Abstracts

Abstract

Although he is the exemplar of poetic balance, control, and precision, Pope’s classical aesthetics and ecological vision are ultimately authorized not by restraint but by excess, by a response of wonder: emotive not rational, imaginative not formulaic, and fundamentally religious in nature. Pope’s lifelong and profound engagement with wonder—in both personal expression and formal poetics—embodies the tensions of his time: between myth and parody, enthusiasm and restraint, hyperbolic parody and interrupted awe, self-realization and self-loss, emotive expression and formalistic control. His poetry continually evokes the response of wonder, pushing at the boundaries of verse satire, and embodied through his mastery of the couplet. Wonder in Pope’s writings is specifically associated with admiration for the supranatural, with release from the limitations of the body, and with a sweeping environmental vision. Finally, the ideas of “stupefaction” and “rapture” appear throughout Pope’s work in a paradoxical expansion and distancing of perspective, with the perpetual fear of the loss of the observing self.

Article body

One of the commonplaces of Augustan classicism is the dictum nil admirari. Literally meaning “be astonished at nothing,” denoting a philosophic readiness and balanced moderation in the art of living,[1] the phrase became popularly associated with the label “Age of Reason” for the eighteenth century, and with its reputed dominance by satirical, political, and didactic verse. While Alexander Pope is English literature’s most famous exemplar of the balance, control, and precision of classical poetics, not to mention a self-proclaimed model of Horatian moderation, his classical aesthetics and, indeed, his cosmic ecological vision are ultimately authorized not by restraint but by excess, by a response of wonder: emotive not rational, imaginative not formulaic, and fundamentally religious in nature.

Pope’s engagement with the non-rational has been examined in seminal full-length studies by Rebecca Ferguson and David Fairer,[2] which help to locate him in the changing critical environment of the late seventeenth century, as rhetorical and poetic theory linked formalism to aesthetics, shifting from classical notions of poetic inspiration as a neo-Platonic criterion of absolute value to an emphasis on affective reader response. As Ferguson points out, citing Peter Dixon, the term “admiration” changed in connotation during this period “from the pejorative ‘stupefaction’ to ‘rational approbation,’” i.e. something like its modern meaning.[3] Moreover, even stupefaction, hitherto a term used to describe the effect of powerful writing on the ignorant and simple, gained credibility as the appropriate response to that which challenges human understanding, and as a marker of both moral and aesthetic intelligence. In this sense wonder was a feature of both classical tradition, in which it was seen as key to the operation of the sublime in artistic expression,[4] and of the emergent modern response—arising from both scientific and religious empiricism—to a radically expanded cosmos revealed through Newtonian science.[5] In literature, rhetorical and poetic manuals highlighted the qualities of “genius” and “fire”;[6] the term invention started to move away from its Latinate sense of finding rhetorical tools in an existing catalogue to that of inspired creative power, a shift notably evident in Pope’s own use of the term in his preface to his translation of Homer. The term imagination is also in transition at this time, moving away from pejorative associations with sin and delusion towards denoting a faculty combining the powers of enlightened perception and artistic creation.[7] This union of poetic feeling and reader response, first outlined by John Dennis in his Advancement and Reformation of Modern Poetry (1701), was linked with the faculty of imagination through a Lockean theory of vision combining image-making and the function of the eye, a theory memorably outlined for the public by Joseph Addison’s Spectator essays of 1712.[8]

The late seventeenth-century invocation of the response of wonder was thus a dynamic process replete with ambivalence, a characteristic that continues to inform even current criticism on Longinian aesthetics. Often described as “rapture” or a loss of a sense of self, in an overwhelming emotive response to objects that go beyond the limits of perception, this immersion of the self in the otherness of the perceived arose, ironically, from a new focus on the self: from philosophical, religious, and scientific empiricism, and an unprecedented recognition of the empirical validity of the subjective response. As an aesthetic and philosophical concept, wonder develops through an ongoing tension with the formalistic rhetorical tradition of artful persuasion. This particular ambivalence is clearly evident in the classical treatise frequently invoked, Longinus’s Peri Hupsos[9]—usually referred to as On the Sublime—which opens with a lucid analysis of the relationship between rhetorical strategy and emotive expression, clearly delineating the difference between persuasion and the action of the “sublime”:

For great and lofty Thoughts do not so truly perswade, as charm and throw us into a Rapture. They form in us a kind of Admiration made up of Extasy and Surprize, which is quite different from that motion of the Soul, by which we are pleas’d, or perswaded. Perswasion has only that power over us, which we will give it; but Sublime carries in it such a noble Vigour, such a resistless Strength, which ravishes away the hearer’s Soul against his consent.

An Essay upon the Sublime, 3

The chief feature of the response of wonder or “admiration” is ecstasy, or separation from the body, here described as separation from the willed consciousness of the self, acting “against his [the hearer’s] consent” and imaged as the near-violent overcoming of the will and reason. This is opposed to rhetorical persuasion, in which the hearer is an active participant who willingly “allows” the argument to have emotional power as well as logical validity. (Note that Longinus also invokes the traditional meaning of nil admirari, the association of admiration with “surprise.”) The rapture of the soul, or sense of a loss of self, through being immersed in that which is greater than oneself, is a distinguishing feature of the sublime, as is the word “resistless,” itself a favourite term of Pope’s, used repeatedly in this 1698 translation to characterize the action of the sublime in both individual perception and rhetorical technique.

In language later picked up by Pope’s contemporaries, notably Dennis and Addison, Longinus justifies the response of wonder through a religious basis, in both its effects on human nature—“it raises up the Soul to an exalted pitch … and makes it to conceive an higher Idea of it self” (An Essay upon the Sublime, 13)—and in the larger design of the universe:

[Nature] has inspir’d into our souls resistless love for every thing, which appears great and divine; so that the whole circle of the World is not wide enough for our boundless thoughts, and unconfin’d speculations. Our ambitious fancies range farther than the flaming limits of the Heavens, and the most distant prospects of the Universe.

An Essay upon the Sublime, 74

The justification for the emotion of wonder in the providential framing of human nature—here in Lucretian phrasing that will be echoed negatively in Pope’s Essay on Man[10]—will be repeated and popularized by Addison in his Spectator essays on the faculty of imagination. In these contemporary representations, the response of wonder (rapture, stupefaction, admiration) is not seen as the reaction of an ignorant and simple listener to the strategies of a clever speaker (a power dynamic still assumed in post-structuralist readings of Longinus)[11] but as the appropriate response to that which is beyond human imagining.[12] The scale and nuances of the affective responses should be noted as well: they range from awestruck stupefaction, bordering even on the dulling of the senses, to the rational approbation increasingly linked to the term admiration. Longinus’s treatise was widely reproduced in both original annotated versions and various translations through the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (see footnote 9 above); as a text it embodies many of the common elements of contemporary poetic theory, all rooted in the notion of the sublime, as applied to both emotive experience and classical authority. These themes will be familiar from Pope’s Essay on Criticism: the universality of appeal across diverse readership; the quasi-divine authority embodied in great writers (Homer being cited most frequently), raising them up “to be a kind of a God”; the superiority of sublime writing to minor faults, in the fact that “Great Wits may sometimes gloriously offend”:[13]

Excellence in any other part of a Discourse, shews the writer to be advanc’d only to the highest standard of Humanity; but Sublime raises him up, till it has exalted him to be a kind of a God. To be without faults, makes an Author no other than unblameable, but Sublime renders him the object of universal wonder…. These extraordinary writers often times by one noble beauty, one sublime flight, attone for all their faults.

An Essay upon the Sublime, 77

Throughout this short treatise, Longinus elides rhetorical techniques and artistry with the experience of both the orator/writer and that of the listener, so that sublimity is both a conscious strategy and a perceived experience.

