Abstracts

Abstract

There is growing recognition in Canada around the role of intergenerational trauma in shaping physical and mental health inequities among Aboriginal[1] youth. We examined recommendations on best practices for addressing intergenerational trauma in interventions for Aboriginal youth. Academic-community partnerships were formed to guide this scoping literature review. Peer-reviewed academic literature and “grey” sources were searched. Of 3,135 citations uncovered from databases, 16 documents met inclusion criteria. The search gathered articles and reports published in English from 2001-2011, documenting interventions for Indigenous youth (ages 12-29 years) in Canada, the United States, New Zealand and Australia. The literature was sorted and mapped, and stakeholder input was sought through consultation with community organizations in the Calgary, Canada area. Recommendations in the literature include the need to: integrate Aboriginal worldviews into interventions; strengthen cultural identity as a healing tool and a tool against stigma; build autonomous and self-determining Aboriginal healing organizations; and, integrate interventions into mainstream health services, with education of mainstream professionals about intergenerational trauma and issues in Aboriginal health and well-being. We identified a paucity of reports on interventions and a need to improve evaluation techniques useful to all stakeholders (including organizations, funders, and program participants). Most interventions targeted individual-level factors (e.g., coping skills), rather than systemic factors (e.g., stressors in the social environment). By addressing upstream drivers of Aboriginal health, interventions that incorporate an understanding of intergenerational trauma are more likely to be effective in fostering resilience, in promoting healing, and in primary prevention. Minimal published research on evidence-based practices exists, though we noted some promising practices.

Keywords:

- Aboriginal,

- Indigenous,

- youth,

- intergenerational trauma,

- historical trauma,

- interventions,

- best practices,

- health

Article body

Introduction

For Indigenous communities around the world, colonialism has created negative health outcomes that resonate across generations (Sotero, 2006). In Canada, the Indian Residential School policy stands out as particularly harmful. With it, children of First Nations, Métis and Inuit descent were forcefully taken from their families at a young age and sent to boarding schools for the purposes of cultural and linguistic assimilation (AHF 2006a-c). As documented in the final report released by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015), the cultural and linguistic loss accompanied widespread physical, sexual and psychological abuse of students (Smith et al., 2005). Many residential school survivors have displayed a host of mental and physical health issues (Quinn, 2007; Bombay et al., 2014). A phenomenon called “intergenerational trauma” (also known as historical trauma transmission, collective trauma, transgenerational grief, and historic grief) has occurred among families of survivors, including among those who did not themselves attend the schools (Quinn, 2007; Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998). Intergenerational trauma is defined by Evans-Campbell (2008, p. 320):

A collective complex trauma inflicted on a group of people who share a specific group identity or affiliation…. It is the legacy of numerous traumatic events a community experiences over generations and encompasses the psychological and social responses to such events.

Evidence links many negative health outcomes to intergenerational trauma. One systematic review of research in Canada highlighted the link between colonization, cultural discontinuity, and mental health and violence (Kirmayer et al., 2000). The association between intergenerational trauma and substance abuse has been found in relatives of trauma survivors who develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Brave Heart, 2003). Other studies have identified connections between intergenerational trauma and homelessness among Aboriginal men (Menzies, 2006), as well as youth suicide (Strickland, et al., 2006). Hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS in youth have also been linked to historical trauma and prior experiences of sexual abuse (Pearce et al., 2008; Craib et al., 2009). Such research highlights a need to explicitly address intergenerational trauma at individual and population levels, for the development of effective interventions and prevention efforts (Roy, 2014a).

Discussions about Aboriginal youth are often framed in terms of disproportionately negative indicators of health status and well-being. One study found significantly lower measures for the United Nations Human Development Index, mortality rate, educational attainment and household income in Aboriginal youth relative to other Canadians of the same age (15-29 years) (Guimond & Cooke, 2008). Aboriginal youth suicide rates are much higher than national averages (Chouinard et al., 2010); relative to non-Aboriginal youth, First Nations youth commit suicide about six times as often, and Inuit youth about eleven times as often (Health Canada, 2011). HIV and diabetes mellitus rates are also significantly higher (Health Canada, 2009). Public attitudes towards Aboriginal youth are often constructed on prevailing stereotypes and colonial attitudes, which remove youth from the broader historical context of colonial practices and subjugation that have contributed to these contemporary negative health outcomes (Hodge et al., 2009).

Other intersecting factors contributing to health issues are complex, raising questions when designing interventions: Is it best to address the source or outcome of trauma? How can interventions halt the negative consequences of intergenerational trauma? What is the role of older generations in youth interventions? Can interventions to address cultural loss and alienation be integrated into mainstream interventions tested among non-Aboriginal populations? To address these, we sought information on successful interventions by undertaking a scoping literature review to identify meaningful practices for addressing intergenerational trauma with Aboriginal youth. The seminal work of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) guided the analysis (AHF, 2006a-c). Our objectives were to identify: 1) how intergenerational trauma among Aboriginal youth has been addressed in interventions, and corresponding promising and/or best practices; 2) whether and how interventions reflect components of the AHF healing framework; and 3) what specific health or social outcomes were addressed, and the means of evaluation. This paper begins with an overview of the AHF framework and guiding definitions, followed by presentation of the methods and the results, and a discussion of future directions.

A framework linking trauma and healing

Founded in 1998 and in operation until 2014, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) aimed to address healing among individuals, families and communities affected by the residential school system and its intergenerational legacy. Until 2006, it worked with multiple stakeholders from across Canada, creating evidence-based background materials and frameworks. It funded a large number of healing projects, and in 2006 released a three-volume final report on funded work (AHF, 2006a-c). The term ‘healing’ is defined in AHF reports according to a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples framework (2006c, p. 7):

Healing, in Aboriginal terms refers to personal and societal recovery from the lasting effects of oppression and systemic racism experienced over generations. Many Aboriginal people are suffering not simply from specific diseases and social problems, but also from a depression of spirit resulting from 200 or more years of damage to their cultures, languages, identities and self-respect.

