exclusively focuses on workgroup conflict at the micro- or meso-levels, while IR research frequently focuses on macro-level policies and systems for managing conflict. This view is supported by recent papers on the state of conflict theory and research in OB (Bendersky et al., 2014; Contu, 2019; Mikkelsen and Clegg, 2018; Mikkelsen and Clegg, 2019). Relatedly, another challenge to integration has come from the differing assumptions of IR and OB on the inevitability of conflict in the employment relationship. Considering the three definitional categories of workplace conflict offered by Avgar and Colvin (2017) discussed above, one can see that the contemporary norm in OB uses definitions of conflict that are subjective and thus make conflict not inevitable. In IR, conflict is commonly understood to be inherent to the employee-employer relationship and therefore inevitable. Budd (2020: 79–80) found that this inevitability of conflict is a “more fundamental” distinction than others, arguing that it makes interdisciplinary conversations a “tough sell.” Avgar (2020: 307) would agree that the above-mentioned challenges “help explain the absence of sufficient disciplinary integration,” yet he remained undeterred from pursuing an integrative project, arguing that “these barriers should not obscure the overarching goal of better describing and explaining the manifestation of conflict within organizations.”

Could an alternative approach to advance a conversation between IR and OB about their differing conceptualizations of conflict be more fruitful than prior attempts? This paper’s answer is yes. If conflict scholars in IR and OB were to apprehend and then fully consider the ramifications of the differing underlying logics of conflict in both disciplines, they would conclude that the integration quest has to date been focused on the wrong things. In contrast to past attempts that have considered distinctions between IR and OB conflict scholarship primarily via examination of the level of analysis (e.g., Avgar, 2020; Kochan et al., 2019) or the frame of reference for viewing the inevitability of conflict in the employment relationship (e.g., Budd, 2020; Godard, 2014), this paper offers a different approach, one that compares norms for conceptualization of conflict in the two disciplines. It does so by shining light on two key dimensions that have remained hidden in the integration conversation to date. The first dimension assesses the form in which conflict is conceptualized, while the second one considers how conflict is determined to exist. Dissimilarities between IR and OB on each dimension represent contrasting logics of conflict and illuminate the differing norms operating in the two disciplines.

Although I deem these logics to be irreconcilable, they can help us better understand why past attempts at increasing the level of interdisciplinary conversation and collaboration have had a hard time getting off the ground. IR and OB each conceptualize conflict with fundamentally different bases in logic. This understanding does not condemn the two disciplines to remain hopelessly apart, though. Instead, it provides IR and OB scholars a valuable new opportunity to reorient and recalibrate their conversations with each other.

2. Dimension One: The Form of Conflict

Form is the first conceptual dimension of conflict contributing to different logics in IR and OB. Conflict is commonly spatial in IR and temporal in OB.

2.1 IR: Conflict as Spatial

Conflict has a long history of being viewed in spatial terms by industrial relations scholarship. An instructive example is provided by Chamberlain (1944: 367–368), who clearly sees cooperation and conflict as opposing concepts:

If an orderly process of industrial collaboration is to be established, the areas of cooperation between the employer and the union must be enlarged at the expense of the areas of conflict. The trade agreement embodies the area of cooperation accepted by both parties for a prescribed period of time.

Chamberlain considers conflict to be the baseline state of affairs in the employment relationship, unless, importantly, matters are moved from the realm of conflict into the realm of cooperation through their inclusion in a collective bargaining agreement. Chamberlain’s “areas of conflict” therefore are seen to be conceptualized spatially. A related spatially-oriented concept is the classic IR example of the collective bargaining “contract zone,” which Farber and Katz (1979: 55) defined as the “range of potential settlements both parties consider preferable to a potential strike.” Traditionally in IR, contract zones for specific management and union parties are construed in spatial terms, as such zones are theorized to be based on assessments of the underlying situation (i.e., the economic environment in which firms and unions find themselves).

Kochan (1998: 37) argued that “[i]ndustrial relations theory starts from an assumption that an enduring conflict of interests exists between workers and employers in employment relationships” and that this is “the primary feature that distinguishes the field from its counterparts.” Kochan’s perspective, as expressed here, is based on the assumption that conflict has a spatial form. The “enduring conflict of interests” he discusses aligns with the “pluralist” frame of reference as well as the “radical” (i.e., “critical”) frame of reference developed by Fox (1974) to categorize distinct orientations and understandings of the employment relationship. In Fox’s framework, the pluralist and critical frames of reference exist alongside a third frame: the “unitary” (i.e., “unitarist”) frame of reference (Budd and Bhave, 2019). The frames of reference are commonly understood within IR as a meta-theoretical orientation regarding conflict in the employment relationship (Tapia et al., 2015). With its emphasis on class conflict, a critical frame of reference would view conflict between labour and capital—i.e., employees and employers—as ubiquitous and pervasive. A unitarist frame of reference would lead to the opposite view. The employment relationship in this frame is considered to be inherently one of cooperation that is not characterized by conflicting interests. Instead, the interests of employees and employers are seen to interlink and enable all to work together to achieve shared goals. Lastly, a pluralist frame of reference, which animates most contemporary industrial relations scholarship, represents a middle ground between the radical and unitarist frames (Budd and Bhave, 2019; Heery, 2016).

