Abstracts

Abstract

Providing different creative approaches and involving different players, opposite worlds co-exist within a creative industry. Nevertheless, surprising collaborations occur between these worlds. Based on an in-depth exploratory study in the perfume industry, this paper analyzes how designers can create differently in such opposite worlds. In addition to the social and conventional dimensions, we show that these opposite worlds are structured by differences in industry organization, distribution systems and creation processes. We propose the notion of contextual creativity: it means that creators’ creativity is embedded in a specific context. We identify a specific kind of collaboration between opposite worlds: creative symbiosis.

Résumé

Une industrie créative peut abriter des mondes opposés, proposant des produits différents et reposant sur des acteurs différents. Néanmoins, des collaborations se produisent entre ces deux mondes. À partir d’une étude approfondie dans l’industrie du parfum, cet article analyse comment des designers créent différemment dans deux mondes opposés. En plus des dimensions sociales et conventionnelles, nous montrons que ces mondes opposés se structurent autour d’organisations, de systèmes de distribution et de processus de création différents. Nous proposons la notion de créativité contextuelle pour traduire que la créativité des créateurs s’inscrit dans un contexte spécifique. Nous identifions un type spécifique de collaboration entre mondes opposés : la symbiose créative.

Resumen

Una industria creativa puede albergar mundos opuestos, ofrecer productos diferentes y confiar en diferentes actores. Sin embargo, colaboraciones se producen entre estos dos mundos. Basado en un estudio en profundidad en la industria del perfume, este artículo analiza cómo los diseñadores crean de manera diferente en dos mundos opuestos. Además de las dimensiones sociales y convencionales, mostramos que estos mundos opuestos están estructurados por diferencias en la organización de la industria, los sistemas de distribución y los procesos de creación. Proponemos el concepto de creatividad contextual: significa que la creatividad de los creadores está integrada en un contexto específico. Identificamos un tipo específico de colaboración entre mundos opuestos: la simbiosis creativa.

Article body

Creative industries are often depicted as containing opposing worlds: independent versus commercial movies, haute cuisine versus food industry, or haute couture versus fashion industry are examples of the semantic oppositions that are found in each sub-sector (Colbert, 2003). At the industry level, these opposite worlds are manifested in the existence of two categories of actors: mainstreamers who comply with, legitimize, and reproduce the conventions of an existing art world and mavericks who do not conform to these conventions (Becker, 1982; Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016). At the organizational level, this leads to different ways of starting development processes that employ distinct creative approaches. Some organizations start by observing the dynamics in their markets—a market-driven approach, whereas others encourage talents to create without taking the market into account—a design-driven approach (Verganti, 2008, 2009).

Although ostensibly opposed, collaborations do nevertheless occur between these worlds (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016). The literature usually explains these collaborations, which may seem surprising, by mobilizing two types of explanations. Social network theorists emphasize the role of “social structures” (Becker, 1976, 1982; Cattani and Ferriani, 2008; Sgourev, 2013), while institutional scholars focus on “conventions” to analyze how actors lead to collaboration between the worlds (Rao, Monin, and Durand, 2005; Lena and Peterson, 2008).

This paper aims to contribute to this stream of research by focusing on the product development process in collaborations between opposite worlds in the creative industries. To date, we know little about what happens in terms of the development process when a creator crosses from one world to another. Such movements may seem surprising because they raise the question of these creators’ ability to operate in two worlds that rest on opposite approaches. Starting with the observation that there are collaborations between radically opposed worlds, this paper examines how and why talents are able to create differently in worlds based on different creative approaches, giving rise to very different creations.

We aim to answer this question by analyzing a particular type of collaboration between two opposite worlds in the perfume industry: on the one hand, mainstream or mass-market perfumeries, on the other hand, a niche perfumery that produces “auteur” perfumes. Part of our study focuses on Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle, a company in the second category that sells perfumes designed by some of the main perfumers from the first. In an in-depth exploratory study, we detail the development processes in these two worlds and the way the same designers operate in these two different contexts.

This research leads to three main contributions. First, it shows that these opposing worlds are not shaped solely by social or conventional dimensions. Their different approaches are embodied in each stage of the product development process. Differentiation in the industry’s creation approaches gives rise to radical differences in the development process, from its very initiation to product distribution, which explains why the same designers “change” their designs when moving from one world to the other. Accordingly, we also contribute to knowledge on creative industries by showing that the creativity—defined as a creative capability—of perfume designers (and its limitation) is determined by the multi-level context in which they work. By multi-level context, we mean the development process from its initiation to distribution and promotion, and also the general organization of the industry. Finally, we propose a new explanation, focused on the process dimension, for the collaborations between different worlds and the movement of creators (crossovers) from one world to another.

The paper starts with a review of prior literature that reflects both the opposition and collaboration between two different worlds in creative industries. Following an analysis of the two development processes, we present the results and discuss the “polarization” of the industry, the need to consider different levels of analysis (industry, process and creator) that prove to be intertwined, and we propose the concept of “creative symbiosis” to account for the singularity of the situation. Finally, this article concludes with some limitations and suggestions for further research.

Collaborations Between Worlds in Creative Industries

Creative industries, defined as “those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent” (DCMS, 2001, p. 4), attract increasing research attention, largely due to recognition of their economic importance (DCMS, 2001; Howkins, 2002; Hesmondhalgh and Pratt, 2005) and innovative organizational forms (Cohendet and Simon 2007, 2016). Scholars have been interested in a wide variety of creative industries, including advertising (Moeran, 2009), architecture (Jones and Livne-Tarandach, 2008), perfumery (Islam, Endrissat, Noppeney, 2016; Endrissat, Islam, Noppeney, 2015), design (Verganti, 2003), cinema (Cattani et al., 2008; Cattani and Ferriani, 2008), publishing, music, performing arts (Glynn, 2000; Massé and Paris, 2013), haute cuisine (Svejenova, Planellas, and Vives, 2010; Svejenova, Mazza, and Planellas, 2007; Durand, Rao, and Monin, 2007), and video games (Tschang, 2007; Cohendet and Simon, 2007, 2016; Lê, Massé and Paris, 2013; Chiambaretto, Massé and Mirc, 2019).

In addition to this common origin, these distinct industries share structuring economic properties (Caves, 2000), which make creative industries a category that can be considered homogeneous. Caves (2000) underlines six common economic properties of these industries: “nobody knows principle” (uncertainty about success), “art for art’s sake” (intrinsic motivation and creativity), “motley crew” (stratification of jobs, coordination and teamwork), “infinite variety” (competition by originality), “A list/B list” (vertical differentiation, ranking, celebrity tournaments), and “ars longa” (the works are durable or super-durable goods).

Moreover, contrary to the romantic image of the solitary artist they often evoke, the activities in creative industries are collective and involve cooperation (Becker, 1982). This collective dimension (Becker, 1982) combined with the properties highlighted by Caves (2000) leads to the need for organization and processes (Paris, 2017, Paris & Ben Mahmoud-Jouini, 2019), and has a huge impact both on the day-to-day functioning of organizations and on the economics of these fields. Indeed, the opposition between the need for rational processes and the subjective risk-taking mindset intrinsic to creative activities leads to tensions in organizations. Research on creative industries has identified phenomena such as dilemmas or opposing pressures (Lampel, Lant, and Shamsie, 2000), tensions (Tschang, 2007), paradoxes (DeFillippi, Grabher, and Jones, 2007), and opposing logics (Caves, 2000). Within organizations, this opposition is manifested in the tension between artistic and economic logics (Eikhof and Haunschild, 2007). These tensions may act as a polarizing force that pushes an organization towards either a dynamic of differentiation and renewal (Bourdieu, 1993) or a dynamic of rationalization that encourages standard formatting (Tschang, 2007). They push organizations and actors in different directions: creative processes and organizations lead to outputs that are more or less subject to the constraints of formatting and market demands.