The AHF report notes difficulties with the concept of ‘best practices’ around Aboriginal healing, as ‘best practice’ is primarily a Western concept emphasizing replicability and an empirical evidence base. Instead, the AHF uses promising healing practices, defined as (2006c, p. 7): “Models, approaches, techniques and initiatives that are based on Aboriginal experiences; that feel right to Survivors and their families; and that result in positive changes in people’s lives.” While embracing AHF’s use of the term ‘promising practice’, the terms ‘best practice’ and ‘evidence-based practice’ are also used in this paper, in reflection of their common usage in the broader body of published intervention and evaluation literature.

Conceptual models for intergenerational trauma seek to explain the pathways by which trauma is transferred across generations. The AHF recommends the integration of such a model into the rationale, design and implementation of interventions. Intergenerational trauma theory offers context for the AHF framework (Sotero, 2006; Brave Heart, 2003; Wesley-Esquimaux & Smolewski, 2004; Whitbeck et al., 2004). According to the theory, trauma begins with collective subjugation, loss, abuse or other forms of population-level oppression and is not limited to those who directly experience it. Instead, cumulative effects of trauma are passed down along generations and result in maladaptive coping (e.g., substance abuse, violence, suicide), often amplified when youth are traumatized by their caregivers. Contemporary structural and systemic inequities, such as personal-level and institutional-level racism, are further sources of oppression and cultural alienation, aggravating intergenerational trauma by reinforcing ancestral stories of oppression.

The AHF framework identifies three necessary elements for healing interventions (2006c, p. 15): integration of an Aboriginal worldview throughout the planning, design and implementation of an intervention; a culturally safe healing environment; and healers who are competent to heal. The AHF cites values of “wholeness, balance, harmony, relationship, connection to the land and environment, and a view of healing as a process and lifelong journey” (ibid) as consistent with Aboriginal worldviews, and thus integral to effective healing programs. Cultural and personal safety refers to environments in which participants can feel physically and emotionally welcomed. Finally, the capacity of a program to heal rests in the ability of healers to establish cultural and personal safety.

The AHF (2006c) identifies three complementary intervention pillars; a holistic program incorporates all three for best results. The first pillar is “reclaiming history”, or “legacy education”, which seeks to raise awareness of residential school (or other traumatic) experiences and consequences. In so doing, it builds an understanding of shared experiences; allows responses to trauma to be seen as a result of institutional forces; and allows children to better understand the situation of their parents. By facilitating understanding, this pillar can motivate survivors and youth to pursue healing (AHF, 2006c). The second pillar is “cultural interventions”, drawing on cultural teachings including healing ceremonies, pow-wows, language programs, and traditional journeys that reinforce a positive sense of identity (AHF, 2006c). The third pillar is “therapeutic healing”, which can include traditional therapies, Western-based therapies, or other non-Aboriginal therapies, alone or in combination with each other. Western approaches generally favour medical models of disease that look at individual-level pathology and act to alleviate suffering. Rooted in Aboriginal worldviews, traditional Aboriginal therapies are generally more holistic and keep the individual integrated within a collective. Combined therapies attempt to integrate two or more approaches by embedding traditional components into mainstream or alternative medical therapies, or by using Western or other non-Aboriginal models within a traditional Aboriginal setting (AHF, 2006c).

The AHF stresses that evaluations of the effectiveness of interventions should be of value to all stakeholders including researchers, organizations, governments, families, and program participants (2006b). AHF-identified questions of value to decision-makers include: “What were the best or promising practices and greatest challenges? What lessons have been learned? What can be done to better manage program enhancement? Did we address the need? [And], is the healing process sustainable?” (2006b, p. 8).

Although guided principally by the AHF framework for healing, the approach in this article is also consistent with the Touchstones of Hope framework. Notably, there is support of the phases of reconciliation through respectful relationships in the design, implementation, and monitoring of youth-centered healing programs, and in learning from restorative efforts to heal from harm (Blackstock et al., 2006, p. 8-9). As reflected in the results and conclusions, findings of this review also highlight the Touchstones of Hope through evidence around the promotion of self-determination and the role of non-Aboriginal professionals in decision-making that affects youth (Ibid, p. 10).

Methods

A scoping review is a systematic method for reviewing literature, to summarize and examine its current state and to identify gaps (Brien, et al., 2010; Kania et al., 2013). We drew on the methodological framework of Arksey and O'Malley (2005) to: identify the research question and relevant studies for analysis; chart data; collate, summarize and report results; and, consult stakeholders. The following question guided our research: What recommendations exist for promising and/or best healing practices for interventions that address intergenerational trauma among Aboriginal youth in Canada?

The inclusion criteria sought documents describing interventions for Aboriginal youth ages 12-29 years in Canada, the United States, Australia or New Zealand. These four countries have similar colonial histories, and international collaborations in research and advocacy concerning Aboriginal populations (INIHKD, 2010). Sources also addressed intergenerational trauma in a broad sense; for example, addressing ongoing abuse or oppression while linking to colonialism. We included documents published in English from 2001 to 2011 from peer-reviewed and grey literatures. We excluded literature documenting interventions with youth as part of a mixed-age population; interventions for youth of multiple ethnic groups; and interventions targeting non-Aboriginal youth who may be experiencing intergenerational trauma.

We searched the following academic databases: MEDLINE/PubMED, EMBASE, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL, CBCA, Social Work Abstracts, Canadian Periodical Index, Social Services Abstracts, Family and Society Studies Worldwide and Family Studies Abstracts. We also searched the Canadian Health Research Collection and Canadian Research Index for “grey” literature, which refers to publications (from government sources, academic institutions, businesses, non-profit agencies and other organizations) which are not produced by a commercial publisher (Public Health Action Support Team, 2011). We scanned references of selected papers in order to identify additional relevant interventions meeting inclusion criteria, and conducted internet searches on youth programs mentioned in Volume III of the AHF report Promising Healing Practices. An initial title-abstract screen of all identified citations helped exclude unrelated documents, with those eligible for inclusion going on to full-paper screening.

