Abstracts

Abstract

This essay is the first dedicated solely to the work and archive of Ibrahim and Chalil (Khalil) Rissas (Rassas). Ibrahim was one of the pioneers of Palestinian photography in Jerusalem in the early twentieth century and Chalil, his son, was one of the first Palestinian photojournalists in the 1940s. Rissas’ images were looted and seized by Israeli officer from the photographers’ studio, from the body of a soldier or “slain Arab,” or “rescued” from a burning shop. Those photographs that had been looted from the studio, were the first collection I found in the Israeli military archives. In this essay I chart and analyze the way Rissas’ images were looted on several occasions and the moral, sociological, and political consequences of these acts—for instance how the looted object becomes a symbol of triumph or acts as a vehicle to dehumanize the enemy. The essay is also the first to focus on the phenomenon of pillage by individuals who transfer the looted cultural assets to colonial official archives where they are ruled by the colonial administration. It thus reflects not only the responsibility of states in the process of “knowledge production” and on their role in distorting the past and rewriting history by various bureaucratic, linguistic, and legal means, but also on the role of citizens in these destructive processes.

Résumé

Cet essai est le premier à se pencher exclusivement sur le travail et les archives d’Ibrahim et Chalil (Khalil) Rissas (Rassas). Ibrahim fut un des pionniers de la photographie palestinienne à Jérusalem au début du 20e siècle. Son fils Chalil fut l’un des premiers photojournalistes palestiniens dans les années 1940. Leurs archives ont été pillées et saisies, dans leur studio photo de même que sur la dépouille d’un Arabe, par des soldats israéliens. C’est la première collection que j’ai trouvée dans les archives militaires israéliennes. Tout au long de cet article, je retrace et analyse la façon dont elle a été pillée, et les conséquences morales, sociologiques et politiques de ce pillage; comme la transformation de ces objets volés en symboles de triomphe, ou en vecteurs de déshumanisation de l’ennemi. Il s’agit également du premier essai s’intéressant aux phénomènes de pillages dont les auteurs transfèrent les biens culturels saisis aux archives coloniales officielles, où ils tombent sous la responsabilité de l’administration coloniale. La réflexion ne porte donc pas uniquement sur la responsabilité des États dans le processus de « production de savoir » ou leur rôle dans la déformation du passé et la réécriture de l’histoire par divers biais bureaucratiques, linguistiques et légaux. Elle porte également sur le rôle des citoyens dans ce genre de processus de destruction.

Article body

Introduction

This essay is dedicated to the work and archive of Ibrahim and Chalil Rissas.[2] Ibrahim was one of the pioneers of Palestinian photography in Jerusalem in the first decades of the twentieth century. Chalil, his son, was one of the first Palestinian photojournalists in the 1940s. Twenty years ago, when I first found photographs by the Rissas Studio in the Israeli pre-state military Haganah Historical Archive (henceforth the Haganah Archive), the photographers and their work were unfamiliar. Their activities and photographic creation, especially those from the first half of the twentieth century discussed here, had been forgotten and have not been exhibited, discussed, or published since then—they had disappeared from the public sphere. Therefore, there was no information as to whether the photographers were still alive, who their relatives were, the importance of their work, or where their archives were located. During my research I discovered that much of the photographs had been looted from the Rissas’ store[3] by an officer, for his personal interest (and not for a military purpose), and that they are currently held at the Haganah Archive. A few other images from the Haganah Archive had been pillaged from a dead soldier on the battlefield. These images are accompanied by a caption written on a card at the archive: “Photographs found on an Arab prisoner,” whereas they were actually looted from a dead soldier, as I will further discuss. Another group of Rissas’ photographs at the IDFA, defined as “seized,” are held in files entitled “Arabs of Israel before 1948” or “Arab sources.” The first page of the file “Arabs of Israel before 1948” contains a legal text, probably by the censor/legal advisor of the archive: “Accepted since the 1967 mopping up operation. November 2002—There is an opinion by the attorney general to allow the use of seized materials.” One of the images held at the IDFA (Israel Defense Force and Defense Establishment Archives) was pillaged from the pocket of “a slain Arab,” as mentioned by the caption that accompanies the photograph. Rissas’ images were then handed over on various occasions to Israeli military archives and were declassified (opened) in 1998 (by the Haganah Archive) and in 2002 (by the Israel Defense Force and Defense Establishment Archives [henceforth IDFA]). According to Rissas’ relatives, most of the declassified visual materials in the Israeli archives are those of Chalil Rissas, although it is also possible that some of the photographs have been taken by Ibrahim Rissas. It is not clear whether Rissas’ photographs in the Haganah Archive and the IDFA have been provided by the same source (the officer who looted the store) and whether the pillaged images held at the Haganah Archive and the IDFA were taken from the same person/soldier. Despite the fact that photographs can be endlessly duplicated and distributed, additional copies of Rissas’ photographs, as far as I know, have rarely been found elsewhere.

However, it is only lately, on 9 December 2018, that I learned from an article in the Haaretz newspaper that additional photographs by Rissas Studio, Chalil (Khalil) Raad, and American Colony Photographers have been “rescued from a burning photography store in Jerusalem during the 1947–1949 War of Independence.”[4] Besides the fact that, as indicated in the article, “the store where the albums were found was in the city’s Mamilla neighbourhood” and that it “had been shelled and caught fire,”[5] the article/the archive/“the rescuer” does not reveal who was the photographer who originally owned the store. Information about the photographer and the original owner is missing in the article, even concealed, and the looting is described with soft terms, as a “rescue”[6] from the flames, while in reality the photographs have been stolen after a fire in the store. In addition, the article does not discuss the question of why the photographs have not actually been restored to their owner as they should have been. One can learn from it that many images by Rissas (and other Palestinian photographers) were looted and seized, and hopefully in time they will be open to the public or even returned to their owners[7]—and to Palestinian history. As a result, Rissas’ photographs have fallen into oblivion. Furthermore, since my publication of their work[8] they have not been researched by other scholars or curators. There are probably other images by Ibrahim and Chalil Rissas currently in Israel’s archives, but access to them is restricted.

Over the years, I have published, in edited and thematic books and essays in Hebrew, English, and Arabic, research on, among others, the Rissas Studio in relation to the Israeli colonial seizure and looting of cultural artifacts as acts of cultural cleansing. In addition, I have studied the work of Ibrahim and Chalil Rissas in relation to the history of Palestinian visual resistance and the history of Palestinian photography.[9] This essay, the first in English dedicated solely to Rissas’ life and work, summarizes some of the research I have conducted and includes new findings. However, further research into this topic is still required.

