Abstracts

Abstract

The canvas tote bag, often branded with the name and logo of a popular cultural institution or bookstore, has become a shorthand for an individual’s accumulated cultural capital; this seemingly innocuous accessory has the power to signal to one’s peers the level of their engagement with the cultural and creative industries in a seemingly casual but deeply coded manner. The literary festival presents the perfect opportunity for individuals to signal to those around them that they, for example, subscribe to the New Yorker or donate money to the V&A museum. This article presents the findings of an observational study conducted at four literary festivals in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Four distinct categories emerged from this analysis of tote bags carried at literary festivals: the festival tote that is sold at the festival; totes associated with cultural institutions; totes with political, satirical or ironic slogans; totes that are not associated with any particular arts or cultural brand or institution. I argue that, especially where the first three categories are concerned, the tote bags carried at literary festivals are consciously chosen for the purpose of signalling one’s cultural capital.

Keywords:

- Tote bags,

- cultural capital,

- literary festivals,

- conspicuous consumption,

- Bourdieu

Résumé

Le sac fourre-tout en toile, souvent marqué du nom et du logo d’une institution culturelle ou librairie populaires, est devenu un raccourci pour signifier le capital culturel accumulé par une personne. Par cet accessoire en apparence inoffensif, elle peut attirer l’attention de ses pairs sur le degré auquel elle souscrit aux industries culturelles et créatives, d’une manière qui se veut décontractée mais est en réalité profondément codée. Le festival littéraire constitue l’occasion idéale pour signaler aux autres qu’elle est une abonnée du New Yorker ou une donatrice du musée Victoria and Albert, par exemple. L’article présente les résultats d’une étude observationnelle menée dans quatre festivals littéraires en Australie, au Royaume-Uni et aux États-Unis. Quatre catégories distinctes se dégagent de cette analyse des sacs fourre-tout utilisés lors de ces festivals : le sac à l’effigie du festival vendu sur place; le sac associé à une institution culturelle; le sac portant un slogan politique, satirique ou ironique; et enfin, le sac qui n’est associé à aucune marque ou institution artistique ou culturelle particulières. Je soutiens que, particulièrement en ce qui concerne les trois premières catégories, le sac arboré lors de festivals littéraires est choisi de façon consciente, dans le but de rendre manifeste le capital culturel de celui ou celle qui le porte.

Mots-clés :

- Sacs fourre-tout,

- capital culturel,

- festivals littéraires,

- consommation ostentatoire,

- Bourdieu

Article body

Book fairs and literary festivals are performance spaces. All those who attend—featured authors, expert moderators, and book lovers alike—have the opportunity to enact their literary and cultural identities by signalling their accumulated cultural capital. This performance plays out in a number of ways, however, and the increasing ubiquity of the branded canvas tote bag has become, in many contexts, a synecdoche for one’s cultural and social class bona fides. A simple canvas tote bag that prominently displays the branding of a particular publisher or bookstore or gallery or museum can, especially when carried at events like a literary festival, denote a sense of literariness or even sophistication. Moreover, when observed en masse at a literary festival, these totes not only tell us about the collective cultural capital of the literary festival audience, but also the kinds of institutions that, in the eyes of the literary middlebrow, are considered prestigious and valuable. This article explores the notion of performing cultural capital and presents findings from research conducted at four literary festivals in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, proposing a new understanding of the intersection of cultural capital, class, taste, and cultural consumption.

To understand the role of the branded canvas tote bag within the context of the contemporary literary festival, it is first important to understand the audience who carry the totes. The profile of literary festival audiences has been the subject of rigorous engagement, both within and outside the academy, with varying observations offered about who attends literary festivals and their motivations for doing so. Where in the mainstream media and cultural press the audience can be the subject of mockery or disdain,[1] the scholarly examinations of these cultural events present a more nuanced understanding. One common observation in these analyses, both scholarly and not, is that women are highly represented in these spaces. Beth Driscoll’s examination of contemporary literary tastemaking practices unpacks the broader cultural assumptions and criticisms that surround the highly feminized literary festival audience, connecting mass media criticism of the audience to modernist constructions that conflate masculinity with literary value.[2] Driscoll goes on to note that in addition to the fact that literary festival audiences are predominantly women, the audience can also be described as one that displays a great enthusiasm for book culture and a “reverential treatment of elite literary authors.”[3] Millicent Weber extends our understanding of the literary festival audience, observing that attendees seek access to the particular cultural and social spaces within which festivals are located[4] and that individuals “professionally connected to the production and circulation of literature” are strongly represented within festival audiences.[5] Wenche Ommundsen neatly encapsulates both Driscoll’s and Weber’s observations, noting that the literary festival audience can be characterized as one that has a closer and perhaps more sophisticated relationship with literature than the general population.[6] These analyses demonstrate that, for a particular group of cultural producers and consumers, the literary festival is an important space that offers the opportunity to express one’s cultural capital within the context of celebrating the public life of literature. For this reason, the literary festival is fertile ground for the study of the tote bag as a product that denotes one’s cultural capital within contemporary literary culture.

A foundational characteristic of contemporary literary festivals is the tension between culture and commerce that sits at their core. And while this tension has, at times, left these events exposed to criticism from some authors and literary critics,[7] the culture-commerce connection is perhaps the reason that the events have remained viable and even grown in popularity over the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The relationship between the commercial nature and the literariness of literary festivals is an integral element in this research; I argue that the deployment of a consumer item—the tote bag—to signal an individual’s cultural capital is, in and of itself, an example of the relationship between culture and commerce that is not only necessary for the existence of the literary festival, but is also exemplary of the very nature of cultural engagement within and beyond the field of cultural production. The tote bag does not resolve the tension between culture and commerce that defines the contemporary publishing industry and the celebration of this industry in the form of the literary festival, rather, it is emblematic of this tension. Literary and cultural tote bags give us the opportunity to observe the interaction between culture and commerce as a mode of self-expression. In his study of class and taste, Pierre Bourdieu describes the ways in which the consumption and appreciation of particular cultural goods can denote membership of different social classes.[8] Cultural capital is established and maintained by a series of educative and socio-economic factors, as well as the consumption of certain cultural products. For this reason, beyond the tightly structured field of cultural production, it is the commercial relationships that individuals have with culture and cultural products—through festivals, cultural events, exhibitions, travel—that underpins their accumulated cultural capital. Where authors or literary critics may express disdain for the commercial nature of literary festivals, for the middlebrow reader their commercial nature presents the perfect opportunity for literary engagement and celebration.