We sorted and mapped the selected interventions according to the sex of participants, intervention location, health issue addressed, type of intervention in terms of AHF pillars framework, adherence to the three elements in the AHF framework for healing, evaluation techniques, and proposed recommendations. We then conducted stakeholder consultation by presenting results at a community gathering in December 2011 in Calgary, Alberta. The gathering was attended by approximately 70 community members and representatives from 60 area agencies, many serving Aboriginal youth. Following presentation of results, attendees broke into small groups for roundtable discussions around three questions:

Of the recommendations that were discussed today, do you have similar practices in your agency’s programs?

How do you know what you do is effective in addressing intergenerational trauma?

What would your agency need to better implement and evaluate youth programming?

Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed, while notes were taken throughout. Common ideas and emerging themes were coded.

Results

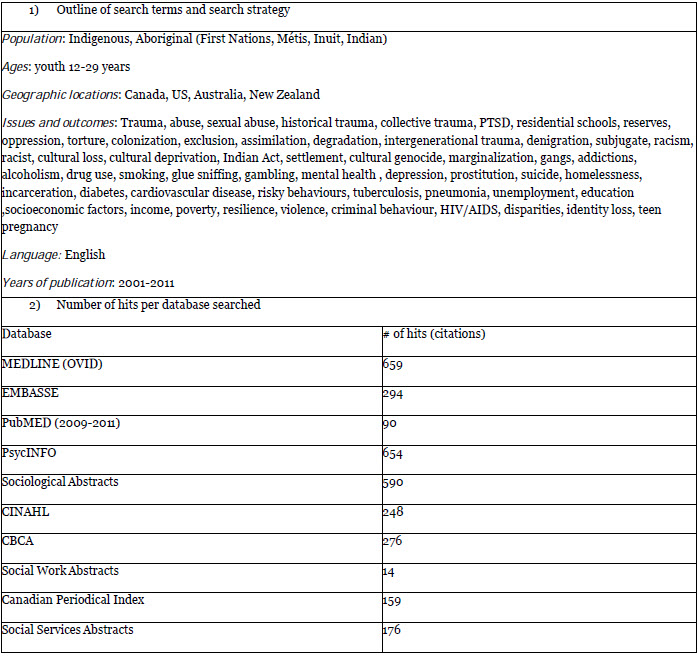

The database search yielded 3,135 unique articles (see Table 1), while the title and abstract screen determined 129 relevant and 153 possibly relevant. Seven additional papers were identified from screening reference lists of selected articles and the AHF report. After applying the inclusion criteria, 16 documents remained for the final review (identified in the References list with asterisks). Table 2 summarizes included documents.

Table 1

Search terms and database hits

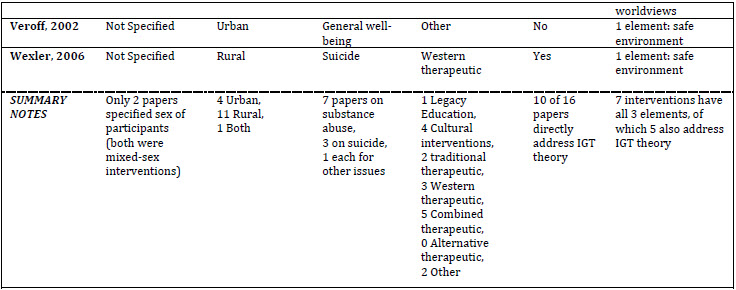

Table 2

Summary of characteristics of 16 papers reviewed

Intervention types

One intervention was aimed at reclaiming history, four were cultural interventions, two contained traditional therapeutic interventions, three were Western therapeutic interventions, five were combined therapeutic interventions, and two were labelled “Other” due to not fitting into AHF categories. One cultural intervention was also categorized as a traditional therapeutic intervention because of a mixture of components. Cultural interventions generally involved traditional excursions, community or large-scale gatherings, or programs immersing youth in traditional diets or special ceremonies. A cultural intervention from Ontario encouraged youth to learn how to prepare foods traditionally and distribute food in their community (Shantz, 2010). Another intervention in Western Australia focused on the intergenerational exchange of cultural traditions and positive coping skills, instead of focusing on the negative transfer of trauma (Palmer et al., 2006).

Most therapeutic interventions combined traditional and Western approaches. One sought to address alcohol use, modifying a program used in schools specifically for Cherokee youth. This was done by changing the existing 10-step program into a talking-circle and weaving into sessions the concept of self-reliance, which is important to the Cherokee community (Lowe, 2006). Another combined therapeutic intervention modified the Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools model (Jaycox, 2004) for use in an American Indian community, by reframing sessions around topics of historical injustice, traditional history, and coping through community. Though rooted in Western healing, the authors aimed to address PTSD from an American Indian perspective (Goodkind et al., 2010). One intervention undertaken with Inuit youth took the form of an art project, in which participants were encouraged to explore their identity (Veroff, 2002). Yet another intervention, this time aimed at young offenders, used alternative means of retribution to discourage risky behaviour (Lafreniere et al., 2005).

Addressing issues of health and well-being

Nearly half the documents (7 of 16) addressed alcohol or substance abuse. Other issues addressed included suicide, PTSD, depression, sexual abuse, HIV/AIDS, diet and diabetes, offender rehabilitation, and general well-being.

Urban or rural location

Of the 16 interventions reviewed, four took place in urban areas, working with youth not immersed within a larger Aboriginal community. Eleven described rural interventions, referring to areas within which a distinct Aboriginal community resided, or a town or village with a small population but a significant number of Aboriginal families (AHF, 2006c). One intervention, which featured an annual camp and used traditional activities to build resiliency, involving Aboriginal youth from both urban and rural settings (Skye, 2002).

