Abstracts

Keywords:

- set design,

- Atikamekw,

- Ondinnok,

- arts,

- theatre

Article body

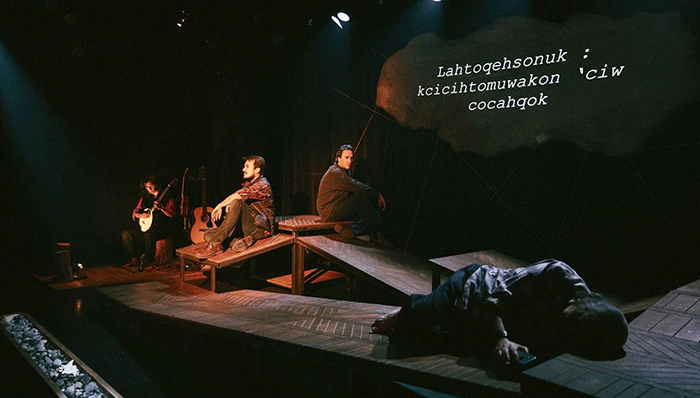

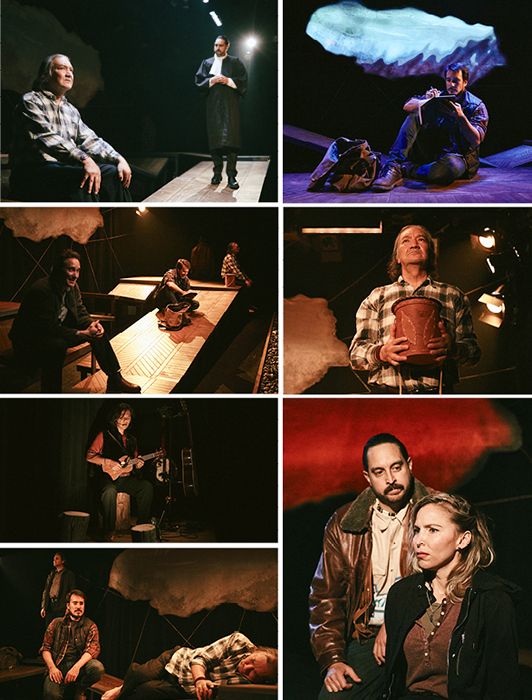

Nmihtaqs Sqotewamqol / La cendre de ses os, with Charles Bender, Nicolas Gendron, Roger Wylde, and Kyra Shaughnessy. Théâtre La Licorne, Montréal, 2021.

Julie-Christina Picher is a painter and the first Atikamekw set designer in Québec. She lives and creates in Sacré-Coeur-sur-le-Fjord-du-Saguenay on the Upper Côte-Nord. It seemed essential to present the work of Picher’s unique voice within the theatrical landscape in this thematic issue. Our conversation unfolded over the course of several months. The insights gathered here are the result of emails and Zoom exchanges in which the artist discussed the unique journey that has led her (since obtaining her diploma in set design from Collège Lionel-Groulx in 2011) to collaborate on over twenty theatrical productions (including six with Ondinnok Productions) as well as other cinematic projects.

Julie Burelle: Julie-Christina, you are a painter with a background in Fine Arts. How did you discover the profession of set designer?

Julie-Christina Picher: I started to take an interest in set design in 2005. I had just completed a program in Fine Arts at the Cégep de Saint-Jérôme. I had friends who had gone to study visual arts at Concordia. I, on the other hand, had decided to take a break to explore other art forms. I didn’t want to pursue visual arts; I found it, I don’t like the word, but individualistic? I wanted collaboration, exchange, to be part of a working team. So, I took a year to attend shows and exhibitions. But I knew I needed to go back to school because I didn’t want to be self-taught, and teamwork had always been at the heart of my approach.

I went to the Education Expo, and that’s where I saw the model and period costume from the National Theatre School. It was when I saw the booth, the technical plans, and the images of performances that I truly became aware of the existence of this profession and the schools that teach it. It’s as if when you’re an audience member, you don’t necessarily realize all the work behind the performance. All the credit generally goes to the actors and the director, but there are artists, artisans who work to make all of this possible.

J. B.: What led you to choose the program at Collège Lionel-Groulx?

J.-C. P.: The uniqueness of Collège Lionel-Groulx was that in the first year, we were exposed to everything. We learned about lighting, sewing, and visual arts. It was as much technical as it was design oriented. It was only later that we chose which area to specialize in for our diplomas. From the very first week, I felt like I was in the right place. We were told it would be challenging; there were about one hundred twenty people in the auditorium at the start of the program, and they told us, “In four years, there will be around thirty of you.” But I never second-guessed myself: I was where I needed to be.

