Abstracts

Abstract

This article compares Donald Trump’s and Jair Bolsonaro’s strategies of governance in terms of what we define here as “gore mediation.” Gore mediation is the use of different electronic media in order not only to communicate political positions but also to terrorize people into accepting exclusionary policies and discriminatory practices. The creation of artificial threats and the dismissal of real ones (like the COVID pandemic) characterizes the actions of both Trump and Bolsonaro, whose governments operate fundamentally on symbolic bases, but whose incessant print, televisual, and networked mediations have violent socio-economic consequences.

Résumé

Cet article compare les stratégies de gouvernance de Donald Trump et de Jair Bolsonaro en termes de ce que nous définissons ici comme une « médiation gore ». La médiation gore est l’utilisation de différents médias électroniques afin non seulement de communiquer des positions politiques, mais aussi de terroriser les gens pour qu’ils acceptent des politiques d’exclusion et des pratiques discriminatoires. La création de menaces artificielles et le rejet de menaces réelles (comme celle de la pandémie à la COVID-19) caractérisent les actions de Trump et de Bolsonaro à la fois, dont les gouvernements fonctionnent fondamentalement sur des bases symboliques, mais dont les médiations incessantes dans la presse écrite, télévisuelle ainsi que sur les réseaux sociaux ont des conséquences socio-économiques violentes.

Article body

Introduction: Resistance and Conformity

As is true of much of Latin America, Brazilian history is marked by multiple instances of popular resistance and confrontation with established powers. From the seventeenth century “Quilombos”—communities of fugitive slaves that strove to preserve their freedom and change the structures of servile work—to the guerilla tactics employed by the leftist combatants of the military dictatorship of the 1960s and 1970s, Brazilian culture has almost always displayed an extraordinary spirit of contestation in the face of authoritarian institutions and governments. Paradoxically, however, these episodes of resistance have also been frequently countered by a conciliatory impulse present in Brazilian culture. Brazilians usually like to avoid confrontation, and one of the founding myths of their national identity is the notion of an idyllic racial harmony between whites, blacks and indigenous people. The unreality of this harmony is repeatedly demonstrated by the uneven treatment applied to the marginalized populations of the Brazilian slums (“favelas”) by the state’s police apparatus. A perfect example of this leaning towards conciliation is perhaps the 1979 Brazilian law of amnesty, which granted full pardon for all crimes committed during the military dictatorship (on both sides of the conflict).[2] For Daniel Aarão Reis, this law ended up creating a social pact of silence that resulted in a forgetfulness of the horrors of the dictatorship.[3] Such a conciliatory spirit upholds the status quo, keeping social, economic, and political inequalities in place.

With the rise of electronic media and social networks, the rhetoric of social conciliation served to fuel a series of attacks on the Worker’s Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) in the 2018 presidential election. PT was repeatedly accused of promoting, during its 14 years in power (with presidents Luis Inácio “Lula” da Silva and Dilma Roussef), clashes between rich and poor, whites and blacks, or majorities and minorities, thus fracturing the supposedly harmonious structure of Brazilian society. Because it was immersed in a corruption scandal, the Worker’s Party could not effectively resist the massive use of social media by its main opponent, Jair Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro sold himself to the Brazilian public as the alternative to a corrupt and inefficient Left, which he characterized as mostly interested in promoting a “communist” agenda and destroying traditional institutions like the church and the family. By the third year of his presidency, however, Bolsonaro himself was facing multiple accusations of bribery and of intentionally sabotaging Brazil’s vaccination program.

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of Brazil’s political situation is how both the status quo as well as the forces resisting it have been playing out their struggle in the arena of electronic media by means of several intermedial strategies. For instance, during demonstrations against Bolsonaro in May 2021, the phrase “vai responder não, puta?” (“won’t you answer, bitch?”) became a popular motto on social media and on many placards held by the protesters. The sentence was coined by a Youtuber (Essemenino) in a humorous reference to the more than 50 unanswered emails sent by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer offering their COVID vaccine to the Brazilian government.[4] After its transposition from a YouTube video into several internet memes, the motto became an important protest slogan for popular dissatisfaction with Bolsonaro’s measures for dealing with the pandemic.

Figure 1

“Aqui quem fala é ela, a Pfizer,” meme created in June 2021, available at https://www.nsctotal.com.br/noticias/meme-pfizer-humorista-repercussao (accessed 2 December 2021).

Figure 2

“Presidente genocida,” meme, date of creation unknown, available at https://falauniversidades.com.br/memes-contra-bolsonaro-ganham-repercurssao-nas-redes-sociais-confira/, (accessed 2 December 2021).

Although it may sound sexist to some, the use of the word “puta” in the phrase evokes a series of different affective connotations typical of the subtleties of Brazilian culture—both positive and negative. If “puta” is definitely a bad word for the Brazilian conservative middle class, it is also frequently a term of endearment used among cis and trans women. This word may also indirectly and ironically refer to Bolsonaro’s presentation as an “outsider,” someone who came from the fringes of the Brazilian traditional political system, which many Brazilians consider intrinsically corrupt.

This claim to outsider status is one of the many similarities between Bolsonaro and Trump, whose campaigns were designed around the idea that only individuals who are willing to “resist” the status quo, or the entrapments and commitments of traditional politics, could solve their countries’ problems. In that sense, Steve Bannon, Trump’s main campaign strategist, may be regarded as a strange link between Bolsonaro and the former US president. As Benjamin Teitelbaum shows in his book on politics and traditionalism, Bannon considers Trump an example of the “inversion of the previous status quo” that, much like Bolsonaro himself, indirectly collaborated for his rise.[5] Bannon also shares some fundamental beliefs with Bolsonaro’s political and spiritual guru, Olavo de Carvalho, such as the need to completely reform mainstream education in the West and create schools with the purpose of waging “metapolitics.”[6]

Although characterized by its own national and cultural particularities, the Brazilian scenario is by no means unique. The uneasy combination of a history of resistance with an ideology of racial and political equality runs through much of the history of the United States, whose founding document is its revolutionary Declaration of Independence from British rule. But despite Thomas Jefferson’s opinion that the US should not go more than 20 years without some kind of political “rebellion,” the nation is dominated by a relatively stable political class divided among two parties, each of which is conciliatory in the face of capital. We take up this comparison between Brazil and the US to begin framing our discussion of the curious relationship that was formed between Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump during the first two years of Bolsonaro’s term. Bolsonaro’s affection for the corrupt, white supremacist ex-US president derived less from Trump’s policy stances than from his affective profile on social media. Mimicking many of the Trump campaign’s distinctive strategies for using digital communication and social media as political tools helped Bolsonaro both to manage a successful election campaign and to mis-manage the Brazilian nation in his first term as president.

In this essay we argue that the parallels between Trump and Bolsonaro can fruitfully be understood through the concept of “gore mediation,” which brings together two other theoretical concepts: “gore capitalism” and “premediation.” Sayak Valencia’s notion of gore capitalism is predicated on the proposition that First World discourses should pay attention to the forms of resistance developed in the interstices of the “peripheral worlds” located at the margins and borders of the globe.[7] If, as Valencia maintains, gore capitalism expresses the extreme violence of an economic system that is now based on the accumulation of bodies and deaths as a profitable business, then resistance must be carried out through the creation of subjects “who ground their existence in the reinvention of agency through a critique, a refusal to adapt, and general disobedience.”[8] Premediation, in its turn, implies the systematic use of a peculiar medial logic of anticipation, which attempts to pre-mediate a range of potential futures through print, televisual, and socially networked media formats like news, games, speculative fiction, and visual simulations.[9] Premediation works affectively by perpetuating low levels of fear and anxiety as a way to prepare the human and nonhuman elements of the mediatic system to withstand shocks produced by gore capitalism. It does this both through acts of violence against nation-states and through symbolic (and also very real) acts of violence committed by national governments against their citizens. Bolsonaro and Trump deploy strategies of mediation to the same end as gore capitalism: to terrify their opponents by multiplying premediations of authoritarian violence. We call this strategy of virtually and actually accumulating bodies and deaths “gore mediation.” We argue that Trump and Bolsonaro each took office and exercised their authoritarian powers by weaponizing socially networked media to portray themselves as political outsiders, resisting the ruling powers of their nation, and as authoritarian sources of gore mediation. One of our aims in this essay is to urge the ongoing development of resistance mechanisms within the scope of these media logics, formats, and practices.