The most detailed contemporary analysis of reader response as a basis for poetic theory, with some debt to Longinian ideas of the religious sublime, is provided by Dennis in the aforementioned Advancement and Reformation of Modern Poetry. In Dennis’s interpretation, poetry is defined by passion (“Passion then is the Characteristical mark of Poetry, and consequently must be every where”[14]); like Longinus, he distinguishes between regular or controllable emotion and the characteristic of sublimity, which elicits an involuntary response, in his view belonging to religious subjects: “I call that ordinary Passion, whose cause is clearly comprehended by him who feels it, whether it be Admiration, Terror or Joy; and I call the very same Passions Enthusiasms, when their cause is not clearly comprehended by him who feels them.”[15] These emotions are not simply produced by rhetorical techniques to elicit passion in the reader, but arise expressively, from the passion felt by the poet:

And what is it but the expression of the passions he [Virgil] felt, that moves the Reader in such an extraordinary manner…. And thus we have endeavour’d to shew how the Enthusiasm proceeds from the thoughts, and consequently from the subject. But one thing we have omitted, that as thoughts produce the spirit, the spirit produces and makes the expression.[16]

Finally, Addison’s analysis of the faculty of imagination, which provides a detailed commentary on wonder as both faculty and experience, was produced early in 1712 for the popular reading public in The Spectators 411–21.[17] While the relation of these essays to Lockean epistemology, Coleridgean theories of fancy and imagination, and Burke’s aesthetics has been well recognized, in these passages Addison also provides one of the most detailed and popular distillations of the rationale for the emotion of wonder, or the rationalizing of the non-rational:

Our Imagination loves to be filled with an Object, or to grasp at any thing that is too big for its Capacity. We are flung into a pleasing Astonishment at such unbounded Views, and feel a delightful Stillness and Amazement in the Soul at the Apprehension of them. The Mind of Man naturally hates every thing that looks like a Restraint upon it, and is apt to fancy it self under a sort of Confinement, when the Sight is pent up in a narrow Compass, and shortned on every side by the Neighbourhood of Walls or Mountains. On the contrary, a spacious Horison is an Image of Liberty, where the Eye has Room to range abroad, to expatiate at large on the Immensity of its Views, and to lose it self amidst the Variety of Objects that offer themselves to its Observation. Such wide and undetermined Prospects are as pleasing to the Fancy, as the Speculations of Eternity or Infinitude are to the Understanding.[18]

One of the Final Causes of our Delight, in any thing that is great, may be this. The Supreme Author of our Being has so formed the Soul of Man, that nothing but himself can be its last, adequate, and proper Happiness. Because, therefore, a great Part of our Happiness must arise from the Contemplation of his Being, that he might give our Souls a just Relish of such a Contemplation, he has made them naturally delight in the Apprehension of what is Great or Unlimited. Our Admiration, which is a very pleasing Motion of the Mind, immediately rises at the Consideration of any Object that takes up a great deal of room in the Fancy, and, by consequence, will improve into the highest pitch of Astonishment and Devotion when we contemplate his Nature, that is neither circumscribed by Time nor Place, nor to be comprehended by the largest Capacity of a Created Being.[19]

Here admiration is seen as pleasurable, but pleasure is not a moral weakness, rather it is a natural expression of the higher self: “pleasing Astonishment,” “delightful Stillness and Amazement,” and “Astonishment and Devotion” are the appropriate responses to the nature of God, and are reflected in an innate human attraction to the unbounded, immense, and undetermined, specifically in the natural world. This is an imperative of human nature, even at the risk of the loss of self, or submersion of the seer in thing seen, where the perceiving eye can “lose it self” amidst an unbounded variety of objects of observation. While Addison notably elides the terms fancy and imagination, he also links fancy with “Understanding” rather than opposing these terms: “Such wide and undetermined Prospects are as pleasing to the Fancy, as the Speculations of Eternity or Infinitude are to the Understanding.” He thus elides physical and imaginative observation, blurring them with the conceptual and metaphysical. The language of wonder is combined with Lockean philosophy to create a theory of vision in both the physical and non-physical (spiritual) senses; the imagination is the central faculty of perception as well as expression, and thus it is also key to the human relationship to otherness. In a memorable passage, Addison later suggests through the Lockean faculty model that all physical vision seen through secondary qualities of light and colour, created by the eye and the brain, is like the delusory world of fantasy, which dissolves to leave a bleak landscape;[20] yet as this is the world as perceived by all his readers, this image itself breaks down the binary between fiction and fact, fantasy and objective reality.

Pope’s lifelong and profound engagement with wonder—in both personal expression and formal poetics—embodies the tensions of his time: between myth and parody, enthusiasm and restraint, hyperbolic parody and interrupted awe, self-realization and self-loss, emotive expression and formalistic control. Ultimately, however, his poetry conveys a sense of pressing fulness, of the supra-natural and apocalyptic, pushing at the boundaries of verse satire, and embodied through his mastery of the couplet. Wonder in Pope’s writings is specifically associated with admiration for the supranatural, with release from the limitations of the body, and with a sweeping environmental vision. Pope’s articulation of the response of wonder arises from the notions of literary, cultural, and religious authority that form the basis for both his satires and didactic writings. At the same time, in a phenomenon powerfully evident in Pope’s work and as yet not adequately considered, wonder reflects a felt sense of the otherness of the universe, not only of the sweeping Newtonian cosmos but also of nonhuman nature and the natural environment. Pope thus participates in the contemporary responses of wonder, both theological and aesthetic. His expressions of sublimity, however, often take the form of an attack on anthropocentricism based on his relational concept of the environment, seen for example in the apocalyptic imagery of the divinely-infused natural world in An Essay on Man, and in its parodic inversion in The Dunciad. Pope’s particular brand of fideistic skepticism thus ironically generates the response of wonder, of overpowering fulness pushing the limits of rhetorical hyperbole into the realm of the inexpressive.[21] At the same time, for Pope, the response of wonder is specifically associated with freedom from the limitations of the body, in his particular and personal application of Longinian ecstasis. Finally, the ideas of “stupefaction” and “rapture” linked to a loss of will and sense of self in Longinus appear throughout Pope’s work in a paradoxical expansion and distancing of perspective, with the perpetual fear of the loss of the observing self.

Early in his career, well before his megaproject, the translation of the Iliad and Odyssey, Pope writes of his experience of reading Homer to his friend Ralph Bridges, describing “that Rapture and Fire, which carries you away with him, with that wonderfull Force, that no man who has a true Poetical spirit is Master of himself, while he reads him.”[22] Pope’s long engagement with Homer translation may run the gamut of rationalistic wit as he recounts his struggles in letters, but it is the response of wonder that becomes the backbone of his poetic theory in the preface to his translation of the Greek poet’s masterpieces, as he echoes the same sentence—“It is to the Strength of this amazing Invention we are to attribute that unequal’d Fire and Rapture, which is so forcible in Homer, that no Man of a true Poetical Spirit is Master of himself while he reads him.”[23] This passage goes on to describe the force of Homer’s poetic imagination in elemental, global, and cosmic terms, sweeping away formalist critique to focus on the response of the reader:

The Course of his Verses resembles that of the Army he describes…. They pour along like a Fire that sweeps the whole Earth before it…. Exact Disposition, just Thought, correct Elocution, polish’d Numbers, may have been found in a thousand; but this Poetical Fire, this Vivida vis animi, in a very Few. Even in Works where all those are imperfect or neglected, this can over-power Criticism, and make us admire even while we disapprove…. [W]here this appears, tho’ attended with Absurdities, it brightens all the Rubbish about it, ‘till we see nothing but its own Splendour…. This strong and ruling Faculty was like a powerful Star [Planet 1715], which, in the Violence of its Course, drew all things within its Vortex.

