Abstracts

Abstract

New labour market intermediaries, such as those using digital platforms, are challenging not only temporary help agencies but also traditional employer–employee relationships. A new conceptual scheme is proposed to distinguish between three functions: a) allocating the work; b) entering into a contract with the worker; and c) managing and organizing the work.

By using this scheme in a study of 11 intermediaries of knowledge-intensive work in Norway, we found that self-service platforms are insufficient and must be supplemented with active client involvement during several stages of the allocation process. Such active involvement is driven by the complexity of the assignments and the client’s uncertainty about job requirements. Regarding management of the work, our findings contrast both with the common perception of independent contractors’ work as self-directed and with the idea that an intermediary can use algorithms to manage work. In reality, the contractor's work is managed in very different ways.

Our paper outlines several approaches that combine some or all of the three functions and adds to the literature by describing new forms of triangular work arrangements.

Keywords:

- Labour market intermediaries,

- allocation,

- digital platforms,

- contractor

Résumé

Les nouveaux intermédiaires du marché du travail, comme ceux utilisant les plateformes numériques, remettent en question non seulement les agences de placement temporaire, mais aussi les relations traditionnelles entre employeur et employé. Un nouveau schéma conceptuel est proposé pour distinguer trois fonctions : a) répartir le travail ; b) conclure un contrat avec le travailleur; et c) gérer et organiser le travail.

En utilisant ce schéma dans une étude portant sur 11 intermédiaires des travailleurs du savoir en Norvège, nous avons constaté que les plateformes en libre-service sont insuffisantes et doivent être complétées par l’implication active du client à plusieurs étapes du processus de répartition. Cette implication active est motivée autant par la complexité des affectations que par l'incertitude du client quant aux exigences du poste. En ce qui concerne la gestion du travail, nos résultats contrastent avec la perception courante du travail des entrepreneurs indépendants comme étant autodirigé, ainsi qu’avec l’idée qu’un intermédiaire puisse utiliser des algorithmes pour gérer le travail. En réalité, le travail de l'entrepreneur est géré de plusieurs manières très différentes.

En somme, nous décrivons plusieurs approches qui combinent tout ou partie de ces trois fonctions. De plus, nous enrichissions la littérature en décrivant de nouvelles modalités de travail triangulaires.

Mots-clés :

- Intermédiaires du marché du travail,

- répartition,

- plateformes numériques,

- entrepreneur

Article body

1. Introduction

New intermediaries in the labour market, such as those using digital platforms, challenge both temporary help agencies (THAs) and traditional employer–employee work arrangements (Howcraft and Bergwall-Kåreborn, 2019; Jesnes, 2019; Lévesque et al., 2020; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Vallas and Schor, 2020). These developments in the outsourcing of work led us to re-examine the existing conceptualization of nonstandard work arrangements and to investigate the consequences of the “new” arrangements. After examining the “new” intermediaries between firms and workers in the short-term work market,[1] we suggest changes to the conceptual scheme of nonstandard work arrangements. Thus, we aim to help conceptualize such arrangements and understand their challenges and implications.

With the development of Atkinson’s flexible firm model (Atkinson, 1981) and with increasing interest in “bringing workers back out” (Pfeffer and Baron, 1988), researchers have investigated how firms combine long-term employment relationships with nonstandard work arrangements. Depending on firm-related factors and external contingencies, such as labour regulations and market characteristics, companies may use direct temporary employment contracts, freelancers/independent contractors, leasing from a third party (e.g., a THA) or services provided by contract companies (e.g., consultancy firms). The state-of-the-art article by Cappelli and Keller (2013) provides the conceptual basis for this analysis of work arrangements.

Recent decades have seen the emergence of intermediaries that use digital platforms to allocate short-term work, as well as increased attention to contract work and outsourcing of labour by other means (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Vallas and Schor, 2020). Little has been learned, however, about how these developments challenge the conceptualization of nonstandard work arrangements. Thus, there is still a knowledge gap in understanding the different functions of such intermediaries and how these actors are similar to or different from other third parties in the labour market. Such “what is” knowledge is vital to understand the implications and consequences of changes in work organization.

Building on Roverud et al. (2017), we will identify and explore three functions of intermediaries in the labour market: (i) allocating the work—matching human resources with the client organization; (ii) entering into a contract with the worker; and (iii) managing and organizing the actual work.

We have three research questions: What is the role of intermediaries in each of the three functions? To what extent are digital tools used to allocate work? What combinations of functions are found among intermediaries, and how do these combinations differ from existing conceptualizations of intermediaries? We will also highlight the implications for understanding of work organization and work arrangements.

Because this empirical study was conducted in Norway, we were able to understand the intermediaries in a highly regulated and organized national context. By interviewing representatives of 11 intermediaries involved in knowledge-intensive work, we were also able to capture the challenges of allocating human resources and managing the work with a certain level of abstraction and complexity.

2. Previous Research and Literature

2.1 Nonstandard Work Arrangements: Conceptualizations

Researchers have addressed several aspects of work and organizational flexibility (Ashford et al., 2007; Atkinson, 1984; Kalleberg, 2011; Nesheim, 2004; Pfeffer and Baron, 1988; Vallas and Schor, 2020), including worker vs organizational flexibility, numerical vs functional flexibility, how various work arrangements contribute to flexibility and precarity and the institutional factors and regulations relating to such work arrangements.