Use of AHF framework

Determining coherence with the AHF framework first involved identifying whether intergenerational trauma theory articulated the rationale for intervention design, and, secondly, if it incorporated any of the three necessary AHF elements (i.e., guided by Aboriginal worldview; cultural safety; skilled healers). Ten of the 16 (63%) directly addressed intergenerational trauma theory, for instance articulating how intergenerational trauma affects health outcomes, how trauma is transmitted across generations, or how it may come about. Although the other six papers did not directly address intergenerational trauma theory, they had some element addressing cultural deprivation, historical circumstances, colonization, or oppression. Most included only one of the three necessary elements for healing interventions listed by the AHF.

Evaluation techniques reported in papers

The literature documented varied evaluation techniques for assessing intervention effectiveness. Some papers reported the use of formal standardized measurement instruments, while others reported no evaluation mechanism. Only two offered detailed program evaluations, featuring quantitative scales (e.g., for depressive symptoms, PTSD, stress and coping) and follow-up assessments for long-term impact (Lowe, 2006; Goodkind, 2010). These detailed evaluations were conducted on combined therapeutic interventions that showed positive results immediately after the intervention, namely reduced stress and trauma; however, these reductions were not maintained after extended follow-up. In both cases, this reversal was attributed to interventions not altering the traumatic and/or stressful environments in which youth participants lived. Of papers reporting Western therapeutic interventions, two used quantitative assessments: one reported on the collective responses of Elders (Gilder et al., 2010); the other used “client complexity measures” that assessed changes in factors such as mental health or propensity for conflict (Holland et al., 2004). The final paper concerning a Western therapeutic intervention used specific interview questions to describe intervention outcomes (Wexler, 2006). For the two traditional therapeutic interventions, one used self-reported data on substance use and on perception of change in various psychosocial indicators, to quantitatively describe success (Aguilera & Plasencia, 2005), and the other used qualitative stories to support conclusions (Dell, et al., 2011). Only one paper (Aho & Liu, 2010) documented an intervention that could be categorized as “reclaiming history”; it lacked an evaluation.

Proposed recommendations

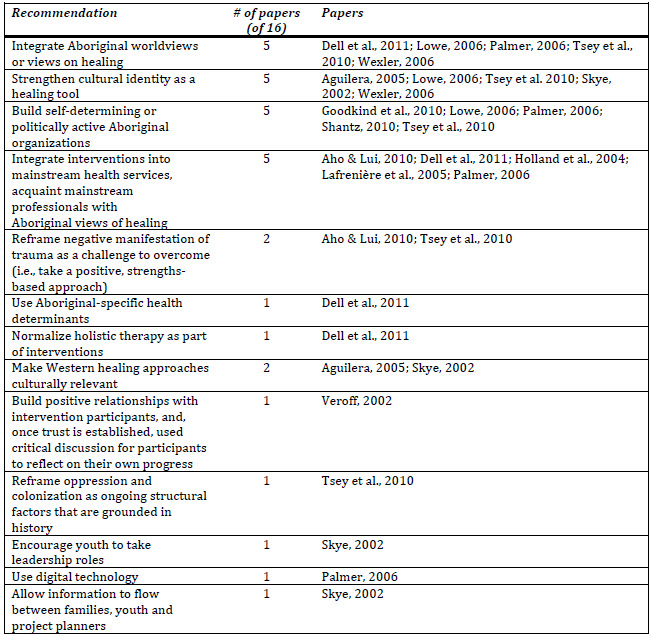

Table 3 summarizes the main recommendations drawn from the literature. Only two papers (Marlatt, et al., 2003; Higgins, 2005) offered no recommendations.

Table 3

Summary of recommendations made in papers

Many papers recommended approaches grounded in Aboriginal worldviews; empowering the cultural identity of youth; promoting autonomy of Aboriginal organizations; supporting political advocacy; and integrating effective interventions into existing health services. These are consistent with the AHF’s recommendations. Calls to integrate Aboriginal traditions and worldviews into interventions emphasized concepts of holism and interconnectedness to community and family. Recommendations concerning cultural identity of youth were based on the argument that a strong sense of identity can be a positive way to reduce stigma around some issues, as well as serve as a tool for building self-reliance and encouraging political and community engagement (Wexler, 2006).

Papers also advocated for increased autonomy of Aboriginal organizations and youth groups, and the capacity for these groups to be politically active. Two articles (Shantz, 2010; Goodkind, et al. 2010) identified the need for youth groups to be agents of political advocacy, as a means to build resiliency and empower youth to combat ongoing oppression. The literature also emphasized self-determination for Aboriginal groups, in order for them to avoid being constrained by organizational structures with which they are uncomfortable, and to be fully in charge of their own programs, rather than being directed by other agencies or governments. Additional recommendations addressed the need for Aboriginal interventions to better tie into existing services. Mainstream health agencies and workers were called to learn more about Aboriginal worldviews and determinants of health, and apply this knowledge for the creation of culturally competent and culturally safe care. Broadly, the literature recommended that health departments work with Aboriginal healers and with each other, to yield interventions culturally rooted in Aboriginal ideas of healing. Recommendations specifically geared towards addressing intergenerational trauma were few, but included the need to ground discussions of oppression and discrimination in a historical context, and to explain how ongoing oppressive forces link with disparities along health outcomes and the social determinants of health.

Stakeholder consultation

According to stakeholder consultation participants at the community gathering, there is a move to integrate Aboriginal worldviews into programming at various agencies in the Calgary area. Stakeholder consultation participants articulated general consensus on the need for holistic intervention. Various agencies reported offering cultural programming, and explicitly connected the integration of culture to the goal of building a strong sense of identity in youth. In concordance with the AHF’s element around the requirement for skilled healers, various agencies reported efforts to ensure staff competency around Aboriginal youth well-being. Participants also indicated that Aboriginal staff may provide more comfortable healing environments. Finally, participants reflected that more could be done by their agencies to explicitly address intergenerational trauma as an issue.

