Abstracts

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate whether career competencies could enhance young professionals’ perceived employability via job crafting and career success. 1008 respondents answered an online survey with 957 valid answers. Partial least square structural equation modeling was used and the results of the study were significant. First, career competencies directly affect perceived internal and external employability with the stronger effect on the latter. Second, career success partially mediates the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability. Third, job crafting partially mediates the relationship between career competencies and perceived employability. The study extends the previous literature on employability to a personal perspective with the effects of personal resources through personal adaptation and success leading to HR management indications.

Keywords:

- Career Competencies,

- Perceived Employability,

- Career Success,

- Young Professionals,

- Job Crafting,

- Vietnam

Résumé

Cette étude visait à déterminer si les compétences professionnelles pouvaient améliorer l’employabilité des jeunes professionnels via la création d’emplois et la réussite professionnelle. Parmi 1008 réponses d’un sondage en ligne, 957 sont valides. Avec la modélisation de l’équation structurelle des moindres carrés partiels, les résultats ont été significatifs. Premièrement, les compétences professionnelles affectent directement l’employabilité interne et particulièrement celle externe. Deuxièmement, la réussite professionnelle médiatise en partie la relation entre les compétences professionnelles et l’employabilité interne perçue. Troisièmement, le job crafting médiatise en partie la relation entre les compétences professionnelles et l’employabilité. L’étude étend la littérature antérieure sur l’employabilité à une perspective personnelle avec les effets des ressources personnelles à travers l’adaptation et la réussite personnelles menant à des recommandations de gestion des RH.

Mots-clés :

- Compétences professionnelles,

- Employabilité perçue,

- Réussite professionnelle,

- Jeunes Actifs,

- Job Crafting,

- Vietnam

Resumen

Este estudio tiene como objetivo determinar si las habilidades profesionales podrían mejorar la empleabilidad de los jóvenes profesionales a través de la creación de empleo y el éxito profesional. Con el modelo de ecuaciones estructurales de mínimos cuadrados parciales, los resultados son significativos: las habilidades profesionales afectan directamente la empleabilidad interna y externa percibida, con un mayor impacto en la segunda; el éxito laboral media parcialmente la relación entre las habilidades laborales y la empleabilidad interna percibida; y la creación de puestos de trabajo media parcialmente la relación entre las habilidades profesionales y la empleabilidad. El estudio amplía la literatura previa a una perspectiva personal a través del ajuste personal y el logro que conduce a recomendaciones de gestión de RR.HH.

Palabras clave:

- Competencias profesionales,

- Empleabilidad Percibida,

- Éxito Profesional,

- Jóvenes Profesionales,

- Elaboración de Trabajos,

- Vietnam

Article body

Employability and its significance

Research on employability has drawn attention from scholars for nearly a century due to its complex nature. One of the first articles about employability was published in 1927. It identified the need for achievement as the determinant of employability (Tseng, 1972). Having developed over nearly 100 years, the nature of employability has been considered complicated (Sumanasiri et al., 2015) because employability can be investigated through many perspectives: employers, educators, students or even policy-makers (Rothwell & Rothwell, 2017). Similarly, this issue is also investigated in different approaches and themes, such as capital, career management, and contextual approaches (Williams et al., 2016), within different contexts (Van der Heijde, 2014).

Moreover, employability has become a global norm and the priority for policy actors. In detail, policy actors have been encouraged to change education policies, especially when there have been global skill mismatches or large-scale unemployment (Singh & Ehlers, 2020). One of the main reasons for these weaknesses is from a structural shift in labor markets and the resulting gaps between what employers require and what undergraduates and graduates possess. For example, identified skill gaps are critical thinking, interpersonal skills, self-management, communication, and problem-solving (Abbasi et al., 2018) or numeracy, independent learning, IT, and creativity (Hill et al., 2019). More generally, graduates have hardly met soft skill requirements at work (Succi & Canovi, 2020).

Therefore, improving employability is drawing attention from recruiters, higher education institutions and employees, not only globally but also in the Vietnamese context. Vietnam is one of seven Asian Pacific countries facing challenges in attracting and retaining employees with desired qualifications, skills and capabilities (Prikshat et al., 2016) with a weak transition from education to work (Cameron et al., 2017). On the one hand, Vietnamese higher education institutions (HEIs) are claimed to be weak at doing their tasks of training industry-ready workforces, resulting in an oversupply of poorly trained graduates (Thang & Wongsurawat, 2016). On the other hand, employers tend to require many skills and abilities because they require more than just job-specific skills (Tran, 2015). One of the biggest challenges that graduates face is finding a way to improve their soft skills (Nghia et al., 2019). Therefore, there are calls for cooperation between HEIs and companies to improve the employability of graduates and a call for an HRM approach reflecting Vietnam’s contextual values (Nguyen et al., 2018). Hence, the need for a comprehensive investigation of employability issues in the Vietnamese context has been obvious.

Though the literature illustrates a rapid growth in employability research in the literature, the focus of studies on employability has been mainly the preparation of higher education institutions (HEIs). The review of Masduki et al. (2022) reveals that there has been a rapid growth in employability research and predicts that there will be more and more research in the field. A variety of studies in the literature devoted to finding out what HEIs did and should do to equip graduates with employability skills (Ressia & Shaw, 2022). These investigations have been related to skill gaps, out-come based learning, work-integrated learning, extracurricular activities, internship etc., (Noori & Azmi, 2021). These studies highlighted the role of HEIs in enhancing graduates’ employability with the gaps between HEIs’ preparation and employers’ requirements (Tran, 2015, Chhinzer & Russo, 2017) such as weak soft skills, overeducation, and job mismatches (Figueiredo et al., 2017, Hill et al., 2019).

Besides, a host of other studies regarded graduate employability as employees’ assets such as career attitude, social capital and emotional intelligence (Forrier et al., 2018). These focuses treat employability as a result rather than a process. Therefore, the focus on personal agency in employability research is still considered an overlooked side of employability (Forrier et al., 2018). Similarly, Dinh et al., (2022) has recently called for a more comprehensive research focusing on personal agency and employability in certain contexts and relationships.

Employability and personal agency

Putting personal agency at the heart of employability research allows researchers to regard employability as a process in human resources management (HRM) rather than a result of education. From personal perspective, employability involves both external and internal employability, which involves not only graduates’ preparing and obtaining a job (Ressia & Shaw, 2022), but also their maintaining, developing jobs. The heavy focus of the literature on employer’s requirements and HEIs’ preparation concerns HEIs’ roles rather than individuals themselves in improving graduates’ employability. In contrast, an investigation from a personal agency enables researchers to have a more comprehensive framework to understand graduates’ employability. “Competence-based approaches define employability as a multi-dimensional process that is in development over time” (Römgens et al., 2020, p.2590) and identifying competences at an individual level is vital to help employees both obtain and retain a job in such a highly competitive labor market.

Therefore, the literature reveals that the focus on employers’ and HEIs’ perspectives needs to be supplemented by a personal perspective. One of the very important personal resources of employees is career competencies (reflective, communicative and behavioral elements), which are related to early career success and job crafting, resulting in higher employability (Bargsted et al., 2021). Career competencies consist of knowledge, skills and ability to develop career development, influenced and developed by individuals (Akkermans et al., 2013) and are positively related to early career success (Presti et al., 2021). Career competencies are the basis for graduates to utilize their personal qualities and motivations in the transition to jobs, which is considered the first step for young professionals to achieve their early career success (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012).

