Abstracts

Abstract

During the health crisis, the elderly were identified as being among those most at risk of developing complications in the event of contamination by the virus, so in Italy, Canada and many other parts of the world, various specific measures were implemented to protect them. However, these have mainly involved measures to reduce both physical and social contact. This has led to repercussions not only on the social and psychological well-being of seniors but also on their social participation and inclusion. According to these aspects, in this article we analyze the situations and experiences of the elderly (aged seventy and over) in rural areas, in Italy and Canada, trying to highlight the socio-territorial effects of this health crisis on seniors. Therefore, on one hand, the aim is to identify the aspects that have accentuated the vulnerability of seniors and, on the other hand, the protective and supportive measures that have enabled them to cope with the pandemic crisis and its consequences. Furthermore, we will illustrate the different efforts to respond to the complex issue of ageing (demographic dimension) within rural areas (socio-territorial dimension) in an emergency-pandemic context (socio-health dimension), asking whether or not the initiatives and processes implemented by a variety of actors (non-profit associations, local or public institutions) respond to the needs and requirements of seniors living (in) the areas under study.

Keywords:

- elderly,

- rural areas,

- pandemic,

- social exclusion,

- social innovation

Résumé

Lors de la crise sanitaire, les personnes âgées ont été identifiées comme étant parmi les plus à risque de développer des complications en cas de contamination par le virus de la COVID-19. Pour cette raison, en Italie, au Canada et dans de nombreuses autres parties du monde, diverses mesures spécifiques ont été mises en place dans le but de les protéger. Cependant, il s’agit principalement de mesures visant à réduire les contacts physiques et sociaux. Cela a eu des répercussions non seulement sur le bien-être social et psychologique des personnes âgées, mais aussi sur leur participation et leur inclusion sociale. Dans cet article, nous analysons les situations et les expériences des personnes âgées (70 ans et plus) dans des zones rurales, en Italie et au Canada (Québec), en essayant de mettre en évidence les effets socio-territoriaux que cette crise sanitaire a pu avoir sur les personnes âgées. Il s’agit donc, d’une part, d’identifier les aspects qui ont accentué la vulnérabilité des personnes âgées et, d’autre part, les mesures de protection et de soutien qui leur ont permis de faire face à la crise pandémique et à ses conséquences. En plus, nous illustrerons les différents efforts déployés pour répondre à la question complexe du vieillissement (dimension démographique) dans les zones rurales (dimension socio-territoriale) dans un contexte d’urgence et de pandémie (dimension socio-sanitaire), en nous demandant si les initiatives et les processus mis en œuvre par une variété d’acteurs (associations à but non lucratif, institutions locales ou publiques) peuvent ou non répondre aux besoins et aux exigences des personnes âgées vivant (dans) les zones à l’étude.

Mots-clés :

- Personnes âgées,

- zones urbaines et rurales,

- pandémie,

- exclusion sociale,

- innovation sociale

Article body

01. Introduction: defining social exclusion in later life

Moving from a qualitative analysis based on a total of 177 interviews (which involved 110 seniors and 71 social and health professionals and/or stakeholders, both in the Italian and Canadian territories) our article aims to highlight both seniors’ pre-pandemic needs and the dynamics of social exclusion with which the elderly in rural areas may have been faced in a pandemic situation such as the one caused by Covid-19, and to provide an understanding of the social, territorial, political and economic mechanisms through which the pandemic may have influenced the lifestyles of seniors living (in) the rural areas of the territories under study. In the article, our findings will be used to show the different attempts to respond to the complex issue of ageing (demographic dimension) in rural areas (socio-territorial dimension) in a pandemic situation (sociosanitary dimension), asking whether or not the initiatives and processes implemented by a variety of actors (non-profit associations, local or public institutions) can cope with the needs and requirements of seniors living in the areas under study.

Contemporary societies have recorded an increase in the ageing rate of the population that requires an adjustment of care and assistance for the elderly at different levels: “at the micro level, individuals and families, [but also] at the macro level populations and […] all sub-populations, understood both as groups of particular populations and as populations of individual territorial units […]. [Thus] the consequences of the ageing process are the most varied and involve all aspects of population, society and economy” [1] (Golini, 2005:351-352; Our Translation ).

Therefore, the ageing process characterizing contemporary societies does not exclusively regard the individual dimension, but also the collective one. The nature of this process also leads to questioning and amplifying the concept of active ageing, which is framed by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2002) as “an important strategy to address the social, health and economic challenges of an increasingly long-living population (Walker and Maltby 2012)” [2] (Facchini, 2023:193; Our Translation ). The elderly population indeed represents a fragile category in contemporary societies, leading it to experience social exclusion and even developing a form of ageism and stigma in later life (Barrett and Barbee, 2022). Social exclusion can be described as the disconnection between social actors and groups from the mainstream culture (Commins, 2004; Moffatt and Glasgow, 2009). More in detail, this condition should be seen as a process combining variables, profiles and contexts that may bring social actors and/or groups of individuals to experience such a situation (Alberio et al. , 2022): “regardless of its origins, social exclusion is characterized by at least four common features. Firstly, it is a relative concept […] involves agency , where an act of exclusion is implied (Atkinson 1998). This might involve older individuals being excluded against their will, lacking the agency to achieve integration for themselves, or choosing to exclude themselves from mainstream society. Thirdly, exclusion is dynamic or processual […]. Fourthly, most definitions acknowledge the multidimensionality of exclusion” (Walsh et al ., 2018:83). As highlighted in the literature, the concept of social exclusion is not uniquely defined. It could be seen as and it could also represent a dynamic process: social exclusion can be perceived as a complex, multidimensional and relational process that can lead to negative consequences concerning the individual’s quality of life and well-being (Böhnke and Silver, 2014).

Regarding these aspects, “social exclusion is receiving growing attention within gerontology. Such interests reflect the combination of demographic ageing patterns, ongoing economic instability, and the susceptibility of ageing cohorts to increasing inequalities” (Walsh et al ., 2018:81): elderly social exclusion could be seen as a challenging process involving both the lack or the denial of resources, rights, goods and services in older age and the impossibility to take part in the mainstream society, which affects seniors’ quality of life as well as the cohesion of an ageing society overall (Levitas et al ., 2007 in Walsh et al ., 2018).

Indeed, even if in different and disparate forms, the ageing process could lead to discrimination in access to social life: the environments in which older people live have an important role to fulfil, e.g., “rural environments are cause of concern due to a general lack of public and telecommunication infrastructures […]. On the other hand, they have been indicated as age-friendly environments, being more likely to encompass informal support networks that enhance older people’s social inclusion” (Carlo and Bonifacio, 2021:462). Thus, rural environments might be a source of both social exclusion (lack of transport, infrastructures, etc.) and social inclusion (neighbourhood social relations, family network, etc.).

In the case of Italy, rural areas are often defined as internal areas that according to the Italian Strategy for Inner Areas (SNAI [3] ) are “those areas significantly distant from the centres of supply of essential services (education, health and mobility), rich in important natural and environmental resources and valuable cultural heritage” [4] ( Our Translation ). Although named differently, Canadian rural regions can experience similar phenomena (Alberio, 2018).

In rural areas, both in Canada and Italy, the social exclusion faced by the elderly could be associated with the decline of and the resulting lack of transport inside these areas and have possible negative effects on the elderly population – exclusion from services, amenities and mobility (Walsh et al ., 2018). In this sense, decline and/or the lack of transport could cause the elderly to experience limited conditions of access to services and the consequent inclusion of the latter in the area of reference. Furthermore, alongside these elements, as highlighted in the literature, it is underlined that rural areas suffer from a lack of distribution of health workers and auxiliary services, thereby forcing seniors in some cases to turn to distant services (Koff, 2019). The social exclusion experienced by the elderly in rural areas could also be due to the “lack of activities, interests and stimuli [capable of] accentuating the more problematic aspects of ageing (Havighurst 1963; Rowe and Kahn 1987)” [5] (Facchini, 2023:193; Our Translation ).