In Atkinson’s model, a flexible firm combines long-term attachment of labour and functional flexibility at the firm’s core with numerical flexibility and nonstandard work arrangements at the firm’s periphery, such as short-term hires, contractors and sub-contractors (Atkinson, 1984). Pfeffer and Baron (1998) distinguish among three situations that lead to outsourcing: organization of work across different geographic locations; short-term work contracts; and lack of administrative control by the focal firm. Building on these and other contributions, Cappelli and Keller (2013) have provided a conceptual synthesis of work arrangements that is based on “the theoretical construct of control—specifically, how control over the work process governs the relationship between the worker and the organization that benefits from the worker’s efforts” (Cappelli and Keller, 2013, p. 577).

The authors distinguish between:

Employment and contractual arrangements, which are underpinned by employment law and contract law respectively. In employment relationships, the firm has directive control, while this is not the case in contract relationships.

Two-party vs triangular relationships.

Thus, employment relationships include full-time, long-term relationships, direct short-term hires and co-employment/triangular relationships (such as personnel from a THA). Contract work includes the two-party relationships a client organization has with independent contractors and the triangular relationships it has with vendors on the premises and with contract companies. When the arrangements have three parties, i.e., the worker, the third party and the client organization (Cappelli and Keller, 2013; Kalleberg et al., 2003; Olsen, 2006; Pfeffer and Baron, 1988), the basic distinction is between:

arrangements where the third party employs the worker, and the client organization directs the work; and

arrangements where the third party both employs the worker and directs the work, i.e., a vendor on the premises or a contract company.

Thus, triangular work arrangements are defined by two third-party functions: entering into a contract with the worker (same function in both forms of work arrangement, i.e., an employment contract) and organizing and directing the work (different functions in each form of work arrangement).

Figure 1

Classification of Economic Work Arrangements (Cappelli and Keller, 2017: 577)

2.2 First Challenge to the Conceptual Scheme: A Third Party as the Allocator of Contractors

An employment arrangement deviates from the above diagram when the relationship between the independent contractor and the client organization is mediated by an intermediary organization. In their study of contract work, Barley and Kunda (2004) found that the intermediary between the worker and the client organization performed vital tasks. While two out of three third-party intermediaries in their study were employers, the third one had contractual relationships with the workers. The intermediary was instrumental in matching the client organization’s demands with the supply of workers. Because both sides often had limited networks of contacts, a market niche opened up for intermediaries. In a study from Norway, it was found that ordinary employees often worked in teams with external consultants, some of whom were contractors. Here, the client organization preferred to have an intermediary between itself and the consultants. The intermediary would help select the consultants and thus reduce the number of direct contracts (Nesheim et al., 2014).

That system is a hybrid between a purely independent contract and a triangular relationship. Examples are also found in the literature on digital intermediaries (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019 Meijering and Arets, 2020), but the workers may exist independently of such intermediaries, as the examples above show. The hybrid differs from a THA arrangement because the worker is a contractor, rather than an employee of the intermediary.

Thus, there are instances where third parties act primarily as mediators or matchers who do not direct or control the work. That situation is an anomaly in relation to the conceptualization of triangular work arrangements (Cappelli and Keller, 2013), since the actors do not “fit” into any of the categories. The anomaly may be resolved by giving the intermediary a third function: allocating the work, where a client organization that needs to get a set of tasks performed is matched with a worker who has the capacity and skills to perform them. Here, one may expect variation in the magnitude of the processes involved in allocating, be it providing “information” or making a more active contribution through “matchmaking” (Bonet et al., 2013).

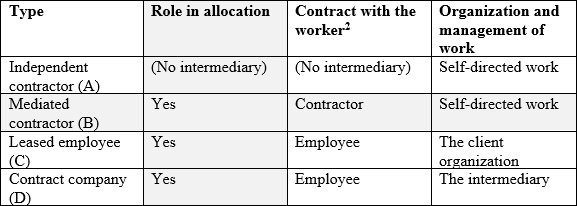

In Table 1, a new conceptual scheme is presented that adds the allocation function and acknowledges that third parties can enter into contracts with an employee or a self-employed worker. Four types of arrangements are described, and the mediated contractor (B) is in a new “form” of arrangement that lies between the worker as independent contractor and the worker as leased employee in a triangular arrangement.

Table 1

Functions of Labour Market Intermediaries

2.3 Second Challenge to the Conceptual Scheme: Digital Platforms for Work

In the last decade, much attention has been paid to digitally based platforms that match workers and client organizations. Examples are found in transportation (e.g., Uber), cleaning (e.g., Helplink), household do-it-yourself (e.g., TaskRabbit) and programming (e.g., Clickworker) (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019, p. 214). These work arrangements may also be described as crowdsourcing (Nakatsu et al., 2014), e-lancing (Aguinis and Lawal, 2013), independent contracting, “work on demand via [an] app” (Aloisi, 2016), platform work, gig work, or interim/freelance project work (Keegan et al., 2018).

Such work has been classified along several dimensions: skill level; nature of the work; degree of worker control; whether the work is performed online or offline; and type of product or service (Bucher et al., 2021; Frenken and Schor, 2017; Howcroft and Bergvall-Kåreborn, 2020; Kalleberg and Dunn, 2016; Vallas and Schor, 2020).

Workers with such arrangements are a challenge to conventional thinking in both research and regulation “because they fall through regulatory and conceptual gaps created by systems based on the notion of traditional employment” (McKeown, 2016, p. 780). Whether or not they are employees is a question for courts around the globe (see, for instance, Coiquaud and Martin, 2019; Jesnes and Oppegaard, 2020; Wang and Cooke, 2021).