The State of Israel was established in 1948, resulting in the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe. Most of the Palestinian population fled the country or was expelled, and their return was denied by Israel. In March 1950, the state of Israel legislated the Absentee Property Law,[10] according to which Palestinian properties and goods were nationalized and passed into the hands of the Custodian of Absentee Property (section 4), designed to prevent Palestinian refugees from returning and claiming their properties and goods. At the same time, libraries and cultural treasures, as well as other goods, were seized before, during, and after the war by organized military groups or looted by individuals for personal gain. Once seized, by intelligence corps, the cultural assets were usually transferred to intelligence units and then to military archives where they were censored by the archive upon their arrival. Since then they are concealed from the public sphere, through a sophisticated system of repression and regimentation, thus erasing their original identity and replacing it with that of the occupier.[11] These archives, like the Custodian of Absentee Property, function as official colonial agents of cleansing of cultural assets. The essay thus expands on my research on the looting/pillage of Palestinian cultural artefacts by individuals (inhabitants or soldiers not in duty), which is different from the deliberate seizure of cultural and historical treasures by pre-state Jewish military organizations and Israeli military bodies and soldiers in duty, which I have discussed more extensively in previous publications.[12] Similarly to seized archives/items, many of the pillaged cultural items are transferred by individual looters to these official colonial military archives and subjugated to the same repressive system of management and control. The essay will focus on this phenomenon: the looting by individuals and transfer of the theft to official military archives in Israel.[13] Therefore, cultural cleansing and the use of force against native archives occur on two levels. First, on a physical level, looting and seizure, which could be understood to be on par with other physical human rights violations against indigenous people, such as rape, torture, theft, and dispossession of land. Second, on the level of consciousness, as colonial management carried out through archival mechanisms and sites of “knowledge production”:[14] subjugating Palestinian archives to Israeli law; burying these materials and hiding them from the public sphere; having control over what materials will be declassified (if declassified) and which researchers will be given access to them; charging the looted archives with new interpretations; cataloguing them according to the colonizer’s norms, procedures, and terminology; and claiming ownership.[15]

This essay thus serves as a case study on the subject of pillage and charts the chain of events and various forms of control imposed on the looted object: from the original owner to the looter, to the official archive where it is governed by colonial laws and procedures.

Rissas’ work is particularly important to me since it was the first collection of looted photographs that I found in Israeli archives managed by a colonial administration.[16] I realized that Rissas’ looted archive is part of a broader phenomenon of theft of cultural archives/objects, and I started searching systematically for additional plundered or looted archives in Israel’s possession. Due to this research I was able to follow the genealogy of seizure and control over Palestinian treasures by official bodies. Although I succeeded in tracking various archived cultural assets, I believe that many are still classified. Until Israel opens all the archives it holds, it is impossible to evaluate the range of materials held in Israeli official archives.[17]

Pillage: Legal and Theoretical Aspects

International law distinguishes between pillage by individuals (such as civilians or soldiers) for personal intent (in many cases treated as “souvenirs” taken from the battlefield or the war zone) and seizure by organized official forces. Seizure, or the taking of war booty, relates to property seized from individuals and public institutions within the framework of official state military activities in a planned and conscious manner.[18] Pillage of cultural property by individuals in armed conflict zones is the violent and unauthorized taking of public or private property for personal gain, whether such property belongs to individuals, communities, or the state.[19] The looting of belongings of killed soldiers on the battlefield, belongings that reflect the soldier’s “private identity as a human being,”[20] also constitutes pillage of personal cultural-historical items. Guido Carducci demonstrates that international laws prohibit pillage in both occupied and non-occupied areas in regions where armed conflicts unfold. However, these laws generally do not do more than prohibit. For example, they do not provide, beyond a legal definition, a set of sanctions specific to acts of pillage in case of breach of this prohibition.[21]

International laws prohibit both pillaging by individuals and organized seizure by military bodies. The 1899 Hague Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, replaced by the Hague Convention of 1907,[22] forbids pillage, seizure, destruction, or damage: “Private property cannot be confiscated”[23] and “Pillage is formally forbidden.”[24] It states that public property (such as state and municipal property, as well as the property of institutions dedicated to religion, charity, education, the arts and sciences), “shall be treated as private property. All seizure of, destruction or willful damage done to institutions of this character, historic monuments, works of art and science, is forbidden, and should be made the subject of legal proceedings.”[25] The prohibition of pillage is applicable to all types of property; however, it leaves the right of states to seize in cases where such seizure is “imperatively demanded by the necessities of war,”[26] otherwise it is defined as a war crime.[27] As mentioned before, Rissas’ photographs were said to have been looted from the belongings of a soldier/ a “slain Arab,” from Rissas’ studio, and from a burning shop; they haven’t been returned to their owner (or their relatives) and have remained in the official archives: all this constitutes pillage of personal and cultural-historical items according to the international laws. The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict[28] urges all parties “to respect cultural property” and “to prohibit, prevent and, if necessary, put a stop to any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property.”[29]

The looting of goods has been largely discussed, especially the act of pillaging for private gain by soldiers from other soldiers on the battlefield, for instance, during World War I[30] and World War II.[31] Simon Harrison demonstrates that pillage of personal items from the enemy dead is perceived as “hunting,” or “souvenir hunting”: “This powerful metaphor of the war as a hunt or hunting expedition created expectations that servicemen would bring home trophies, tangible evidence of success.”[32] The pillaged items sometimes are given as a gift or are sold to a third party, but they always glorify the looters in their home countries. Such items not only provide proof that the soldiers have indeed been on the battlefield, but serve as “evidence of victory and instruments of memory.”[33] Konstantin Akinsha shows, for example, that although officers from the 38th Field Engineers’ Brigade of the Red Army looted drawings, paintings, and prints from the collection of the Bremen Kunsthalle during World War II, after their return to the USSR, some of the officers transferred the looted items to different museums in the Soviet Union. Over the years, Russia refused to return these looted cultural properties, as they symbolized its victory in the war.[34] Furthermore, as the looted items are seen as physical proofs and symbolize military triumph on both personal and collective level, they also reflect military violence: “inheriting these objects also means inheriting the histories of violence that haunt them.”[35] Akinsha, shows, for example, that over time, the pillaged objects taken by Red Army soldiers became symbols of war violations and other crimes of the Stalin regime.[36] Researchers also argue that taking “souvenirs” from the dead bodies of enemy soldiers on battlefields during wars, for instance World War II, serves mainly as an act of dehumanizing the enemy.[37]

The looted artefacts undergo, as Harrison shows, a “radical change in meaning” over time.[38] He believes that the only level on which their meaning remains constant is “the bodies of the soldiers who once carried them,”[39] i.e. that the looted objects symbolize their owner’s body. Susan Stewart claims that “the memory of the body is replaced by the memory of the object,” and that the object refers mainly to its possessor, not to its maker.[40] Thus, while the object/item represents the body of the person who originally carried it, in the looting process this representation is altered and the object begins to accumulate memories. While the object symbolizes first the original owner, it then signifies the looter, and finally, the archive of looted objects (i.e. the colonizer). Moreover, building on Susan Pearce’s claim that souvenirs are both symbols of the past and the present,[41] I argue that the past is symbolized by the original owner—the photographer, the possessor, the exiled owner, the dead soldier. The present is symbolized by the current possessor[42]—the looter (whether a soldier, a civilian, or an archivist) and those currently in power. The latter mark ownership over the object by various means, such as adding stamps of ownership or writing on the items. The looted objects, thus, may undergo a metamorphosis: from telling the story, history, and culture of the missing original owner and the contents of the original object, to describing the process of colonization.

