Abstracts

Abstract

Although scholars recognize the need to integrate stakeholders into business model innovation (BMI), little research has been done on the link between stakeholders’ roles and young ventures’ BMI, particularly in the accelerator context. We addressed this research gap by conducting a longitudinal multi-case study in two corporate accelerators using semi-structured interviews, observations and documentation from young ventures’ perspective. Our results offer a more granular understanding of how different stakeholders enable the configuration of young ventures’ initial BM and spur BMI. Specifically, the study provides some original insights into accelerator ecosystems, networking activities and the contributions of both to young ventures’ BMI.

Keywords:

- Business model innovation,

- stakeholder roles,

- corporate accelerator,

- young ventures

Résumé

Les chercheurs reconnaissent la nécessité d’intégrer les parties prenantes dans l’innovation des business model (IBM), cependant le lien entre les rôles des parties prenantes et l’IBM des jeunes entreprises reste peu étudié, en particulier dans le contexte des accélérateurs. Nous avons mené une étude longitudinale multi-cas dans deux accélérateurs en utilisant des entretiens semi-directifs, des observations et des données secondaires. Nos résultats offrent une compréhension plus granulaire de la façon dont les différentes parties prenantes permettent la reconfiguration du BM initial des jeunes entreprises et gênèrent l’IBM. Plus précisément, l’étude fournit des apports originaux sur les écosystèmes des accélérateurs, les activités de mise en réseau et leur contribution à l’IBM des jeunes entreprises.

Mots-clés :

- Business model innovation,

- rôles des parties prenantes,

- accélérateur d’entreprise,

- jeunes entreprises

Resumen

Aunque los investigadores reconocen la necesidad de integrar a las partes interesadas en la innovación del modelo de negocio (IMN), la relación entre el papel de las partes interesadas y la IMN de las empresas de reciente creación sigue sin estar suficientemente estudiada, sobre todo en el contexto de las aceleradoras. Realizamos un estudio longitudinal de casos múltiples en dos aceleradores utilizando entrevistas semiestructuradas, observaciones y bibliografía. Nuestros resultados proporcionan una comprensión más detallada de cómo las diferentes partes interesadas contribuyen a dar forma al modelo de negocio de las start-ups y a estimular los INM. En particular, el estudio ofrece una visión original de los ecosistemas de aceleración, las actividades de creación de redes y la contribución de ambos a los INM de nueva creación.

Palabras clave:

- IInnovación del modelo de negocio,

- roles de las partes interesadas,

- acelerador corporativo,

- jóvenes empresas

Article body

Corporate accelerators aim to develop an ecosystem of young ventures and selected partners and create interactions among them (Kohler, 2016; Richter et al., 2018). Indeed, those accelerators facilitate collaborations between young ventures that are developing promising technologies and products and corporate accelerator’s founders, partners and clients. Young ventures may then deliver value to those internal and external stakeholders by developing new solutions for them. Many types of corporate accelerators coexist and manifest different forms of support and levels of involvement in young ventures’ operations (Hochberg, 2016).

A new type of entrepreneurship support programme based on network acceleration has emerged. These network accelerators emphasize the role of social relationships among organizations to obtain access to external resources and opportunities (Cohen et al., 2019). These relationships allow young ventures to refine their business model (BM) insofar as these BMs are not defined in isolation (Lubik and Garnsey, 2016; Marion et al., 2015).

BM refers to the way young ventures create and capture value. They can be considered an activity system of interdependent activities (Zott and Amit, 2010), performed by the company itself and externally by its partners, subcontractors, suppliers, customers, etc. This definition emphasizes the interrelationships among companies that occur at the BM level. The relationships that young ventures maintain within the corporate accelerator can also trigger BMI, which manifests through new logics to create and capture value.

Relying on Snihur and Zott’s (2020) work, we consider BMI to emerge by adding new activities (novel content), bringing in new partners to perform specific activities (novel governance), or linking activities in novel ways (novel structure).

Accordingly, information and discussions with mentors of the accelerator lead to new strategic orientation and the conception of new BM alternatives (Cohen et al., 2019). In addition, corporate accelerators can also rely on a broader network of partners, which may become involved in young ventures’ BMI by bringing additional resources such as founding or new opportunities. However, we lack an understanding of the role of the different stakeholders of corporate accelerators on young venture BMI (Usman and Vanhaverbeke, 2017) and, more particularly, why some ventures manifest BMI and others maintain their initial BM in corporate accelerators.

Our limited understanding of young venture BMI in relation to corporate accelerator ecosystems is problematic because changes in the BM are particularly significant in a venture’s first years of existence and show its capacity to apprehend the ecosystem that surrounds it (Miller et al., 2014; Snihur and Zott, 2020).

In that respect, scholars argue that a firm’s BMI manifests through exploitation and exploration activities and that those activities may be influenced, for example, by institutional investors’ choice of exploration versus exploitation for their joint ventures (Connelly et al., 2019). However, those activities involve different types of learning and configurations of resources. Exploration refers to the search for new resources and knowledge to innovate beyond the boundaries of the existing BMs, which involves learning based on risk-taking and experimentation (Mehrizi and Lashkarbolouki, 2016). In contrast, exploitation refers to the refinement of existing resources and competences to innovate with existing BMs (Sinha, 2015; Wilden et al., 2018). Few studies have demonstrated that the influence of stakeholders shapes young ventures’ BMI, particularly in accelerators (Rydehell, 2020). However, those works have not described how interactions with accelerator stakeholders orient BMI towards either exploitation or a simultaneous conduit of exploration and exploitation.

This paper reports on the findings from an empirical study of 10 young ventures located in two accelerators from the French accelerator network “Village by CA”, which was established by one of the major banks in France, “Crédit Agricole”, in 2014. These accelerators mostly aim to connect young ventures from various territories with regional and national business networks.

The study provides some interesting results. We find that interactions with corporate stakeholders influence young ventures’ explorative or explorative intention. Next, the relationship between corporate accelerator stakeholders and young venture BMs is dynamic, as corporate accelerator stakeholders’ roles differ and change over time according to young ventures’ needs and interest in their exploration and exploitation activities. Furthermore, our research shows that young ventures reconfigure their initial BM mainly through explorative activities that involve stakeholders of different corporate accelerators. Finally, we find that young ventures’ BM evolves though a cocreation of value and/or a series of transitions, while various corporate accelerator stakeholders continually shape young ventures’ initial BM.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we discuss the concept of BMI, its articulation in young ventures and the role of corporate accelerators’ stakeholders. Then, we empirically analyse the influence of corporate accelerator stakeholders on young ventures’ BMI through our exploratory multiple case study. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of our findings.

Literature review

Young ventures’ BMI and the search for exploration and exploitation

Young ventures are increasingly relying on BMI to ensure their development, as the content and novelty aspect of a BM are defined and shaped in the first years of a venture (Foss and Saebi, 2017; Snihur and Zott, 2020). Recent studies have focused particularly on the pivot process through which young ventures change their initial BM to face a potential failure or after a failure of their initial BM (Hampel et al., 2020). However, despite its economic importance, little is known about the mechanisms through which BMI emerges in young ventures, which manifests when the company improves at least one of the dimensions of value (value creation and value capture) (Abdelkafi et al., 2013). Indeed, several scholars point out that the reconfiguration of BM goes through different degrees of novelty starting from minors’ changes in initial firm BM to radical changes leading to a completely new BM either for the company or for the industry where it operates (Foss and Saebi, 2017; Snihur and Zott, 2020; Warnier et al., 2018). Existing scholars have identified different typologies of BMI according to their degree of novelty and changes in BM components and have demonstrated how to implement them (Garreau et al., 2015; Moyon and Lecocq, 2014). However, the intention of managerial team to conduct these changes have not been explored.