An Opposition Between Two Worlds

Creative industries contain opposite “worlds” (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016; Becker, 1982) highlighting the opposition between arts and commerce (Caves, 2000) or between creation and marketing. In each sub-industry, semantic oppositions distinguish the pertinent actors, such as independent versus commercial movies, haute cuisine versus food industry, or haute couture versus fashion industry.

At the industry level, this leads to the emergence of two categories of actors: mainstreamers and mavericks (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016; Becker, 1982). Mainstreamers are well integrated in the professional field, and their work complies with, legitimizes, and reproduces the conventions of an existing art world (Becker, 1976, 1982). According to Patriotta and Hirsch (2016, p. 873), “conformity with conventions provides greater access to resources, makes it easier to produce and distribute their works, and facilitates endorsement of these works by critics and audiences”, which explains why some mainstreamers achieve “superstar” status (Rosen, 1981) in a specific domain and over time.

In contrast, mavericks are “artists who have been part of the conventional art world of their time, place, and medium, but who found it unacceptably constraining, to the point where they were no longer willing to conform to its conventions” (Becker, 1976, p. 703). Because of their unconventional orientation, mavericks are often sources of novelty and innovation in a field (Jones et al., 2016). However, their singularity makes it difficult for them to secure access to resources, support from organizations, or recognition (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016).

At the organizational level, this opposition leads to the emergence of different ways of starting product development processes that employ distinct approaches. Some organizations make little use of market studies and encourage their creative talents to create, while others start with a clear understanding of the subtle dynamics in their markets (market-pull approach). The market-pull approach suggests that innovation starts with an analysis of user needs in specific markets, which sparks a search for technologies, ideas and/or resources that can satisfy these needs. This user-centered approach has prompted the development of substantial research on lead users (Von Hippel, 1986, 1998) as sources of new product development. In the creative industries, for example, Hollywood’s production processes are known for producing movies with precise audience targets, designing them according to strict specifications, and testing early versions with the public (De Vany, 2004; Cattani and Ferriani, 2008; Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016).

In contrast, Verganti (2008, 2009) introduces the notion of “design-driven” innovation and establishes the foundation for this specific perspective, in which design-driven organizations do not implement a user-centered approach (Pisano and Verganti, 2008), nor develop new products through analyses of user needs (Brown, 2009), nor produce incremental innovations (Norman and Verganti, 2014). Companies such as Alessi are not user-centric and make little use of market studies, focus groups, or ethnography (Verganti, 2008; 2009); it is difficult to imagine a user who would ask for a citrus squeezer that looks like a spaceship, as does the Philippe Starck–designed Juicy Salif by Alessi (Verganti, 2003). Therefore, Verganti (2008; 2009) argues that the design-driven approach requires specific types of organizations and processes. Firms that are design-driven differ from firms that are user-driven, in both organizational and process perspectives. In the same vein, Pixar’s production process is described as “creation-oriented”, where marketing functions solely as a tool for selling the product, without transforming it (Catmull, 2008; Paris, 2010).

These two oppositions, design-driven vs. market-driven and mainstreamers vs. mavericks give structure to the creative industries. Insofar as they are based on different points of view, it is unclear whether they may in fact constitute a single opposition. In the rest of the article, we will use the term “worlds” to evoke in a generic way these oppositions in a given creative industry, without referring to one or the other of these points of view.

Collaborations and Crossovers Between Worlds

Some recent studies focus on the existence of links between these worlds, whether by highlighting collaborations between players or by pointing out the shifts that occur in the field (e.g., an artist’s move from one side to the other) (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016). Accordingly, building on Powell and Sandholtz’s (2012) concept of amphibious entrepreneurs, Patriotta and Hirsch (2016) propose the new role of “amphibious artists” who bridge the mainstream and maverick social types. These boundary spanners promote exchanges between mainstreamers and mavericks, and help expand mainstream conventions in new directions (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016).

The amphibious artist’s work contains elements of both novelty and convention, in varying degrees (Alvarez et al., 2005; Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016), which may reduce or resolve the tensions between the opposing logics (Caves, 2000) because artists can reconcile their creativity with social acceptability and are thus able to acquire resources, develop their careers, and achieve recognition. The new conventions developed through a cooperative process that involves amphibious artists also provide a new way to link artists to consumers (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016).

In this perspective, Powell and Sandholtz (2012) argue that innovation and creativity can arise from this approach due to “the creation of new roles, amphibious identities, (and) novel organizational practices” such that “when social relations are transposed from one network to another and mix with the relations already present, raw material is created for invention” (Powell and Sandholtz, 2012, p. 439).

Robert Redford is an example of an innovative amphibious artist (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016) who works in the mainstream and who also founded the Sundance Institute (in 1981), a non-profit organization that aims to “discover, support, and inspire independent film and theatre artists from the United States and around the world, and to introduce audiences to their new work” (Sundance Institute, 2014, cited in Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016, p. 878). Redford thus bridges big budget, star-studded movies from Hollywood and more independent, low budget films featuring less well-known or well-paid actors. For mainstream actors and directors, his efforts nurture creativity by exposing them to alternative sources of inspiration and new ideas at the edges of their social system, while still remaining connected to existing conventions and legitimacy associated with the mainstream (Cattani and Ferriani, 2008; Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016).

Robert Redford’s example also suggests that, in addition to the social role of amphibious entrepreneurs, these collaborations also involve an organizational dimension that sustains different ways of producing and creating. While institutional theory and social network analysis provide some explanations for these collaborations, this organizational dimension has nevertheless been largely ignored by researchers and appears to be a fecund avenue for research.

A Development Process Perspective on the Collaboration Between Worlds

The literature review presented in this section highlights the coexistence of two worlds—a market-oriented focus vs. a design-oriented focus—with different actors and approaches to the product development process. Despite differences in philosophy or approach, some actors operate at the boundaries of these worlds. Scholars mobilize different theoretical perspectives to analyze these oppositions and predict how actors will promote collaboration or crossovers between the worlds. Whereas some emphasize the role of social structures, others are more interested in conventions (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016).

Social network theorists focus on the positions of relevant actors within a core/periphery structure, with the prediction that collaborations between players from different worlds will result from the movement of actors between the periphery and the core of an established network (Becker, 1976, 1982; Cattani and Ferriani, 2008; Sgourev, 2013).

Institutional scholars, on the other hand, emphasize the conventional characteristics of creative production in a specific field, and they anticipate that collaborations between players from different worlds will result from field-level dynamics that produce shifts in conventions over time (Rao, Monin, and Durand, 2005; Lena and Peterson, 2008).

Although the literature has predominantly focused on the role of amphibious actors who bridge the opposing worlds in their social (network) or symbolic (conventional) dimensions, these explanations largely ignore the impact of the processual dimension on these collaborations, which is nevertheless crucial and must be taken into account. Verganti (2008, 2009) gives a first insight by identifying different approaches related to the creative process.