Fig. 1

A photograph showing the front entrance to the Rissas Studio. A hand-written text in Hebrew at the bottom of the photograph reads: “The store where these pictures were photographed and from where they were ‘pilfered’.”

Photo Rissas: Ibrahim and Chalil Rissas

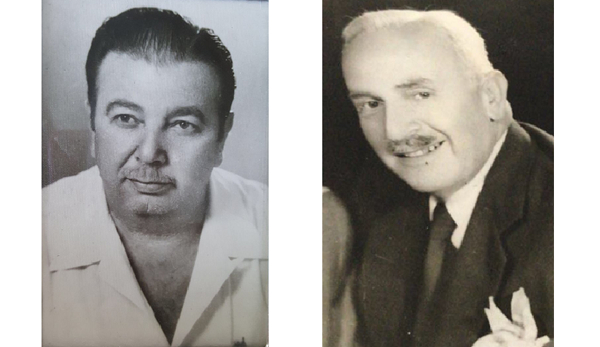

Fig. 2‒3

Portraits of Chalil Rissas (on the right) and Ibrahim Rissas (on the left).

Fig. 4

The beginning of Palestinian photography[43] can be marked, in general, with the work of Chalil Raad in 1891 in Jerusalem, and a year later with the early work of Daoud Saboungi[44] in Jaffa. A study of Raad’s work—parts of which were looted, while others were rescued by members of his family—reveals that he travelled throughout Palestine and the Middle East photographing a wide range of subjects, such as families, events, weddings, children, portraits, landscapes, industry, agriculture, architecture, and archeological excavations. In the 1920s another generation of photographers emerged, such as Fadil Saba as well as Karimeh Abbud, the first female Palestinian photographer[45] who defined herself as “a national photographer.”[46] Hanna Safieh, Ibrahim Rissas, and Ali Za’arur also started to work in the 1920s, although their most significant work developed later.[47] Like Raad, they photographed daily life in Palestine and until the mid–1940s Palestinian photographers were primarily involved in studio/portrait photography, family photography, commercial photography, documentary photography, landscape photography (which sometimes included people), or images produced for local and foreign photography agencies.[48]

With the intensification of the national conflict[49] just before the Nakba of 1948, there was a major change in the subjects covered by Palestinian photography, giving rise to Palestinian photojournalism. While Za’arur and Chalil Rissas were among the first to give voice to the Palestinian resistance, military fights, and the consequences of the Nakba, and the first to present the Palestinian visual narrative from their own point of view, Hrnat Nakshian gave voice to the effects of the Nakba. This change in the character of Palestinian photography and representation is significant since, as far as it is known, earlier uprisings (in 1921, 1929, 1933, and 1936) have been very little documented by Palestinian photographers.[50]

Chalil Rissas (see Fig. 2) was born in Jerusalem in 1926, the first son in a family of ten children. His father, Ibrahim Rissas (1900–1971) (see Fig. 3), was a self-taught photographer and one of the first Muslim photographers in Palestine working in the region of Jerusalem. Ibrahim Rissas was a member (part of the management committee) of the Union of Arab Photographers of Jerusalem and Vicinity, which was established in December 1944 by several Palestinian photographers “to protect the photographers’ interests and to improve their standards of workmanship.”[51] This reflects Ibrahim's position in the photographer's community of Jerusalem.

Studio Rissas (for the studio’s logo, see Fig. 4) was located in the Bab al-Khalil region (also known as Hebron Gate in Arabic and Jaffa Gate in English and Hebrew), in an area where other non-Jewish photographers also had their shops, among them: Chalil Raad, Garabed Krikorian,[52] Miltiades Savvides (located outside the Jaffa Gate), and American Colony Photographers (inside the Jaffa Gate), thus forming an important centre for the visual documentation of Palestinian history (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Jerusalem (El-Kouds). The Jaffa Road, main thoroughfare of the new city, c. 1898–1914. Raad and Savvides’ studios are visible on the right side of the road and Krikorian’s studio on the left.

Ibrahim Rissas was mainly a studio photographer—he practiced portrait and family photography and developed films and printed photographs in his studio. Chalil, who studied photography with his father, chose the active side of photography. He was young, adventurous, and daring, and joined the Palestinian resistance forces (especially those of Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini) in Jerusalem and in the surrounding region and mountains. A study of Chalil’s looted photographs shows that he was on the front lines in high-risk areas and photographed the battles and warfare. He gave voice to the Palestinian struggle in Hebron and throughout the Jerusalem region and developed a new visual documentary language. He can therefore be considered as one of the pioneers of Palestinian photojournalism (see Figures 6 and 7).

Fig. 6

The text accompanying the image reads: “Arab Gang—parade, 1947–1948.” The Palestinian flag is visible on the right. As catalogued in the archive, the photograph (a part of a larger group of images) has been “accepted since the 1967 mopping-up operation.—November 2002—there is an opinion by the attorney general to allow the use of seized materials.”

Fig. 7

The text accompanying the image reads: “Arab Gangs in the Jerusalem Mountains,” 1947–1948. The image portrays Palestinian Commander Abed Al-Kader Al-Hussaini with his assistants and guards.

Fig. 8

Chalil Rissas photographed in Palestine until 1954 mainly for the Associated Press (AP) and the Egyptian magazine Alhilal as well as for newspapers such as The Palestine Post, focusing on event photography and news. After his marriage in the same year he moved to Saudi Arabia for economic reasons where he continued working as a photographer. He returned to Jerusalem in 1956 to join his father in his studio (see Fig. 8 for a later portrait of Chalil Rissas from that time). In 1967 they relocated the studio to Al-Zahara Street, another area with many photography stores. Ibrahim and Chalil received authorization to photograph tourists at the Al-Aqsa Mosque and they did so from 1959 to the early 1970s (Ibrahim died in 1971 and Chalil in January 1974 from a heart attack). Chalil’s youngest brother, Waheeb Rassas, continued this line of work until his death in 2010.

In the mid–1940s, in the period when Chalil Rissas started working, another photographer, Ali Za’arur (1901–1972), also gave voice to the Palestinian and Arab struggle. Za’arur was born in Al-’Azariya and learned photography in the late 1920s and early 1930s from a photographer by the name of Hannaniah. In the early years, he photographed mainly for the British, and between 1942 and 1945 he worked for them in Gaza. When he returned to Jerusalem in 1946, and until his death, he worked as a news photographer for AP and as a freelancer, capturing in his work in the late 1940s the physical struggle over the land.[53] The body of work that he has left[54] shows that Za’arur focused mainly on documenting the battle for the Old City of Jerusalem, from December 1947 to December 1948. His photographs depict the battle of the Arab Legion and the Nakba experienced by the Palestinians.

