Abstracts

Abstract

This article studies mediated stance in the transedited news headlines on the 2018 China-U.S. trade conflict. It draws on Appraisal theory developed by Martin and White (2005) to examine the transeditor’s stance via an analysis of 66 English news headlines and 50 Chinese headlines. The English texts were collected from the American mainstream media, while the Chinese texts were chosen from China’s major presses. The result of the analysis shows that when news headlines are transedited from English to Chinese, stance mediation normally sounds negative towards the U.S. and positive towards China. The investigations also found that the selected Chinese presses predominantly showed heteroglossic patterns in the mediated stance they took while the English media tended to use monoglossic ones. It is argued that possible reasons for such stance deviation may include ideological tendencies of the media, different readerships and their expectations of the American and Chinese media, and the different socio-cultural beliefs between the two countries.

Keywords:

- appraisal,

- trade conflict,

- news headlines,

- transediting,

- stance meditation

Résumé

Cet article étudie la position de médiation dans les gros titres de l’actualité sur le conflit commercial sino-américain de 2018. Il s’appuie sur la théorie de l’évaluation développée par Martin et White (2005) pour examiner la position du transéditeur à travers une analyse de 66 titres de nouvelles anglaises et 50 titres chinois. Les textes anglais ont été recueillis auprès des principaux médias américains, tandis que les textes chinois ont été choisis parmi les principales presses chinoises. Le résultat de l’analyse montre que lorsque les gros titres des nouvelles sont transférés de l’anglais vers le chinois, la médiation de position semble normalement négative envers les États-Unis et positive envers la Chine. Les enquêtes révèlent également que les presses chinoises sélectionnées adoptent principalement la position médiée selon des schémas hétéroglosses tandis que les médias anglais ont tendance à utiliser des monoglosses. On fait valoir que les raisons possibles d’une telle déviation de position s’avèrent notamment les tendances idéologiques des médias, les différents lecteurs et leurs attentes à l’égard des médias américains et chinois, et les différentes croyances socioculturelles entre les deux pays.

Mots-clés :

- évaluation,

- conflit commercial,

- titres de l’actualité,

- transédition,

- médiation de position

Resumen

Este artículo estudia la postura mediada en los titulares de noticias transeditados sobre el conflicto comercial China-EE. UU. De 2018. Se basa en la teoría de la evaluación desarrollada por Martin y White (2005) para examinar la posición del transeditor a través de un análisis de 66 titulares de noticias en inglés y 50 titulares chinos. Los textos en inglés fueron recopilados de los principales medios de comunicación estadounidenses, mientras que los textos en chino fueron elegidos de las principales prensas de China. El resultado del análisis muestra que cuando los titulares de las noticias se transeditan del inglés al chino, la mediación de la postura normalmente suena negativa hacia Estados Unidos y positiva hacia China. Las investigaciones también encuentran que las prensas chinas seleccionadas adoptan predominantemente la postura mediada en patrones heteroglosos, mientras que los medios de comunicación en inglés tienden a usar monoglosios. Se argumenta que las posibles razones para tal desviación de postura pueden incluir tendencias ideológicas de los medios, diferentes lectores y sus expectativas de los medios estadounidenses y chinos, y las diferentes creencias socioculturales entre los dos países.

Palabras clave:

- evaluación,

- conflicto commercial,

- titulares de noticias,

- transedición,

- postura de meditación

Article body

1. Introduction

The importance of news headlines resides in the multifunctional role they play between news stories and readers (Zhang 2013). According to Valdeón (2007: 155), news headlines have “informative” and “persuasive” functions and, furthermore, transedited news headlines might have different functional implications “with regards to the target language readership.” In addition, news headlines “provide a concise and value-laden indication of a publication’s stance on a particular issue” (Spoonley 1990: 33). Zhang’s (2013) research has explored stance manifestation in news headlines through attitudinal discourses and news stance mediation in transedition. Based on previous research, especially that by Zhang (2013), this paper sets out to investigate transedited news headlines on the 2018 China-U.S. trade conflict, delving into how stance is mediated and taken by the Chinese media.

It is necessary to clarify two key concepts related to this research. The first is the notion of transediting. As some scholars have pointed out, news translation is “a particular combination between editing and translation” (Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 64), which involves “a complex, integrated combination of information gathering, translating, selecting, reinterpreting contextualizing and editing” (Van Doorslaer 2010: 181). The complicated process in news translation coincides with the term transediting, which refers to the “grey area between translating and editing” (Stetting 1989: 371), and encapsulates adaptation for purposes such as expression efficiency, realizing the intended function of the target text, and meeting the needs and conventions of the target culture (Stetting 1989: 377). Such a view was recognised by Bielsa and Bassenett (2009: 63) who found that “news translation entails a considerable amount of transformation of the source text which results in the significantly different content of the target text” and that the process of news translation is “not dissimilar from that of editing.” Our pilot study also finds that any piece of a Chinese transedited news report may come from more than one corresponding English news text. Therefore, the term transediting is applied here to refer to the transformational process of news headlines from English into Chinese.

Another theoretical concept applied in our analysis is that of mediation. Translation per se is considered a kind of mediation in which the translator “intervene[s] in the transfer process, feeding their knowledge and beliefs into their processing of a text” (Hatim and Mason 1997: 147). Mediation is also frequently mentioned in news translation, which is referred to as “the intervention of the translator by feeding his own knowledge and beliefs in the process of rendering or reconstructing a text into another language” (Pan 2012: 82). More specifically, as pointed out by Zhang (2013: 398), mediation means that the “transeditor intervenes, rewrites or manipulates in the transediting process, with an effort to accommodate in the target text stances dissenting from those in the original text.” Drawing on these previous definitions, this study regards mediation as a kind of intervention performed by the transeditor on behalf of the medium he/she works for to adjust the news stance.

2. Stance and Appraisal Framework

The term stance is ambiguous; it generally refers to “the expression of an author’s or speaker’s attitudes, feelings, judgments, or commitment concerning the message” (Biber and Finegan 1988: 1) and a public act by a social actor to evaluate objects (Du Bois 2007). In the domain of news discourse analysis and translation, it can be broadly regarded as the opinion held by certain journalistic institutions towards specific events. It is normally analysed within the Appraisal Framework (see for instance Martin and White 2005; Bednarek 2006; Munday 2012; Zhang 2013; Pan 2012, 2015; Qin 2018), which will be introduced below.