The paper has five sections. In the first we compare Bolsonaro’s and Trump’s personal governance styles to explore the curious “bromance” between these two authoritarian leaders (a notion fueled by Brazilian media). Next, we explore the hidden roots of Bolsonaro’s and Trump’s agendas, exposing their gendered politics as a way of exerting power over the bodies of the marginalized and disenfranchised. The third section unpacks Valencia’s concept of gore capitalism, developed in the first instance to account for the violence of drug cartels around the Mexican-US border, in relation to Bolsonaro’s violent actions in Brazil. Drawing together the violent premediations of both Bolsonaro and Trump, the next section connects gore mediation to their similar use of different media channels to promote a necropolitics[10] that perpetuates racialized violence against immigrants and minorities. The final section deploys our concept of gore mediation to make sense of the Trump-fueled insurrection attempt to stop the pro forma Congressional certification of Joe Biden’s election. Spurred on by Trump’s multiple acts of gore mediation in the weeks leading up to the January 6 insurrection, nearly a thousand of his supporters breached the US Capitol building in order to resist the quadrennial peaceful transfer of power that US political ideology proclaims as one of the distinctive features of its electoral system. Similarly, Bolsonaro has repeatedly expressed veiled threats of a military coup in the eventuality of his impeachment, a possibility that became more palpable after the institution of a congressional hearing (CPI) to assess his responsibility for the more than 500 000 pandemic-related deaths. We highlight these similarities between the US and Brazilian political situations in the belief that more efficient means of resistance require greater awareness of how the rise of global conservative and reactionary forces was fueled via the “total mediation” of digitally networked social media platforms.[11]

Trump of the Tropics

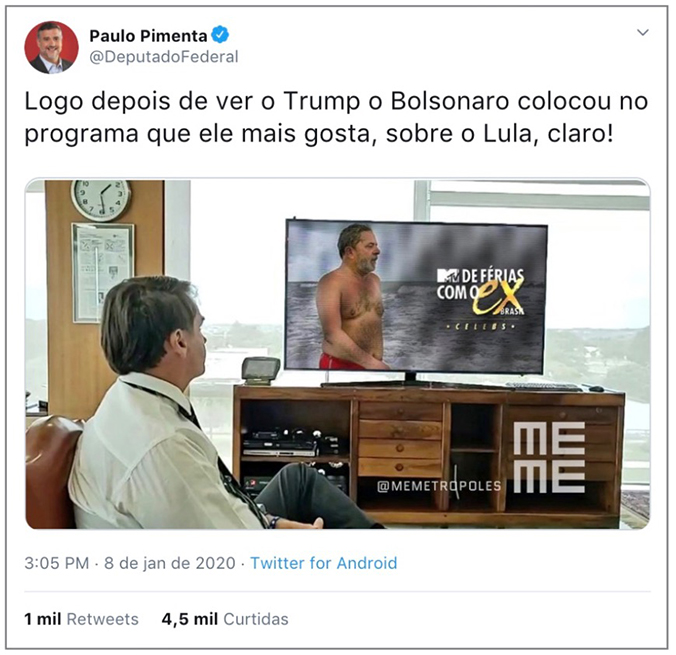

On January 8, 2020, Brazilian media eagerly covered what seemed to be a very trivial fact: Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro recorded a live video for his social media networks while watching Donald Trump’s address on the then-recent attacks on American military bases in Iraq by Iranian forces. The video consisted of images of Bolsonaro attentively following the Portuguese translation of Trump’s speech and then remarking on the mistakes made by his leftist predecessor, former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, regarding foreign politics.

Figure 3

Bolsonaro watches Trump’s speech, 8 January 2020, available at Gazetadopovo.com.br, https://www.gazetadopovo.com.br/republica/breves/bolsonaro-assiste-ao-discurso-de-trump-e-transmite-nas-redes-sociais/ (accessed 2 December 2021).

Stemming from the ironic effects of hypermediation (Trump is displayed on Bolsonaro’s television set and the whole scene is reproduced in digital networks only to be later remediated by traditional analog media like print and television), these images offered rich material for the production of memes that were widely shared on the Internet. Some of these memes explored Bolsonaro’s over-the-top admiration for Trump, which many people in Brazil regard as contradicting his nationalistic discourse, while others explored the conflicted relationship between Bolsonaro and Lula. In one of these memes, for instance, the image on Bolsonaro’s television set is of Lula on the beach wearing a bathing suit accompanied by the logo of the Brazilian version of a popular MTV reality show, Ex on the Beach (April 19, 2018–February 27, 2020). In another, Bolsonaro just looks at Trump and says, “I love you.” This second meme perfectly encapsulates the idea of Bolsonaro as the “Trump of the Tropics,” a trope that has been repeatedly reinforced by Brazilian and international media.[12]

Figure 4

Figure 5

In fact, from the beginning of his term, Bolsonaro has made a point of highlighting his allegedly close relationship with the American president and his government’s policy alignment with U.S. ideals and values. Bolsonaro’s unabashed veneration for the U.S. has frequently reached laughable heights, as when he saluted the American flag during an event promoted by the Brazilian-American Chamber of Commerce in Dallas in May 2019. During Trump’s term, Bolsonaro maintained that his friendship with Trump was extremely beneficial for Brazilian businesses and the economy. However, any practical benefits of this so-called partnership between the countries was hard to determine. While the Brazilian government kept trying to please Trump with benefits, such as granting the use of Alcantara’s military base in Maranhão for the launching of American satellites, or waiving all visa requirements for American tourists, Trump responded by withdrawing his previously promised support for the Brazilian claim to membership in the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). Even after Trump removed Brazil in February 2020 from the list of emergent nations that enjoy special treatment in terms of international commerce, Bolsonaro defended his American counterpart from the U.S. media’s frequent criticism, stating “The guy has diminished unemployment, improved the economy, helped the Latinos that live there…perhaps it’s because the press is not interested in good news. I wonder if that’s the reason.”[13] Carta Capital, an important Brazilian news outlet, went as far as to define Bolsonaro’s bromance with Trump as a ridiculous story of unrequited love, something that “would be comical if it were not also tragic”[14] for the South-American nation.

Much of Bolsonaro’s persona was built on an authoritarian imaginary that, while part and parcel of Brazilian culture, is also a feature of right-wing Republican voters in the US, who are markedly more authoritarian than their Democratic counterparts. The Brazilian authoritarian imaginary is the result of centuries of exploitative and exclusionary policies in the country’s history. Recent research demonstrates that, on a scale from 1 to 10, Brazilians tend to score 8,1 in terms of authoritarian inclinations.[15] It is particularly meaningful that the highest numbers are found among people of color. Several explanations for this phenomenon could be hypothesized here, but the most relevant step is to acknowledge the strong leanings towards authoritarianism inherent in Brazilian culture. This is an interesting expression of the many contradictions involved in the dialectics of resistance and conformity present in Brazilian culture. Many of Bolsonaro’s supporters see his authoritarian tendencies as courageous acts of resistance to the pressures of the corrupt establishment, often symbolized by institutions like the Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal, STF). Bolsonaro lives up to the moniker “o mito” (“the myth”), due not only to his “courage” to express the most outrageous notions, without any filter whatsoever, but also to his defense of violence as an all-encompassing resolution for Brazilian problems. This applies to the problem of crime in large cities as well as the obstacles created by Brazilian institutions and bureaucracy. Many of his followers go as far as to defend the idea of a “legal coup,” by means of which Bolsonaro would be able to govern without the legislative hindrances created by institutions like the Superior Court.