In that respect, Osiyevskyy and Dewald (2015) compare exploitative BM change, which involves minor adjustments to the existing BM of the company along its established trajectory, and exploratory BM change, which aims at offering new products and services and involves transforming the value creation process and its distribution among the value chain. That perspective is grounded in an activity-system perspective of the BM (Zott and Amit, 2010). This perspective sheds particular light on the impact of the transformation of the BM, as exploitation does not change the existing logic of complementary activities, whereas exploration supposes a redesign of the activity system and rethinks complementarity between activities (Osiyevskyy and Dewald, 2018).

Existing studies have already established that companies should carry out both exploratory and exploitative BMI either by conducting the two activities simultaneously (Smith et al., 2010) or by going through cycles of exploitation and exploration sequentially (Sosna et al., 2010). Those works either have particularly emphasized internal tensions related to regular shifts between exploratory and exploitative BM or to the development of complex BM, which combine the two approaches. In particular, the exploration of new BM involves the integration of new components into existing BMs and the absorption of external knowledge, which is recombined with internal resources, whereas the exploitation of BM is based on the reinforcement of routines and knowledge transfer within the value chain (Osiyevskyy and Dewald, 2018; Simon and Tellier, 2011) as a consequence, it has been demonstrated that firms should separate their value chain to various degrees to combine BMI exploration and exploitation (Winterhalter et al., 2015). However, those studies have been carried out in established companies, which are characterized by inertia and possibly strong lock-in effects, as changes in the external environment make the existing BM of the company inefficient (Sosna et al., 2010). In contrast, young ventures would be more permeable to the influence of external stakeholders to adapt their BM, as those stakeholders palliate their lack of resources and competences (Rydehell, 2020). Thus, instead of reconfiguring their internal activities, which characterize the value chain, we propose that young ventures rely on their value network, which is associated with the relationships that a company has with different external partners to deliver value, to achieve both BMI exploration and exploitation. Thus, external interorganizational relationships could solve the tension between exploitation and exploration in BMI (Kringelum and Gjerding, 2018). In that respect, the general model of our research is synthetized in Figure 1.

Table 1

Definition of initial BM and BMI

Figure 1

General model of young ventures’ BMI process in an accelerator context

The accelerator stakeholders’ influence in BMI

As described in figure 1, managers of young ventures have an intention to change their BM; however, they do not completely control the outcome. Thus, similar to the conclusions of the article by Simon and Tellier (2011) on innovation projects, managers experiment to reconfigure their initial BM, and even though they may want to explore or exploit, the final result in terms of the scope of change impacting the BM elements and its system of activities may vary from their initial intention. BMI is then a trial-and-error process that allows collective learning about exploration and exploitation (Osiyevskyy and Dewald, 2015; Sosna et al., 2010). More particularly, BMI emerges through a series of transitions due to the influence of multiple stakeholders (Miller et al., 2014; Rydehell, 2020). According to Garreau et al. (2015), the connextion with stakeholders can lead to a more or less significant changes in BM. Existing works highlight different areas of BMI, which are triggered by stakeholders’ influence. First, interactions with stakeholders impact mental schemas and thus change the perception that the new ventures’ founders have on their BMs and how to do business (Rydehell, 2020). Then, they also shape the young venture’s learning about customers’ preferences and its technological know-how (Usman and Vanhaverbeke, 2017). Thus, they impact the generation of value creation and the set of competences available to deploy BMI (Scillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). In this sense, stakeholders provide a new resources and competences enabling them to redefine the scope of its BM by internalizing or outsourcing their activities (Garreau et al., 2015).

Then, stakeholders can also recommend young ventures to new partners, which could then collaborate to propose new activities or participate to rethink the way activities are produced. Furthermore, some scholars reveal that relationships developed with stakeholders stimulate the dynamic capabilities of young ventures to identify and seize different opportunities (Ruiz-Ortega et al., 2017, Snihur and Zott, 2020). However, ecosystems or stakeholders in young ventures’ BMI are conceived with a broad perspective, and we lack a more precise understanding of the specific role of different corporate accelerators’ stakeholders on young ventures’ BMI and more particularly on exploratory or exploitative innovation in BM (Cohen et al., 2019). Indeed, BMI emerge differently from one context to another and depend on their process of implementation (Alkhanbouli et al., 2020). Thus, in the next section, we describe the specific role of accelerator stakeholders and demonstrate their interplay in shaping BMI.

The role of corporate accelerator stakeholders

The influence of stakeholders is even more substantial in corporate accelerator programs and needs to be explored. Indeed, many corporations are initiating acceleration programs that support young ventures through their ecosystem of a multitude of actors, which is considered a microecosystem of the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Banc and Messeghem, 2020). Although corporations are adopting different forms and approaches to design their acceleration program (Hochberg, 2016), they aim to support young ventures by providing their resources and the competences of their employees through mentoring, as well as with those of established companies, which are often their partners or clients. In that respect, Vandeweghe and Fu (2018) differentiate between internal stakeholders of corporate accelerators such as sponsors, directors and staff and external stakeholders such as partners, investors and portfolio companies. For example, instead of offering investment to ventures, they connect them with potential investors and financial structures, such as bank or business angels. Those investors are then external stakeholders.

Extant scholars consider corporate accelerators as ecosystem builders (Kohler, 2016; Pauwels et al., 2016; Richter et al., 2018) that seek to develop an ecosystem of ventures and established companies around their companies and create interactions among them to enrich each other. Cohen et al. (2019) show that corporate coaches such as sponsors or staff can spur young ventures’ BMI through discussions that often lead to new BM orientations, the development of new products or the creation of BM alternatives. These corporate coaches are considered advisers and providers of know-how in different areas, such as business planning and marketing. They are also connectors that help ventures create their own ecosystem that is unique from that of the accelerator.

Moreover, as far as external stakeholders are concerned, Kohler (2016) suggests that established companies may codevelop new products with young ventures, acting as evaluators that enable young ventures to test and validate their value propositions and as investors that provide capital. Those different stakeholders maintain a complex set of relationships with the young ventures’ management team as the flow of resources, which circulate in bilateral relationships and provide insights to other actors to determine whether they should invest (or not) in the young ventures. Furthermore, corporate accelerator stakeholders may have different objectives than young ventures about their collaboration. This situation may lead to conflicts of interest between corporate accelerator stakeholders and young ventures, which hinder their collaboration and eventuality value creation (Vandeweghe and Fu, 2018). However, we still know little about the networking activities of corporate accelerators and, more particularly, about the different roles played by internal and external stakeholders of the accelerators on young ventures’ BMI.