Preface to Homer, 4–5

While many of these ideas—Homer’s creative genius, elemental energy, and superiority to formal restrictions—have some basis in Longinian tradition, this passage also outlines the basis for Pope’s aesthetics of wonder. As David Fairer aptly points out, Pope’s imagery of the “Vortex” to describe the power of Homer’s “ruling Faculty” of creative invention ironically parallels the description of the power of Dulness: both “are figures of universal power who draw everything into themselves—the supreme poet of imagination, and the tyrannous queen of fantasy and illusion.”[24] Fairer sees this relation as exemplifying in Pope’s writings the tension between passion (imaginative sympathy) and formal control;[25] what should also be noted here is the allusion to the Newtonian universe, imaging Homer’s creative force as a speeding planet, alongside the Greek poet’s own metaphor for violent conquest, thus capturing the essential violence of the sublime action and reaction, across time as well as across widely divergent conceptual spheres. While recalling Addison’s loss of the observing self in the immersion of experience, the loss of self-“mastery” celebrated here is peculiarly specific in invoking the language of embodiment and self-control, both affirming and denying the concept of “mastery” (control, art, and authority) in the response of involuntary wonder. Like Longinus, Pope also elides reader with creator in this process, linking poet with reader in the “true Poetical Spirit” required for experiencing the sublimity of Homer’s writing, in a model that reflects the newer response-based aesthetic, but that also applies classical ideas of inspiration to the act of reading as well as that of writing.[26] In his characteristic qualification, by which we “admire even while we dis-approve” Homer’s “Absurdities,” Pope invokes the Horatian duality expressed in An Essay on Criticism (“Fools admire, but Men of Sense approve”),[27] but he gives men of sense the right to “admire”—based on non-rational or even supra-rational forces such as a “true Poetical Spirit.”

Pope applies Aristotle’s authority to assert that all poetry has “fable” at its core: having taken in all Nature (the visible world and human nature) by his imagination, and “wanting yet an ampler Sphere to expatiate in,” Homer “open’d a new and boundless Walk for his Imagination, and created a World for himself in the Invention of Fable. That which Aristotle calls the Soul of Poetry, was first breath’d into it by Homer” (Preface to Homer, 5). Here Pope plays on a range of classical and contemporary associations: the Aristotelian Greek term for plot or story; and the notion of fantasy, stories of imagined worlds, referred to by both Addison and Dennis as aspects of the imaginative sublime. Pope links fable to the infinitude of divinely-ordained perception, described in both Longinus and Addison, and specifically applied to Homer by the former (“the fancy of Homer, which is unconfin’d and boundless” [An Essay upon the Sublime, 18]).

This passage is notable for Pope’s characteristic use of the term “expatiate,” to denote, not speaking at length on a topic, but rather, walking freely in realms of imagination, unencumbered by material (or bodily) limitations. In one of his winter letters, for example, Pope describes his body as cowering by a fire, while his mind is “expatiating in an open sunshine”[28]; the ambiguity of the term will be exploited precisely in the exordium to An Essay on Man twenty years later, as the poet invites his Horatian adversarius Bolingbroke to “expatiate free o’er all this scene of Man,”[29] in a line that suggests empirical ties to realism while resting on a premise of untrammelled imagination. In a recent article, Robert A. Erickson expands on the notion of separation from the body, ecstasis, or rapture, in Pope’s writings[30]; while Erickson relates this idea specifically to gender-bending fantasy blurred with Pope’s poetic self-concept, ecstasis also applies more broadly to the concept of imaginative freedom from physical limitation in multiple senses. In the dynamic tensions of Pope’s engagement with imagination, what stands out clearly is the element of overwhelming “wonder,” often imaged as the self-conscious recording of the self succumbing to the world of the imagination, in the Lockean sense of the imaged mental world.[31] This is evident in a well-known letter to John Caryll, Jr. (5 December 1712), in which Pope contrasts the life of the body, seen in the vigorous masculine animal spirits of his correspondent, to that of the imagination, where he dwells in an almost disembodied state, itself more real than the material world:

I am just in the reverse of all this Spirit & Life, confind to a narrow Closet, lolling on an Arm Chair, nodding away my Days over a Fire, like the picture of January in an old Salisbury Primer. I believe no mortal ever livd in such Indolence & Inactivity of Body, tho my Mind be perpetually rambling (it no more knows whither than poor Adrian’s did when he lay adying). Like a witch, whose Carcase lies motionless on the floor, while she keeps her airy Sabbaths, & enjoys a thousand Imaginary Entertainments abroad, in this world, & in others, I seem to sleep in the midst of the Hurry … ‘Tis … a serious truth I tell you when I say that my Days & Nights are so … equally insensible of any Moving Power but Fancy, that I have sometimes spoke of things in our family as Truths & real accidents, which I only Dreamt of….[32]

Writing to a Catholic correspondent, with a few strokes aimed at their current political problems, Pope combines Catholic tradition (the Salisbury Primer) with the popular folk elements of the witch’s trance, her “airy Sabbaths” implying both fantasy and exotic pleasures, along with the suggestion of the moments of consciousness between life and death, a particular focus at this time given the poet’s own health, and poetically expressed in the translation Adriani Morientis ad Animam then in discussion; both images describe the semi-willing loss of the empiricist, observing subject self, the mind located in the material body. “Fancy’s” associations with the trivial and delusory blend into a “moving Power” associated with mental life; nonetheless, even though Fancy itself is in this era linked with the creative fire of imagination, here it is also associated with the loss of “Spirit & Life,” with “Indolence,” and with insensibility. It is a “moving Power” in itself that has the power to blur distinctions between objective and subjective reality, between the self and the vision. This theme of the loss of the observing self recurs vividly through Pope’s early correspondence, often safely protected by an amused ironical tone as it is here. It will also form, however, the potent subject and inspiration of Pope’s final satire.

Pope’s lifelong enthusiasm for Homer, which fed his entire opus, had its own basis in his childish imagination, inspired by John Ogilby’s seventeenth-century translation of the Iliad, “that great edition with pictures,”[33] which would have been the young author’s equivalent of the comic book or superhero movie (or video game) of today, and which even in his later years he still spoke of “with a sort of rapture”[34] (see Figure 1). The distinctive centrality of elemental “wonder” in Pope’s understanding of Homer’s poetics becomes apparent when compared to the balanced assessment by his immediate forerunners in epic theory:

I shall not stick to make a previous Acknowledgement, that … [Homer’s] imagination is more pregnant [than Virgil’s]; that he hath a more universal fancy; … that he discovers more of that impetuosity, which makes the elevation of the Genius; that his expression is more pathetical; … that his Verses are fuller of pomp and magnificence; that they more delightfully fill the ear by their number and cadence, to such as know the beauty of versifying….[35]

Pope’s concept of the world of fable as “a new and boundless Walk for [the] Imagination” (Preface to Homer, 5) contrasts idiosyncratically to René Le Bossu’s widely-accepted treatise on the epic, which focuses on rationalizing the marvellous with the probable, blurring the distinction between the Aristotelian concept of “fable” as story and the notion of “fable” as an Aesopian moral tale:

These Fictions of Homer are, amongst other things, such as Horace commends in the Odysseïs, and which he finds to be equally beautiful and surprising, joyning together these two Qualifications, the Pleasant and the Marvellous, after the same manner that we have observed Aristotle did. But tho’ this Philosopher might have said thus much, certainly he never design’d to allow Men a full license of carrying things beyond Probability and Reason.[36]

The unstable and gendered distinction between the Homeric sweep of imagination and “all the Nurse and Priest have taught” is evidently in Pope’s time a dynamic, unresolved, and continuing substratum of critical discourse, through to Henry Fielding’s summarising of the received positions in Tom Jones, in the context of the emergent form of realistic prose fiction.[37] What is curious is the extent to which Pope’s poetic theory in the Homer preface directly engages this issue, playing off the ambiguity in the meaning of the term, in an affective commitment that continually challenges the oppositional model.

Figure 1

Plate 3 (Frontispiece), Homer His Iliads Translated, Book 1 (London: Printed by James Flescher, 1669).