Bringing together notions of cultural capital and consumption establishes a context in which we can examine the expression of one’s cultural capital in action, and understand the contemporary real‑world manifestations of this practice. In his exploration of the application of Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital in an American consumer context, Douglas B. Holt observes the fluid nature of cultural capital expression, noting “cultural capital exists only as it is articulated in particular institutional domains.”[9] Holt offers a helpful appropriation of Bourdieu’s theory of capital, allowing for a deeper understanding of the role that the tote bag, as a signifier of cultural capital, plays in the literary sphere and, more specifically, within the context of the literary festival. First, Holt acknowledges a vital part of the relationship between cultural capital and consumerism when he notes that the expression of cultural capital through consumer items is predicated on these items being “ideationally difficult” so that their semiotic status can only be “consumed by those who have acquired the ability to do so.”[10] If we consider this statement in light of Driscoll’s, Ommundsen’s, and Weber’s collective articulations of the contemporary literary festival audience—characterized as tertiary educated women with a deep reverence for and connection to literary culture—questions arise around the signifiers of cultural capital that could speak in a meaningful and aspirational way to fellow literary festival goers, such as the branded canvas tote bag.

Holt’s acknowledgement of the role of the “surrogate representations”[11] of cultural practice as an integral aspect of the identification and expression of cultural capital, particularly within specialized contexts such as literary festivals, demonstrates the ways in which tote bags often act as the “surrogate” or stand-in for one’s cultural capital. For example, carrying the Shakespeare and Company bookstore tote signals to a knowing audience that the carrier has visited the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris and suggests that the tote carrier’s foreign travels are punctuated by visits to historic literary sites that were once favoured by James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. Those who have “acquired”[12] an understanding of the perceived cultural significance of the Shakespeare and Company Bookstore, through education and/or cultural interactions, know that the symbolic reputation of the store and can acknowledge the tote carrier’s now-established connection to it. Holt would perhaps describe the literary festival audience as a group with the “cultural aptitude” necessary to interpret this cultural signal.[13] To those without the necessary cultural understanding, the bag is just a bag. In a similar vein, John Berger and Morgan Ward’s research into inconspicuous consumption suggests that individuals who have accumulated cultural capital in a specific field—for example, the literary field—are likely to partake in a form of inconspicuous consumption wherein they deploy logos and branding on clothing and accessories that signal their status to “others in the know,”[14] thereby elevating themselves from the mainstream.

The canvas tote bag—known in some contexts as a book bag—is a humble, practical, and deeply coded item of cultural paraphernalia. While not exclusively located within the literary domain, these bags are an essential and often light-heartedly ridiculed part of the circulation of literary culture. This gentle ribbing often plays out on social networking platforms, and demonstrates the field’s relationship to the tote bag. For example, author Emily Gould’s 2019 tweet that observed:

If I’ve learned anything from fifteen years in book publishing, it’s this: don’t hesitate to part with any of your totebags. New totebags will soon enter your life to replace them. The number of totebags remains constant, an eternal stasis.[15]

The cultural resonance of the tote bag has also caught the eye of cartoonist Ellis Rosen. Rosen’s illustration in the New Yorker’s satirical Daily Shout section depicts a “tote bag etiquette” noting that “Though tote bags are an excellent form of self-advertising, Tote Law states that your bag must reflect your actual interests,” and “Freshly baked bread quaintly sticking out of a tote must be longer than half of the carrier’s forearm.”[16] Gould’s tweet and Rosen’s cartoon are just two of many similar humorous meditations on the contemporary socio-cultural resonance of the branded canvas tote bag, and they illustrate the position that tote bags occupy within the literary cultural psyche, as products that are both essential and frivolous.

The rise of the branded canvas tote bag as an object situated within cultural sectors like the publishing industry is a relatively recent phenomenon. And while it is difficult to pinpoint the catalyst for their visibility among consumers, some commentators point to a desire to appear to be ecologically conscious as the primary foundation of the bag’s contemporary increasing popularity.[17] Global market research firm Technavio observed that the global tote bag market grew by 4.91 percent over 2019, and is set to increase by USD 5.74 billion between 2018 and 2023; they attribute this growth to increased global spending capacity and a desire for environmentally sustainable fashion choices.[18] However, it appears that this environmentally conscious consumption might be misguided. Research by both Denmark’s Ministry of Environment and Food and the UK’s Environment Agency explore the environmental impact of canvas and cotton tote bags, observing that cotton tote bags have a much higher environmental impact than paper, biopolymer and heavier reusable plastic bags; that cotton tote bags should would have to be re-used upwards to 131 times in order to justify their environmental impact; and that the global warming potential of cotton and canvas carrier bags is more than 10 times that of carrier bags made from other materials.[19] Moreover, the majority of cotton and canvas tote bags are produced in China or India,[20] meaning that the environmental impact of the totes sold in countries like the UK, Australia, and the United States is more significant than just the resource strain associated with manufacturing.

The branded canvas tote bag may appear to be an environmentally conscious consumer choice but in reality the decision to carry a branded canvas tote bag is an aesthetic and not an ecological one. Nevertheless, the popularity of these bags among audiences at cultural events such as literary festivals suggests that the tote-carriers are conscious that their choice of bag communicates particular values. The literary festival, as a space where many cultural consumers come together, is an ideal place for observing the different tote bags that people carry as they communicate, either consciously or subconsciously, their environmental and cultural capital.

Like the literary festival itself, the tote bag is representative of the capitalistic aspects of contemporary bookish practice. Despite their designation as frivolous, tote bags are routinely sold in independent bookstores, on publishers’ websites, at museums and galleries, and, importantly, at a number of literary festivals in the Anglophone field. The disciplines of marketing and consumer research are helpful for understanding the perceived importance of a para-cultural consumer product that is so deeply rooted within the cultural industries. These bags are not themselves cultural or art products, and neither are they the primary output of authors and publishers and galleries; rather, they are objects of marketing and promotional merchandise that, because of their connection with symbolically wealthy cultural outputs and institutions, have come to represent a connection between a given institution and the individual carrying the tote. Celia Lury’s articulation of the “brand as assemblage” offers helpful insights into the positionality of the tote bag within the literary field.[21] Lury encourages us to view a branded object as a “set of possible relations and connections”, rather than discrete, uncoded items[22], and emphasises that the reverence for a particular brand within a certain community is not simply a social construction, rather is rooted in the real-world production for which the brand is responsible.[23] Using the rhetoric of marketing and economics, Lury carefully unpacks the ties between a cultural brand, their artistic output, and the paraphernalia used to promote the brand and provide opportunities for assemblage, giving us the opportunity to consider the relationship between these ties and how cultural brands are co‑opted for the purpose of communicating one’s cultural capital.