In organizations, process studies “focus attention on how and why things emerge, develop, grow, or terminate over time” and try to “illuminate the role of tensions and contradictions in driving patterns of change, and show how interactions across levels contribute (or not) to change” (Langley et al., 2013, p.1). In this specific perspective, we respond to Patriotta and Hirsch’s (2016, p. 883) call for “in-depth empirical studies of additional art worlds that have experienced significant transformations and followed alternative paths to innovation”.

Our aim in this contribution is thus to add to the literature on collaboration and crossovers in the creative industries by investigating the product development process dimension in the collaboration between worlds. Specifically, we investigate how these collaborations take place in the development process dimension, since they involve actors and institutions with opposite views or philosophies on creation. These collaborations raise another question about the ability of creators to act in two worlds that are based on opposite approaches. This raises issues in terms of personal orientation and in terms of process: how and why are they able to create differently in these worlds, producing very different creations?

Methodological Considerations and Empirical Setting

Since our objective is to describe and understand a new phenomenon (rather than to test propositions), an exploratory research design is appropriate (Miles and Huberman, 2013).

Industry and Case Selection

To address the research question, we focused our attention on the perfume industry, characterized by a bifurcation between two segments that started in the early 2000s (Kubartz, 2011) involving product development process differentiation. The mainstream perfume industry represents the vast majority of the market, and the main players are international groups, such as L’Oréal, LVMH, Procter & Gamble, and Coty. This industry includes manufacturers of flavors, fragrances, and natural or synthetic raw materials. Five companies (IFF, Givaudan, Firmenich, Symrise, and Takasago) represent 60% of the world market (Ellena, 2011). In general, fragrance companies employ several perfume creators (noses), who work alone or with two or three colleagues on perfume creation projects for different brands. But another segment has also developed, with “auteur” perfume companies emerging in the early 2000s, initially in niche positions (e.g., l’Artisan Parfumeur, Serge Lutens). Their perfumes are considered more creative and are marketed through specific distribution channels, some having their own retail network.

In the perfume industry, les Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle (hereafter, EPFM) offers an interesting case, due to its original configuration. Founded in 2000 by Frédéric Malle, a former evaluator in the perfume industry, it maintains a differentiating discourse; that is, the company claims to do things differently to offer “more creative” perfumes. It has its own distribution channel, and it highlights the names of the perfumers, who are promoted as “auteurs”. With this model, the company mobilizes perfume creators who work mainly for mainstream companies. The company has benefited from substantial media exposure and a public reputation for being creative thanks to its work with eminent perfumers. This success led Estée Lauder Companies to buy EPFM in 2014. At the start of this case study, EPFM had existed for eight years and employed approximately 15 people.

Data Collection and Analysis

Inspired by grounded theory and case study methodology (Eisenhardt, 1989; Miles and Huberman, 1994; Strauss and Corbin, 1994), this qualitative case study combines multiple sources of data. Both primary and secondary data were collected to enable the use of triangulation techniques (Eisenhardt, 1989; Gibbert et al., 2008; Lincoln and Guba, 1985). We collected primary data through 19 semi-structured interviews with 16 different persons, some of them working in the mainstream industry, some of them working with EPFM, and two of them being perfumers. All of the interviews were conducted by two researchers and lasted one to two hours each. Interviews with EPFM retail store managers outside France, each conducted by one researcher, lasted approximately 45 minutes. Of these interviews, 11 were recorded and then transcribed as soon as possible to preserve the quality of the data (Gibbert et al., 2008). For the other eight interviews, notes were taken manually during the interview and then transcribed. The interviews focused on the history, responsibilities, and specificities of the company in terms of its creation process, distribution, and customer interactions, as well as differences with other companies. In addition to identifying specific processes within the company, compared with the industry in general, these interviews helped explicate why they were specific. Following Gioia et al. (2013), we assured the interviewees that their names would not be disclosed. Throughout the remainder of this article, the interviewees remain anonymous and are only identified according to their functions within the company or in the sector.

In addition to the interviews, we conducted visits and observation sessions in shops (consultation sessions) and perfume labs in order to gather some details that would help refine our understanding of the process.

Table 1

Table 2

List of interviews

Secondary data were obtained from various sources, including internal documents (e.g., presentations and reports) and external documents (e.g., news articles, books and industry reports). The combination of primary and secondary sources allowed us to triangulate the information by crosschecking facts and dates to avoid potential interpretation biases.

The data analysis approach is intended to be comprehensive (Dumez, 2016). Following the guidelines for inductive research (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Miles and Huberman, 1994), the interviews were analyzed to identify elements that characterize the development of new products in the mainstream industry and in the configuration set up at EPFM. As development processes are intertwined in both a social field and specific organizations, the use of a process perspective requires a multi-level approach (Klein and Kozlowski, 2000). Thus, we consider different levels of analysis (industry, process and creator) that prove to be intertwined in our case.

The data processing was done in two different stages. The first aimed to give us a clear representation of the general processes through which the creation takes place, in both worlds. This stage consisted of an iterative process with data collection, to ensure that the elements obtained during the interviews allowed us to describe the whole creative process in its sequentiality. The aim of the second stage was to understand the interaction between these general processes and the individual creative process. The primary and secondary data were coded according to the recommendations of Miles and Huberman (1994). An abductive method was adopted; the phases of the empirical investigation were alternated with returns to the theoretical literature.

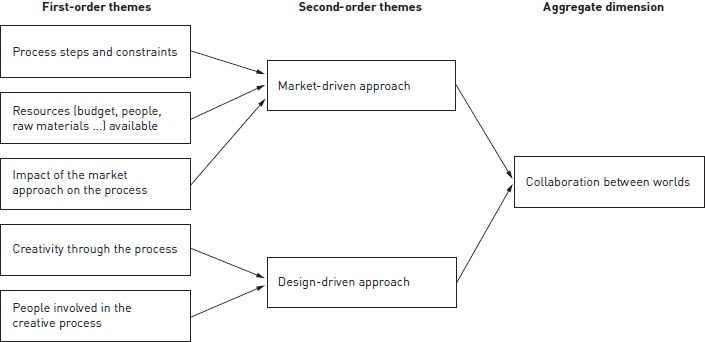

The analytical process comprised two stages. An initial round of coding followed the literature to identify the existence of collaboration between the mainstream perfume industry and EPFM. This round allowed us to ensure that our chosen case and industry were relevant to the study. Then, a more inductive round of coding was undertaken to reveal the role of processes in managing the collaboration between worlds. This second round was inspired by the method proposed by Corley and Gioia (2004) and Gioia et al. (2013). It entailed coding our material in different categories and relative to the creation processes in the mainstream industry and EPFM. We began by identifying first-order categories, which allowed us to label the interviews. We then attempted to arrange the first-order categories within second-order themes to link the first-order categories with the existing literature and identify potential nascent concepts or mismatches. Finally, we attempted to combine the second-order themes into aggregate dimensions to study the relationships between them. An example of the coding is provided in Appendix 1.

Findings: Comparison of Two Product Development Processes With Different Creative Approaches

The results of this research are composed of two parts. The first is a precise description of the entire perfume development process in each of the two worlds, from the initiation of a new perfume project to distribution. The interviews allowed us to reconstitute a precise description of the processes in two configurations: the generic process in the mainstream and the process specific to the EPFM company. The second is the impact of these types of organization and processes on the creators (perfumers) and the creative process.