The reduction of physical and social contacts limited social participation and even more reduced access to certain services during the pandemic crisis further increased the already high risk of social exclusion for the elderly population group within these territories. Thus, the pandemic crisis may have altered the fragile balance of the rural areas, causing seniors to experience conditions of difficult access to services and consequent social exclusion and may have underlined the effects and the action of globalization that can standardize

“certain experiences of individuals but at the same time amplify the differences between them, especially concerning the capacities and possibilities of facing and managing these same experiences. […]. Whether everyone is exposed to the COVID-19 risk, yet everyone’s possibilities of protecting themselves from this risk and coping with its consequences change”[6] (Caselli, 2020:266; Our Translation).

Nevertheless, rural areas – such as those object of our research –, from a social and territorial point of view, can embody a privileged place to observe, study and analyze social innovation: rural territories can allow both the understanding of the crises that societies go through, by changing their balance, and the identification of innovation practices implemented as a response to crises (Carrosio, 2019).

The other central concept here is the one of social innovation, which is extremely relevant in this perspective: “Innovation is not just an economic mechanism or a technical process. It is above all social phenomenon. […]. By its purpose, its effects, or its methods, innovation is thus intimately involved in the social conditions in which it is produced” (Cresson and Bangemann, 1995 in Cajaiba-Santana, 2014:43). Social innovations can be embodied by new products, services and systems that simultaneously meet social needs and create new social relationships and/or collaborations (Murray et al ., 2010). As the social environment changes and new issues emerge, therefore, social innovation can be understood as the interaction of different actors creating new alliances and collaborations for greater social impact (Alberio, 2023). Therefore, the urban collaborative dimension embodies a fundamental element “for the development of the city, where the participation of individuals provides the basis for the construction of participatory planning systems from below (bottom-up) that are able to best respond to the instances of development and liveability of the territory (Ciaffi, Mela, 2011)” [7] (Viganò and Padua, 2018:49; Our Translation ), highlighting how collaborative urban and local territory management can thus enable to respond “to the need to provide real answers to the needs of local communities in a path of sustainable development” [8] (Viganò and Padua, 2018:56; Our Translation ). In conclusion, it seems relevant to emphasise that,

“the elderly, and with them the very elderly, constitute de facto the most problematic social category and at the same time, by necessity, the greatest resource that institutions will have to manage from the point of view of public policies […]. On the one hand, the expansion of expenditure for health services and the social costs to be dedicated to care and assistance, on the other hand work […] constitute the plates of a scale that will have to be calibrated with extreme care, in order to guarantee social balances”[9] (Sarti, 2008:7; Our Translation).

Indeed, this research’s objective is to identify not only the possible deleterious effects that have accentuated the vulnerability of the elderly but also the protection and support measures that have enabled and are enabling seniors to cope with the pandemic crisis, emphasizing the advantages and disadvantages of their situation in an emergency health context and highlighting the available resources and community dynamics. In fact, the situation created by the health crisis may have disrupted the fragile balance of rural areas, accentuating both the possible difficulties in accessing care and services and the social exclusion of the most vulnerable populations, including the elderly (Balard and Corvol, 2020; Alberio et al ., 2022). The collaborative and community dimension represents

“an attempt at collective governance of the complex matter of urban transformation – especially where re-generation processes are concerned, in which not only the tangible but also the intangible sphere of the territory is subject to modification and pressure – in order to achieve a common result, shared by the widest range of actors involved, and therefore socially sustainable”[10] (Viganò and Padua, 2018:54; Our Translation).

02. Methodology

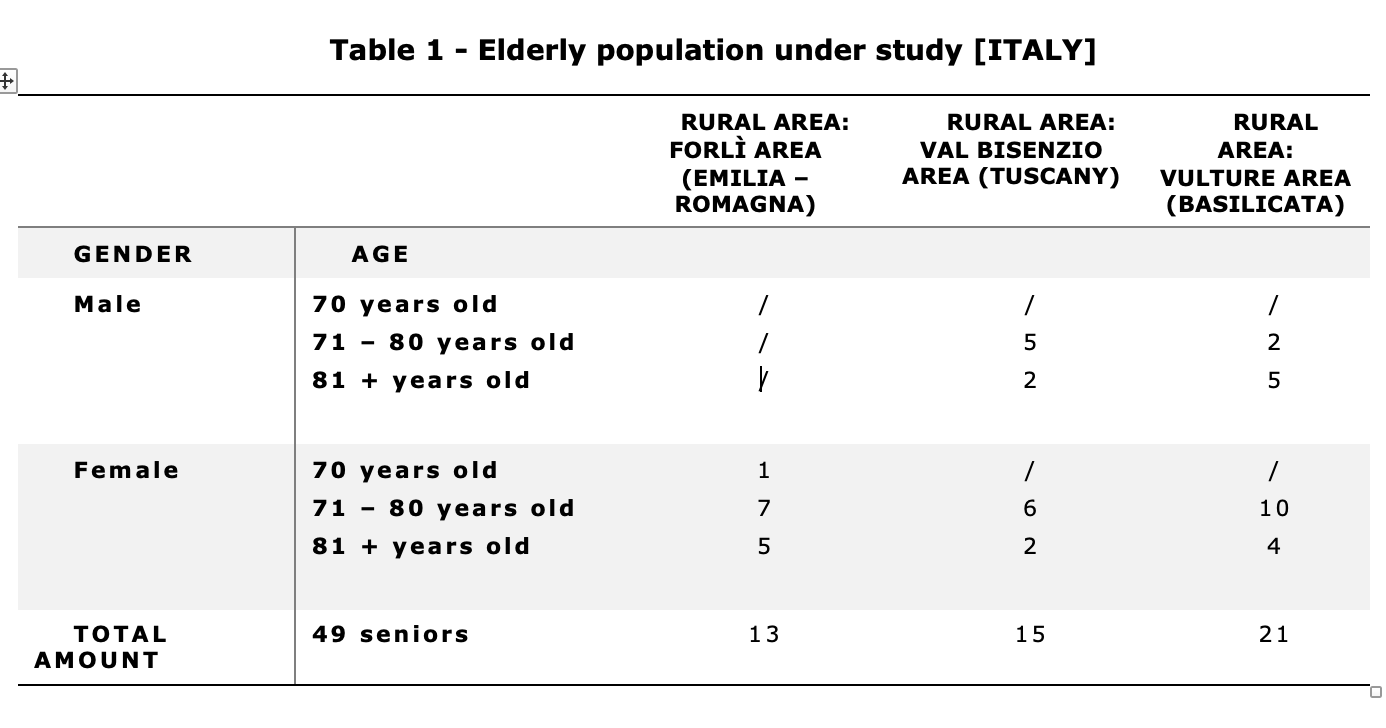

This research is collaborative research whose main objective was to build joint knowledge among the various actors, i.e. seniors, social and health professionals and researchers in order to be able to identify and analyze the dynamics of social exclusion that seniors may have faced in a pandemic situation in territories under study. It has involved rural areas both in Italy and Canada. More in detail, with regard to the Italian territory, three Italian rural areas belonging to different territories were investigated, namely the Forlì area (Emilia – Romagna), the Val Bisenzio area (Tuscany) and the Vulture area (Basilicata). While, with regard to the Canadian territory, three rural administrative regions of eastern Québec were selected (Lower Saint Laurence, Chaudière-Appalaches and Gaspésie-Madeleine Islands) [11] . These are territories that group together municipalities (in some cases, they are unorganized territories that thus form an administrative unit with its own powers) and are distinguished by low density, a large proportion of the population over seventy, geographical, socio-economic and service diversity and mostly distant from the main urban centres.

The objective of our research project was to identify and analyze the dynamics of social exclusion which seniors in the rural areas under investigation may have experienced during the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the possible social and territorial effects of the pandemic on the work and experiences of social and health professionals (social services, care services, community work) in the rural areas. Furthermore, the research aims to question the relevance of local dynamics in coping with the social, material and health needs of the elderly during the pandemic, as well as the challenges this poses in terms of social intervention in rural areas. The reference population consists of both elderly people (seniors seventy years old and over) and social and health professionals (including associative and community actors) to be able to draw a more exhaustive picture with respect to the implementation of initiatives responding to the needs emerging from the crisis.