The literature provides insights into the three different functions described above. First, intermediaries typically enter into service contracts with self-employed workers or contractors rather than into employment contracts. Second, research suggests that platform companies use technological tools to perform the allocation function (Ajuna and Greene, 2019; Kenney and Zysman, 2016). They match workers and clients by collecting data (worker and client registrations, ratings and, sometimes, GPS data) and by using algorithms. In a study of Upwork, Jarrahi et al. (2020) found that allocation was neither automatic nor strictly digital but instead relied on “worker and client participation in filling out descriptions, scrolling through possibilities, contacting each other, and negotiating a job” (Jarrahi et al. 2020, p. 181). The premise of pure digital allocation is thus questionable.

Algorithmic management (Kenney and Zysman, 2016; Lee et al., 2015) opens up the possibility of managing work by monitoring it, measuring it and charting its direction (Claussen et al., 2018; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Wood et al., 2018; Meijerink and Arets, 2020). As Meijerink and Keegan (2019) put it: “… an intermediary platform firm … installs an online platform that matches and manages gig workers and requestors [italics added] (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019, p. 215). Although such firms control several activities, they may cede control over other activities, such as specifying work methods, controlling work schedules and evaluating performance (Vallas and Schor, 2020).

Thus, to a large extent, this strand of research tends to assume that the allocation of tasks is an algorithm-supported digital process that differs markedly from a process that involves human relationships. It is also assumed that a technological platform enables the intermediary to manage and organize work activities.

3. Data and Methods

This empirical study is based on information from 11 intermediaries who were active in the Norwegian labour market at the time of data collection (2021). To capture organization-mediated work arrangements (cf. Cappelli and Keller, 2013), we chose intermediaries that targeted private sector firms or public-sector units (rather than persons as clients). We were primarily interested in work that required formal education, performance of complex abstract tasks and dialogue with clients (cf. Jarrahi et al., 2021).

We first identified potential intermediaries via Internet searches, contacts and previous studies of such companies (Fabo et al., 2017; Røtnes et al., 2019), while excluding traditional THAs and consultancy firms (with employees) that provided client organizations with services and human resources. Thus, we excluded well-known intermediaries between work providers and client organizations, notably types C and D in Table 1 above. We sought intermediaries that provided other functions or combinations of functions than those supplied by established actors and which differed from types C and D.

A total of 23 intermediaries were contacted. Five of them fell outside the scope of the study, since they were pure THAs, served personal clients (rather than client organizations) and/or represented low-skill workers. Seven of the remaining 18 declined to take part in the study or did not respond to our inquiries. For each intermediary, we interviewed the CEO or another manager. Seven of the 11 were in the ICT field, 2 were in content marketing/journalism, 1 represented interim managers, and 1 mainly served the culture industry. The number of workers they represented ranged from 100 to 10,000 per year.

Generally, Norway has a highly organized labour market for both the worker and the employer, an advanced welfare state and low unemployment (Olsen, 2006). Collective agreements and the comprehensive Work Environment Act both aim to protect two-party, open-ended employment arrangements as the standard work arrangement. While such provisions create a demand for nonstandard work arrangements, the supply of nonstandard workers is restricted by limitations on the leasing of employees from THAs (Type C in Table 1) and on the client organizations’ use of independent contractors (Type A in Table 1). Norwegian labour law does not specifically cover intermediaries that represent contractors or similar “types” of workers (NOU, 2021).

We conducted the interviews via Teams with an external recording machine from May 2021 to January 2022. The interviews lasted 60–90 minutes and were semi-structured. They addressed the background and history of each case, the perceptions of the market and the competitors and the intermediary’s three functions: allocating the work; entering into a contract with the worker; and managing and organizing the work. All the interviews were transcribed.

We analyzed the data with a view to capturing the way each of the three functions was executed. The main themes that emerged were the degree of digitalization (in allocating human resources), why contracting rather than employment was chosen (entering into contracts) and variation in managing and organizing the work.

4. Empirical Results

4.1 Allocation Function

Simply put, contractors are matched with firms mainly through an algorithm-based self-service platform or through active, human-intensive allocation.

4.1.1 Algorithm-Based Self-Service Platform

A self-service platform uses algorithms to match the “best” contractor with the client’s request. The client organization gets access to the platform and performs searches based on different criteria. Sometimes, contractors can also search for jobs on the platform. The process was described by a CEO:

Can we build a platform, i.e., an online marketplace for consulting services that clients can enter and, completely on a self-service basis, pick the contractor they want, [and] make direct contact without us as a broker? The clients can enter the platform, browse, find contractors, get in touch with the most interesting ones, and invite them for an interview.

CEO, Firm #3

The online information about contractors includes availability, education, skills and, sometimes, client ratings. Contractors create their own profile and are allowed to brand themselves in the best possible way.

In the second model of a self-service platform, clients post the assignments themselves. They log into the service, create an assignment, set a budget and a deadline and choose the best suited contractor. Firm #8 uses this model.

4.1.2 Human-Intensive Allocation

While several companies sought originally to create a self-service platform, the challenges pushed them toward a more active matching model where candidates would be allocated to assignments on the basis of their skills. This process was described by another CEO:

… we are quite strict with the client and ask, ‘What do you really want?’ If the client is good at describing the role and in setting requirements, the easier it is to find the best contractor […]. We put the information in our marketplace so that all our contractors have access to it. Then, applications are received, and we assess the candidates.

CEO, Firm #10

Clients said that their active involvement in the process was driven by two factors: the complexity of the work and their uncertainty about job requirements.