Regarding personal resources, career competencies can pave the way for graduates to take the initiative to enhance their self-perceived employability (Rothwell et al., 2009). Strong career competencies enable graduates to learn and adapt to their working environment, which is vital in their transition to work (Kuijpers et al., 2006). In addition, job crafting (task crafting, relation crafting and cognition crafting) is the act of individuals shaping their jobs to match their preferences, skills, and abilities (Berg & Dutton, 2008). According to Muhammad & Qadeer (2020), one of the important predictors of perceived employability is the willingness to make changes in jobs. More specifically, adjusting jobs according to individual needs enables employees to maintain and better their performance, leading to an improvement in their internal employability (Muhammad Irfan & Qadeer, 2020). In addition, an increase in task crafting was proven to be related to employees’ perceived external employability (Plomp et al., 2019). Therefore, career competencies have been improved to promote changes in job crafting, leading to better employability as a center outcome (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

Research Significance

A close investigation into the role of job crafting and career success and job crafting in the relationship between career competencies and perceived employability among young professionals in Vietnam is critical for the following reasons. Firstly, in the literature, a few studies which have been done by some key names Nghia et al., (2019), Tran (2015), and Thang & Wongsurawat (2016) focus on employability skills. In these studies, serious concerns about weak employability skills such as soft skills, loose connections between universities and companies, unrealistic curricula, etc. have been pointed out. These issues are considered reasons for hindering graduates from achieving success. However, in the Vietnamese context, there has been limited research on career competencies as well as its effects on career success, which makes it worth looking into the mediating role of career success. Secondly, Sartori (et al., 2022) has proposed job crafting as intervention at work to improve employees’ employability and called for research to explore the role of changing job resources and challenges in enhancing employability. Thirdly, there has been a rise in the turnover rate among young professionals in the 9x generation in 2019 (Haymora, 2019).

Research questions

This study aims to answer the following research question: “To what extent do job crafting and career success affect the relationship between career competencies and perceived employability among young professionals in Vietnam?” We propose a mediation model in which the level of employability that young professionals can develop depends on their career competencies, mediated by career success and job crafting. This study contributes to the literature on employability by filling two theoretical gaps. First, it contributes to the scholarly debate on antecedents/predictors of young professionals’ employability by examining the role of career competencies in achieving career success and job crafting and subsequently perceived employability. Second, it extends the previous literature on employability to a more personal perspective, which can lead to HR management indications and practices.

Theoretical framework

Employability definition and three main perspectives

Despite various interpretations of employability, it is understood as graduates’ ability to gain and maintain their occupation and become successful in present and future employment opportunities. Employability is defined as knowledge, skills, and attributes that are presented and used in and contexts (Hillage & Pollard, 1998). In addition, Sanders & De Grip (2004) defined employability as employees’ willingness and capacity to predict changes in their tasks, the working environment and reacting proactively to these changes. According to Yorke (2006), employability is “a set of achievements – skills, understandings and personal attributes – that makes graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations” (p. 8). A shorter definition was proposed by Hogan et al., (2013), with employability being the ability to gain and retain employment.

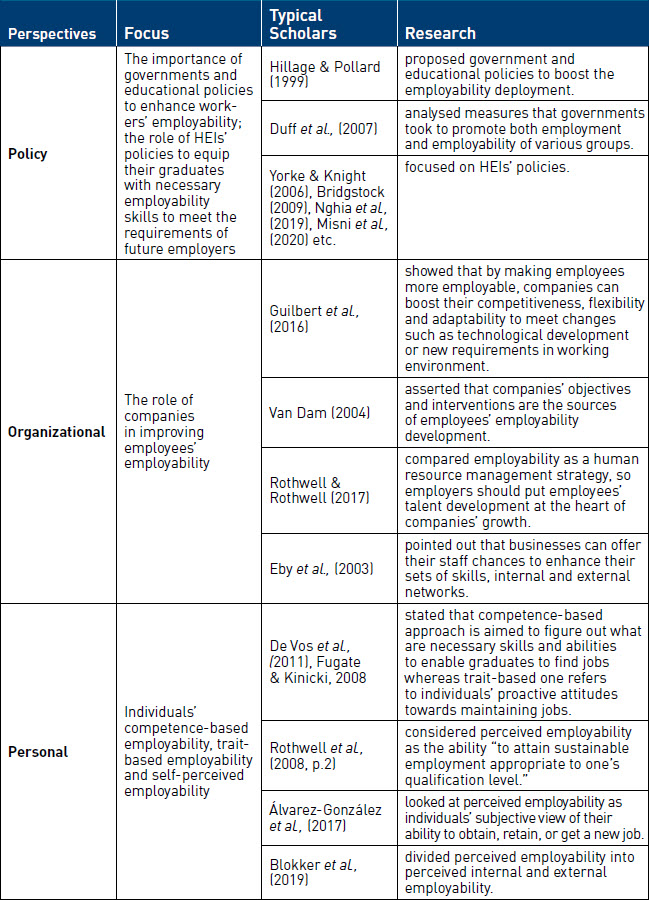

Employability has been mainly investigated through three perspectives: policy, organizational and personal perspectives [See Table I]. While the organizational perspective focuses on employers’ strategies to boost employees’ employability, policy perspective emphasizes the contribution of curricula to graduates’ employability as well as job creation and sustainability (Guilbert et al., 2016). The personal perspective includes 3 approaches: competence-based employability, trait-based employability and self-perceived employability (Vargas et al., 2018). Perceived employability is an effective approach because it “focuses on just on internal personal factors related to one’s perception of one’s own capacities and skills for finding a job, but also on structural or external factors, such as the individual’s perception of the impact of the external employment market and the importance of their qualifications or profession when trying to find a job.” (Vargas et al., 2018, p. 3). Accordingly, perceived employability is divided into perceived internal employability and perceived external employability (Blokker et al., 2019). More specifically, “external employability refers to the ability and willingness to switch to a similar or another job in another firm…Meanwhile, internal employability refers to a worker’s ability and willingness to remain employed with the current employer…” (Juhdi et al., 2010, p. 2).

Employability in Vietnamese Context

In the Vietnamese context, some key authors are conducting research into undergraduates’ and new graduates’ employability with a focus on HEIs’ preparation and employers’ requirements, followed by solutions. Tran Le Huu Nghia published a series of articles looking into graduates’ and final-year students’ skill gaps and the role of extracurricular activities and external stakeholders in building graduates’ soft skills and enhancing graduates’ employability (Nghia et al., 2019). Similarly, Yao & Tuliao (2019) also confirmed the important role of soft skills that students were taught at transnational universities in Vietnam in improving their graduate employability. Additionally, Nghia et al. (2019) carried out interviews with third—and fourth-year students and pointed out gaps between students’ employability and employment outcomes. In addition, in several articles, Tran Thi Tuyet pointed out graduates’ lack of employability skills due to loose collaboration between enterprises and universities in enhancing employability (Tran, 2015). For the IT sector, Thang & Wongsurawat (2016) pointed out the skill weaknesses of graduates in the IT industry in Vietnam and proposed solutions.