What makes Za’arur’s and Chalil Rissas’ work unique is that it presented for the first time from a Palestinian perspective the Battle for the Old City of Jerusalem in 1948 (especially in the Jewish section) and the area around Jerusalem and Hebron, which Rissas documented. Until 2000, when I first published the work of Za’arur and Rissas, the Battle for Jerusalem had been depicted mainly in two types of documentation: photographs by the Welsh photographer John Phillips and a reconstruction of the Battle as described by Jack Padwa in the film Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer (Thorold Dickinson, 1955), produced with IDF assistance. Both chronicle the Israeli narrative. Za’arur’s and Rissas’ photographs of the Battle reveal documentation of this historical period from a new and previously unknown point of view—the indigenous perspective.[55]

Colonial Administration

The first photograph I found that testified to the looting and plunder was an image of Rissas’ Studio in the Haganah Archive (see Fig. 1). It bore a hand-written caption (in Hebrew): “The store where these pictures were photographed and from where they were ‘pilfered’.”[56] The softened term “pilfered” is terminology used by the colonizer to blur the act of looting and plunder. The archival methods and the terminology used to catalogue Rissas’ entire work reflect the same strategy of “cleaning” the language from the negative connotations that the act of plunder carries. In the Haganah Archive's catalogue, some of the looted images are described as “found”: “The photograph was found in the Rissas Studio, Jerusalem” (see Fig. 2).[57] The use of “innocent” words such as “found” and “pilfered” (or “rescued,” as shown above) not only demonstrates that the colonizer blurs the act of looting and the use of plundered material, but it also exposes the immorality of the colonizer’s actions.

In order to describe the transformation in the way the looted materials are signified over time “from past to present,” and to describe the way power is enforced by the looter, I developed a research method to study plundered archives, visual materials, and images. I first search for information on the looted material with regards to the photographer as well as the archive, the historical, cultural, political, and ideological character of the material and its rightful owner (which is usually concealed by the colonizer). I then focus on charting a map of the looting by locating the citizens and/or soldiers who looted or seized the archive or witnessed such looting. I proceed to describe the physical forces imposed on the cultural assets: from the looters and the act of looting to the way the materials are managed by the looters—whether the objects are kept in private hands, sold as commodity,[58] or transferred as “gifts” to family members or to an official institution. In the last stage I track the mechanisms of force that colonial archives apply in the governing of looted material, which could encompass acts of censorship, classification, concealment, cataloguing according to the colonizer’s terminology, and taking ownership over the material according to the colonizer’s laws, norms, and procedures. This includes deciphering the countless layers, overt or covert, of the colonizer’s archives and exposing its well-constructed system of camouflage and erasure.

The first set of photographs I found in the Haganah Archive was looted from Rissas’ studio by an officer in the Israeli army who took them out of personal interest and not for information or military purposes. On his return from the war he gave them as a gift, a “souvenir,” to his son who later forwarded them to the official Israeli archive.[59] These Palestinian images, although not produced by Israeli institutions or photographers or for Jewish/Israeli objectives[60]—which is one of the main criteria for a material to be included in the Israeli military archives—were stored in these archives, subjected to Israeli laws, censored for five decades, and sentenced to silencing and erasure.[61] The second set of photographs, found in the IDFA, are defined by the archive as “material taken as military booty.” Therefore, it is not clear whether the images reached the archive from the same source (the officer who pillaged the photographs from the studio) or through an organized seizure by military forces. In 2002, according to the archival records, and as shown above, the legal advisor to the Israeli Ministry of Defense allowed access to Rissas’ photographs, which until then had been classified. The archive records also reveal that they were saved from elimination in 1967.

Shortly after the looting, the first set of photographs from the Haganah Archive was sent by the officer’s son to the Israeli military magazine Bamahane in order to increase their exposure, while emphasizing the power of the victorious. Through an announcement on the army radio station Galei Tzahal, the magazine had appealed to the general public to send photographs of the war.[62] Rissas’ photographs were published in June 1949 in two successive issues of Bamahane, under the title “Pictures and the Hidden through Arab Lenses (Imprisoned Photographs).”[63] An analysis of the text accompanying the photographs as published in the magazine, such as “imprisoned photographs,” shows that when the capture of cultural materials is “part of a single drive to conquer,”[64] power is cast over the looted objects. The colonizer changes the original meaning of the images, loading them with content contrary to their original essence. This is a language of bias, indicating Israel’s fear of a narrative that contradicts its own or that threatens to crack its worldview. Hence, the caption of one of the photographs published in Bamahane on 9 June 1949, depicting Palestinians standing on the ruins of a house, reads: “In a daring attack a team of Haganah fighters enters Arab territory, the well-known Semiramis Hotel was bombed and destroyed along with its occupants: gang leaders and organizers. The confused and defeated Arabs stand on piles of rubble.”[65] The caption describes the “daring” operation of the Jewish Haganah fighters, while the Palestinian and Arab fighters are described as “gangs” (for examples of other uses of the word “gang” to describe such images, see Figures 6, 7, and 9). The article also depicts them at their lowest moment, standing “confused and defeated […] on piles of rubble.”[66] These photographs were therefore used, as Margaret Higonnet shows and as described above, as evidence of the Israeli triumph and as instruments of remembrance of those in power.[67]

Fig. 9

The text accompanying the image reads: “Arab Gang Marching” (depicted on the left is Abed Al-Kader Al-Hussaini and on the right is probably Kazem Rimawi), 1947–1948.

Clearly, Rissas, who was devoted to the Palestinian cause, did not take his photographs in order to depict the Israeli perspective; the magazine changed the meaning of the images to match the Israeli viewpoint, contrary to the photographs’ original intent. There is another example from 1951: the army station had a program called In Tomorrow’s Bamahane, which usually reviewed the magazine’s issue to be published the following day and commented on previous issues. In a broadcast from 16 May 1951, the host of the program referred to the article “The Road to Independence, the Jerusalem War, Photographs from the Arab Side”[68] (see Fig. 10). The article is based on Rissas’ looted/seized photographs and does not mention the name of the photographer nor attributes copyright to him, even though the name of the photographer was known (see below). It states: “In the series of photographs, the Arab war against the Jews in Jerusalem is shown for the first time. The photographs, taken by an Arab photographer, who moved freely in the Arab areas, fell into Jewish hands during the later stages of the war over Jerusalem.”[69] The article also dedicates space to Abd al-Qader al-Husseini’s resistance, which Rissas documented. The back side of Rissas’ images in the Haganah Archive include stamps of both Studio Rissas (the photographer, i.e. the original owner/copyright holder) and the military archive (see Fig. 11). Thus, the contents/memories of the original and indigenous owner are replaced by those of the colonizer. Israel is asserting ownership on the pillaged items, however, the traces of the original owners are still present and cannot be concealed or forgotten.