Appraisal refers to as the “semantic resources used to negotiate emotions, judgements and valuations, alongside with resources amplifying and engaging with these evaluations” (Martin 2000: 145). The Appraisal Framework “provides techniques for the systematic analysis of evaluation and stance as they operate in whole texts and in groupings of texts from any register” (White 2002: 1). It consists of three sub-systems: attitude, engagement, and graduation. In this paper, the attitudinal and engagement sub-systems will be adopted as the analytical tool to investigate the mediated stance in transedited news headlines on the 2018 China-U.S. trade conflict.

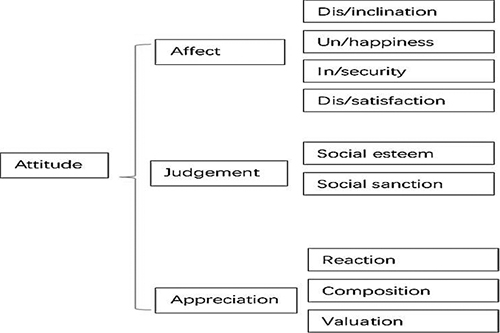

Attitude concerns “our feelings, including emotional reactions, judgments of behaviour and evaluation of things” (Martin and White 2005: 35). It is “the activation of positive or negative positioning” (White 2014: 16)[1]. Attitudinal resources can be classified into three categories: affect, judgement, and appreciation (see Figure 1). According to Martin and White (2005: 42), affect “is concerned with registering positive and negative feelings: do we feel happy or sad, confident or anxious, interested or bored?” while judgement “deals with attitudes towards behaviour, which we admire or criticize, praise or condemn.” The latter can be further divided into social esteem and social sanction. As for appreciation, it “involves evaluations of semiotic and natural phenomena, according to the way in which they are valued or not in a given field” (Martin and White 2005: 43), which contains reaction, composition, and valuation. In other words, the attitudinal resources provide different detailed evaluative mechanisms to instantiate various journalistic opinions.

Additionally, in terms of the value position of attitudinal meanings, Bednarek (2008) classifies it into three categories: positive, negative, and neutral. Huan (2018: 24) adopts a similar trichotomy in his research on journalistic stance and further defines the neutral meaning as “based on the ground that some emotions are not clearly positive or negative although they are still references to emotion.” In other words, neutral meanings are those that fall somewhere between the positive-negative cline. We consider this classification reasonable. Therefore, in this paper, we will adopt this trichotomy of value position and categorize attitudinal meanings into positive, negative and neutral.

Figure 1

Attitude sub-system in Appraisal theory (based on Martin and White 2005: 48-56)

Engagement is a “cover-all term for resources of intersubjective positioning” (White 2003: 260) and it is concerned with “the linguistic resources by which speakers/writers adopt a stance towards to [sic] the value positions being referenced by the text and with respect to those they address” (Martin and White 2005: 92). It provides a social dialogic perspective on “whether or not and how speakers acknowledge alternative positions to their own” (Martin and White 2005: 36-37). Within engagement, utterances can be divided into monoglossic and heteroglossic (see Figure 2).

Utterances deemed monoglossic usually take the form of the barely asserted proposition within which “the speaker/writer presents the current proposition as one which has no dialogistic alternatives which need to be recognised, or engaged with, in the current communicative context” (Martin and White 2005: 99). In broad terms, monoglossic utterances can be considered devices with which the media adopt a certain stance without making references to any other voices.

Heteroglossia refers to overtly dialogic locutions, which can be divided into two main categories: dialogic contraction and dialogic expansion. As Martin and White (2005: 102) explain, dialogic contraction aims to “challenge, fend off or restrict” the scope of “dialogically alternative positions and voices,” while dialogic expansion “actively makes allowance” for such scope. Dialogic contraction can be classified into disclaim and proclaim. The disclaim sub-category refers to “meanings by which some dialogic alternative is directly rejected or supplanted, or is represented as not applying” (Martin and White 2005: 117). There are two sub-types of disclaim: deny and counter. The first takes the form of negation, such as no, don’t, ever, and so forth, while the second includes “formulations which represent the current proposition as replacing or supplanting” (Martin and White 2005: 120), such as even though, although, and the like. In the proclaim category, there are three sub-types: concur, pronounce, and endorse. The concur sub-type includes forms that “overtly announce the addresser as agreeing with, or having the same knowledge as, some dialogic partner” (Martin and White 2005: 122); this is conveyed through forms such as of course, naturally, and so on. The pronounce sub-type contains “formulations which involve authorial emphases or explicit authorial interventions or interpolations” (Martin and White 2005: 127), which include locutions such as I contend…, the truth is…, and so forth. The endorsement sub-type is referred to as a formulation “by which propositions sourced to the external sources are construed by the authorial voice as correct, valid, undeniable or otherwise maximally warrantable,” which include locutions such as show, prove, etc.

Dialogic expansion includes two categories: entertain and attribution. The first includes “those wordings by which the authorial voice indicates that its position is but one of a number of possible positions” (Martin and White 2005: 104), with formulations such as possibly, probably, and so forth. The second, attribution, covers those formulations that “disassociate the proposition from the text’s internal authorial voice by attributing it to some external source” (Martin and White 2005: 111). This category can be further divided into two sub-types, acknowledge and distance. The acknowledge sub-type contains “those locutions where there is no overt indication, at least via the choice of framer, as to where the authorial voice stands with respect to the proposition,” which usually takes the form of reporting verbs, such as say, report, declare, and so forth. The distance sub-type involves utterances “in which via the semantics of the framer employed, there is an explicit distancing of the authorial voice from the attributed material,” which is typically realised through the reporting verb claim and by specific utilization of “scare” quotes (Martin and White 2005: 113). In summary, via heteroglossic devices, media present their stance in a non-self-claimed and dialogic way.

Figure 2

Engagement system in Appraisal theory (based on Martin and White 2005: 134)

As an analytical tool, Appraisal theory has been widely used by scholars to investigate journalistic discourse. White (2012) explored attribution and attitudinal positioning in hard news. Stenvall (2014) delved into the stance on affect that news agency journalists took by further classifying the affect component within the Appraisal Framework. Tavassoli, Jalilifar, et al. (2018) adopted the Appraisal Framework, especially the attitudinal resources, to investigate the stance taken by major British newspapers towards Middle-Eastern refugees. In the domain of transedition of journalistic discourse, mediated stance has become a core topic. Zhang (2013) applied the attitudinal system to investigate mediated stance in the transedited news headlines of international news. Pan (2015) drew on Appraisal theory, especially the graduation system, to investigate news related to human rights issues in China and reported by major Anglophone news agencies, namely how these were translated by China’s state-run media. Kamyanets (2019) relied on Appraisal theory’s attitudinal system to explore the evaluative language of a Ukrainian magazine and of its English version, finding that the translated version is usually attitudinally less negative.