Regarding the Vietnamese labor market, employability, especially perceived employability, has gained increasing significance among young professionals. First, it is because “employment is a real outcome of perceived employability” (Thang & Wongsurawat, 2016, p. 148). As a result, skill mismatch exists in the Vietnamese economy, leading to an increase in the number of graduates who failed to obtain a job in accordance with their qualifications (Tong, 2019). Second, there has been a rise in the turnover rate among the 9x generation, especially in marketing, sales, IT and finance, with a rate of 24%, far away from the ideal rate of 10% (Vietnamnews.net, 2019). Moreover, the average rate of turnover in Vietnam in 2019 was 24% (Adecco, 2020), which is much higher than the recommended rate of 10% (Haymora, 2019). Surprisingly, 17% of this rate belonged to young professionals in the 9x generation in 2019 (Haymora, 2019). Furthermore, the unemployment rate in Vietnam has been the highest over the last five years (Vietnamplus.vn, 2020).

Table I

Three Perspectives in Employability Research

Hypothesis Development

Career competencies as an antecedent of perceived employability

The term “career competencies” was defined in Akkermans et al. (2013) study, “career competencies concern knowledge, skills, and abilities which can be influenced and developed by the individual” (p. 249) with three dimensions of reflective, communicative and behavioral career competencies. First, reflective career competencies concentrate on individuals’ awareness of their longstanding careers and their personal reflections on motivation and qualities concerning their professional careers. Accordingly, reflections on motivation and qualities involve reflecting on values, passions, motivations, strengths, shortcomings, and skills. Second, communicative career competencies are the ability to communicate with important people to enhance individuals’ chance of success by networking and self-profiling. While networking refers to building and expanding a network for career-related aims, self-profiling indicates showing and communicating knowledge, abilities and skills to both internal and external markets. Third, behavioral career competencies relate to work exploration and career control. The former being defined as active exploration and search for work-related and career-related changes in external and internal markets. The latter being defined as actively setting goals and planning how to achieve goals in learning and working. Communicative career competencies and behavioral competencies are pointed out as two important factors by Dumulescu et al. (2015).

Blokker et al. (2019) concluded that a higher level of career competencies leads to a higher perceived employability among young professionals. Career competencies enable graduates to search for more opportunities in the labor market and obtain better control of their career, which results in higher perceived employability (Forrier et al., 2015). The positive relationship between career competencies and perceived employability (both internal and external) was also confirmed in the research of Akkermans & Tims (2017). Moreover, career control can help improve perceived employability opportunities, such as making more efforts to overcome difficulties or attain personal goals, thus improving perceived employability (Bargsted, 2017). Three of four important employability components are general competencies, professional competencies, and career planning and confidence. As a result, the enhancement of these features also leads to improving graduates’ employability (Chen et al., 2018). Based on these findings, we hypothesize the following:

H1: Vietnamese young professionals’ career competencies are positively related to their perceived internal employability.

H2: Vietnamese young professionals’ career competencies are positively related to their perceived external employability.

Career competencies and perceived employability: the mediating roles of career success

In the literature, career success was long identified as “the positive psychological or work-related outcomes or achievements one has accumulated as a result of one’s work experiences.”(Judge, et al., 1995, p. 486). This definition coincides with the definitions of the other authors, such as London & Stumpf (1982) and Seibert et al., (1999). Based on this definition, career success emphasizes “the attained career accomplishments through work experiences” (Niu et al.,2019, p. 3).

Career competencies directly impacted career success in terms of career satisfaction (Kong et al., 2012). The action of realizing personal goals helps increase objective career success because the fulfillment of goals will be mirrored in a pay rise and a high occupational status. Moreover, reflecting on one’s career competencies such as motivation and quality results in a realistic image of one’s capabilities so that one can choose a career that is suitable for their existing capabilities. Career control, especially learning goal orientation and networking, is closely related to career satisfaction (Kuijpers et al., 2006). In addition, career competencies have been proven to have effects on career success in one recent study conducted by Ahmad et al., (2019). According to Blokker et al. (2019), career competencies affect both subjective career success and objective career success, but the impacts on the former are stronger than those on the latter. Similarly, in the Career Construction Theory, Savickas (2005) described career competencies as an important component of adaptability facilitating employees in “fitting themselves to work that suits them” (p.45), which can lead to career success at work.

Moreover, employability is understood as the ability to obtain and maintain formal employment or find new employment when necessary. Admittedly, the causes for unemployment are “often attributed to economic factors, but psychological factors associated with employability also contribute to the problem” (Hogan et al., 2013, p. 3). Several recent studies have also concluded that there is a positive correlation between subjective career success and employability. One of the latest studies of Niu et al. (2019) confirmed that “subjective career success is positively correlated with perceived employability, especially in terms of internal employability” (p. 12).

Based on these findings and on Career Construction Theory of Savickas (2005) with the focus on career competencies in achieving career success, we argue that highly competent graduates will perceive themselves as more employable by witnessing more career success. Moreover, in previous studies, career competencies have been proven to have direct impacts on perceived employability (Forrier et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2018, Bargsted, 2017, Akkermans & Tims, 2017) and career success has also been proven to be a partial mediator (Bargsted et al., 2021); therefore, we test a partial mediation with the hypotheses as follows:

H3: Young professionals’ subjective career success partially mediates the relationship between graduates’ career competencies and their internal perceived employability.

H4: Young professionals’ subjective career success partially mediates the relationship between graduates’ career competencies and their external perceived employability.

H5: Young professionals’ objective career success partially mediates the relationship between graduates’ career competencies and their internal perceived employability.

H6: Young professionals’ objective career success partially mediates the relationship between graduates’ career competencies and their external perceived employability.

Career competencies and perceived employability: the mediating roles of job crafting

Job crafting is defined as “the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task or relational boundaries of their work” and “crafting a job involves shaping the task boundaries of the job (either physically or cognitively), the relational boundaries of the job, or both’’ (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001, p. 179). These changes involve both physical and cognitive changes in which the former changes are associated with tasks and relationships. and the latter changes are associated with the way individuals view their jobs (Lazazzara et al.,2020). Meanwhile, Tims et al. (2012) offered another definition of job crafting as “the self-initiated changes that employees make in their job and job resources to attain and/or optimize their personal (work) goals’’ (p. 173). This definition is based on the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., 2001, Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Job crafting is accordingly regarded as changes in which individuals make their job demands and their job resources balanced with their personal needs and abilities (Tims & Bakker, 2010). As a result, job crafting is individuals’ shaping of a job based on their own preferences, skills and abilities (Berg & Dutton, 2008).

In the JD-R theory of Bakker & Demerouti (2014), crafting is considered part of a motivational process in which personal resources have the potential to enhance job characteristics. From that, it can be argued that career competencies (personal resources) can promote changes in job crafting (job characteristics) and lead to a motivational process within which perceived employability is one of the central outcomes (Akkermans & Tims, 2017). More specifically, job resources can bring certain changes, such as task variety or autonomy, to employees and lead to them becoming more employable. When job resources promote employees to develop and improve their adaptability, these resources also play a vital role in boosting individuals’ perceptions of employability (Van Emmerik et al., 2012). According to Tims et al., (2012), challenging job demands, along with increasing job resources, can lead to expansive jobs, which stimulates personal growth and adaptability.

Consequently, employees’ feelings of being more flexible in the current organization and being more attractive to external labor markets (internal and external employability) are increased. Based on this and the argument from the JD-R perspective, we argue that graduates’ career competencies can set off a motivational process through job crafting, which finally develops their perceived employability. Job crafting as a partial mediator has been proven because crafting jobs can help employees turn their personal resources (career competencies) into their perceptions of being employable (perceived employability) (Akkermans & Tims, 2017), so we hypothesize the following:

H7: Graduates’ job crafting partially mediates the relationship between graduates’ career competencies and their internal perceived employability.