This reasoning, which is similar to that according to which Trump was elected and continues to govern, couldn’t be more straight-forward: if only Bolsonaro was left alone, freed from all the troublesome mechanisms meant to ensure the balance of power in a democratic society, then endemic problems like corruption would finally disappear. Although constantly involved in corruption scandals, Bolsonaro and his family (his sons Eduardo, Flávio and Carlos are, respectively, a congressman, a senator and a city council member) were elected on the basis of an anti-corruption platform. Bolsonaro’s candidacy came in the wake of a huge corruption scandal involving the Worker’s Party and resulting in the imprisonment of former president Lula. This total contradiction between anti-corruption rhetoric and consistently corrupt actions also informed the Trump administration and Trump’s family as well, particularly his sons Eric and Don, Jr., his daughter Ivanka, and her husband Jared Kushner.

The almost slavish admiration of Bolsonaro for Trump, however, seems to go beyond a mutual authoritarianism and the mere allure of the North-American model of capitalism and governance; it is grounded as well in specific interpersonal connections between the two circles. According to Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo, Steve Bannon, Trump’s main campaign strategist, provided the Brazilian president’s team with valuable “tips” and guidance before the 2018 elections. Some people in Brazil even suspect that Bannon’s support was more formal and consistent than just a few pointers. According to Ciro Gomes, a Brazilian politician who was also a candidate during the 2018 presidential elections, Bannon was likely responsible for the “slush funds” that financed the massive distribution of Whatsapp messages with fake information about Bolsonaro’s main adversary from the Worker’s Party (PT), Fernando Haddad. Bolsonaro’s campaign is now being targeted by an investigation involving a group of businesspeople that allegedly spent well over 12 million reais (more than two million dollars according to current exchange rates) for anti-PT propaganda on Whatsapp, a strategy directly out of the Bannon playbook.[16] The media mogul can thus be seen as a “medialogical” connection between Trump and Bolsonaro, an important piece of the necropolitical mechanism that lies at the center of both governments.

Bolsonaro’s use of Whatsapp is based mostly on the multiplicative power of the platform, which facilitates the distribution of content among closed groups and outside of them. Research demonstrates the malleability and intermedial character of the platform among groups of Bolsonaro’s supporters, since at least 65% of its shared content comes from sites such as YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram.[17] This pattern is typical of what can be called a hybrid media system,[18] which departs from a linear perspective of media evolution “in favor of an intricate technological and social media that intersects and cross schedules between the mass media and digital platforms.”[19] In Brazil, Whatsapp reaches at least 120 million people. Many users consider it a safer source of information than most other apps for social networking, like Facebook and Twitter; paradoxically, there’s also research showing that more than 14% of users intentionally share false information on the platform.[20] According to Piaia and Alves, Bolsonaro’s media strategy is quite similar to that of the Brexit and Trump campaigns, especially in regards to the use of subterranean strategies of non-official communication.[21]

What kind of concrete links can be traced between Bolsonaro’s campaign and Bannon’s methods? In War for Eternity (2020) Benjamin Teitelbaum offers potential support for speculations about the Bannon connection via the mediation of Olavo de Carvalho, Bolsonaro’s political “guru.” In the chapter “Dinner at the Embassy,” Teitelbaum describes a fascinating meeting that took place in January 2018 between Brazilian businessmen, Bannon, and Carvalho at Bannon’s townhouse in Washington. This social event was motivated mainly by Bannon’s interest in Carvalho, a very controversial éminence grise in Bolsonaro’s circles, who is also an ex-astrologer turned popular YouTube “philosopher” and political commentator. Two months after that meeting, Bolsonaro himself would be present at another dinner with Steve Bannon, this time at the residence of the Brazilian ambassador in Washington. According to Teitelbaum, the ambassador’s

decision to invite Steve to the dinner was also provocative. Steve no longer held any official position in the White House or in the government […]. The guest list at the embassy thus testified to Steve’s continued high status in the eyes of the Brazilian government but also Bolsonaro’s confidence in his relationship with Trump. He adored the U.S. president, hardly ever missed an opportunity to praise him in social media, and would greet him the next day at the White House with a Brazilian soccer jersey emblazoned with the Trump name.[22]

In the face of these connections, it makes sense for Teitelbaum to dedicate several pages of his book to Bannon and Carvalho. If his hypothesis is correct, they are both important actors of a global circle of power brokers intent on fighting globalism and creating a new, reactionary, and spiritual world order in which the United States is meant to assume the position of the strategic leader of Western civilization. Carvalho’s relationship with Bannon also proves to be an important element of the Bolsonaro-Trump bromance.

Seen as the most important contemporary intellectual mentor of Brazilian neoconservatives, Carvalho became a key agent for the transformation of the country’s political scene. With more than 705 000 followers on Twitter as of July 30, 2021, he has been actively engaged in a “culture war” whose main goal is to undo the alleged dominion of the left over the media, government, and academic institutions—a move similar to, if not modeled after, the culture wars of Bannon, Trump, and the Republican party. After a long career as a professional astrologer, Carvalho became famous for his controversial anti-leftist articles in different newspapers and magazines. His online “philosophy courses” have been attended by more than 12 000 people, most of whom have become “disciples” of the master. Carvalho is a fundamental contributor to the development of Brazil’s neoconservative imaginary. Grounded in the idea of a global conspiracy for the establishment of a transnational leftist regime, this imaginary presents Bolsonaro and Carvalho as messianic figures capable of saving the country from the perils of international communism. It is precisely the messianic character of his mission that legitimates Bolsonaro’s authoritarian aspirations among his supporters. According to this perspective, he is the only person capable of assuring the preservation of traditional Christian values in a war against indigenous groups, leftist intellectuals, LGBT+ people and whomever else may threaten the stability of the conservative worldview. These culture wars mark another important parallel between the current Brazilian and the former U.S. administrations, as does the feeling among their evangelical followers that Trump, as well as Bolsonaro, had been chosen by God. These and other similarities contributed to the repeated characterization of Bolsonaro as the Trump of the Tropics.

