Abstracts

Abstract

In 2008, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Inuit Tuttarvingat of the National Aboriginal Health Organization collaborated to provide input to national discussions of research ethics and processes in the Canadian Arctic. This paper describes the work of Inuit Nipingit (National Inuit Committee on Ethics and Research) during two years from 2008 to 2010. The Inuit Nipingit committee was concerned with research and its ethics environment as faced by Inuit as research participants, researchers, and those being consulted on research proposals. Members of this national committee discussed Canada’s ethical guidelines for research and responded to a call for input into the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. In an effort to support capacity building, Inuit Nipingit also produced reference materials for Inuit community members and anyone concerned in research involving Inuit.

Résumé

En 2008, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami et Inuit Tuttarvingat de l’Organisation nationale de la santé autochtone collaborèrent afin de contribuer aux débats nationaux sur l’éthique et les processus de la recherche dans l’Arctique canadien. Cet article décrit les travaux qu’Inuit Nipingit (Comité national inuit sur l’éthique et la recherche) a menés durant deux ans, de 2008 à 2010. Le comité d’Inuit Nipingit se préoccupait de la recherche et de son cadre éthique tels qu’ils se présentaient aux Inuit en tant que participants, chercheurs ou ceux consultés concernant des propositions de recherche. Les membres de ce comité national ont discuté des lignes directrices sur l’éthique dans la recherche émises par le Canada et ont répondu à une consultation de l’Énoncé de politique des trois Conseils: Éthique de la recherche avec des êtres humains . Dans le souci de soutenir le renforcement des capacités, l’Inuit Nipingit a également produit du matériel de référence destiné aux membres des communautés inuit et à toute personne concernée par la recherche impliquant des Inuit.

Article body

Introduction

The past decade has seen a sharp rise in the number of research projects conducted in Inuit Nunangat.[1] Meanwhile, there has been a corresponding increase in efforts to formulate guidelines and policy statements for research involving Inuit, First Nations, and Métis in Canada. These efforts include regional guidelines produced by regional Inuit governments, such as the Nunatsiavut Government Research Process document (Nunatsiavut Government 2010), as well as research agency efforts, such as the guidelines prepared by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) for research involving Aboriginal Peoples (CIHR 2007). Arctic researchers currently follow a number of guidelines for research involving Aboriginal Peoples (e.g., ACUNS 2003; CAA 1997; CIHR 2007; IASSA 1998; Owlijoot 2008; RCAP 1993). Canadian academic institutions follow the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS) (CIHR et al. 2010).

According to Inuit organisations and individuals working with researchers in Northern communities, there is room for systematic engagement of Inuit in preparing and defining ethical guidelines for research, particularly when carried out in Inuit Nunangat and involving Inuit. When the Tri-Council decided to update its original 1998 TCPS, the Inuit of Canada understood the importance of this decision and were greatly interested in joining the review process. They created Inuit Nipingit (National Inuit Committee on Ethics and Research) in 2008 as an advisory working group with members from each regional Inuit land claim organisation and specific Inuit organisations. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) and Inuit Tuttarvingat of the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO), both being Inuit-governed, committed to facilitating collaborative discussions of ethical conduct for research. ITK represents Inuit at the national level with a mission to help achieve the hopes and priorities of Inuit in Canada. Inuit Tuttarvingat of NAHO seeks to advance and promote the health and well-being of Inuit individuals, families, and communities by working within strong partnerships to collect information and share knowledge.

This paper describes Inuit Nipingit’s work during two years from 2008 to 2010. The work involved reviewing the draft 2nd edition of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2) and commenting on ways to improve the policy statement from an Inuit perspective. Funding came from the Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics (PRE) and was used to form the committee and arrange face-to-face meetings.

Figure 1

Map of Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland in Canada

Background on consultations leading to the TCPS2

The Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans is produced by Canada’s three federal research agencies: the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR), the National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). It outlines research standards and procedures for recipients of funding from CIHR, NSERC, or SSHRC. In 2008, consultations began for the first major review of the TCPS1 (1998) and, after significant changes to the original document, the new TCPS2 was released in December 2010.

The Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics (PRE) of the Tri-Council established a specific Aboriginal process and advisory committee for TCPS review, the Aboriginal Research Ethics Initiative (AREI). In 2008, the AREI presented a report on Section 6 of the TCPS which acknowledged the distinctness of Inuit, First Nations, and Métis populations, their increasing role in research, and the existence of ethical guidelines prepared by each of them (e.g., First Nations Centre of NAHO 2003, 2007a, 2007b; ITK and NRI 2007; Métis Centre of NAHO 2010) and set out an ethical framework for research involving Aboriginal Peoples (AREI 2008). The PRE solicited public input for a second edition of the TCPS from 2008 to 2010.