H8: Graduates’ job crafting partially mediates the relationship between graduates’ career competencies and their external perceived employability.

All hypotheses outlined above are visually represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

An illustration of the hypothesized relationship (H. hyphothesis)

Methods

Sample and procedure

The questionnaire was posted online in Alumni Facebook Groups of different Vietnamese universities, including Foreign Trade University, National Economics University, Trade Union University, Hanoi Architecture University, Posts and Telecommunications Institute of Technology, Hanoi University of Technology, Banking Academy, Dai Nam University, Thang Long University, Open University, Hanoi University, Vietnam National University, Thuong Mai University, Hanoi University of Natural Resources and Environment, and Hanoi National University of Education. In total, 1008 participants completed the online form. Because the study is primarily focused on the perceived employability of young professionals, only those working full-time in companies and organizations and who are within the age range of 23 to 30 years old are included. A total of 1008 responses were collected, and 51 responses were rejected because respondents were either students or not working. Finally, 957 were selected, with 261 males (27.27%) and 696 females (72.73%). According to some researchers, women have a greater tendency to take part in online activities for communicating and exchanging information, while their male counterparts have a greater tendency to do so for seeking information (Jackson et al., 2001). As a result, it is reasonable that the rate of female respondents is higher than that of male respondents because accessing an online survey, completing it, and returning it is more a process of online information exchange (Smith, 2008).

Measures

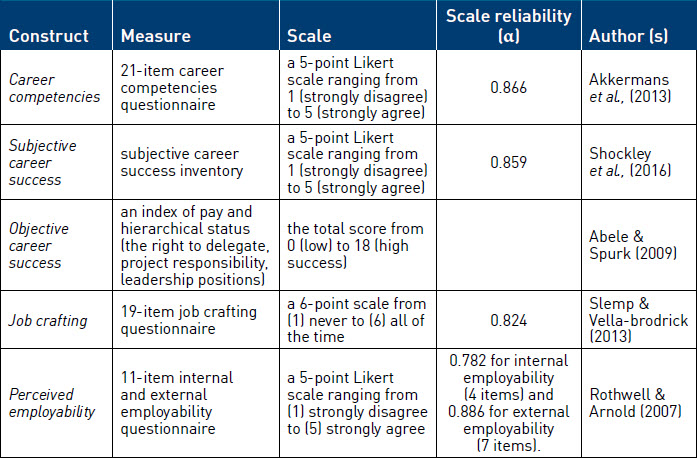

The questionnaire was administered in Vietnam and included two main parts, namely, demographic information and main questions. Below is the summary of the constructs, measures, and the authors of the related studies:

Table II

Constructs and Measurement Scale

The questionnaire was sent to HR managers and HR researchers for improvement and modification. A pilot test with the 400 samples was carried out first, and then the test with full sample data (n=957) was carried out.

Control variables. Gender (0 = male, 1 = female), age and year of experience were controlled.

Analysis

SPSS was used to provide the descriptive and correlational statistics, and partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to evaluate the measurement and structural models concerning the study variables and their associations. PLS-SEM is chosen for the study because the model contains higher-order variables and lower-order variables (hierarchical model) (Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, the study is aimed at identifying factors predicting graduates’ perceived employability, so PLS-SEM is a better choice for a prediction orientation analysis (Urbach & Ahlemann, 2010).

Regarding the measurement model, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability), convergent validity (AVE—average variance extracted) and discriminant validity are used for both higher-order constructs and lower-order constructs (Hair et al., 2017). These data were taken from both first-order reflective measurement models and high-order reflective measurement model evaluations. With a structural model, in addition to RMStheta (model fit measure), VIF values, P values, and R squares are used for collinearity assessment, path coefficients, coefficients of determination, and mediating effects (Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, common method bias (CMB) is identified with a full collinearity assessment approach (Kock, 2015). Apart from the direct effects, the study also aims to test indirect effects or mediating effects in Hypothesis with a bootstrapping method.

Results

The means, standard deviations and correlations among key variables from the first stage of data analysis are shown in Table III.

Table III

Means, Standard deviations, and Correlations Among Study Variables (N=957)

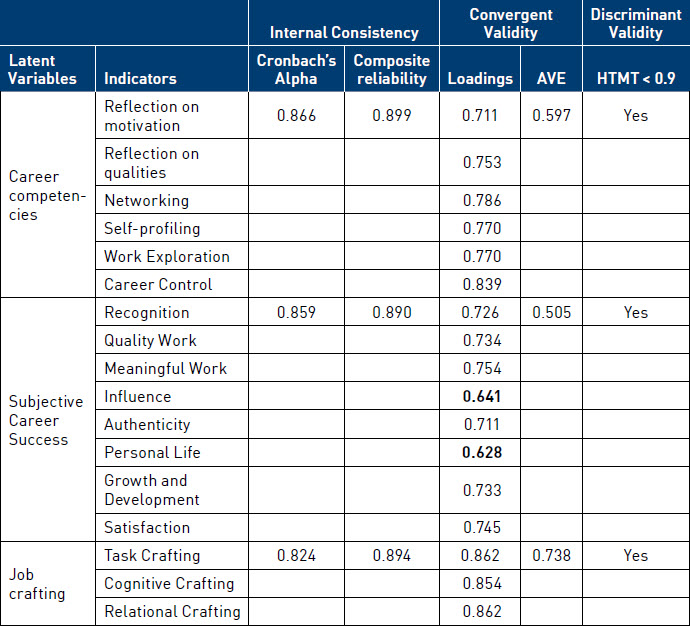

Before testing the research hypotheses, we conducted measurement model evaluation (with both first-order and higher-order reflective measurement models) and structural model evaluation [See Table IV and Table V]. For the measurement model, the values for internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability), convergent validity (indicator reliability-outer loadings of the indicators), average variance extracted (AVE) and discriminant validity (heterotrait-monotrait HTMT ratios) were all within the threshold values. The α values of the first-order and higher-order constructs ranged from 0.713 to 0.902 and above 0.8, respectively, indicating a good scale (Garson, 2016). Composite reliability values for all constructs were over 0.8 and regarded as satisfactory. All AVE values were greater than 0.5, so the indicators and constructs with loadings values under 0.7 were all maintained in the model (Hair et al., 2017).

Table IV

Measurement Model Evaluation (higher-order construct)

A lack of discriminant validity is better detected by the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Henseler et al., 2015), so HTMT values were calculated. All the HTMT values met the standardized requirement of the stringent cutoff of 0.85, showing that the model is well fitted (Kline, 2015) [See Table VI].

Table V

Measuremet Model Evaluation (lower-order construct)

Table VI

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

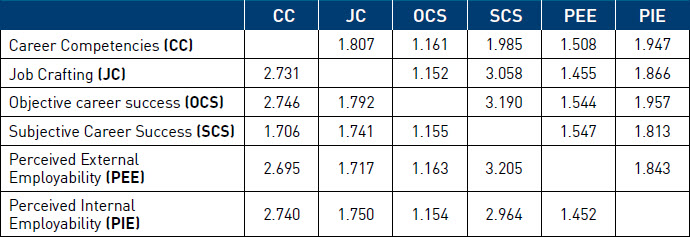

For the structural model, the measure fit model, VIF and coefficients of determination were tested. The RMStheta value of 0.103 below 0.12 indicates a well-fitting model (Hair et al., 2014). All the VIF values for latent variables are under 5, indicating no collinearity problem (Hair et al., 2011). All the R2 values range from 0.096 to 0.617, indicating that all the latent variables are explained by the others in the model. In addition, common method bias (CMB) is identified with a full collinearity assessment approach (Kock, 2015). All the VIF values are under 3.3, showing that the model used in this research is not affected by CMB (Hair et al., 2021) [See Table VII].