In sum, stance is understood as the positive, neutral or negative viewpoint of the media towards certain people, behaviours, events or objects. It is closely related to appraisal because, on the one hand, it is instantiated through different evaluative mechanisms within attitudinal resources and, on the other hand, it is taken via various engagement devices in either a monoglossic or heteroglossic way. In transedition, mediated stance is instantiated via deviated attitudinal resources and is taken through different engagement devices. Previous research has mostly focused on how mediated stance is instantiated through the transformation of attitudinal resources in news transedition, but has rarely paid attention to the issue of how such a mediated stance is taken. The present study attempts to fill this research gap by combining the attitudinal and engagement systems to investigate news headlines and scrutinise this under-researched issue.

3. Research data and methodology

This study investigates news headlines on the 2018 China-U.S. trade conflict and their transedited versions in Chinese media. The trade dispute between China and the United States was ignited on March 23, 2018, after Donald Trump signed a memorandum to impose a 25% tariff on $50 billion (U.S.) worth of Chinese imports. After this, the Chinese government raised retaliatory tariffs on American imports. The trade war intensified soon after the U.S. Commerce Department banned ZTE, a Chinese telecommunications equipment and systems company, from doing business with American companies for seven years. The trade dispute seemed to cool down when a U.S. delegation arrived in Beijing in June of 2018 to start negotiations. However, soon after, the Trump administration declared a further 25% tariff on $50 billion (U.S.) worth of Chinese goods, leading China to immediately retaliate. The tension did not abate until both sides agreed to a truce at the end of 2018. But, at about the same time, Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO and daughter of company founder Ren Zhengfei, was arrested by the Canadian authorities at the request of the U.S. In a very short time, negotiations between China and the U.S. were affected and the trade war intensified despite the “truce.”

The data for this study consist of 50 Chinese news headlines and 66 English headlines published between March 18, 2018 and December 22, 2018. When collecting data, we first gathered the Chinese headlines as transedited texts, from which we then retrieved the corresponding English headlines as source texts. It should be pointed out that the numbers of English and Chinese headlines are not equal because, as has been mentioned above, they are transedited from English into Chinese. One Chinese headline may contain information from two or more English headlines. In terms of data sources (see Table 1), the Chinese headlines were collected from media such as Reference News [参考消息] and Global Times [环球网].Reference News is a Chinese newspaper authorised to publish foreign news. It is run by the Xinhua News Agency, an institution affiliated with the Chinese State Council, and, as such, it is the mouthpiece and information collector of the Chinese central government. Global Times, run by the People’s Daily, is the official news outlet of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. It is another newspaper authorised to transmit international news in China. Other news media, such as Sina.com and Ifeng.com, are among the most influential news outlets in China and they are supervised by the news administration departments of the Chinese government. The English news headlines were collected from major media in the United States, such as The Wall Street Journal, TheNew York Times, and Bloomberg. The detailed number of news reports are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

The number of articles from different media

In our research, the attitudinal and engagement devices in both the English and Chinese versions of the headlines were first identified and quantified. Then, a qualitative analysis was conducted on the stance mediation instantiated in these evaluative resources. For the quantitative analysis, NVivo 11[2] was employed to code and calculate the data. The following example is to illustrate how appraisal resources are coded.

Table 2

Evaluative devices in Example 1

Table 2 gives an example of how we analyse the appraisal devices in the news text. It shows that the English version states Trump’s approval of tariffs on China; the Chinese version demonstrates concern over the negative effects of the trade war on the global economy and criticises America’s behaviour. In terms of stance, the English headline contains a neutral judgement on Trump’s decision, instantiating a neutral stance towards the U.S. (Trump… to impose tough China tariffs), while the Chinese version conveys a negative attitude, instantiated by a negative judgement: [America’s way of doing things is very indecent]. Additionally, with regard to engagement, the English version resorts to a monoglossic device while the Chinese headline uses a heteroglossic one, attributing the proposition to an external source by the sub-device of acknowledge ([The world is worrying…], [Foreign media…]).

The stances identified in the news under investigation are classified into six modes: positive stance towards the U.S. (positive-U.S. stance), neutral stance towards the U.S. (neutral-U.S. stance), negative stance towards the U.S. (negative-U.S. stance), positive stance towards China (positive-China stance), neutral stance towards China (neutral-China stance), and negative stance towards China (negative-China stance). The engagement devices are divided into two categories: monoglossic and heteroglossic. Later, these verbal resources were coded accordingly in their corresponding nodes in NVivo 11 for quantitative analysis.

4. Results and case analysis

Following the coding method mentioned above, the attitudinal resources adopted by both U.S. and Chinese media will firstly be identified and calculated to demonstrate possible stances instantiated by relevant devices. Then the quantification of the engagement devices will be scrutinised to investigate how Chinese media take the mediated stance.

4.1. Quantification results of stance mediation

Figure 3 shows the stances in both English and Chinese news headlines. It can be seen that in the English news headlines, the most prominent is the negative-U.S. stance with 33 occurrences. The negative-China stance and neutral-U.S. stance make up a considerable amount with 12 and 8 instances respectively. However, very few positive-U.S. (3 instances) and positive-China (6 instances) stances are reported by the American media. There are 8 occurrences of neutral stance towards the United States and 4 towards China. The Chinese news headlines contain an equally prominent number of occurrences (35) of negative-U.S. stance. There are 9 positive-China and 2 positive-U.S. stance occurrences in the Chinese headlines, and 6 instances of neutral stance towards the U.S. and 4 towards China.

Figure 3

Stance in English and Chinese news headlines

Figure 4 shows the most prominent stance meditation modes in the transedited news headlines. The primary mode retains the negative-U.S. stance (Neg U.S. to Neg U.S.) in the Chinese news headlines with 35 occurrences; other noticeable modes are changing a neutral stance to a negative stance towards the United States (Neu U.S. to Neg U.S.) and changing a negative-China stance into a negative-U.S. stance (Neg CHN to Neg U.S.), each occurring 7 times. Moreover, shifting a negative-U.S. stance into a positive-China stance (Neg U.S. to Pos CHN), something which should not be ignored, occurred 6 times. Generally speaking, a negative stance towards the U.S. and a positive towards China is the most apparent mode in stance mediation.