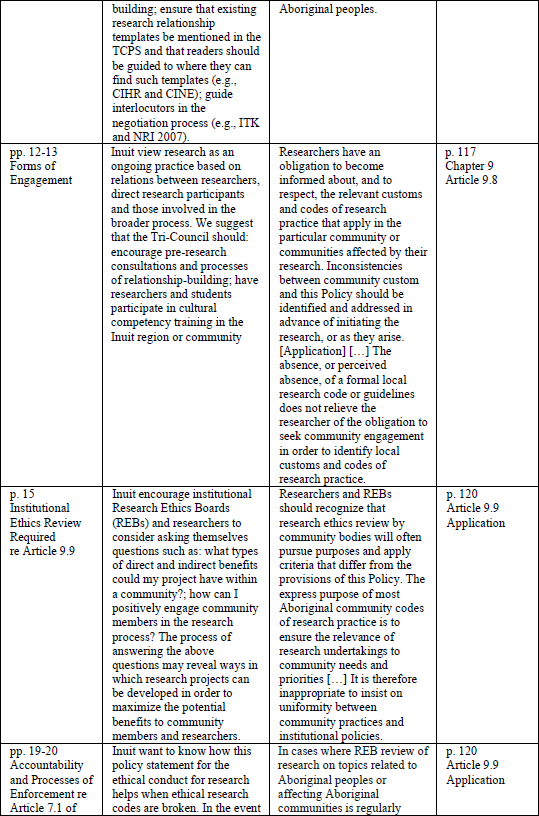

In the original 1998 TCPS 1st edition, Section 6, “Research Involving Aboriginal Peoples,” was intended to launch discussions about what constitutes appropriate research conduct involving Aboriginal individuals and communities. Although this section showed goodwill by including ethical considerations, it did not provide any content and/or concepts. In the new 2010 TCPS2, Section 6 was replaced with Chapter 9, “Research involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada.” It took a major step forward by adding key concepts and definitions for ethics and Aboriginal research, by incorporating examples of Aboriginal-related research, and by recognizing Inuit, First Nation, and Métis Peoples as distinct populations. While its provisions govern research involving First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, Aboriginal communities also may establish and apply their own codes of research practice. The TCPS2 states that “[i]t is not intended to override or replace ethical guidance offered by Aboriginal peoples themselves” (CIHR et al. 2010: 105). There is thus room for principles and codes that Aboriginal entities have already implemented at the local, regional, and national levels. For a summary of major changes, see Table 1.

The Inuit Nipingit committee was formed to comment on the draft 2nd edition of the TCPS (released in December 2008) and, in particular, Chapter 9 (“Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada”). As an Inuit advisory group, Inuit Nipingit was to provide input to research in the Canadian Arctic, identify emerging research priorities, improve and enhance networking, and facilitate knowledge translation. In recognition of Inuit interests in improving and maintaining appropriate research conduct and processes, Inuit Nipingit would respond to identified Canadian policy statements and guidelines, and prepare Inuit positions as necessary. Such responses were needed to the recent establishment of a Canadian High Arctic Research Station by the federal government and the creation of Inuit Qaujisarvingat (The Inuit Knowledge Centre at Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami). Furthermore, Inuit regional organisations and governments had become interested in accessing information and research results and in discussing ownership, storage, and use of research materials.

Inuit Nipingit had 17 members, with 12 appointed by regional Inuit land claim organisations or governments: Inuvialuit Regional Corporation; Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated; Makivik Corporation; Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services; and the Nunatsiavut Government. Three committee seats were assigned to each Inuit region, and one to each of the following national Inuit organisations: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; Inuit Circumpolar Council; Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada; National Inuit Youth Council; and Inuit Tuttarvingat of NAHO. In addition, the committee had seven observers with special expertise, such as in research licensing and academic research on specific subjects. As agreed in the Terms of Reference (Inuit Nipingit 2009), Inuit Nipingit was given the following goals:

be active in helping Inuit get involved in and take positions on research and research ethics at the community, regional, national, and international levels;

develop effective responses to identified Canadian policy statements and guidelines and prepare Inuit positions as necessary;

raise awareness of research ethics; and

enhance understanding of research on Inuit lands and communities and research involving Inuit.

Table 1

Evolution of Section 6 of TCPS1 into Chapter 9 of TCPS2.

Identifying Inuit priorities

Inuit Nipingit discussed an initial literature review and identified several common concerns—both national and global—regarding the ethics of research involving Indigenous Peoples: acknowledgement and recognition of treaty rights; land claims and Inuit jurisdiction; protection and recognition of Indigenous cultural knowledge, rights, and heritage, and of elders’ specific knowledge of traditional laws; recognition of the value of collaborative practice in research involving Indigenous peoples and communities; and recognition of knowledge sharing between researchers and individuals, communities, regions, and governments. The literature also frequently mentioned Aboriginal approaches to research, data, and information management (First Nations Centre of NAHO 2007a). Clearly, many Inuit concerns had been written about. In the literature we find particular mention of community involvement and partnerships but not of some other themes important to Inuit, such as wildlife and linkages to the environment.

Inuit Nipingit identified the following concerns as important to Inuit:

intangible cultural property[2] (i.e., respecting language, traditional knowledge);

community empowerment (i.e., balancing powers between researchers and communities, communities to share in the benefits of research);

effects on communities and regions (i.e., increasing positive outcomes and reducing negative ones);

knowledge sharing between researchers and individuals, communities, regions, and governments (i.e., engaging in meaningful communication when sharing research results; understanding knowledge sharing as part of a research project); ethical issues on the treatment of animals in the research process and/or methods (i.e., respecting the relationship between humans and other species and considering relationships in a broader environmental context); and

preparation of a fundamental document about the Inuit position on research, this being necessary because 1) research with Inuit participation and/or in Inuit regions is continually increasing; 2) Inuit have learned from experience that they have to get involved in research if they want it to be favourable to them.