Upon closer examination, one can see that Fox’s (1974) frames of reference are constructed using a spatial form of conflict. Each frame of reference occupies a varying amount of conflict territory in the employment relationship. Chamberlain (1944) can be seen to be operating from a pluralist frame of reference, in which “areas of conflict” can be converted into “areas of cooperation” through collective bargaining. Alternatively, a scholar utilizing a critical frame of reference would view Chamberlain’s “areas of conflict” as being irreducible. Within the critical frame, conflict would encompass the entire territory on the conceptual map of the employment relationship, whether or not a collective bargaining agreement is in effect. From the opposite perspective, within the unitarist frame, conflict would encompass little to none of the same territory. Conflict would not be seen as inherent, since the employment relationship is instead considered to be characterized by cooperation and aligned interests (Budd and Bhave, 2019). Although each frame of reference can be seen to take a differing stance regarding the breadth of conflict’s theoretical territory, Fox’s frames of reference concept itself considers conflict to be ultimately between the interests or goals of employees and those of employers. Interests, goals or objectives, though connected to parties, are understood to be distinct from the parties themselves. If conflict is conceptualized spatially, it is the interests or goals of parties that are actually considered to be in conflict. For example, take the statement that a worker, Janet, has interests that conflict with those of her supervisor, Gina. Such a statement is conceptually distinct from the one in which Janet is in conflict with Gina.

2.2 OB: Conflict as Temporal

The temporal form of conflict used in OB can be contrasted with the spatial form commonly found in IR. In a widely-cited chapter, De Dreu and Gelfand (2008: 36) provided a representative definition of conflict used in contemporary OB, writing that “conflict is clearly a dynamic phenomenon that unfolds over time.” Earlier in the chapter, De Dreu and Gelfand (2008: 6) fully defined conflict as “a process that begins when an individual or group perceives differences and opposition between oneself and another individual or group about interests and resources, beliefs, values, or practices that matter to them.” Although De Dreu and Gelfand found their broad definition to be commonly utilized in OB, they acknowledged that its usage is often implicit. The definition functions behind the scenes of conflict in specific settings, such as workgroup conflict, which is almost always measured using Jehn’s (1995, 1997) “task,” “relationship,” and “process” conflict categorization. Jehn’s tripartite categorization has been found to be the most common way conflict is referred to in OB research (Nieto-Guerrero et al., 2019; O’Neill and McLarnon, 2018).

The temporal form of conflict norm in OB can be traced back to research from the late 1960s that attempted to make sense of the rapidly expanding and increasingly disparate organizational conflict literature of the day. In an influential paper, Pondy (1967) argued that organizational conflict should be thought of as a “dynamic process” because elements used in previous scholarship to define conflict could all fit within that arguably global conceptualization. Pondy (1967: 319) concluded:

The term conflict refers neither to its antecedent conditions, nor individual awareness of it, nor certain affective states, nor its overt manifestations, nor its residues of feeling, precedent, or structure, but to all of these taken together as the history of a conflict episode.

Pondy’s conceptualization of conflict served as a launching pad for Thomas’s (1976, 1992) subsequent influential theorizing in OB. Surveying the literature, Thomas (1976: 892) argued that OB scholars have used two distinct approaches to understand “conflict behavior.” He identified a “process model” as one approach and a “structural model” as the other. In process model research, “the objective is commonly to identify the events within an episode and to trace the effect of each event upon succeeding events.” Alternatively, Thomas (1976: 893) categorized research to fall within his structural model if it has a goal of “identify[ing] parameters that influence conflict behavior.” It can be argued that Thomas’s (1976: 912) process model gives more explanatory power to factors within a particular conflict episode under examination, while a structural model focuses on causes of conflict behaviour that come from external “pressures and constraints,” which would include social and economic causes.

Although at first glance Thomas may seem to have made space for a spatial form of conflict in his structural model, upon closer examination one can see that he actually maintains a temporal form of conflict within it. By framing the overall project of organizational conflict research in terms of explaining and understanding “conflict behaviour” (by using a process model, a structural one or elements of both), Thomas, following Pondy, conceptualized conflict as episodic and therefore in temporal terms. In Thomas’s process model, conflict behaviour is attributed to an inward focus that is centred primarily on past events. In his structural model, it is attributed to an outward focus on conditions or forces theorized to influence party behaviour. Both models always aim to explain the causes of conflict behaviour within conflict episodes. Rather than differing over form, the two models upon closer investigation simply differ over where they are searching for the cause of such behaviour.