4.2 Complexity and Knowledge-Intensive Work

Assignments from clients are often perceived as too complex and person-dependent to fit into a standardized template. The vacant position has to be specified and time is needed to find a suitable person, as one manager stated:

We need to understand what the contractors can deliver, if they are able to do the job, as well as to understand what the client needs.

Manager, Firm #5

Managerial positions are one source of complexity, as a CEO explained:

We have program managers who govern several projects—sub-projects that involve a lot of people. It is very important that the contractors function well in this role. The role is complex and is not only dependent on what the contractor has done before but how he/she is as a person […]. We need tests, several interviews; it is almost like a process of recruitment for employment.

CEO, Firm #2

Other assignments may respond to shortages of workers with certain types of skills or to a sudden, unpredictable demand for personnel. The second situation is described by another CEO:

There are plenty of situations where the clients need a contractor, and not acting fast has a big cost. There might be acute illness, death, changes in ownership. The latter is often the case; someone buys a start-up business and wants to take this further, implement smart solutions and grow in several countries. Then a specific type of manager skills is needed.

CEO, Firm #10

4.3 Client: Uncertainty about Job Requirements

A vital aspect of the matching function is to determine what the client needs. Many of the interviewees pointed out that the client often lacks knowledge of the human resources needed for a specific job. This point was explained by a manager:

There are so few clients who know what they actually need, so they have to talk with someone about it. And that is where we enter the scene. They need actors like us and a competent person to help them describe what they need, and then find this person.

Manager, Firm #5

In addition, our interviewees also said that the client may have time and resource constraints. Some clients find it time-consuming to use a self-service platform:

When the big companies entered the self-service platform, they stopped the process halfway because they saw that they had to do the job—[…] contact […] discuss […] do the interview […]. [They] do not bother to do that process, and then they need people like us.

Manager, Firm #5

Thus, assignment complexity and client uncertainty have increased the challenges of self-service, algorithm-based platforms. The resulting change is described by a CEO:

We started by creating a super simple platform where freelancers could create their own profile, post some pictures and set an hourly rate. Clients could enter the platform, contact them and filter on a few different elements. […] Then we figured out that we had to help the clients find freelancers. Therefore, we changed the model from an open marketplace to a closed marketplace, where we internally recruit freelancers.

CEO, Firm #7

4.4 Contracting instead of Employing

Among the intermediaries in the study, one firm stands out. Firm #11 has relationships with employees (rather than contractors) and thus acts as their formal employer. It handles the administrative tasks, bills the client for the work and provides the worker with benefits, such as social insurance, pensions and paid sick leave. As an employer, the intermediary does not guarantee a certain amount of work or a certain wage. For that, the employee bears the risk. The firm has no role in allocating the work but is fully responsible for the worker. Work for the client organization is typically self-directed and does not involve the intermediary.

The firm’s founder realized that it could do the administrative tasks for an assignment, instead of having them done by contractors. It initially targeted cultural workers (contractors) who were doing “gigs” for client companies, e.g., work related to events, celebrations and kick-offs. Today, those workers appreciate being employed by Firm #11 because it simplifies their relationship with the labour market. They are free to focus on developing their acts and skills, on obtaining gigs and on performing the actual gigs. The number of such “gigs” ranges from a few per year to the equivalent of a full-time position. Many of these workers also combine their employment at Firm #11 with other employment positions.

As for the other 10 firms, 99% of their contracts with workers are service contracts between the independent contractor and the intermediary. These bilateral agreements “mirror” the agreement between the intermediary and the client organization in terms of contract length and compensation (minus the intermediary’s cut).

Contractors are considered to be independent entities who bear the risks of their own business (income, sick pay, holiday pay, pensions, etc.). Some intermediaries specify that the contractor must have a private limited firm (AS) or sole proprietorship (ENK), thus signaling clearly that they do not want to enter into an employment relationship. A private limited firm is considered to be a separate legal person, and thus the risk for the contractor is less. In a sole proprietorship, the contractor is personally liable for the firm’s finances and obligations.

For some intermediaries, the human resource contracts are not restricted to direct contracts with self-employed workers. Three firms in our study also allocate employees of small and medium-sized consultancies to client organizations, thus creating four-party relationships: employee – consultancy firm – intermediary – client organization. By combining the input of personnel from contractors and firms, these intermediaries can draw on a larger pool of human resources and are thus better able to meet the demands of client organizations.

Firm #9 uses another combination of human resource contracts. In addition to acting as a mediator for contractors and personnel from consultancy firms, it has employees on regular contracts who are allocated to its clients. Thus, the firm also resorts to Type C, i.e., leasing of employees, as with THAs. As an outcome of mergers, the intermediary can now provide client organizations with “heads” through three different work arrangements. Recruitment of “heads” is delegated to a partner manager and an in-house recruitment department (employees). The firm is the only labour intermediary that combines brokering of personnel with allocation of its own (employed) consultants. While this setup complicates the firm’s structure, the perceived benefit is the ability to deliver appropriate personnel for specific assignments. The firm feels it has a higher level of flexibility than a pure THA and can provide longer-term solutions than a pure broker.

On the human resource side, intermediaries have short-term contracts with workers (for services, not employment), sometimes combined with other sources of personnel. A short-term contract carries no promise of further assignments, and the contractor may also be registered with other intermediaries and thus part of their “resource pool.” Our interviewees said that in general there are no restrictions on such “multi membership” and that they often preferred loose relationships, rather than running the risk of getting into a relationship of dependence on the workers. However, a few intermediaries were trying to develop an informal group of “preferred contractors,” thus emphasizing longer-term relationships.