Fig. 10

Two-page spread from the 10 May 1951 issue of Bamahane. The photographs were published as part of an article entitled “The Road to Independence, The Jerusalem War, Photographs from the Arab Side.”

Fig. 11

Visible on the back of one of Rissas’ photographs is a stamp of Studio Rissas in Arabic and English as well as the stamp of the Haganah Archive in Hebrew.

The radio host encouraged the public to continue sending photographs from their personal albums and referred to the published images in the following way:

Recently, after a break, Bamahane brought back the program There Were Days, the same program that posts pictures sent to Bamahane by its readers, pictures that, from time to time, bring back old, yet fresh, memories—the struggle for our independence, the struggle for Hebrew arms, for an independent Hebrew force, memories of the beginning of the Independence War […]. Bamahane will be grateful to everyone who sends us these pictures… for many of us, these memories are hidden between album pages, in drawers, envelopes, among various papers, in jacket pockets, or in a notebook.[70]

The text uses Zionist terminology—words such as “independence,” “Hebrew arms,” “Independent Hebrew force,” and “liberation.” Although these photographs originally served to portray Palestinian heroism and the intensity of the Palestinian struggle, and although the original intentions of the photographer (who, at the time these images were published, was still active in Jerusalem) were different from those expressed in the publication, not a shred of that intent remains in the Israeli magazine. In contrast, the edition of the Arab magazine Almaswar [The Photographer], which was published in February–March 1948, used pictures by various photographers (Rissas among them) to describe the Palestinian resistance. It published a photographic essay of the Palestinian resistance in Safed, Tul Karem, Nablus, and the Jerusalem region, portraying the movement in a sympathetic light. The magazine also devoted space to the history of the Palestinian struggle, for example, it featured photographic work to illustrate Fawzi al-Qawuqji and his group who in 1936 fought against the British and against the Jews. There are also photographs by Rissas documenting military operations and training as well as the destruction of Jewish buildings on Ben Yehuda Street in Jerusalem in 1948 (the images, also held by the IDFA and the Haganah Archives, are part of the same series published in Bamahane and discussed above). The article gives significant importance to these photographs and to their creators’ original intent: to glorify the images and actions of Palestinian fighters.

Fig. 12

The text accompanying the image reads: “The Commercial Center in Jerusalem, 1947–1948.” “The photograph was found [among the belongings of] an Arab prisoner. Received from Rashkes Moshe.” Rashkes, however, contradicts this version by asserting that the photograph was taken from the dead body of an Arab soldier.

Another group of photographs by Rissas in the Haganah Archive has the caption: “Photographs found on an Arab prisoner.”[71] These images (for an example, see Fig. 12) were transferred to the Haganah Archive by Moshe Rashkes, a squad commander in the pre-1948 Jewish military organization Palmach in the region of Jerusalem, who described how they pillaged these photographs: “[F]rom the pocket of a dead Arab, in Sha’ar Hagai, Bab Al-Wad, in the beginning of May 1948. I was commander […] and we were looking for intelligence.”[72] In a book that Rashkes published with the IDF Ma’arachot publishing house he depicts the looting of images:

We started off at a fast pace, our load [the body] swinging […]. The corpse was turned to the rear as if pulled down to earth by a hidden weight. It was slipping from my hands and slowly sliding down, while I fought with all my strength to raise it back up […]. We approached the edge of the fence [the camp] and were relieved to drop the body at last […]. We bent over the body […] and began to rummage through the pockets of the blood-soaked clothing […]. The sight of the blood sticking to my fingers was nauseating […] we began to move our hands over the length and width of the body, turning it over in order to search it.[73]

Furthermore, Rashkes testified in an interview that: “We then found some photographs.”[74]

Conclusion

This essay deals with the moral, political, social and cultural aspects in the act of looting and with the radical way the meaning and use of the pillaged items are reformed over time. It shows that in contrast to the colonizer’s mechanisms of reinterpretation and concealment, they became symbols of war violations and crimes. Wendy Kozol, who studies photography albums pillaged from soldiers during World War II, argues that looking towards the looting and the looted items is important, because looking away would give credibility to the claim that these objects “are so exceptional, beyond the standards of representational decency, that we cannot study or critique them.”[75] This essay claims that in Israel, where this kind of looting is a common phenomenon, not only states and official colonizers should take responsibility for their role in the process of “knowledge production” and in distorting the past and rewriting the history of indigenous populations by various bureaucratic, linguistic, and legal means, but individuals—citizens as well as soldiers—should also face their roles in these destructive processes and take accountability. This “model of a violent power relationship between people”[76] includes pillage of dead people’s belongings that “generate estrangement, and ‘produce’ a category of people as enemies with whom to fight.”[77] It also includes looting from public and private sources, which aims to, among others, reflect the victory of the conqueror and emphasize the power relations between the looter and the one who was looted. Furthermore, individuals collaborating with the colonial acts of concealing history are casting images of indigenous peoples as terrorists, as the enemy. By doing so they block any chance of respecting and learning the past of the indigenous people, and any chance for a sane future. Therefore, I believe it is essential to expose and chart this process, from the moment cultural or personal objects are "hunted" for personal gain and become social norms and until they are used for colonial aims, regulated by museums, “imprisoned” in official archives, or buried in private homes.

Appendices

Biographical note

Dr. Rona Sela is a curator and researcher of visual history and art, and she teaches at the Tel Aviv University. Her research focuses on the visual historiography of the Palestinian–Israeli conflict, the history of Palestinian photography and colonial Zionist/Israeli photography, colonial Zionist/Israeli archives, archives under occupation, seizure and looting of Palestinian archives and their subjugation to repressive colonial mechanisms, visual representation of conflict, war, occupation, exile, immigration, and human rights violations, and on constructing alternative postcolonial mechanisms and archives. She has also conducted research on the development of alternative contemporary visual practices connected to civil society that seek to replace the old Israeli gatekeepers. She has published many books, catalogues, and articles on these topics and curated numerous exhibitions. Her first film is entitled Looted and Hidden—Palestinian Archives in Israel (2017, film-essay). For further information, visit http://www.ronasela.com.

Notes

-

[1]

I give special thanks to the Rassas family for supplying the necessary information for this essay, for providing me with family photographs, and for allowing to use the photographs. I am grateful for their assistance. Various parts of this essay were originally presented at the conference “Empire and Colonial Art,” 6–7 April 2017, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal.