The semi-structured interview tool was used as it allows the questions in the interview grid to be outlined according to the course of the interaction with the interviewee, facilitating flexible communication. In addition, in the Italian territory, 78 semi-structured interviews were conducted, which were carried out both remotely and in person, and involved 49 elderly people and 33 social and health professionals. While, in the Canadian territory 99 semi-structured interviews were conducted, which were carried out remotely (both by telephone and through the Zoom platform) and which involved 61 older people and 38 stakeholders working in the territorial and socio-political management of ageing and crisis management.

Figure

Figure

The sample was selected by means of snowball sampling, which is useful as it is a particular phenomenon with a reduced accessibility given the availability of a target considered to be a niche, but also a particularly sectoral field of investigation. A major difficulty encountered in the recruitment process is that of accessing the most isolated individuals, who have not been identified by the organizations. This aspect might have led to a representativeness distortion of the participants both within the Italian and the Canadian contexts [12] .

In conclusion, the semi-structured interviews (with an average duration of about one hour) were subsequently transcribed and analyzed through a content analysis: each code that emerged was then linked back to one or more categories (conceptual units) through a classification process. The analysis resulted in codes and categories that were as representative and complete as possible with respect to the data that emerged. This process facilitated the comparative analysis between the two territories.

03. Results and discussion: the condition of the elderly in the Italian and Canadian rural areas between pre-existing and emerging needs

Within contemporary societies, there is an increase in the ageing rate, which requires an adjustment of care and assistance work for the elderly and in certain conditions their acknowledgement as a fragile category of the population: “The progressive ageing and the demographic changes that are affecting our societies impose a serious reflection on the consequences generated and the transformations” [13] (Rossi and Meda, 2010:131; Our Translation ) occurring, also as a consequence of the pandemic health crisis.

In the following sections, our aim is to highlight the different forms of social exclusion with which seniors living (in) rural areas of Italy and Canada have, at certain conditions, to deal with.

Furthermore, a closer consideration will be given to the possible effects that have exacerbated the vulnerability of seniors, as well as the protection and support measures that have enabled and continue to allow them to cope with the health crisis and its long-term consequences, identifying the advantages and disadvantages of their situation before and after the pandemic period, as well as the community dynamics and their possible consequences.

3.1 The needs of the elderly before the pandemic

Rural areas are often defined as those territories that are “united by a negative differential of aggregate opportunities for the population [...], by a lack of services that allow people to fully exercise their rights of citizenship, with a very high variability of morphological, socio-demographic, economic conditions. [...] most of them are in the mountains or hills, they are still depopulating and have mostly an elderly population, employment rates and average incomes are lower than in other municipalities, they experience a worrying situation of abandonment of the territory” [14] (Carrosio, 2019:643; Our Translation ). Therefore, problematic conditions can be experienced in these areas influencing the local population, but also and especially some vulnerable groups, such as the elderly. Inside these areas, the ageing process is characterized by its own individual specificities (Mallon, 2014). Indeed, in these territories, several risk factors of social exclusion may arise for the elderly people living there (Alberio et al ., 2022). Some of these risk determinants depending on the context are, for instance, the lack of services, the lower average income and the high unemployment rate – a condition that has an (in)direct impact on the elderly: a high unemployment rate impacts families who very often find help and depend on their elders (a condition that is present to some extent in the Canadian and especially in the Italian context). These aspects can lead to social exclusion affecting the quality of life of social actors and the cohesion of the wider society through different dimensions: “Old-age exclusion involves interchanges between multi-level risk factors, processes and outcomes. […]. Old-age exclusion leads to inequities in choice and control, resources and relationships, and power and rights in key domains of neighbourhood and community; services, amenities and mobility; material and financial resources; social relations; socio-cultural aspects of society; and civic participation” (Walsh et al ., 2018:93).

Firstly, both in the Italian and Canadian contexts, most of the population of reference experienced a feeling and some forms of social disregard – a perception of loneliness (Feng, 2012) and/or a kind of symbolic exclusion (Guberman and Lavoie, 2004); feelings that lead individuals and societies more in general to feel fear and dread towards ageing itself ( ageism ):

“The retired no longer participates in the active world. They [us, ndr] no longer participate in anything. I really do not know” (Elderly, female, 81+ years old, Basques)

It is further added that:

“As seniors, we would like to be approached more often. That is fun to say. It’s that one feels a bit excluded. We feel excluded. The elderly is not for our purposes [is not for our society, ndr]. So, we leave him out. That is what’s hard to accept” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Bellechasse)

In the Italian context, similar elements emerge with regard to ageing and the consequences it can bring, emphasizing how:

“The first thing that comes to my mind [when thinking about ageing, ndr] is to be alone [...]. I try not to think about it” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

More in detail, most of the population of reference often report how elderly people are not valued and/or there are certain negative representations or constructions of ageing in society ( ageism ):

“[the senior, ndr] is not loved […] by the young people is often seen a bit sideways […] by the society in general the elderly person is not worth much” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Forlì area)

However, while both the Italian and Canadian territories reveal this symbolic dimension of exclusion, two main differences must be emphasized. On the one hand, within the Canadian context, a considerable emphasis is placed by the elderlies themselves on the economic precariousness that they would experience – economic exclusion (Guberman and Lavoie, 2004) or exclusion from material and financial resources (Walsh et al ., 2018). Although most of the elderly interviewed are satisfied with the living environment and the home in which they live, they underline that the decrease in income available – mainly due to leaving the labour market and the consequent retirement salary – is an obstacle in maintaining certain conditions of good living. For example, some of the seniors underline how rent prices have risen, something that might contrast with the idea that the housing market is always affordable in rural areas:

“For the elderly it is a matter of income. First of all, rents have become very expensive […] some people who pay a very high rent, do not have enough money to eat” (Elderly, male, 81+ years old, Basques)

Therefore, the economic precariousness that the elderly may experience could damage and affect their mental health condition (Alberio and Plachesi, 2024). The difficulty in sustaining the financial costs for the maintenance of their housing could also have consequences on their housing-hygienic condition. The fragility associated with advancing age also leads, for example, to a condition of fatigue and loss of energy that can inhibit the ability of the elderly to take care of their living environment:

“The house is a bother [for me, ndr] when it is dirty. I leave things lying around because I struggle to pick them up and then [the house, ndr] gets dirty quickly” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Haute-Gaspésie)

However, the lack of help with household duties (the hours provided by public institutions are very few and available just to those who respect severe criteria) and the economic difficulty of obtaining such support in the private market are elements of concern for the elderly we interviewed:

“To get the help I need I should get more money [from the retirement, ndr] to do the housework, to cook the food, to do this and to do that” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Kamouraska)

And again:

“People invest less, there is not enough housing for the elderly, for families […] because it is a question of income for the elderly” (Elderly, male, 81+ years old, Basques)

Therefore, in some situations, the economic precariousness experienced by the elderly and the possible lack of institutional support may affect the individual well-being of seniors, who, in the absence of their own independence and access to services, may consider relocating to a residence for the elderly – often far from their home area – in order to take advantage of more services (Colin and Coutton, 2000).

The fact that this dimension of economic precariousness appears less in the Italian context might in part at least depend on cultural values and family relations. Without implying that these are not present in Canada, the Italian model of welfare is mainly the so-called “ familistic model ”. This model is characterized by a quiet level of “ familiarisation ” of care and intervention: “The shape of the Italian welfare state has been deeply influenced by assumptions about the family and its gender and intergenerational responsibilities: the family is both an economic unit in which there are dependents (e.g., children, wives, parents, and disabled adults) and “family heads” who redistribute income, and a caregiving unit in which there are also dependents and those (i.e., women, wives, and adult daughters) who “redistribute” care” (Saraceno, 1994:60).