Most intermediaries avoid a direct formal contract between the worker and the client organization. However, one intermediary (Firm #1) facilitates direct contracts between the client organization and the contractor without taking part in the agreement. This role accounts for approximately 50% of the contracts enabled by the firm. Another intermediary (Firm #4) has had experiences where a client organization and contractors, after being matched by the intermediary, made arrangements among themselves that excluded the intermediary. This was described as a challenge by that firm.

4.5 Managing and Organizing Work

After the client and worker have been matched and the contracts signed, the actual work must be managed, organized and executed. We found that contractors usually perform decomposable tasks unsatisfactorily (cf. Cappelli and Keller, 2013) and that parties other than the contractor manage the work.

4.5.1 ICT Skills: The Client Organization Directs the Work

The seven intermediaries for specialized ICT skills stated that, typically, extra capacity or specialized skills are provided to a team or project at a client organization. The contractor is allocated to an existing team or becomes a project member from the start. The client organization, not the intermediary, organizes the work, which is typically performed at the client’s site or by using digital tools independently of the intermediary. Thus, the organization of work shows a pattern similar to that of THAs and employee leasing.

Several interviewees said that demand in their market had been shifting from delivery of project teams toward delivery of single individuals and from customized products to allocation of specialized “heads.” Previously, they “… needed an external team to do a (development) job for 1.5 years and then hand it over to the IT department” (CEO, Firm #3). Now, client organizations typically have a different and more strategic approach to IT:

IT and digitalization are core activities; everyone has understood this […] everyone has started to use a lot of money to build strong in-house IT skills. Now, they need single consultants to fill a gap in skills and capacities in in-house teams.

CEO, Firm #3

An assignment by an intermediary to a client organization may last for several years. The interviewees typically said that the average length of stay is between 1 and 2 years. In the words of one of them, “We sign and prolong contracts for 6 or 12 months at a time. A lot of our consultants have very long engagements” (CEO, Firm #3).

Large client organizations often have a range of demands for contractors. A consultant’s assignment may thus be long-term, as shown by the following quote:

The large client companies have a continuous need for development. Therefore, contracts are often prolonged because it is costly to get hold of new contractors, and it is also costly to introduce new contractors to a particular domain, regardless of whether it is telecoms, a bank or finance. So you often find that people remain (with the same client organization) for several years, if they are satisfied.

CEO, Firm #3

One intermediary emphasized that client organizations tend to look for several contractors to join a team rather than individual assignments:

We experience that team staffing has become more relevant. What we do is to construct a team, do assessments and tests […]. We check what they have done before, how they function, and then sell the contractors as a team. […] We just select the contractors […]. The client is responsible for the (performance of) the team.

CEO, Firm #2

4.5.2 The Intermediary Directs the Work

Two of the intermediaries tended to take a more active role in managing and organizing the work. Firm #8 provided content marketing skills and usually played an active role in the assignments:

Among key clients, we have an active role in the project. Also, among other clients, we use project managers (contractors) to provide project management (on our behalf).

CEO, Firm #8

Thus, Firm #8 typically provided a client organization with a product, rather than allocating human resources for the client to manage. The intermediary would assemble a team who would provide a solution to the client’s “problem.” The interviewee gave the example of a contract from 2019, when a client wanted a printed magazine with 100 pages. According to the interviewee, none of the traditional communication firms were able to do the job because of a lack of staff:

What we did was that, even though we were only three people at the office, in two days we had assembled a team of 14 people with photographers, writers, lay-out, project managers and so on. We managed to deliver within a month.

CEO, Firm #8

The interviewee emphasized the advantage of flexible contractor staffing in creating complex products for client organizations over a short time span. When the activity is content marketing, the focus is on product skills rather than on people skills, as may be explained by the client’s skill profile:

If you work in a communication department, it does not necessarily follow that you know how to produce a magazine. It takes editorial skills and an understanding of a certain workflow, and you need to have experience. Usually, the clients don’t have the relevant skills.)

CEO, Firm #8

In addition, clients need help in specifying the product they want. While they typically know what they want in terms of sales, they often lack the necessary knowledge of how to achieve that outcome. As a CEO explained:

They may read a text, and find it OK, but they are not able to place an order. They are not able to identify what kind of story they want. They are dependent on people who have content skills and know which stories hit it off with the (potential clients) and which stories do not.

CEO, Firm #8

Firm #7 provides skills for digital visual services, such as creation of web pages, visualization of brands and production of animation videos, digital flyers, presentations, etc. In contrast to Firm #8, it does not provide a client organization with products or services. However, the intermediary still influences management of the work through the technology of the digital platform. Rather than having people manage the work on behalf of the intermediary (such as Firm #8), the digital platform’s tools enable and influence how the work is done, as the CEO explained:

We have a responsibility for the outcome, but as a rule we don’t intervene in the process. The client and, for example, the designer communicate directly on the platform […]. The client gets a [digital] project room where they communicate with the contractors and share files. Instead of having 34 email threads, you get everything on one site. This is valuable [for the contractors] [because] in relation to what the client can offer, they use the tools, share files, chat and communicate directly. We may access the communication and support both parties if they ask for it.

CEO, Firm #7

4.5.3 The Contractor Manages the Client Organization

Finally, Firm #10 differs from the other intermediaries in the role played by the contractor. The contractor acts as an interim manager, being temporarily assigned as a top manager (CEO), functional manager or project manager in the client organization. While interim managers report hierarchically to a board or a manager, their main role is to direct and manage the work of the middle managers or employees of the organization. The intermediary does not play an active role during the contract period but is involved in some coaching with the contractor.