Considering this relationship raises questions around how tote bags are used by literary festival attendees—both those who operate within and those who operate outside of the field of cultural production—to communicate their cultural capital to a knowing and receptive audience. Moreover, what can we learn about the kinds of cultural institutions that are so highly regarded in the estimations of literary festival attendees that they warrant the explicit public endorsement that comes with carrying a tote bag adorned with their branding? These were the questions that framed the observational study that I undertook at four literary festivals and book fairs in 2019. The results of this study suggest that, in line with Bourdieu’s, Lury’s, Holt’s, and Berger and Ward’s research, the inconspicuous consumption and public display of the branded tote bags that act as a surrogate for one’s accumulated cultural capital is a common practice at Anglophone literary festivals, and in many cases the difficulty associated with decoding the provenance of a tote bag is associated with elevated cultural capital. I argue that this is a largely conscious act of performance by the tote‑carrying literary festival attendees.

Method

I set out to explore these questions at a sample of Anglophone literary festivals and book fairs. The sample was established using a purposive/convenience method; conducting research at events of this scale is often dependent on a pre-determined literary calendar. I undertook participant observation at each of these events, a method that I chose as it allowed me to see, analyze, and understand the tote bags that festival goers were carrying, as I too was a festival goer carrying a tote bag. Through participant observation, I was able to take part in and analyze the “explicit and tacit aspects”[24] of the ways in which festival goers perform their cultural capital and “reveal meanings”[25] about the use of tote bags as cultural signals in this setting. Participant observation is a particularly pertinent methodological approach for a study of this nature because at its heart is the pursuit of new understandings built from the realities of both everyday and ritualistic practice.[26] This inductive approach has given me the opportunity to be guided by this cultural practice as I seek to articulate new understandings of cultural capital as performance.

I visited a variety of different kinds of festivals or fairs in Australia, the UK, and the US in order to observe festival attendees in various national contexts: Adelaide Writers’ Week (Writers’ Week) in March 2019, the Hay Festival in May-June 2019, the Printers Row Lit Fest (Printers Row) in Chicago in June 2019, and the Harlem Book Fair in July 2019. Prior to attending the first festival in the sample, Writers’ Week, I established an observation protocol that would be simple to execute in the field, and to replicate across the four festivals. The aims of this observation protocol were to record the different tote bags that I observed at each literary festival and to record my observations of the festival attendees and the festival more generally. To achieve these aims, I conducted the research in two phases; while at the festival site I would focus exclusively on recording the different tote bags, and immediately after I left the festival site I would record my more general observations.

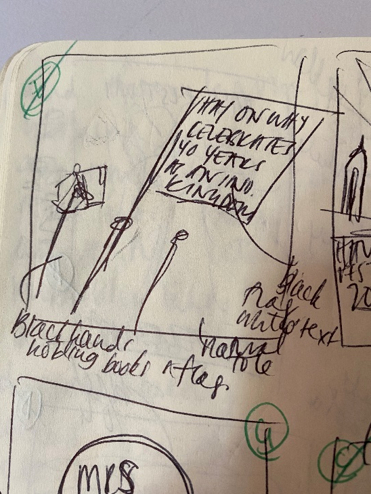

Figures 1-2

While I initially thought that photographing the totes with my mobile phone would be the most efficient and accurate approach to recording the various totes, I was concerned that photographing individuals’ tote bags without permission could be an invasion of their privacy and might make them anxious or suspicious. On the other hand, getting permission from every tote carrier I photographed would be prohibitively time-consuming. Being both flexible and detail-orientated is an important of the collection of accurate and reliable field data.[27] I felt that photographing fellow festival goers and their tote bags would problematize the participant side of participant observation and introduce unnecessary hurdles and ethical complexities to the project. Therefore, to record the totes carried at each festival, I prepared a number of pages in my notebook so that each tote I observed could be quickly sketched (see Figure 1). This approach proved fruitful as I was able to roughly sketch the tote bags that I saw without drawing too much attention to myself, and I could therefore observe and record a greater number of tote bags with more precise detail. The sketching process was rapid, and I aimed to record as much information about each tote bag as I could, such as the colour of the bag and the graphic, the logo, and the brand. This aim, together with my limited artistic abilities, meant that I did not concern myself with the aesthetic nature of the sketches (see Figures 2, 3, and 4). Sketching the tote bags in a notebook gave me the added benefit of being able to annotate the sketches with notes and observations, and divorced the tote bags from their carriers when it came to my analysis. The focus, therefore, was the bags themselves—with their often distinct branding—and not the individuals carrying them or what might be inside.

Figures 3-4

After spending the day sketching the tote bags, I would record my observations following a simple uniform protocol: portrait of attendees, the setting, my reactions. I aimed to record objective observations of the attendees and the festival setting. For example, when establishing the portrait of attendees and the setting of Writers’ Week, I noted that the majority of the attendees appeared to be white women and that the festival was set among a number of large trees in a city park and that the onsite bookstore was busy. When it came to my reactions, I allowed myself to move to more subjective interpretations, based on my observations. For example, at Adelaide Writers’ Week I observed that it appeared as though a number of the festival attendees go to the event year after year and that many of these attendees who continued to come back to the festival feel a sense of ownership over the event. The combination of the tote sketches and my objective and subjective reflections from the four events has established a rich database, one that facilitates the exploration of the central question in this research: what kind of tote bags do literary festival audiences use to perform their cultural capital-rich identities?