Inuit Nipingit completed its review by April 2010 and submitted the above list of concerns, along with comments and recommendations to the Panel on Research Ethics of the Tri-Council. Following the dichotomy of substance and procedure as practised in law, the committee separated the concerns into two types: those that address the procedure (process) of research and those that deal with areas of substance (content). Procedure means the proper way to evaluate research projects, i.e., “how” to protect. Substance means whatever Inuit want to protect or promote. We present Inuit Nipingit’s concerns in the following sections, separating them by procedure and by content.

Procedural recommendations by Inuit Nipingit

Inuit Nipingit made several procedural recommendations to the Tri-Council for the redrafting of Chapter 9.[3]

Population-specific approach

Inuit Nipingit recommended that the Tri-Council consider providing separate and consistently ordered Inuit, First Nations, and Métis examples in Chapter 9. It argued that Inuit would like to see a population-specific approach in most types of research, with results showing Inuit-specific data and statistics. Without such information the Inuit cannot influence policy development to their benefit. Because Chapter 9 represents broad pan-Aboriginal interests, it cannot always promote sound culture-specific data gathering.

Partnership in research

Inuit Nipingit felt it essential to promote the principle of “relationship” in research with Inuit communities. It suggested that the Tri-Council should 1) ensure that the TCPS strongly support the importance of research as relationship building; 2) ensure that existing research relationship templates be mentioned in the TCPS, and that readers be told to where to find them (e.g., CIHR); and 3) guide those who act as interlocutors in negotiating research relationships with Inuit communities (ITK and NRI 2007).

The rationale was that researchers are increasingly encouraged to engage Inuit communities, and such engagement requires both sides to negotiate a research relationship whereby they jointly define their respective roles and responsibilities, outlining mutual benefits and expectations. Research relationships mean different things in different contexts. In some instances, where the fieldwork needs direct community involvement and where the community wants to be involved, both parties may wish to draw up a formal research agreement. In others, individual consent might be given orally while at the same time written agreements are used to formalise relationships with multiple community institutions.

Inuit see research as relationship development, where trust is built over time, and this, they feel, should be reflected more strongly in the TCPS document. A national policy like the TCPS must have concise statements of what protection it provides in order to level the playing field and give substance to the words of research relationships with Inuit communities, with non-Inuit , and with non-human species. Inuit are interested in promoting long-term research programs where the important phase of research planning and trust building between researchers and community can be nurtured. A better researcher-community relationship will lead to even better research results.

Pre-research consultations and relationship building

Inuit Nipingit suggested that the Tri-Council should encourage pre-research consultations and processes of relationship building, and promote earmarking of dedicated funds for this purpose. Some Inuit are concerned about the conduct of research and about the community impacts. Some of the concern stems from lack of consultation in identifying research needs and questions and in designing studies. Inuit often feel they are not adequately involved throughout the research process (e.g., project design, data collection and analysis, and communication of results). Occasionally Inuit dismiss scientific studies (especially those on harvested wildlife species) as unnecessary, inaccurate, and irrelevant. A common perception is that Inuit often already have the answers to many research questions and that all the researcher needs to do is ask.

Inuit Nipingit agreed with the Revised Draft 2nd Edition TCPS statement “[w]here the social, cultural or linguistic distance between the community and researchers from outside the community is significant, the potential for misunderstanding is likewise significant” (CIHR et al. 2008: lines 3527-3629).[4] To prevent misunderstanding, researchers should be more flexible with their time and allow for preliminary consultation with community residents, before the project begins. If a researcher is new to Aboriginal settings, he or she needs time to “know” the community, to become familiar with its members and environment, and to gain trust and respect, with no pressing agenda. The Revised Draft 2nd Edition states a little less directly that,

Engagement between the community involved and researchers, initiated prior to the actual research activities and maintained over the course of the research, can enhance ethical practice and the quality of research. Taking time to establish a relationship can promote mutual trust and communication, identify mutually beneficial research goals, define appropriate research collaborations or partnerships, and ensure that the conduct of research adheres to the core principles of justice, respectful for persons and the concern for welfare of the collective, as understood by all parties involved.

CIHR et al. 2008: lines 3529-3535, our emphasis

This is a laudable statement, but Inuit are concerned that it may only be a statement and not a policy that is implemented. To what degree is this prior engagement actually provided for and cultivated within the Tri-Council funding mechanisms? Can funding recipients actually conduct their research in this recommended way? Unfortunately, university research design, funding agencies, and research programs do not typically allow for this preparatory period.

Cultural competency training

Inuit Nipingit suggested that the Tri-Council should have researchers and students participate in cultural competency training in the Inuit region or community. The committee explained the need to engage local community members in order to identify appropriate research processes, to maximise local participation, and to produce meaningful research results. The researcher and community members could jointly create a steering or advisory group and identify community-based individuals who will be trained in research or research-related tasks. Before, during, and after research, the researcher should explain the benefits to the community and accommodate Inuit priorities as much as possible.

Inuit Nipingit further noted that some research programs are of short duration and geared to fast completion of university training. Because students lack sufficient time to become familiar with or achieve cultural competencies, the community is under much pressure and the quality of research might suffer (e.g., as with students doing a one-year master’s program). An example of good practice is found at the Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment (CINE), where master’s students are integrated into existing larger projects and scheduled for pre-research visits in the communities. In this way, student-researchers of different cultural backgrounds can gain appropriate regional and cultural training by using community and regional resources or existing regional materials.