Pope’s imaginative response to the supra-rational reflects the core principles of his classicism in the Essay on Criticism, where all true art finds its origins in the absolute, in “Unerring Nature,”[38] and in the apostolic revelation of the classical poets, whose rules of art are “discover’d, not devis’d” (Essay on Criticism, l. 88) and who partake of the same essence (their rules are “Nature itself”) and of the same authority—“Nor is it Homer Nods, but We that Dream” (Essay on Criticism, l. 180). This phrase seems intended to contrast to one of Pope’s stated models, Roscommon’s translation of Horace’s Ars Poetica, where “Homer himself had been observ’d to nod.”[39] The “admiring Eyes” that view “the world’s just Wonder” of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (Essay on Criticism, l. 248) are those of a rational judge who is moved by “generous Pleasure” and even “Rapture” (Essay on Criticism, l. 236, 238). St. Peter’s constitutes a “just Wonder” to be justly admired by “Men of Sense” (Essay on Criticism, l. 391); it is a substantive object, as opposed to rhetorical flourishes, “each gay Turn” that moves fools to “rapture” (Essay on Criticism, l. 390–91). Through the Essay on Criticism, millennial language and periphrasis expand the emotive scope and push linguistic decorum well beyond the generic limits of the ars poetica, seen for example in Pope’s description of the apostolic succession of ancient writers:

Essay on Criticism, l. 189, 191–94Hail Bards Triumphant!…

Whose Honours with Increase of Ages grow,

As Streams roll down, enlarging as they flow!

Nations unborn your mighty Names shall sound,

And Worlds applaud that must not yet be found!

Ironically, the superstition and ignorance of the monkish Dark Ages, a commonplace of Enlightenment rationalism, are driven off the world stage in terms that anticipate the landscape of the sublime, as Erasmus “Stemm’d the wild Torrent of a barb’rous Age” in his scholarship, which Pope portrays as “[Driving] those Holy Vandals off the Stage” (Essay on Criticism, l. 695–96). Even the terms of rational criticism borrow the language of cosmic wonder, as some of the worst critics are described as those whose “ratling Nonsense … Bursts out, resistless, with a thundering Tyde!” (Essay on Criticism, l. 628, 630).

The notion of communal authority central to both Pope’s Catholicism and his classicism shapes and justifies his response to the supra-rational, emphasizing the limits of individual human reason and allowing for wonder as an appropriate response. In the final lines of the Essay on Criticism, the “sounder Few” of the “unconquer’d, and unciviliz’d” race of British poets recognize the originary and divine qualities of Roman rules of classical form that can produce inspiration, “Wit’s fundamental Laws,” “restor’d” through enlightened wisdom (Essay on Criticism, l. 715–16, 719–22). Through the Essay on Criticism, a basically Catholic model of the submission of reason to faith and to spiritual authority is applied to the supra-rational poetic response of “wonder”—one that Pope sees as the willed submitting of rational critique in the face of the ineffable. A comparable model can be seen in Pope’s “Postscript” to the Odyssey, written in 1726,[40] which returns to the theme of Homer’s authority in response to critiques of his original preface as based on a French translation. While Pope claims “Tho’ I am a Poet, I would not be an Enthusiast,” it should be noted first that this claim occurs in the context of his specific political position as an English Catholic; the sentence moves swiftly to the parallel “and tho’ I am an Englishman, I would not be furiously of a Party” (“Postscript,” 397). Here Pope gives “enthusiasm” its specific political application, referring to the “inner light” associated with Puritan and sectarian rebellion in the previous century (suggested here in the “miserable misguided sects” [“Postscript,” 397]), directing attention away from the loyal English Catholics whom he represents: “my whole desire is but to preserve the humble character of a faithful Translator, and a quiet Subject” (“Postscript,” 397). Second, the Postscript reaffirms Homer’s authority while redefining admiration as a rational as well as passionate phenomenon: “as different people have different ways of expressing their Belief, some purely by public and general acts of worship, others by a reverend sort of reasoning and enquiry about the grounds of it; ‘tis the same in Admiration, some prove it by exclamations, others by respect” (“Postscript,” 396).

Pope’s own work thus embodies what Kenny calls the early modern “preoccupation with wonder”[41]—which bridged the worlds of fantasy, myth, and science. The eighteenth-century fascination with prodigies and miracles has been well noted, not just in the popular imagination as seen in almanacs and broadsheets, or in the empirical treatises of Defoe, but also from less likely scholarly sources, for example, an early treatise by Pope’s later literary executor William Warburton, A critical and philosophical enquiry into the causes of prodigies and miracles, as related by historians (London, 1727). Theories of the sublime and “the Pleasures of the Imagination”[42] in periodicals aimed at a middle-class reading public; the persistent popularity of romance, epic, and fantasy literature; the breathless responses to the newly-discovered wonders of science; the quasi-mythical overtones of travel literature, with its blurring of fact and fantasy—all these are now well-recognized features of the so-called “Age of Reason,” revising traditional oppositional notions of the landscape of the early Enlightenment. Pope’s early correspondence embodies much of this element of wonder, often with an over-the-top ironic self-awareness, ranging from Catholic-tinged fantasy in letters to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, to self-conscious philosophizing about the cosmos and human nature to his Catholic friend John Caryll, in passages that anticipate similar themes of human inconsistency and the scientifically-expanded chain of being in An Essay on Man:

This minute, perhaps, I am above the stars, with a thousand systems round about me, looking forward into the vast abyss of eternity, and losing my whole comprehension in the boundless spaces of the extended Creation … [and] the next moment I am below all trifles, even grovelling with T[idcombe] in the very centre of nonsense…. Good God! What an Incongruous Animal is Man? how unsettled in his best part, his soul; and how changing and variable in his frame of body? … Who knows what plots, what achievements a mite may perform, in his kingdom of a grain of dust, within his life of some minutes? And of how much less consideration than even this, is the life of man in the sight of that God, who is from ever, and for ever![43]

It is not surprising that this rather purple youthful passage, which was originally written to Caryll, was later reprinted as if to Addison, as if to suggest coincidence with his Spectator essays on the stretch of imagination and theories of the sublime. The letter is also characteristic of the Longinian principle of the submerging of the self, the blurring of subject and object, in the contemplation of the sublime.[44] Pope goes on to say: “’Tis enough to make one remain stupefied in a poise of inaction, void of all desires, of all designs, of all friendships.”[45] For Pope, self is recovered, and only barely, through social relationships that affirm human meaning (in this instance, a compliment to his correspondent). What is notable here is that the effect of “wonder” can, in its most extreme form, translate into dullness, a “stupefied” insensibility to human desire or friendship, which is a key element in the satiric vision of the final Dunciad; here as elsewhere for Pope the quality of imagination overwhelms the physical senses and thus paradoxically links inspiration with dullness. In the letter to John Caryll cited earlier, for example, his “moving Power [of] Fancy” leaves him in a “stupid settled Medium” insensible to pleasure and pain, and isolated from family relationships.[46] This paradox underlies the relationship between satire and sublimity in the final Dunciad, where it reaches its culminating expression.[47]

Pope’s relationship to wonder and the non-rational is complicated by his own Catholicism, a faith popularly associated with “superstition” and the irrational, and which shapes and informs the classicism of the Essay on Criticism.[48] Pope’s lifelong efforts to represent Catholicism as a faith compatible with civilized English rationalism are seen notably in his letters to his co-religionists, in which he deplores “weak superstition,” and mocks an Anglican clergyman for his enthusiasm over Geoffrey of Monmouth’s British History:

The poor Man is highly concerned to vindicate Jeffery’s veracity as an Historian; and told me he was perfectly astonished, we of the Roman Communion could doubt of the Legends of his Giants, while we believ’d those of our Saints? I am forced to make a fair Composition with him; and by crediting some of the Wonders of Corinaeus and Gogmagog, have brought him so far already, that he speaks respectfully of St. Christopher’s carrying Christ, and the Resuscitation of St. Nicholas Tolentine’s Chickens. Thus we proceed apace in converting each other from all manner of Infidelity…. This amazing Writer [i.e. Geoffrey of Monmouth] has made me lay aside Homer for a week, and when I take him up again, I shall be very well prepared to translate with belief and reverence the Speech of Achilles’s Horse.[49]

Despite his depreciatory comments, Pope eventually took this story as inspiration for his unwritten British epic “Brutus,” while the speech of Achilles’s horse enters the ambiguous but sweeping status of the world of fable. Pope admits his own attraction to the world of romance, again with self-protective ambivalence, in a letter to Judith Cowper of 26 September 1723 (as he is coming to an end of Homer translation and entering the period which saw the genesis of both the first Dunciad and the Essay on Man): “I have long had an inclination to tell a Fairy tale; the more wild & exotic the better, therefore a Vision, which is confined to no rules of probability, will take in all the Variety & luxuriancy of Description you will. Provided there be an apparent moral to it.”[50]