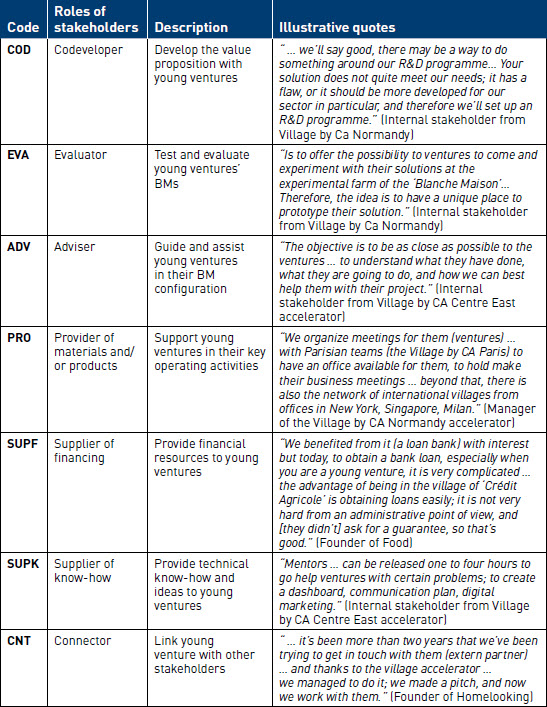

Accordingly, we choose to transpose the work of Rydehell (2020) in the context of accelerators to investigate the interrelated influence of their stakeholders on BMI. That work contributes to defining the roles played by stakeholders in young ventures’ BM reconfiguration, as actors are defined not only according to the resources that they provide to young ventures but also according to other effects that occur due to changes in BM. Indeed, young ventures’ desire to reconfigure that BM may change according to interactions with stakeholders (Reymen et al., 2017). Then, this perspective allows us to analyse the link between the intentions of young ventures in terms of exploration activities and exploitation and the roles of their interorganizational relationship in those activities, which propel BMI. We define stakeholders’ role as “a function that someone performs in certain circumstances or an explanation of what someone does when undertaking certain activities.” Rydehell (2020, p 7). Thus, Rydehell (2020) identifies six different roles assumed by stakeholders in a young venture BM: codevelopers work “in close collaboration” with young ventures and help them develop their offerings, especially their value propositions. Evaluators enable young ventures to test and evaluate their offerings. Advisers guide and assist young ventures in their BM configuration. Providers may supply materials and/or products that are necessary for young ventures’ operating activities, financial resources, or technical know-how/ideas to young ventures. Finally, connectors link young ventures with other stakeholders. The role of stakeholders may change over time according to the stage of the young ventures.

To study the role of corporate accelerator stakeholders in BMI, we undertook comparative case studies of 10 young ventures hosted in two accelerator programmes. The next section describes the data collection and analysis processes.

Method

We conducted multiple case studies to evaluate emerging and complex phenomena (Yin, 2014). Our research was conducted in real time between 2017 and 2019. This approach is completed by retrospective research to examine previous BMI situations that we had not observed as they unfolded. This approach allowed us to keep track of young ventures’ BMI and the involvement of stakeholders over time. A cross-sectional study was used to consider BM dynamics and eventually BMI (Sosna et al., 2010). In addition, as far as the BM is represented through different perspectives, involving different levels and units of analysis (Massa et al., 2017), we follow the perspective of real elements of the BM identified by Massa et al. (2017). This perspective allows understanding the company and its value network as they are. Then, our unit of analysis is young ventures’ BM and their network value, and we consider BMI from the point of view of young ventures, as the BM includes the value network through which ventures maintain their relations with their different stakeholders (Zott and Amit, 2010).

Case selection

We selected 10 young ventures from two accelerators to achieve relevant observations, as recommended in multiple case studies (Eisenhardt, 1989). Using a sample size of 10 young ventures increases richness and variation. The selection of these cases was carried out according to theoretical patterns (Miles and Huberman, 2003) that rely on Rispal’s (2002) criteria: young ventures selected for this study come from different sectors and regions of France. Most of the young ventures were hosted in the accelerator (residents), but others had their office either in the same region as the accelerator or in another region (non-residents).

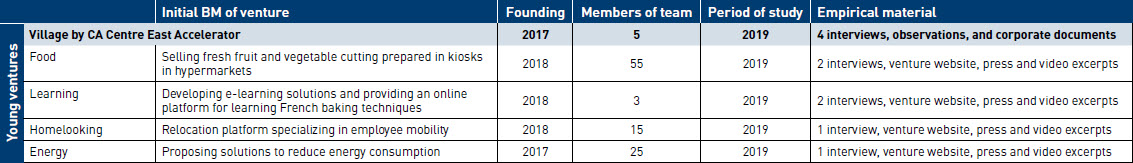

First, we track seven young ventures in the village by CA Normandy that represent our exploratory sampling. Then, we confirm our primary results by comparing them with the cases of four young ventures in Village by the CA Centre East. This research design allowed us to conduct a comparative and in-depth analysis of stakeholders’ roles and influences on different dimensions of young ventures’ BMI.

The two accelerators belong to the network of Village by CA to control factors relative to the particular context of the accelerator. First, the Village by CA Normandy was launched in June 2016 in Caen in Normandy. It is considered unique in Europe as it was founded and has been supported by four public and private companies from different sectors, which wanted to foster innovation in the agriculture field thanks to their program Agri’up. The second accelerator, “Village by Ca Centre Est”, was founded in September 2017 and has been supported by the Lyon regional bank of “Crédit Agricole”. Accordingly, we identify both internal and external stakeholders in both villages by the Ca Normandy accelerator village by the Ca Centre Est accelerator relying on Vandeweghe and Fu’s (2018) work. First, we distinguish three types of internal corporate accelerators: corporate coaches (mentors from corporate accelerators), founders, accelerator staff and accelerated ventures. In addition, the two accelerators mobilize two types of external stakeholders: expert partners who intervene with young ventures on different themes (such as marketing and sales, human resources, etc.) and ambassador’s partners who financially support the accelerator and collaborate with young ventures and accelerators in different projects.

Data collection

Data were collected from three main sources, interviews, observations, and secondary data, which enable triangulation (Yin, 2014) and limited retrospective bias. We selected data on BM trajectory and the context of BMI. In that respect, we triangulated at least two sources (interviews, the venture’s website, press and video excepts) to present the initial BM and BMI of young ventures as well as on the intentions of stakeholders. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with two groups (young ventures and accelerators). Thus, two distinct interview guides were used. First, we interviewed internal stakeholders of accelerators (founders and staff) and asked them about their collaboration with young ventures and external stakeholders. Then, we asked representatives of the ventures about their activities and BM. Then, we questioned their interactions and collaborations with internal and external accelerator stakeholders and what changes were made to their initial BM. In this study, we did not interview external stakeholders of accelerators, which represents one of the limits of this research. Consequently, we rely only on the perspective of young ventures. The interviews were conducted between winter 2017 and autumn 2019 in Village by the CA Normandy accelerator, and they were conducted mostly in autumn 2019 in Village by the CA Centre East accelerator. We ended up with 35 semi-structured interviews, and each interview was recorded and transcribed, lasting between 30 minutes and 1 hour. The interviews were used to determine the influence of stakeholders as well as the intention of young ventures’ stakeholders in terms of BMI. In addition to interviews, several observation days were conducted at both accelerators. Observations provide valuable information to perceive informal interactions between stakeholders and young ventures’ management teams and the impact on BMI. Finally, we use websites, documents, corporate presentations (such as detailed business plans or strategy-formulation documents), and archival data, including firms’ websites, press coverage, blogs, and video excerpts to check the different constitutive activities and their linkages for the final BM.

Data analysis and coding

We analysed each corporate accelerator separately to provide comprehensive insight into the role of its stakeholders and the BMI of each venture. First, we wrote narrations for each venture’s case and then determined whether the initial intention of managers was to explore or exploit. Second, we identified and coded the BM elements (content, governance, and structure) of each venture and their evolution according to an activity system perspective (Zott and Amit, 2010). This perspective is used to understand how entrepreneurs develop a new logic of creating value through opportunities in the interaction of their ecosystem. Third, we assessed whether BMI occurs as one of the 3 following elements: adding new activities (novel content), bringing in new partners to perform specific activities (novel governance) and linking activities in novel ways (novel structure).

Regarding exploration and exploitation, we relied on Benner and Tushman’s (2003) and Osiyevskyy and Dewald’s (2015) differentiation:

The intention was characterized as exploratory, as managers were targeting new types of customers, mobilizing new resources and competences, developing new capabilities and experimenting. These activities bring new ways to create value and offer completely new products and services that imply the design of new sets of activities.