At the end of my training, le Petit Théâtre du Nord offered me my first opportunity to work on a set design. I was in the midst of our year-end production, preparing for a trip to participate in the Prague Quadrennial in Set Design with my cohort. So, it was an addition to my already busy schedule, but that’s how the profession is: managing multiple projects and contracts simultaneously. This show, La grande sortie (2011) by Mélanie Maynard and Jonathan Racine, was later restaged at Théâtre du Rideau Vert in 2014 and toured across Québec. I was fortunate: it kick-started my career.

J. B.: Many of the contributors in this thematic issue reflect on their experiences within institutional theatres or training programs and identify structural and interpersonal obstacles they had to face. How about you? Was there room for your Atikamekw culture in your training?

J.-C. P.: In 2008, there was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) in Montréal. My mother participated as a volunteer. I went there for the conferences, sharing, and events. I understood a lot of things at that time. I questioned things, I questioned my mother... I had distanced myself a bit from some of my family members because I saw them spiraling, and I didn’t understand why, why they were in so much pain. My mother had talked to me a bit about the residential schools, but it was a taboo subject. There had been so much suffering. I didn’t fully understand her. It’s worth mentioning that I was also young. On my end, I had some really nice memories of my childhood with my grandparents in the woods, at the camp, but I also had some sadder memories... My pride was no longer there; it was extinguished. I was almost ashamed to say that I was Atikamekw, Indigenous, because, also, in elementary school, in high school... [silence] in short, I didn’t say it anymore. When I entered the drama school, I didn’t say it either.

But in 2008, there was the Commission, and at the same time, my brother took his own life. It was a difficult year. I did a lot of introspection related to myself, my family, who I was, where I was going. What had happened in the minds of my brother, my cousins, my uncles, who also took their own lives? The TRC allowed me to heal from something I didn’t even know I was carrying. I understood that there were people who were suffering even more than me, who had experienced unimaginable things. I used this anger I had towards some family members who had done difficult or hurtful things (addictions to alcohol, drugs, domestic violence, physical and mental abuse), and I started painting large canvases inspired by my culture. I did this separately, in my studio, at home. Inevitably, the art I was developing at home had an impact on what I was learning at school. This being said, it happened unconsciously: I subtly brought what I carried into my work. It showed in some things, but my teachers didn’t tell me to draw from my culture, that it was rich. I think they knew a little about what was happening with my brother. I had talked to them about the Commission and the fact that many people didn’t understand the residential schools, but like many, my teachers weren’t really aware, and I didn’t always want to talk about it.

I really regained my pride after leaving school. The TRC had effects. I evolved, my family did, too, people opened up. It was good for many people. I immersed myself more in my culture after leaving school. It’s in the art itself that I let everything out with the Kinokewin series. This series of paintings is quite dark. I needed to get it all out. I had initially made the paintings for myself, but a friend who is a gallery owner saw them and strongly encouraged me to exhibit them. He said, “They need to be seen!” I did the exhibition in a bar. I wasn’t doing it for money or to become known. I was happy to share with friends and strangers. But I was afraid afterward; I didn’t necessarily want to enter the big leagues. I have a friend who is well-known, and he didn’t paint the same way anymore because of the pressure he experienced. And then, I wanted to focus on theatre. Since the oil painting and lacquer I used were harmful, and I was pregnant, I put that aside. But it’s in my plans to dive back into it.

J. B.: You are a long-time collaborator of Ondinnok, which was for a long time the only Indigenous theatre company in Québec. Tell us about this relationship.

J.-C. P.: At the end of my studies, in my fourth year, I created costume models for the character of Perceval in a project for Clément Cazelais, a professor at Lionel-Groulx. It was very spiritual, very mythological, and I drew inspiration from a character who was an Indigenous chief because, to me, he was a proud, wise character who didn’t take sides and listened to everyone. I had already told Clément, “I am Métis, I am Atikamekw, my mother is Atikamekw.” My work had caught his attention, but that was it. Shortly after finishing school, I received an email from Clément, telling me that he was working for Ondinnok Productions, that he had mentioned me, and that the management was interested in meeting me.