5. Overview and Discussion

Table 2

Overview of Intermediaries and Functions

5.1 Functions of the Intermediaries

An overview is given in Table 2. First, let us review each of the three functions of the intermediaries. Regarding allocation of the work, intermediaries that initially intended to allocate it through digital matching found a self-service platform to be insufficient. This finding supports that of Jarrahi et al. (2020): not all forms of work are suitable for or more efficient with algorithmic matching and must be supplemented with active client involvement during several stages of the allocation process. Such active involvement is driven by the complexity of the assignments and by the client’s uncertainty about job requirements.

All intermediaries enter into contracts with independent contractors, except for Firm #11, which specializes in acting as the employer, while the worker is responsible for obtaining “gigs” from client organizations.

Regarding management and organization of the work, our findings contrast both with the perception of self-directed work of independent contractors (Cappelli and Keller, 2013) and with the idea that intermediary-based algorithms can be used to manage work (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019). In reality, the contractor’s work is managed in a variety of ways. For the seven intermediaries in the ICT industry, the client organization directs the work. To a large extent, this type of management is due to the specific demands of the clients, who are seeking “heads” to supplement their own employees. In one case, the intermediary directs the work (Firm #8). In another case (Firm #7), the tools available on the intermediary's digital platform influence how the work is executed. Finally, in the case of Firm #10, which provides managers, the contractor manages the work of the client’s employees at different levels, depending on the specific managerial role. That finding is consistent with Anderson and Cappelli (2020).

5.2 New Forms? Combinations of Functions

In addition to our findings on each function, there are also those on different combinations of the three functions. These combinations challenge the current conceptualization of nonstandard work arrangements (Cappelli and Keller, 2013). In particular, they indicate the following “new” work arrangements:

The intermediary matches contractors with clients, and the client organization manages the work of the contractors. This “mediated contracting” builds on Table 1. It is similar to employee leasing (Type C), except for having contracts with independent contractors instead of employment relationships (Firms #1–6).

The intermediary matches contractors with clients, and the intermediary plays a key role in managing the work. This work arrangement is similar to that of client companies or vendors on premises (Type D), except for the type of contract with the contractor (Firms #7 and 8).

The intermediary matches contractors with clients, and contractors work directly at the client organization. As with the first work arrangement, described above, control is executed within the client organization, where the contractor acts as the manager (Firm #10).

The intermediary has no role in matching workers and clients. The intermediary acts as a formal employer, and the workers have employment contracts. The work for the client organization is mainly self-directed (Firm #11).

5.3 Discussion

For a client organization, the use of an intermediary to provide “heads” and/or services is an alternative to standard open-ended contracts. The combinations of functions found here differ from those of traditional THAs and contract companies. The new work arrangements provide the client with new options, whose potential impact is to increase the magnitude and variety of outsourcing of work. Since the workers are mostly contractors, and not employees, such outsourcing tends to place the burden of risk on the worker, rather than on the employer.

Much research has been conducted on digital-based intermediaries in the labour market. One contribution of our study is that it challenges a simplified view of the “new outsourcing” and provides a more nuanced understanding of algorithmic allocation and management. Here, it is essential to differentiate between allocating and managing. While digital allocation of workers to client organizations is undoubtedly a vital development in the labour market, underpinned by the potential savings in transaction costs and the positive network effects of platforms, our results support the existence of boundaries to the self-selection allocation model (Jarrahi et al., 2020). Future research should look into the implications of knowledge-intensive work for allocation mechanisms.

Intermediaries may also have a role in managing the work, but our empirical study shows variation in who actually directs and manages the work. Thus, it should not be assumed that the existence of an intermediary with a range of technological tools implies a role in work management. It is rather the nature of the demand from the client organization that is the main influence on work management. This is especially so when the intermediary provides a client with “heads”: it tends to manage the “heads” itself, using in-house software and other tools.

The growth in new intermediaries is also related to institutional regulations and labour market systems (Degryse, 2020; de Stefano et al., 2021; Ratti, 2016). Since such regulations tend to be specific to each country, those in Norway have to be considered. The Norwegian labour market is characterized by an advanced welfare state built around the dyadic relation between an employer and an employee, strong social partners and a centralized collective bargaining system (Røtnes et al., 2019). In this labour market system, the intention is to maintain an open-ended two-party employment relationship as the standard form, and labour law and collective agreements are used to protect employees in such relationships (NOU, 2021). Organizations thus tend to push for “looser” employment arrangements (e.g., use of THAs, freelancers and self-employed workers), and efforts are made to limit such options through provisions in law and collective agreements (NOU, 2021).

When workers are allocated to client organizations through intermediaries based on digital platforms, there may arise new arrangements not covered by such provisions. In a fast-changing world of work, the emergence and use of such intermediaries may, intentionally or unintentionally, escape institutional regulations (cf. Oliver, 1991) or have an ambiguous status in relation to them. For example, when ICT contractors are allocated to a client organization to be managed by the same organization, that arrangement is consistent with the provisions on the use of THAs and employee leasing. However, workers in such “mediated contracting” as described here are not employed by the intermediary, and if one insists on their status as contractors, such use of external workers is allowed only when they direct their own work.

Our findings from Firm #11 illustrate another issue of labour law. The intermediary presents itself as the worker’s formal employer, while having no role in or responsibility for providing work. Such positioning in the market for short-term labour may challenge the implicit assumption that the employer is responsible for providing the employee with a certain amount of work. In the Norwegian context, the issue of what the employer’s role entails, especially whether it includes providing a specific amount of work, surfaced in discussions of new provisions on zero-hour contracts (NOU, 2021). Thus, by raising awareness and causing an explicit re-assessment of what an employer’s role entails, such discussions may have consequences for Firm #11 and similar firms.