The Festivals

Established in 1960, Adelaide Writers’ Week is Australia’s longest running literary festival. The week of programmed lectures, one-on-one talks, and panel discussions operates within the larger institution of the Adelaide Festival, an annual three-week cultural and arts festival that runs in late February and early March. Writers’ Week is held in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden in Adelaide’s city centre and, unlike many similar festivals held in Australia, Writers’ Week is an entirely free event. Perhaps due to its long history and the attraction of the warm weather the southern hemisphere experiences in February and March, Writers’ Week has consistently attracted “big names” in fiction and non-fiction; for example the 1976 Writers’ Week hosted James Baldwin, Shirly Hazzard and Wole Soyinka. The 2019 event was similarly star-studded; highlights included Ben Orki, Oyinkan Braithwaite, Carolin Emcke, and Melissa Lucashenko. The programming of Writers’ Week is consistent with Driscoll’s articulation of the position these kinds of events occupy within the literary field; the programming of Booker Prize- and Miles Franklin Literary Award‑winning authors is “integral to the self-branding of literary festivals,” and there is an abundance of opportunities for the celebration of and “reverential treatment of elite literary authors.”[28]

I attended the Hay Festival in Hay-on-Wye in Wales on June 1 and 2, 2019. The first Hay Festival (then known as Hay Festival of Literature and Arts) took place in 1987 in a tent out the back of Kilverts Pub in the Welsh “town of books” Hay-on-Wye.[29] Similar to Writers’ Week in Adelaide, a number of high-profile guests in the early years of the festival quickly secured the festival’s position as an event for lovers of literature and reading; Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, and Stephen Hawking were among the speakers in the early days of the festival. Today the festival is a major part of the international literary calendar and the event has expanded to a number of satellite events across the globe: Mexico, Spain, Peru, Colombia, and Croatia. The Hay Festival offers both free and ticketed events, ranging from £5 to £40. What immediately struck me about the festival, especially in comparison to Writers’ Week, was the sheer scale of and the number of attendees at the event: the Festival’s sponsorship kit reports that in 2018 more than 270,000 tickets were sold.[30]

A major difference between Adelaide Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival is the explicit hierarchy that the Hay Festival establishes among various attendees and between attendees and speakers. And while the gap between the attendees and the speakers is a common feature of many arts and culture festivals, the structured divide between different attendees is less so. This hierarchy of attendees is rooted in the “Friend of Hay Festival” or “Hay Festival Patron” supporter program,[31] where for between £32 and £1000 a year, festival attendees receive a number of benefits including priority booking for festival events, the ability to skip the queue at each festival event, and “The knowledge that your support is helping us to deliver another amazing year at Hay.”[32] I highlight this “friends” and “patrons” program because in addition to these benefits, the Friends of Hay Festival are issued with a lanyard to wear at the festival so, presumably, they can easily access all their promised rewards. The effect, however, is a stark visual contrast between those who are “friends” of the festival and those who are not. I observed many festival attendees who appeared proud to be displaying their shiny “Friend of Hay Festival” lanyard around their necks, zipping past the rest of the festival goers towards the priority queue. The impression that I got from these brisk encounters with the “friends” was that while the “regular” attendees might have an appreciation for books and reading, the “friends” appeared to be keen to project a sense that they were more committed and more passionate about the literary arts, far beyond the ordinary festival goer. Similar to carrying a tote bag from the London bookstore Daunt Books, the “friends” lanyard is another way of performing cultural capital. Where the Daunt Books tote bag has the potential to communicate a connection to the literary arts through the public display of a symbol from a highly respected bookselling institution that is rich in cultural capital, the “friends” lanyard establishes a similar connection between the person wearing the lanyard and the festival. These kinds of hierarchies and displays of cultural power were non-existent at the festivals I visited in the US, where both festivals operated within very different structures from those of Adelaide Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival.

Printers Row Lit Fest is held in Chicago’s former bookmaking centre, known locally as Printers Row. Now in its 35th year, the literary festival is the largest free outdoor literary event of its kind in America’s Midwest, according to the festival’s website.[33] I attended Printers Row on June 8 and 9, 2019. Media reports from the festival indicate that approximately 100,000 attended the festival on Saturday June 8,[34] and over the weekend there were more than 100 authors speaking on panels and doing readings. Printers Row is part-book fair, part-literary festival that features a number of programmed events as well as two large Chicago city blocks occupied by vendors: publishers, booksellers of new and used titles, literary societies, and self-published authors. The structure of New York City’s Harlem Book Fair is similar to Printers Row, with a combination of programmed speakers and local publishing vendors. The Harlem Book Fair, held in July, is the largest African‑American book fair in the US and is “the nation’s flagship Black literary event.”[35] The prestige of this festival, like that of Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival, has been established over a number of years through the guest speakers; authors such as Maya Angelou, Cornel West, and Sonia Sanchez have attended and participated in panels, readings, and one-on-one discussions. Both Printers Row and Harlem had a more community-orientated or grassroots feel about them than Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival. However, while both the Printers Row and the Harlem Book Fair attendees appeared far less homogenous than those attending Adelaide Writers Week and Hay Festival, the common tie among all four festivals’ audiences is a proximity to and an interest in books and reading, and the associated cultural capital.

The Totes

Not all tote bags are created equal. A study of the use of tote bags as signifiers of accumulated cultural capital cannot overlook the ways in which the increasing ubiquity of the tote bag as a para‑cultural item is inherently hierarchical. The primary distinction that structures this hierarchy is the tote bags that are free versus the tote bags that one pays for. Among the “paid for” tote bags, there are countless opportunities to communicate one’s cultural capital in distinct and translatable ways—for example, carrying a Hugendubel tote bag[36] within a distinctly literary setting. Hugendubel, one of Germany’s largest bookstore chains, has a mysterious tote bag with no obvious branding, meaning that it is difficult to decipher for those who are uninitiated, making it a perfect signifier of inconspicuous consumption.[37] But for the discerning literary acolyte, a seemingly obscure tote bag purchased from a Berlin bookstore signals cultural capital associated with continental travel and German literary culture. Provenance, obscurity, and inconspicuousness are key traits among the totes one pays for that signify voluminous cultural capital.

Where the free tote bags are concerned, the reason that the tote is free is essential to its ability to communicate cultural capital. A tote that comes free with a magazine or newspaper subscription establishes a connection between the publication and the tote carrier, and communicates this relationship to causal observers. The most famous example of this is the New Yorker tote bag, which I will explore in much greater detail in the following section. However, when a tote is free because of a personal connection to an event or institution, the cultural resonance of that tote bag is linked to the cultural position of the event or institution and is far superior to a “paid for” tote from that same event or institution. Authors who speak at events are often gifted a tote bag and editors in publishing houses are known to use the publishing house’s tote at literary events. This practice establishes a divide between the audience who pay to attend festivals or other literary events, and those who work in the industry. The para-cultural significance of the free tote bag is compounded when issues of scarcity come into play. Perhaps the most famous free literary tote bag—famous because of the institution it is associated with and the difficulty obtaining one—is the Joan Didion tote from online literary magazine Literary Hub.[38] This is a simple canvas tote with a photograph of the author Joan Didion printed on it; however Joan Didion did not give Literary Hub permission to use this image for commercial purposes, so the magazine can only give the tote away for free. Literary Hub give the tote away at selected events, often held in New York City, and so being seen with a Joan Didion Literary Hub tote is not only a rare occurrence for a tote bag observer, but it also denotes a strong connection between the tote bag carrier and the New York literary community. The fact that the tote is not for sale only serves to reinforce its para-cultural power.