Figure 4

Stance mediation modes in transedition

Figure 5 demonstrates the media’s engagement in taking the mediated stances. It shows that the English news headlines take both monoglossic and heteroglossic devices to manifest their stance-taking, with 39 and 27 occurrences respectively. In the Chinese news headlines, however, heteroglossia is the most commonly seen device with 49 occurrences, but monoglossia is rarely used, with only 1 occurrence. Therefore, changing monoglossia to heteroglossia and retaining heteroglossia are the major stance-taking patterns in the transedited Chinese news headlines under investigation.

Figure 5

Engagement devices in English and Chinese news headlines

After quantifying the engagement devices used in English and Chinese news headlines, we examined the correlation between the stance mediation modes and stance-taking patterns. Due to limited space, Figure 6 only presents the 4 most prominent stance mediation modes: Neg U.S. to Neg U.S., Neu U.S. to Neg U.S., Neg CHN to Neg U.S., and Neg U.S. to Pos CHN. It shows that in the Neg U.S. to Neg U.S. mode, the monoglossic to heteroglossic pattern is the mostly applied (23 instances). Such a stance taking pattern can also be found in the mediated stance modes of Neu U.S. to Neg U.S. and Neg CHN to Neg U.S. (6 instances). However, in the Neg U.S. to Pos CHN mode, two patterns are evenly adopted: monoglossia to heteroglossia and retaining heteroglossia. Generally, the mediated stance towards the United States is usually negative and the stance towards China is usually positive. This negative-U.S./positive-China stance is dominantly taken via the pattern of monoglossia to heteroglossia. The following section will provide a detailed case analysis to illustrate the detailed deviations.

Figure 6

Stance mediation modes and stance-taking patterns in transedition

4.2. Case analysis

This section will give a case analysis to demonstrate how stance is mediated and taken by the Chinese media via transedition. The examples are selected from the corpus to illustrate the stance-mediation modes of Neg U.S. to Neg U.S., Neu U.S. to Neg U.S., Neg CHN to Neg U.S. and Neg U.S. to Pos CHN, as well as the stance-taking measures via engagement devices.

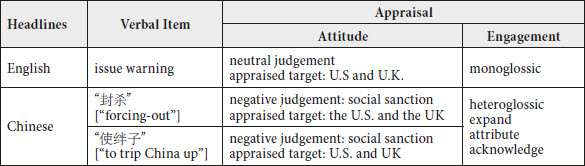

Table 3

Retaining negative-U.S. stance

Example 2 is collected from news headlines on the United States’ request to arrest Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO. Both English headlines demonstrate a negative-U.S. stance in this incident. In the first English headline, TheWashington Post uses the expression an idiotic way, a negative judgement on social esteem, to comment on the U.S.’s behaviour, and such a negative stance is taken in a monoglossic way, categorically construing the stupidity of arresting Huawei’s top executive. In the second English version, TheNew York Times also expresses a negative judgement, questioning Donald Trump’s ability to deal with China-related trade issue. Such a stance is advanced in a heteroglossic way by using an endorsement of a proclamation, through which a negative evaluation towards Trump is construed as undeniable.

In the Chinese headline, the negative-U.S. stance is retained. As the first English headline does, the Chinese version also regards the United States’ action as 愚蠢 [idiotic]. Additionally, the Chinese headline makes a condemning evaluation of the propriety of arresting Meng Wanzhou, using 对华为下手 [targeting Huawei as prey] and 错误 [wrong], which are a negative social sanction. However, such a stance is taken via the means of acknowledge, attributing the negative stance to the U.S. media and making space for the putative reader who may hold different views.

Table 4

Mediating neutral-U.S. stance to negative-U.S. stance (monoglossic to heteroglossic)

Example 3 is taken from a news report on the attempt of the United States to ban ZTE, a Chinese telecommunication technology company, from doing business with U.S. companies. With neutral judgement, the English news headline conveys a neutral stance towards the United States and the United Kingdom, and it is adopted in a monoglossic utterance.

In the Chinese transedited headline, the neutral stance is mediated into a negative one. Two evaluative items can be detected: 封杀 [forcing-out] and 使绊子 [try to trip China up]. The first is a negative judgement, which indicates that the UK and U.S.’s attempt to “force out” China violated free-trade principles. The second is also a negative judgement on social sanction that directly criticizes the U.S. and UK’s morally inappropriate banning ZTE. Global Times takes such a mediated stance by attributing it to external sources: foreign media. It aligns putative readers with the negative stance towards the United States by acknowledging that even foreign media have regarded America’s action as inappropriate, even though it might be one of the various stances of different sources.

Table 5

Mediating neutral-U.S. stance to negative-U.S. stance (heteroglossic to heteroglossic)

In the English version of Example 4, the phrase could seek a China trade truce is a neutral judgement on the social esteem of the U.S. government, represented by Trump, implying that there is a possibility that a truce could be achieved so as to avoid the aggravation of the trade war. Such a stance is advanced in a heteroglossic way via the entertain device, which indicates that such a neutral stance is a range of possible value positions in Trump’s solution to China’s trade conflict.

In the Chinese version (4a), the negative-U.S. stance is instantiated by the comment “必赢不输”纯属幻想 [“sure-win and no-lose” is a sheer fantasy]. This comment shows a negative appreciation of the value of the thought held by the U.S. government, namely that they can win in the trade conflict. Reference News takes that kind of view as 纯属幻想 [a sheer fantasy]. The negative-U.S. stance is taken in a heteroglossic way by attributing such a value position to the U.S. media, implying that such a negative evaluation is but a series of possible negative attitudes held by the media in the United States.

Table 6

Mediating negative-China stance into negative-U.S. stance

Example 5 consists of the news headlines on the progress of the China-U.S. trade negotiation held in Washington. In the trade conflict, the U.S. compelled China to increase imports so as to reduce the U.S.-China trade deficit, but China withstood the pressure. Therefore, giving in to U.S. demands may be seen as a major failure on the part of China. In the first English version, the statement China agrees to buy more U.S. goods and services is a seemingly factual description. Nevertheless, such a headline may instantiate a subtle negative-China stance, because it conveys a negative judgement on social esteem, implying that China has conceded to the United States and agreed to import more American commodities, as the U.S. demanded. It is the same in the second English version, which also subtly advances a negative-China stance by negatively evaluating China’s ability in the negotiations. The negative stance in the first English version is taken in a monoglossic communicative setting in the form of a bare assertion, while in the second English version, such a stance is attributed to Kudlow, indicating that Bloomberg may want to remain distant from such an evaluation.