Table VII

VIF Values - Common Method Bias (CMB)

Hypothesis Testing

Regarding hypothesized relationships, career competencies were positively related to both perceived internal employability (β=0.116*, p<0.05) and external employability (β=0.22**, p<0.01), supporting H1 and H2. However, career competencies have stronger positive effects on perceived external employability than on perceived internal employability.

Table VIII

Hypothesis Testing

** correlation is significant at 0.01 level (P value <0.01)

* correlation is significant at 0.05 level (P value <0.05)

As illustrated in Table VIII, subjective career success partially mediated the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability with the indirect effect of 0.290** and the total effect of 0.55, supporting H3. However, subjective career success did not mediate the role between career competencies and perceived external employability. Although career competencies had a direct effect on perceived external employability with 0.22**, the indirect effect was not significant because subjective career success did not affect perceived external employability, leading to the conclusion that H4 was rejected. H5 was accepted because objective career success partially mediated the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability with the indirect effect of 0.012* and the total effect of 0.13. In contrast, H6 was rejected because the indirect effect was not significant because objective career success did not affect perceived internal employability. H7 and H8 were supported. Job crafting partially mediated the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability with the direct effect of 0.116* and an indirect effect of 0.140**. Moreover, job crafting partially mediated the relationship between career competencies and perceived external employability with a direct effect of 0.220** and an indirect effect of 0.176**. Additionally, the total effect of the latter was higher than that of the former (β = 0.40 vs. β = 0.26).

Discussion

The main aim of the study was to investigate the role of career competencies in achieving career success and job crafting and, subsequently, perceived employability among a group of young professionals.

As expected, career competencies directly affected both perceived internal and external employability, but the effect on the latter was stronger. These direct effects were in line with previous studies (Akkermans & Tims, 2017, Bargsted, 2017, Monteiro et al., 2018). These results suggest that young professionals’ reflection on motivation, work qualities, networking, self-profiling, work exploration and career control had a crucial role in improving employees’ perceived employability (Forrier et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2018, Blokker et al., 2019). Employees’ perception of their ability to maintain and develop jobs inside their organizations or to get desired ones outside has been considered an outcome of career competencies because mastering these competencies allows employees to have more positive perceptions of their ability to search, obtain and maintain employment (Akkermans et al., 2013). In addition, career competencies had stronger positive effects on perceived external employability than on perceived internal employability, which was also confirmed by Blokker et al., (2019). When employees could reflect on their competencies, communicate these competencies and have suitable plans as well as control in their jobs, they perceived themselves to be more employable outside their companies than inside their companies. In other words, higher career competencies led employees to find more work opportunities outside their organizations rather than inside their current organizations.

Career success (objective and subjective) partially mediated the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability, but career success (objective and subjective) was not related to perceived external employability.

The mediating role of subjective career success between career competencies and perceived internal employability coincided with the results of Blokker et al.(2019). This means that employees’ recognition, quality work, meaningful work, influence, authenticity, personal life, growth and development, and satisfaction had effects on their employability inside the current organization. In other words, better use of personal resources enabled young professionals to be more subjectively satisfied with their success (Kuijpers et al., 2006, Ahmad et al., 2019), leading to better maintenance and development of their careers inside the organization.

However, subjective career success was not related to perceived external employability, which was the opposite of the result found in the literature. According to Blokker et al. (2019), more subjective career success leads to a lower perception of external employability. The result of this study reveals that employees would stop finding job opportunities outside their organization if they had higher subjective career success. This result differentiates young professionals’ working behavior in Vietnam from others in developing countries such as those in research results of Blokker et al.(2019). It is obvious that, in the Vietnamese context, when young professionals gain more recognition, quality work, meaningful work, influence, authenticity, personal life, growth and development, and satisfaction, they tend to contribute more to their current organizations without thinking of quitting jobs and finding another one elsewhere. Besides, the Career Construction Theory of Savickas (2005) is proved insignificant in Vietnamese context when young professionals’ external employability is concerned. It’s because the assumption that career competency has a critical role in achieving career success and, subsequently, perceived employability among young professionals was only accepted with internal employability.

That objective career success partially mediates the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability is opposite to the result of Blokker et al. (2019), who concluded that objective career success did not have any mediating role between career competences and perceived internal employability. The results indicate that in the Vietnamese context, an increase in the salary rate, delegation rights, project responsibility and leadership position resulted in a higher perception of being employable internally. Consequently, employees could maintain and develop their careers better. Objective career success was not related to perceived external employability, which was also the conclusion of Blokker et al., (2019). Even when young professionals receive more salaries and responsibilities at work, their perceptions of being employable in the labor market will not change, and they will not seek outside opportunities.

Subjective career success (recognition, quality work, meaningful work, influence, authenticity, personal life, growth and development, and satisfaction) has a much stronger mediating role than objective career success (pay and hierarchical status) in the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability. That means that higher career competencies allow employees to have more subjective career success and be more internally employable. However, no mediating role of objective career success was found (Blokker et al., 2019).

Job crafting partially mediated the relationship between career competencies and perceived employability (both internally and externally). However, the mediating role of job crafting between career competencies and perceived external employability was stronger. These mediating roles were supported by Akkermans & Tims (2017) because career competencies were considered personal resources. Based on personal resources such as preferences, skills, and abilities, employees shape their employability (Berg & Dutton, 2008). Thanks to task variety and autonomy resulting in higher adaptability, young professionals’ perceptions of employability were boosted (Van Emmerik et al., 2012). Job crafting practices could lead to positive outcomes such as better person-job fit and job performance (Wang et al., 2016). When young professionals utilize their personal resources to make changes in their jobs, this leads to stimulation in personal growth and adaptability. Positive experiences such as achievement and resilience, such as the ability to cope with future adversity, makes them more employable inside their current organization (Berg et al., 2008). Moreover, these young professionals also are more attractive to the labor market, leading to their higher perception of external employability (Tims et al., 2012). Better career competencies enabled employees to make changes in their jobs, especially in cognitive and relational aspects, leading to being more employable both internally and externally. Different from career success, job crafting ability enables young professionals to succeed at the current jobs but also to get a job elsewhere. Though JD-R theory is proved to be true in Vietnamese context to conclude that job crafting has a mediating role in the relationship between job crafting and employability, social factors of leadership styles in job crafting permission which leads to more employability cannot be ignored (Wang et al., 2020).

Age and gender had effects on objective career success, while years of experience had impacts on job crafting. The age of young professionals in the survey ranged from 23 to 30 years old. The results showed that within that range, older professionals had higher objective career success. Additionally, male professionals had higher objective career success than female young professionals. The results coincided with the confirmation of Ng et al. (2005), who confirmed that “employees reported higher salary attainment if they were male… and older” (p. 21). In addition, the more experienced young professionals were, the less they did job crafting. Although both older and younger employees tended to take part in job crafting, younger employees engaged in all three types of task crafting, cognitive crafting and relation crafting, and there was a conjunction among the three (Baroudi & Khapova, 2017).