Implementation of possession agreements

Inuit Nipingit suggested that the Tri-Council should encourage implementation of data possession agreements as the communities develop the required resources (logistics, capacities, etc.). The First Nations Centre of NAHO, for example, has adopted a code of principles that supports control by First Nations over data collection in their communities. First Nations own, protect, and control how information is used. They determine, under appropriate mandates and protocols, how access can be facilitated and respected. These are the OCAP principles for research, i.e. Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession. Possession refers to the physical control of data, a means by which ownership is protected:

While ownership identifies the relationship between a people and their data in principle, possession or stewardship is more literal. Although not a condition of ownership per se, possession (of data) is a mechanism by which ownership can be asserted and protected. When data owned by one party is in the possession of another, there is a risk of breach or misuse. This is particularly important when trust is lacking between the owner and possessor.

First Nations Centre of NAHO 2007a: 5

Although Inuit have not signed on to the OCAP principles, they need to discuss such principles and in particular that of possession. This principle means that Inuit communities can control the use of data stored in a database and use such data for their own research initiatives (ITK 2008). The principle of possession has to apply to all research and to all forms of data or biological collection.

Inuit Nipingit suggested that Inuit possession can best be established by a possession agreement, which may be a memorandum of understanding between the researcher’s institution and the community or the representative land claims organisation. This agreement is distinct from the research agreement. Its content can continue to apply long after a research project has ended. The possession agreement could be gradually introduced, as communities develop the resources required for its implementation. Its existence would be compulsory if required by the community that hosts a research project.

Privacy

The Canadian Constitution’s fundamental rights and freedoms include privacy protections, and researchers have a duty to respect them. Inuit Nipingit realises that protection of anonymity is difficult in small Inuit communities where each person knows everyone else. Thus, when a research project gathers sensitive personal information on human health[5] or political issues, the participants will need protection if other residents can easily identify their participation.

Even when the data are aggregated, specific individuals can be identified because there are so few participants overall. When participants do not want to be identified and/or when sensitive personal information is gathered, the results need to be kept confidential. Inuit Nipingit strongly recommended that researchers guarantee the protection of participant privacy in such cases during data gathering and afterwards, when the results are disclosed.

Consent

Inuit Nipingit made recommendations on three areas of concern: 1) informed voluntary consent, 2) appropriate age of consent, and 3) double or multiple consent.

1) Informed voluntary consent

Informed voluntary consent means that participants have been informed of the risks and benefits of the research processes and, after having thought over the information provided to them, have voluntarily agreed to participate. Clarity of format and wording is essential on written consent forms and should be translated into the Inuit language of the community. Verbal consent may be an appropriate option. Participants must be provided with the researcher’s contact information, a project description, how the participant will be involved, and how the collected data will be treated and used.

2) Appropriate age of consent

There is need for awareness of cultural norms when assessing the age of consent. Expressions of autonomy and decision making can differ from one culture to another, and such differences should be considered when designing the TCPS. Definitions of youth in the Arctic are broad and subject to interpretation. For example:

The International Institute for Sustainable Development, in co-operation with the secretariat for the Future of Children and Youth of the Arctic (supported by the Arctic Council) recruits youth between the ages of 19 and 30 for internships within the circumpolar north.

The Role Model Program of the National Aboriginal Health Organization targets Canadian Aboriginal youth between the ages of 13 and 30.

The Government of Canada initiatives that target Inuit youth (e.g., the Youth Employment Strategy) accept applications from Canadian Inuit between the ages of 15 and 30.

The Inuit Circumpolar Youth Council and the National Inuit Youth Council define youth as individuals between the ages of 16 and 30.

Given this variety, more work is clearly needed to define the age range of an Inuk youth and the age of consent. Further, these definitions may differ between regions.

3) Double or multiple consent

Often, double or multiple consent is required (individual and community). Broader consent from umbrella organisations or community representatives does not replace the necessity of individual consent. Nor does individual consent replace community consent. Even when the community representatives have permitted the project to go ahead, the researchers must still obtain consent from each individual willing to participate. Researchers should not assume that an individual’s consent means community consent. Inuit Nipingit stressed the need for an efficient and effective system for community-level review of research proposals.

Recommendations by Inuit Nipingit on substance

Substance means whatever Inuit want to protect or promote. Discussions among Inuit Nipingit members revealed a need to address capacity building, consultation with women, wildlife, food security, and traditional knowledge. These five themes are not necessarily the only Inuit concerns of substance, but they were the ones that the committee identified within the constraints of time and other resources.

Capacity building

“Capacity building” has emerged as an important concept in international development. It means strengthening the knowledge, abilities, and leadership of people and communities in developing societies so that they may overcome the obstacles to their needs and goals. In the Arctic many researchers have visited Inuit communities and returned to their universities, finished their degrees, and moved on with their academic careers without further contact. Inuit have seen many researchers come and go, often without a clear understanding of what the researcher actually did. While researchers can use fieldwork data to publish articles, to receive media exposure, and to comment about the researcher-Inuit relationship, Inuit seldom benefit in the same ways.