Traditionalism and Gender Ideology

Like Steve Bannon, who has expressed his admiration for the Brazilian “philosopher” on more than one occasion, Carvalho and the Russian Alexander Dugin are important players in the far-right circle of “global power brokers.”[23] As believers in a “traditionalist” worldview, they all profess a faith in the historical task of conservatism to reform the world. Because history operates in a cyclical manner, traditionalism claims, humanity is now arising from a long cycle of decadence. Modern ideas are inherently dangerous for the spiritual health of societies, and the radicality of traditionalist positions (after all, they have the messianic task of announcing or premediating the triumph of conservativism) makes it “hard to imagine Traditionalism ever operating within the institutions of contemporary democratic politics.”[24] In fact, traditionalists believe they are in the vanguard of the resistance against a wave of societal changes connected to the process of globalization. The paradox of a conservative movement that presents itself as a revolutionary force was at the heart of German and Italian fascism before the Second World War and has affinities with the peculiar attraction exerted by 21st century conservatism over large contingents of the Internet generation. Angela Nagle describes our peculiar contemporary situation (albeit ahistorically) as one “in which to be on the right was made something exciting, fun and courageous for the first time since… well, possibly ever.”[25]

Traditionalists across the globe are especially motivated by threats posed by changing ideas pertaining to gender and sexual identity. In Brazil, the most notorious incidents preceding Bolsonaro’s election involved the distribution of fake news concerning the topic of “gender ideology”—a strategy modeled on Trump’s 2016 campaign against Hillary Clinton. The first piece of fake news was presented by Bolsonaro himself, who denounced the distribution of what he termed a “gay kit” (containing books and leaflets) to Brazilian public schools. Although this material was never actually used by the previous government, Bolsonaro’s appearance on national television with a copy of the books was enough to instill panic among conservatives. The other incident, which gained an almost mythical character in Brazilian cultural life, consisted in the allegation that the Worker’s Party candidate, Fernando Haddad, while acting as mayor of São Paulo, had provided the city’s public daycares and schools with baby bottles in the shape of small penises. This absurd allegation was spread mainly through Whatsapp, which is largely used by Brazilians as an important source of information and quick communication. The story of the “mamadeira de piroca” (“penis shaped baby bottle”), an episode known to virtually every Brazilian, embodies the philosophy behind Bolsonaro’s strategy of governance, as well as that of his campaign.

Bolsonaro’s hetero-patriarchal gender politics have their roots in the 2014 elections, when Brazil elected the most conservative National Congress to date, with Evangelicals playing a fundamental role therein. Representative Erika Kokay, from the opposition Worker’s Party, coined the expression “BBB caucus,” meaning “bullets,” “bulls,” and “Bible,” in order to describe this conservative political faction composed of ex-military and gun rights supporters, rural landowners, and Evangelicals. Like white suburban women who support Trump, Evangelical women do not identify with feminism, and engage in a fight against what Brazilian Christians have been defining as “ideologia de gênero” (“gender ideology”), a policy that was supposedly promoted by the Worker’s Party. Within the Brazilian neoconservative imaginary, “gender ideology” is likely the worst enemy since it is supposed to corrode family values and promote an LGBT+ agenda in schools and other public institutions. Bolsonaro’s choice of an extravagant female Evangelical pastor for minister of “Women, Family and Human Rights” can be read as an attempt to suppress policies that benefitted racial and ethnic minorities and women.

Before the 2018 election, however, Bolsonaro repeatedly made outrageous comments about women, which generated a large-scale opposition movement grounded in feminism and women’s rights similar to the huge women’s march in the U.S. capitol to protest Trump’s election on Inauguration Day. Large protests were staged in cities like Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, and an opposition movement was organized on Twitter and through Facebook groups like “Mulheres Unidas contra Bolsonaro” (Women United Against Bolsonaro), which had 3,8 million members just a few months before the election (September 2018). The hashtag #EleNão (“not him”) even became a popular motto in Brazil. It was the largest women’s protest ever to happen in Brazil, with an estimated 100 000 people parading on the streets of São Paulo. But at the same time, Bolsonaro had the support of conservative evangelical Christians (including women), which make up more than 30% of the Brazilian population, according to a recent poll.[26] As with Trump in the US, the more intense and widespread the opposition to Bolsonaro the more strongly his supporters have rallied behind him.

Gore capitalism

Another way we might think about the relation between Bolsonaro and Trump is not from the perspective of Bolonaro’s admiration for, and imitation of, the U.S. president, but from the perspective of an economic and political logic distinctive to Latin America that has begun to be exported from the Third World to the First. As stated previously, Sayak Valencia has characterized this logic as “gore capitalism,” the result of an alliance between state violence, drug trafficking, and necro-power that lays bare the worst dystopias of globalization. Valencia sees gore capitalism as a Third-World, borderland phenomenon of necro-empowerment in which “the only measure of value is the ability to mete out death to others”[27] and bodies are the commodities to be accumulated rather than wealth. She develops the concept of gore capitalism by way of her analysis of the intense violence endemic to illegal drug economies within the “narco-state” of Mexico, and between Mexico and the U.S. at border sites like her home town of Tijuana. Although Valencia describes gore capitalism as a largely Third-World phenomenon, the similarities between Bolsonaro and Trump that we have been discussing support her contention that gore capitalism has begun expanding from the Third World to the First. As Valencia asserts, “this form of capitalism is now found in all of the so-called Third World countries as well as throughout Eastern Europe. It is close to breaching and taking up residence in the nerve centers of power, otherwise known as the First World. It is crucial to analyze gore capitalism because, sooner or later, it will end up affecting the First World.”[28]

It is not difficult to see a Brazilian form of gore capitalism in Bolsonaro’s defense of state (and even quasi-legal) violence against crime, always one of the most important points of his political platform. As far back as 1992, in the aftermath of a historical massacre of rebellious inmates at the Carandiru prison in São Paulo, when 111 prisoners were killed, Bolsonaro had declared: “only a few have died. The police should have killed more.” The accumulation of bodies by police is seen here as a long-standing measure of value for Bolsonaro. It is precisely this violent lack of self-restraint that garners the support of his political base, which sees Bolsonaro (like Trump supporters see him) as “authentic,” “honest,” and “truthful”—and, therefore, different from most Brazilian politicians. In fact, the more outrageous and violent his statements became over time, the greater seemed to be his appeal to the Brazilian elites and the middle class. He remains an outspoken supporter of the former Brazilian dictatorship, whose greatest mistake, according to him, was “to torture instead of killing.”[29]

Valencia characterizes her analysis of gore capitalism as transfeminist, insofar as it highlights its gendered and racial components. Because bodies are its main commodities they are subjected to predatory techniques of extreme violence that more frequently target individuals with marginal identities (women, transsexual people, blacks, etc.). Ribamar Junior describes this violence operating in Bolsonaro’s government, which “can exacerbate gore practices in Brazilian politics by means of its attempt to follow neoliberal logics, moreover in the context of the legitimation of gender violence based on the ideological argument of morality characteristic of right-wing politics.”[30] The fact that 75% of homicide victims in Brazil are black and that violent acts against LGBT+ people are increasing dramatically[31] indicates the existence of a hospitable environment for the deployment of Bolsonaro’s necro-politics, with their trafficking in violence and death.

In this light the nickname “the myth” might reveal more than originally intended by Bolsonaro’s supporters. His government is as devoid of substance as it is filled with mythical fantasies, imaginary enemies, symbolic and real violence, and fictions like the miraculous power of Hydroxychloroquine to prevent Covid. When one considers that the majority of Covid deaths in Brazil are concentrated in the poor neighborhoods of cities like Rio de Janeiro, Bolsonaro’s politics of violence and exclusion become very concrete. His pandemic politics powerfully illustrate Achille Mbembe’s thesis about the inherent (but hidden) violent nature of modern democracies, including their illegal forms. After all, most of the affected people live at “the edge of life,” fueling a necropolitics that “proceeds by a sort of inversion between life and death, as if life was merely death’s medium.”[32] Necropolitics is “indifferen[t] to objective signs of cruelty” in practices like Bolsonaro’s politics of “hygienization.”[33] Based on the material destruction of imaginary enemies (“communists” or LGBT+ people) and black, poor, and marginalized communities surviving at the edges of Brazilian society, such hygienization has its predecessors in many fascist regimes, most notably in Germany’s Third Reich.