The Development Process in the Mainstream Industry

A perfume creation process starts with the product manager of the brand’s marketing department, who defines the concept in terms of the perfume’s target group, description, color, and image, determined from market tests, competitor benchmarks, and so on.[3] A product launch date is set early in the process, because at this stage the company also reserves media space for advertising and publicity, along with the desired shelf space at major retailers and distributors. The whole creative process, including creative steps and market testing, as well as alterations, must take place within this time frame. Another major constraint is imposed by the budget, which influences the possible choice of ingredients to use in creating the perfume.

The brand’s product manager launches a competition among different fragrance creation companies by providing them with a brief. The brief usually consists of a story, including a history, images, ambiance, specific environment, films, and even poems. It usually contains standardized terms, such as modern, rich, elegant, mysterious, female, and flowery. The purpose of this story is to define what the perfume’s scent should represent for customers. The various brands send out several hundred briefs annually. Creators must ensure that the fragrance conforms to the established brief and customer target.

The fragrance creation company gives the brief to between one and three of its in-house perfume designers (also called “noses” or “perfumers”). They start to work separately, and when a general note is chosen, the other noses join the one who proposed it to develop the concept.

During the creation of any new perfume, a series of qualitative and quantitative market tests helps determine and assess different elements of the future product, which can reduce the risk involved in a new product launch. In market tests, the firm evaluates various parameters that define perfume quality, such as how long the perfume scent remains in the room and how long the perfume is active on the skin. If these parameters are not satisfactory, the perfume may be abandoned. If satisfactory, the perfume is tested in major markets in blind tests with representative consumer panels that match the target market. Depending on the result, the noses may need to rework the fragrance. The next phase of market testing consists of the “sniff and use” test: A group of customers tests and evaluates the perfume over a longer period, generally one month.

Finally, the full mix test takes place a few months before product launch. This test assesses the coherence of the fragrances, the packaging, and the advertising messages. Even at this stage, two or three options may still remain for the final fragrance, to reduce product launch risk further. On attaining satisfactory results in these different test phases, the selected perfume is launched on different markets, along with vast media coverage and special product launch promotions in the major distribution channels.

The creation and distribution of perfumes are similar to the creation and distribution of fast-moving consumer goods, aimed at attracting customers with brand image, advertising, and visual elements (e.g., packaging, bottle). The brands invest heavily in global advertising campaigns, especially for product launches. The increased number and high costs of product launches and short product life cycles mean that brands have to make a significant amount of sales shortly after product launch to achieve a rapid return on their investment. Customers spend a short time in self-service perfume stores, with virtually no qualified sales people, so perfumes have to offer a scent that immediately pleases a substantial number of customers. Retailers get incentives to sell the latest releases, so the perfume brand can earn back its promotional budget through rapid, massive sales.

The Development Process at EPFM

The development process at EPFM is much simpler and involves fewer people. The initiator of the process is either Frédéric Malle or one of the perfumers with whom he works and with whom he maintains an ongoing conversation. These perfumers are leading noses working for the major fragrance creation companies and creating perfumes for the most prestigious brands. One of them may suggest an idea and then work on this idea at his or her own pace. At EPFM, these perfumers do not have any conventional constraints; they can use any raw material they wish to create the perfume. They enjoy substantial freedom in terms of timing (no deadlines) and ingredient costs (no limits on costs or selling prices). Their names feature prominently on the bottles of the perfumes they create, but they are not paid for the work. Instead, they agree to create perfumes for EPFM because they are given the opportunity to create without any constraints.

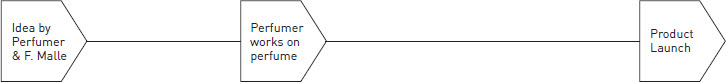

figure 1

The development process in the mainstream industry

The development time frame does not allow creators enough time to mature their projects. As a result, several perfumers are called in to work on each project, making them less personal. Another consequence is that perfumers reuse ideas developed in the past for other briefs. Budget constraints are defined by the briefs: they drastically limit the choice of raw materials.

The brief should influence the creation of the perfume. Its presentation is more about the target and an atmosphere (which will be found in the advertising), and does not give useful directions for perfume creation. This means that the perfume teams can reuse old ideas and projects.

The different kinds of consumer tests impact the creation process. For example, the Blind Tests dictate that fragrances must immediately appeal to consumers who smell them. There is pressure on perfumers to integrate whatever satisfies or appeals to the consumers if their proposal is to have any chance of winning. This pushes them to make perfumes that do not diverge too much from what already exists on the market.

Sales take place in distribution systems that employ low-skilled salespeople, who receive incentives for selling brand-driven fragrances. The customer’s decision is therefore influenced more by advertising than by salespeople. The perfumes must be immediately familiar to customers who come into the shop to smell them. This limits the ability of creators to offer fragrances that go off the beaten track.

figure 2

The development process at EPFM

Frédéric Malle likens his company to a “publishing house” for noses, in the sense that he publishes perfumes designed by “auteurs” according to their own desire for expression. Perfume designers are afforded total freedom in terms of budget and development time. There is no market research or testing.

EPFM does not target any specific customer group and proposes atypical scents, launched depending on the opportunities identified and chosen jointly by the nose and Frédéric Malle. The objective is to allow customers to find the “perfume of their life,” which will remain available, even if sold only in low numbers. EPFM does not engage in market testing during the development process; only the nose and Frédéric Malle test and evaluate the product during this process and eventually decide whether to launch the perfume.

EPFM eschews the use of advertising, which might not match the timing of new perfume releases. Distribution is done through EPFM’s own stores or a network of exclusive partners in different countries—mostly renowned, independent perfume stores. In 2017, EPFM had eight company-owned stores in Europe and the United States, as well as a network of selected partner stores in 43 countries that sell the perfumes under a distribution agreement. Sales assistants in the stores play the primary role: They receive intensive training on fragrances in general and on the most prominent perfumes on the market. They welcome customers for in-store consultations, inquire about their tastes and preferences, and suggest they try a maximum of three perfumes.

In some stores, special glass columns provide an ideal olfactory experience. Sales assistants also encourage customers to try the fragrances at home, providing them with samples and inviting them to come back after they have had the chance to experience the scent, without pushing them into an immediate purchase. Having a rich background and personality, these sales assistants assume a true advisory role.

Table 3

Development processes in the mainstream industry and at EPFM

Two Opposite Worlds and two Different Contexts for Creation

First of all, these results highlight radical differences between the development processes in the two generic worlds of the perfume industry: the market-driven one represented by the mainstream industry and the design-driven one represented by EPFM.

The process (...). How things happen from the moment we get a request from a customer. In fact, there are two major types of projects. We have projects that target large groups — L’Oreal, Procter, Clarins, Coty... [...] Now there is another type of development, the so-called perfumes for niche markets.

Perfumer 1

The differentiation in positioning—market-driven or design-driven—echoes radical differences in the development process, from its very initiation to distribution. In particular, this differentiation shows that the marketing approach is very different in the two processes. In the mainstream industry, marketing has an important influence on the creative process, whereas at EPFM, it is very limited and does not explicitly intervene until after the creation of the perfume, consistent with the practice in cultural and creative industries (Colbert, 2003).

This empirical observation confirms the cohabitation of opposing worlds, as suggested in the literature (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016; Caves, 2000; Becker, 1982), showing that this segmentation is rooted in differentiated development processes.

Secondly, these results also concern creators operating in such different worlds. At first glance, it would seem appropriate that these creators should differ depending on which world they operate in. However, the same perfumers work in both worlds in the perfume industry. How is it that they are able to create differently in worlds that are based on different approaches, and produce such very different creations?