Additionally, and unlike a spatial form of conflict, the temporal form of conflict used in OB views parties (i.e., individuals, groups, organizations, etc.) as being directly in conflict with each other. This may be seen in De Dreu and Gelfand’s (2008: 6)though (p. 6-7 definition discussed previously. Even though opposed “interests and resources, beliefs, values, or practices” are provided as the reasons for party perceptions, conflict is ultimately determined in line with De Dreu and Gelfand’s definition: it “begi[ns] when an individual or group perceives differences and opposition between oneself and another individual or group.” One can see that this temporal form, with its attendant starting point of conflict based (at a minimum) on the perceptions held by one party, considers the parties as being directly in conflict, instead of their interests, values or practices, to be what ultimately are in conflict. A close reading shows that this form of conflict does not permit our hypothetical worker Janet’s interests to be in conflict with her supervisor Gina’s interests. Instead, Janet is in conflict with Gina, since the initiation of the process of conflict happens only through the perceptions held by either party or both.

3. Dimension Two: The Determiner of Conflict

A second dimension contributes to the differing logics of conflict in industrial relations and organizational behaviour. It concerns how the existence of conflict is determined. In IR, the existence of conflict is normally determined by observers (i.e., researchers). In OB, it is determined by the observed (i.e., parties—be they individuals, teams or organizations).

3.1 IR: Conflict Determined by an External Observer

To further consider the logic underlying De Dreu and Gelfand’s (2008: 6)though (p. 6-7 definition from OB, it will be helpful to contrast it with a recent definition of conflict by IR scholars Budd, Colvin and Pohler (2020: 256) who defined conflict “as an apparent or latent opposition between two or more parties that results from differences that are either real or imagined.” In this formulation, conflict as an “apparent or latent opposition” resulting from “differences” is not temporal in form. According to this definition, conflict exists (or does not) irrespectively of any particular or potential behaviour and thus can ultimately be seen to be conceptualized spatially rather than episodically. This definition does not require knowing the perceptions held by the parties to determine the existence of conflict. It does not directly state who or what determines whether an “apparent or latent opposition” exists. Scholars operating with such a conceptualization accordingly retain the ability to determine if conflict exists in a particular situation and is reflected in party behaviour. Such determination of the existence of conflict also can be seen to be linked to norms of what constitutes valid empirical evidence. Kochan (1998: 39) points out that IR scholars utilizing a critical frame of reference commonly lack trust in worker perceptions, since such perceptions are deemed to reflect “individual false consciousness shaped by the authority and control structures under which people work.” He goes on to say that pluralists, for their part, do not fully dismiss the utility of worker perceptual data, yet can “share some of the skepticism” of researchers in the critical camp.

3.2 OB: Conflict Determined by Involved Parties

In OB conflict research, the existence of conflict depends fully on the perceptions held by the parties (i.e., individuals or groups) in the workplace. Task conflict, relationship conflict, and process conflict, for example, are present only if workgroup members say so on survey items (e.g., Jehn, 1997; Jehn et al., 2008). From an IR perspective, such perceptions would likely immediately appear to be clouded, as they could lead workers to perceive opposition with coworkers as task conflict or relationship conflict, while not perceiving opposition between front-line employees of a manufacturing firm and the firm’s “unseen” board of directors, for instance. In the alternative IR norm, conflict would be conceptualized as being present in a situation in which workers were productively at work inside a factory just as it would be present if workers at the same factory were instead out on the picket line. OB scholars could respond to IR researchers by arguing that the perceptions held by the parties should not be discounted, as it would be presumptuous for IR researchers to make conclusions about the existence of conflict independently, without consideration of the perspectives of the involved parties (Hartley, 1988: 58). Within the OB conceptual norm, conflict would not exist until parties in the workplace perceived it.

3.3 Example of a Logical Mismatch: Determination of Conflict

If scholars fail to acknowledge that they differ in their conceptual assumptions about the determiner of the existence of conflict, they may end up speaking past each other. An example can be found in the recent integrative theory-building paper of Budd et al. (2020), whose definition of conflict was introduced earlier. Budd et al. (2020: 255) proffer a new framework that aims to be relevant to social science disciplines that study conflict. They aim to be more comprehensive than past discipline-centred efforts in identifying and incorporating “the full range of sources of conflict.” Explaining further, Budd et al. (2020: 256) write:

An explicit, integrated framework, however, is important to educate new dispute resolution professionals and quicken their learning curves, assist managers and others who lack training or experience, and promote reflection among experienced professionals. Such a framework can also provide new insights for academic research, encouraging greater cross-disciplinary pollination of ideas and approaches to studying conflict.

Although Budd et al. (2020: 255) point out that the disciplines they discuss offer varied “approaches to studying conflict” that examine “particular types or sources of conflict,” the authors do not consider the possibility that conflict itself may be conceptualized differently across those disciplines. Their phrasing in all of the above-cited passages indicates that they see the disciplines as studying “particular types or sources” of the same thing—conflict—even if they find that the disciplines are doing so in differing ways.