The racialized gore capitalism fueling Bolsonaro’s election to the presidency was built in part upon the traditionalist ideas of Carvalho. Like Bannon was for Trump, Carvalho was instrumental in securing the presidency for Bolsonaro, in large part due to deploying the violent rhetoric of gore capitalism. Seen as the most important intellectual mentor of Brazilian neoconservatives, Carvalho became a key agent not only for the transformation of the country’s political ideology but also for the transformation of its mediascape. Before the election, Carvalho repeatedly “premediated” a Bolsonaro presidency on blogs and social media, going as far as to declare in one blog post that “Bolsonaro is the only right-wing politician capable of winning the 2018 election. Boycotting him under any pretext doesn’t simply mean to divide the right, but rather to kill it in its crib.”[34] Carvalho’s mobilization of various social media platforms helped make him a fundamental contributor to the development of Brazil’s neoconservative imaginary across the nation’s mediascape. Grounded in opposition to a phantasmatic global conspiracy aimed at the establishment of a transnational leftist regime, this imaginary premediates both Bolsonaro and Carvalho as messianic figures capable of saving the country from the perils of international communism through the operations of what we call “gore mediation.”

Gore Mediation

Where gore capitalism uses violence and murder to accumulate bodies and measure value, the examples of Carvalho and Bannon suggest that the measure of value for Bolsonaro and Trump is the accumulation of likes, shares, and retweets through the violence of mediation, what we understand, following Valencia, as “gore mediation.” Through this technique, both presidents use media and mediation to perpetuate affective, embodied violence against their citizens. For Bolsonaro as for Trump social media and other forms of mediation are weaponized not just as vehicles to represent their authoritarian personalities or their neofascist beliefs or policies, but as agents or actants that themselves frighten or terrify people, that inflict psychological and physiological violence through mediation itself. Like Trump (and arguably with more flippancy), Bolsonaro delights in producing controversial statements, which are widely shared on social media by his fans. Trump and Bolsonaro each resort to social media in order to terrorize opponents as well as supporters. Bolsonaro scares people with the ever-present danger of the “communist coup,” as Trump does with antifa and the “radical left.” Following Trump, Bolsonaro took the presidency by taking control of the Brazilian mediascape via WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook. This gore mediation created what Heidegger might call a mood or “Stimmung”[35] or Raymond Williams a “structure of feeling,”[36] in which his supporters could identify with and imitate his right-wing threats of violence.

How are we to understand the relation between these violent mediations and the acts of violence they inspired during the four years of Trump’s presidency and the first three years of the Bolsonaro administration? One way might be through the idea of “stochastic terrorism,”[37] a term coined by an anonymous blogger in the wake of the failed assassination attempt against Democratic U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords in Tucson, Arizona in January 2011. Stochastic terrorism, “the use of mass communications to incite random actors to carry out violent or terrorist acts that are statistically predictable but individually unpredictable,”[38] helps to explain, in a general sense, relations among mediation and violence. But the concept also makes it difficult to assign legal responsibility for any particular act of terrorist violence since such acts are random and individually unpredictable.

Indeed, stochastic terrorism currently has no legal status in the U.S. or Brazil. But the concept nonetheless helps to explain how gore mediation works to encourage random violence even when no specific chain of causation can be identified. To assign responsibility for acts of violent mediation we prefer the concept of gore mediation to stochastic terrorism, in part because the latter considers acts of violent mediation and communication to be ontologically secondary to acts of violence—even though those very acts of mediation are chronologically prior to the terrorist violence itself. With the concept of gore mediation we want to emphasize that such inflammatory mediations are violent in themselves. Both Trump and Bolsonaro use gore mediation to inflict affective, emotional, social, and psychological pain (all of which have real social, economic, and physiological effects) on their targets. Simultaneously, these same gore mediations license, inflame, and empower their supporters to act violently in the mediascape and in the public arena against Bolsonaro’s enemies, which they perceive as their own.

Like many forms of “fake news” in our purportedly “post-truth” era, gore mediation operates independently of the truth or falsity of its claims or information; it is indifferent to accuracy, facts, or consistency. Bolsonaro’s behavior on Twitter is similar to Trump’s in regard to the propagation of highly questionable information aimed at terrifying or causing pain among those whom he considers his enemies. If Trump uses Twitter to promote his white supremacist conspiracy theories, Bolsonaro engages with social media (but also traditional media) in order to create social panic and terrorize leftists and LGBT+ people.

In Brazil, Bolsonaro’s mistakes when retweeting fake news coming from non-credible sources have become almost folkloric, as is also the case for Trump’s in the US. Although there is no official research on the subject, it is possible to assume that the frequency of the lies told by Bolsonaro on Twitter compares to that of Trump—at around 4.9 misleading claims per day during his first 100 days of the presidency, according to The Washington Post.[39] In fact, on March 29, 2020, Twitter removed two of Bolsonaro’s tweets about the COVID pandemic because they contained statements suggesting that an effective medicine against the virus already existed (again, like Trump, Bolsonaro was, and still is, a promoter of Hydroxichloroquine as a miraculous drug for fighting COVID-19).

This use of social networks as a means of control, stochastic terrorism, and ideological narrativization has been a hallmark of Bolsonaro’s government since the beginning. In March 2019, Bolsonaro practically launched a campaign against Brazilian journalist Constança Rezende on Twitter, accusing her of working for his impeachment and unjustly persecuting his son, Flávio Bolsonaro. His supporters immediately started swarming to attack the journalist on social media, and conservative blogger Allan dos Santos even published fake tweets under Rezende’s name in order to incite the virtual lynch mob.

Like Trump in 2016, Bolsonaro’s rise to power in October 2018, represents the materialization of a long process of gore mediation strategies performed through different social media and digital platforms over the last two decades. It is estimated that 80% of the 1690 Whatsapp bot accounts used to promote Bolsonaro before the elections are still active today. Like Trump, Bolsonaro is well aware of the importance of fake news and scare tactics for maintaining his popularity. His use of digital media has been carefully planned to maximize a kind of “shock effect” that assures his constant presence in the news. Although his popularity has decreased over recent months, especially after his erratic and irresponsible handling of the Coronavirus pandemic in Brazil, Bolsonaro is still the strongest candidate for the 2022 elections.[40] Even the current death toll due to the COVID outbreak (more than 544 thousand recorded as of April 2021) is not enough to significantly damage Bolsonaro’s popularity among his supporters. In fact, when asked by a reporter in April 2020 about the rising contamination rates and death statistics, Bolsonaro contented himself with sarcastically replying “I’m not a gravedigger, ok?”[41]

We have analyzed some of the powerful reasons why people have insisted on calling Bolsonaro the Trump of the Tropics. But in thinking about the practices of gore mediation, we have also underscored the way in which the gore capitalism of the Third World has begun to make its way into the First World, particularly the United States, as president Trump’s violent threats on social media—whether aimed at immigrants, people of color, Democrats, his own administration, Black Lives Matter protesters, or foreign leaders—are always designed to terrorize others to do what he wants. In this way, Trump’s tweets can be seen as violent mediations in themselves. We witnessed Trump’s violent tweets repeatedly over the course of his presidency—in threats of massive violence against North Korea’s Kim Jong Un or Iran’s Hassan Rouhani, or direct threats against refugees, other nations, and transnational alliances. Trump not only used gore mediation to destabilize or unsettle political leaders worldwide but also to inflict collateral affective damage on the U.S. media public. Similar to Bolsonaro, Trump’s incessant attacks on the U.S. news media, his own justice department, Democrats, the courts, the environment, women, trans individuals, and people of color transformed the Trump presidency and its incessant gore mediation into a pervasive and almost constant threat to the American public.