The intention was characterized as exploitative, as managers were targeting existing customers and were using existing resources and competences to refine them or recombine them to extend services and products.

Table 2

Cases and number of interviews (1)

Table 2

Cases and number of interviews (2)

Table 3

Coding of initial BM

Table 4

Coding of BMI and the intention of exploration and exploitation

Finally, we identified corporate accelerator stakeholders and coded the interview quotes that refer to their role in young ventures’ BMI. We relied on the research in Rydehell (2020) on the role of stakeholders and transfer to the particular context of accelerators. To limit the bias of founders’ perceptions of the different roles of stakeholders, we questioned and confirmed the information with other cofounders or employees. First, position refers to the value and place of stakeholders, such as clients, suppliers, or complementors, in the network. Task refers to the function accomplished in that position: codevelopers, evaluators, advisers, providers and connectors as defined in the literature review.

We tracked the changes in different BM elements as well as in their interdependence in each venture after entering the accelerator. Furthermore, we note whether and why one of the accelerator stakeholders was involved and the role by which that involvement influenced the young venture’s BM. Then, we conducted cross-case analysis to identify common patterns among the different young venture cases and between the two corporate accelerators in terms of the role of stakeholders (Who are they? What are their positions and tasks?) and their influence on young ventures’ BMs (When, why, and how have they spurred young venture BMI?).

Table 5

Coding of roles of corporate accelerator stakeholders

Results

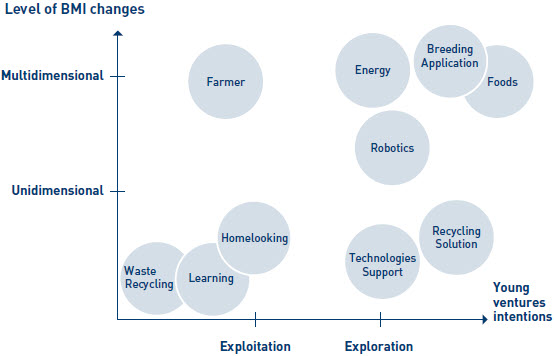

In the first part, we carry out an intra-case analysis and choose to describe 4 cases, which are particularly representative of the following situations (see figure 2):

young ventures, which intend to explore new activities and end up changing only one dimension of their BM;

young ventures, which intend to explore new activities and actually transform several dimensions of their BM;

young ventures, which wanted to exploit and actually modify only one dimension of their BM;

young ventures, which wanted to exploit and end up transforming several dimensions of their BM.

We explain the role of internal and external stakeholders for each case and how their interactions with the young venture shape BM.

In the second part, we conduct inter-case analysis and explain the expectations of young ventures in terms of BMI when they were joining the corporate accelerator, and we differentiate between the roles and tasks of stakeholders for different BMIs.

Figure 2

Representation of the different case intentions and BMI levels

Description and analysis of 4 representative cases

Exploration intention leading to one BM’s dimension change

Technologies Support ventures operate in big data and digital transformation and conduct three main activities: research and development through big data, software production and consulting. As it joined the accelerator, Technologies Support expected to explore new opportunities by using data from connected objects, which are increasingly being used in the agricultural industry. It collaborated with an internal stakeholder (one of the accelerator’s founders) to generate new services using those data. However, the venture did not have the same vison as that stakeholder who wanted to act as codeveloper in the R&D program instead of buying the solution from the start-up; therefore, their collaboration ended, as described in the following quote:

“We had also worked with a venture that works on big data to effectively give it a background … that could lead to develop solutions adapted to agriculture … it did not work because, in fact … we came to outsourcing and we cannot do that… We work only on collaborative projects”

Internal stakeholder from Village by CA Normandy

Later, Technologies Support codeveloped a new product with another venture (Robotics venture), which was hosted in the accelerator. However, the two ventures did not find clients for that product and abandoned the project.

Accordingly, the exploration activities of technological support in a new industry failed. Nevertheless, the venture optimized its initial BM by collaborating with external stakeholders that acted as providers of know how to improve its operational activities (accounting, marketing, human resources) and to streamline the relationships among the different activities of its BM.

This case shows that the interaction with corporate accelerator stakeholders orients young venture intentions. Thus, primarily discussions with internal stakeholders aimed at exploring opportunities in a new industry are demonstrated in the following quote:

“This is typically a company working on the smart city, you must explain to it that it has a potential market in connected agriculture … that is why we are in the process of setting up interviews with farmers to bring up needs to give them back to the young ventures and make them want to invest in that.”

Internal stakeholder from Village by CA Normandy

However, exchanges of knowledge on the new field to explore (here, the agriculture industry) as well as divergences in the role of different stakeholders interfere with the reconfiguration of their BM. The corporate accelerator still provides value to young ventures by fostering connections with external stakeholders that bring resources such as information to improve the current operations of the BM. Thus, BMI is punctuated with interactions with different types of stakeholders that outline challenges of exploration activities and new opportunities for improving a single dimension of the BM.

Exploration intention leading to the transformation of several BM dimensions

Breeding application ventures are a subsidiary of an Indian company that develops technologies in the dairy sector to improve the agro-dairy supply chain, in particular milk production, milk supply and cold chain. An Indian company that was already selling the solution in its domestic market conceived the initial BM. An initial application was designed, and as this company wanted to enter the French market, a new venture was set up and hosted in the accelerator. Soon after having joined the accelerator, the managers of the Breeding Application collaborated mainly with internal stakeholders, which acted as evaluators, advisors, and connectors. Breeding Application conducted only exploration activities to define a new BM for its breeding solution. Relationships with stakeholders allowed the young venture to test its solution in real conditions through a network of more than 300 farms, which presented potential customers to the venture. Their collaboration further enhanced the venture’s understanding of customer needs and provided several insights into potential changes to the value proposition of the young venture. In addition to helping the young venture to test its solution and to gain an understanding of customer needs, collaboration with the accelerator’s founders enabled the validation and recognition of the venture’s offerings among future customers.

The involvement of internal stakeholders allows continuous changes mainly related to the model of revenue and product adjustment. These changes lead to a reconfiguration of the initial BM through several modifications and adjustments. For instance, Breeding Application’s managers adopted a monthly subscription as a revenue model (novel content), which involved establishing a new partnership with a local technology support system and a bank (novel governance), as demonstrated in the following quote:

“We did not know if we install the solution and then ask for a subscription to cover the costs of the internet and the cloud. … Finally, we realized that all the start-ups that have this kind of technology ask a subscription every month. We oriented on it”

Manager of Breeding Application

Furthermore, to reconfigure its activities, the venture also reprioritized its core and peripheral activities according to the options offered by its product (novel structure). The analysis of that case shows that such companies often need to test and validate their solutions and prototypes in real conditions and with their clients. In that respect, internal stakeholders assume the role of evaluators and further enhance the venture’s understanding of customer needs. They also provide insights into potential changes to the value proposition of young ventures. For instance, as the Breeding Application tested its BMI on several farms, it enabled the validation and recognition of the venture’s offerings among future customers through interactive exchanges, as demonstrated in the following quote:

“They truly helped us; there were many exchanges between us to say … now, we have a real document that we can use for other customers.”

Manager of Breeding Application

Thus, BMI is characterized here by frequent and iterative exchanges with internal stakeholders to first define certain elements of BMI. New knowledge generated led the new venture to amend several other elements of the BM and to envision more radical transformations of the BM.

The analysis presented below reveals that while some stakeholder roles concern more exploitative activities and other roles promote the explorative activities of mature ventures that want to explore new opportunities in their own industry or in new ones.