The apparent ability of creators to radically change their creative approach may be explained by the product development process in which they are working.

I can do things with Frédéric Malle that I couldn’t do elsewhere, due to prices and to the fact that I am dealing with a single person.

Perfumer 1

For mainstream companies, such a collaboration with the other world may be a way of alleviating any frustration that their creators may experience in their day-to-day creative activity, as it offers them an unrestrained outlet for their creativity. These companies also benefit from the market visibility generated by these collaborations.

As we have had a lot of coverage in the press and today the big brands are run by product managers who are not very familiar with the job, but are obsessed with media criticism, it is very important for a perfumer to be spotlighted. Today, we are the brand that values them the most, so we are a way for laboratories to shine a light on their creators.

F. Malle

Understanding how a creator can move from one world to the other, as far as creative products (positioning, approach, etc.) are concerned, is a key goal of this research. We find that creativity, defined as the ability to deliver such-and-such a product, is determined by the development process in which creators work. Incorporating them into a different process will alter the way they create.

Third, the development process can restrict the ability of perfumers to express their creative potential. This limitation is due to the process, and more precisely to a general systemic context in which development processes, distribution, promotion and the general configuration of the industry are intertwined.

The market is segmented by customer type, and products are adapted to specific segments. While this approach can be described as innovative, it is not creative. These products are predesigned to match a specific, targeted consumer profile. The result of this vision of the market is that the brands design products that will please everyone. Choices are guided by tools designed to identify demand and consumer tastes: perfume classification, analysis of international markets, trend books… focus groups, and above all, market testing.

Perfumer 2

Indeed, several mechanisms in the market and the distribution system constrain creativity and firms adjust their creative process to match the spaces available in the distribution system. Self-service distribution demands self-explanatory, fast-moving perfumes that can be promoted through advertising campaigns and without personalized assistance from a well-trained sales person. Product promotion through costly advertising campaigns must generate sales to provide a rapid return on investment before the next perfume can be launched. As the frequency of product launches accelerates, a vicious circle arises that increasingly prevents the sale of creative, atypical fragrances. The mainstream industry’s dominant operating mode and its creative process constrain creativity and limit the ability to release certain perfumes. This general process has some influence on the creative part of it. The noses often adjust existing fragrances only slightly, to differentiate them just minimally, which is a consequence of having customers in test phases, since they generally prefer scents they already know. In addition, the logic of competition dictates that noses work on many projects that will never be accepted. Recognizing their time constraints, they turn to already-created projects that had not been green-lighted for development, regardless of the original brief or its source.

Thus, the differences between brands become blurred. Finally, the briefs are designed by marketing managers, who think primarily about customer targets, so hundreds of these briefs are highly similar, which is not conducive to creativity.

Discussion: Polarization, Multi-Level Analysis and Creative Symbiosis

This research aims to contribute to the creative industry field, which is currently being structured. The literature on creative industries highlights the coexistence of opposite worlds in some industries, structured around different companies, different individuals and different approaches to product creation. Researchers have highlighted bridges between these two worlds, mainly from a social structure point of view, but have not considered these crossovers in relation to the product development process. This paper focuses on how and why talents are able to cross from one world to another and create differently in these worlds based on different creative approaches, giving rise to very different creations. It also enriches our understanding of these polarization phenomena in creative industries.

Table 4

Contexts for creation in the mainstream industry and at EPFM

A Polarization Rooted in the General Organization of the Industry

This research enriches our understanding of these two worlds and highlights a real polarization between them in the perfume industry. In the context of creative industries, we define polarization as an opposition between coexistent worlds, which is rooted in their very processes and consequently in all the components of the industry. These worlds bring different actors into play, different processes, different creations, all these elements being closely interconnected.

Verganti (2009) offers a first insight into this polarization of worlds by showing differences in organizational approaches in relation to the development process. Some organizations develop new creative products with a market-driven approach, while others follow a design-driven approach. Referring to this distinction, the functioning of the mainstream segment of the perfume industry is market-driven, while EPFM is design-driven.

The results of this research allow us to take this idea further. The two worlds rest on different ways of doing things and different industrial structures. Shaping the way a world functions, these different dimensions give rise to worlds that are opposite in every aspect, including creation processes, promotion, and distribution. This polarization is not only a question of individuals and social networks or of development processes, but rather is a systemic phenomenon. Market-pull and design-driven orientations are not based on an individual approach to creation; they are deeply rooted in the processes and general organization of the industry. Compared to previous research on collaboration between worlds, this study provides a denser perspective, showing individuals embedded in structured contexts. To take this process dimension into account, in addition to the social dimension usually put forward, we propose to consider that these worlds are two poles of a creative industry.

The Multi-Level Impact of Context on Creation

This research also enriches our understanding of creative processes, since it shows that multiple levels of analysis are intertwined (industry, process and creator). Research on the creative industries focuses either on the institutional or field dimension (Cattani and Ferriani, 2008; Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016) or on the organizational or process dimension (Verganti, 2008; 2009). These different levels of analysis need to be considered together in order to gain a more complete understanding of the creative process. Perfumers are not just individuals with a certain creative capability. Their creative capability depends on the process in which they are involved and the general industry context. Consistent with Becker’s view (1982), creative processes are a complete chain that starts with the individual creation process and continues until the distribution of the products on the marketplace.

This holistic view is conducive for example to understanding how one individual working in two different worlds can produce very different creations. It is necessary to have a global view of the creative process that recognizes creation as the result of the individual or collective creative process, embedded in a formal process and in a structured industry context.

Beyond Amphibious Artists, Creative Symbiosis as a Specific Collaboration Configuration

The literature on collaborations between worlds in the creative industries focuses on the social (Cattani and Ferriani, 2008; Sgourev, 2013) or symbolic dimensions (Rao, Monin, and Durand, 2005; Lena and Peterson, 2008). These studies suggest that these two worlds are not sealed off. Bridges between them exist and this explains the renewal of one world by the creativity of the other. Passages between worlds are opened by intermediary actors. These can either be amphibious actors, who leverage their recognition/standing in the mainstream world to invite independent artists to enter (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016), or an intermediate ecosystem, the “middleground”, that sustains the circulation of ideas from the “underground” to the “upperground” (Cohendet, Grandadam and Simon; 2010). These bridges are responsible for the creative dynamic in these worlds. The extant literature focuses on the conventional dimension as the main barrier to the circulation of new ideas or new talents.

The EPFM case provides ample material to discuss and enrich this perspective. Collaborations may hinge on amphibious artists whose role is to introduce mavericks into the mainstream social networks (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016). Frédéric Malle, a former player in a mainstream company, and the perfumers are perfectly conversant with mainstream conventions and are integrated in its social networks. Furthermore, the market segment represented by EPFM is not associated by insiders with unconventional creation. In contrast, to take an example from the art world, the work of impressionist painters was not recognized at first by mainstream institutions (Wijnberg and Gemser, 2000). In the perfume industry, “auteur” perfumery is well recognized by mainstream actors. The situation described in our study is a new configuration of collaboration between two worlds in a creative industry. These kinds of collaborations can be explained by arguments about development processes and the creative capability they offer. Creators can create in very different ways depending on the context in which they are embedded. Through such collaborations, designers from the market-driven pole find a space and opportunities for “auteur” creation that they cannot find in their usual context. Their ability to create in some way (design-driven or market-driven) is due to their embeddedness in one general process or another. This explains how designers can change their creative orientation when moving from one world to the other. Mainstream companies are rekindling their interest in these collaborations as they benefit from the media coverage of their creators.