Thus, some of our findings may tend to be general in nature: existence of more options for the client organization; nuanced understanding of the level of digitalization among intermediaries; and challenges to labour market systems. Other findings, like challenges to a country’s existing provisions (see above), need to be related to the specific labour market context. The characteristics of Norway’s labour market may also influence access to the different types of intermediaries in our study. Therefore, our sample may exhibit variations and magnitudes that differ from those of samples in other countries with different labour market systems. The generalizability of our findings will depend on such factors as the high incidence of standard employment arrangements in Norway, which makes intermediaries less attractive to workers, the potential savings of escaping labour regulations, which make new intermediaries more attractive to clients, and the attractiveness of certain skills in the labour market, which makes certain new intermediaries and workers more attractive.

6. Conclusion

In this study we have examined how new labour market intermediaries and platforms challenge both standard work arrangements and well-known intermediaries, such as THAs and contract companies. By studying 11 intermediaries that bring together workers (mostly contractors) and client organizations in the labour market, we have brought new insights into understanding of work arrangements, in particular triangular relationships. Our analysis makes several contributions, each of which may point the way to further avenues of research. First, we have clarified the allocation function of third parties, which can play a role not only in providing the worker with contracts but also in managing and directing the work. Second, rather than relying solely on a digital algorithm-based platform, most intermediaries in our study actively allocate the workers. That role is driven by assignment complexity and client uncertainty. Third, while previous research (Cappelli and Keller, 2013) has typically assumed that contractors direct their own work, our findings indicate other arrangements: work directed by the client organization; work (fully or partly) directed by the intermediary; and contractors managing work at the client organization (in the case of interim managers). Fourth, our findings suggest several ways in which the three functions are combined and paint a nuanced picture of forms of triangular work arrangements. Fifth, we have shown how new intermediaries challenge existing labour market regulations within the context of a particular set of regulatory and institutional arrangements.

Based on our contributions, more progress could be made in understanding the rationale for and the specific mechanisms and challenges of outsourcing of work. The intermediaries we identified provide several means whereby workers may “be taken back out.” Questions for further research include: What are the mechanisms for allocation of work and the dynamics and tensions of algorithm-based and active allocation? In triangular employment relationships, what are the patterns in management of the actual work, and what factors influence the use of different mechanisms for such management? Of the possible types of intermediaries, which one(s) will become sustainable and institutionalized over time, as opposed to being submerged into such traditional intermediaries as THAs and contract companies? To what extent will niche actors, such as those specializing in handling employment relationships (cf. Firm #11), survive and thrive? How do different employment models at the national level influence the amount of contract work and the role and incidence of various types of intermediaries?

Appendices

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Arne L. Kalleberg, Kenan Distinguished at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for comments on a previous draft of this paper.

Notes

-

[1]

Please note that the concept of worker refers to a person with labour power and skills who is doing the actual work. The worker may be an employee (with an employment contract) or a contractor (with a service contract).

-

[2]

Please note that contract companies that recruit for permanent employment (rather than providing workers for short-term work) do not fall within this paper’s scope.

References

- Aguinis, Herman A. and Sola O. Lawal (2013). eLancing: A review and research agenda for bridging the science–practice gap. Human Resource Management Review 23: 6-17.

- Ajunwa, Ifeoma and Daniel Greene (2019). "Platforms at Work: Automated Hiring Platforms and Other New Intermediaries in the Organization of Work" In Work and Labor in the Digital Age. Published online: 14 Jun 2019; 61-91. DOI: 0.1108/S0277-283320190000033005.

- Aloisi, Antonio (2016). Commoditized Workers. Case Study Research on Labour Law Issues Arising from a Set of 'On-Demand/Gig Economy' Platforms (May 1, 2016). Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal 37: (3), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2637485 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2637485

- Anderson, Tracy and Matthew Bidwell (2019). Outside insiders: Understanding the role of contracting in the careers of managerial workers. Organization Science 30(5): 1000-1029.

- Anderson, Tracy and Peter Cappelli (2020). Management without managers: Expanding our understanding of managing through the study of contractors. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3875634.

- Ashford, Susan J., Elisabeth George and Ruth Blatt (2007). Old assumptions, new work: The opportunities and challenges of research on nonstandard employment. I J. P. Walsh and A. Brief (eds.), The Academy of Management Annals 1: 6–117. Mahwah, NH: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Atkinson, John (1984). Manpower strategies for flexible organisations. Personnel Management 16: 28-31.

- Barley, Stephen R. and Gideon Kunda (2004). Gurus, Hired Guns, and Warm Bodies: Itinerant Experts in a Knowledge Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bonet, Rocio, Peter Cappelli and Monika Hamori (2013). Labor market intermediaries and the new paradigm for human resources. The Academy of Management Annals 7: 341-392.

- Bucher, Elianne Leontine, Peter Kalum Schou and Matthias Waldkirch, Matthias (2021). Pacifying the algorithm – Anticipatory compliance in the face of algorithmic management in the gig economy. Organization 28(1): 44–67.

- Cappelli, Peter and JR Keller (2013). Classifying work in the new economy. Academy of Management Review 38: 575-596.

- Claussen, Jørg, Pooyan Khashabi, Tobias Kretschmer and Marieke Seifried (2013). Knowledge work in the sharing economy: What drives project performance in online labor markets? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3102865.