Not only has there been no commonly shared view among the social sciences of what is covered by “sources of conflicts,” as Budd et al. (2020) averred, there has been, and continues to be, no one shared conceptualization of conflict itself. In terms of the determination of conflict existence, all three of Budd et al.’s (2020) sources of conflict categories rely on the assumption that conflict can be determined by outside observers. Conflict thus does not depend on an involved party to exist using this logic. For example, when they described a third category of sources of conflict, i.e., “psychogenic sources of conflict,” Budd et al. (2020: 264) wrote that “…conflict may not manifest itself if an individual does not perceive a situation, process, or outcome as threatening enough to his or her well-being or quality of life to elicit an emotional reaction.” Since conflict is assumed to potentially exist in a latent form beyond party perception , the phrasing shows that the authors consider its existence not to be dependent on such perceptions. Alternatively, if the definition of conflict comes from OB, such as Jehn’s (1995)—which aligns with the party-determined norm found in OB on this dimension, the perceptions held by involved parties would now become central. Conflict, as defined as “perceptions by the parties involved that they hold discrepant views or have interpersonal incompatibilities” would be determined completely and fully by the parties’ views (Jehn, 1995: 257). If one were to proceed with this definition, it would be nonsensical to claim that conflict could exist in an unmanifested form, since it would not exist in any form or fashion beyond the perceptions held by the involved parties.

4. Logics of Conflict in Industrial Relations and Organizational Behaviour

The previous two sections introduced two foundational dimensions of conflict, which are combined and displayed graphically below. By cross-tabulating the form of conflict with access to its knowability, we can visualize the two distinct logics of conflict in industrial relations and organizational behaviour.

Figure 1

Logics of Conflict in Industrial Relations and Organizational Behaviour

Figure 1 helps make sense of the distinct conceptual norms for conflict in IR and OB. The norm in IR is Spatial/Observer-determined (SO) logic, while the norm in OB is Temporal/Party-determined (TP) logic. Much of the continuing disconnect between IR and OB conflict research can be attributed to a lack of adequate translation across the logics. The SO logic conceptualizes conflict spatially as a situation or state of affairs that can be determined by a researcher or other observer. Conflict itself is conceptualized as existing spatially among opposing interests, objectives or values. Alternatively, a TP logic conceptualizes conflict as a temporal process between or among opposing parties; it is thus determined to begin and end by the same parties. What insight can be gleaned from the logics of conflict outlined in Figure 1? In the remainder of this section, I will offer some initial answers to this question by first elucidating a few ways that the logics can add to recent analyses of the conceptualization of conflict within OB. Next, I will use the logics to explore the issue of why Fox’s (1974) frames of reference, though widely admired and used in IR, are rarely mentioned or acknowledged in OB. Last, I will conclude with a discussion of the logical confusion that can seemingly result when IR and OB scholars attach the term “conflict” to certain behaviours, thereby obscuring the underlying logic present.

Within OB, the two logics in Figure 1 can add an additional perspective to Contu’s (2019) and Mikkelsen and Clegg’s (2019) recent commentaries that address the theorization of conflict in their discipline and which encourage critical thinking about the concept. For her part, Contu (2019: 1450) pushed back against a “sanitized” conceptualization of conflict in OB “that is transformed into a benign force to be kept within specific limits (in themselves unclear).” Contu’s argument aligns with Mikkelsen and Clegg’s (2019: 172) finding that conflict in OB has often been considered to be an “instrumental means” for organizational management to use effectively. Mikkelsen and Clegg (2019: 173) argued that this instrumental view of conflict has not sufficiently encouraged a research agenda on outcomes of conflict beyond those of productivity and performance. It would be more helpful to analyze the logic of conflict in OB from a comparative perspective. The temporal logic of conflict in OB, for example, appears to direct scholarship and practice to “the conflict episode,” which subsequently channels analytical attention toward management of each party’s perceptions, instead of channeling it toward the broader landscape or situation that would be relevant if conflict were to be considered spatially. Thus, this contrast in logic could provide a new explanation for why OB conflict research has not regularly utilized the broader, more wide-ranging outcomes that interest Mikkelsen and Clegg (2019: 173).

By comparing spatial/observer-determined logic and temporal/party-determined logic, we can also better understand why OB has not taken up the concept of frames of reference (Tapia et al., 2015). As discussed earlier, that concept requires an assumption that conflict has a spatial form. According to Fox (1974), conflict occupies different amounts of terrain in the employment relationship, depending on whether one sees that relationship from a unitarist, pluralist or critical frame of reference. According to Cutcher-Gershenfeld (1991: 242), when speaking about IR, frames of reference are in most cases applied implicitly by observers and analysts. A specific frame of reference permits a researcher to see conflict according to the assumptions of that frame and therefore fits within the SO logic of conflict. Using a TP logic of conflict, on the other hand, one would not find the same sort of alignment. Since parties in organizations hold the key to the existence of conflict in a TP logic, a researcher utilizing such a logic of organizational conflict need not explicitly or implicitly engage with any frame of reference because conflict as an episodic process is conceptualized only if the parties perceive it. If a TP logic of conflict is conceptualized temporally and determined by the parties’ perceptions, it will not create the conceptual space for spatially-oriented conflicts of interest to exist. Within a TP logic, interests can be attributed to specific parties, who remain ontologically distinct.