To help Inuit benefit from research projects, the Inuit Nipingit members called for an evolving research process that would enable Inuit to conduct their own research. For example, in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, capacity building needs to be clearly outlined in each research proposal before the regional Inuvialuit organisation can give a positive review. In this context, capacity building is a necessity that, to Inuit, may mean the following:

Inuit are involved in the research project from the beginning;

The research team leaves resources and/or equipment with the community after the research project has been completed;

Researchers help build and/or improve existing research facilities;

More programs combine traditional knowledge and academic skills;

Researchers and others provide space and opportunity to share knowledge and information. This includes acknowledging and treating Inuit experts in certain knowledge areas at an equal level as academic experts, helping institutionalise traditional knowledge (such as the Nunavut cultural school Piqqusilirivvik in Clyde River) and validating Inuit knowledge by accrediting elders in universities;

Viable and rigorous community-level review of research projects is established; and

The university Research Ethics Boards consider Inuit and Arctic-specific perspectives in their review processes.

For the International Polar Year 2007-2008—one of the latest multidisciplinary research initiatives, all Canadian-funded research proposals had to prove the “suitability of plans to communicate with Northerners” and describe “training opportunities for Northerners, particularly for Aboriginal people” (IPY 2007). One may assume from the inclusion of this requirement that current research processes acknowledge the need for more inclusive and partnership-based research. Has this goal been reached? Answering this question will require further evaluation, in particular from a community perspective.

Consultation with women

There are differences in life experiences between Inuit men and women. Inuit women intimately know the conditions of life in their communities. They are an integral part of the cultural perspective and knowledge traditions that constitute the Inuit universe. By including them in the themes, processes, and results of research, one can collect knowledge not gleaned elsewhere and produce specific impacts on Inuit women.

For example, such inclusion can improve research on access to health services for childbirth. Health research often focuses on identifying health needs, and the resulting data are crucial to health care planners and clinicians who serve women. Inuit women have also expressed their feeling that health care systems are not meeting their needs (Ajunnginiq Centre of NAHO 2006). They have limited access to health services in Inuit regions, and most of them must still leave their home community and spend time in a hospital far from home before giving birth. Even diagnostic tests that would mean a few hours for someone living in southern Canada might mean a flight and a trip lasting several days for someone living in one of the Inuit regions (Canadian Women’s Health Network n.d.). The Inuulitsivik midwifery program in Nunavik demonstrates that Inuit community-based initiatives are possible (Van Wagner et al. 2007). It also shows that childbirth is a family event. Isolating it from family and social ties has effects beyond the immediate clinical welfare of mother and child. Inuit midwives consider themselves family workers who take care of the mother and her child before and after delivery, but also assist to improve the well-being of families and communities.

No one can better express the health needs of Inuit women than Inuit women themselves. Including them in research goes beyond the specific issue of health care. As Inuit commonly point out, there are educational, subsistence, nutritional, and economic implications as well. Women should participate in all areas of research, such as climate change, wildlife, and environmental contamination, because their lives are often impacted differently. Indeed, gender is a key variable in socio-economic analysis. Inuit men and women also need to benefit from research equally.

Wildlife

According to Inuit Nipingit, there is a need to consider, document, and refer to existing regional protocols/guidelines for treatment of animals in wildlife research, as set out in most land claim agreements. A wildlife ethics policy is also needed. Ethical conflicts can emerge between cultures due to diverse wildlife and harvesting practices. Such conflicts might partly be rooted in differences in worldview and possibly result in questioning whether wildlife are a cultural property[6] or a cultural practice, i.e. subsistence hunting.

Treatment of animals in research

Inuit Nipingit noted deep cultural differences between the Inuit comprehension of human-wildlife relationships and that of academically trained researchers. In the committee’s discussions, treatment of animals by researchers was a high priority that requires further work and formulation. Inuit Nipingit wished to integrate the treatment of wildlife into guidelines for research involving humans, since many wildlife research practices are not congruent with Inuit cultural norms on how animals should be ethically treated. For example, the Inuit land claim organisation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. resolved in November 2007 that “members disapprove of intrusive wildlife research methods that are detrimental to wildlife and call on the Government to put a halt to detrimental survey and other research methods, and only use methods that are consistent with Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit [Inuit Knowledge]” (Nunavut Tunngavik 2007: 1). Although Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is most often translated as Inuit knowledge, it also encompasses values and ethical codes, and how and why things are done.

More recently, at the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Annual General Meeting in June 2009, a resolution expressed a

serious and increasing concern about the intrusive methods by which western science researchers are handling and gathering research data on polar bears that is causing stress and harm to the animals—namely through methods such as the use of tranquilizers, direct handling of the animal, taking body samples, collaring, paint marking, recapture, and using aircraft to track, chase, and seize the animals.

ITK 2009: 1

This resolution speaks to the connection between human health and treatment of animals by researchers. For example, wildlife researchers commonly recommend that a tranquillised animal should not be killed and consumed for a certain time that extends from several hours to several days. Inuit Nipingit has not yet conducted a thorough review of methods for chemical immobilisation of wildlife, but committee members are very interested in seeing one done in the near future. When wildlife undergo such research methods as the use of tranquillisers, concern focuses on 1) unknown health effects on wildlife (e.g., via sedative drugs); 2) unknown health effects on humans who have eaten meat from previously tranquillised animals; 3) inability to avoid hunting previously tranquillised animals because they are no longer distinguishable from other animals once the effects have worn off; and 4) effects of treatment, such as tranquillisation or repeated intrusive tagging, and their effects on human-animal relationships.