In the Chinese headline, Reference News on the one hand delicately expresses a positive-China stance by presenting China’s non-conceding attitude in the trade negotiation. On the other hand, it also holds a negative stance towards the United States by commenting that the U.S.’s demand is “unreasonable,” which is a negative judgement with social sanction, and that it considers the demand an inappropriate action. Such a stance is attributed to foreign media, creating dialogical space for putative readers to align them with this evaluation.

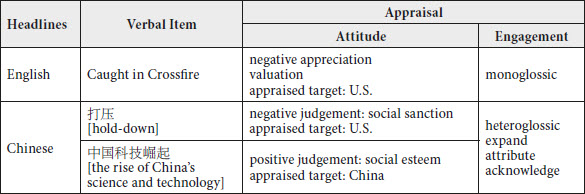

Table 7

Mediating negative-U.S. stance into positive-China stance (monoglossic to heteroglossic)

Example 6 is excerpted from a piece of news on the U.S. government’s sanction on ZTE. In the English version, The Wall Street Journal holds a negative stance towards such punishment, and it claims that U.S. tech firms are severely affected; they are “caught in [a] crossfire” and suffer collateral damaged. The phrase caught in [a] crossfire is a negative appreciation of the situation in which U.S. tech firms were trapped because of the trade conflict. The negative stance is presented in a monoglossic way in the form of a “pseudo” question, implying that there is no dialogical alternative to be recognised.

In the Chinese version, Global Times expresses the negative attitude towards the U.S. by describing their behaviour as 打压 [hold-down] and their reaction as 恐慌 [panic]. Moreover, a positive stance towards China is instantiated via the attitudinal item 中国科技崛起 [the rise of China’s science and technology], which is a positive judgement on China’s capability in the hi-tech domain. Such a positive stance is conveyed in a heteroglossic way by acknowledging the value position of the American media.

Table 8

Mediating negative-U.S. stance into positive-China stance (heteroglossic to heteroglossic)

Example 7 illustrates how a negative-U.S. stance is mediated into a positive stance towards China via a heteroglossic to heteroglossic means. The English version indicates a negative-U.S. stance by describing the outcome of banning ZET as backfire. Such a negative judgement is advanced through a heteroglossic device: indicating that an adverse effect is but one of the possible consequences of sanctions against ZET.

In the Chinese headline, a positive-China stance is instantiated by the phrase 中国科技发展更快 [accelerate China’s science and technology], which conveys a positive judgement of China’s ability to cope with America’s sanctions. Instead of indicating a range of possibilities, the Chinese version attributes this stance to the American media while maintaining an independent position as a simple conveyer of information.

5. Discussion

In the above section, the four most prominent stance-mediation modes have been identified and analysed: Neg U.S. to Neg U.S., Neu U.S. to Neg U.S., Neg U.S. to Pos CHN, and Neg CHN to Neg U.S. Stance-taking measures via engagement devices were also identified and analysed. With regard to possible causes for manipulation in news transedition, Qin and Zhang (2018) have explored and summarised influential factors such as target readership, political situation, and political position of the media. Based on previous research, we will further explore and discuss the possible constraints behind the mediated stance.

5.1. Different ideological tendencies: is the trade war a righteous counterattack or trade bullying?

Ideology “can be taken to mean a set of ideas or a belief system” (Stevenson 2002: 228) that “shapes people’s sense of reality, provides them with a taken for granted frame for judging what is good and bad or right and wrong in that reality, and enables and constrains their thinking about what realities are possible” (Mumby and Kuhn 2019: 252). Liberalism and conservatism are the two most distinct ideological tendencies in U.S. society (Qian 2007; Zhang 2012), but no consensus has been reached on the ideological tendencies of the U.S. media. However, a survey conducted by Gallup,[3] a public polling institute, indicated that in the economic sphere, the mainstream U.S. media tend to hold a conservative position. Generally speaking, American economic conservatism supports “the free economic system” (Schneider 2009: xiii) by upholding both limited government regulation of business investment and free enterprise. One of America’s fundamental goals in the trade war is to halt the “Made in China 2025” strategy. According to the Council on Foreign Relations,[4] an American think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international affairs, this strategy is believed to be achieved through substantial government subsidies to Chinese enterprises and forced technology transfer, which violates America’s conservative economic principles. With this perception, the mainstream media may sometimes hold a neutral stance towards the U.S. government, even if a negative attitude is the principal evaluation of the Trump administration. Example 3 is a case in point, in which the media take a neutral stance to the banning of ZTE, because this company has been receiving large subsidies from the Chinese government, something that goes against U.S. conservative economic principles.

Since Xi Jinping came into power, the Chinese Dream has become the core of China’s mainstream ideology (Hao 2014; Li 2015). The ultimate goal of such an ideology is to achieve a national rejuvenation. This goal is deeply rooted in the historical background of China’s decline and humiliation caused by foreign invasions between the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. Therefore, patriotism and nationalism are re-accentuated in China’s present mainstream ideology. In the Chinese perspective, the trade war is regarded as a foreign intervention similar to what their forefathers suffered centuries ago and is termed 贸易霸凌 [trade bullying] (Yang 2018: 11). America’s trade bullying is characterized by violation of international trade rules and aims to curb China’s development (Dai, Zhang, et al. 2018). Therefore, the U.S. may be compared to the imperialist power that brought humiliation to China centuries ago. This conception may be responsible for the mediation of a neutral-U.S. stance to a negative-U.S. stance, especially the emphasis on the immorality of the trade war. The Chinese headline in Example 3, in which the banning of ZTE is depicted as an immortal activity, illustrates this case well.

5.2. Different institutional roles: attack dog or mouthpiece?

The role played by the American media against the U.S. government has evolved from lapdog to watchdog, and, ultimately, to attack dog. The lapdog role played by the U.S. media is illustrated by their close cooperation with the U.S. government during the two World Wars, in which they totally and uncritically accepted the government’s policies. The watchdog role is characterized by concealing news, especially those unfavourable reports on the Vietnam War in the 1960s. However, the attack dog role implies a confrontation between U.S. media and their government, such as the Watergate scandal in the 1970s (Straubhaar and LaRose 2002). In addition, researchers (see for instance Ming 2005) have found that after the events of 9/11, the U.S. media played another role, that of sheepdog for the government, offering justifications for the Iraqi War and shaping public opinions. However, the interdependent relationship between the U.S. media and government was destroyed when Donald Trump won the presidential election and came to power in 2016. The confrontation between the Trump administration and mainstream American media has magnified the adversarial aspect of the relationship between the government and the media (Zhao 2018), re-establishing an attack dog role for the latter. This role may account for the prominent occurrence of a negative-U.S. stance in the English news headlines. Such a stance is often instantiated via a negative judgement on the social esteem of the Trump administration, criticising their incompetence in the trade conflict. Example 2 is a case in point. It should also be noted that such a stance is usually taken up monoglossically and declared in a categorically assertive way, projecting Trump’s incompetence in the trade conflict as fact.