If one considers the unitarist frame of reference in light of the above discussion, one can further understand why integration of IR and OB conflict scholarship has been a perennial challenge. Compare a hypothetical exchange between IR scholars Frangi, Noh and Hebdon (2018) and OB scholars Bradley, Anderson, Bauer and Klotz (2015). Frangi, Noh and Hebdon (2018: 285–286) argued that the unitarist frame of reference is the norm in OB: “The unitarist sees conflict as dysfunctional, with order and harmony being the natural state of affairs.” Yet when Bradley and colleagues (2015: 243) reviewed the OB literature, they identified “evidence for beneficial conflict.” In particular, they found three situations in which past research had shown that task conflict within teams is beneficial to team performance: “when tasks are sufficiently complex, when conditions are in place that enhance the ability of the team to process information, or when conflict is expressed in an appropriate manner when it emerges” (Bradley et al., 2015: 266). Frangi, Noh and Hebdon did not appear to consider task conflict in terms of TP logic when they argued that OB scholars see conflict as “dysfunctional.” IR researchers like themselves conceptualize conflict in terms of SO logic and thus fail to understand that OB scholars operating from a TP logic would not conceptualize conflict in the same way. Moreover, OB scholars Bradley and colleagues could claim that Frangi, Noh and Hebdon were wrong to characterize their position as a “unitarist” perspective on conflict. Since Bradley and colleagues were operating from a TP logic and making a “pro-conflict” argument, they likely did not consider how proceeding uncritically with a conceptualization of conflict based on a TP logic forecloses engagement with IR, whose meta-theory of the employment relationship is built on an alternative logic of conflict.

Last, both IR and OB researchers frequently refer to certain behaviour as conflict, thus obscuring key differences in the underlying conceptual logics they use. For example, imagine an interpersonal dispute between co-workers over the optimal temperature of their shared office as well as a formal gender discrimination grievance filed by an employee. Each hypothetical example could easily be labeled “conflict behaviour” by IR and OB scholars. Therefore, it is essential to analyze specific discursive conventions used by researchers as they discuss conflict behaviour to identify the underlying logic being utilized. In IR, scholars often use the phrases “expressions of conflict” or “manifestations of conflict” to distinguish conflictual behaviour from conflict itself. Batstone (1979: 71) discussed “expressions of conflict outside of institutionalized channels” in his analysis of organizational conflict, and Avgar (2020: 298) referred to “concrete manifestations of conflict” in his recent paper, discussed earlier. In Batstone’s and Avgar’s respective phrasing, conflict conceptually maintains its spatial form even though it may be “expressed” or “manifested” through certain actions. Importantly, conflict expression or manifestation is not required for conflict to be still deemed in existence under an SO logic (Gall and Hebdon, 2008). In Batstone’s and Avgar’s conceptualizations, conflict is akin to oxygen—invisible, yet always present in the workplace (albeit at different levels and concentrations). Conflict, conceptualized in this manner, “is an organizing principle and not just a form of behaviour” (Edwards, 1992: 394). Due to an assumption of a spatial form, conflict exists beyond behaviour within the IR norm. This stands in contrast to the TP logic of conflict in OB research. Although Pondy (1967: 298) attempted to incorporate “antecedent conditions of conflictual behavior” into his process view of conflict, the conceptualization of conflict offered by IR scholars Batstone, Avgar and Edwards is oriented spatially—leading to a logical disconnect. The concept of “latent conflict” introduced by Pondy (1967: 300), representing the above-mentioned “antecedent conditions,” is theorized in his process view to represent “underlying sources of organizational conflict” and is considered to be the first stage of a “conflict episode.” But by making latent conflict a stage of a conflict episode, Pondy attempted to represent temporally a concept that the alternative SO logic would conceptualize spatially. Conflict according to that logic would not be considered to end when the next stage of Pondy’s model begins, but instead could only be reduced or eliminated spatially (e.g., by enlarging Chamberlain’s (1944) “area of cooperation”).

5. Considering Logics of Conflict in IR and OB: Implications and Future Directions

The logics of conflict identified in this paper aim to provide new tools for answering the question: why have past attempts failed to integrate the conflict theory and research of industrial relations with that of organizational behaviour? Differing logics of conflict have been a hidden contributing reason, even in the face of increasing willingness from conflict scholars in IR and OB to construct new and deeper intellectual bonds. Seeing the potential for more interdisciplinary conflict theory and research in IR and OB, Avgar (2020: 307) encouraged his readers not to lose sight of what he believed to be the “overarching goal of better describing and explaining the manifestation of conflict within organizations,” a goal shared by both disciplines. As in the Budd et al. (2020) paper discussed earlier, Avgar’s phrasing— “better describing and explaining the manifestation of conflict”—likewise assumes that there is one ”conflict” to be better described and explained. My explication of the distinct SO and TP logics of conflict norms in IR and OB has shown this not to be the case.