Exploitation intention and one BM dimension modification

Homelooking represents a platform for relocation specializing in the mobility of employees, new hires and training students. It works either with companies whose employees are travelling and need to be relocated or directly with the beneficiaries. It integrated the accelerator to improve existing activities to strengthen its initial BM to obtain access to strategic partners of the accelerator. Homelooking faced difficulties in terms of human resources and the structuration of their activities. In that respect, managers of the venture discussed with internal stakeholders that acted as advisors but also as connectors by connecting the young venture to other ventures that had also been accelerated. These ventures can be considered external stakeholders. Through their interactions, venture Homelooking improved its operational activities and the linkage among the BM’s activities.

Furthermore, internal stakeholders connected the young venture to external stakeholders (ambassador partner), which provided accommodations (key resources) enabling the venture to target and satisfy new customer segments. Moreover, resources provided by the latter stakeholders and advice from internal stakeholders enabled the young venture to deploy exploitative BMI (new resources).

Thus, BMI is characterized by an intent of the young venture’s management to improve its operations and specific roles from both internal and external stakeholders. Internal stakeholders provide advice for young ventures about their new value proposition and how they may link their new activities. Furthermore, such BMI can also emerge from interactions among accelerated (or formerly accelerated) young ventures, which exchange advice about operational activities, expertise and experiences.

Exploitation intention leading to the modification of several BM dimensions

Farmer is a rental platform to exchange agricultural equipment among farmers. That platform allows the owners of those unused equipment to generate additional income through the rental of their unused machines and users to have access to agricultural equipment at low prices. It joined the accelerator to gain credibility and validation for its initial BM in the agricultural market. However, the venture spurs BMI through continuous modification and the addition of novel elements to the initial BM. During its acceleration process, the venture obtained financing from an internal stakeholder who acted as provider of finance and entered into its capital. Then, that stakeholder acted as connector and advisor by enabling the venture to communicate about its solution to technicians and farmers and receiving feedback.

Hence, Farmer identified and integrated a new value proposition to its initial BM. The first value proposition consisted of creating ads to connect investors in agricultural machinery. The second relevant value proposition dealt with finding farmers to carry out specific duties.

Furthermore, Farmer collaborated with external stakeholders of the accelerator to obtain new know-how about the development of commercial activities. Through this collaboration, Farmer developed another value proposition to offer a monthly stipend to students, farmers and other employees in the agricultural industry to visit farmers and identify unused machines and then register them on the platform by creating new announcements.

Thus, Farmer spurred BMI through the involvement of internal and external stakeholders, continuous modifications and the addition of novel elements to the initial BM. The Farmer venture combined a new value proposition (novel content) for the agricultural industry, the creation of an ambassador network (novel governance), and new links among activities (novel structure).

BMI involving the transformation of several dimensions of the current BM of the young venture comes both from the first intent of the new venture to add new dimensions to its existing BM and from interactions with different types of both internal and external stakeholders.

Table 6

Description of young ventures’ initial intention and corporate accelerators’ stakeholders’ roles and influence BMI (1)

Differences in terms of young ventures intents

As apparent in the description of the four cases in the previous part, the intent of young venture management differs as they join the accelerator. Thus, certain ventures focused on exploitative activities. It concerns venture Learning and venture Homelooking. These ventures did not intend to bring in novelty and, instead, sought to improve the same BM. They focused on the efficient execution of their activities rather than the introduction of novel features, as explained by the founder of Homelooking (a relocation platform specializing in employee mobility):

“If today I can do what I do well, it will be pretty good… Before I explore other things, I would like to do what I do well.”

Manager of Homelooking

As described in the quote, the young ventures’ management team attempted to improve existing activities to strengthen its existing BM. Similarly, as described in appendix 1, quote V3, in case Learning, the young ventures mostly wanted to connect to clients but did not manage to obtain access to successful relationships. In contrast, other ventures may seek a broader range of services, such as in Technologies Support. That venture integrated the accelerator both for accommodation, to obtain access to technical know-how to conduct and structure their operational activities and to evaluate opportunities to launch new products for the agricultural industry:

“… In the agriculture industry, as there are more and more connected objects, inevitable we will recover data and therefore questions arise: What we will do with this connected data we may resell them or create more value by generating new services around it.”

Manager of Technologies Support

Then, the intercase analysis reveals that young ventures not only search for resources, as suggested by Rydehell (2020) but also validate their BM and obtain access to a large network of contacts and sometimes to an ecosystem. Here, we can also differentiate between the cases that were first aimed at exploring and those that had an objective of exploiting their current BM. Thus, as described in Table 5, young ventures that wanted to exploit were mainly interested in the potential clients or investors with which the accelerator could connect them. Thus, quotes [V2] and [V3] of appendix 1 relative to ventures Waste Recycling and Learning show their limited perception of the accelerator’s network by focusing only on investors or clients. Then, those connections allow both validating the value proposition and obtaining complementary contacts by conveying a positive image of the company. In a different way, young ventures that wanted to explore new activity were looking for recognition in the new domain and/or to access a broader ecosystem composed of customers but also suppliers and partners, as demonstrated in appendix 1, quotes [V10] relative to Energy. Another example relates to venture Farmer, which needed to gain access to the agricultural market to develop its platform and to increase the credibility of its initial BM, as the founder explains in this quote:

“… Market access proof the concept (Initial BM), last point is to try to find and finance the ways to accelerate…”

Founder of Farmer

Similarly, venture H initiated a new project with one of the internal stakeholders to obtain a label for its project, which would be recognized by a large community in connected agriculture:

“… We needed help with the label … to place the TES brand name, because it is a digital IT project in keeping with the times … because it is a long-term product.”

Project manager in Recycling Solution

The case descriptions show that even though young ventures could have similar intent to either exploit their current BM or explore new activities, the result may differ in terms of transformations of BMI (either a single dimension or several dimensions). Consequently, we further explored the role of stakeholders in BMI to understand those differences.

Differences in terms of stakeholders’ roles

Stakeholders play different roles in BMI. Thus, we find that as BMI undergoes a change of a single dimension, stakeholders take traditional roles of providers and codevelopers, whereas changes in several dimensions involve more complex and new roles, such as evaluators and providers of finance.

First, for young ventures that went through limited changes in their BM, the roles played by stakeholders were mostly those of product/service providers, know-how suppliers and codevelopers. First, resources that were supplied by stakeholders enable young ventures to increase their operational efficiency. For instance, accommodations were provided by a stakeholder in venture Homelooking, enabling this venture to target and satisfy more customer segments:

“[One of accelerator’s stakeholders] provides me with apartments when we want to relocate people … which allows us to satisfy more our customers and expand to other segment (Business customer).”

Manager of Homelooking

Moreover, external stakeholders, called “expert partners”, help young ventures develop different themes, such as low, marketing and business plans. Here, external consultants or experts provide mainly technical knowledge and ideas to young ventures about how to conduct and structure their exploitative activities, as demonstrated in quotes [V6] in appendix 1 relative to Technologies Support. Both accelerators mobilize employees and managers (mentors) from the “Credit Agricole Bank” to assume the role of know how provider. Nevertheless, young ventures in this category sometimes find that they did not have enough interactions with internal stakeholders for them to fully grasp their needs and connect them to relevant providers.

Then, corporate accelerator stakeholders create innovative new products or services as codevelopers. Here, young ventures collaborate with established companies to improve their existing products or develop a new product. However, those developments lead to limited changes to the BM, which mainly focus on refining the value proposition. For instance, in Robotics, an R&D partnership was established with internal stakeholders (founder of Village by CA Normandy accelerator) to develop a new product.