On the other hand, analyzing the Italian territory, there is another aspect emerging: some of the elderly under study emphasize a substantial gender difference with respect to ageing and social activities. For example, some research participants pointed out that:

“For women it’s more difficult in my opinion, men have the social clubs and play cards, which have always brought them together, but for women there are no activities […] there is no meeting place, there are none […] many are reduced to being housewives, to staying indoors, doing their knitting, doing their chores and that’s it […] for men it’s different, but not for women, even for young people there is nothing [here, ndr]” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

Therefore, elderly social exclusion could be seen as a challenging process including the impossibility of taking part in mainstream society, affecting seniors’ quality of life as well as the cohesion of an ageing society overall (Levitas et al ., 2007 in Walsh et al ., 2018). More in detail, within the territories under investigation, the majority of the population under study underlines – though through different variables and dimensions (economic exclusion, for example, in the Canadian territory) – a common feeling of social exclusion, underling how these aspects pre-existed the advent of the pandemic.

First and foremost, it should be emphasized that rural areas are places and territories where a strong system of transportation network may be lacking. The decline and consequent lack of transport can cause negative effects that can weigh upon the local population, but also in particular on the elderly, restricting access to services and, consequently, the social inclusion of the seniors within the community. For example, rural communities, as evidenced within the literature, experience a lack of distribution of health care providers and auxiliary services, which in some cases forces seniors to turn to distant services (Koff, 2019). In addition, settlement within isolated areas – such as rural areas – and the lack of suitable resources may also encumber the well-being of seniors as well as constrain their participation in social interaction (Zaidi, 2011; Scharf et al ., 2005), leading to exclusion from basic services (Kneale, 2012) and/or difficulties in accessing to services (Walsh et al ., 2012). Within the areas under study, both in Italy and Canada, there is a chronic difficulty in accessing services:

“There is no post office, there is no general shop, services are decreasing, you have to go to the next town or place, which is a bit far away. If people have problems moving, it is a different story [and, ndr] it is up to the family to try to intervene [although, ndr] it is not necessarily the case that the family stays there [nearby, ndr]” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Bellechasse)

And also is added:

“There’s nothing left in *** [name of the specific area, ndr], there is no bank, the post office is open one day on, one day off, it is a tragedy here” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Forlì area)

Despite the lack of services, however, rural areas are characterized by a strong cohesion net (Bioteau, 2018) supporting the elderly. For instance, in rural areas, the family plays and has played a central role in supporting the elderly. Indeed, the family network provides support for the elderly based on reciprocity (Attias-Donfut, 2000) and obligation (Pin, 2005). Family care is mainly characterized by two aspects: “One refers […] to the expectations of loyalty and gratuitousness within its key relationships, between the sexes and generations […]; the other […] to the concrete supportive and sustaining action it performs within the family unit towards one of its members to cope with any specific problems” [15] (Rossi and Meda, 2010:116; Our Translation ). Furthermore, the territorial network in rural areas is characterized not exclusively by a family basis of support for the elderly, but also by the network proximity that often distinguishes these areas from urban centres. As an example, these realities present a strong network and neighbourhood proximity, as is highlighted in the Italian and Canadian territories during the research:

“I have to say that living in a rural environment allows you to live and experience life to the fullest, you can meet as many people as possible on the street […] in the sense that there are fewer people, but when neighbours are around you can have a chat, whereas in the city you can’t” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Bas-Saint-Laurent)

This is also true in the case of Italy. As some participants in the Italian contexts reported:

“We all know each other a little […] it is not like in the city where you might go out, someone would try to stay away from you […] here I don’t experience this feeling of being excluded, pushed away” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

These are fundamental aspects that have led the majority of the population under study to prefer the rurality of the areas where they live to the city. In fact, it is emphasized that “the city is much more anonymous […] I still prefer to live here despite the inconvenience of the services, which are not there like in a big city” ( Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area ).

Alongside these changes, as the next section will show, it is important to pay attention to the changes – or lack – that the pandemic health crisis has brought with it, highlighting the possible emergence of new needs and requirements on the part of the elderly population and the consequent measures put in place to counter both old and new needs of the elderly within rural areas.

3.2 The arrival of the pandemic and the additional needs

In the previous section, several pre-pandemic needs of the elderly emerged. During the health crisis, different measures were taken which led to different consequences: the reduction of physical and social contacts limited social participation and access to certain services, thus increasing the already high risk of social exclusion for the elderly population within these territories. Therefore, the emergence of these conditions during the pandemic crisis may have disrupted the fragile balance of rural areas, causing the elderly to experience hard access to services and consequent social exclusion. Hence, as previously discussed, ageing brings with it various aspects of exclusion, social isolation and discrimination in access to social life – especially in terms of access to services. Such aspects, if placed within the advent of the pandemic crisis, can lead to a greater fragility of the rural areas. Indeed, with the advent of the pandemic, not only do difficulties in accessing services and health care increase, but social contacts and participation of the elderly are also restricted, thus increasing the risk of isolation (Balard and Corvol, 2020; Alberio et al ., 2022).

During the pandemic period, specific measures were implemented to protect the elderly, who were among those most at risk; measures which, however, had very important repercussions on access to basic services and contacts. The limited access to health and social services may therefore induce the elderly in rural areas to face greater exclusion. As seen in the previous sections, rural areas are characterized by their difficulties in accessing services and a weak transportation infrastructure:

“There is a lack of that network of specific services for the elderly. […] this support network is missing so that the elderly can then be autonomous, self-sufficient for a long time” (Social and health professional, Vulture area)

This aspect persisted and increased during the pandemic period among the study population. Indeed, some elderly people reported that there was a limited availability of public services during the pandemic period: some elderly people found it difficult to maintain access to types of health care:

“I don’t know if the doctor didn’t want to meet me or if he was afraid of Covid, I don’t know […] when I later managed to get an appointment, I didn’t see the doctor, but the nurse!” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Bellechasse)

Access to services and care improves the living conditions of the population, especially the elderly (Alberio et al ., 2022). The lack of access to these elements could, at least in part, lead to the depopulation of rural areas. However, as highlighted above, the restrictive measures that were implemented during the pandemic period in order to protect the elderly population had important repercussions not only on access to services and care but also on the condition and mental health of the elderly.

Indeed, the effects of the pandemic on the elderly population also depended on how they experienced and dealt with anxiety and fears. The measures taken during the pandemic period with the aim of preserving the elderly and containing Covid-19 infection as much as possible weighed on the social and psychological well-being of the elderly, resulting in additional problems with which they had to cope. The measures implemented during the pandemic period caused the majority of the elderly population under study various problems, in a sense accelerating ageing through, for instance, inactivity or physical and social isolation of seniors:

“Covid in other words did not advantage us mentally in all things, it did not advantage us and I think it has helped few at least us of this age” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

Furthermore, it is often reported that the pandemic has taken a heavy toll on the mental condition of the elderly who have had to cope with loneliness, stress and anxiety:

“In the beginning […] I did not go anywhere […] even today, if I have to go to the grocery shop, I am one of the first […] I enter the shop for 10 or 15 minutes maximum, then I go out again [for fear of being infected, ndr]. Then I go back home” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Bonaventure)

Some of the professionals who took part in the research underline how:

“We are experiencing that panic attacks, which usually happen to young people, very young people and adults, are lately affecting the elderly as well, and it is not dementia […] this is something new that until a few years ago I had never collected among the deposited elements, here elderly people in a very compromised state of health keep coming” (Social and health professional, Forlì area)

These aspects and consequences caused the social exclusion of the elderly to become more pronounced since the pandemic period. Therefore, the health crisis thus seems to have made the sociopsychological vulnerabilities of the elderly more visible, demanding a solution capable of providing useful and necessary services to the elderly. Primarily, the protective measures addressed to the elderly during the pandemic period had repercussions on access to primary services and contacts, thus leading to the emergence of additional problems with which the elderly were confronted (mental health, anxiety, depression). Within the studied territories, home services were activated to respond to the needs of seniors during the health crisis. There are differences in this measure in the territories investigated: in the Canadian context, the service is mainly provided by community groups and volunteers, while in the Italian context, it is shown how there was not only a local but also an administrative institutional response. This is connected to the different institutional forms between the two countries and the still different roles between municipalities in Italy and Canada. Indeed, within the Canadian context, it is highlighted not only how the services are mainly centred on community groups (supported and financed by the state province), but also how these groups in rural areas are often managed by senior volunteers. In addition, during the research, several seniors have emphasized how during the pandemic the volunteer committees would have helped only through phone calls:

“Our volunteer committees just called, instead of making visits they called the people they were used to seeing [...]. The visits had become calls” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Bonaventure)

However, on the other hand, inside the Italian territory, most of the seniors who took part in the research underline how there was a local institutional response in the realities in which they find themselves, emphasizing the strong domiciliation of services:

“[...] all the over seventies could not go out to do their groceries [so, ndr] they would phone the greengrocer […] they would bring us the groceries at home […] the greengrocer has remained that even now you call her and she comes, you tell us by phone, you send an email, she reads or you call her, she prepares them and brings them to you” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Vulture area)

Throughout the literature, it is emphasized that the use of digital technology has played “a primary role both in enabling the continuation of most professional activities and in making confinement more bearable due to the possibility of information and entertainment it offers […]. Social networks and devices have been essential in nurturing horizontal communication between citizens” [16] (Turina, 2021:624-625; Our Translation ).

During the pandemic period, both within the Italian and Canadian contexts, activities were interrupted, and consequently the relationships of the elderly; relationships which, while in normal times were expressed with casualness and exchanges mainly through neighbourhood and family networks, during the health crisis underwent a strong change. To this extent, it could be said that relationships have been rethought, especially through the use of alternative devices, such as smartphones and computers. Thus, the use of technology for the elderly population could embody a means not only to preserve their autonomy but also to establish their presence in the present (Klein, 2019). In fact, the social bonds involving elderly population have been significantly reconfigured at the time of the pandemic: although physical contact and face-to-face community activities have decreased, links between peers and with their family network are maintained through the use of technology that can help overcome isolation and loneliness as well as maintain a sense of belonging (Wang et al ., 2022). Indeed,

“Luckily […] I use the computer, the mobile phone properly so having the applications in direct contact with the administration like so many other things, like the bank, so I was […] constantly informed about situations, new changes and also about protective provisions” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

However, the use of technological devices may lead to greater social inequality and exclusion of older people who find themselves conversing with tools they are unfamiliar with which may make requests and access to services even more difficult. Moreover, for some elderly people, the use of technological devices does not represent a meaningful alternative to face-to-face relationships only:

“My biggest problem is not visiting my relatives outside because I have my friends outside that I would like to see, I have my sister that I get along with [...] during the pandemic I was here. [...]. Telephoning everyone we do, virtually can also be the same thing, but in person, not being able to visit the people you love makes us a bit nostalgic” (Elderly, female, 81+ years old, Kamouraska)

However, technological support during the pandemic period was crucial within the investigated territories as it made possible access to certain services and the containment of exclusion that the elderly may have been confronted with.

Therefore, the elderly who have not and cannot take advantage of new technologies face new forms of exclusion.

In conclusion, with regard to what has emerged so far, it must be emphasized how extremely important it is to “pose the problem of the liveability of places on the margins, building new welfare systems that respond in new ways to the needs of those who already inhabit and those who might re-inhabit [these places]” [17] (Carrosio, 2019:643; Our Translation ). Furthermore, it could be remarked how “isolation served as a magnifying glass for social inequalities” (Morin, 2020:29) and how, therefore, the pandemic has accentuated dynamics already present before the pandemic period, affecting above all the most fragile sectors of the population (Capanema-Alvares et al ., 2021), such as the elderly.

At this point, it is relevant to question and investigate – as attempts will be made in the following section – the solutions that have been put in place to cope with the emergence of new problems and the affirmation of old ones. For instance, the pandemic crisis could be understood as an accelerator of the dematerialization of social relations (Wang et al ., 2022) that could have helped organizations’ work. In fact, questioning the support and resources offered at the local level (Pihet and Viriot-Durandal, 2009) of local authorities and institutions has become important, especially in the post-pandemic crisis period.

04. What governance for ageing at a local level?

The preceding sections underline how in the territories studied the needs and requirements of the elderly actually preexisted the pandemic crisis, which accentuated the deleterious effects of the difficulties in accessing care and services that are central to crisis management. As a matter of fact, the pandemic period revealed several challenges that the elderly had to face: restrictive measures that changed their lifestyle and accentuated the condition of social exclusion they might experience. This condition has also altered the fragile balance of rural areas resulting in increased social exclusion and marginalisation of the most vulnerable populations, including the elderly who have found themselves disoriented:

“At some point we had instructions that perhaps should not have been adopted for our region because there were no cases [of Covid infection, ndr] and we had the same instructions as the big cities” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Bonaventure)

Social isolation – as seen in the previous sections – can be attributable to different elements that characterize rural areas such as those investigated in the research, i.e., access to services and care, economic security and the use of technology that can lead to exclusion from services, amenities and mobility (Walsh et al ., 2018) or to economic exclusion (Guberman and Lavoie, 2004). These aspects can lead to a lack of not only physical, and psychological but also social well-being in the life trajectories of the elderly population – such as the onset of anxiety and stress. Thus, it is of extreme relevance to question not only the factors and risks of social exclusion but also the strategies and measures put in place to successfully counter these phenomena. Therefore, it is important to question the solutions that have been put in place to deal with pre-existing and emerging problems since the difficulties of ageing and its consequences might also be due to government policies that do not or only partially reflect the needs and requirements of the elderly (Koff, 2019).

Primarily, in the studied territories, most of the elderly population under study emphasize a strong need to reorganize work and social intervention within the internal areas is underlined as a response: there is a specific need from the elderly, both in the Italian and in the Canadian territory, to implement new practices and new models of action. In fact:

“Institutions [in thinking about and addressing seniors, ndr] are a bit lacking here” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

Further on, it is specified how:

“Our municipal authorities here do not seem to have been so bright […] in general it seems to me that we have been a bit abandoned by the institutions both at regional and Italian level, and at local level. There has not been much in the way of initiatives, or that I know the information on the management of the pandemic was limited to say even the information of putting a bulletin once a week on Facebook” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Val Bisenzio area)

Especially highlighting, both in Canada and Italy, how responses have been lacking, especially in terms of health:

“Doctors no longer made appointments […] [but, ndr] made appointments over the phone because [for example, ndr] the consultation with my doctor I made over the phone” (Elderly, male, 71 – 80 years old, Gaspésie-Îles-de-la-Madeleine)

And so on:

“In my opinion yes, not much was done, some people, [the elderly, ndr] were treated badly even in hospitals [and later it’s added, ndr] it [this aspect, ndr] got worse with the pandemic because I saw people dying in loneliness, a brother-in-law of my husband dying in hospital of loneliness because his wife could not visit him” (Elderly, female, 71 – 80 years old, Forlì area)

However, this difficulty could be attributed to the fact that the administrations’ responses also depended on ever new and ever different directives:

“We received e-mails every morning. The problem was that things were constantly changing from one day to the next […] by the time we started to use the new measures, to apply the instructions, the health department had already changed them” (Social and health professional, Chaudière-Appalaches)

In this way, responding with a reorganization of work was extremely difficult due to different elements. For example, on one hand – as seen above –, administrations responses depended and waited for instructions and, on the other hand, they had to learn to dialogue with new tools. As highlighted:

“We had more work, much more work. What was different was that some organizations close to us shut down for different reasons […] they changed to remote work and this made services more complex” (Social and health professional, Chaudière-Appalaches)

In fact, it is underlined that there was a reorganization of work through different aspects. For example, it is emphasized by some social and health professionals how important the use of technology was and still is:

“We are still working in this way [telephonically, ndr] because it allows us to contact many more people at more elastic hour […] socially we tried to hold on to everything we had and also with technology […] that allowed me thing” (Social and health professional, Forlì area)