Four distinct categories of tote bags emerged from my analysis of the tote bags I sketched at the literary festivals: the tote bag specific to or sold at that event, for example the Adelaide Writers’ Week tote at Adelaide Writers Week; tote bags from cultural institutions such as galleries, museums, publishers, bookstores, and cultural publications; tote bags that featured a slogan or political statement, such as the “On Wednesdays we Smash the Patriarchy” tote observed at the Hay Festival; and a category I am calling “other brands,” which catches the branded totes that could not be classified as representing a cultural institution, such as a Patagonia tote or a tote from The Championships, Wimbledon. Analyzing the tote bags within the framework of these four categories provided both inward- and outward-facing insights. Analysis of the totes carried at the festivals aligns with the contemporary research into the literary festival by scholars such as Weber, Driscoll, and Ommundsen that describes the audience as a typically tertiary-educated, typically middle-class group with a keenly developed relationship to and appreciation of the literary arts. Moving outward, analysis of the tote bags and their use in the signalling of cultural capital indicated which cultural institutions are highly prized by this audience, helping to establish a hierarchy among institutions and consumers.

The Festival Tote

Three of the four festivals in this study’s sample had an official festival tote. These tote bags were, particularly in the case of Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival, the most commonly carried totes observed at the event (see Figure 5). Writers’ Week sold the 2019 Adelaide Writers’ Week tote for $15 from the on-site festival bookshop. The Hay Festival tote retailed for £7 and could be purchased at the on-site bookshop or the tent dedicated exclusively to Hay Festival merchandise, items such as t-shirts, pens, notebooks, and mugs. In contrast, the Printers Row Lit Fest tote bag was given out for free at the Cable Satellite Public Affairs Network’s (C-Span) truck—C-Span being a major sponsor of the event—and did not quite have the same level of material quality as its Australian or the British counterpart. It is important to note that all of these totes can only be acquired at the actual event.

Figures 5-6

Of all the tote bags that I observed at Writers’ Week, the Hay Festival, and Printers Row, the most commonly sighted was either the 2019 festival tote for that specific event or the festival tote from previous years. In my analysis I have considered those carrying the 2019 tote bag and those carrying the totes from previous years in two distinct sub-groups. While there are a number of similarities between these sub-groups, in one clear way they represent different motivations when it comes to the displaying of cultural capital through the carrying of the tote. Where the similarities between these groups are concerned, by carrying the festival tote (both current and historic), it could be argued that these individuals are communicating their reverence for the event by—in the cases of Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival—purchasing a tote bag and proudly carrying it around the festival site and, perhaps just as important, by carrying it to, from, and beyond the festival. For this group, making an explicit and visible connection between themselves and the specific literary festival appears to be an important part of the festival-going experience. When it comes to the group of festival attendees sporting the 2019 tote, a desire to make a financial contribution to the festival, an interest in telegraphing to those outside the festival that they attended the 2019 event, and a tradition of collecting the totes for each year they attend are perhaps the primary motivations for buying and carrying around the current festival tote bag. As an added bonus, these totes are the perfect vessel for carrying about the books you purchase at the on-site festival bookstore.

The motivations around communicating cultural capital often differ for those carrying festival totes from previous years and those carrying the tote from the current year (see Figure 6). Carrying a tote from a previous festival—I observed totes from as far back as 2012 at Writers’ Week and 2001 at the Hay Festival—signals to fellow festival goers a long-running relationship with the festival, and projects a sense of ownership over or perhaps a superior or more elevated relationship with the event and, by extension, with contemporary literary culture. This was most evident at Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival, where a large number of festival goers were carrying totes from previous years, totes that were often well-worn. The feeling I had when observing festival attendees carrying historic festival totes was that there was a desire to project the notion that they are the real lovers of the literary festival, the true literary festival audience. Catherine Strong and Samuel Whiting’s research into the cultural aesthetics of Melbourne’s live music venues can help to illuminate the motivations of audience members who carry the festival’s tote from previous years.[39] Writing about the common practice of music venues keeping old gig posters on the wall, Strong and Whiting observe that these posters “shape notions of musical place and space” and that they establish “a sense of the venues’ embeddedness in the collective memory and history of the musical past.”[40] I argue that carrying an old festival tote bag echoes this idea, and that this practice establishes the individual in question as someone who embodies and reflects the “notions of … place and space” within the literary field, while simultaneously aligning themselves with and paying homage to the “collective memory” and rich history of these events—a history that includes some of the western literary canon’s most revered authors.

Cultural Institutions

Carrying tote bags from other cultural institutions—other festivals, galleries and museums, publications and publishers—was common among the tote carries at all four literary festivals in the sample. I argue that this group differ from those carrying the festival tote bag inasmuch as they are concerned with signalling a more well-rounded cultural persona. These tote-carrying members of the literary festival audience are more than just book lovers; the tote bags they carry indicate that they are cultural omnivores: they visit galleries, they give money to the V&A Museum, they listen to NPR, they indulge in European cultural tourism, they shop at independent record stores, and they read the New Yorker. Observing the cultural institution tote bags at the literary festivals in Adelaide, Hay-on-Wye, Chicago, and New York suggests that sporting a tote bag from a cultural institution gives the carrier the opportunity to communicate a number of interests including but not limited to contemporary art, continental travel, left-leaning journalism, and magazines that publish socio‑cultural criticism. Unlike the “official” tote of each literary festival, these totes help to establish a more complex understanding of the literary festival audience.