I was already familiar with Ondinnok, having seen several of their shows, but I was too shy to approach them and say, “I’m a scenographer and I’m Atikamekw.” I thought to myself, “I need to work, stand out, and then I can come in with some material.” Eventually, I met the team, and we spent a whole afternoon talking. Yves Sioui Durand and Catherine Joncas told me about their upcoming project, and at the end of the meeting, they asked me, “Are you interested in doing the scenography for our Printemps autochtone d’Art at the Maison de la culture?” I jumped at the opportunity! I got involved, and we did several other productions together, including L’écorce de nos silences (2013), Tu É Moi (2013), Lola (2015), Mokatek et l’étoile disparue (2016, 2017-2018), and Nmihtaqs Sqotewamqol / La cendre de ses os (2019-2020).

Nmihtaqs Sqotewamqol / La cendre de ses os, with Charles Bender, Nicolas Desfossés, Nicolas Gendron, Marilyn Provost and Roger Wylde. Théâtre La Licorne, Montréal, 2021.

J. B.: What is unique or different about working with Ondinnok and creating intercultural Indigenous theatre with their team?

J.-C. P.: In my work, I enjoy brainstorming with others. I really need to have a team around me that brings its ideas, to be nourished by the director and the person who wrote the text, the author. The final work is very important, but it’s the process that excites me. That’s why I like to surround myself with creative, inspiring people who have experience, often fifteen or twenty years of experience. Ondinnok is a company that has been around for a long time, and they’ve done incredible, groundbreaking, original, and very daring productions. What intrigues me the most is the way Yves and Catherine think and bring ideas to the table.

In terms of scenography, there is a direct connection to my culture when I work with Ondinnok. I think differently, I approach things differently, I refer to memories, photos, anecdotes. There’s also the aspect of intercultural exchanges. In the creative process, I explore what I don’t know. For example, the Huron-Wendat, what was it like for them? I’m always learning... There’s a sharing of First Nations cultures that you don’t see elsewhere.

With Ondinnok, we really start from Indigenous cultures, and we speak the real, unfiltered truth: both the positive and the negative. We’re not afraid to have these discussions amongst ourselves. In other non-Indigenous theatres, there’s often a sense of walking on eggshells, and that’s understandable. There’s curiosity and even goodwill, but there might be a fear of appropriation. With Ondinnok, everything, from scenography to direction, acting, makeup, costumes, is inspired by the team, the individuals, their originality and the darkness that exists within all of us. There’s this great open-mindedness, but there’s also, how should I put it... we’re not trying to create a product, and the primary focus is on the collective process. Every theatre has its signature, and what strikes me about Ondinnok is the complete trust they place in the artists they invite. They provide a blank canvas and say, “Propose, and we’ll rally around it!” Each production is a world shaped by the artists invited to create. There’s total freedom, and there’s a profoundly human approach. There’s no pretension. I’ve had moments where I’ve burst into tears in meetings because things weren’t going well in my life, and there’s room for that. I can arrive with my two-year-old child, who’ll run around the rehearsal space, pick up a drum, ask me questions, and that’s how it is – it’s like a family. There’s something very human about it, and that remains even after Yves and Catherine’s retirement.

J. B.: I had the pleasure of seeing Mokatek, an Ondinnok production for young audiences, written and performed by Dave Jenniss, who became the artistic director of Ondinnok after the departure of Yves Sioui Durand and Catherine Joncas. This was in Ottawa in May 2018. For the show, you created a tent for the little ones (aged two to six) and their caregivers, and an intimate and magical atmosphere that took me back to my childhood...

J.-C. P.: For Mokatek, I wanted the shape of a Shaputuan (the long Innu tent). The romantic side of me would have liked the structure to be made of wood, but I already knew there would be a tour, that we would be in all sorts of venues, with only four hours for setup. It had to be quick. That was the initial constraint.

On top of this, our audience would consist of children. So, it had to be very safe. It was a technical challenge that my partner greatly helped me to overcome! For the tent structure, we contacted a company that made tunnel greenhouses near Drummondville. Then we tested some options at our place in the Côte-Nord, we had pieces fabricated so the structure could be anchored to the ground. I was the technical director throughout the creative process because my design stemmed from it.

The fabric of the tent posed another technical challenge. I wanted to capture the spirit of a child’s blanket fort made in the living room with bed sheets, a magical and organic place. So, we set up the structures we envisioned in Ondinnok’s rehearsal space in the Côte-Nord, and I installed all the fabrics myself. From one setup to another, some fabrics could be hung differently, while others had to remain in the same place for the lighting.