This introduces a new important dimension. Whereas the explanations in terms of a “middleground” (Cohendet, Grandadam and Simon; 2010) or amphibious artists (Patriotta and Hirsch, 2016) suggest that both worlds are structured by different social networks and conventions, this research highlights the importance of the global context and process dimension. It also suggests that idea circulation might not be the main issue. The capacity of the general context and process to accept or sustain original ideas is a bigger issue than their generation.

Since they have no difficulty entering one world or the other, from a legitimacy or social network point of view, one may ask why these creators do not simply choose one of the two worlds. This research provides some answers to this issue. First, due to its hegemony, the mainstream market-driven pole can attract the most creative designers, offering them resources, wages, and access to the mass market. When they work with the other pole, they find themselves in another context that allows them a much wider range of expression.

Second, the collaboration between the two worlds takes place in an equilibrium. This configuration constitutes a novel form that we propose to call “creative symbiosis”. In biology, symbiosis refers to the “interaction between two organisms living in close physical proximity, typically to the advantage of both” (Oxford English Dictionary). We define “creative symbiosis” as a collaboration of creators from the market-driven pole of a creative industry with the design-driven pole. In our study, this collaboration takes the form of a crossover where creators who usually operate in one world momentarily cross into the other world to develop a particular project. The world consists of the different components of the sector: the industrial organization, the distribution and promotion system, and the pace of product development form a constraining framework around creation. For creators, working in a different world changes the available resources and constraints, in particular allowing them to work in a less constrained environment.

Conclusion

This paper focuses on the product development process in collaborations between opposite worlds in creative industries. A literature review has shown that these collaborations between worlds are still misunderstood, mainly concerning the ability of creators to move from one world to another with an opposite creative approach. Much has been said about the existence of social structures and conventions in creative industries, but little about the product development process perspective on collaborations between worlds. This article provides an initial and exploratory step in that direction.

The contributions of this research are threefold. First, it enriches our understanding of the coexistence of different worlds in creative industries, by introducing a process perspective. Through this perspective we identify the deep structures of the differentiation between the opposing worlds: it is not only a question of different conventions, but also of all the components of each world (industry organization, creation process, system of distribution and promotion, etc.) that frame the creation.

Second, it highlights the weight of the industrial environment on the creative capability of an individual actor. Given these conditions, the different creative capabilities of a creative industry’s different worlds cannot be perceived only in terms of individual or organizational creativity. An individual or organization may well have creative potential, but their industry might be unable to support their proposals.

Third, we have highlighted a particular form of collaboration in which a creator from one world momentarily works with the opposite world. This collaboration entails different resources and constraints, which allows creators, in our example, to enjoy creative freedom. We call this new bridging configuration “creative symbiosis”.

From a practical point of view, these results offer a better understanding of the structural limitations on creative capacity in a given context. They also make it possible for actors to see the liberating potential of creative symbiosis in the face of industries that are resistant to creativity.

The main limitation of this work is the general limitation that applies to all case studies. This research reveals the existence of a novel configuration but cannot confirm the extent to which such a configuration exists in other situations. Further research might examine other potentially similar situations, such as the movie industry, where directors work for Hollywood and also on more personal or independent films. An interesting question to ask is whether the paradoxical situation of the mainstream perfume industry, which seems to impede the launch of innovative perfumes, appears in other creative industries too. Other situations might also be compared with this case, even beyond the creative industries. In entrepreneurship, the success of third places (e.g., co-working spaces, fab labs, hacker spaces), the interest they have raised among big companies, and the collaboration they seemingly encourage might be studied in relation to the analytical framework proposed in this study.

Appendices

Appendix

appendix 1. Example of the coding

Biographical notes

Thomas Paris is a researcher at CNRS (GREGHEC) and an affiliate professor at HEC Paris. PhD in management, he specialized in the economy of creation and creative industries. He studies these sectors (cinema and audiovisual, music, fashion, publishing, architecture, advertising, haute cuisine, design...) from the managerial, organizational and sectoral viewpoints, in collaboration with their actors. His research also focuses on innovation management, entrepreneurship, the digital economy and cultural policies. At HEC, he is the director of the MSc. MAC (Media, Art, Creation).

Gerald Lang is Professor at KEDGE Business School since 2008. Prior to this, he held various positions as Strategy and Development Director and Project Director within different international companies (Bertelsmann Group, Kering Group…) responsible for international operational improvement as well as strategic repositioning. He obtained his doctorate from Ecole polytechnique in Paris. His teaching and research interests are in Supply Chain Management, Strategic evolutions in the retail sector and Intercultural Management.

David Massé is an Associate professor in management, head of the economics and management group at Télécom ParisTech and a researcher at the Interdisciplinary Institute of Innovation (i3-SES). He is a doctor from École polytechnique and worked for five years as a researcher at Ubisoft’s Strategic Innovation Lab. His work focuses on the organization of the creative industries, the impact of digital technology on innovation processes and the various business models of the sharing economy.

Notes

-

[1]

These perfumers are the ones who have developed at least two perfumes for EPFM.

-

[2]

The perfumers have often worked for different companies during their career.

-

[3]

A variation mode has developed in recent years in multi-brand companies: perfumers can propose ideas for perfumes based on an association of two fragrances (e.g., “greedy iris”). Ideas that are considered interesting by the company are then worked on and tested through all development stages. If they get excellent results in all the market tests, they are “put on a shelf” and are likely to be chosen to respond to a brief from one of the brands in the company’s portfolio.

Bibliography

- Abernathy, William J.; Utterback, James M. (1978). “Patterns of Industrial Innovation,” Technology Review, Vol. 64, N° 7, p. 254-228.

- Alvarez, José Luis; Mazza, Carmelo; Strandgaard Pedersen, Jesper; Svejenova, Silviya (2005). “Shielding Idiosyncrasy from Isomorphic Pressures: Towards Optimal Distinctiveness in European Filmmaking,” Organization, Vol. 12, N° 6, p. 863-888.

- Becker, Howard S. (1976). “Art Worlds and Social Types,” American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 19, N° 6, p. 703-718.

- Becker, Howard S. (1982). Art Worlds, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1993). The Field of Cultural Production, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Brown, Tim (2009). Change by Design, New York: HarperCollins, Harper Business.

- Catmull, Edwin (2008). “How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 86, N° 9, p. 64-72.

- Cattani, Gino; Ferriani, Simone (2008). “A Core/Periphery Perspective on Individual Creative Performance: Social Networks and Cinematic Achievements in the Hollywood Film Industry,” Organization Science, Vol. 19, N° 6, p. 824-844.

- Cattani, Gino; Ferriani, Simone; Negro, Giacomo; Perretti, Fabrizio (2008). “The Structure of Consensus: Network Ties, Legitimation, and Exit Rates of U.S. Feature Film Producer Organizations,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 53, N° 1, p. 145-182.

- Caves, Richard E. (2000). Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Chiambaretto, Paul; Massé David, Mirc Nicola (2019). ““All for One and One for All?”-Knowledge broker roles in managing tensions of internal coopetition: The Ubisoft case.” Research Policy, Vol. 48, N° 3, p. 584-600.

- Cohendet, Patrick; Grandadam, David; Simon, Laurent (2010). “The anatomy of the creative city,” Industry and innovation Vol. 17, N° 1, p. 91-111.