-

[2]

The information about Chalil and Ibrahim Rissas is from meetings and conversations with their family members, conducted in 1999, 2000, and 2017, and from the following: Rona Sela, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Photography in Palestine in the 1930s & 1940s], Tel-Aviv, Hakibutz Hameuchad Publishing House and Herzliya Museum, 2000 (for the English translation of the chapter on Palestinian photography, p. 163-176, see: https://www.academia.edu/36679969/In_the_Eyes_of_the_Beholder_-Aspects_of_Early_Palestinian_Photography (accessed 30 July 2018); Rona Sela, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Made Public—Palestinian Photographs in Military Archives in Israel], Tel Aviv, Helena and Minshar Gallery, 2009; and Rona Sela, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Made Public—Palestinians in Military Archives in Israel], Ramallah, Madar Center—The Palestinian Forum for Israeli Studies, 2018. In Arabic, Khalil Rassas’ name is written [voir PDF pour traduction]. However, the English transliteration of his name, written on the storefront of his studio (see Fig. 1) and on other items, is “Rissas” (or “C. Rissas”) and this is the transliteration I use here. I encountered the problem of transliteration from Arabic to English and Hebrew at an exhibition of Chalil (Khalil) Raad who wrote his name in Hebrew and English differently from the academic transliteration. I usually use the photographers’ own spelling of their names.

-

[3]

After 1948, the area where Rissas’ store was located became a no-man’s land.

-

[4]

Nir Hasson, “Hundreds of Photos Found from When Israel’s War of Independence Raged,” Haaretz, 9 December 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-hundreds-of-photos-found-from-when-the-1948-war-raged-1.6725444 (accessed 11 January 2019). It was originally published in Haaretz in Hebrew on 7 December 2018 with the title [voir PDF pour traduction] https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-hundreds-of-photos-found-from-when-the-1948-war-raged-1.6725444 (accessed 11 January 2019).

-

[5]

Ibid.

-

[6]

Rona Sela, “Israel’s Art Scene Is Whitewashing the Nakba,” Haaretz, 28 December 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-s-art-scene-is-whitewashing-the-nakba-1.6787625?=&ts=_1546161547278 (accessed 11 January 2019). The article was originally published in Hebrew in Haaretz on 13 December 2018, [voir PDF pour traduction] https://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/art/exibitions/.premium-1.6743604 (accessed 11 January 2019).

-

[7]

Such as, for example, Ali Za’arur’s photographs, which were not looted or seized, but were returned to their owners by the IDFA upon the family’s request. See Rona Sela, “Ali Za’arur: Early Palestinian Photojournalism, the Archive of Occupation and the Return of Palestinian Material to Their Owners,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 74, 2018.

-

[8]

I first published their work in Sela, 2000. See also Sela 2009, 2018.

-

[9]

My book Photography in Palestine in the 1930s &1940s (2000) was the first study to deal with the political, national, and social aspects of both Zionist and Palestinian photography during that period and that charted the discipline from the late nineteenth century to 1948. It was also the first study to expose the looting and taking of booty (however, I did not research at that time the theoretical and legal aspects of the pillage and the seizure). For further research on this topic, which I have conducted over the years, see Sela, 2009 and Rona Sela, “The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure—Israel’s Control over Palestinian Archives,” Social Semiotics, vol. 28, no. 2, 2018, p. 201–229, published online, 3 March 2017, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10350330.2017.1291140 (accessed 19 June 2018).

-

[10]

For the full text of the law, see 1950 – [voir PDF pour traduction] https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/Law01/313_001.htm (accessed 13 February 2019).

-

[11]

Sela, “The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure,” 2018; and Rona Sela, “Rethinking National Archives in Colonial Countries and Zones of Conflict,” Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, in Anthony Downey (ed.), London, IB Tauris, 2015, p. 79–91. It was first published in Rona Sela, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Reality Trauma and the Inner Grammar of Photography], in Deuelle Luski Aim (ed.), Tel Aviv, Shpilman Institute for Photography, 2012, p. 49–67.

-

[12]

Sela, 2009; Sela, “Ali Za’arur,” 2018; Sela, “The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure,” 2018. See also Rona Sela, “Seized in Beirut—The Plundered Archives of the Palestinian Cinema Institution,” Anthropology of The Middle East, vol. 12, no. 2, 2017, p. 83–114 as well as my movie Looted and Hidden—Palestinian Archives in Israel, 2017, 46 min. 10 sec., https://vimeo.com/213851191 (accessed 29 July 2018). See also Amit Gish, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Ex-Libris: Chronicles of Theft, Preservation, and Appropriating], Tel-Aviv, Hakibutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 2014.

-

[13]

In contrast to pillaged archives/materials kept in private hands (see Sela 2000, p. 163–178).

-

[14]

Ann Laura Stoler, “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance,” Archival Science, vol. 2, no. 1‒2, 2002, p. 90–91. Many other studies deal with the state’s system of concealment and knowledge production: Lawrence Dritsas and Joan Haig, “An Archive of Identity: The Central African Archives and Southern Rhodesian History,” Archival Science, International Journal on Recorded Information, vol. 14, no. 1, 2014, p. 35–54; Caroline Elkins, Britain’s Gulag, The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya, London, Jonathan Cape, 2005; Gregory Rawlings, “Lost Files, Forgotten Papers and Colonial Disclosures: The ‘Migrated Archives’ and the Pacific, 1963–2013,” The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 50, no. 2, 2015, p. 189–212; Ann Laura Stoler, “Archival Dis-Ease: Thinking through Colonial Ontologies,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2010, p. 215–219; Todd Shepard, “‘Of Sovereignty’: Disputed Archives, ‘Wholly Modern’ Archives, and the Post-Decolonization French and Algerian Republics, 1962–2012,” The American Historical Review, vol. 120, no. 3, 2015, p. 869–883; Kirsten Weld, Paper Cadavers: The Archives of Dictatorship in Guatemala, Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 2014.

-

[15]

Sela, 2000, 2009; 2018, Sela, “The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure,” 2018; Sela, “Seized in Beirut,” 2017; Sela, “Ali Za’arur,” 2018; and Rona Sela, “Palestinian Materials, Images and Archives held by Israel,” Swiss for Peace (a practical study), 2018.

-

[16]

Sela, 2000; 2009; Sela, “The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure,” 2018.

-

[17]

Although I have tracked down various Palestinian archives, to date I have not succeeded in receiving a comprehensive list of the looted archives from the IDFA. All my requests to the IDFA were denied. With regards to pillaged materials that are in private hands, there are not estimations as to what was looted, as many of the archives are concealed by the looters in their homes. See, for instance, Sela, “Israel’s Art Scene,” 2018.

-

[18]

Jose Doria Jose, Hans-Peter Gasser, and M. Cherif Bassiouni, “The Legal Regime of the International Criminal Court,” International Humanitarian Law Series, vol. 10, 2009, p. 521–529, https://brill.com/view/title/11778 (accessed 20 October 2018).

-

[19]

Yoram Dinstein, The Conduct of Hostilities under the Law of International Armed Conflict, Cambridge, UK, 2004, p. 214; Guido Carducci, “Pillage,” in Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, 2009, http://opil.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e377 (accessed 24 June 2018).