Anthropologists have stressed the need to consider not only Inuit values but also Inuit worldview in order to understand social relationships. Social norms and relations between human beings are “tied in with the norms pertaining to their dealings with nature. The acute, strong dependence on nature, animals in particular, had its pendant in the direct dependence on other people” (Rasing 1994: 269). Further, how an animal is treated can also affect other animals that Inuit have a relationship with. Thus, Inuit think that any research involving wildlife also directly involves themselves and other species. Given their intimate relationship with wildlife, Inuit feel that ethical treatment of animals is an issue that extends to humans as well—the two are, in a sense, inseparable. Inuit consider the handling of animals by researchers (especially in a repetitious manner), such as through physical interaction, chasing, tagging, and measuring, to be stressful for the animal and a source of physiological and psychological harm. To the Inuit, such handling may also have delayed negative consequences for humans. Animals may not make themselves accessible to Inuit hunters in the future because they have been treated with disrespect and because the human-wildlife relationship has been disturbed (e.g., Nuttall 2005).

Inuit Nipingit working for communities

Informing Inuit about research and research ethics issues is part of Inuit Nipingit’s mandate. Objectives include making Inuit front-line workers in regions and communities better able to deal with research and researchers, and thereby ultimately enhancing positive research outcomes while reducing negative ones. The committee has developed tools to assist and reach out to Inuit Research Advisors, who are positioned in each of the four Inuit land claims organisations and governments, and who already provide much needed support for researchers who intend to work in Inuit regions. A series of tools has been distributed to communities in an effort to reach research participants and to provide community offices with reference and training materials. To make information on research and research ethics available to community members, the following products have been developed:

A national poster titled “What is research?” that guides viewers to websites where the resources have been made available;

Webpages (www.naho.ca/inuit/research-and-ethics and www.itk.ca) that briefly introduce and describe each tool on the site;

A “Career as a Researcher” poster series that features region and topic-specific images accompanied by messages aimed at Inuit youth;

A “Research and Research Ethics Fact Sheet Series” that contains a total of nine pages on basic procedures, guidelines, and contacts. The series is a collection of living documents that are updated as necessary and added to as needed.

A “Research and Research Ethics Resource Binder” that includes materials useful for training of Inuit researchers and participants, such as Inuit Nipingit’s (2009) Terms of Reference and presentations, selected literature, guidelines, and “how to” fact sheets on research, such as templates for systematic literature searches and environmental scans (Inuit Nipingit 2010).

So far, these products have been used for training sessions, for on-the-job mentoring, and as reference material for community researchers and participants. Feedback from communities has included requests for additional copies of research ethics fact sheets and translations into Inuit languages. The posters have been much appreciated, and the use of regional photography lauded. In some cases, materials have been removed from their series and integrated into other information and training packages, an indication of their educational usefulness. In other cases, community members have inquired about training as researchers, expecting they can enrol immediately.

The new TCPS2 and recommendations by Inuit Nipingit

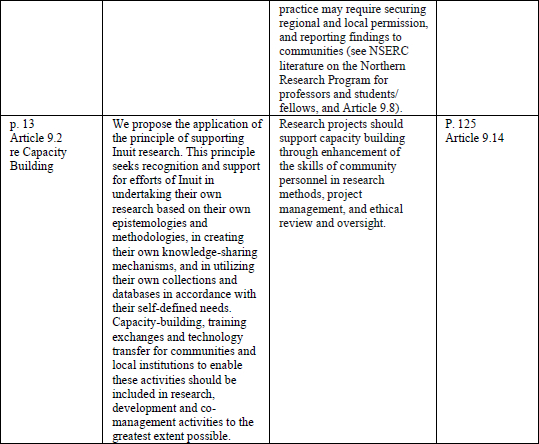

In December 2010, the 2nd edition of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2) was released and the original Section 6 on “Research Involving Aboriginal Peoples” had evolved into Chapter 9 “Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada,” acknowledging the distinctness of each population and offering substance and examples. Inuit-specific review and recommendations by Inuit Nipingit contributed to the revised TCPS2. Table 2 shows examples of provisions in the new TCPS2 that accommodate recommendations by Inuit Nipingit.

The TCPS2 (CIHR et al. 2010) is clear in describing the purpose and use of the document. In the introduction to Chapter 9, we read: “This chapter is designed to serve as a framework for the ethical conduct of research involving Aboriginal peoples. It is offered in a spirit of respect. It is not intended to override or replace ethical guidance offered by Aboriginal peoples themselves” (ibid.: 105). For Inuit, the review of the TCPS and the work in connection with the review have been a first step toward formulating at the national level what matters to Inuit in research and research ethics.

Table 2

Inuit Nipingit recommendations and the new TCPS2 (2010)

Conclusion

The process of creating a draft 2nd edition of the TCPS provided Inuit with a unique opportunity to help draw up Canadian research guidelines for federally funded research institutions. The work by Inuit Nipingit described here is a milestone in a long effort by Inuit to contribute to research and research ethics at the national level. Committee members represented the interests of community, regional, national, and international Inuit organisations, and ensured that views and comments covered as many angles and nuances as possible. The commitment of all members, including those with observer status, was outstanding and ensured the success of an ambitious two-year work plan.