As Pope describes himself to John Caryll, Jr. in 1712, in fanciful terms that reflect “all the Nurse and Priest have taught” at the time he is writing the poem which makes that phrase famous, so too the world of imagination and its limiting definition in parody, the strategy of hyperbolic rhetoric and the sublime challenge to human limitation, coincide repeatedly through his work. In The Rape of the Lock, Belinda’s sparkling cross, “Which Jews might kiss, and Infidels adore,”[51] invokes the apocalyptic imagery of the time, conflating an afternoon junket by the heroine and her cronies with the Second Coming of Christ. Yet Pope’s phrasing also creates a weirdly disjunctive moment in which Belinda appears to be sharing her seat on the barge in close intimacy with a host of Christian converts on the Day of Judgement.[52] Similarly, at the end of the poem, “after all the Murders of your Eye, / When, after Millions slain, your self shall die” (The Rape of the Lock, V.145–46), the deliberately exhausted Petrarchan hyperbole is stretched and loosened from its referent, as the mere scale of the term “Millions slain,” as well as its lack of agent, suggests not a string of disappointed lovers or even a Homeric battlefield, but the long march of history and human deaths over time.

The aphoristic and rhetorical character of the Essay on Man sometimes obscures for us the stunningly cosmic, deeply ecological frame of reference that embodies and expands its critique of the limitations of human reason. The opening passage, with its allusion to Paradise Lost, generates a key disjunction between the highest epic intent ever proclaimed in English and a world insufferably constrained by rationalism: two hunting gentlemen trample casually through an “ample field” that could be either a “Wild” or Edenic “garden,” looking for human follies to shoot with words.[53] (It is worth noting that throughout the Essay on Man hunting is sharply critiqued as an expression of human arrogance, entitlement, and original sin.) Their activity is itself undercut, however, by human limitation. Pope’s language here precisely distils the conjunction of sublimity and satire, as a reflection on the fundamental absurdity of human existence, itself the quintessence of wonder and cynicism, is reduced to a parenthetical expression thrust into the middle of a verb phrase: “Let us (since Life can little more supply / Than just to look about us and to die”) / Expatiate free…” (Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 3–4). Here the activity of “Expatiat[ing],” associated in Pope with imagination freed of bodily limitations, is sharply constrained by both human mortality and satiric puncture, a pattern that repeats throughout the Essay on Man. For example, the allusion to the Longinian sublime perspective on cosmic “vast immensity” in the following passage encapsulates this effect, as this perspective is put beyond human reach, with Horatian adversarial panache: “He, who thro’ vast immensity can pierce, / See worlds on worlds compose one universe … May tell why Heav’n has made us as we are, / But of this frame … has thy pervading soul / Look’d thro’?” (Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 23–24, 28–29, 31–32). A similar disjunction occurs in the concluding couplet, as the two hunting gentlemen propose to use genteel conversational satire to speak on God’s behalf: “Laugh where we must, be candid where we can; / But vindicate the ways of God to Man” (Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 15–16). Yet, according to Pope, these are the two lines that “contain the main design that runs through the whole.”[54] Whatever the creaky discomfort of this couplet, the poet’s aim in the Essay on Man is of a piece with Milton’s: to demonstrate the justice of God’s ways, not specifically through the Biblical view of history, but through a challenge to human rationality and limited perception, closely related to Addison’s justification for the response of wonder, and informed by Pope’s own Catholic notions of human limitation: “to reason right, is to submit” (Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 164).

As if in response to this couplet’s tonal disjunction, the poem’s description of humanity’s nature and place in the universe partakes of a cosmic sublimity in which Horatian satire coalesces with the continually erased presence of Milton’s epic. Angels are hurled from their places in universal destruction, in scenes echoing Satan’s account of the battle in heaven (“and shook his throne”[55]), while newly-discovered interstellar space is violently dissolved in an apocalypse in which the laws of physics have been erased. The worlds of Miltonic epic, Biblical tradition, and contemporary science, all appropriate subjects of sublimity, are blurred together in an apocalyptic vision in which reductive parody becomes the main theological point, hammered home with conversational flourish pushing the limits of Horatian decorum:

Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 251–58Let Earth unbalanc’d from her orbit fly,

Planets and Suns run lawless thro’ the sky,

Let ruling Angels from their spheres be hurl’d,

Being on being wreck’d, and world on world,

Heav’n’s whole foundations to their centre nod,

And Nature tremble to the throne of God:

All this dread ORDER break—for whom? for thee?

Vile worm!—Oh Madness, Pride, Impiety!

Humans commit the sin of pride on a Luciferian scale; it should be noted that the sin committed here is in fact the orthodox view of human exceptionalism based on reason, expressed in quotidian activities like hunting and meat-eating, expanded to an apocalyptic scale in “destroy all Creatures,” and represented by Pope as a colossal sin against nonhuman nature, and thus against God’s providential order. Notably, the poet links “reason” with the irrational emotion of pride, the primal sin:

Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 117–24Destroy all Creatures for thy sport or gust,

Yet cry, if Man’s unhappy, God’s unjust;

If Man alone ingross not Heav’n’s high care,

Alone made perfect here, immortal there:

Snatch from his hand the balance and the rod,

Re-judge his justice, be the GOD of GOD!

In Pride, in reas’ning Pride, our error lies;

All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies.

The fall of Lucifer still inhabits the description of humanity in Epistle 2 of Essay on Man, a passage later admired for its sublimity by Samuel Johnson: humanity itself—“sole judge of Truth, in endless Error hurl’d: / the glory, jest, and riddle of the world!” (l. 17–18)—is Rochester’s “prodigious” monster, now a “wondrous creature” to be exhibited as a curiosity (l. 19, 34). Here Pope invokes another source of wonder in the period, the fascination with mixture and monstrosity, prodigies and events beyond the perceived laws of nature. The sweeping dismissal of traditional views of reason culminates in the poem’s ending, as human nature is redeemed not through reason, balance, and limitation, but through the qualities of unbounded imaginative vision and empathy; the concluding passage, which echoes the animate universe of Epistle 1, dissolves the constraints of rationality and restores the perspective of wonder, with a vision of human imaginative charity, “boundless” as Homer’s world of fable, and on an equally cosmic scale:

Essay on Man, Epistle 4, l. 368–72Wide and more wide, th’o’erflowings of the mind

Take ev’ry creature in, of ev’ry kind;

Earth smiles around, with boundless bounty blest,

And Heav’n beholds its image in his breast.

The conclusion of the fourth book of The Dunciad was also cited by Johnson as one of the great examples of the sublime in English verse,[56] in which a poem originally intended as a satire on false learning and the misuse of reason morphs into the inverted apocalypse brought about by Dulness’s “uncreating Word”—“Thus at her felt approach, and secret might, / Art after Art goes out, and all is Night.”[57] The poem takes the satiric mode of parody, which depends on shared reason, and pushes it beyond the edge into the supra-rational, where even the poetic consciousness itself is overwhelmed, in what amounts to an eyewitness account of the ending of cultural consciousness as Pope knows it.[58] It is not surprising that The Dunciad was of all Pope’s poems the one he most obsessively revised through much of his career: it powerfully enacts a persistent theme in his writing, not only of the lure of insensibility (an attraction which underlies the intensity of his satiric attacks on that quality), but also of the tendency for imaginative wonder to overwhelm the hyper-conscious self, to verge from extreme sensibility to stupefaction, to separate the self from social connection and perspective, a powerful theme throughout the poem.[59] The Dunciad culminates Pope’s struggle with these contradictions. It blurs the distance requisite for mock-heroic; its sweep of parody recreates the immensity of the sublime, as it paradoxically documents the death of poetic consciousness through a hyper-conscious medium that both challenges the boundaries of perception and unwrites itself in the process. Unlike the conventional epic invocation, in this one the “song,” the heroic Homeric perspective, is not going to outlast and immortalize the epic action; here the action itself, the restoration of the empire of Dulness, will outlast the song, subsuming it, even consuming it, as the subject matter devours its own artistic medium. This point is stressed in the material nature of the text. The dream/prophecy of Book 3 shifts to its fulfilment in present reality (1742), a narrative record from which even the author has disappeared, and the poem, a tattered physical object, “Found in the Year 1742,” is all that is left. The asterisks, or “chasm” (editorial term for a torn page), immediately following the final desperate command to the Muse, turn the poet’s song—a list reminiscent of his late satires—into a sub-verbal absurdity, an ellipsis, ripped away from the tattered and flimsy document that is all that is left of civilization and Arts:

The Dunciad, Book 4, l. 619–28Oh Muse! relate (for you can tell alone,

Wits have short Memories, and Dunces none)

Relate, who First, who last resign’d to rest;

Whose Heads she partly, whose completely blest;

What Charms could Faction, what Ambition lull,

The Venal quiet, and entrance the Dull;

’Till drown’d was Sense, and Shame, and Right, and Wrong—

Oh sing, and hush the Nations with thy Song!