Before integration attempts can succeed, IR and OB scholars must first gain awareness of their own operating logic of conflict. Only then will they become able to consider an alternative one. For OB scholars, awareness of the SO logic can facilitate deeper understanding of the animating conceptions of conflict in IR that hopefully will make IR approaches seem less foreign. Such an understanding would enhance current conversations within OB about the accuracy and appropriateness of the discipline’s methods for measuring task, relationship and process conflict (e.g., Bendersky et al., 2014; DeChurch et al., 2013; Park et al., 2020; Weingart et al., 2015).

For IR scholars, the logics will assist in three key ways. First, the introduction of the SO and TP conceptual logics can help IR go beyond past attempts to understand the lack of integration of conflict scholarship with OB and other neighbouring disciplines by using levels of analysis (e.g., Avgar, 2020; Kochan et al., 2019) and frames of reference (e.g., Budd, 2020; Godard, 2014). The conflict logics offered herein will enable IR scholars to see the logical flaws of these approaches to the integration discussion and can provide an alternative paradigm for an IR-OB conversation on conflict to proceed.

Second, a new awareness of the way conflict is assumed to be determined (Dimension 2) will advance the ongoing dialogue within IR on whether the perceptions held by the opposing parties could be better and more broadly incorporated into the discipline’s conceptual norms. Bray, Budd and Macneil (2020: 136) advocated for such a perspective in a recent paper, calling for IR to consider “mental models” of employees and managers “to complement the traditional focus on material practices” in IR theorizing. The two logics of conflict introduced in this paper not only provide new tools to understand how IR and OB researchers conceptualize conflict but also widen the conversation toward a better understanding of how individual employees and managers conceptualize conflict as well. A study by Avgar and Neuman (2015) on “conflict accuracy” in an OB-oriented journal is instructive. Employees of a U.S. state government scientific agency were asked “to report whether they believed members of their team— including themselves—were in conflict” (Avgar and Neuman, 2015: 72). Because the study measured task and relationship conflict, its conflict logic can be properly categorized as TP. Imagine, though, the case of a hypothetical study participant (“Alan”) who is one of six team members (including one supervisor). Assume that Alan personally operates with an SO logic of conflict and a critical frame of reference. In this case, Alan could easily still “see” (and therefore “inaccurately” report, according to a researcher operating with a TP logic) ongoing conflict between himself and his supervisor without any requisite feelings of “interpersonal incompatibilities” or “disagreements about work,” which are key definitional components of relationship and task conflict respectively (Avgar and Neuman, 2015: 73). Since Avgar and Newman’s study defines “conflict accuracy” in terms of how well an employee’s perception aligns with those of others on her team, the study’s conclusions do not consider the role of study participants’ own logics of conflict in how the participants experience and report conflict.

Third, the conceptual logics of conflict introduced in this paper bring needed clarity to ongoing discussions on the place of conflict in IR theory more generally—outside the OB integration conversation. In a recent paper, Riordan and Kowalski (2021: 582) argued that empirical developments, such as new forms of work and a blurring of economic and social identities, have created a “need to update IR’s accounting of conflict, a construct that has been central to the field since its inception” with two new concepts: “multiplicity, or the presence of new and varied actors with diverse goals, and distance, or the growing gap between those who control work and those who labor, induced by a variety of organizational forms, practices, and rules.” By not focusing on the internal logic of conflict as conceptualized historically in IR theory and instead arguing that external empirical conditions should be the motivator for changes to IR’s theorization of conflict, Riordan and Kowalski (2021: 591) missed several logical disconnects of such an approach—notably by 1) referring to the traditional IR model of conflict in both spatial and temporal terms—and 2) ultimately advocating for IR to adopt a TP logic, which would represent a major logical transformation of the IR norm. Alternatively, I posit that conflict cannot be observed, deduced or inferred directly from empirical evidence because a certain conceptualization of conflict is always brought to—and therefore shapes—any analysis of empirical evidence that is claimed to represent or indicate conflict. The conflict logics that I elucidate challenge the belief that empirical developments in the realm of conflict at and around work require concomitant conceptual development (Avgar, 2020; Budd et al., 2020; Riordan and Kowalski, 2021).

By becoming aware of the SO and TP conflict logics, IR and OB scholars will have a new opportunity to reflect on the ways in which they take implicit conceptual stances on conflict in their theorizing and their empirical research. As a result, IR and OB scholars will also be better able to understand why their disciplines each teach and train students and practitioners very differently under the same banner of “conflict management.” As an example, consider, Katz, Kochan, and Colvin (2017: 292–327) in their introductory IR textbook chapter on the topic. The authors first covered grievance procedures and labour arbitration in collective bargaining agreements and then moved to such topics as nonunion grievance procedures, the ombudsman function and the role of employment law. In contrast, Alblas and Wijsman (2021: 383) in their introductory OB text, first elucidated the “several possible forms of conflict management, being: fight, collaboration, compromise, avoidance, and concession.” Alblas and Wijsman focused the concept of conflict management on the perceptions and behavioural choices of individuals in one-off interactions, while Katz and colleagues focused it on regularized institutionally-oriented interventions.