- Coiquaud, Urwana and Isabelle Martin (2019). Access to Justice for Gig Workers: Contrasting Responses from Canadian and American Courts. Relations Industrielles Industrial Relations 74(3): 577-588.

- Degryse, Christophe (2020). Du flexible au liquide : le travail dans l’économie de plateforme, Relations industrielles/industrial relations. 75(4): 660-683.

- De Stefano, Valerio, Ilda Durri, Charalampos Stylogiannis, and Mathias Wouters (2021). Platform work and the employment relations, ILO Working papers 27.

- Fabo, Brian, Miroslav Beblavý, Zakhary Kilhoffer and Karolien Leonards (2017). An overview of European platforms: Scope and business models: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Frenken, Koen and Juliet B. Schor (2017). Putting the sharing economy into perspective. A research agenda for sustainable consumption governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Howcroft, Debra and Birgitta Bergvall-Kåreborn (2018). A Typology of Crowdwork Platforms. Work, Employment and Society.

- Jarrahi, Mohammed H., Wil Sutherland, Sarah Beth Nelson and Steve Sawyer (2020). Platformic management, boundary resources for gig work, and worker autonomy. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 29(1): 153-189.

- Jesnes, Kristin (2019). Employment Models of Platform Companies in Norway: A Distinctive Approach? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 9(S6). https://doi.org/10.18291/njwls.v9iS6.114691

- Jesnes, Kristin and Sigurd M. N. Oppegaard (2020). Platform work in the Nordic models: Issues, cases and responses: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Kalleberg Arne L. (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kalleberg Arne L. and Michael Dunn (2016). Good jobs, bad jobs in the gig economy. LERA for Libraries 20.

- Kalleberg, Arne L., Jeremy Reynolds and Peter V. Marsden (2003). Externalizing employment: Flexible staffing arrangements in U.S. organizations. Social Science Research 32: 525–552.

- Kenney, Martin and John Zysman (2016). The rise of the platform economy. Issues in Science and Technology 32: 61.

- Kuhn, Kristine M. and Amir Maleki (2017). Micro-entrepreneurs, dependent contractors, and instaserfs: Understanding online labor platform workforces. Academy of Management Perspectives 31: 183-200.

- Lee Min Kyung, Daniel Kusbit and Evan Metsky (2015). Working with Machines: The Impact of Algorithmic and Data-Driven Management on Human Workers. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Seoul, Republic of Korea: ACM, 1603-1612.

- Lévesque, Christian, Peter Fairbrother and Nicolas Roby (2020). Digitalization and Regulation of Work and Employment: Introduction. Relations industrielles/industrial relations 75(4): 647-659

- McKeown, Tui (2016). A consilience framework: Revealing hidden features of the independent contractor. Journal of Management and Organization 22 (6): 779-796.

- Meijerink, Jeroen and Martijn Arets (2020). Online labor platforms versus temp agencies: What are the differences? Strategic HR Revew. DOI 10.1108/SHR-12-2020-0098.

- Meijerink, Jeroen and Anne Keegan (2019). Conceptualizing human resource management in the gig economy. Journal of Managerial Psychology 34(4): 214-232.

- Nakatsu Robbie T., Elissa B. Grossman and Charalambos Iacovou (2014). A taxonomy of crowdsourcing based on task complexity. Journal of Information Science 40: 823-834.

- Nesheim Torstein. (2004). 20 år med Atkinson-modellen: Åtte teser om 'den fleksible bedrift'. Sosiologisk tidsskrift 12: 3-24.

- Nesheim Torstein, Bjørnar Fahle and Anita E. Tobiassen (2014). When external consultants work on internal projects: exploring managerial challenges. Management and organization of temporary agency work. Routledge, 84-98.

- NOU (2021). Den norske modellen og fremtidens arbeidsliv. NOU 2021: 9.

- Oliver, Christine (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes, Academy of Management Review 16: 145-179.

- Olsen, Karen M. (2006). The role of nonstandard workers in client-organizations. Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations 61(1), 93-117.

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey and James N. Baron (1988). Taking the workers back out: Recent trends in the structuring of employment. Research in Organizational Behavior 10: 257-303.

- Prassl, Jeremias (2018). Humans as a Service - The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy, London: Oxford University Press.

- Ratti, Luca (2016). Online Platforms and Crowdwork in Europe: a Two-Step Approach to Expanding Agency Work Provisions. Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, 28 (2): 477-511.

- Roverud, Liv Helene, Tor Kristian Kjølvik, Torstein Nesheim and Kristin Jesnes (2017). Mellomledd i oppdragsmarkedet. Søkelys på arbeidslivet 34: 199-215.

- Steen, Jørgen Ingerød, Johan Røed Steen, Kristin Jesnes and Rolf Røtnes (2019). The knowledge-intensive platform economy in the Nordic countries. Nordic Innovation.

- Vallas, Steven and Juliet B. Schor (2020). What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig Economy. Annual Review of Sociology 46: 273-294.

- Vallas, Steven (2019). Platform capitalism: What’s at stake for workers? New Labor Forum. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 48-59.

- Wang, Tianyu and Fang Cooke (2021). Internet Platform Employment in China: Legal Challenges and Implications for Gig Workers through the Lens of Court Decisions. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations 76(3): 541-564.

List of figures

Figure 1

Classification of Economic Work Arrangements (Cappelli and Keller, 2017: 577)

List of tables

Table 1

Functions of Labour Market Intermediaries

Table 2

Overview of Intermediaries and Functions

10.7202/1065173ar

10.7202/1065173ar