-

[20]

Simon Harrison, “War Mementos and the Souls of Missing Soldiers: Returning Effects of the Battlefield Dead,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 14, no. 4, 2008, p. 774–790, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.00530.x (accessed 11 January 2019).

-

[21]

Carducci, 2009.

-

[22]

International Peace Conference, The Hague Conventions of 1899 (II) and 1907 (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000001-0247.pdf?loclr=bloglaw and https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000001-0631.pdf (accessed 24 June 2018).

-

[23]

The Hague Convention of 1907 (IV), Article 46.

-

[24]

Ibid., Article 47. The Geneva Convention of 1949 omitted the word “formally” in order not to risk reducing through a comparison of the texts, the scope of other provisions, which embody prohibitions, and which, while they contain no adverb, are nevertheless just as absolute in character. http://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.33_GC-IV-EN.pdf (accessed 24 June 2018). See Carducci, 2009.

-

[25]

The Hague Convention of 1907 (IV), Article 56.

-

[26]

This formulation has existed since The Hague Convention, 1899, Article 23 (g). See, for instance, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 8 (b) (xiii), https://www.icc-cpi.int/nr/rdonlyres/ea9aeff7-5752-4f84-be94-0a655eb30e16/0/rome_statute_english.pdf (accessed 24 June 2018).

-

[27]

Ibid., Article 8 (e) (xii). “Pillaging a town or place, even when taken by assault” is also defined as a war crime, Article 8 (e) (v). See also Carducci, 2009, Article D.

-

[28]

First Protocol, The Hague, 14 May 1954, http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13637&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed 20 October 2018).

-

[29]

Ibid., Respect for Cultural Property, Article 4 (3). Israel signed the convention on 14 May 1954. It has not been effective in Israel, nor in other armed conflicts as Kaye Lawrence points out. For instance, during the Iran-Iraq War many ancient monuments in Iran were deliberately destroyed, and during the Iraq-Kuwait conflict, the Kuwait Museum was practically stripped bare. Kaye Lawrence, “Looted Art: What Can and Should be Done,” Cardozo Law Review, December 1998, p. 665.

-

[30]

Nicholas Saunders, Trench Art: Materialities and Memories of War, Oxford, Berg, 2003; Margaret H. Higonnet, “Souvenirs of Death,” Journal of War and Culture Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2008, p. 65–78.

-

[31]

James J. Weingartner, “Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945,” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 61, no. 1, 1992, p. 53–67; Simon Harrison, “Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: Transgressive Objects of Remembrance,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 12, 2006, p. 817–836, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2006.00365.x (accessed 20 October 2018); and Wendy Kozol, “Battlefield Souvenirs and the Affective Politics of Recoil,” Photography & Culture, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, p. 21–36.

-

[32]

Harrison, 2008, p. 775, p. 778.

-

[33]

Higonnet, 2008, p. 67, 69.

-

[34]

Konstantin Akinsha, “Why Can’t Private Art ‘Trophies’ Go Home from the War?” International Journal of Cultural Property, vol. 17, no. 2, 2010, p. 257–290.

-

[35]

Kozol, 2012, p. 23.

-

[36]

Akinsha, 2010, p. 284.

-

[37]

John Dower, “Triumphal and Tragic Narratives of the War in Asia,” The Journal of American History, vol. 82, no. 3, 1995, p. 1124–1135; Weingartner, 1992; Kozol, 2012.

-

[38]

Harrison, 2008, p. 785.

-

[39]

Ibid.

-

[40]

Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 1993, p. 133–134.

-

[41]

Susan Pearce, On Collecting: An Investigation into Collecting in the European Tradition, London, Routledge, 1995, p. 236–244.

-

[42]

Stewart, 1993, p. 134.

-

[43]

The work of Palestinian and non-Jewish photographers is discussed in Sela, 2000; 2009; Sela Rona, [voir PDF pour traduction] 1948-1891 [Chalil Raad—Photographs 1891–1948], Tel-Aviv, Helena and Gutman Museum of Art, 2010; Yeshayahu Nir, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Early Photography in Eretz-Israel], [voir PDF pour traduction] [Early Photography in Eretz-Israel—], in Eli Schieler and Levin Menahem (eds.), Jerusalem, Ariel Publishers, 1989; Ellie Schiler, The First Photographs of the Land of Israel, Ariel, vol. 66–67, 1989; Ami Steinitz [voir PDF pour traduction] [Region of Distance], Studio Art Magazine, vol. 113, 2000, p. 45–59; Issam Nassar, “Familial Snapshot: Representing Palestine in the Work of the First Local Photographer,” History & Memory, vol. 18, no. 2, 2006, p. 139–155; Issam Nassar, [voir PDF pour traduction] 1850–1948 [Different Snapshots, Palestine in Early Photography], Beirut and Ramallah, Kutub and Qattan Foundation, 2005; Issam Nassar, “Early Local Photography in Palestine: The Legacy of Karimeh Abbud,” Jerusalem Quarterly, vol. 46, Summer 2011, p. 23–31; Vera Tamari, Palestine Before 1948, Not Just Memory, Khalil Raad (1854-1957), Ramallah, Institute for Palestine Studies, 2013; [voir PDF pour traduction] [Karimeh Abbud, Pioneer of Female Photography in Palestine], Beith Jala, Diyar, 2011.

-

[44]

Daoud Saboungi, who was a Christian, began photographing in Jaffa in 1892, see Yeshayahu Nir, [voir PDF pour traduction] [Jerusalem and Eretz-Israel: In the Footsteps of Early Photographers], Jerusalem, Israel Defense Forces Publishing House,1986, p. 99, 225. Eyal Onne claims that additional Arab photographers, for example, T.J. Alley or Putman Cady, began operating at the end of the nineteenth century; see Eyal Onne, Photographic Heritage of the Holy Land, 1839–1914, Institute of Advanced Studies, Manchester Polytechnic, UK, 1980, p. 14–15. However, Onne publishes very little information about their origin, nationality, and work. Another photographer active in Jaffa around 1912 was Sawabini.

-

[45]

Karimeh Abbud started to photograph in Jerusalem in 1914, but the bulk of her work is from the 1920s and 1930s. See the film Restored Pictures (Mahasen Nasser-Eldin, 2012).

-

[46]

As stated in an advertisement published in El-Carmel, 7 February 1924, p. 1.

-

[47]

Hanna Safieh started to photograph as a teenager in the mid-1920s. He developed his work during the 1930s. Ali Za’arur started working in the late 1920s, but his significant work was done in the 1940s (Sela, 2000, p. 174). Ibrahim Rissas started photography as a hobby, but later developed it as a profession (information from interviews with Rassas family in 2017).