There is a consensus that China’s state-run media are under the guidance and supervision of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese central government (Lu 1980; Li 2003; Qin 2018; among others). The Chinese headlines in the current study are collected from media sources affiliated with either the Xinhua News Agency or The People’s Daily, the two most important mouthpieces for the CPC and the Chinese central government. According to the Xinhua News Agency[5] and The People’s Daily,[6] the duty of these mouthpieces can be summarised as to “firmly grasp correct political direction and opinion orientation and loyally perform the function as ‘mouthpiece’” (our translation)[7] and to “vigosrously publicise CPC’s theories, lines, guidelines and policies, as well as CPC’s major decisions” (our translation)[8]. Therefore, instead of taking an adversary position against the government, the Chinese state-monitored media are oriented to stay in line with the stance of the CPC and the Chinese central government. Thus, in the case of reporting on a China-U.S. trade conflict, there are frequent occurrence of a negative-U.S. stance in the Chinese version, because the trade conflict is regarded as unilateralism and trade protectionism (Dai, Zhang, et al. 2018), which is vehemently opposed by the Chinese government.[9]

The mouthpiece orientation requires Chinese state-monitored media to establish a positive national image of China (He 2009). This may contribute to the prominent use of heteroglossic devices in the Chinese news headline. As we have discovered in the above sections, acknowledge is the most commonly used engagement measure in the Chinese headlines. Via such devices, the Chinese media appear to remain distant from the value position conveyed in the headline and seem to act as impartial messengers who are simply conveying the views of the U.S. media. In other words, by using heteroglossic devices, the Chinese media want to show that any positive assessment of China’s role in the trade conflict is not self-claimed, but has been acknowledged even by their U.S. counterparts. By doing so, the Chinese media constructs a narrative in which Trump triggering the trade war was opposed not just by China, but also by the U.S. people. As such, China is portrayed as the righteous side in the conflict, because it supposedly stands in line with both the Chinese and American people for the greater good.

5.3. Different socio-cultural beliefs: is China collapsing or rising?

The attack dog role played by mainstream American media does not necessarily mean that China, the opponent in Trump’s trade war, is described in a positive light. In the above sections, there are occurrences of a negative-China stance held by the American media. Such a stance may echo the so-called “China collapse” theory which has long existed in American society. This theory was proposed in the early 1990s and has become more prominent in recent years as China’s economic growth slowed. For instance, writing for The Wall Street Journal, Shambaugh (2015)[10] claims that CPC’s rule in China will soon end. Such pessimistic predictions have also spread to the economic realm. For example, writing for Brookings, Kroeber (2016)[11] asserts that China’s economy is greatly troubled. This “China collapse” theory may account for some of these occurrences of a negative-China stance in the U.S. media and a negative attitude towards China in news headlines. The English headlines in Example 5 are a typical case. One of the demands of the U.S. government in the trade conflict is to reduce China’s trade surplus. By reporting that China agreed to U.S. terms and would buy more American goods, the media may imply that the Chinese government lost ground in the trade conflict, thus echoing the “China collapse” perception of American society.

In recent years, especially since Xi Jinping came to power, the perception of “a new era” has prevailed in China. China’s “new era” means that “the Chinese nation, which suffered a lot in early modern times, has ushered in a great historic leap, grown rich and become strong”[12] (Bao 2018: 20; our translation). In contrast to the “China collapse” expectation of the West, in Chinese society, China is depicted as a country whose overall strength is equal to that of the U.S. It is widely believed that the trade war triggered by Trump has failed and that it will otherwise accelerate China’s development. This is illustrated by Examples 6 and 7, in which a negative-U.S. stance is changed into a positive-China stance, foregrounding China’s competitive nature in the realm of science and technology and the adverse effect of Trump’s hostile action towards China.

6. Concluding remarks

By adopting Martin and White’s (2005) Appraisal theory, this paper has investigated 66 English news headlines on the 2018 China-U.S. trade conflict and their Chinese transedited versions. It has found the following trend in the transedited headlines: a negative-U.S. and a positive-China stance. Moreover, it has shown that the selected Chinese presses tend to change monoglossic devices into heteroglossic ones when they take such a mediated stance in transedition. Finally, it argues that the possible factors leading to such deviations may include different media ideological tendencies, different institutional roles for the American and Chinese media, and different socio-cultural beliefs in these two countries.

Appendices

Appendix

Corpus references

Anonymous (17 April 2018): 彭博社:美国政府封杀中兴只会令中国科技发展更快 [Bloomberg: The U.S. government’s forcing-out of ZTE can only accelerate China’s science and technology]. Sina.com. Consulted on 3 March 2020, <http://tech.sina.com.cn/t/2018-04-17/doc-ifzihnep1003211.shtml>.

Banjo, Shelly (17 April 2018): How the U.S. Ban Against ZTE Could Backfire. Bloomberg. Consulted on 2 March 2020, <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-04-17/how-the-u-s-ban-against-zte-could-backfire>.

Davis, Bob and Wei, Lingling (18 May 2018): China Agrees to Buy More U.S. Goods and Services. The Wall Street Journal. Consulted on 1 March 2020, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-drops-probe-into-u-s-sorghum-shipments-1526629000>.

Dong, Lei (20 May 2018): 外媒关注中美经贸谈判获进展:中方拒绝美不合理要求 [Foreign media pay attention to the progress made in China-U.S. trade negotiation: the Chinese side refuses America’s unreasonable demand]. Reference News. Consulted on 28 February 2020, <http://www.cankaoxiaoxi.com/china/20180520/2271867.shtml>.

Douglas, Jason and Wall, Robert (16 April 2018): U.S., Britain Issue Warnings Over Chinese Telecom Equipment Maker ZTE. The Wall Street Journal. Consulted on 5 March 2020, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-britain-issue-warnings-over-chinese-telecom-equipment-maker- zte-1523898318>.

Ford, Lindsey and Cutler, Wendy S. (8 December 2018): Huawei Arrest Shows Trump Has No Game Plan Against China. The New York Times. Consulted on 28 April 2020, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/08/opinion/huawei-arrest-trade.html>.