In the context of gore capitalism, which Valencia traces in large part to the drug trade across the US-Mexican border,[42] it is worth remembering that Trump opened his campaign for the presidency in 2015 by demonizing Mexican immigrants as rapists and drug dealers. In fact, throughout his administration he focused obsessively on a series of measures aimed at protecting U.S. borders: executive orders restricting immigration from Muslim majority nations; unending calls to build a wall on the Mexican border; the narco-empowerment of ICE to imprison, abuse, and (directly or indirectly) kill refugees apprehended and detained in border camps. In these and many more instances Trump has mobilized a wide variety of mediation platforms to articulate his violent white nationalist vision. In light of his adoption of the logic of gore mediation to perpetuate violence against Americans of color and others who would oppose his rule, it might make as much sense to call Trump a First World Bolsonaro as it does to call Bolsonaro the Trump of the Tropics. In this context, it is also worthwhile to consider the long-lasting ties of Brazilian politics to drug trafficking, as well as the alleged connections between Bolsonaro and the militia engaged in permanent battle with local drug dealers for the domination of Brazilian slums (especially in Rio de Janeiro, one of the country’s largest cities).[43] In either case, what seems clear is that both men have remediated the logic of gore capitalism into a form of gore mediation that uses all available media formats and platforms to perpetuate quasi-legal violence against the very nations they had been lawfully elected to govern.

Insurrection and Resistance

If Trump kicked off his campaign for president on June 16, 2015, with an act of gore mediation directed against people of Mexican descent, he culminated his presidency on January 6, 2021, with a virtuoso performance of gore mediation directed against Congress, the U.S. Constitution, and the American people, who had voted for a peaceful transition of power through their free and fair election of Joe Biden as president. Beginning well before the November 3, 2020 election, Trump and his followers had begun to premediate widely the idea of a stolen election in which Trump would be falsely defeated.[44] Informed by his own internal polling, Trump began to predict as early as September that he would be leading in the vote count in many states when early results were in but that overnight there would be massive dumps of illegal votes for his opponent. Trump began premediating the stolen election narrative in print, televisual, and networked news media, knowing full well that early reporting districts (including especially rural and small-town communities) would lean heavily in his favor and show him in the lead, but that major metropolitan areas, which held many more voters and which overwhelmingly supported Biden, would inevitably take longer to count and report their results. By premediating a stolen election well before it happened, Trump was able to convince millions of his followers that the election had been stolen and that he was the rightful winner. In so doing, he reinforced their own understanding of themselves as agents of resistance, acting against the hegemony of mainstream liberal media.

Trump’s premediation of a stolen election was countered by that very mainstream media with warnings about his plans to refuse to accept an electoral defeat, plans which were unfolding in plain sight. Arguably the most prominent of these warnings was Barton Gellman’s viral Atlantic essay, first published online in September 2020, which premediated a variety of troubling scenarios in the event that Trump would refuse to concede.[45] Although the aim of Gellman and others in alerting the American public to this possibility was to prevent it from happening, these premediations had the opposite effect. Despite coming from the opposite end of the political spectrum as Trump’s premediation of a stolen election, premediations of Trump’s refusal to accept an electoral defeat contributed instead to the likelihood that for the first time in its history, the U.S. might not have a peaceful transition of power from one president to the next. As it had in the run-up to Trump’s election in 2016, the print, televisual, and networked media helped bring about and normalize the very actions they sought to preempt.[46]

As we now know, Trump did in fact refuse to accept defeat and continued throughout what is traditionally known as the lame-duck period of the presidency to insist that Biden’s election was rigged. Desperate to hold on to power, Trump and his allies launched a multi-state campaign to invalidate the election results of states that he had won in 2016—primarily Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—both through unsuccessful lawsuits in the courts and through persuading Republican officials to invalidate their state’s results. When these efforts failed to change a single vote, the stage was set for Trump’s last stand: the battle to prevent Congress from completing its essentially ceremonial certification of the electoral college results sent to them from the states. Scheduled for January 6, 2021, the certification will be remembered as marking the day that right-wing, white supremacist Trump supporters violently assaulted the United States Capitol, terrifying elected officials and their staffs, and ultimately killing several people. This attempted insurrection, understood by its participants as an act of resistance, had been premediated for weeks both on right-wing social media networks and in the mainstream media, including repeatedly by Trump himself. This gore mediation culminated in the January 6 speech to thousands of his supporters outside the White House, in which he urged them to march down Pennsylvania Avenue to the U.S. Capitol in order to stop the steal, i.e., to prevent through violent means the Congressional certification of the election results.

In the immediate aftermath of the attempted insurrection, the New York Times published an account of how Trump and his right-wing supporters premediated a violent attempt to stop the election on January 6. The earliest of Trump’s multiple tweets encouraging violence on January 6 that was noted by the Times occurred on December 19: “‘Big protest in D.C. on January 6th,’ Mr. Trump tweeted on Dec. 19, just one of several of his tweets promoting the day. ‘Be there, will be wild!’”[47] The Times article noted several other Trump tweets premediating action on January 6:

Dec. 27: “See you in Washington, DC, on January 6th. Don’t miss it. Information to follow.”

Dec. 30: “JANUARY SIXTH, SEE YOU IN DC!”

Jan. 1: “The BIG Protest Rally in Washington, D.C. will take place at 11:00 A.M. on January 6th. Locational details to follow. StopTheSteal!”

That same day, a supporter misspelled the word “cavalry” in tweeting that “The calvary is coming, Mr. President!”

Mr. Trump responded: “A great honor!”[48]

On December 19th, well ahead of other mainstream media, Fox News had already amplified Trump’s initial tweet with a story that “Trump promises ‘wild’ protest in Washington DC on Jan. 6, claims it’s ‘impossible’ he lost.”[49] Ten days later, The Washington Post published its own less volatile premediation, “Jan. 6 protests multiply as Trump continues to call supporters to Washington.”[50] And of course there were countless tweets and retweets, Facebook posts, and entries on right-wing social media outlets like Parler and Gab, calling for and planning violent action on January 6. As with gore mediation generally, the violence of Trump’s initial premediations of insurrection could be measured by the large number of retweets, shares, likes, and posts multiplying across the print, televisual, and socially networked mediascape, not only by those who supported and would join in the January 6 violence but also by those in the mainstream media who would oppose such violence. Where gore capitalism takes injured and dead bodies as its metric, gore mediation is measured by the generation of fear and anger through the proliferation of mediations.

Gore mediation operates largely to generate and intensify affects like fear and anger among the populace, creating a mood or structure of feeling in which violent actions could and usually would emerge. But January 6 was different in that it focused specifically on particular actions on a particular date. Less stochastic terrorism than incitement to violence, Trump’s gore mediations leading up to and especially on January 6 itself led directly to the attack on the Capitol by his followers, many of whom had been preparing for this attack for weeks. Indeed, at the January 6 protest in front of the White House, Trump twice encouraged his audience to march down the street to the Capitol (even promising to join them) in order to embolden Republican members of Congress to oppose the confirmation of Biden’s victory as well as to terrorize those members who supported confirming the vote. The stunning events of January 6, including Trump’s repeated encouragement of violence against Congress and reluctance to condemn or call off the attackers, have been well documented, including in a powerful 40 minute “Visual Investigation” video assembled by the New York Times.[51] For our purposes in this essay, what all of these media accounts share (whether before, during, and after the violence of January 6, in favor of or scandalized by the attempted insurrection) is their participation in the process of gore mediation that marked the authoritarian leadership not only of Trump and Bolsonaro, but of other right-wing leaders across our hypermediated world.