Although IR and OB still operate with differing logical conceptual norms, these norms should not be considered to be conceptual straightjackets. IR scholars using a SO logic could easily choose to experiment with a TP logic during the design stage of a research project and consider what doors such an approach would open or close. In the same fashion, OB scholars operating with a TP logic could attempt to experiment with an SO logic when planning a future project. Although many research questions would no longer make sense if a new logic of conflict were to be applied, the process of reaching such a conclusion would still provide a valuable opportunity for seeing the effect of operating under one logic of conflict as opposed to another. Accordingly, this exercise of “conflict logic perspective-taking” most certainly would still be worthwhile. Likewise, I do not aim in this paper to serve as a conceptual “mediator” by facilitating “resolution” between IR and OB by way of a single mutually-agreeable conceptualization of conflict. The aim instead is to offer both disciplines a more stable logical foundation upon which to hold future conversations and to encourage dialogue to begin. It is hoped that an acknowledgement by IR and OB scholars of the distinct conflict logic norms in their respective disciplines can provide new energy for such interdisciplinary dialogue. Even though SO and TP logics of conflict are irreconcilable, recognition of this fact by IR and OB conflict scholars could serve as a catalyst to reach one outcome that scholars seeking integration desire: a deeper and more fruitful engagement between the two disciplines, which can surely thrive despite the lack of a unified shared conceptualization of conflict.

Appendices

References

- Alblas, Gert and Ella Wijsman (2021) Organisational Behaviour. 2nd Ed. Groningen: Noordhoff.

- Avgar, Ariel C. (2020) “Integrating Conflict: A Proposed Framework for the Interdisciplinary Study of Workplace Conflict and Its Management.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 73(2), 281–311.

- Avgar, Ariel C. and Alexander J. S. Colvin (2017) “Introduction: Toward an Integration of Conflict Research.” In Ariel C. Avgar and Alexander J. S. Colvin (eds.), Conflict Management (Volume 1). New York: Routledge, pp. 1-37.

- Avgar, Ariel C. and Eric J. Neuman (2015) “Seeing Conflict: A Study of Conflict Accuracy in Work Teams.” Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 8(2), 65–84.

- Batstone, Eric (1979) “The Organization of Conflict.” In Geoffrey Stephenson & Christopher Brotherton (eds.), Industrial Relations: A Social Psychological Approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, pp. 55-74.

- Bendersky, Corinne, Julia B. Bear, Kristin J. Behfar, Laurie R. Weingart, Gergana Todorova and Karen A. Jehn (2014) “Identifying Gaps Between the Conceptualization of Conflict and Its Measurement.” In Oluremi Bolanle Ayoko, Neal M. Ashkanasy and Karen A. Jehn (eds.), Handbook of Conflict Management Research. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, pp. 79-89.

- Bradley, Bret H., Heather J. Anderson, John E. Bauer and Anthony C. Klotz (2015) “When Conflict Helps: Integrating Evidence for Beneficial Conflict in Groups and Teams Under Three Perspectives.” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 19(4), 243–272.

- Bray, Mark, John W. Budd and Johanna Macneil (2020) “The Many Meanings of Co-Operation in the Employment Relationship and Their Implications.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 58(1), 114–141.

- Budd, John W. (2020) “The Psychologisation of Employment Relations, Alternative Models of the Employment Relationship, and the OB Turn.” Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 73–83.

- Budd, John W. and Devasheesh Bhave (2019) “The Employment Relationship: Key Elements, Alternative Frames of Reference, and Implications for HRM.” In Adrian Wilkinson, Nicolas Bacon, Scott A. Snell and David P. Lepak (eds.), SAGE Handbook of Human Resource Management (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 41-64.

- Budd, John W., Alexander J. S. Colvin and Dionne Pohler (2020) “Advancing Dispute Resolution by Understanding the Sources of Conflict: Toward an Integrated Framework.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 73(2), 254–280.

- Chamberlain, Neil W. (1944) “The Nature and Scope of Collective Bargaining.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 58(2), 359–387.

- Contu, Alessia (2019) “Conflict and Organization Studies.” Organization Studies, 40(10), 1145–1462.

- Cutcher-Gershenfeld, Joel (1991) “The Impact on Economic Performance of a Transformation in Workplace Relations.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 44(2), 241–260.

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W. and Michele J. Gelfand (2008) “Conflict in the Workplace: Sources, Functions, and Dynamics Across Multiple Levels of Analysis.” In Carsten K. W. De Dreu and Michele J. Gelfand (eds.), The Psychology of Conflict and Conflict Management in Organizations. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 3-54.

- DeChurch, Leslie A., Jessica R. Mesmer-Magnus and Dan Doty (2013) “Moving Beyond Relationship and Task Conflict: Toward a Process-State Perspective.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 559–578.

- Edwards, Paul (1992) “Industrial Conflict: Themes and Issues in Recent Research.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 30(3), 361–404.