Conclusion

The main aim of the study was to investigate the role of career competencies in achieving career success and job crafting and, subsequently, perceived employability among a group of young professionals. The author used the combined model supported by Blokker et al. (2019) and Akkermans &Tims (2017) to examine whether career competencies would enable young professionals to construct their career success, job crafting and employability. The author found support for part of the hypothesized mediation model. As expected, young professionals with high levels of career competencies perceived themselves to be more employable both inside and outside their current organizations. While this relationship was partially mediated by job crafting, only the relationship between career competencies and perceived internal employability was mediated by career success (both objective and subjective). Career success has no effects on perceived external employability, leading to its no mediating role. The results also showed the effects of gender, age, and years of experience on objective career success and job crafting.

Theoretical implications

The results showed that the relationship between career competencies and employability via career success and job crafting is not straightforward.

Regarding career competencies and career success, young professionals who have developed high levels of career competencies became more satisfied with their career, leading to their perception of being more employable internally (Blokker et al., 2019) but not more employable externally. This suggests that career competencies and career success are not associated with higher perceptions of external employability. In contrast, subjective career success has been proven to have effects on perceived employability without the differentiation between perceived internal and external employability (Bargsted et al., 2021). This extends the literature to deny the mediating role of career success (both objective and subjective) in the relationship between career competencies and perceived external employability.

For career competencies and job crafting, when young professionals improved their career competencies, they could improve their job crafting, leading to their perception of being employable both internally and externally (Akkermans &Tims, 2017). Moreover, employees who can adapt to their tasks, cognition and relations, perceive themselves to be more employable both internally and externally, but they think of external opportunities more. This result might be highly applicable to the sample of young professionals in the study. An increase in crafting structure or challenges in job demands leads to increased responsibility, professional experience and networking, which are transferable to other jobs and organizations, meaning a higher feeling of external employment (Plomp et al., 2019). The confirmation of job crafting as a mediator between career competencies and employability among Vietnamese young professionals opens more space for research. Firstly, it’s because managerial support plays a very crucial role in boosting employees’ job crafting (Irfan et al., 2022). Secondly, HR flexibility which can be decided by social and cultural characteristics is the thing that equip young professionals with knowledge, skills, and autonomy to craft their jobs both individually and collaboratively (Tuan, 2019). These make job crafting worth a closer and more contextual look in terms of leadership styles in different organizations in Vietnamese context.

Moreover, the author expected there to be a mediating role of career success and job crafting in the relationship between career competencies and perceived employability (both internal and external), but the results showed that only job crafting was the mediator of both career competencies and perceived internal and external employability. Meanwhile, career success (both objective and subjective) does not affect perceived external employability. These findings imply that differentiating between perceived internal employability and external employability is important for examining their interrelations. This distinction will contribute to the understanding of internal and external opportunities within and outside organizations (Van Emmerik et al., 2012). Besides, the absence of the mediating role of career success in the relationship between career competencies and internal perceived employability suggests that Career Construction Theory (Savickas, 2005) and other considerations of this mediating role should be regarded under the distinctions of cultural and contextual issues.

Practical implications

Our results have practical implications for young professionals, HR managers and career advisors.

First, the study shows that career competencies are a career source that is positively associated with achieving career success and necessary changes in jobs (in terms of tasks, relation and cognition) and subsequently employability (Akkermans & Tims, 2017, Blokker et al., 2019).

This means that young professionals with good career competency development are likely to have better chances for long-term success and career adaptation (Kuijpers et al., 2006, Dumulescu et al., 2015). At the same time, employees who are aware of their changes and make changes in their tasks, relations and recognition in the workplace perceive themselves to be more employable not only inside their current organizations but also on the market (Berg et al., 2008, Vogt et al., 2016).

Therefore, young professionals should invest their time and effort into developing their career sources and have a flexible attitudes when adapting to the workplace (by changing their tasks, updating their networks and improving their cognition) to avoid just following their daily routine tasks monotonously to improve their work performance (Singh & Singh, 2018) and thus their employability.

HR managers could use the findings of the study to help young professionals build their employability. In particular, HR managers could propose training programs to enable young professionals to take the initiative to apply new ways or techniques at work and engage more in networking activities. Companies can implement opportunity-enhancing high-performance work practices to enable employees to express their adaptability through job crafting, leading to higher work engagement (Federici et al., 2021). Regarding turnover rate, HR managers can increase young professionals’ subjective career success by proposing policies aimed at enhancing young professionals’ satisfaction, recognition, meaningful work or creating more chances for young professionals’ growth and development, thus making young professionals’ focus on internal employability. This can result in reducing the current turnover rate (Nguyen &Tran, 2021, Talluri &Uppal, 2022).

Moreover, HR managers could also apply policies to boost young professionals’ job crafting with more flexibility in HR practices (Tuan, 2019) such as letting them mentor new employees or take new networking responsibilities, such as holding a birthday party for a coworker.

Limitations and suggestions for further studies

The study employs a quantitative method in the form of a survey. Although the quantitative method enables researchers to obtain accurate and reliable measurements that allow statistical analysis, the survey method bears the nature of rigidity in terms of structure, leading to the failure to capture emotions, behavior and changes in emotions of respondents (Queirós et al., 2017). Therefore, the limitation of the study is also this, especially with the mediating role of job crafting between career competencies and perceived employability. A qualitative method might be used to explore the role of career competencies in job crafting initiatives and the extent to which job crafting is allowed in companies from HR managers’ perspectives, leading to improving young professionals’ employability. The qualitative methodology enables researchers to understand a complicated reality as well as the meaning of actions in a given context (Queirós et al., 2017). At the same time, job crafting is a complex phenomenon, and understanding it is a large and lasting challenge for managers (Berg et al., 2008). In addition, context is also a very important factor in the job crafting process (Lazazzara et al., 2020). This research direction may bring about a more comprehensive understanding of new antecedents and outcomes of job crafting using job demands and resources (JD-R) theory as not much research has been done in Vietnamese context with focus on HRM practices.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratitudes to Professor Géraldine Schmidt at IAE Paris—Université Paris 1, Sorbonne Business School, France and Professor Clotilde Coron at Universite-paris-saclay, France for their support and guidance.

Biographical note

Dinh Thi Ngoan is currently working as a lecturer of Foreign Trade University, 91 Chua Lang Street, Dong Da District, Hanoi Capital, Vietnam. She did a master’s degree in Teaching Methodology and completed a master’s degree 2 in Research in Management, Lille 2 University, France. Currently, she is a Phd Candidate of HRM at IAE Paris – Université Paris 1, Sorbonne Business School, France. Her ORCID is https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0507-9961.

Bibliography

- Abbasi, F. K., Ali, A., & Bibi, N. (2018). Analysis of skill gap for business graduates: managerial perspective from banking industry. Education+ Training. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-08-2017-0120

- ADECCO (2020) ‘Adecco Vietnam Salary Guide 2020’, pp. 1–24. Available at: https://adecco.com.vn//uploads/Adecco-Vietnam-Salary-Guide-2020.pdf.