- Cohendet, Patrick; Simon, Laurent. (2007). “Playing across the playground: paradoxes of knowledge creation in the videogame firm,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 28, N° 5, p. 587-605.

- Cohendet, Patrick; Simon, Laurent (2016). “Always Playable: Recombining Routines for Creative Efficiency at Ubisoft Montreal’s Video Game Studio,” Organization Science, Vol. 27, N° 3, p. 614-632.

- Colbert, François (2003). “Entrepreneurship and Leadership in Marketing the Arts,” International Journal of Arts Management, Vol. 6, N° 1, p. 30-39

- DCMS (2001). Creative Industries Mapping Document. UK Government Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

- De Ferrière le Vayer, Marc (2007). “Des Métiers D’art À L’industrie Du Luxe En France Ou La Victoire Du Marketing Sur La Création,” Entreprises et Histoire, Vol. 46, N° 1, p. 157-176.

- De Vany, Arthur (2004). Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes the Film Industry. London: Routledge.

- DeFillippi, Robert; Grabher, Gernot; Jones, Candace (2007). “Introduction to Paradoxes of Creativity: Managerial and Organizational Challenges in the Cultural Economy,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 28, N° 5, p. 511-521.

- Dell’Era, Claudio; Verganti, Roberto (2010). “Collaborative Strategies in Design-Intensive Industries: Knowledge Diversity and Innovation,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, N° 1, p. 123-141.

- Dorado, Silvia (2005). “Institutional Entrepreneurship, Partaking, and Convening,” Organization Studies, Vol. 26, N° 3, p. 385-414.

- Dumez, Herve (2016). Comprehensive research: A methodological and epistemological introduction to qualitative research, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Durand, Rodolphe; Rao, Hayagreeva; Monin, Philippe (2007). “Code and Conduct in French Cuisine: Impact of Code Changes on External Evaluations,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 28, N° 5, p. 455-472.

- Eikhof, Doris Ruth; Haunschild, Axel (2007). “For Art’s Sake! Artistic and Economic Logics in Creative Production,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 28, N° 5, p. 523-538.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. (1989). “Building Theories from Case Study Research,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, N° 4, p. 532-550.

- Ellena, Jean-Claude (2011). Perfume: The Alchemy of Scent. eBook edition. Arcade Publishing.

- Endrissat, Nada; Islam, Gazi; Noppeney, Claus (2016). “Visual organizing: Balancing coordination and creative freedom via mood boards,” Journal of Business Research Vol. 69, N° 7, p. 2353-2362.

- Gioia, Dennis A.; Corley, Kevin G.; Hamilton, Aimee L. (2013). “Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology,” Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 16, N° 1, p. 15-31.

- Geels, Frank W. (2004). “From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-Technical Systems: Insights about Dynamics and Change from Sociology and Institutional Theory,” Research Policy, Vol. 33, N° 6, p. 897-920.

- Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W. (2010). “The ‘what’ and ‘how’ of Case Study Rigor: Three Strategies Based on Published Research,” Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 13, N° 4, p. 710-737.

- Glaser, Barney G.; Strauss, Anselm L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.

- Glynn, Mary Ann. (2000). “When Cymbals Become Symbols: Conflict Over Organizational Identity Within a Symphony Orchestra.” Organization Science, Vol. 11, N° 3, p. 285-298.

- Gomez, Marie-Léandre; Bouty, Isabelle (2011). “The Emergence of an Influential Practice: Food for Thought,” Organization Studies, Vol. 32, N° 7, p. 921-940.

- Hesmondhalgh, David; Pratt, Andy C. (2005). “Cultural Industries and Cultural Policy,” International Journal of Cultural Policy, Vol. 11, N° 1, p. 1-13.

- Howkins, John (2002). The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas, London: Penguin Global.

- Islam, Gazi; Endrissat, Nada; Noppeney, Claus (2016). “Beyond ‘the Eye’ of the Beholder: Scent Innovation through Analogical Reconfiguration,” Organization Studies Vol. 37, N° 6 (June), p. 769-95. doi: 10.1177/0170840615622064.

- Jones, Candace; Livne‐Tarandach, Reut (2008). “Designing a Frame: Rhetorical Strategies of Architects,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 29, N° 8, p. 1075-1099.

- Jones, Candace; Svejenova, Silviya; Strandgaard Pedersen, Jesper; Townley, Barbara (2016). “Misfits, Mavericks and Mainstreams: Drivers of Innovation in the Creative Industries,” Organization Studies, Vol. 37, N° 6, p. 751-768.

- Klein, Katherine J.; Steve W. J. “From Micro to Meso: Critical Steps in Conceptualizing and Conducting Multilevel Research,” Organizational Research Methods Vol. 3, N° 3 (July 2000), p. 211-36. doi: 10.1177/109442810033001.

- Krippendorff, Klaus (1989). “On the Essential Contexts of Artifacts or on the Proposition That ‘Design Is Making Sense (Of Things)’,” Design Issues, Vol. 5, N° 2, p. 9-39.

- Kubartz, Bodo (2011). “Sensing Brands, Branding Scents: On Perfume Creation in the Fragrance Industry,” in Andy Pike (Ed), Brands and Branding Geographies, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., p. 125-149.

- Lampel, Joseph; Lant, Theresa; Shamsie, Jamal (2000). “Balancing Act: Learning from Organizing Practices in Cultural Industries,” Organization Science, Vol. 11, N° 3, p. 263-269.

- Langley, Ann; Smallman, Clive; Tsoukas, Haridimos; Van de Ven, Andrew H. (2013). “Process Studies of Change in Organization and Management: Unveiling Temporality, Activity, and Flow,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 56, N° 1, p. 1-13.

- Lê, Patrick L.; Massé, David; Paris, Thomas (2013). “Technological Change at the Heart of the Creative Process: Insights From the Videogame Industry,” International Journal of Arts Management, Vol. 15, N° 2, p 45-59.

- Lena, Jennifer C.; Peterson, Richard A. (2008). “Classification as Culture: Types and Trajectories of Music Genres,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 73, N° 5, p. 697-718.

- Massé, David; Paris, Thomas (2013). “Former pour entretenir et développer la créativité de l’entreprise: les leçons du Cirque du Soleil,” Gestion, Vol. 38, N° 3, p. 6-15.

- Miles, Matthew B.; Huberman, A. Michael (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, Newcastle: Sage.

- Moeran, Brian (2009). “The Organization of Creativity in Japanese Advertising Production,” Human Relations, Vol. 62, N° 7, p. 963-985.

- Norman, D. A.; Verganti, R. (2014). “Incremental and Radical Innovation: Design Research vs. Technology and Meaning Change,” Design issues, Vol. 30, N° 1, p. 78-96.

- Paris, Thomas (2010). Manager la créativité: Innover en s’inspirant de Pixar, Ducasse, les Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Hermès..., Paris: PearsonVillage Mondial.

- Paris, Thomas (2017). “Exploring the specificities of new product development in creative industries,” 24th Innovation and Product Development Management Conference, Reykjavik, Iceland, 11-13 June 2017.

- Patriotta, Gerardo; Hirsch, Paul M. (2016). “Mainstreaming Innovation in Art Worlds: Cooperative Links, Conventions and Amphibious Artists,” Organization Studies, Vol. 37, N° 6, p. 867-887.

- Pisano, Gary P.; Verganti, Roberto (2008). “Which Kind of Collaboration Is Right for You?” Harvard Business Review, Dec. 2008.