- Farber, Henry S. and Harry C. Katz (1979) “Interest Arbitration, Outcomes, and the Incentive to Bargain.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 33(1), 55–63.

- Fox, Alan (1974) Beyond Contract: Work, Power, and Trust Relations. London: Farber & Farber.

- Frangi, Lorenzo, Sung-Chul Noh and Robert Hebdon (2018) “A Pacified Labour? The Transformation of Labour Conflict.” In Adrian Wilkinson, Tony Dundon, Jimmy Donaghey and Alexander J. S. Colvin (eds.), Routledge Companion to Employment Relations. New York: Routledge, pp. 285-303.

- Gall, Gregor and Robert Hebdon (2008) “Conflict at Work.” In Paul Blyton, Nicolas Bacon, Jack Fiorito and Edmund Heery (eds.), SAGE Handbook of Industrial Relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, pp. 588-603.

- Godard, John (2014) “The Psychologisation of Employment Relations?” Human Resource Management Journal, 24(1), 1–18.

- Hartley, Jean (1988) “Psychology and Industrial Relations: Social Processes in Organisations.” International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 4(1), 53–60.

- Heery, Edmund (2016) Framing Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jehn, Karen A. (1995) “A Multimethod Examination of the Benefits and Detriments of Intragroup Conflict.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 256–282.

- Jehn, Karen A. (1997) “A Qualitative Analysis of Conflict Types and Dimensions in Organizational Groups.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 530–557.

- Jehn, Karen A., Lindred L. Greer, Sheen Levine and Gabriel Szulanski (2008) “The Effects of Conflict Types, Dimensions, and Emergent States on Group Outcomes.” Group Decision and Negotiation, 17(6), 465–495.

- Katz, Harry C. (2020) “Introduction to a Special Issue on Conflict and Its Resolution in the Changing World of Work: Honoring Professor David Lipsky.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 73(2), 253.

- Katz, Harry C., Thomas A. Kochan and Alexander J.S. Colvin (2017) An Introduction to U.S. Collective Bargaining and Labor Relations. 5th Ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kochan, Thomas A. (1998) “What is Distinctive about Industrial Relations Research?” In Keith Whitfield and George Strauss (eds.), Researching the World of Work. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 31-45.

- Kochan, Thomas A., Harry C. Katz and Robert B. McKersie (1986) The Transformation of American Industrial Relations. New York: Basic Books.

- Kochan, Thomas A., Christine A. Riordan, Alexander M. Kowalski, Mahreen Khan and Duanyi Yang (2019) “The Changing Nature of Employee and Labor-Management Relationships.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 195–219.

- Mikkelsen, Elisabeth N. and Stewart Clegg (2018) “Unpacking the Meaning of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research.” Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 11(3), 185–203.

- Mikkelsen, Elisabeth N. and Stewart Clegg (2019) “Conceptions of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research: Toward Critical Reflexivity.” Journal of Management Inquiry, 28(2), 166–179.

- Nieto-Guerrero, Manuel, Mirko Antino and Jose M. Leon-Perez (2019) “Validation of the Spanish Version of the Intragroup Conflict Scale (ICS-14).” International Journal of Conflict Management, 30(1), 24–44.

- O’Neill, Thomas A. and Matthew J. W. McLarnon (2018) “Optimizing Team Conflict Dynamics for High Performance Teamwork.” Human Resource Management Review, 28(4), 378–394.

- Park, Semin, John E. Mathieu and Travis J. Grosser (2020) “A Network Conceptualization of Team Conflict.” Academy of Management Review, 45(2), 352–375.

- Pondy, Louis R. (1967) “Organizational Conflict: Concepts and Models.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(2), 296–320.

- Riordan, Christine A. and Alexander M. Kowalski (2021) “From Bread and Roses to #METOO: Multiplicity, Distance, and the Changing Dynamics of Conflict in IR Theory.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 74(3), 580–606.

- Strauss, George (1977) “The Study of Conflict: Hope for a New Synthesis Between Industrial Relations and Organizational Behavior?” In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Meeting of the Industrial Relations Research Association. Madison: Industrial Relations Research Association, pp. 329-337.

- Tapia, Maite, Christian L. Ibsen and Thomas A. Kochan (2015) “Mapping the Frontier of Theory in Industrial Relations: the Contested Role of Worker Representation.” Socio-Economic Review, 13(1), 157–184.

- Thomas, Kenneth W. (1976) “Conflict and Conflict Management.” In Marvin D. Dunnette (ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 889-935.

- Thomas, Kenneth W. (1992) “Conflict and Conflict Management: Reflections and Update.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(3), 265–274.

- Walton, Richard E. and Robert B. McKersie (1965) A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Weingart, Laurie R., Kristin J. Behfar, Corinne Bendersky, Gergana Todorova and Karen A. Jehn (2015) “The Directness and Oppositional Intensity of Conflict Expression.” Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 235–262.

List of figures

Figure 1

Logics of Conflict in Industrial Relations and Organizational Behaviour