More in detail, in both the Italian and Canadian territories under study, institutions took advantage of certain elements specific to rural areas to be able to respond to the care needs of the elderly. Thus, for instance, as a response to the needs and demands of the elderly, the social connections and territorial cohesion that characterise these territories have been promoted: a network of proximity not only with the administrative part of the territory, but also with the local and relational part, thereby establishing a solid constellation of relations (Alberio, 2023) not only family, but also neighbourhood relations that took place during the pandemic period were fundamental elements of response:

“We have the luck of having very good relations with administrations and other associations, so for now, any requests for realization of initiatives, as soon as the request is made to the municipality, are always realized without problems” (Social and Health Professional, Val Bisenzio area)

In addition to these findings, it should be emphasized that rural areas have been affected since the twentieth century through processes of abandonment, depopulation and a crisis in the economic fabric (Osti, 2016). The result of these processes necessarily leads to an urgency – economic, social, demographic, etc. – of response that can be embodied in eco-sited practices, i.e. strategies capable of holding together both the production of goods and the provision of services (Farinella and Podda, 2020). Although there are fewer and fewer economic and social provisions for the design of services, it can be seen that network proximity and the role of the public actor are essential elements for their success (Ascoli and Pavolini, 2012; Andreotti and Mingione, 2014). However, as evidenced within the literature, there has been a shift from the hierarchical, paternalistic and welfare state to a network welfare able to generate social cohesion. As regards the realities of the research, it is noted that within the Italian territory the presence of a “synergy of all the realities present, really there was a collaboration of administrators” ( Social and health professional, Vulture area ).

And also:

“Within the crisis management cell there are partners, including, for example, the RCM with whom I became close; I had never worked with our RCM director, but meeting new people on a regular basis has created links and helped solve problems in other cases” (Social and health professional, Basques)

On the other hand, within the Canadian context, community organizations, i.e. voluntary activities in the field of health, and social and neighbourhood services, play an important role: these are sources of solidarity that are useful for improving the living conditions of the population, especially the elderly.

Therefore, if, on one side, the territories have to mobilize themselves autonomously to be able to satisfy their needs – which implies a redefinition of the role of the State – on the other, there is a lack of public administration regarding the economic and institutional resources needed to create favourable conditions for the autonomous action of local social actors (Giry, 2020). Hence, if the mobilization of local and community organizations has made possible and allows some of the difficulties faced by the elderly to be circumvented, on the other hand, the criticality of the reality under consideration tends to increase the condition of dependence of the elderly on community resources that are able to offer – at least in part – support services.

It also seems crucial to reconsider “in terms of mutual cooperation with multiple social, economic, political and cultural effects. The objective is to create a context capable of increasing the common resources necessary for the work of all the actors involved (Magnaghi 2020)” (Macchioni and Prandini, 2022:364), so that the needs and requirements of seniors can be met through governance capable of generating community and social cohesion (Messina, 2019).

In conclusion, the advent of the pandemic crisis has brought to the agenda the necessity of a reorganization of work and social intervention within the rural areas – perhaps capable of responding not only to the needs of seniors living in these kinds of areas merging in the last 20 years due to the demographic changes, but also to the new needs resulting from the pandemic health crisis.

05. Conclusions

As we underlined the aim of this research was to analyze the situations and the experiences of the elderly (aged seventy and over) in the rural areas, both in Italian and Canadian territories, highlighting the socio-territorial effects that this health crisis has had on seniors. Indeed, the situation of the health crisis may have disrupted the fragile balance of rural areas, accentuating both the possible difficulties in accessing care and services and the social exclusion and marginalization itself of the most vulnerable populations, in our specific case the elderly (Balard and Corvol, 2020; Alberio et al ., 2022).

It is important to underline that the situations and the needs of the elderly are crucial to understanding the ageing process which involves not only individuals and families but also at a more macro level: different territories, populations and institutions. Indeed, the aging process involves in itself populations, society and the economy’s aspects (Golini, 2005).

As stated above, we questioned the situations and needs of older people living in rural areas. Especially since in rural areas, the social exclusion faced by the elderly could be associated with decline and the resulting lack of transport inside these areas and the possible negative effects on the elderly population. In this sense, decline and/or the lack of transport could cause the elderly to experience even more limited conditions of access to services and a consequent lack of inclusion at the spatial territorial level.

Furthermore, alongside these elements, as highlighted in the literature, rural areas suffer from a lack of distribution of health workers and auxiliary services, thereby forcing seniors in some cases to turn to non-in presence services or to travel to receive them (Koff, 2019).

All of these aspects – which emerged from our research – are key to understanding but also questioning the measures that have been put in place and are being implemented to cope with the emergence of new problems and the assertion of old ones – especially following the pandemic crisis.

In both territories under study –Italy and Canada – it emerges how in these areas both pre-existing and emerging problems have dialogued. We also questioned whether and which new models of intervention have been developed in the local contexts in order to respond to new and old needs during the pandemic period. Our research also shows how the solutions proposed and implemented often come from local civil society “as a spontaneous response to the constant backwardness of the public in the management of welfare systems, particularly in the most rural and remote areas” [18] (Farinella and Podda, 2020:12; Our Translation ). Solutions and practices thus need not only a unified vision but also a rural development perspective (Barca et al ., 2014). Something which is true in both Italy and Canada, since both countries lack a real model of rural development (Alberio, 2022).

06. Author’s note

This research has been possible thanks to different actors (population at study, health and social professionals, decisions makers, researchers and collaborators, etc.) that have taken part and contributed to this study. We would like to thank all of them. In particular, referring to the Italian context, a thanks goes to: Annalisa Plava, Elisa Castellaccio and Alessandra Tamburriello, who were engaged and actively contributed to the research at different stages. Regarding the Canadian field, we thank everyone involved in this study, in particular: Mahée Gilbert-Ouimet, Nicole Ouellet, Cécile Van de Velde, Majella Simard, Joel Akoї Sovogui, Emanuele Lucia and Sylvie Côté. Manon Labarchède and Mame Salah Mbave worked as post-doctoral fellows and did most of the interviews in Canada. We also thank the Fond de recherche du Québec and all the Ministries involved in the “action concertée sur le viellissement et l’exclusion” that financed part of this research.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

“a livello micro, gli individui e le famiglie, [ma anche] a livello macro le popolazioni e […] tutte le sottopopolazioni, intese tanto come gruppi di particolari di popolazioni, quanto come popolazioni di singole unità territoriali […]. [Dunque] Le conseguenze del processo di invecchiamento sono le più varie e coinvolgono tutti gli aspetti della popolazione, della società e dell’economia” (Golini, 2005:351-352).

-

[2]

“un’importante strategia per affrontare le sfide sociali, sanitarie ed economiche di una popolazione sempre più longeva (Walker e Maltby 2012)” (Facchini, 2023:193).

-

[3]

Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne.

-

[4]

“quelle aree significativamente distanti dai centri di offerta di servizi essenziali (di istruzione, salute e mobilità), ricche di importanti risorse naturali e ambientali e di patrimonio cultura di pregio”.

-

[5]

“venir meno di attività, interessi e stimoli [in grado di] accentuare gli aspetti più problematici dell’invecchiamento (Havighurst 1963; Rowe e Kahn 1987)” (Facchini, 2023:193).

-

[6]

“alcune esperienze degli individui ma al tempo stesso amplifica[re] le differenze tra gli stessi, in particolar modo con riferimento alle capacità e alle possibilità di affrontare e gestire queste medesime esperienze. […]. Se tutti siano esposti al rischio Covid-19, cambiano tuttavia le possibilità di ognuno di proteggersi da tale rischio e di affrontarne le conseguenze” (Caselli, 2020:266).

-

[7]

“per lo sviluppo della città, laddove la partecipazione degli individui fornisce la base per la costruzione di sistemi partecipati di pianificazione dal basso (bottom-up) in grado di rispondere al meglio alle istanze di sviluppo e vivibilità del territorio (Ciaffi, Mela, 2011)” (Viganò and Padua, 2018:49).

-

[8]

“alla necessità di fornire risposte reali alle esigenze delle comunità locali in un percorso di sviluppo sostenibile” (Viganò and Padua, 2018:56).