- Powell, Walter W.; Sandholtz, Kurt W. (2012). “Amphibious Entrepreneurs and the Emergence of Organizational Forms,” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Vol. 6, N° 2, p. 94-115.

- Rao, Hayagreeva; Monin, Philippe; Durand, Rodolphe (2003). “Institutional Change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle Cuisine as an Identity Movement in French Gastronomy,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 108, N° 4, p. 795-843.

- Rao, Hayagreeva; Monin, Philippe; Durand, Rodolphe (2005). “Border Crossing: Bricolage and the Erosion of Categorical Boundaries in French Gastronomy,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 70, N° 6, p. 968-991.

- Rosen, Sherwin (1981). “The Economics of Superstars,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 71, N° 5, p. 845-858.

- Sgourev, Stoyan V. (2013). “How Paris Gave Rise to Cubism (and Picasso): Ambiguity and Fragmentation in Radical Innovation,” Organization Science, Vol. 24, N° 6, p. 1601-1617.

- Strauss, Anselm; Corbin, Juliet (1994). “Grounded Theory Methodology,” Handbook of Qualitative Research, London, Thousand Oaks: Sage, p. 273-285.

- Svejenova, Silviya; Mazza, Carmelo; Planellas, Marcel (2007). “Cooking up Change in Haute Cuisine: Ferran Adrià as an Institutional Entrepreneur,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 28, N° 5, p. 539-561.

- Svejenova, Silviya; Planellas, Marcel; Vives, Luis (2010). “An Individual Business Model in the Making: A Chef’s Quest for Creative Freedom,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, N° 2-3, p. 408-430.

- Tschang, F.T. (2007). “Balancing the Tensions Between Rationalization and Creativity in the Video Games Industry,” Organization Science, Vol. 18, N° 6, p. 989-1005.

- Verganti, Roberto (2003). “Design as Brokering of Languages: Innovation Strategies in Italian Firms,” Design Management Journal, Vol. 14, N° 3, p. 34-42.

- Verganti, Roberto (2008). “Design, Meanings, and Radical Innovation: A Metamodel and a Research Agenda,” Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 25, N° 5, p. 436-456.

- Verganti, Roberto (2009). Design-Driven Innovation, Cambridge: Harvard Business Press.

- Von Hippel, Eric (1986). “Lead Users: A Source of Novel Product Concepts,” Management Science, Vol. 32, N° 7, p. 791-805.

- Von Hippel, Eric (1998). “Economics of Product Development by Users: The Impact of ‘Sticky’ Local Information,” Management Science, Vol. 44, N° 5, p. 629-644.

- Wijnberg, Nachoem M.; Gemser, Gerda (2000). “Adding Value to Innovation: Impressionism and the Transformation of the Selection System in Visual Arts,” Organization Science, Vol. 11, N° 3, p. 323-329.

- Yin, Robert K. (2012). Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Thomas Paris est chercheur au CNRS (GREGHEC) et professeur affilié à HEC Paris. Docteur en gestion, il s’est spécialisé sur l’économie de la création et des industries créatives. Il étudie ces secteurs (cinéma et audiovisuel, musique, mode, édition, architecture, publicité, grande cuisine, design...) sous les angles managérial, organisationnel et sectoriel, en collaboration avec leurs acteurs. Il travaille par ailleurs sur le management de l’innovation, l’entrepreneuriat, l’économie numérique et les politiques culturelles. À HEC, il dirige le MSc. MAC (Médias, Art, Création).

Gerald Lang est professeur à KEDGE Business School depuis 2008. Avant, il a exercé des responsabilités opérationnelles en tant que Directeur Stratégie et Développement et Directeur de Projets dans différents groupes français et allemand (Bertelsmann, Kering...). Il était notamment en charge des améliorations opérationnelles au niveau international ainsi que des repositionnements stratégiques. Il a obtenu son doctorat à l’Ecole polytechnique Paris. Ses activités de recherche et de l’enseignement portent essentiellement sur le Supply Chain Management, les évolutions stratégiques dans le secteur de la distribution, et le management international et interculturel.

David Massé est maître de conférences, responsable du groupe économie-gestion à Télécom ParisTech et chercheur à l’institut interdisciplinaire de l’innovation (i3-SES). Il est docteur de l’École Polytechnique et a travaillé pendant cinq ans comme chercheur au Strategic Innovation Lab d’Ubisoft. Ses travaux portent sur l’organisation des industries de la création, l’impact du numérique sur les processus d’innovation et les différents business models et logiques d’action de l’économie collaborative.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Thomas Paris es investigador del CNRS (GREGHEC) y profesor afiliado de HEC Paris. Doctor en gestión, especializado en economía de la creación e industrias creativas. Estudia estos sectores (cine y audiovisual, música, moda, publicaciones, arquitectura, publicidad, alta cocina, diseño...) desde el punto de vista empresarial, organizativo y sectorial, en colaboración con sus actores. También trabaja en la gestión de la innovación, el espíritu empresarial, la economía digital y las políticas culturales. En HEC, dirige el MSc. MAC (Medios, Arte, Creación).

Gerald Lang es profesor en KEDGE Business School desde 2008. Anteriormente, ocupó diversos cargos como Director de Estrategia y Desarrollo y Director de Proyectos en diferentes compañías internacionales (Grupo Bertelsmann, Grupo Kering...) responsable de la mejora operativa internacional y reposicionamiento estratégico. Obtuvo su doctorado en Ecole polytechnique de París. Sus intereses en docencia e investigación son la gestión de la cadena de suministro (Supply Chain Management), la evolución estratégica en el sector minorista y la gestión intercultural.

David Massé es profesor asociado de gestión, responsable del grupo de economía y gestión de Télécom ParisTech e investigador del Instituto Interdisciplinario de Innovación (i3-SES). Es doctor en administración de École polytechnique y trabajó durante cinco años como investigador en el Laboratorio de Innovación Estratégica de Ubisoft. Su trabajo se centra en la organización de las industrias creativas, el impacto de la tecnología digital en los procesos de innovación y los diversos modelos de negocios de la economía del intercambio.

List of figures

figure 1

The development process in the mainstream industry

The development time frame does not allow creators enough time to mature their projects. As a result, several perfumers are called in to work on each project, making them less personal. Another consequence is that perfumers reuse ideas developed in the past for other briefs. Budget constraints are defined by the briefs: they drastically limit the choice of raw materials.

The brief should influence the creation of the perfume. Its presentation is more about the target and an atmosphere (which will be found in the advertising), and does not give useful directions for perfume creation. This means that the perfume teams can reuse old ideas and projects.

The different kinds of consumer tests impact the creation process. For example, the Blind Tests dictate that fragrances must immediately appeal to consumers who smell them. There is pressure on perfumers to integrate whatever satisfies or appeals to the consumers if their proposal is to have any chance of winning. This pushes them to make perfumes that do not diverge too much from what already exists on the market.

Sales take place in distribution systems that employ low-skilled salespeople, who receive incentives for selling brand-driven fragrances. The customer’s decision is therefore influenced more by advertising than by salespeople. The perfumes must be immediately familiar to customers who come into the shop to smell them. This limits the ability of creators to offer fragrances that go off the beaten track.

figure 2

The development process at EPFM

List of tables

Table 1

Table 2

List of interviews

Table 3

Development processes in the mainstream industry and at EPFM

Table 4

Contexts for creation in the mainstream industry and at EPFM