Some participants disclosed that programs do not always assess for intergenerational trauma, although health and well-being issues related to intergenerational trauma are often addressed. Some agencies described using questionnaires to assess the effectiveness of programs. Pre- and post-intervention assessments were occasionally used, some with standardized instruments; in other cases, more informal surveys were employed. Other reported indicators for program success included oral feedback (e.g., direct interviews, informal discussions). Some participants argued that subjective, verbal assessment from a youth participant may be the best marker of impact, reflecting that verbal feedback is in line with oral traditions among Aboriginal cultures. Levels of attendance and participation were also deemed by some participants to be key indicators of program success.

Participants expressed considerable frustration around funding barriers during stakeholder discussions, including: limited access to funding opportunities; a lack of continued funding for successful programs; inconsistent funding impacting sustainability and continuity of programs; funding allocation criteria not reflective of individual and community needs; and lack of accurate understanding among funders around key issues to address. Some argued that, relative to mainstream programming, Aboriginal youth programming requires more financial resources to properly execute and evaluate, due to the enhanced complexity of the issues at hand. Participants felt that greater collaboration between stakeholders could facilitate sharing of ideas and promising practices, yielding new funding avenues, while collaboration with researchers and/or universities could improve evaluation capacity.

Participants identified involvement of families in youth programming as helpful for parental buy-in and quality-improvement feedback. Participants considered increased access to skilled Aboriginal staff for programs and services critical for intervention effectiveness, as they felt that healers who were Aboriginal themselves could provide a more comfortable setting by more readily empathizing with youth experiences. Finally, participants desired better education and training among staff at agencies about the concept of intergenerational trauma.

Discussion

The development of interventions to address intergenerational trauma among Aboriginal youth appears to be in its infancy. More comprehensive, evidence-based interventions are required. Among interventions captured in this review, most were not formally evaluated, adding reporting and evaluation challenges to the task of identifying promising healing practices. This gap may prove a barrier to overcoming key concerns identified by stakeholders around generating funding support for innovative programming, as standards among policy makers and funders may be more demanding than that outlined by the AHF. None of the interventions encapsulated all three pillars recommended by the AHF. It may not always be practical for a single program to contain all three; accordingly, a multipronged approach is warranted, involving coordination and collaboration across organizations and sectors. Further research could examine whether interventions can be successful without all three pillars. It is important to note that the success of interventions is highly influenced by the environment in which youth find themselves; if the environments are highly traumatic and not supportive of healing, skills developed during an intervention are less likely to be maintained. This is a basic tenet of health promotion (WHO, 1986), and was reflected in two interventions (Lowe, 2006; Goodkind, et al., 2010). Thus, interventions are required that target changes within the community as a whole, and support youth to become agents of change within their environments.

The sole legacy education intervention identified was part of a new youth suicide prevention strategy among Maori communities in New Zealand. The intervention sought to situate high levels of suicide within a colonial and historical context to reframe existing strategies that target individual pathology (Aho & Liu, 2010). Legacy education, focused on increasing awareness of colonialism and its ongoing impacts, may be vital for youth. Despite not directly experiencing historical events such as residential schools, youth are nonetheless deeply affected by the intergenerational impacts on their families and communities (Wesley-Esquimaux & Smolewski, 2004), and often feel personally responsible for their suffering. Cultural interventions such as the Midwinter Harvest Food Program (Shantz, 2010) and the Yiriman Project (Palmer et al., 2006) sought to train youth in traditional skills, while fostering personal connection with culture. Combined therapeutic interventions were the most common types identified, though both Western and traditional therapeutic practices were also promising.

One challenge in evaluation for effectiveness may be in balancing Western techniques and Aboriginal worldviews in seeking indicators of success appropriate for communities (Robinson & Tyler, 2006). The National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) suggests that this challenge is not an excuse for avoiding the search for excellence, as Aboriginal youth equally deserve effective, evidence-based interventions, if not more so when viewed through an equity lens. As concepts such as resilience, engagement with cultural identity, cognitive reframing of challenges, and internalized trauma become articulated, ways to measure them need development. The sources in the review that included some form of evaluation did little to address the question of balance between Western and Aboriginal views on evaluation. They generally chose either Western or Aboriginal-centric methods, rather than finding a hybrid that addressed advantages and disadvantages of each through an approach of “two-eyed seeing” (Martin, 2012). Evidence on efficacy and effectiveness should be gathered, so that funds are not used on less successful programs, resulting in opportunity costs; that is, the use of funds on ineffective programs.

Funding agencies often expect quantitative approaches to evaluation in order to assess effectiveness of outcomes. However, oral or narrative methods may be more culturally appropriate, pointing to the importance of qualitative methods such as interviews, oral accounts and narratives. Qualitative methods allow a high degree of insight into mechanisms through which interventions function. Meanwhile, well-constructed quantitative instruments – properly validated for the context or population at hand – typically allow more generalizable assessment of group-level outcomes. The outcomes of successful healing may include issues deemed important by communities. Mixed-methods and multiple-methods research involves combining qualitative and quantitative methods (Sandelowski, 2000; Morse & Niehaus, 2009). In one scoping review concerning evaluation of health promotion interventions, authors found that evaluations using both quantitative and qualitative methods better capture the complex processes at play in interventions (Kania et al., 2013). Thus, a mixed- or multiple-methods approach to evaluation, done in a way that engages Aboriginal worldviews and reflects community perspectives and priorities, may resolve the evaluation dilemma (Roy, 2014b).