* * * * * * *

In vain, in vain,—the all-composing Hour

Resistless falls; The Muse obeys the Pow’r.

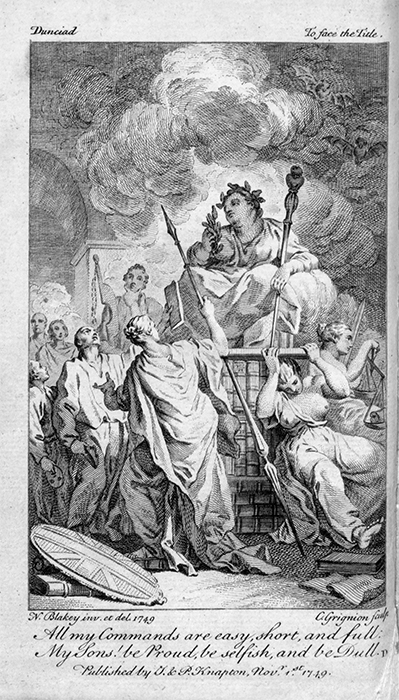

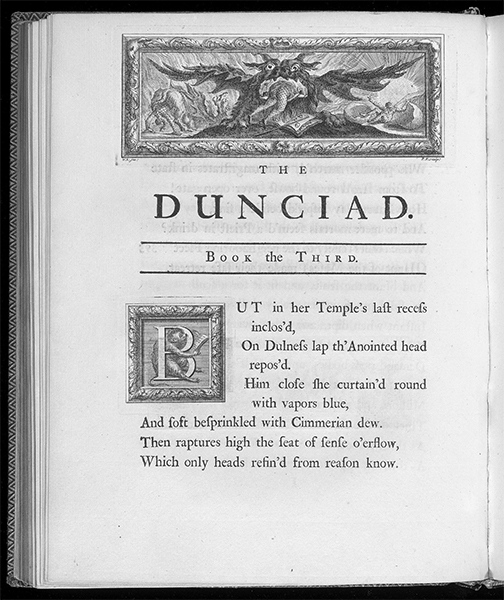

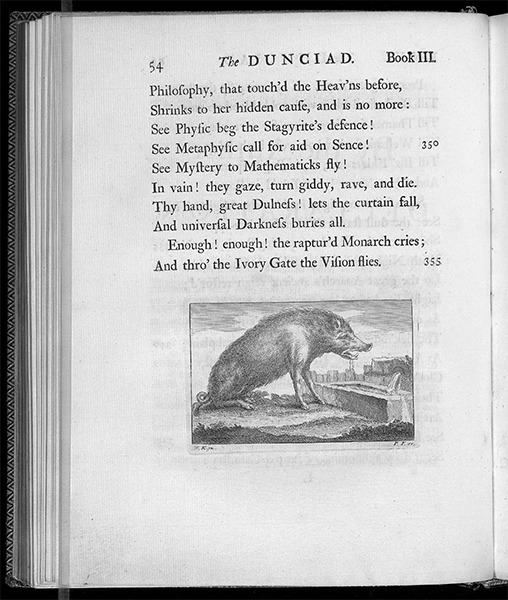

The idea of the poet’s complicity with Dulness, ironically stressed by the Scriblerian commentary (“this is an invocation of much Piety” in which the poet declares his impatience to be re-united with Dulness—“Suspend a while your Force inertly strong, / Then take at once the Poet and the Song”),[60] is seen in the frontispiece to a 1749 octavo edition produced by the Knaptons, closely associated with Pope and Warburton in the final years of the former’s life, and soon to be publishers of the Warburton edition of the poet’s works. This illustration (Figure 2) features a hugely fat Dulness, on her throne supported by guardian virtues, and, on the left amongst the Hogarthian crowd surrounding her, almost on the margin of the picture, a small and thin figure holding up a book as though in offering.[61] Perhaps even more illustrative of the relation of parody and the sublime in the poem’s material presentation are some of the opulent engravings that accompanied the three-book Dunciad in the 1735 quarto edition of Pope’s works, Volume 2 (the magisterial volume long recognized as culminating the author’s self-presentation in print). The engravings, designed by Pope’s friend William Kent, the architect and landscape artist, and realized by the famed French engraver Peter/Pierre Fourdrinier, form a substantive part of the book’s commercial and interpretive presence. They are fulsomely advertised as “expensive ornaments,” “Copper Plates, design’d by Mr. Kent,” and produced in limited numbers in order to match the existing collections of Pope’s works and the Homer translations.[62] These elaborate copper plates are thus not only an expression of Pope’s legendary control over the material production of his texts, but also associated in contemporary readers’ minds with the poet’s bardic self-portrait and his Homeric enterprise. They thus reside in the landscape of specific satire, as Ileana Baird observes, while using their baroque energy to evoke a subversive imaginative realm. Two of them bracket the third book of the Dunciad Variorum, which represents a mock-apocalypse through the pantomime stage and a prophecy as yet unrealized. It opens with a headpiece portraying a startling image of the owl of Dulness, now expanded into a monstrous figure evoking images of Hell-mouth in medieval drama (Figure 3);[63] it closes with vignettes, one emblematic and allegorical, of a swan being carried off by an eagle (or vulture), and one more enigmatic, of an enormous and solitary boar at a trough, who dominates what appears to be a decayed classical landscape (Figure 4). This closing tailpiece fills in the space following the poem’s then-final lines, the saving distancing of the prophetic vision into the “Iv’ry Gate” of false dreams. The image of the boar evokes themes of consumption and decay, but the size of the animal, like the owl in the headpiece, dominates the picture. It is an entirely non-verbal entity, with no visible relation to the human either as farm animal or hunting quarry. Where the language of poetry appears to write itself out of existence, through its own polished form, the visual images present an unsettling and non-rational commentary.

Figure 2

Plate 1 (Frontispiece), The Dunciad, complete in four books, according to Mr. Pope’s last Improvements. With Several Additions now first printed, and the Dissertations on the Poem and the Hero, and Notes Variorum. Published by Mr. Warburton (London: J. and P. Knapton, 1749).

Figure 3

Headpiece, The Dunciad in Three Books, Book 3, in The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, Volume 2 (London: Printed by John Wright for Lawton Gilliver, 1735).

Figure 4

Tailpiece, The Dunciad in Three Books, Book 3, in The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, Volume II (London: Printed by John Wright for Lawton Gilliver, 1735).

The early eighteenth century—with its self-conscious theorizing of the sublime and its deep mistrust of “Enthusiasm” as a recipe for civil unrest—negotiated the human response of wonder through parody, through personified abstractions, through prose analysis, and through millennialist tropes. Pope transcends these limitations through a poetic language and a mode of poetic wonder that is the more powerful for the precision with which it is expressed.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Originating with Cicero, the phrase was popularised in humanist tradition through its application in Horace (Epistle 1.6). See Stephanie McCarter, Horace Between Freedom and Slavery: The First Book of “Epistles” (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2015), 107 and following, and W. Y. Sellar, The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Horace and the Elegiac Poets (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892), 95, for observations on this concept in Horace’s writing and thought.