“We have had an R&D partnership with [Agrial] over 3 years… It is a product that has already been manufactured… We finished the adjustments and tested the tools with [Agrial]”.

Manager of Robotics

What is particularly interesting here and new compared to existing work is that the role of codeveloper can be taken by external stakeholders and more particularly portfolio companies (young ventures, which are co-fostered in the accelerator). As young ventures often lack finance to develop a new product or service, they collaborate with each other to develop solutions, share risk and resources and competences. That is the case of Robotics, which started collaboration with venture Technologies Support to develop a new product.

“… We have already done, in our side, on many things, and we are trying to have funding to be able to launch the experimentation… I do not know yet in what form (we will commercialize it). We are waiting to see if our vision is the right one or not, as we have not yet tested the tool…”

Manager of Technologies Support

As demonstrated in the former development as well as in the description of Technologies Support and Homelooking, both internal and external stakeholders are involved in the exploitative transformation of BM (a single dimension) (see quotes [V6] and [V4]). Those stakeholders intervene in specific topics, mostly as providers of resources and know-how, advisors or codevelopers. More complex transformations of BM (impact several dimensions) still involve the role of codevelopers and advisors, but stakeholders are providers of finance and evaluators and help commercialize new products. Furthermore, a single stakeholder can take several roles as the relationships with the young venture evolve, as demonstrated in quote [V8] for Robotics in appendix 1.

Comparing the cases shows that in addition to codeveloping and evaluating young ventures’ value propositions, internal stakeholders contribute to young ventures’ explorative activities by providing financial assets. These assets allow them to develop new products and services. For instance, Food first received financing from corporate stakeholders and developed a new way to produce and commercialize their products (see quotes [V9] in appendix 1). Similarly, Farmer received a first round of financing from a corporate stakeholder that entered its. Farmers involved the deployment of a new service to rent agricultural machines that are not actively being used by farmers (see quotes [V5] in appendix 1). In addition, Energy obtained access to funding, though an external stakeholder thanks to accelerator involvement (see quotes [V1] in appendix 1).

As they bring capital, stakeholders often provide more specific advice for young ventures about their new value proposition and how they may link their new activities. The following quote shows the interrelationships between the two roles taken by the stakeholders and the fact that the results were obtained faster than if the stakeholder was not financially involved:

“We are currently building with [the stakeholder] an offering for electricity supply.… The fact that they provided capital and the relationship that we have today accelerated establishing this [new] activity…”

Founder of Energy

Moreover, our results also show that the advisor role can be taken by internal stakeholders (large companies):

“At the beginning we said our solution does that. Then, through our discussion, they were only interested in 2 or 3 options on our solution. So, we started to communicate only on these options … that allowed us also it truly does allow to have customer feedback.”

Manager of Breeding Application

Then, the role of the connector is assumed by both internal and external stakeholders. Internal and external networks of the accelerator are here interrelated. Hence, the peculiarity of the two accelerators is the fact that each accelerator can obtain access to the regional ecosystem of the other accelerators, which belong to the “Credit Agricole” network of accelerators. In addition to global networking activities, the accelerators from this network provide transit offices across the world for all young ventures belonging to Village by the CA network. The following quote shows the interrelation within those different ecosystems:

“We connect [managers of Farmer] with our partner [external stakeholder] … to develop the commercial aspect of his activity…. they decided together to target farmers involved and to use the platform to turn them into ambassadors of the company, they would propose to other farmers to join and use the apps…”

An internal stakeholder from Village by CA Normandy

Finally, our results highlight a new role of stakeholders in the accelerator context. They show that corporate coaches may play the role of distributors, helping young venture sales and commercializing their product through their network. The following quote describes how technicians, employees of stakeholders, participate in the commercialization of young venture products:

“ … the first stage of partnership has been to promote the solution through all of [this stakeholder]’s means of communication, in particular through the many territories they have divided into several cooperatives. We spoke to all the small agricultural cooperatives …. Then, it was an element of access to the market via the team of technicians, it has 200 technicians, and we trained these technicians on the solution and on the fact that they could propose this solution to farmers.”

Founder of Farmer

To synthetize, the results reveal that under the influence of corporate accelerator stakeholders, young ventures’ BM evolves, although a series of transitions in which various accelerator stakeholders continually shape their initial BM under different interactions and actions. Thus, the level of change in BMI depends not only on the initial orientation in terms of exploration and exploitation of the young ventures’ founders but also on interactions with stakeholders.

Discussion and conclusion

This study aims to explore BMI in young ventures hosted in corporate accelerators. We began our research by questioning the roles that corporate accelerator stakeholders have in young ventures’ BMI and how these roles impact ventures’ BM in terms of exploration and exploitation. Our longitudinal multi-case study has shed light on the influence of stakeholders in the final level of novelty of the BMI and on the functioning of corporate accelerators.

Thus, Snihur and Zott (2020) emphasize the need for more research on young ventures’ BMI. Those authors particularly demonstrate that the orientation of the founder in terms of novelty and the influence of its team explain the development of either explorative or exploitative BMI. Our research brings a more nuanced perspective. Thus, we recognize that the founder’s orientation is one explanatory factor, but we also consider the influence of stakeholders. As a consequence, the founder may intend to deploy exploitative or explorative BMI, but interactions with stakeholders may reshape the trajectory of the BMI. Two main situations can be differentiated. First, founders have an orientation towards exploration, and as proposed by Snihur and Zott (2020), they carry out research in other industries. However, we find that as those founders interact with stakeholders, they may determine that those latter had a lower interest in their BMI than expected. Those founders were, then, not flexible enough to adapt several dimensions of their BM and abandon their initial plan to embrace explorative BMI. In contrast, founders may have an intent to deploy exploitative BMI. They carry limited industry search but ended up deploying exploratory BMI as they envision a large scope of opportunities thanks to stakeholders and successively transform several dimensions of their BMI. Thus, our work completes the conclusion of Snihur and Zott (2020) by highlighting the influence of stakeholders in developing systemic thinking. We bring new insight by showing that stakeholders can help founders identify the sources of novelty in their BM and that founders should also understand how their BMI fits with the BM of the stakeholders they want to interact with as they intend to deploy explorative BMI.

Furthermore, our results complete also the work of Garreau et al. (2015) about the implementation of BMI by showing the role of stakeholders in this process. In addition, we extend the work on the role of corporate accelerator ecosystems. Thus, Vandeweghe and Fu (2018) propose different roles for accelerator stakeholders. We highlight several dimensions that can explain the influence of accelerator stakeholders on the level of novelty of young ventures’ BMI.

First, young ventures, which amend several dimensions of their BM, tend to work with more stakeholders. In that respect, our research shows that young ventures’ BMs change as the process of cocreation by establishing co-development relationships between young ventures and corporate accelerators’ stakeholders (Chesbrough and Schwartz, 2007). Indeed, collaboration with accelerator stakeholders from established companies provides new resources (knowledge, information, financial assets) for young ventures. They also enable young ventures to test and validate their solution. Developing products with those corporations assures product concept validation for future customers. In addition, resources provided by stakeholders enable a young venture to modify elements of its BM. In particular, the interplay between stakeholders and young ventures can also shape the value proposition of the BMs of young ventures.

Second, according to their status and roles, stakeholders foster different orientations. Thus, we demonstrate that established companies that play the role of corporate coaches and ambassadors support mainly young venture exploration activities as codevelopers, suppliers of finance and evaluators. These roles spur BMI through significant changes in one or several elements of young venture BM. On the other hand, internal and external stakeholders mostly support young venture exploitation activities by enabling the refinement of their initial BMs. They are then mostly providers of resources and know-how, advisers and codevelopers.