Figures 7-8

Museums & Galleries

Carrying a tote bag from a museum or gallery gift shop gives individuals the opportunity to signal to those around them, especially those around them who have what Holt would describe as “the acquired ability,” to recognize the cultural capital associated with these institutions.[41] There is a two-way, mutually beneficial exchange between the tote carrier and the tote observer: both the carrier and the observer are able to demonstrate their accumulated acquired cultural capital by signalling and by recognizing the highly symbolic cultural institutions promoted on the bag. Moreover, these tote bags speak to the kinds of leisure activities that these audience members are interested in participating in—and interested in signalling to others that they participate in—both at home and abroad. Tote bags from the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Hungarian National Gallery, and the Ballarat International Foto Biennale were observed and recorded at Writers’ Week (see Figure 8). Among the many totes from museums or galleries noted at the Hay Festival were souvenirs from the V&A, the Hereford Museum Trust, the Royal Academy of Arts, MoMa and the Paris Museum. A V&A tote was also spotted at Printers Row in Chicago, along with totes from the Art Institute of Chicago and Milan’s Teatro Alla Scala. What became clear from observing these totes among the entire festival audience was not only the symbolically rich institutions represented but also the number of institutions from other countries. This adds a layer of complexity to the tote as a cultural signal, indicating that these tote carriers not only spend their leisure time in galleries and museums, but also they are able to afford international travel to indulge this pastime. Mike Robinson and Marina Novelli’s research into “niche tourism” suggests that some tourists and holiday-makers are keen to “differentiate and distinguish” themselves from the notion of mass tourism and that different kinds of tourist experiences, among them what the authors call “art” tourism, are centred on status seeking.[42] I argue that visiting MoMA or the V&A or the Teatro Alla Scala is a form of status differentiation associated with niche tourism, a practice that can extend beyond the holiday itself through the purchase and use of a keepsake such as a tote bag. Totes purchased at bookstores have a similar cultural resonance; totes from Shakespeare and Company in Paris, the Strand Bookstore in New York, Foyles and Daunt Books in London, and Books are Magic in Brooklyn (all observed in non-local contexts) communicate that for a number of literary festival attendees, shopping at local bookstores is something they value and something they want their peers to know that they value.

The New Yorker Tote

The media tote bag—that is, the tote bag that magazines and newspapers give to readers when they subscribe to their publication—is an increasingly common item in the crowded tote bag scene. GQ’s Chris Gayomali notes that Vogue, Architectural Digest, Monocle, the New York Times, the Paris Review, Bon Appetit, and Vanity Fair all have their own totes that accompany a subscription.[43] However, no tote is more valued, more coded, more culturally significant, or more visible in a literary festival crowd than the New Yorker tote. The New Yorker tote was the most commonly seen tote across Writers’ Week, the Hay Festival, and Printers Row (23 were observed across the three events), suggesting that the symbolic value of the magazine remains ubiquitous in the Anglophone literary field. In theory, the only way to obtain a New Yorker tote is to subscribe to the magazine, therefore it follows that everyone carrying a New Yorker tote bag is, in theory, a subscriber. Perhaps more than any other tote bag, the New Yorker tote acts as shorthand for a number of literary and cultural values and practices that go hand-in-hand with the idealized image of a New Yorker reader. The reality of the New Yorker tote bag perhaps only reinforces the pedestal upon which the publication resides. Reports from 2017 indicate that more than 500,000 bags had been distributed to subscribers of the magazine and that the magazine’s publisher, Condé Nast, was struggling to keep pace with subscriber demand, meaning that new subscribers often experienced lengthy delays in getting their totes.[44] And while the tote is supposed to be exclusively for subscribers to the publication—a convention perhaps established in order to ensure that carriers are assumed to be readers—consumers who seek to obtain the bag without subscribing to the magazine can do so, for the right price. New Yorker tote bags are listed on eBay and Etsy for between $30 and $100, a significantly higher price than the tote bag that comes free with a 12-issue subscription priced at $10. I argue that carrying the New Yorker tote is the quickest and widest-ranging way to communicate cultural capital to the literary festival audience; it is an internationally translatable symbol of cultural capital that is highly recognizable within the literary festival crowd.

Slogans and Non-cultural Brands

Separate from the tote bags from symbolically wealthy cultural institutions, bookstores, and magazines, there was a cohort of tote bag carriers who carried tote bags that featured slogans or political messages (see Figures 9 and 10). These bags were most common at the Hay Festival, but they were also observed at Writers’ Week and Printers Row. These totes communicate values beyond the cultural and the literary spheres and provide insights into the profile of the festival audience; it is thus perhaps more appropriate to view these bags as less about projecting an audience member’s accumulated cultural capital, and more about signalling their sense of identity or personality. The slogan totes at Writers’ Week were different from those at the Hay Festival and Printers Row and represented a cosier and more apolitical aesthetic; they featured phrases such as “books are the new black” and “there’s no friend as loyal as a book.” And while these kinds of totes were also observed at Hay and Printers Row—bags featuring quips such as “go away I’m writing” and “I like big books and I cannot lie”—the majority of slogan totes at Hay and Printers Row had a more activist or politically progressive message. At the Hay Festival, the “books are my bag” tote was commonplace (representing a campaign to support shopping at small and local retailers), along with totes condemning animal testing, promoting the dismantling of the patriarchy, and a number proclaiming support for an independent Wales and the “Independent Kingdom of Hay-on-Wye.” As one might expect, the Printers Row activist totes were more American, with a number of totes featuring “I dissent” (a reference to liberal Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg), “I cannot live without books” (a phrase attributed to Thomas Jefferson), and, in one case, “save our bees”—suggesting that the tote carrier was an environmental activist. These sloganed totes provide insights into the constructed identities of the literary festival audience and the ways in which these differ across national contexts. The political nature of the slogan tote bags at the Hay Festival and at Printers Row suggest that many festival attendees conceive of their own identities as politically liberal or progressive, and that they are perhaps keen for those around them to view them as such. It is not, however, political slogans alone that illuminate the extra-cultural values of the literary festival audience.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Tote bags that are associated with non-cultural brands—that is, brands that are not linked to cultural or creative industries—were also commonplace at Writers’ Week, the Hay Festival, and Printers Row. Especially where Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival were concerned, totes connected to boutique and independent food retailers were common: totes from Adelaide’s independent boutique grocery Mercato, the Adelaide Cellar Door Wine Festival, Waitrose, Booths Food and Wine Grocery, Hay-on-Wye’s Alex Gooch Artisan Baker, the Hay Deli, and Aga (the historic cast-iron oven manufacturer popular among those who can afford it) were all observed. And while these non‑cultural branded tote bags at Printers Row did not appear to have the same culinary affiliations, I would argue that they, too, fit within a common consumer identity. Patagonia and Wimbledon totes were seen among the audience. These brands align with the profiles of the literary festival audience articulated by Weber, Driscoll, and Ommundsen; both the literary festival audience and brands like Booths Food and Wine Grocery or Patagonia are targeted towards the leisure classes.[45] The tote bag is, in this instance, used as an envoy for many facets of high cultural capital, including one’s social class.[46]

Conclusions

Literary festivals are events that present researchers with the opportunity to observe bookish audiences that are typically made up of two kinds of readers: those who contribute professionally to the production and circulation of literary texts, and those who engage with the circulation of literary texts as part of their personal lives. Both groups come together at the literary festival in celebration of authors, books, and reading. In addition to this celebration, the festival establishes an environment wherein the festival audience has the opportunity to communicate their accumulated capital to those they consider their cultural and creative peers. My observations from literary festivals in three national contexts support the notion that the literary festival is a space for performing one’s cultural capital, where the use of seemingly frivolous yet deeply coded items like the branded canvas tote bag to facilitate this performance is commonplace. The analysis of the tote bags carried at literary festivals in Australia, the UK, and the US presented in this article draws upon a number of scholarly disciplines in order to fully articulate the complex para-cultural role that the tote bag plays within the field of cultural production as a signifier of symbolic and cultural capital, and of the often overlooked relationship between culture and commerce that defines contemporary literary practice. Using the tote bag as a subject of analysis, this research establishes a nuanced understanding of the connection between audiences and the festival itself, of the kinds of cultural institutions that audience use as a shorthand for their accumulated cultural capital, and of the ways in which the tote bag not only denotes a carrier’s cultural bona fides, but also their social class.