In our technical plans, everything was smaller. The audience setup was different: we counted in terms of places for children, with space for parents or educators in the back. We brainstormed a lot, but the process was so interesting! I felt like a child building a giant fort. Then, when the children entered the space, we saw that it worked. As a scenographer, I felt that my team and I had the time and space to explore because we were working with Ondinnok. I might not have had the same freedom to explore if the mandate had come from another company.

Mokatek et l’étoile disparue, with Dave Jenniss and Élise Boucher-DeGonzague. On tour, Québec, 2018.

J. B.: We talk about engagement and creation protocols established by Indigenous artists in this thematic issue. What aspects of Ondinnok’s theatre (their protocols and ways of engaging and creating) would you like to see institutional theatres adopt?

J.-C. P.: The relationship with family, the human aspect of it. People should consider, not only in theatre but in all forms of work, the human being, making sure there’s room for someone who might be running late or going through a tough time... I hope we don’t overlook the human side of our collaborators but instead incorporate that dimension into the process. At Ondinnok, people are more sensitive to this. There is room for sharing, there is a sensitivity when someone is struggling. There is compassion. We ask human questions before starting a meeting. We should be inviting the person in their entirety into a creative process and not just their professional skills.

There are sharing rituals at Ondinnok. Before each performance, for example, there’s a ritual involving sage. Of course, the idea isn’t for all theatres to start burning sage, but what rituals could be developed to signal to artists that the invitation is all-encompassing, that “you don’t have to show up with just your professional contributions, you can come as you are, in your entirety”?

At Ondinnok, the work is also done in a more instinctive manner. They work with people who don’t always have extensive experience, who don’t necessarily have fifteen years of work under their belt. This can create a lot of insecurity and fear at times, but Ondinnok has developed an approach that allows people to enter the creative process with self-confidence. Ondinnok’s theatre is more accessible to people who haven’t received formal training but have the desire to engage in performing arts. In institutional theatres, there are established methods, rules, and approaches, and they certainly have their place. There are wonderful productions in institutional theatres, but Ondinnok makes it more accessible to Indigenous artists. Ondinnok has trained many young artists on the job.

J. B.: You are the first Atikamekw set designer in Québec. You are part of a growing, albeit still limited, number of Indigenous artists working professionally in Québec. How can we nurture the next generation?

J.-C. P.: I am the only Atikamekw set designer in Québec, and we need to nurture the next generation. This is something that resonates with me deeply. There’s a lack of Indigenous representation in set design. I genuinely believe that anyone working in visual arts, whether they’re a painter, sculptor, costume designer, can develop an interest in set design and enter this field with some coaching and brief training. Telling these artists to pursue a full four-year program can be a barrier. It’s too much. Even I found it challenging. Leaving one’s community and family to work seventy hours a week in a program that isn’t very lucrative if you’re only getting small contracts might not be appealing. But coaching and shorter training? That’s something that interests me, and I believe it would be a better fit. In the long term, I have a project for an artist residency with an integrated workshop here, in my home. I would invite artists to create on-site and offer short programs and training. I’m located near Tadoussac, in Sacré-Coeur.

J. B.: You also work in the field of independent cinema, most notably through collaborations with filmmaker François Delisle, and more recently with Chloé Leriche, for whom you did your first art direction for Soleils Atikamekw (2023), a feature film shot in 2021. Tell me about your journey in this area.

J.-C. P.: Chloé Leriche’s Soleils Atikamekw is currently in the editing phase, and it’s going to be beautiful. Regarding cinema, I’ve been offered artistic direction roles, but the time away from my family is challenging. I might wait until my children have grown a bit more. In the meantime, I’m focusing on projects that enrich us, not only financially but also intellectually and emotionally. My children, my mother, my family, and my friends are at the heart of my plans for the coming year.

J. B.: Thank you, Julie-Christina, for so generously offering your time and insights. Thank you for accepting the invitation that Jill and I extended to you!

Appendices

Biographical note

Julie Burelle is a professor of Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of California, San Diego where she also teaches in the minor in Native American and Indigenous Studies. She is the author of Encounters on Contested Lands: Indigenous Performances of Nationhood and Sovereignty in Québec (Northwestern University Press, 2019) translated in French and published by Nota bene in 2022. She has co-authored with Yves Sioui Durand, Catherine Joncas and Jean-François Côté Xajoj Tun. Le Rabinal Achi d’Ondinnok : entretiens, réflexions, analyses (PUL, 2021). Her work has appeared in Liberté, Jeu, TheatreForum, TDR: The Drama Review, Dance Research Journal and other journals. She also is a dramaturg.