Inuit regions will have to formulate research ethics and move toward Inuit-specific ethical evaluations of research. Inuit Nipingit members repeatedly stressed the need for an effective and efficient community-level system for review of research proposals. While community members are aware of this need and often go to great lengths to provide reviews in informal ways, there is a strong desire for institutionalisation of community reviews with assigned capacities and with opportunities for training and expertise development in research ethics. Overall, in continuation of the work of Inuit Nipingit, a number of items remain to be addressed:

Further elaboration of the work on topics of substance;

Establishment of a viable and rigorous community-level process for review of research proposals;

Inuit review of “Ownership, Control, Access and Possession” principles;

Development of a university Research Ethics Board process that considers Inuit and Arctic-specific perspectives; and

Establishment of an Inuit-specific Research Ethics Board.

Current research and political environments provide opportunities for further work on Inuit formulated ethical research guidelines as well as for discussion of Inuit ethical evaluations. The Inuit Qaujisarvingat: The Knowledge Centre of ITK, and Inuit Nipingit are well positioned to continue the work started by the latter by identifying, formulating, and promoting the procedure and substance Inuit want to see developed.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Inuit Nunangat is the term used to describe the homeland of the Inuit of Canada. In a contemporary political context, Inuit Nunangat can, with some minor qualifications, best be described as the land and marine areas that make up the land claims settlement areas of the Inuit of Nunatsiavut, Nunavik, Nunavut, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. Inuit Nunangat makes up approximately 40% of Canada’s land surface. It contains about one half of Canada’s coastlines, and encompasses virtually all of one territory (Nunavut), significant portions of one other territory (Northwest Territories), and two provinces (Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador). The literal translation of the Inuktitut singular phrase Inuit Nunangat is ‘Inuit land, and/or where Inuit live,’ inclusive of Inuit who reside in Southern centres.

-

[2]

According to the United Nations’ (2003) Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, the following domains are included here: oral traditions and expressions (includes language); performing arts (such as traditional music, dance, and theatre); social practices; rituals and festive events; knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; traditional craftsmanship.

-

[3]

The following text refers to the Revised 2nd Draft Edition of the TCPS (CIHR et al. 2008), i.e., the copy used for review. It differs considerably in document organisation and page number from the official TCPS2 released in December 2010.

-

[4]

Sections on community customs and engagement are found in the TCPS2 (CIHR et al. 2010: 108).

-

[5]

See First Nations Centre of NAHO (2005).

-

[6]

In Canada, Inuit have asserted ownership over the land and resources in their regions, and this ownership has translated into the right to use wildlife resources and to control how wildlife will be used. The government has accepted the Inuit claim to wildlife rights, and the resulting establishment of Inuit harvesting rights, self-regulating bodies such as hunters and trappers organisations, and co-management boards. While cultural property rights have been viewed as rights to objects, recent research on “common pool resources” (CPR) has provided an excellent model for group-level rights in communities. CPRs include any renewable or non-renewable good, e.g., fish and other wildlife, pastures, forest, light, wind, etc., from which it is difficult to exclude others (Saunders 2011).

Appendices

Remerciements

The authors would like to thank the Inuit Nipingit committee members and observers and ethicist Michel Giroux for sharing their knowledge, expertise, and time.

Reference

- ACUNS (ASSOCIATION FOR CANADIAN UNIVERSITIES FOR NORTHERN STUDIES), 2003 Ethical Principles for the Conduct for Research in the North, Ottawa, ACUNS (online at: acuns.ca/website/ethical-principles/).

- AJUNNGINIQ CENTRE OF NAHO, 2006 Exploring Models for Quality Maternity Care in First Nations and Inuit Communities: A Preliminary Needs Assessment, Ottawa, National Aboriginal Health Organization.

- AREI (ABORIGINAL RESEARCH ETHICS INITIATIVE), 2008 Issues and Options for Revisions to the Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct of Research Involving Humans (TCPS): Section 6: Research Involving Aboriginal Peoples, Ottawa, AREI (online version at: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/policy-politique/initiatives/docs/AREI_-_February_2008_-_EN.pdf)

- CAA (CANADIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION). , 1997 Statement of Principles for Ethical Conduct Pertaining to Aboriginal Peoples, Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 21(1): 5-6.

- CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK , n.d. Inuit Women’s Health. A Call for Commitment, Ottawa, Canadian Women’s Health Network (online at: www.cwhn.ca/en/node/39576).

- CIHR (CANADIAN INSTITUTES OF HEALTH RESEARCH), 2007 CIHR Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People, Ottawa, Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

- CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC (CANADIAN INSTITUTES OF HEALTH RESEARCH, NATURAL SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA and SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA), 2009 Revised Draft 2nd Edition of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS), December 2009.

- CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC (CANADIAN INSTITUTES OF HEALTH RESEARCH, NATURAL SCIENCES AND ENGINEERING RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA and SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA), 2010 Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct For Research Involving Humans, December 2010.

- CINE (CENTRE FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ NUTRITION AND ENVIRONMENT), n.d. Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment’s web site: http://www.mcgill.ca/cine/

- FIRST NATIONS CENTRE OF NAHO, 2003 Ethics Tool Kit: Ethics in Health Research, Ottawa, National Aboriginal Health Organization (online at: http://www.naho.ca/documents/fnc/english/FNC_ EthicsToolkit.pdf ).

- FIRST NATIONS CENTRE OF NAHO, 2005 Privacy Tool Kit: The Nuts and Bolts, revised version, Ottawa, National Aboriginal Health Organization (online at: http://www.naho.ca/documents/fnc/ english/FNC_PrivacyToolkit.pdf ).