Third, the role of corporate coaches and ambassador partners should evolve over time. Thus, new BMI, which depicts a high level of novelty, is often associated with the fact that corporate coaches, ambassador partners and portfolio companies play different roles and even new roles, which have not been highlighted in the literature previously. We particularly identified the role of distributors that may promote and buy young ventures’ services and the role of codevelopers attributed to young ventures, which collaborate with each other around the development of solutions by sharing risk as well as resources and competence.

However, our work also shows that a strict definition of the role of internal stakeholders, which would be formally defined into the governance of the corporate accelerator, may limit the ability of new ventures to deploy a high level of change in their BMI. Thus, young ventures have limited resources and tend to rely on internal stakeholders of the accelerator to explore new markets and technology. As internal stakeholders cannot take on new roles to adapt to the needs of young ventures, it can negatively impact the ability of the founder to deploy BMI with a high level of novelty. Consequently, our conclusion contributes to work on corporate accelerators (Moschner et al., 2019) and demonstrates the need for accelerators to select young ventures with an orientation towards exploration or exploitation, which corresponds to accelerators, as those orientations imply different roles from accelerator stakeholders.

Furthermore, a high level of novelty in BMI was often associated with the involvement of stakeholders as providers of finance as well as codevelopers and evaluators. In those instances, stakeholders take an active part in the decision process concerning the BM. They both shape the value proposition by adding or dropping proposals and define new ways to organize the value chain and network. Crucial decisions concerning BMI are then made in concertation between stakeholders and founders. Thus, the power associated with decision shifting from founders to the accelerators’ stakeholders. This result is different from that of Snihur and Zott (2020), which emphasizes the centralization of power from founders in explorative BMI. It also extends the work by Rydehell (2020) by highlighting the fact that stakeholders’ interactions not only shape founders’ perceptions about BMI but also directly deter the consideration of some options.

Finally, accelerators have been demonstrated to help founders overcome bounded rationality challenges by increasing the amount of information search at the beginning of the process (Cohen et al., 2019). We can extend those results by showing that different types of information should be provided by different types of actors. Thus, none of the young ventures that we are studying develop only explorative BMI. Those young ventures involved in exploration also intend to improve their BM at the same time. Thus, information should be provided on how to refine existing activities and simultaneously explore new avenues and transform the value proposition. This implies the involvement of different stakeholders early in the process and concurrently. This result also sheds new light on the debate on how young ventures should carry out exploitative and exploratory BMIs (Smith et al., 2010; Sosna et al., 2010). The separation of activities with different networks of stakeholders having different roles can provide a future area for debate. These networks can also shape the learning process of young ventures. In this sense, we show that corporate accelerators provide capacities to young ventures to identify or create opportunities not only through access to information received and the interpretation of this information but also through learning. These stakeholders can strengthen young venture capacity to seize opportunities. We have observed this contribution in particular in the relations between corporate founders of Village by Ca Normandy accelerator through Agri’up programme.

Our research has two main implications for managerial practice. First, accelerators currently face difficulties customizing and adapting their support for each young venture because they lack guidance and references on the subject. In this sense, accelerator managers try to propose personal support for each venture. At the same time, they point out the difficulties, for example, mobilizing the same stakeholders for the same venture or organizing a common seminar that will interest a large group of ventures.

Hence, our research suggests that support programs should be customized based on the needs of young ventures relative to the explorative and/or exploitative activities they are undertaking. For instance, young ventures in the exploration phase need to evaluate and codevelop their offerings with relevant partners, while young ventures in the exploitation phase need more advice and know-how about their operational activities.

Our findings offer practical implications concerning the role of stakeholders and their position in young venture BMI. This may help both accelerators and young ventures identify and consider stakeholders in terms of their roles and potential contributions to BMI. By doing so, young ventures can reduce the time, cost and energy they expend establishing relationships.

Although we provide insight into the role of stakeholders in BMI, like all research, this study has limitations that offer a novel direction for future research. First, we focus on our research only on the perspective of young ventures and internal stakeholders, and we do not extend the stakeholder view. Then, our empirical study was restricted to two corporate accelerator cases from the Village by CA Network, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the wider context of corporate accelerators, especially corporations that are adopting different forms and approaches in designing their acceleration programs (Hochberg, 2016). Future research should therefore study other accelerators to extend the current insights.

Moreover, our research focuses on young ventures’ BMI, which differs from the business innovation of established companies. Consequently, stakeholders’ roles in established companies may be fundamentally different than those in young ventures, and future research can investigate this question, especially in the accelerator context.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Amina Hamani is a postdoctoral researcher at the Ecole des Mines de Saint-Etienne and an associate researcher at the University of Caen. She holds a PhD in Management Sciences from the University of Caen. Her research focuses on business models, ecosystems and digitalization.

Fanny Simon is a Full Professor at the University of Caen Normandy. She works in the NIMEC laboratory and carries out research on innovation, creativity and project teams. She has published her work in several journals and notably the European Management Journal, M@n@gement, the Revue Française de Gestion and Management International.

Bibliography

- Abdelkafi, N.; Makhotin, S.; & Posselt, T. (2013). “Business model innovations for electric mobility—what can be learned from existing business model patterns?”, International Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 17, No 01, p. 1-41.340003.

- Alkhanbouli, A.; Estay, C.; & Tsagdis, D. (2020). “Modèles d’affaires et modèles d’affaires innovants au sein des zones franches: une approche qualitative ”. Management international, Vol. 24, No 1, p. 97-108

- Banc, C.; Messeghem, K. (2020). “Discovering the entrepreneurial micro-ecosystem: The case of a corporate accelerator”, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 62, No 5, p. 593-605.

- Benner, M. J.; Tushman, M. L. (2003). “Exploitation, Exploration, and Process Management: The Productivity Dilemma Revisited”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28, No 2, Academy of Management, p. 238-56.

- Chesbrough, H.; Schwartz, K. (2007). “Innovating Business Models with Co-Development Partnerships”, Research-Technology Management, Vol. 50, No 1, p. 55-59.

- Cohen, S. L.; Bingham, C. B.; & Hallen, B. L. (2019). “The role of accelerator designs in mitigating bounded rationality in new ventures”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 64, No 4, p. 810-854.

- Connelly, B. L.; Shi, W., Hoskisson, R. E.; Koka, B. R. (2019). “Shareholder influence on joint venture exploration”, Journal of Management, 2019, Vol. 45, No 8, p. 3178-3203.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). “Building Theories from Case Study Research”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 4, Academy of Management, p. 532-50.

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2017). “Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation: How Far Have We Come, and Where Should We Go?”, Journal of Management, Vol. 43, No 1, p. 200-227.

- Garreau, L.; Maucuer, R.; & Laszczuk, A., (2015), “La mise en oeuvre du changement de business model. Les apports du modèle 4C”, Management international, Vol. 19, No 3, p. 169-183.

- Hampel, C. E.; Tracey, P.; & Weber, K. (2020). “The art of the pivot: How new ventures manage identification relationships with stakeholders as they change direction”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 63, No 2, p. 440-471.

- Hochberg, Y. V. (2016). “Accelerating Entrepreneurs and Ecosystems: The Seed Accelerator Model: The seed accelerator model”, Innovation Policy and the Economy, Vol. 16, No 1, p. 25-51.

- Kohler, T. (2016). “Corporate Accelerators: Building Bridges between Corporations and Startups”, Business Horizons, Vol. 59, No 3, p. 347-57.

- Kringelum, L. B.; Gjerding, A. N. (2018). “Identifying Contexts of Business Model Innovation for Exploration and Exploitation Across Value Networks”, Journal of Business Models, Vol. 6, No 3, p. 45-62.