- Ahmad, B., Latif, S., Bilal, A. R., & Hai, M. (2019). The mediating role of career resilience on the relationship between career competency and career success: an empirical investigation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-04-2019-0079

- Akkermans, J., & Tims, M. (2017). Crafting your career: How career competencies relate to career success via job crafting. Applied Psychology, 66(1), 168–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12082

- Akkermans, J., Brenninkmeijer, V., Huibers, M., & Blonk, R. W. (2013). Competencies for the contemporary career: Development and preliminary validation of the career competencies questionnaire. Journal of Career Development, 40(3), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845312467501

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of managerial psychology. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands—resources theory. Wellbeing: A complete reference guide, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell019

- Bargsted, M. (2017). Impact of personal competencies and market value of type of occupation over objective employability and perceived career opportunities of young professionals. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 33(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2017.02.003

- Bargsted, M., Yeves, J., Merino, C., & Venegas-Muggli, J. I. (2021). Career success is not always an outcome: Its mediating role between competence employability model and perceived employability. Career Development International. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-06-2020-0141

- Baroudi, S. E., & Khapova, S. N. (2017). The effects of age on job crafting: Exploring the motivations and behavior of younger and older employees in job crafting. In Leadership, innovation and entrepreneurship as driving forces of the global economy (pp. 485–505). Springer, Cham.

- Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2008). Crafting a fulfilling job: Bringing passion into work. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Ross School of Business, 1–8.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2008). What is job crafting and why does it matter? Retrieved from the website of Positive Organizational Scholarship on April, 15, 2011.

- Blokker, R., Akkermans, J., Tims, M., Jansen, P., & Khapova, S. (2019). Building a sustainable start: The role of career competencies, career success, and career shocks in young professionals’ employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.02.013

- Cameron, R., Dhakal, S., & Burgess, J. (2017). Transitions from education to work. Workforce Ready Challenges in the Asia Pacific, London: Routledge.

- Chen, T. L., Shen, C. C., & Gosling, M. (2018). Does employability increase with internship satisfaction? Enhanced employability and internship satisfaction in a hospitality program. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 22, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2018.04.001

- Chhinzer, N., & Russo, A. M. (2017). An exploration of employer perceptions of graduate student employability. Education+ Training. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2016-0111

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demandsresources model of burnout. Journal of Applied psychology, 86(3), 499. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Dinh, N. T., Dinh Hai, L., & Pham, H. H. (2022). A bibliometric review of research on employability: dataset from Scopus between 1972 and 2019. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-02-2022-0031

- Dumulescu, D., Balazsi, R., & Opre, A. (2015). Calling and career competencies among Romanian students: the mediating role of career adaptability. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.223

- Federici, E., Boon, C., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2021). The moderating role of HR practices on the career adaptability—job crafting relationship: a study among employee—manager dyads. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(6), 1339–1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1522656

- Figueiredo, H., Biscaia, R., Rocha, V., & Teixeira, P. (2017). Should we start worrying? Mass higher education, skill demand and the increasingly complex landscape of young graduates’ employment. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1401–1420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1101754

- Forrier, A., De Cuyper, N., & Akkermans, J. (2018). The winner takes it all, the loser has to fall: Provoking the agency perspective in employability research. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12206

- Forrier, A., Verbruggen, M., & De Cuyper, N. (2015). Integrating different notions of employability in a dynamic chain: The relationship between job transitions, movement capital and perceived employability. Journal of Vocational behavior, 89, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.04.007

- Guilbert, L., Bernaud, J. L., Gouvernet, B., & Rossier, J. (2016). Employability: review and research prospects. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 16(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9288-4

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage publications.

- Hair, J. F., Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about partial least squares: comments on Rönkkö and Evermann. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114526928

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM : Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Haymora (2019). Bao Cao Khao Sat Nam 2019: Ty le nghi viec co the len 24%, co toi 50% nhan su khong trung thanh va kem no luc. https://haymora.com/blog/bao-cao-khao-sat-2019-ty-le-nghi-viec-co-the-len-24-co-toi-50-nhan-su-khong-trung-thanh-va-kem-no-luc/

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hill, M. A., Overton, T. L., Thompson, C. D., Kitson, R. R., & Coppo, P. (2019). Undergraduate recognition of curriculum-related skill development and the skills employers are seeking. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 20(1), 68–84. DOI: 10.1039/C8RP00105G

- Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: developing a framework for policy analysis.

- Hogan, R., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Kaiser, R. B. (2013). Employability and career success: Bridging the gap between theory and reality. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12001

- Irfan, S. M., Qadeer, F., Abdullah, M. I., & Sarfraz, M. (2022). Employer’s investments in job crafting to promote knowledge worker’s sustainable employability: a moderated mediation model. Personnel Review, (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2021-0704

- Irfan, S., & Qadeer, F. (2020). Employers’ investments in job crafting for sustainable employability in pandemic situation due to COVID-19: A lens of job demands-resources theory. Journal of Business & Economics, 12(2). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3770645

- Jackson, L. A., Ervin, K. S., Gardner, P. D., & Schmitt, N. (2001). Gender and the Internet: Women communicating and men searching. Sex roles, 44(5), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010937901821

- Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz Jr, R. D. (1995). An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel psychology, 48(3), 485–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01767.x

- Juhdi, N., Pa’wan, F., Othman, N. A., & Moksin, H. (2010). Factors influencing internal and external employability of employees. Business and Economics Journal, 11(1–10).

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (ijec), 11(4), 1–10.

- Kong, H., Cheung, C., & Song, H. (2012). Determinants and outcome of career competencies: Perspectives of hotel managers in China. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.007

- Kuijpers, M. A., Schyns, B., & Scheerens, J. (2006). Career competencies for career success. The Career Development Quarterly, 55(2), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00011.x

- Lazazzara, A., Tims, M., & De Gennaro, D. (2020). The process of reinventing a job: A meta–synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.01.001

- London, M., & Stumpf, S. A. (1982). Managing careers (Vol. 4559). Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

- Masduki, N. A., Mahfar, M., & Senin, A. A. (2022). A bibliometric analysis of the graduate employability research trends. In International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 11(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v11i1.22145

- Matsouka, K., & Mihail, D. M. (2016). Graduates’ employability: What do graduates and employers think?. Industry and Higher Education, 30(5), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222166637

- Monteiro, S., Ferreira, J. A., & Almeida, L. S. (2020). Self-perceived competency and self-perceived employability in higher education: the mediating role of career adaptability. Journal of further and Higher Education, 44(3), 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1542669

- Ng, T. W., Eby, L. T., Sorensen, K. L., & Feldman, D. C. (2005). Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta-analysis. Personnel psychology, 58(2), 367–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00515.x

- Nghia, T. L. H., Giang, H. T., & Quyen, V. P. (2019). At-home international education in Vietnamese universities: Impact on graduates’ employability and career prospects. Higher Education, 78(5), 817–834. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00372-w

- Nguyen, D. T. N., Teo, S. T., & Ho, M. (2018). Development of human resource management in Vietnam: A semantic analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(1), 241–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9522-3

- Nguyen, Q. A., & Tran, A. D. (2021). Job satisfaction and turnover intention of preventive medicine workers in northern Vietnam: Is there any relationship?. Health Services Insights, 14, 1178632921995172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632921995172

- Niu, Y., Hunter-Johnson, Y., Xu, X., & Liu, T. (2019). Self-perceived employability and subjective career success: Graduates of a workforce education and development program. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 67(2–3), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2019.1660843

- Noori, M. I., & Azmi, F. T. (2021). Students Perceived Employability: A Systematic Literature Search and Bibliometric Analysis. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 14(28), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.17015/ejbe.2021.028.03

- Plomp, J., Tims, M., Khapova, S. N., Jansen, P. G., & Bakker, A. B. (2019). Psychological safety, job crafting, and employability: A comparison between permanent and temporary workers. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 974. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00974

- Presti, A. L., Capone, V., Aversano, A., & Akkermans, J. (2022). Career competencies and career success: On the roles of employability activities and academic satisfaction during the school-to-work transition. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/08948453219925

- Prikshat, V., Nankervis, A., Brown, K., Cameron, R., Burgess, J., Connell, J., Dhakal, S., & Mumme, B. (2016). Graduate work-readiness challenges in the Asia Pacific: The role of HRM in a multiple-stakeholder strategy. International Conference on Human Resource Management (IHRM), Victoria, 21–23.