If the global mediascape serves as the battleground between democracy and fascism, or popular and autocratic government, how is the authoritarian violence of gore mediation to be resisted? Mainstream media see themselves as resisting the authoritarian white supremacy of Trump and his supporters by debunking and countering what is now widely understood as “the big lie” that the presidency was stolen from Trump by Biden and the Democrats. This journalistic resistance to Trump’s fascistic domination of the U.S. and global mediascape is emblematized most clearly in the slogan adopted by The Washington Post in the first weeks of the Trump presidency, “Democracy Dies in Darkness.” But the rhetoric of resistance no longer belongs solely to the disempowered and oppressed but to those whose privilege appears to be challenged. Trump and his followers also see themselves as resisting the lies and fake news of the media. And insofar as Trump’s election followed eight years of an Obama-Biden administration, and has now been succeeded by a Biden presidency, the Trumpists see their four years in the White House as resisting the dominance of globalism and liberalism. Curiously these conflicting accounts of media and politics share a commitment to seeing themselves as resisting the political status quo.

As the editors of this special issue note, however, “resisting can no longer be understood only as an act of opposition but is, also and above all, an act of interruption (that diverts, suspends, cuts, intersects) or decolonization of the flows of a normalized sensibility by the new devices for the production of the sensible.” Because virtually all major political parties in the U.S. and across the world are funded by and work in service to capitalism, the possibility of opposition has become more difficult than ever. It is impossible, for example, to see Biden’s defeat of Trump as any real form of opposition to the white supremacy on which the United States was founded and still upholds. Thus, decolonizing movements like #BlackLivesMatter are less likely to function in opposition to the structural racism of nations like the U.S. than as interruptions of our normalized sensibilities. And in the third decade of the 21st century, the production of the sensible occurs most powerfully in the realm of our everyday media.

The most effective way to resist the globalized violence of gore mediation is through the very devices for the production of the sensible that leaders like Trump and Bolsonaro rely upon for asserting and maintaining their authority. In the case of Trump, there turned out to be no successful political mechanism through which to prevent him from fulfilling his term in office, despite a historically unprecedented two impeachment attempts by the Democrats (the second of which occurred just one week after his incitement of the January 6 insurrection). But there was, however, an arguably more important effort to resist his power by removing him from social media. In the aftermath of the January 6 insurrection Trump’s unceasing regime of gore mediation was interrupted by the three major social media networks in the US: Twitter says it has banned Trump permanently; Facebook has extended his ban for at least two years; and YouTube has also frozen his account. While these three platforms have justified their removal of Trump from their platforms because of his incitement of the January 6 attack on the Capitol, the greatest effect of Trump’s banishment from social media has been in the interruption of his use of these platforms for the production of a sensibility of hatred, anger, fear, and violence through his incessant campaign of gore mediation. Perhaps there is a message here for those who seek to resist Trump’s bromantic admirer Jair Bolsonaro. If his regime of gore mediation is to come to an end, it may be less important for his opposition to focus its efforts in the streets or at the ballot box than on the disruption of his normalized sensibility of gore mediation on the screens of our computers, televisions, and personal mobile devices.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Erick Felinto is currently chair of the graduate program for media studies at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (PPGOCM-UERJ). He was the President of the Association for the Brazilian Graduate Programs in Communication (Compós) between 2007 and 2009 and has published six books in Portuguese, as well as several articles on media theory, film studies and comparative literature in English, French, Spanish and German. He was a visiting professor at NYU and Universität der Künste Berlin. In 2012 and 2015, he organized the series of International Symposiums “The Secret Life of Objects.”

Richard Grusin is Distinguished Professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where he directed the Center for 21st Century Studies from 2010–2015 and 2017–2021. He has published four books in English, including Remediation: Understanding New Media, with Jay David Bolter (MIT, 1999) and Premediation: Affect and Mediality after 9/11 (Palgrave, 2010). Two of his books have appeared in Italian: Remediation: Competizione e integrazione tra media vecchi e nuovi (Guerini, 2002) and Radical mediation: Cinema, estetica e tecnologie digitali, a cura di A. Maiello (Pellegrini, 2017). He has also edited five books: The Nonhuman Turn (Minnesota, 2015); Anthropocene Feminism (Minnesota, 2017); After Extinction (Minnesota, 2018); Ends of Cinema (Minnesota, 2020); and Insecurity (forthcoming Minnesota, 2022).

Notes

-

[1]

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) within the scope of the CAPES/PRINT program.

-

[2]

For more information on the Amnesty Law, see Alexandra McAnarney & Alexandra Montgomery: “Forty years ago, on August 28, 1979, Brazil’s Lei de Anistia (Amnesty Law) was passed, shielding all perpetrators of political crimes committed during the country’s 1964–1985 military dictatorship from prosecution. Passed by then-president General Joao Figuereido, the law initially provided a framework for national reconciliation. It allowed activists-in-exile the opportunity to return to Brazil. It also gave torture victims and political dissidents a means through which to defend themselves, negotiate their release, and clear their names.” “Brazil on the 40th Anniversary of the Amnesty Law,” Opendemocracy.net, 29 August 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/democraciaabierta/brazil-40th-anniversary-amnesty-law/ (accessed 30 November 2021).

-

[3]

Daniel Aarão Reis, “Ditadura, anistia e reconciliação,” Estudos Históricos, vol. 35, no. 45, 2010, p. 171–186, available at SciELO.br, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21862010000100008 (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[4]

“Pfizer enviando e-mails para Bolsonaro Meme Tente não rir,” ClipsEngraçados, YouTube channel, 11 June 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQR_baai6Ls (accessed 3 September 2021)

-

[5]

See the fascinating report Teitelbaum provides of Bannon’s dinner with Olavo de Carvalho and some dignitaries of the new Brazilian government right after the Brazilian elections: Benjamin R. Teitelbaum, War for Eternity: Inside Bannon’s Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers, New York, HarperCollins, 2020, p. 110.

-

[6]

Ibid., p. 168.

-

[7]

Sayak Valencia, Gore Capitalism, Cambridge, The MIT Press, coll. “semiotex(e),” 2018, p. 3.

-

[8]

Ibid., p. 187.

-

[9]

Richard Grusin, Premediation: Affect and Mediality After 9/11, New York, Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

-

[10]

Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, Durham, Duke University Press, 2019.

-

[11]

Richard Grusin, “Trump, La Terreur et La Médiation Totale,” L'Avenir des écrans, Jacopo Bodini, Mauro Carbone, Graziano Lingua & Gemma Serrano (éds), Paris, Éditions Mimésis, 2020, p. 223-238. It was translated by Marion Roche.

-

[12]

For instance, see Tom Phillip, “Trump of the tropics: the ‘dangerous’ candidate leading Brazil’s presidential race,” The Guardian, 19 April 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/19/jair-bolsonaro-brazil-presidential-candidate-trump-parallels (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[13]

Hanrrikson de Andrade, “Bolsonaro exalta Trump após EUA desclassificarem Brasil como emergente,” Notícias UOL, 11 February 2020, https://noticias.uol.com.br/internacional/ultimas-noticias/2020/02/11/bolsonaro-exalta-trump-um-dia-apos-eua-desclassificar-brasil-como-emergente.htm?cmpid (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[14]

Jean Paul Prates, “O malfadado namoro entre Donald Trump e Jair Bolsonaro,” Carta Capital, 6 December 2019, https://www.cartacapital.com.br/opiniao/o-malfadado-namoro-entre-donald-trump-e-jair-bolsonaro/ (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[15]

Renato Sérgio Lima, Paulo M. Jannuzzi, James F. Moura Junior, Damião S. de Almeida Segundo, “Medo da Violência e Adesão ao Autoritarismo no Brasil: Proposta Metodológica e Resultados em 2017,” Opinião Pública, vol. 16, no. 1, 2020, p. 34–65, available at SciELO.br, https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-0191202026134 (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[16]

See VVAA, “Steve Bannon e o verdadeiro Caixa 2 de Bolsonaro”, Todos com Ciro, October 2019, https://todoscomciro.com/news/caixa-2-bolsonaro-steve-bannon/ (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[17]

Victor Piaia & Marcelo Alves, “Abrindo a caixa preta: análise exploratória da rede bolsonarista no WhatsApp,” Intercom–RBCC, vol. 43, no. 3, September–December 2020, p. 137, available at SciELO.br, https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-5844202037 (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[18]

Andrew Chadwick, The Hybrid Media System. Politics and Power, [2013, online], Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017, coll. “Oxford Studies in Digital Politics.”