The literary festival audience is one that can be characterized both by its deep affection for literary culture and also by its close attachment to the festival itself. Where the leading research into festivals by Weber, Driscoll, and Ommundsen highlights the bookishness of the audience, rarely do they consider this attachment. The high quantity of festival tote bags from past events, especially at Writers’ Week and the Hay Festival, speaks to the relationship between these festivals and their audiences, and the sense of ownership many festival goers may feel over the event. In contrast to those who carry the festival tote, audience members who carry totes from other cultural institutions—such as galleries, magazines, bookstores, and museums—are perhaps more concerned with projecting a sense of their own cultural capital as it exists beyond the confines of the literary festival. I argue that this example of inconspicuous consumption creates a two-way exchange among audience members “in the know” and can tell us which institutions are most highly prized by festival goers: the New Yorker, the V&A Museum, the Shakespeare and Company bookstore, and Daunt Books among them. Tote bags from cultural institutions, and in particular cultural institutions abroad, have the added benefit of communicating to one’s literary festival peers the socio-economic realities of one’s recreation; not only do these totes signal assumed cultural capital, but acquiring them is commonly accompanied by foreign travel.

Throughout this article I have often described the canvas tote bag as a deeply coded or symbolic accessory. However, it is important to articulate that this coding is not a feature inherent in the bag itself, but rather it is something that we, the tote bag carriers, have vested in the objects. The bag itself is not rich in cultural capital, the bag is elevated as an object of desire both within and beyond the field of cultural production through our collective belief in the cultural significance of that institution, and our eagerness to signal our complex creative and cultural identities to our communities. The literary festival as a microcosm of the literary field illuminates this broad cultural practice, highlighting the performative nature of how we present ourselves in our cultural interactions.

Appendices

Biographical note

Alexandra Dane researches contemporary book cultures, focussing on the relationship between gender, literary consecration and the power of formal and informal literary networks.

Notes

-

[1]

Wenche Ommundsen, “Literary Festivals and Cultural Consumption,” Australian Literary Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): 22; Millicent Weber, “At the Intersection of Writers Festivals and Literary Communities,” Overland September 6, 2017, https://overland.org.au/2017/09/at-the-intersection-of-writers-festival-and-literary-communities/.

-

[2]

Beth Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century (New York, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014), 29.

-

[3]

Ibid., 59.

-

[4]

Millicent Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture (New York, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018), 97.

-

[5]

Ibid., 79.

-

[6]

Ommundsen, “Literary Festivals and Cultural Consumption,” 30.

-

[7]

Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow, 155.

-

[8]

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Oxford: Routledge, 1984), 94.

-

[9]

Douglas B. Holt, “Does Cultural Capital Structure American Consumption?” Journal of Consumer Research 25, no. 1 (1998): 4.

-

[10]

Ibid.

-

[11]

Ibid., 5.

-

[12]

Ibid.

-

[13]

Ibid.

-

[14]

John Berger and Morgan Ward, “Subtle Signs of Inconspicuous Consumption,” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (2010): 556.

-

[15]

Emily Gould (@EmilyGould), “If I’ve learned anything…,” Twitter, January 9, 2019, https://twitter.com/EmilyGould/status/1082661011742752768

-

[16]

Ellis Rosen, “Tote Bag Culture Etiquette,” New Yorker, January 7, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/humor/daily-shouts/tote-bag-culture-etiquette.

-

[17]

Louise Benson, “Totes Awesome? The Rise and Rise of the Art and Design Tote Bag,” Elephant, June 12, 2019, https://elephant.art/totes-awesome-rise-rise-art-design-tote-bag/.

-

[18]

Technavio, Global Tote Bags Market 2019–2023 (2019), https://www.technavio.com/report/global-tote-bags-market-industry-analysis?utm_source=t9&utm_medium=bw_wk17&utm_campaign=businesswire.

-

[19]

Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark, “Life Cycle Assessment of Grocery Carrier Bags,” A Report for the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (2018), https://www2.mst.dk/Udgiv/publications/2018/02/978-87-93614-73-4.pdf, 72; Chris Edwards, “Life Cycle Assessment of Supermarket Carrier Bags: A Review of the Bags Available in 2006,” A report for the Environment Agency (2006), Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/291023/scho0711buan-e-e.pdf, 33, 43.

-

[20]

Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark, “Life Cycle Assessment,” 72; Edwards, “Life Cycle Assessment,” 24.

-

[21]

Celia Lury, “Brand as Assemblage: Assembling Culture,” Journal of Cultural Economy 2, no. 1–2 (2009): 67–82.

-

[22]

Ibid., 68.

-

[23]

Ibid., 77.

-

[24]

Kathleen Musante (DeWalt) and Billie R DeWalt, Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers (Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, 2010), 12.

-

[25]

Danny L Jorgensen, The Methodology of Participant Observation (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011), 4.

-

[26]

Ibid., 7.

-

[27]

Musante (DeWalt) and DeWalt, Participant Observation, 78.

-

[28]

Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow, 159.

-

[29]

“Everything You Need to Know About the 2017 Hay Festival,” BBC, 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/25fDmhSDpmNxyWqnTPggJ8s/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-2017-hay-festival.

-

[30]

Hay Festival Sponsorship. 2019, https://www.hayfestival.com/wales/sponsorship.

-

[31]

Hay Festival Friends, 2019, https://www.hayfestival.com/wales/friends

-

[32]

Ibid.

-

[33]

Printers Row Lit Fest, 2019, https://printersrowlitfest.org/.

-

[34]

“Printers Row Lit Fest Brings Out More Than 100,000 People In First Day,” CBS Chicago, June 8, 2019, https://chicago.cbslocal.com/2019/06/08/printers-row-lit-fest-brings-out-more-than-100000-people-in-first-day/.