While colonization and oppression were addressed in most documents, not many interventions incorporated intergenerational trauma theory. The same conclusion emerged at the stakeholder consultation gathering, regarding descriptions offered by participants of their own agencies’ programs. The lack of concrete incorporation of intergenerational trauma theory into intervention design may yield programs that miss the broader, upstream context linking Aboriginal youth well-being to past atrocities. Further research is warranted on how to practically apply existing frameworks for healing to intervention design. Sotero (2006) explains that for public health to effectively address intergenerational trauma, it is important for practitioners to understand the place of the individual in Aboriginal perspectives. This means situating the individual in relation to community, the land, the family and history. Therefore, simply adding in some cultural elements to a pre-existing program can be ineffective – even tokenistic – without broader engagement with Aboriginal worldviews. The need for personally and culturally safe environments was reflected with 14 of 16 documents referencing efforts to make participants feel comfortable and safe. Cultural safety in health settings is defined by NAHO (2008) as an environment where professionals “can communicate competently with a patient in that patient’s social, political, linguistic, economic, and spiritual realm” (p. 7). Other definitions suggest it involves reflection on the part of health professionals on questions of power and privilege, ensuring that clients can feel empowered in interactions with health professionals (ANAC, 2009). NAHO indicates that the setting in which healing takes place must not diminish a person's confidence or alienate them from cultural affiliations or identity (NAHO, 2008). Some of the interventions reviewed took place in community centres, or in parks or outdoor settings; these may be inherently less threatening for participants. None of the interventions reviewed took place in a hospital or clinical setting; this may indicate that hospitals or clinical settings are not seen as ideal locations for healing from intergenerational trauma; or, alternatively, that the clinical health sector is not directly working to address intergenerational trauma among patients. Some of the interventions reviewed took place in schools; schools may or may not be a ‘safe’ environment for Aboriginal youth – a question that was not deeply examined in the papers. As hospitals, clinics and schools are often practical locations for public health interventions (due to ready access to target populations), there is a need to consider how cultural and personal safety can be increased in these locations.

The final element in the AHF framework, the capacity of healers, was not explicitly addressed in many of the documents. The importance of having committed and well-trained practitioners, staff, and volunteers, is vital to best practice (Mable & Marriott, 2001). Aboriginal nurses have been identified as holding a unique position in healing intergenerational trauma (Lowe, 2002; Struthers & Lowe, 2003). However, before identifying one profession or group to shoulder the task of healing, it is important to assess their capacity and to foster capacity-building across all sectors, while also supporting the healers’ own level of healing from past trauma.

As discussed above, a recommendation emerging from the review was to better tie interventions into existing mainstream health systems, and to assist mainstream practitioners to become versed in Aboriginal ways of healing. This seems contradictory to another recommendation that emerged, concerning the need for self-determination and autonomy in organizations governed by Aboriginal peoples. While the latter is undoubtedly important, limiting healing work to exclusively Aboriginal organizations may reduce the range and accessibility of interventions available, and place an undue service burden on organizations that may already be struggling to meet their service mandates. For instance, a study of services for urban Aboriginal peoples facing homelessness found few Aboriginal-specific services, despite disproportionate representation among the homeless population (Thurston et al., 2013). Integration of Aboriginal-specific services with, or drawing support from, existing mainstream services carries potential benefits, including support in rural areas; access to existing health infrastructure; improved accessibility to specialists; greater funding opportunities; and improved capacity for evaluation (DeGagne, 2007). Partnership and community engagement may be mediating forces in allowing effective Aboriginal-specific programming to be offered within mainstream services, in a manner that accounts for the concurrent need for independence and self-determination. Carefully crafted terms of partnership may facilitate finding the right balance in this regard. Growing interest in collaborative research and practice exists in public health; while it is often challenging to execute, the benefits occur at many levels and accrue over time (Israel et al., 1998; Roy et al., 2014). Meaningful engagement of Aboriginal communities in research should not be neglected, and should be of value to all parties involved in the research (Dunne, 2000). The community and service-provider consultation for this scoping review facilitated networking between community groups and academic researchers, nurturing the possibility for fruitful and equitable relationships to further research and practice with Aboriginal youth (Crooks, et al., 2009).

A lack of attention to gender in trauma and healing was clear. Many documents did not differentiate intervention participants by sex, and none discussed the needs of males, females, transgender, or gay and lesbian or two-spirited people. The experience of intergenerational trauma and potential for ongoing abuse may differ according to gender, as may health-based manifestations of trauma; thus, this gap is notable. The role of setting was also ignored, specifically around designing interventions for urban or rural populations. The importance of the above was illustrated in a study of differences in suicidal thoughts and attempted suicide among American Indian youth. This study found lower rates of psychosocial problems related to suicide ideation among urban youth, even though rates of attempt in both rural and urban populations were similar (Freedenthal & Stiffman, 2004). Finally, few interventions attempted to influence policy or address ongoing structural factors that cause systemic oppression and allow intergenerational trauma to persist.

Conclusion

According to the Canadian Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, the framing of issues facing Aboriginal youth must “move beyond the near exclusive focus on problems and begin to explore a more constructive approach, one emphasizing the contribution Aboriginal youth now make, and can continue to make, to Canada's future” (p. 4) (Chalifoux, 2003). In Canada, the residential school experience and other ongoing legacies of colonization continue to negatively impact Aboriginal youth. Interventions capable of effectively addressing intergenerational trauma are crucial to preserving and improving the health and well-being of Aboriginal youth, families and communities. As discussed here, a paucity of published research on best practices exists, in addition to significant oversights. Nevertheless, a number of promising practices are developing, and require rigorous and meaningful evaluation for support. Further research and action, across sectors in health, social services, and academia, are necessary to address the gaps identified in this review and improve capacity to address this critical issue.

Appendices

Appendix

List of abbreviations

AHF = Aboriginal Healing Foundation; HIV/AIDS = Human Immunodeficiency Virus / Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome; NAHO = National Aboriginal Health Organization; PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Acknowledgements

This research stemmed from an academic-community partnership between the University of Calgary, YMCA Calgary, and the Urban Society for Aboriginal Youth (USAY). It was funded by the City of Calgary Family and Child Support Services (FCSS). The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the other research team members: LeeAnne Ireland (USAY), Sharon Goulet (FCSS), Tanis Cochrane (YMCA), Christy Daniels (YMCA), Laurie Beatt (YMCA), David Turner, and Christy Morgan. We also thank Diane Lorenzetti (Research Librarian, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary) for her guidance with the database searches. We are grateful for the participation of attendees at the project’s community stakeholder gathering, who shared critical insight during the roundtable discussions. Finally, we also thank the four student volunteers who assisted with note-taking at that event: Keri Williams, Laura Clark, Carlen Ng and Jordana Bain.