- Lubik, S.; Garnsey, E. (2016). “Early Business Model Evolution in Science-Based Ventures: The Case of Advanced Materials”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 49, No 3, p. 393-408.

- Marion, T. J.; Eddleston, K. A.; Friar, J. H.; & Deeds, D. (2015). “The Evolution of Interorganizational Relationships in Emerging Ventures: An Ethnographic Study within the New Product Development Process”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 30, No 1, p. 167-84.

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C. L.; & Afuah, A. (2017). “A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research”, Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 11, No 1, p. 73-104.

- Mehrizi, M. H. R; Lashkarbolouki, M. (2016). “Unlearning troubled business models: from realization to marginalization”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 49, No 3, p. 298-323.

- Miles, M. B.; Huberman, A. M. (2003). Analyse des données qualitatives, De Boeck Supérieur

- Miller, K.; McAdam, M.; & McAdam, R. (2014). “The Changing University Business Model: A Stakeholder Perspective: Changing University Business Model”, R&D Management, Vol. 44, No 3, p. 265-87.

- Moschner, S. L.; Fink, A. A.; Kurpjuweit, S.; Wagner, S. M.; Herstatt, C. (2019). “Toward a better understanding of corporate accelerator models ”, Business Horizons, Vol. 62, No 5, p. 637-647.

- Moyon, E. & Lecocq, X., (2014), “Rethinking Business Models in Creative Industries: The Case of the French Record Industry”, International Studies of Management & Organization, Vol. 44, No 4, p. 83-101.

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Dewald, J. (2015). “Explorative Versus Exploitative Business Model Change: The Cognitive Antecedents of Firm-fLevel Responses to Disruptive Innovation”, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Vol. 9, No 1, p. 58-78.

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Dewald, J. (2018). “The pressure cooker: When crisis stimulates explorative business model change intentions ”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 51, No 1, p. 540-560.

- Pauwels, C.; Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; & Van Hove, J. (2016). “Understanding a New Generation Incubation Model: The Accelerator”, Technovation, Vol. 50-51, p. 13-24.

- Reymen, I.; Berends, H.; Oudehand, R.; & Stultiëns, R. (2017). “Decision Making for Business Model Development: A Process Study of Effectuation and Causation in New Technology-Based Ventures: Decision Making for Business Model Development”, R&D Management, Vol. 47, No 4, p. 595-606.

- Richter, N.; Jackson, P.; & Schildhauer, T. (2018). “Outsourcing Creativity: An Abductive Study of Open Innovation Using Corporate Accelerators”, Creativity and Innovation Management, Vol. 27, No 1, p. 69-78.

- Rispal, M. H. (2002). “La méthode des cas”, De Boeck Supérieur.

- Ruiz-Ortega, M. J.; Parra-Requena, G.; García-Villaverde, P. M.; & Rodrigo-Alarcon, J. (2017). “How does the closure of interorganizational relationships affect entrepreneurial orientation?.”, BRQ Business Research Quarterly, Vol. 20, No 3, p. 178-191.

- Rydehell, H. (2020). “Stakeholder roles in business model development in new technology-based firms”, International Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 24, No 04, p. 1-38

- Scillitoe, J. L.; Chakrabarti, A. K. (2010). “The role of incubator interactions in assisting new ventures”. Technovation, Vol. 30, No 3, p. 155-167.

- Simon, F.; Tellier, A. (2011). “How do actors shape social networks during the process of new product development?”, European Management Journal, Vol. 29, No 5, p. 414-430.

- Sinha, S. (2015). “The Exploration—Exploitation Dilemma: A Review in the Context of Managing Growth of New Ventures”, Vikalpa, Vol. 40, No. 33, SAGE Publications India, p. 313-323.

- Smith, W. K.; Binns, A.,; Tushman, M. L. (2010). “Complex business models: Managing strategic paradoxes simultaneously”, Long range planning, Vol. 43, No 2-3, p. 448-461.

- Snihur, Y.; Wiklund, J. (2019). “Searching for Innovation: Product, Process, and Business Model Innovations and Search Behavior in Established Firms”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 52, No 3, p. 305-25.

- Snihur, Y.; Zott, C. (2020). “The Genesis and Metamorphosis of Novelty Imprints: How Business Model Innovation Emerges in Young Ventures”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 63, No 2, p. 554-583.

- Sosna, M.; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R. N.; & Velamuri, S. R. (2010). “Business Model Innovation through Trial-and-Error Learning”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No 2-3, p. 383-407.

- Toulouse, J. M.; & Bourdeau, G. (1995). “Taux de croissance et stratégies des nouvelles entreprises technologiques”. Perspectives en management stratégique, Economica, Vol. 3, p. 365-392.

- Usman, M.; Vanhaverbeke, W. (2017). “How start-ups successfully organize and manage open innovation with large companies”, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 20, No 1, p. 171-186.

- Vandeweghe, L.; Fu, J. Y. T. (2018). “Business accelerator governance”. Accelerators. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Warnier, V., Lecocq, X., & Demil, B. (2018). “Les business models dans les champs de l’innovation et de l’entrepreneuriat: Discussion et pistes de recherche”, Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat, Vol. 17, No 2, p. 113-131.

- Wilden, R.; Hohberger, J.; Devinney, T. M.; & Lavie, D. (2018). “Revisiting James March (1991): whither exploration and exploitation?”, Strategic Organization, Vol. 16, No 3, p. 352-369.

- Winterhalter, S.; Wecht, C. H.; & Krieg, L. (2015). “Keeping reins on the sharing economy: strategies and business models for incumbents”, Marketing Review St. Gallen, Vol. 32, No 4, p. 32-39.

- Yin, Robert K. (2014). Case study research: design and methods. Fifth edition, Los Angeles: SAGE

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. (2010). “Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No 2-3, p. 216-226.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Amina Hamani est chercheure en postdoctorat à l’Ecole des Mines de Saint-Etienne et chercheure associée à l’université de Caen. Elle est titulaire d’un doctorat en sciences de gestion de l’université de Caen. Ses recherches portent sur les business models, l’écosystème et la digitalisation.

Fanny Simon est Professeur des Universités à l’UFR SEGGAT de l’Université de Caen Normandie. Elle est rattachée au laboratoire NIMEC et effectue des recherches sur l’innovation, la créativité et les équipes projet. Elle a publié ses travaux dans European Management Journal, M@n@gement, la Revue Française de Gestion et Management International.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Amina Hamani es investigadora postdoctoral en la Escuela de Minas de Saint-Etienne e investigadora asociada en la Universidad de Caen. Es doctora en Ciencias de la Gestión por la Universidad de Caen. Su investigación se centra en los modelos de negocio, el ecosistema y la digitalización.

Fanny Simon es profesora titular en la Universidad de Caen Normandía. Trabaja en el laboratorio NIMEC y realiza investigación sobre innovación, creatividad y equipos de proyecto. Ha publicado su trabajo en varias revistas y, en particular, European Management Journal, M@n@gement, Revue Française de Gestion y Management International.

List of figures

Figure 1

General model of young ventures’ BMI process in an accelerator context

Figure 2

Representation of the different case intentions and BMI levels

List of tables

Table 1

Definition of initial BM and BMI

Table 2

Cases and number of interviews (1)

Table 2

Cases and number of interviews (2)

Table 3

Coding of initial BM

Table 4

Coding of BMI and the intention of exploration and exploitation

Table 5

Coding of roles of corporate accelerator stakeholders

Table 6

Description of young ventures’ initial intention and corporate accelerators’ stakeholders’ roles and influence BMI (1)

10.7202/1069097ar

10.7202/1069097ar