-

[9]

“gli anziani, e con loro i grandi anziani, costituiscono de facto la categoria sociale più problematica e allo stesso tempo, per forza di cose, la più grande risorsa che le istituzioni dovranno gestire dal punto di vista delle politiche pubbliche […]. Da un lato l’espansione delle spese per i servizi sanitari e i costi sociali da dedicare alla cura e all’assistenza, dall’altro il lavoro […] costituiscono i piatti di una bilancia che dovrà essere calibrata con estrema attenzione, al fine di garantire gli equilibri sociali” (Sarti, 2008:7).

-

[10]

“un tentativo di governance collettiva della complessa materia della trasformazione urbana – soprattutto laddove si tratta di processi di ri-generazione in cui sono sottoposte a modificazione e pressioni non solo la sfera tangibile ma anche quella intangibile del territorio – al fine di raggiungere un risultato comune, condiviso dalla più ampia fascia di attori coinvolti, e quindi socialmente sostenibile” (Viganò and Padua, 2018:54).

-

[11]

In addition, with regard to the Canadian territory, it is specified that two regional counties were selected for each territory: les Basques, Kamouraska, Bellechasse, les Etchemins, Bonaventure and Haute-Gaspésie.

-

[12]

The research methodology also incorporated a quantitative component for the Canadian contexts only, based on a probabilistic survey handed out to seniors (aged seventy years old and over). This survey was mainly used to assess the entity of psychological distress, stress and social exclusion perceived by the elderly during the pandemic. Additionally, the survey enabled the seniors to indicate their intention to participate in the research. However, it has to be specified that only qualitative data will be used and analysed within this article.

-

[13]

“il progressivo invecchiamento e i cambiamenti demografici che stanno investendo le nostre società impongono una seria riflessione sulle conseguenze generate e sulle trasformazioni” (Rossi and Meda, 2010:131).

-

[14]

“accomunata da un differenziale negativo di opportunità aggregate per la popolazione […], da una carenza di servizi che consentano alle persone di esercitare appieno i propri diritti di cittadinanza, con una variabilità molto alta di condizioni morfologiche, sociodemografiche, economiche. […] la maggior parte si trova in montagna o in collina, si stanno ancora spopolando e hanno per lo più una popolazione anziana, i tassi di occupazione e i redditi medi sono più bassi rispetto agli altri Comuni, vivono una preoccupante situazione di abbandono del territorio” (Carrosio, 2019:643).

-

[15]

“l’una rimanda […] alle aspettative di lealtà e di gratuità nell’ambito delle sue relazioni chiave, tra i sessi e le generazioni […]; l’altra […] alla concreta azione di sostegno e di supporto che svolge all’interno del nucleo familiare nei confronti di uno dei suoi membri per far fronte a eventuali specifici problemi” (Rossi and Meda, 2010:116).

-

[16]

“un ruolo primario sia nel permettere il proseguimento di molte attività lavorative, sia nel rendere più sopportabile il confinamento grazie alla possibilità di informazione e intrattenimento che offre […]. Reti sociali e dispositivi elettronici sono stati essenziali nell’alimentare una comunicazione orizzontale tra cittadini” (Turina, 2021:624-625).

-

[17]

“porci il problema della vivibilità dei luoghi ai margini, costruendo nuovi sistemi di welfare che rispondano in modo nuovo ai bisogni di chi già abita e di chi potrebbe ri-abitare [questi luoghi]” (Carrosio, 2019:643).

-

[18]

“come una risposta spontanea al costante arretramento del pubblico nella gestione dei sistemi di welfare in particolare nelle zone più rurali e remote” (Farinella e Podda, 2020:12).

Bibliography

- Alberio, Marco (2018). Supporting carers in a remote region of Quebec, Canada: how much space for social innovation? International Journal of Care and Caring , Vol. 2, n°2, pp. 197-214. https://doi.org/10.1332/239788218X15269112664973 .

- Alberio, Marco and Klein, Juan-Luis (2022). Multi-actor and participative socio-territorial development: Toward a new model of intervention?, The Journal of Rural and Community Development , Vol. 17, n°2, pp. 1-23.

- Alberio, Marco, Labarchède, Manon and Mbaye Mame Salah (2022). Les territoires ruraux de l’est du Québec à l’épreuve de la Covid19. Marginalisation et exclusion sociales des personnes aînées?, Revue Crises et Société, Vol. 1, pp. 1-29. https://www.crisesetsociete.com .

- Alberio, Marco and Soubirou, Marina (2022). How can a cooperative-based organization of indigenous fisheries foster the resilience to global changes? Lessons learned by coastal communities in eastern Québec. Environmental Policy and Governance , Vol. 32, n°6, pp. 546-559.

- Alberio, Marco (2023). L’innovazione sociale tra iniziative “dal basso” e politiche sociali. Qualche riflessione critica su un concetto spesso (ab)usato, In Claudia Golino and Alessandro Martelli (a cura di) (2023), Un modello sociale europeo? Itinerari dei diritti di welfare tra dimensione europea e nazionale, Milano, FrancoAngeli.

- Alberio, Marco and Plachesi, Rebecca (2024). L’innovazione socio-territoriale in un contesto di crisi sanitaria. Il caso studio dell’assistenza agli anziani in tre aree interne italiane in Ganugi, Giulia, Prandini, Riccardo and Ecchia, Giulio. Ecosistemi di innovazione sociale. In Press.

- Andreotti, Alberta and Mingione, Enzo (2014). Local welfare systems in Europe and the economic crisis. European Urban and Regional Studies , Vol. 23, n°3, pp. 1-15.

- Ascoli, Ugo and Pavolini, Emmanuele (2012). Ombre rosse. Il sistema di welfare italiano dopo venti anni di riforme. Stato e mercato , Vol. 32, n°3, pp. 429-464. DOI: 10.1425/38645.

- Attias-Donfut, Claudine (2000). Rapports de générations. Transferts intrafamiliaux et dynamique macrosociale. Revue française de sociologie, Vol. 41, pp. 643-684.

- Attias-Donfut, Claudine (2013). Actions intergénérationnelles et développement durable en milieu rura. Gérontologie et société, Vol. 36, n°146, pp. 117-129.

- Balard, Frédéric and Corvol, Aline (2020). Covid et personnes âgées: liaisons dangereuses. Gérontologie et société, Vol. 42, n°162, pp. 9-14.

- Barca, Fabrizio, Casavola, Paola and Lucatelli, Sabrina (2014) (a cura di). A Strategy for inner areas in Italy: Definition, objectives, tools and governance, Materiali Uval, n°31.

- Barrett, Anne E. and Barbee, Harry (2022). The subjective life course framework: Integrating life course sociology with gerontological perspectives on subjective aging. Advances in Life Course Research, Vol. 51, 100448.

- Bioteau, Emmanuel (2018). Constructions Spatiales des Solidarités. Contribution à une géographie des solidarités, Mémoire d’habilitation à diriger des recherches, Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université d’Angers.

- Böhnke, Petra and Silver, Hilary (2014). Social exclusion, in Michalos, A.C. (ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research, Dordrecht, Springer, pp.6064-6069.

- Capanema-Alvares, Lucia, Cognetti, Francesca and Ranzini, Alice (2021). Spatial (in)justice in pandemic times: bottom-up mobilizations in dialogue. Territorio , Vol. 97, pp. 77-84.

- Carlo, Simone and Bonifacio, Francesco (2021). Ageing in rural Italy through digital media. Health and everyday life. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia (ISSN 0486-0349), Vol. 2(aprile-giugno), pp. 459-486. DOI: 10.1423/101852.

- Carrosio, Giovanni (2019). Italia sostenibile: riconnettere le aree interne. Aggiornamenti Sociali, ottobre, pp. 640-650.

- Caselli, Marco (2020). Uniti e divisi: la pandemia come prova della globalizzazione e delle sue ambivalenze. SocietàMutamentoPolitica, Volo. 11, n°21, pp. 265-269.