Note

-

[1]

While recognizing the move towards the preferential use of the term “Indigenous”, we have used “Aboriginal” in this paper because it remains, at this time, the most commonly accepted umbrella term for the Indigenous peoples of Canada.

Bibliography

- *Aguilera, S., & Plasencia, A.V. (2005). Culturally appropriate HIV/AIDS and substance abuse prevention programs for urban Native youth. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 37(3): 299-304.

- AHF—Aboiginal Healing Foundation. (2006a). Final Report of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation: Volume I A Health Journey: Reclaiming Wellness. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- AHF—Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2006b). Final Report of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation: Volume II Measuring Progress: Program Evaluation. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- AHF—Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2006c). Final Report of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation Volume III Promising Healing Practices in Aboriginal Communities. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- *Aho K.L., & Liu J.H. (2010). Indigenous suicide and colonization: The legacy of violence and the necessity of self-determination. International Journal of Conflict & Violence, 4(1):124-33.

- ANAC—Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada (2009). [Internet]. Cultural competence and cultural safety in First Nations, Inuit and Metis nursing. [cited 3 November 2010]. Available from: http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/Review_of_Literature_e.pdf.

- Arksey, H, & O’Malley, I. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1): 19-32.

- Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2014). The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(3), 320-338.

- Blackstock, C., Cross, T., George, J., Brown, I., & Formsma, J. [Internet] (2006). Reconciliation in Child Welfare: Touchstones of Hope for Indigenous Children, Youth, and Families. Ottawa, ON: First Nations Child & Family Caring Society of Canada/Portland, OR: National Indian Child Welfare Association. [cited 28 June 2015]. Available from: http://www.fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/Touchstones_of_Hope.pdf

- Brave Heart, M.Y. (2003). The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: a Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(1): 7-13.

- Brave Heart, M.Y., & DeBruyn, L. (1998). The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 8(2): 56-78.

- Brien, S.E., Lorenzetti, D.L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W.A. (2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5:2.

- Chalifoux, The Honourable Thelma & The Honourable Janis G. Johnston. (2003). Urban Aboriginal Youth: An Action Plan for Change. Final Report. Ottawa: Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples.

- Chouinard, J.A., Moreau, K., Parris, S., & Cousins, J.B. (2010). Special study of the National Aboriginal Youth Suicide Prevention strategy. Ottawa: Centre for Research on Evaluation and Community Services, University of Ottawa.

- Craib, K.J., Spittal, P.M., Patel, S.H., Christian, W.M., Moniruzzaman, A., Pearce M.E., et al. (2009). Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among Aboriginal young people who use drugs: results from the Cedar Project. Open Medicine, 3(4):e220-7.

- Crooks, C.V., Chiodo, D., & Thomas, D. (2009). Engaging and empowering Aboriginal youth: A toolkit for service providers. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- DeGagne, M. (2007). Toward an Aboriginal paradigm of healing: addressing the legacy of residential schools. Australasian Psychiatry, 15(Suppl 1):S49-53.

- *Dell, C.A., Seguin, M., Hopkins, C., Tempier, R., Mehl-Madrona, L., Dell, D., et al. (2011). From benzos to berries: treatment offered at an Aboriginal youth solvent abuse treatment centre relays the importance of culture. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry - Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 56(2): 75-83.

- Dunne, E. (2000). Consultation, Rapport, and Collaboration: Essential Preliminary Stages in Research with Urban Aboriginal Groups. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 6: 6-14.

- Evans-Campbell, T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: a multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3): 316-38.

- Freedenthal, S. & Stiffman, A. (2004). Suicidal behavior in urban American Indian adolescents: A comparison with reservation youth in a southwestern state. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(2): 160-71.

- *Gilder, D.A., Luna, J.A., Calac, D., Moore, R.S., Monti, P.M., & Ehlers, C.L. (2010). Acceptability of the use of motivational interviewing to reduce underage drinking in a Native American community. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(6):836-42.

- *Goodkind, J.R., Lanoue, M.D., & Milford, J. (2010). Adaptation and implementation of cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools with American Indian youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(6): 858-72.

- Guimond, E, & Cooke, M. (2008). The Current Well-being of Registered Indian Youth: Concerns for the Future? Horizons,10(1): 26-30.

- Health Canada. (2009). A Statistical Profile on the Health of First Nations in Canada: Self-rated Health and Selected Conditions, 2002 to 2005. Ottawa: First Nations and Inuit Health Branch.

- Health Canada (2011). First Nations and Inuit Health: Mental health and wellness [cited 27 October 2015]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fniah-spnia/promotion/mental/index-eng.php

- *Higgins, D.J. (2005). Indigenous community development projects: Early learnings research report. Vol. 2. Melbourne: Telstra Foundation.

- Hodge, D.R., Limb, G.E., & Cross, T.L. (2009). Moving from colonization toward balance and harmony: A Native American perspective on wellness. Social Work, 54(3): 211-9.

- *Holland, P., Gorey, K.M., & Lindsay, A. (2004). Prevention of mental health and behavior problems among sexually abused aboriginal children in care. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 21(2): 109-15.

- INIHKD—International Network of Indigenous Health Knowledge and Development [Internet]. (2010). Indigenous Wellness Research Institute; [cited 28 August 2010]. Available from: http://www.iwri.org/inihkd/.

- Israel, B.A., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A., & Becker, A.B. (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. TheAnnual Review of Public Health, 19:1 73-202.

- Jaycox, L. (2004). CBITS: Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools. Longmont, CO: Sopris West Educational Services.

- Kania, A., Patel, A., Roy, A., Yelland, G., Nguyen, D., & Verhoef, M. (2013). Capturing the complexity of evaluations of health promotion interventions: A scoping review. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 27(1): 65-91.