- FIRST NATIONS CENTRE OF NAHO, 2007a OCAP: Ownership, Control, Access and Possession, sanctioned by the First Nations Information Governance Committee, Assembly of First Nations, Ottawa, National Aboriginal Health Organization (online at: http://cahr.uvic.ca/nearbc/documents/2009/FNC-OCAP.pdf).

- FIRST NATIONS CENTRE OF NAHO, 2007b Considerations and Templates for Ethical Research Practices, Ottawa, National Aboriginal Health Organization (online at: http://www.naho.ca/documents/fnc/english/ FNC_ConsiderationsandTemplatesInformationResource.pdf).

- IASSA (INTERNATIONAL ARCTIC SOCIAL SCIENCES ASSOCIATION), 1998 Guiding Principles for the Conduct of Research, Copenhagen, IASSA.

- INUIT NIPINGIT, 2009 Terms of Reference, approved February 18, 2009, Ottawa, Inuit Nipingit.

- INUIT NIPINGIT, 2010 Research and Research Ethics Fact Sheet Series, Ottawa, Inuit Tuttarvingat of the National Aboriginal Health Organization and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (online at: www.inuitknowledge.ca/content/research-and-research-ethics-fact-sheet-1).

- IPY (INTERNATIONAL POLAR YEAR), 2007 Frequently Asked Questions, International Polar Year 2007 (web page at: http://www.ipy-api.gc.ca/pg_ipyapi_008-eng.html#q3.2)”

- ITK (INUIT TAPIRIIT KANATAMI), 2008 Inuit Health and Environment Research Forum, Ottawa, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

- ITK (INUIT TAPIRIIT KANATAMI), 2009 ITK Annual General Meeting June 10, 2009, Nain, Nunatsiavut. Resolutions, Ottawa, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (online at http://www.itk.ca/sites/default/files/private/2009-en-itk-agm-resolutions.pdf).

- ITK (INUIT TAPIRIIT KANATAMI) and NRI (NUNAVUT RESEARCH INSTITUTE), 2007 Negotiating Research Relationships with Inuit Communities: A Guide for Researchers, Scot Nickels, Jamal Shirley and Gita Laidler (eds), Ottawa, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Iqaluit, Nunavut Research Institute (online at: http://www.itk.ca/sites/default/files/Negotitiating-Research-Relationships-Researchers-Guide.pdf).

- MÉTIS CENTRE OF NAHO, 2010 Principles of ethical Métis research, Ottawa, National Aboriginal Health Organization (online at: http://www.naho.ca/metis/current-work/ethics/).

- NUNATSIAVUT GOVERNMENT, 2010 Nunatsiavut government research process, updated May 2010, Nain, Nunatsiavut Government.

- NUNAVUT TUNNGAVIK, 2007 Intrusive Wildlife Research Methods. Resolution #A07-11-20, November 29, 2007, Iqaluit, Nunavut Tunngavik.

- NUTTALL, Mark, 2005 Hunting, herding, fishing and gathering: Indigenous Peoples and renewable resource use in the Arctic, in Robert Correll (ed.), Arctic Climate Impacts Assessment, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 649-690.

- OWLIJOOT, Pelagie, 2008 Guidelines for working with Inuit elders, Iqaluit, Nunavut Arctic College.

- PRE (PANEL ON RESEARCH ETHICS), 2008 Table of concordance - changes - Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS), 1998 Edition to Draft 2nd Edition 2008, Ottawa, Panel on Research Ethics, (online at http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/policy-politique/initiatives/docs/TOC%20-%20Old%20to%20New%20Version.pdf).

- PRE (PANEL ON RESEARCH ETHICS), 2009 Highlights of changes - Revised draft 2nd edition of the TCPS December 2008 – December 2009, Ottawa, Panel on Research Ethics, (online at http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/Revised%20Draft%202nd%20Ed%20PDFs/ Highlights%20of%20Changes_Revised%20Draft%202nd%20Ed%20TCPS%20(EN).pdf).

- PRE (PANEL ON RESEARCH ETHICS), 2010 Table of concordance – Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS), 1st Edition (1998) – TCPS 2 (2010), Ottawa, Panel on Research Ethics (online at http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2/TableofConcordance_1st_Ed_1998_to _2nd_Ed_2010.pdf).

- RASING, Willem C.E., 1994 Too Many People. Order and Non-conformity in Iglulingmiut Social Process, Nijmegen, KUFR.

- RCAP (ROYAL COMMISSION ON ABORIGINAL PEOPLES), 1996 Ethical Guidelines for Research, in Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, volume 5, Appendix 5, Ottawa, Government of Canada, (online at: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/webarchives/ 20071124125036/http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca /ch/rcap/sg/ska5e_e.html).

- SAUNDERS, Pammela Quinn, 2011 A Sea Change Off the Coast of Maine: Common Pool Resources as Cultural Property, Emory Law Journal, 60: 1323 (online at: http://ssrn.com/abstract =1701225).

- UNITED NATIONS, 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, Geneva, United Nations (online at: www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index. php?pg=00002).

- VAN WAGNER, Vicki, Brenda EPOO, Julie NASTAPOKA and Evelyn HARNEY, 2007 Reclaiming birth, health, and community: Midwifery in the Inuit villages of Nunavik, Canada, Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 52(4): 384-391.

List of figures

Figure 1

Map of Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland in Canada

List of tables

Table 1

Evolution of Section 6 of TCPS1 into Chapter 9 of TCPS2.

Table 2

Inuit Nipingit recommendations and the new TCPS2 (2010)