-

[35]

Harlem Book Fair, 2019, https://www.harlembookfair.com/about-us.

-

[36]

Mikaella Clements, “Unpacking Berlin’s Mysterious Ubiquitous Tote Bag,” New York Times, September 3, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/03/style/berlin-tote-hugendubel.html.

-

[37]

Berger and Ward, “Subtle Signs of Inconspicuous Consumption,” 556.

-

[38]

Jessie Gaynor, “‘Why Can’t I Buy a Joan Didion Tote?’ And More Questions from the Expanded Lit Hub Universe Answered,” Literary Hub, December 18, 2019, https://lithub.com/why-cant-i-buy-a-joan-didion-tote-and-more-questions-from-the-expanded-lit-hub-universe-answered/.

-

[39]

Catherine Strong and Samuel Whiting, “‘We Love the Bands and We Want to Keep the on the Walls’: Gig Posters as Heritage-as-Praxis in Music Venues,” Continuum 32, no. 2 (2017): 151–61.

-

[40]

Ibid., 152.

-

[41]

Holt, “Does Cultural Capital Structure American Consumption?”, 5.

-

[42]

Mike Robinson and Marina Novelli, “Niche Tourism: An Introduction,” in Niche Tourism, ed. Marina Novelli (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2005), 5.

-

[43]

Chris Gayomali, “The Best Media Tote Bags, Ranked,” GQ, May 31, 2019, https://www.gq.com/story/best-media-totes.

-

[44]

Leslie Albrecht, “How a Free Canvas Tote Became a Bigger Status Symbol than a $10,000 Hermes Bag,” Market Watch, September 9, 2017, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/how-a-free-canvas-tote-became-a-bigger-status-symbol-than-a-10000-hermes-bag-2017-09-01.

-

[45]

Thorsten Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, edited with an introduction by Martha Banta (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 34.

-

[46]

Bourdieu, Distinction, 94.

Bibliography

- Albrecht, Leslie. “How a Free Canvas Tote Became a Bigger Status Symbol than a $10,000 Hermes Bag.” Market Watch, September 9, 2017. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/how-a-free-canvas-tote-became-a-bigger-status-symbol-than-a-10000-hermes-bag-2017-09-01.

- Benson, Louise. “Totes Awesome? The Rise and Rise of the Art and Design Tote Bag.” Elephant, June 12, 2019. https://elephant.art/totes-awesome-rise-rise-art-design-tote-bag/.

- Berger, John, and Morgan Ward. “Subtle Signs of Inconspicuous Consumption” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (2010): 555–69.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Oxford: Routledge, 1984.

- Clements, Mikaella. “Unpacking Berlin’s Mysterious Ubiquitous Tote Bag.” New York Times, September 3, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/03/style/berlin-tote-hugendubel.html.

- Driscoll, Beth. The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century. New York, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014.

- Edwards, Chris. “Life Cycle Assessment of Supermarket Carrier Bags: A Review of the Bags Available in 2006.” A report for the Environment Agency, UK, 2006. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/291023/scho0711buan-e-e.pdf.

- Everything You Need to Know About the 2017 Hay Festival. BBC, 2017. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/25fDmhSDpmNxyWqnTPggJ8s/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-2017-hay-festival.

- Gaynor, Jessie. “‘Why Can’t I Buy a Joan Didion Tote?’ And More Questions from the Expanded Lit Hub Universe Answered.” Literary Hub, December 18, 2019. https://lithub.com/why-cant-i-buy-a-joan-didion-tote-and-more-questions-from-the-expanded-lit-hub-universe-answered/.

- Gayomali, Chris. “The Best Media Tote Bags, Ranked.” GQ, May 31, 2019. https://www.gq.com/story/best-media-totes.

- Gould, Emily (@EmilyGould). “If I’ve learned anything….” Twitter, January 9, 2019. https://twitter.com/EmilyGould/status/1082661011742752768.

- Harlem Book Fair. 2019. https://www.harlembookfair.com/about-us.

- Hay Festival Friends. 2019. https://www.hayfestival.com/wales/friends.

- Hay Festival Sponsorship. 2019. https://www.hayfestival.com/wales/sponsorship.

- Holt, Douglas B. “Does Cultural Capital Structure American Consumption?” Journal of Consumer Research 25, no. 1 (1998): 1–25.

- Jorgensen, Danny L. The Methodology of Participant Observation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2011.

- Lury, Celia. “Brand as Assemblage: Assembling Culture.” Journal of Cultural Economy 2, no. 1–2 (2009): 67–82.

- Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. “Life Cycle Assessment of Grocery Carrier Bags.” A Report for the Danish Environmental Protection Agency, 2018. https://www2.mst.dk/Udgiv/publications/2018/02/978-87-93614-73-4.pdf.

- Musante (DeWalt), Kathleen, and Billie R. DeWalt. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, 2010.

- Ommundsen, Wenche. “Literary Festivals and Cultural Consumption.” Australian Literary Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): 19–34.

- Printers Row Lit Fest, 2019. https://printersrowlitfest.org/.

- “Printers Row Lit Fest Brings Out More Than 100,000 People In First Day.” CBS Chicago, June 8, 2019. https://chicago.cbslocal.com/2019/06/08/printers-row-lit-fest-brings-out-more-than-100000-people-in-first-day/.

- Robinson, Mike, and Marina Novelli. “Niche Tourism: An Introduction,” in Niche Tourism, ed. Marina Novelli, 1–10. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2005.

- Rosen, Ellis. “Tote Bag Culture Etiquette.” New Yorker, January 7, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/humor/daily-shouts/tote-bag-culture-etiquette.

- Strong, Catherine, and Samuel Whiting. “‘We Love the Bands and We Want to Keep the on the Walls’: Gig Posters as Heritage-as-Praxis in Music Venues.” Continuum 32, no. 2 (2017): 151–61.

- Technavio. “Global Tote Bags Market 2019–2023.” 2019. https://www.technavio.com/report/global-tote-bags-market-industry-analysis?tnplus.

- Veblen, Thorsten. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, edited with an introduction by Martha Banta. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Weber, Millicent. “At the Intersection of Writers Festivals and Literary Communities.” Overland, September 6, 2017. https://overland.org.au/2017/09/at-the-intersection-of-writers-festival-and-literary-communities/.

- Weber, Millicent. Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture. New York, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018.

List of figures

Figures 1-2

Figures 3-4

Figures 5-6

Figures 7-8

Figure 9

Figure 10