- Kirmayer, L.J., Brass, G.M., & Tait, C.L. (2000). The mental health of Aboriginal peoples: transformations of identity and community. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry - Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 45(7): 607-16.

- *Lafreniere, G., Diallo, P.L., Dubie, D., & Henry, L. (2005). Can university/community collaboration create spaces for Aboriginal reconciliation? Case study of the Healing of the Seven Generations and Four Directions community projects and Wilfrid Laurier University. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 2(1): 53-66.

- *Lowe, J. (2006). Teen Intervention Project--Cherokee (TIP-C). Pediatric Nursing, 32(5): 495-500.

- Lowe, J. (2002). Balance and harmony through connectedness: the intentionality of Native American nurses. Holistic Nursing Practice, 16(4): 4-11.

- Mable A.L., & Marriott J. (2001). A path to a better future: a preliminary framework for a best practice program for Aboriginal health and health care. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- *Marlatt, G.A., Larimer, M.E., Mail, P.D., Hawkins, E.H., Cummins, L.H., Blume, A.W., et al. (2003). Journeys of the Circle: a culturally congruent life skills intervention for adolescent Indian drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 27(8): 1327-9.

- Martin, D. (2012). Two-eyed seeing: a framework for understanding indigenous and non-indigenous approaches to indigenous health research. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(2):20-42.

- Menzies, P. 2006. Intergenerational trauma and homeless Aboriginal men. Canadian Review of Social Policy, 58:1-24.

- Morse, J.M., & Niehaus, L. (2009). Mixed method design: principles and procedures. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

- NAHO—National Aboriginal Health Organization. (2008). Cultural Competency and Safety: A Guide for Health Care Administrators, Providers and Educators. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- *Palmer, D., Watson, J., Watson, A., Ljubic, P,. Wallace-Smith, H., & Johnson, M. (2006). Going back to country with bosses: the Yiriman Project, Youth Participation and walking along with Elders. Children, Youth and Environments, 16(2): 317-37.

- Pearce, M.E., Christian, W.M., Patterson, K., Norris, K., Moniruzzaman A, et al. (2008). The Cedar Project: Historical trauma, sexual abuse and HIV risk among young aboriginal people who use injection and non-injection drugs in two Canadian cities. Social Science & Medicine, 66(11): 2185-94.

- Public Health Action Support Team [Internet] (2011). Grey literature [cited 27 October 2015]. Available from: http://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook/research-methods/1a-epidemiology/grey-literature

- Quinn, A. (2007). Reflections on intergenerational trauma: Healing as a critical intervention. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3: 722.

- Robinson, G, & Tyler, B. (2006). Ngaripirliga'ajirri: An early intervention program on the Tiwi Islands: Final Evaluation Report. Casuarina, Australia: School for Social and Policy Research, Charles Darwin University.

- Roy, A. (2014a). Intergenerational Trauma and Aboriginal Women: Implications for Mental Health during Pregnancy. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 9(1): 7-21.

- Roy, A. (2014b). Aboriginal worldviews and epidemiological survey methodology: overcoming incongruence. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 8(1): 134-45.

- Roy, A., Thurston W.E., Crowshoe L., Turner D., & Healy B. (2014). Research with, not on: Community-based Aboriginal health research through the “Voices and PHACES” study. In: Badry D., Fuchs D., Montgomery H.M., & McKay S., editors. Reinvesting in Families: Strengthening Child Welfare Practice for a Brighter Future: Voices from the Prairies. Saskatchewan: University of Regina Press, p. 111-32.

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Research in Nursing & Health, 23: 246-55.

- *Shantz, J. (2010). The foundation of our community: Cultural restoration, reclaiming children and youth in an indigenous community. The Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law, 32(3): 229-36.

- *Skye, W. (2002). E.L.D.E.R.S Gathering for Native American Youth: Continuing Native American Traditions and Curbing Substance Abuse in Native American Youth. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 29(1): 117-35.

- Smith, D, Varcoe, C, & Edwards, N. (2005). Turning around the intergenerational impact of residential schools on Aboriginal people: Implications for health policy and practice. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 37(4): 38-60.

- Sotero, M. (2006). A Conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1(1): 93-108.

- Strickland, C.J., Walsh, E., & Cooper, M. (2006). Healing fractured families: Parents' and elders' perspectives on the impact of colonization and youth suicide prevention in a Pacific Northwest American Indian tribe. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17(1): 5-12.

- Struthers, R., & Lowe, J. (2003). Nursing in the Native American culture and historical trauma. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 24(3):257-72.

- Thurston, W.E., Oelke, N.D., & Turner, D. (2013). Methodological challenges in studying urban Aboriginal homelessness. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 7(2): 250-9.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. [Internet] (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future : Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [cited 27 June 2015]. Available from: http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Exec_Summary_2015_06_25_web_o.pdf

- *Tsey, K., Whiteside, M., Haswell-Elkins, M., Bainbridge, R., Cadet-James, Y., & Wilson, A. (2010). Empowerment and Indigenous Australian health: A synthesis of findings from family well-being formative research. Health & Social Care in the Community, 18(2): 169-79.

- *Veroff, S. (2002). Participatory art research: Transcending barriers and creating knowledge and connection with young Inuit adults. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(8): 1273-87.

- Wesley-Esquimaux, C, & Smolewski M. (2004). Historic Trauma and Aboriginal Healing. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- *Wexler, L.M. (2006). Inupiat youth suicide and culture loss: Changing community conversations for prevention. Social Science & Medicine, 63(11): 2938-48.

- Whitbeck, L.B., Adams, G.W., Hoyt, D.R., & Chen, X. (2004). Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(3-4): 119-30.

- World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet] (1986): Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion [cited 12 September 2008]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf.

[Note: The 16 papers included in the scoping review are marked with an asterisk]

List of tables

Table 1

Search terms and database hits

Table 2

Summary of characteristics of 16 papers reviewed

Table 3

Summary of recommendations made in papers

10.7202/1069538ar

10.7202/1069538ar