-

[2]

Rebecca Ferguson, The Unbalanced Mind: Pope and the Rule of Passion (Brighton: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1986); David Fairer, Pope’s Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984).

-

[3]

Ferguson, The Unbalanced Mind, 136, citing Peter Dixon, The World of Pope’s Satires: An Introduction to the “Epistles” and “Imitations of Horace” (London: Methuen, 1973), 164.

-

[4]

Epitomised in this period in the frequent editions, translations, and reproductions of Peri Hupsos (De Sublimitate) by Cassius Longinus (213–273 CE). See note 9 below.

-

[5]

Neil Kenny describes the early modern “preoccupation with wonder” as a feature of the period in his “Introduction” to a special issue on wonder in early modern Europe of Nottingham French Studies (56, no. 3 [2017]: 249–55, excerpt quoted on p. 249).

-

[6]

For the identification of wit with “life-giving” creative force in early modern criticism, see for example the classic essay by Edward Niles Hooker, “Pope on Wit: The Essay on Criticism” (1951), in Essential Articles for the Study of Alexander Pope, ed. Maynard Mack (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1964), 175–97.

-

[7]

In addition to a valuable analysis of the historical roots of the term, Fairer’s study focuses perceptively on the dualities of imagination oscillating between delusion and perception in Pope (see Pope’s Imagination, particularly 57–63 and 93–105).

-

[8]

The Spectator, Vol. 6 (London: S. Buckley and J. Tonson, 1713), nos. 411–21. All subsequent quotations are taken from this edition.

-

[9]

Quotations are taken from An Essay upon the Sublime. Translated from the Greek of Dionysius Longinus Cassius, the Rhetorician. Compar’d with the French of Sieur Despreaux Boileau (Oxford: Printed by L.L. for T. Leigh, 1698); page numbers are provided infra-textually. This edition is an early example of the efflorescence of translations and annotated editions of Longinus through the late seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth in England; the treatise was widely published in Europe in the sixteenth century, in Greek and Latin, and rendered even more popular through translations, notably Boileau’s 1674 rendition into French, in the next. See Dorothy Gabe Coleman, “Montaigne and Longinus,” Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 47, no. 2 (1985): 405–13, for an excellent brief outline of the European tradition. Its popularity continues today, from the classic monograph by Samuel Holt Monk, The Sublime: A Study of Critical Theories in XVIII-Century England (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1960), to monographs reflecting current interest in emotion and aesthetics such as James Kirwan, Sublimity: The Non-Rational and the Irrational in the History of Aesthetics (London: Routledge, 2005), to such full-length collections as Andrew Ashfield and Peter de Bolla, eds. The Sublime: A Reader in British Eighteenth-Century Aesthetic Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) and Timothy M. Costelloe, ed. The Sublime: From Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). These collections of primary material to some extent correct a tendency to read Augustan classical theory through the lens of Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke, and to see its popularity as arising from seventeenth-century rhetorical and emergent aesthetic theory. The links between classical rhetoric and aesthetic sensationalism provided by Longinian theory are still being explored.

-

[10]

“He, who thro’ vast immensity can pierce, / See worlds on worlds compose one universe / … May tell us why Heav’n has made us as we are” (Epistle 1, l. 23–24, 28); quoted from Alexander Pope: An Essay on Man, ed. Maynard Mack (London: Methuen, 1950), 15–16. All subsequent references to this work are taken from this edition. Pope is emphasising in this passage that humans (and/or his adversarius Bolingbroke) do not have this cosmic perception of the whole. While the poet is highlighting human limitations, the passage’s evocation of recognized images of sublimity should be noted.

-

[11]

These tendencies are examined and interrogated in Jonathan Lamb, “Longinus, the Dialectic, and the Practice of Mastery,” English Literary History 60, no. 3 (Autumn 1993): 545–67. See also Costelloe’s description of “Longinian” rhetorical mastery in contrast to the aesthetic valuation of sublimity in his account of Shaftesbury (“Imagination and Internal Sense: The Sublime in Shaftesbury, Addison, Reid, and Reynolds,” in The Sublime: From Antiquity to the Present, cited above, 50–63, citation from p. 52). What is not discussed is how clearly Longinus analyses this dynamic in the original text.

-

[12]

For a discussion of the religious nature of this theory in Longinus’s own time see Casper C. de Jonge, “Dionysius and Longinus on the Sublime: Rhetoric and Religious Language,” The American Journal of Philology 133, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 271–300.

-

[13]

Essay on Criticism, line 152 from Alexander Pope: Pastoral Poetry and An Essay on Criticism, ed. E[mile] Audra and Aubrey Williams (London: Methuen, 1961), 257. All subsequent citations are taken from this edition.

-

[14]

John Dennis, The advancement and reformation of modern poetry: A critical discourse. In two parts (London: Printed for Rich. Parker, 1701), 24.

-

[15]

Ibid., 26.

-

[16]

Ibid., 45.

-

[17]

Addison’s pivotal influence is perceptively analysed by William H. Youngren, “Addison and the Birth of Eighteenth-Century Aesthetics,” Modern Philology 79, no. 3 (February 1982): 267–83.

-

[18]

Joseph Addison, The Spectator, no. 412 (Monday, 23 June 1712): 88–89.

-

[19]

Joseph Addison, The Spectator, no. 413 (Tuesday, 24 June 1712): 95.

-

[20]

Ibid., 96.

-

[21]

Pope was influenced by the Pyrrhonism of Michel de Montaigne, whose works he read in some detail, and by the fideistic skepticism of Blaise Pascal, whom he cites as a model in his correspondence. Coleman argues convincingly for Montaigne’s connection with Longinian principles in her 1985 essay on the subject (see note 9 above).

-

[22]

Letter from Alexander Pope to Ralph Bridges, 5 April 1708, in George Sherburn, ed. The Correspondence of Alexander Pope (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 1:44.

-

[23]

Preface to The Iliad of Homer. Translated by Mr. Pope (1715), in Alexander Pope, The Iliad of Homer, Books I–IX, ed. Maynard Mack (London: Methuen, 1967), 4. All subsequent quotations referring to this translation (abbreviated as Preface to Homer) are taken from this edition; they are provided infra-textually.

-

[24]

Fairer, Pope’s Imagination, 4–5.

-

[25]

Ibid., 7.

-

[26]

Longinus applies this imagery specifically to oratory: “For as lofty and rais’d Subjects by their torrent and violence, naturally transport and carry all before them: so they require out of course strong expressions, and leave no time for the Hearer to amuse himself with harping on the number of the Metaphors, but throw him into the same rapture with the Speaker” (An Essay upon the Sublime, 65–66). The “rapture” referred to here as belonging to both orator and listener, in shared performative experience, links rhetorical theory with later models of responsive aesthetics in an asynchronous textual experience, eliding of poet and reader in the same “Poetical Spirit.”

-

[27]

An Essay on Criticism, l. 391, 284.

-

[28]

Letter from Alexander Pope to John Caryll [Sr.], 21 December 1712, in The Correspondence of Alexander Pope, 1.168.

-

[29]

An Essay on Man, l. 5, in Alexander Pope: An Essay on Man, edition cited above. All subsequent references to this work will be taken from this edition.

-

[30]

Robert A. Erickson, “Pope and Rapture,” Eighteenth-Century Life 40, no. 1 (January 2016): 4, 9. In this article (9, 31n), Erickson comments helpfully on Maynard Mack’s observations concerning Pope’s lifelong association with “rapture” (his own, and as viewed by others) in his biography Alexander Pope: A Life (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985).

-

[31]

As opposed to delusive dreams, though the distinction between the two can often be blurred, as Fairer observes (Pope’s Imagination, 4–5, 18–23, 31–33).

-

[32]

Letter from Alexander Pope to John Caryll, Jr., 5 December 1712, in The Correspondence of Alexander Pope, 1.163.

-

[33]

James M. Osborn, ed. Joseph Spence: Observations, Anecdotes, and Characters of Books and Men (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966), 1.14.