-

[19]

Piaia & Alves, 2020, p. 1378.

-

[20]

Erica Anita Baptista, Patrícia Rossini, Vanessa Veiga de Oliveira, Jennifer Strommer-Galley, “A circulação da (des) informação política no WhatsApp e no Facebook,” Lumina, vol. 13, no. 3, 2019, p. 29–46, https://doi.org/10.34019/1981-4070.2019.v13.28667 (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[21]

Piaia & Alves, 2020.

-

[22]

Teitelbaum, 2020, p. 171.

-

[23]

Ibid., p. 12.

-

[24]

Ibid., p. 14.

-

[25]

Angela Nagle, Kill all Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right, Winchester, Zero Books, 2017, p. 118. Not surprisingly, the historical associations between traditionalism and radical ideologies like fascism have been discussed by several scholars. For instance, Julius Evola, an Italian intellectual who had a very prominent role in the movement and whose books are bedside reading for Bannon, Carvalho, and Dugin, “was invariably featured as the intellectual inspiration of Far-Right terrorism in Italy during the so-called ‘years of lead,’ the 1970s, when machine-gun bullets had flown far more frequently than was healthy in a Western democracy” (Mark Sedgwick, Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 10). Italy has been a favorite location for Bannon, whose attempt to establish the Dignitatis Humanae Institute, a conservative Catholic political academy in a 13th century monastery south of Rome, which he has leased from Italy’s Culture Ministry, was upheld by an Italian regional court in May 2020.

-

[26]

See G1, “ 50% dos brasileiros são católicos, 31%, evangélicos e 10% não têm religião, diz Datafolha,” 13 January 2020, https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2020/01/13/50percent-dos-brasileiros-sao-catolicos-31percent-evangelicos-e-10percent-nao-tem-religiao-diz-datafolha.ghtml (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[27]

Valencia, 2018, p. 44.

-

[28]

Ibid., p. 45.

-

[29]

However, according to a report prepared by the National Committee of Truth (Comissão Nacional da Verdade, CNV) in 2014, at least 191 were murdered by the dictatorship and 243 simply “disappeared”.

-

[30]

Ribamar José de Oliveira Junior, “Capitalismo Gore no Brasil: entre farmacopornografia e necropolítica, o golden shower e a continência de Bolsonaro”, Sociologias Plurais, vol. 5, no. 1, 2019, p. 251, available at Revistas.ufpr.br, http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/sclplr.v5i1.68204 (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[31]

Ibid., p. 248. See also Marco Antonio Carvalho, “75% das vítimas de homicídio no País são negras, aponta Atlas da Violência,” Estadão, 5 June 2019.

-

[32]

Mbembe, 2019, p. 38.

-

[33]

Ibid.

-

[34]

Pedro Henrique Medeiros, “Olavo de Carvalho sobre Bolsonaro,” 21 February 2018, https://olavodecarvalhofb.wordpress.com/2018/02/21/olavo-de-carvalho-sobre-o-bolsonaro/ (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[35]

Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, Tübingen, Max Niemeyer, 1953, p. 134.

-

[36]

Raymond Williams, Preface to Film, London, Film Drama, 1954, p. 11.

-

[37]

See Richard Grusin, “‘Once more with feeling’–Trump, premediation, and 21st century terrorism,” Vanessa Ossa et al. (eds.), Threat Communication and the US Order after 9/11–Medial Reflections, London, Taylor & Francis, 2020, p. 99–114.

-

[38]

Kurt Braddock, Weaponized Words: The Strategic Role of Persuasion in Violent Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 224.

-

[39]

Greg Dickinson & Brian L. Ott, The Twitter Presidency: Donald J. Trump and the Politics of White Rage, London, Routledge, 2019, p. 3.

-

[40]

João Pedroso de Campos & André Siqueira, “Pesquisa exclusiva: Bolsonaro é o favorito da corrida eleitoral em 2022,” Veja, 24 July 2020, https://veja.abril.com.br/politica/pesquisa-exclusiva-bolsonaro-e-o-favorito-da-corrida-eleitoral-em-2022/ (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[41]

Pedro Henrique Gomes, “‘Não sou coveiro, tá?’ diz Bolsonaro ao responder sobre mortos por coronavírus,” G1, 20 April 2020, https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2020/04/20/nao-sou-coveiro-ta-diz-bolsonaro-ao-responder-sobre-mortos-por-coronavirus.ghtml (accessed 3 September 2021)

-

[42]

Sayak Valencia, Gore Capitalism, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2018, p. 18.

-

[43]

Several “favelas” (slums) of Rio are now dominated by militia that, under the excuse of fighting crime and the drug dealers, charge monthly “contributions” from residents and local businesspeople.

-

[44]

Something similar is now happening in Brazil, especially after former president Lula’s corruption charges were nullified by the Superior Court, thus making him eligible again. Bolsonaro and his supporters believe the 2022 election will be rigged unless Congress passes a new law requiring printed ballots instead of electronic votes.

-

[45]

Barton Gellman, “The Election that could break America,” The Atlantic, 23 September 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/11/what-if-trump-refuses-concede/616424/ (accessed 30 November 2021).

-

[46]

Richard Grusin, “Donald Trump’s Evil Mediation,” Theory & Event, vol. 20, no. 1, 2017, p. 86–99.

-

[47]

Dan Barry and Sheera Frenkel, “‘Be There. Will Be Wild!’: Trump All but Circled the Date,” New York Times, 30 January 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/06/us/politics/capitol-mob-trump-supporters.html (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[48]

Ibid.

-

[49]

Adam Shaw, “Trump promises ‘wild’ protest in Washington DC on Jan. 6, claims it’s ‘impossible’ he lost,” Fox News, 19 December 2019, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/trump-wild-protest-washington-dc-jan-6 (accessed 3 September 2021).

-

[50]

Marissa J. Lang, “Jan. 6 protests multiply as Trump continues to call supporters to Washington,” Washington Post, 30 December 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/trump-january6-dc-protest/2020/12/30/1773b19c-4acc-11eb-839a-cf4ba7b7c48c_story.html (accessed 3 September 2020).

-

[51]

Lauren Leatherby et al.,“How a Presidential Rally Turned Into a Capitol Rampage,” New-York Times, 12 January 2021.

List of figures

Figure 1

“Aqui quem fala é ela, a Pfizer,” meme created in June 2021, available at https://www.nsctotal.com.br/noticias/meme-pfizer-humorista-repercussao (accessed 2 December 2021).

Figure 2

“Presidente genocida,” meme, date of creation unknown, available at https://falauniversidades.com.br/memes-contra-bolsonaro-ganham-repercurssao-nas-redes-sociais-confira/, (accessed 2 December 2021).

Figure 3

Bolsonaro watches Trump’s speech, 8 January 2020, available at Gazetadopovo.com.br, https://www.gazetadopovo.com.br/republica/breves/bolsonaro-assiste-ao-discurso-de-trump-e-transmite-nas-redes-sociais/ (accessed 2 December 2021).

Figure 4

Figure 5