- Queirós, A., Faria, D., & Almeida, F. (2017). Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. European journal of education studies, 369–387. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.887089

- Ressia, S., & Shaw, A. (2022). Employability outcomes of human resource management and employment relations graduates. Labour and Industry, 32(2), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2022.2093736

- Römgens, I., Scoupe, R., & Beausaert, S. (2020). Unraveling the concept of employability, bringing together research on employability in higher education and the workplace. Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2588–2603. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1623770

- Rothwell, A., & Rothwell, F. (2017). Graduate employability: A critical oversight. In Graduate employability in context (pp. 41–63). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Rothwell, A., Jewell, S., & Hardie, M. (2009). Self-perceived employability: Investigating the responses of post-graduate students. Journal of vocational behavior, 75(2), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.05.002

- Sanders, J., & De Grip, A. (2004). Training, task flexibility and the employability of low-skilled workers. International Journal of Manpower, 25(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720410525009

- Sartori, R., Tommasi, F., Ceschi, A., Giusto, G., Morandini, S., Caputo, B., & Gostimir, M. (2022). Fostering employability at work through job crafting. Psychological Applications and Trends, 376. https://hdl.handle.net/11562/1062365

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, 1, 42–70.

- Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of vocational behavior, 80(3), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

- Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. Journal of applied psychology, 84(3), 416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416

- Singh, S., & Ehlers, S. (2020). Employability as a Global Norm : Comparing Transnational Employability Policies of OECD, ILO, World Bank Group, and UNESCO. International and Comparative Studies in Adult and Continuing Education, 12, 131. https://doi.org/10.36253/978-88-5518-155-6

- Singh, V., & Singh, M. (2018). A burnout model of job crafting: Multiple mediator effects on job performance. IIMB management review, 30(4), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2018.05.001

- Smith, W. G. (2008). Does gender influence online survey participation? A record-linkage analysis of university faculty online survey response behavior. Eric Ed501717, 501717, 1–21. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED501717.pdf

- Succi, C., & Canovi, M. (2020). Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Studies in higher education, 45(9), 1834–1847. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420

- Sumanasiri, E. G. T., Yajid, M. S. A., & Khatibi, A. (2015). Review of literature on graduate employability. Journal of Studies in Education, 5(3), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v5i3.7983

- Talluri, S. B., & Uppal, N. (2022). Subjective Career Success, Career Competencies, and Perceived Employability: Three-way Interaction Effects on Organizational and Occupational Turnover Intentions. Journal of Career Assessment, 10690727221119452. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727221119452

- Thang, P. V. M., & Wongsurawat, W. (2016). Enhancing the employability of IT graduates in Vietnam. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 6(2), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-07-2015-0043

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC89228

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of vocational behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Tong, L. (2019). Graduate employment in Vietnam. International Higher Education, (97), 22–23. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2019.97.10948

- Tran, T. T. (2015). Is graduate employability the ‘whole-of-higher-education-issue’?. Journal of Education and Work, 28(3), 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2014.900167

- Tseng, M. S. (1972). Need for achievement as a determinant of job proficiency, employability, and training satisfaction of vocational rehabilitation clients. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 2(3), 301– 307. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(72)90037-1

- Tuan, L. T. (2019). HR flexibility and job crafting in public organizations: The roles of knowledge sharing and public service motivation. Group & Organization Management, 44(3), 549–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601117741818

- Urbach, N., & Ahlemann, F. (2010). Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application (JITTA), 11(2), 2. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/jitta/vol11/iss2/2

- Van Der Heijde, C. M. (2014). Employability and self-regulation in contemporary careers. In Psychosocial career meta-capacities (pp. 7–17). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00645-1_1

- Van Emmerik, I. H., Schreurs, B., De Cuyper, N., Jawahar, I. M., & Peeters, M. C. (2012). The route to employability: Examining resources and the mediating role of motivation. Career Development International. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431211225304

- Vargas, R., Sánchez-Queija, M. I., Rothwell, A., & Parra, Á. (2018). Self-perceived employability in Spain. Education and Training, 60(3), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-03-2017-0037

- Vietnamnews.net (2019) ‘Employee turnover rate reached alarming high’. Available at: https://vietnamnews.vn/society/536372/employee-turnover-rate-reached-alarming-high-report.html on 23rd May 2020.

- VIETNAMPLUS.VN (2020) Q1 unemployment rate highest in five year due to Vietnam bolsters ASEAN cooperation in. Available at: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/q1-unemployment-rate-highest-in-five-yeardue-to-covid19/172481.vnp.

- Vogt, K., Hakanen, J. J., Brauchli, R., Jenny, G. J., & Bauer, G. F. (2016). The consequences of job crafting: A three-wave study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 353– 362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1072170

- Wang, H., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). A review of job-crafting research: The role of leader behaviors in cultivating successful job crafters. Proactivity at work, 95–122.

- Wang, H., Li, P., & Chen, S. (2020). The impact of social factors on job crafting: a meta-analysis and review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218016

- Williams, S., Dodd, L. J., Steele, C., & Randall, R. (2016). A systematic review of current understandings of employability. Journal of education and work, 29(8), 877–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1102210

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job : Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of management review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378011

- Yao, C. W., & Tuliao, M. D. (2019). Soft skill development for employability: A case study of stem graduate students at a Vietnamese transnational university. Higher Education, Skills and WorkBased Learning. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-03-2018-0027

- Yorke, M. (2006). Employability in higher education: what it is-what it is not (Vol. 1). York: Higher Education Academy.

Appendices

Note biographique

Dinh Thi Ngoan travaille actuellement comme enseignante à l’Ecole supérieure de commerce extérieur, 91 rue Chua Lang, arrondissement de Dong Da, capitale de Hanoï, Vietnam. Elle a fait une maîtrise en méthodologie d’enseignement et a complété un master de recherche en gestion, Université Lille 2, France. Actuellement, elle est doctorante en GRH à l’IAE Paris - Université Paris 1, Sorbonne Business School, France. Son ORCID est https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0507-9961.

Appendices

Nota biográfica

Dinh Thi Ngoan trabaja actualmente como profesora de la Universidad de Comercio Exterior, 91 Chua Lang Street, distrito de Dong Da, capital de Hanoi, Vietnam. Realizó una maestría en Metodología de la Enseñanza y completó una maestría 2 en Investigación en Gestión, Universidad de Lille 2, Francia. Actualmente, es candidata al doctorado de Gestión de Recursos Humanos en la universidad IAE París - Universidad París 1, Sorbonne Business School, Francia. Su ORCID es https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0507-9961.

List of figures

Figure 1

An illustration of the hypothesized relationship (H. hyphothesis)

List of tables

Table I

Three Perspectives in Employability Research

Table II

Constructs and Measurement Scale

Table III

Means, Standard deviations, and Correlations Among Study Variables (N=957)

Table IV

Measurement Model Evaluation (higher-order construct)

Table V

Measuremet Model Evaluation (lower-order construct)

Table VI

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

Table VII

VIF Values - Common Method Bias (CMB)

Table VIII

Hypothesis Testing