Jia, Yuanxi (16 June 2018): 世界担忧贸易紧张升级 外媒:美国做法很不体面 [The world is worrying about the escalation of the trade tension. Foreign media: America’s way of doing things is very indecent]. Reference News. Consulted on 3 March 2020, <http://www.cankaoxiaoxi.com/china/20180616/2281360.shtml>.

Karabell, Zachary (8 December 2018): Prosecuting the Chinese Huawei executive is an idiotic way to hold China in check. The Washington Post. Consulted on 4 March 2020, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2018/12/08/prosecuting-chinese-huawei-executive-is-an-idiotic-way-hold-china-check/>.

Landler, Mark (27 November 2018): Trump Could Seek a China Trade Truce at G-20, Despite Tough Talk. The New York Times. Consulted on 3 March 2020, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/us/politics/trump-xi-trade-g-20.html>.

Li, Sai (30 November 2018): 美媒呼吁谈判解决对华贸易摩擦:“必赢不输”纯属幻想 [The U.S. media appeal to settle the trade friction with China via negotiation: “sure-win and no-lose” is a sheer fantasy]. Reference News. Consulted on 2 March 2020, <http://www.cankaoxiaoxi.com/china/20181130/2360662.shtml>.

Li, Shengyi (17 April 2018): 外媒:美英“封杀”中兴 给中国“使绊子” [Foreign media: U.S. and UK’s “forcing-out” of ZTE tries to “trip China up”]. Global News. Consulted on 27 April 2020, <https://oversea.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnK7ONK>.

Sink, Justin (18 May 2018): Kudlow Says China Offered ‘at Least’ $200 Billion in New Trade. Bloomberg. Consulted on 2 March 2020, <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-18/kudlow-says-china-offered-at-least-200-billion-in-new-trade>.

Thomas, Ken and Wiseman, Paul (14 June 2018): Trump approves plan to impose tough China tariff. AP News. Consulted on 1 March 2020, <https://apnews.com/cd0311af996d4a888d52e5fd18d187a4/Trump-approves-plan-to-impose-tough-China-tariffs>.

Wang, Lulu (10 December 2018): 美媒:美国针对华为下手错误且愚蠢 [United States media: the United States targeting Huawei as prey is wrong and idiotic]. Reference News. Consulted on 5 March 2020, <http://www.cankaoxiaoxi.com/china/20181210/2364509.shtml>.

Wei, Shaopu (22 April 2018): 美媒:美国打压中兴源于对中国科技崛起的恐慌! [U.S. media: America’s holding-down of ZET is rooted in the panic of the rise of China’s science and technology!]. Global News. Consulted on 1 March 2020, <https://world.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnK7V2g>.

Wong, Jacky (17 April 2018): U.S. Tech Caught in Crossfire of China Trade Fight. The Wall Street Journal. Consulted on 27 February 2020, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-tech-caught-in- crossfire-of-china-trade-fight-1523956786>.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Start-up Project of Guangxi University for Nationalities (2019SKQD17).

Notes

-

[1]

White, Peter R. R. (2014): The attitudinal work of news journalism images – a search for visual and verbal analogues. Quaderni del CeSLiC. Occasional papers. 6-42. Consulted on 6 February 2020, <http://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/amsacta/4110>.

-

[2]

QSR International (17 January 2017): NVivo. Version 11.4. Consulted on 14 March 2020, <http://techcenter.qsrinternational.com/desktop/nv11/nv11_toc_resources.htm>.

-

[3]

Jones, Jeffrey (25 May 2012): In U.S., Nearly Half Identify as Economically Conservative. Gallup. Consulted on 24 November 2019, <https://news.gallup.com/poll/154889/nearly-half-identify-economically-conservative.aspx>.

-

[4]

Mcbride, James and Chatzky, Andrew (13 May 2019): Is ‘Made in China 2025’ a Threat to Global Trade? Council on Foreign Relations. Consulted on 24 November 2019, <https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/made-china-2025-threat-global-trade>.

-

[5]

Xinhua News Agency (2019): 新华社简介 [Introduction to Xinhua News Agency]. Xinhua News Agency. Consulted on 29 May 2019, <http://203.192.6.89/xhs/static/e11272/11272.htm>.

-

[6]

People’s Daily (2019): 报社简介 [Introduction]. People’s Daily. Consulted on 29 May 2019, <http://www.people.com.cn/GB/50142/104580/index.html>.

-

[7]

“新华社坚持围绕中心、服务大局,牢牢把握正确的政治方向和舆论导向,忠实履行 ‘喉舌’职能.”

-

[8]

“积极宣传党的理论和路线方针政策,积极宣传中央重大决策部署.”

-

[9]

Han, Jie and Liu, Jie (24 September 2018): 中国发布《关于中美经贸摩擦的事实与中方立场》白皮书 [China releases the white paper “The Facts and China’s Position on China-US Trade Friction”]. Xinhua News Agency. Consulted on 27 May 2019. <http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2018-09/24/c_1123475262.htm>.

-

[10]

Shambaugh, David (6 March 2015): The Coming Chinese Crackup. The Wall Street Journal. Consulted o 29 February 2020, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-coming-chinese-crack-up-1425659198>.

-

[11]

Kroeber, Arthur (9 February 2016): Should We Worry About China’s Economy? Brookings Institution. Consulted on 27 May, 2019, <https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/should-we-worry-about-chinas-economy/>.

-

[12]

“近代以来久经磨难的中华民族迎来了从站起来、富起来到强起来的伟大历史性飞跃.”

Bibliography

- Bao, Xinjian (2018): 新时代的科学内涵与新思想的鲜明特质 [The scientific connotation of the new ear and the features of the new thoughts]. Contemporary World and Socialism. 1:19-25.

- Bednarek, Monika (2006): Evaluation in Media Discourse: Analysis of a Newspaper Corpus. New York/London: Continuum.

- Bednarek, Monika (2008): Emotion Talk Across Corpora. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Biber, Douglas and Finegan, Edward (1988): Adverbial stance types in English. Discourse Processes. 11(1):1-34.

- Bielsa, Esperança and Bassnett, Susan (2009): Translation in Global News. London/New York: Routledge.

- Dai, Xiang, Zhang, Erzhen, and Wang, Yuanxue (2018): 特朗普贸易战的基本逻辑、本质及其应对 [The basic logic, essence, and response of the Trump trade war]. Nanjing Journal of Social Sciences. 4:11-17, 29.

- Van Doorslaer, Luc (2010): Journalism and Translation. In: Yves Gambier and Luc Van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 180-184.

- Du Bois, John W. (2007): The stance triangle. In: Robert Englebretson, ed. Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 139-182.