- Colin, Christel and Coutton, Vincent (2000). Le nombre de personnes âgées dépendantes d’après l’enquête Handicaps-incapacités-dépendance. Etudes et résultats, n°94.

- Commins, Patrick (2004). Poverty and social exclusion in rural areas: characteristics, processes and research issues. Social Rural , Vol. 44, n°1, pp. 60-75.

- Cresson, Edith and Bangemann, Martin (1995). Green Paper on innovation, European Commission in Giovany Cajaiba-Santana. (2014). Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , Vol. 82, pp. 42-51.

- Facchini, Carla (2023). Invecchiamento attivo e mutamenti del sistema pensionistico: quale impatto sui soggetti e sulle reti familiari? Autonomie locali e servizi sociali (ISSN 0392-2278), Vol. 2 (agosto), pp. 191-206.

- Facchini, Carla and Rampazi, Marina (2006). Generazioni anziane tra vecchie e nuove incertezze. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia (ISSN 0486-0349), a. XLVIII, Vol. 1(gennaio-marzo), pp. 61-88.

- Farinella, Domenica and Podda, Antonello (2020). Nota introduttiva. Sociologia urbana e rurale, XLII, Vol. 123, pp. 7-13.

- Feng, Wenmeng (2012). Social exclusion of the elderly in China: one potential challenge resulting from the rapid population ageing, In Martinez-Fernandez, Cristina, Kubo, Naoko, Noya, Antonella and Weyman, Tamara (2012). Demographic Change and Local Development: Shrinkage, Regeneration and Social Dynamics , Paris, OECD, pp. 221-230.

- Geels, Frank W. (2004). From sectoral systems of innovation to social-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Research Policy, Vol. 33, n°6–7, pp. 897-920.

- Giry, Benoit (2020). Résilience territoriale, In Pasquier, R. et al., Dictionnaire des politiques territoriales, Paris, SciencesPo, pp. 482-487.

- Glaser, Barney G. (2002). Conceptualization: On theory and theorizing using grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods , Vol. 1, n°2, pp. 23-38.

- Golini, Antonio (2005). L’invecchiamento della popolazione: un fenomeno che pone interrogativi complessi. Tendenze nuove (ISSN 2239-2378), Vol. 3 (maggio-giugno), pp. 351-360.

- Guberman, Nancy and Jean-Pierre, Lavoie (2004). Equipe vies: framework on social exclusion. Centre de recherche et d’expertise de gerontologie sociale. Montréal, CAU/CSSS Cavendish.

- Klein, Armelle (2019). Technologies de la santé et de l’autonomie et vécus du vieillissement. Gérontologie et société, Vol. 41, n°160, pp. 33-45.

- Kneale, Dylan (2012). Is social exclusion still important for older people? The International Longevity Centre–UK Report.

- Koff, Theodore H. (2019). Aging in place: Rural issues. In Aging in place, Routledge, pp. 97-104.

- Lévesque, Benoît (2013). Social innovation in governance and public management systems: toward a new paradigm? , in Frank Moulaert, Diana MacCallum, Abid Mehmood and Abdelillah Hamdouch (2013) (a cura di), The international handbook on social innovation. Collective action, social learning and transdisciplinary research , Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, pp. 25-39.

- Levitas, Ruth, Pantazis, Christina, Fahmy, Eldin, Gordon, David, Lloyd, Eva and Patsios, Demi (2007). The multi-dimensional analysis of social exclusion . Cabinet Office: London.

- Lucatelli, Sabina, Monaco, Francesco and Tantillo, Filippo (2019). La Strategia delle aree interne al servizio di un nuovo modello di sviluppo loca-le per l’Italia. Rivista economica del Mezzogiorno , a. XXXIII, 3-4(settembre-dicembre), pp. 739-771.

- Macchioni, Elena and Prandini, Riccardo (2022). Elderly care during the pandemic and its future transformation. Italian Sociological Review, Vol. 12, pp. 347-367.

- Mallon, Isabelle (2014). Pour une analyse du vieillissement dans des contextes locaux, In Hummel, C., Mallon, I. and Caradec, V., Vieillesses et vieillissements. Regards sociologiques, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp. 175-188, https://books.openedition.org/pur/68459?lang=fr

- Messina, Patrizia (2019). Innovazione sociale e nuovo welfare territoriale. Introduzione al tema monografico. Economia e Società Regionale, XXXVII, Vol. 2, pp. 9-14.

- Moffatt, Suzanne and Glasgow, Nina (2009). How useful is the concept of social exclusion when applied to rural older people in the United Kingdom and the United States? Regional Studies, Vol. 43, n°10, pp. 1291-1303.

- Morin, Edgar (2020). Cambiamo strada. 15 lezioni del Coronavirus , Milano, Raffaello Cortina, 124 pages.

- Murray, Robin, Caulier-Grice, Julie and Mulgan, Geoff (2010). The open book of social innovation , The Young Foundation.

- Osti, Giorgio (2016) (a cura di). Ricche di natura, povere di servizi. Il welfare sbilanciato delle aree rurali fragili europee. Numero monografico. Culture della sostenibilità, IX, Vol. 17.

- Pihet, Christian and Viriot-Durandal, Jean-Philippe (2009). Migrations et communautarisation territoriale des personnes âgées aux États-Unis. Retraite et société, Vol. 59, n°3, pp. 139-161. https://doi.org/10.3917/rs.059.0139.

- Pin, Stéphanie (2005). Les solidarités familiales face au défi du vieillissement. Les Tribunes de la santé, Vol. 2, n°7, pp. 43-47.

- Rossi, Giovanna and Meda, Stefania Giada (2010). La cura degli anziani, la cura agli anziani. Sociologia del lavoro, Vol. 119, pp. 114-133.

- Saraceno, Chiara (1994). The ambivalent familism of the Italian welfare state. Social Politics , Vol. 3, n°1, pp. 60-82.

- Sarti, Simone (2008). Mara Tognetti Bordogna (a cura di), I grandi anziani tra definizione e salute. Milano: FrancoAngeli, 2007, 286 pp. Sociologia (ISSN 1971-8853), Vol. 1 (Maggio-giugno), pp. 1-3. DOI:10.2383/26590.

- Scharf, Thomas, Phillipson, Chris and Smith, Allison E. (2005). Social exclusion of older people in deprived urban communities of England. European Journal of Aging , Vol. 2, n°2, pp. 76-87.

- Scharf, Thomas and Keating, Norah (2012). From exclusion to inclusion in old age. A global challenge , Bristol, The Policy Press.

- Seyfang, Gill and Smith, Adrian (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: towards a new research and policy agenda. Environmental Politics , Vol. 16, pp. 584-603.

- Turina, Isacco (2021). Consentire all’emergenza. Sulla ridefinizione dell’ordine sociale all’inizio della pandemia di Covid-19 in Italia. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia (ISSN 0486-0349), a. LXII, Vol. 3 (luglio-settembre), pp. 609-635.

- Viganò, Federica and Padua, Antonella (2018). Trasformazioni urbane e spazi sociali: la dimensione relazionale come piattaforma di sviluppo locale. Sociologia urbana e rurale , XL, Vol. 16, pp. 45-58.

- Walsh, Kieran, O’Shea, Eamon and Scharf, Thomas (2012). Social exclusion and ageing in diverse rural communities: Findings from a cross-border study in Ireland and Northern Ireland . Irish Centre for Social Gerontology.

- Walsh, Kieran, Scharf, Thomas and Keating, Norah (2018). Social exclusion of older persons: a scoping review and conceptual framework. Eur J Aging , Vol. 16, n°1, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5550622/ .

- Wang, Simeng, Schwartz, Boris and Lui, Tamara (2022). Liens sociaux au temps de la Covid-19: les personnes âgées chinoises à Paris. Gérontologie et société, Vol. 44, n° 168. DOI: 10.3917/gs1.pr1.0003.

- Zaidi, Asghar (2011). Exclusion from material resources among older people in EU countries: New evidence on poverty and capability deprivation. European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research, Policy Brief, Vol. 2, pp. 1-18.

List of figures

Figure

Figure