-

[48]

Sela, 2000, p. 163–177. It is also important to emphasize the Armenian photographers such as Elia Kahvedijan in Jerusalem (from the 1920s) and Hrnat Nakashian in Jaffa (from 1943) who represented Palestinian issues. Other Palestinian photographers and photography studios were active in that period (and their histories still need to be researched), among them Studio Alhambra, Studio Roxy (Ramallah), Photo Boudir, Yusef Shamieh (Bethlehem), and in Jerusalem—Mohamad Said Al-Rissasi, Farah Auwi, Shukri Merrar, and Minass Julifian, to mention a few.

-

[49]

This conflict has its roots in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with the Jewish immigration to Palestine (since 1881), the birth of the Zionist nationalist movement, and the Palestinian nationalist movement. During the British mandate in Palestine (1917–1948), the Palestinians fought against the massive Jewish immigration and settlement in Palestine (mainly in 1920–1921, 1929, 1936–1939). The collision between those two forces eventually escalated in 1947‒1948 with, among others, the end of the British Mandate.

-

[50]

Sela, 2000, p. 175.

-

[51]

From the text of an advertisement in The Palestine Post, 14 December 1944, p. 3. In the article, his family name is written as “Al-Risasi.” Family members have verified that it is the same person. As far as it is known, this is the first organization established within the Palestinian photography community and it testifies of the central role that photography played in society and of photographers’ wish to produce influential work. In 1 January 1946 this initiation was expanded and fifty Arab photographers from “all over Palestine established their first professional association at a meeting at the Jerusalem Arab Chamber of Commerce” (“Fifty Arab Photographers,” The Palestine Post, 2 January 1946, p. 3).

-

[52]

Until World War I, Raad and Krikorian worked separately and had independent photography stores. See Fig. 5 for a photograph from the end of the nineteenth century, beginning of the twentieth century of the American Colony Photographers. Then, until approximately 1933, they joined forces and worked together.

-

[53]

Sela 2000, p. 174–175; 2009, p. 96–103, “Ali Za'arur,” 2018.

-

[54]

I saw his archive during my research.

-

[55]

Sela, 2009, Sela, “Ali Za’arur,” 2018. Za’arur was at the time in his late forties, part of Ibrahim Rissas’ generation, while Chalil Rissas was young and adventurous and willing to take risks.

-

[56]

Sela, 2000, p. 175. Translation from Hebrew by the author. [voir PDF pour traduction]

-

[57]

Translation from Hebrew by the author. [voir PDF pour traduction] Haganah Archive (for instance, image 6523).

-

[58]

Harrison, 2006; 2008; Higonnet, 2007; Akinsha, 2010, p. 257–290.

-

[59]

Interview with the looter’s son, Sela, 2009, p. 96–103.

-

[60]

“IDFA keeps Israeli military documentation of all sorts, including files, publications, audio and video, photographs, maps and posters. IDFA and its subsidiaries also house documentation of Jewish military organizations that were active before the establishment of the State of Israel.” See IDFA’s website at: http://www.archives.mod.gov.il/Eng/Pages/geninformation.aspx (accessed 3 August 2018).

-

[61]

“The records in the IDFA are produced by the Defense Establishment, and therefore according to the Archive Law are classified for fifty years from the day of their creation”; see IDF & Defense Establishment Archives, Ministry of Defense, The IDF and Defense Establishment Archives, Rules, Orders and Instructions, http://www.archives.mod.gov.il/sites/English/About/Pages/The_IDF_and_Security_Establishment_archive.aspx (accessed 16 April 2019). Some materials are censored for seventy years: Ravid, Barak, 2010. “State Archives to Stay Classified for 20 More Years, PM Instructs”, Haaretz, July 28: https://www.haaretz.com/1.5152655 (accessed 20 February 2019). According to the Freedom of Information Act, 1998 and the Archive Law, 1955, section 10, the IDFA has the power to define materials as a threat to Israel’s national security or foreign relations and classify them as secret and restricted for an unlimited period dependent on IDFA’s sole decision.

-

[62]

IDFA, file 553/54/154.

-

[63]

[voir PDF pour traduction] Bamahane, vol. 60, no. 40, 2 June 1949, p. 19; and “Pictures and the Hidden through Arab Lenses (Imprisoned Photographs),” Ibid., Bamahane, vol. 61, no. 41, 9 June 1949, p. 18. Translated from Hebrew by the author.

-

[64]

Higonnet 2008, p. 67.

-

[65]

Bamahane, vol. 61, no. 41, 9 June 1949. Translated from Hebrew by the author:

[voir PDF pour traduction]

-

[66]

See also Sela, “Israel's Art Scene Is Whitewashing the Nakba,” 2018.

-

[67]

Higonnet, 2008, p. 69.

-

[68]

[voir PDF pour traduction] [The Road to Independence, the Jerusalem War, Photographs from the Arab Side], Bamahane, vol. 161, no. 37, 10 May 1951, p. 12-13. Translated from Hebrew by the author.

-

[69]

Ibid, p. 12. Translated from Hebrew by the author:

[voir PDF pour traduction]

-

[70]

( IDFA 553/54, File 154):

[voir PDF pour traduction]

-

[71]

[voir PDF pour traduction]. Translated from Hebrew by the author.

-

[72]

An interview with Moshe Rashkes, 3 March 2008. Translated from Hebrew by the author.

[voir PDF pour traduction]

About the pillage by Rashkes, see also: Rona, Sela, "The Archive of Horror," IBRAAZ 006, 6 November 2013, http://www.ibraaz.org/platforms/6/responses/141 (accessed 31 July 2018).

-

[73]

Translated from Hebrew by the author. Moshe Rashkes, Days of Lead, Tel Aviv, Ma’arachot,” Israel Ministry of Defense, 1962, p. 105–107. See also Sela, 2009; 2018, Sela, “The Archive of Horror”.

[voir PDF pour traduction]

-

[74]

From my interview with Moshe Rashkes, see footnote 72. Translated from Hebrew by the author:

[voir PDF pour traduction]

-

[75]

Kozol, 2012, p. 33; Sela, “The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure,” 2018, p. 219–224.

-

[76]

Harrison, 2006, p. 818–819.

-

[77]

Ibid., p. 831–832; see also Higonnet, 2008, p. 67.

List of figures

Fig. 1

Fig. 2‒3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Jerusalem (El-Kouds). The Jaffa Road, main thoroughfare of the new city, c. 1898–1914. Raad and Savvides’ studios are visible on the right side of the road and Krikorian’s studio on the left.

Fig. 6

The text accompanying the image reads: “Arab Gang—parade, 1947–1948.” The Palestinian flag is visible on the right. As catalogued in the archive, the photograph (a part of a larger group of images) has been “accepted since the 1967 mopping-up operation.—November 2002—there is an opinion by the attorney general to allow the use of seized materials.”

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

The text accompanying the image reads: “The Commercial Center in Jerusalem, 1947–1948.” “The photograph was found [among the belongings of] an Arab prisoner. Received from Rashkes Moshe.” Rashkes, however, contradicts this version by asserting that the photograph was taken from the dead body of an Arab soldier.