- Hao, Baoquan (2014): 中国梦的意识形态话语创新 [The ideological discourse innovation of the Chinese dream]. Journal of the Party School of the Central Committee of the CPC. 18(5):27-30.

- Hatim, Basil and Mason, Ian (1997): The Translator as Communicator. London/New York: Routledge.

- He, Guoping (2009): 中国对外报道思想研究 [Policy study on reporting China for global audiences]. Beijing: Communication University of China Press.

- Huan, Changpeng (2018): Journalistic Stance in Chinese and Australian Hard News. Shanghai/Singapore: Shanghai Jiaotong University Press/Springer Nature Singapore.

- Kamyanets, Angela (2019): Evaluation in translation: a case study of Ukrainian opinion articles. Perspectives. 28(3):393-405.

- Li, Liangrong (2003): 论中国新闻媒体的双轨制—再论中国新闻媒体的双重性 [On the dual-track system of Chinese news media – a revisit on the duality of Chinese news media]. Media Observer. 3:1-4.

- Li, Zhongjun (2015): 中国梦·社会主义核心价值观·中国精神三位一体的铸魂逻辑 [The consisting of Chinese dream, the core socialist values, and the Chinese spirit]. Social Science Front. 6:9-15.

- Lu, Dingyi (1980): 我们对于新闻学的基本观点 [Our basic viewpoints to journalism]. In: Media Research Centre of CASS, eds. 中国共产党新闻工作文件汇编 [A Collection of Documents on CPC’s Journalism]. Vol. 2. Beijing: Xinhua Publishing House, 187-196.

- Martin, James R. (2000): Beyond Exchange: APPRAISAL Systems in English. In: Susan Hunston and Geoff Thompson, eds. Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse. London: Oxford University Press, 142-175.

- Martin, James R. and White, Peter R. R. (2005): The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ming, Anxiang (2005): 从“叭儿狗”到“牧羊狗”:美国传媒与政府关系的角色转变 [From “lapdog” to “sheepdog”: shifting of American media’s relationship with the government]. Journal of International Communication. 4:16-23.

- Mumby, Dennis and Kuhn, Timothy (2019): Organizational Communication: A Critical Introduction. London/Thousand Oaks/New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Munday, Jeremy (2012): Evaluation in Translation: Critical Points of Translator Decision-Making. London/New York: Routledge.

- Pan, Li (2012): Stance Mediation in News Translation: A Case Study of Sensitive Discourse on China 2008. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Macau: University of Macau.

- Pan, Li (2015): Ideological positioning in news translation: A case study of evaluative resources in reports on China. Target. 27(2):215-237.

- Qian, Kejin (2007): 美国媒体的“自由”与“保守” [“Liberalism” and “conservatism” in American media]. Youth Journalist. 5:62-63.

- Qin, Binjian (2018): Reframing News Stories for Target Readers: A Case Study of News and Translation on South China Sea Dispute. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Macau: University of Macau.

- Qin, Binjian and Zhang, Meifang (2018): Reframing translated news for target readers: a narrative account of news translation in Snowden’s discourses. Perspectives. 26(2):261-276.

- Schneider, Gregory (2009): The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Spoonley, Paul (1990): Racism, Race Relations and Media. In: Paul Spoonley and Walter Hirsh, eds. Between the Lines – Racism and the New Zealand Media. Auckland: Heinemman Reed, 26-37.

- Stenvall, Maija (2014): Presenting and representing emotions in news agency reports. Critical Discourse Studies. 11(4):461-481.

- Stetting, Karen (1989): Transediting: A new term for coping with the grey area between editing and translating. In: Graham Caie, ed. Proceedings from the Fourth Nordic Conference for English Studies. (Fourth Nordic Conference for English Studies, Elsinore, 11-13 May 1989). Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 371-382.

- Stevenson, Nicholas (2002): Understanding Media Cultures. London/Thousand Oaks/New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

- Straubhaar, Joseph and Larose, Robert (2002): Media Now: Communication in the Information Age. Stamford: Wadsworth.

- Tavassoli, Fatemeh, Jalilifar, Alireza, and White, Peter R. R. (2018): British newspapers’ stance towards the Syrian refugee crisis: An appraisal model study. Discourse & Society. 30(1):64-84.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2007): Translating News from the Inner Circle: Imposing Regularity across Languages. Quaderns. 6:155-67.

- White, Peter R. R. (2002): Appraisal: The Language of Evaluation and Stance. In: Jef Verschueren, Johan Östman, and Jan Blommaert, eds. Handbook of Pragmatics. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1-27.

- White, Peter R. R. (2003): Beyond modality and hedging: a dialogic view of the language of intersubjective stance. Text. 23(2):259-284.

- White, Peter R. R. (2012): Exploring the axiological workings of ‘reporter voice’ news stories—Attribution and attitudinal positioning. Discourse, Context & Media. 1(2-3):57-67.

- Yang, Bin (2018): 美国贸易霸凌主义背后的深层国际战略 [The in-depth international strategy behind the U.S. trade bullying]. Academic Review. 5:11-16.

- Zhao, Mei (2018): 特朗普时代的美国媒体 [American media in the Trump era]. The Journal of International Studies. 39(4):37-67.

- Zhang, Guoqing (2012): 媒体话语权:美国媒体如何影响世界 [Media’s right to speak: how American media influences the world]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press.

- Zhang, Meifang (2013): Stance and mediation in transediting news headlines as paratexts. Perspectives. 21(3):396-411.

List of figures

Figure 1

Attitude sub-system in Appraisal theory (based on Martin and White 2005: 48-56)

Figure 2

Engagement system in Appraisal theory (based on Martin and White 2005: 134)

Figure 3

Stance in English and Chinese news headlines

Figure 4

Stance mediation modes in transedition

Figure 5

Engagement devices in English and Chinese news headlines

Figure 6

Stance mediation modes and stance-taking patterns in transedition

List of tables

Table 1

The number of articles from different media

Table 2

Evaluative devices in Example 1

Table 3

Retaining negative-U.S. stance

Table 4

Mediating neutral-U.S. stance to negative-U.S. stance (monoglossic to heteroglossic)

Table 5

Mediating neutral-U.S. stance to negative-U.S. stance (heteroglossic to heteroglossic)

Table 6

Mediating negative-China stance into negative-U.S. stance

Table 7

Mediating negative-U.S. stance into positive-China stance (monoglossic to heteroglossic)

Table 8

Mediating negative-U.S. stance into positive-China stance (heteroglossic to heteroglossic)