-

[34]

Ibid., 1.14. See also Mack, Alexander Pope: A Life, 45, and Erickson, “Pope and Rapture,” 9.

-

[35]

René Rapin, Observations on the Poems of Homer and Virgil, trans. John Davies (London, 1672), 6–7.

-

[36]

René Le Bossu, Monsieur Bossu’s Treatise of the Epick Poem … Done into English … by W. J. (London, 1695), 138.

-

[37]

Henry Fielding, Tom Jones, ed. Sheridan Baker (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973), 301–8; Book VIII, Ch. 1.

-

[38]

An Essay on Criticism, cited above, l. 70, 246. Subsequent line references may be found infra-textually.

-

[39]

Wentworth Dillon, Earl of Roscommon, Horace: Of the Art of Poetry: A Poem (London: Printed and sold by H. Hills, 1709), 13. The model of literary classicism in An Essay on Criticism, a piece written while Pope was still in the heart of his Catholic community, is closely parallel to the English recusant notion of religious authority, that of communal tradition through time passed down by means of embodied models of original divine authority (as opposed to the “dead letter” of Protestant bibliolatry and emphasis on individual experience). See George H. Tavard, The Seventeenth-Century Tradition: A Study in Recusant Thought (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1978), 74, 87, and passim. Pope links Catholic models of tradition with classical, specifically Longinian, models of the god-like qualities of great writers, as they embody a supra-rational irresistible authority (in all senses of that term). However, while Longinus uses imagery of Delphic oracles to describe the effect of great writers on their followers, through transmitting the divine spirit directly (An Essay upon the Sublime, 33), Pope transmutes that notion into the sense of a communal tradition of formal rules developed over time, giving humble modern worshippers access to that divine power through formal “Rules” as opposed to individual inspiration.

-

[40]

Alexander Pope, The Odyssey of Homer, Books XIII–XXIV, ed. Maynard Mack (London: Methuen, 1967), 382–97. Subsequent references can be found infra-textually.

-

[41]

See footnote 5 above.

-

[42]

Joseph Addison, The Spectator, no. 411 (21 June 1712): 84.

-

[43]

Letter from Alexander Pope to John Caryll, Jr., 14 August 1713, The Correspondence of Alexander Pope, 1.185–86.

-

[44]

A feature of Longinus outlined by Christopher Fanning in “The Scriblerian Sublime,” Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 45, no. 3 (Summer 2005): 655.

-

[45]

Letter cited above in footnote 43, 1.186.

-

[46]

Letter from Alexander Pope to John Caryll, Jr., 5 December 1712, cited above in footnote 32, 1.163.

-

[47]

The relationship of satire and sublimity is well outlined in Fanning’s essay (see footnote 44 above), which explores their rhetorical closeness and corrects post-Romantic teleology. See also James Noggle, The Skeptical Sublime: Aesthetic Ideology in Pope and the Tory Satirists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001): “The Dunciad tends to figure such convergences of degraded arts and a broad skeptical destabilization as manifestations of the sublime, an aesthetic and cognitive field of experience marking the limits of our capacity to experience and to know” (194). Finally, an excellent assessment of the relationship of satire to sublimity in the Scriblerians’ work is made by Bill Knight, who points out that the blurring of sublimity and parody in their attack on modernity performs “a commitment to the ethical and poetic qualities of the Longinian notion of the sublime itself.” See Bill Knight, “Boileau’s Longinus, Imitative Translation, and the Scriblerians: Neoclassicism as Event,” Colloquy: Text, Theory, Critique 32 (2016): 66.

-

[48]

See Katherine M. Quinsey, “‘No Christians Thirst for Gold!’: Religion and Colonialism in Pope,” Historical Reflections / Réflexions historiques 32, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 562, 572–74.

-

[49]

Letter from Alexander Pope to Edward Blount, 8 September 1717, The Correspondence of Alexander Pope, 1.425. Sherburn remarks that all the Edward Blount correspondence is “suspiciously doctored” and could originate in letters to Caryll, another notable Catholic friend.

-

[50]

Letter from Alexander Pope to Judith Cowper, 26 September 1723, The Correspondence of Alexander Pope, 2.202.

-

[51]

Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems, ed. Geoffrey Tillotson (London: Methuen, 1962), 159; Canto II, l. 7.

-

[52]

This observation is part of an extended study of myth and parody in The Rape of the Lock and some other of Pope’s works. See Katherine M. Quinsey, “Ridicule’s Two Edges: Myth, Parody, and the Reader in Pope,” in Elizabeth Maslen, ed. Comedy: Essays in Honour of Peter Dixon by Friends and Colleagues (London: Queen Mary and Westfield College, 1993), 161.

-

[53]

An Essay on Man, Epistle 1, l. 7–8, 13–14; in Alexander Pope: An Essay on Man, cited above, 13–14. Subsequent references to this work can be found infra-textually. This observation is discussed in K. M. Quinsey, “Dualities of the Divine in the Essay on Man and the Dunciad” (2002), reprinted in Religion in the Age of Reason: A Transatlantic Study of the Long Eighteenth Century, ed. Kathryn Duncan (New York: AMS Press, 2009), 144.

-

[54]

November 1730; Osborn, Joseph Spence, edition cited above, 1.131, no. 299. See Quinsey, “Dualities of the Divine in the Essay on Man and the Dunciad,” 144.

-

[55]

John Milton, Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books (1674), in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, ed. Stephen Greenblatt et al., 8th ed. (New York: Norton, 2006), 1834: Book 1, l. 105.

-

[56]

According to Boswell, Johnson could recite the final verses of The Dunciad from memory and “talked loudly in praise of these lines.” See James Boswell’s Life of Johnson (London: Oxford University Press, 1953), 411.

-

[57]

Alexander Pope, The Dunciad, in Four Books. Printed According to the complete Copy found in the Year 1742 (1742), in Alexander Pope: The Dunciad, ed. James Sutherland (London: Methuen, 1963), Book 4, l. 639–40. Further references to this work will appear parenthetically in the text.

-

[58]

On this point see the discussion in Quinsey, “Dualities of the Divine in the Essay on Man and the Dunciad,” 151.

-

[59]

See the discussion of Pope’s correspondence above.

-

[60]

The Dunciad, Book 4, l. 7–8, and note 1, 399–400. Fanning points out the merging of subject and object in the sublime, exemplified in this passage (“The Scriblerian Sublime,” 655).

-

[61]

The Dunciad, complete in four books, according to Mr. Pope’s last Improvements. With Several Additions now first printed, and the Dissertations on the Poem and the Hero, and Notes Variorum. Published by Mr. Warburton (London: J. and P. Knapton, 1749). The illustration is designed by Nicholas Blakey and engraved by Charles Grignion. The interpretive quality of this illustration, particularly its evocation of the self-fulfilling dream of the Dunces, is usefully discussed by Ileana Baird, “Visual Paratexts: The Dunciad Illustrations and the Thistles of Satire,” in Book Illustration in the Long Eighteenth Century: Reconfiguring the Visual Periphery of the Text, ed. Christina Ionescu (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 349–351. Baird also points out the pivotal position of this engraving in the transition from the personal and satiric quality of the Kent-Fourdrinier ornaments to the more “theatrical” and sentimentally oriented engravings of Warburton’s mid-century edition (351–52, 364–66). The personal and satiric effect of the 1735 quarto engravings in fact intensifies the emotive impact of wonder, as they push at the boundaries of rococo conventions in their exploitation of animal emblems, and their invocation of monstrosity and landscape (discussed below).

-

[62]

R. H. Griffith, Alexander Pope: A Bibliography (London: The Holland Press, 1962), vol. 1, Part II, 287.

-

[63]

Discussed in detail for its allusions to both contemporary pantomime and anti-Catholic tradition in Quinsey, “Dualities of the Divine in the Essay on Man and the Dunciad,” 146.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Plate 1 (Frontispiece), The Dunciad, complete in four books, according to Mr. Pope’s last Improvements. With Several Additions now first printed, and the Dissertations on the Poem and the Hero, and Notes Variorum. Published by Mr. Warburton (London: J. and P. Knapton, 1749).

Figure 3

Figure 4