Abstracts

Abstract

By the late 1890s, mutoscopes were associated with “adult” material. Yet such displays were often accessible to children. Two sources of documentation, an 1899 Hearst newspaper campaign against “picture galleries of hell” and U.S. Farm Security Administration photographs of the 1930s, demonstrate the longevity of American children’s access to mutoscopes. The rhetoric of moral panic used in the Hearst campaign was short-lived and self-interested, but instructive in demonstrating how discourse on new media displays a similarly anxious tenor throughout the twentieth century. By contrast, the FSA photographs reveal that the perceived indecencies of the mutoscope were consigned to the margins by the 1930s.

Résumé

À la fin des années 1890, les mutoscopes étaient associés aux productions dites pour adultes. Pourtant, ces appareils étaient souvent accessibles aux enfants. Deux sources de documentation, la campagne du groupe de presse Hearst, en 1899, contre « les images des galeries de l’enfer », ainsi que les photographies de la Farm Security Administration, remontant aux années 1930, permettent d’établir la longévité de la fréquentation des mutoscopes par la jeunesse américaine. La panique morale qu’instillait la rhétorique des journaux de Hearst fut de courte durée et servit surtout les intérêts du groupe de presse. Elle demeure cependant fort instructive pour qui s’intéresse à la manière dont les discours sur les nouveaux médias diffusent une même angoisse au cours de tout le vingtième siècle. Au contraire, les photographies du FSA révèlent pour leur part que les indécences du mutoscope n’étaient ressenties comme telles que de façon marginale dans les années 1930.

Article body

By the late 1890s, mutoscopes were associated with “adult” material. Yet such displays were often accessible to children. Two sources of documentation, an 1899 Hearst newspaper campaign against “picture galleries of hell” and U.S. Farm Security Administration photographs of the 1930s, demonstrate the longevity of American children’s access to mutoscopes. The rhetoric of moral panic used in the Hearst campaign against the putatively deleterious mutoscope was short-lived and self-interested, but instructive in demonstrating how discourse on new media displays a similarly anxious tenor throughout the twentieth century. By contrast, the FSA photographs reveal that the perceived indecencies of the mutoscope were consigned to the margins by the 1930s, when the Main Street movie house was photographed as a safe haven for children, yet photos of rural fairgrounds attest to a youthful audience for salient mutoscope material.

The classical paradigm of cinema spectatorship—with its moviegoer sitting in a darkened theater, rapt in a narrative revealed via projected celluloid—has undergone persistent revision as film historiography has accumulated study after study complicating the generalizability this theory requires. A generation of scholarship in early cinema history has documented the diversity of practices that appeared in the first two decades of moving-image technology, the many paths picture viewing took before it became institutionalized as “the movies.” As Miriam Hansen suggests in her important essay, “Early Cinema, Late Cinema” (1993), the heterogeneity of media experiences in the late twentieth century makes the period akin to preclassical cinema. In revisiting the theorization of historical shifts between the moving image and its spectator audiences, the classical cinema may actually be seen as more of an exception than a norm.

Following both Hansen’s premise and the revisionist tendency of early cinema historiography, I offer this case study of mutoscope displays and their child viewers in the United States. The case begins with a conspicuous moment of public debate in 1899 but continues well into the era of classical Hollywood cinema. Three principal implications should be drawn from this case study. First, mutoscope exhibition was not merely a short-lived form of “precinema,” a novelty displaced by screen projection for mass audiences. It had a long life in city arcades, amusement parks and rural fairgrounds. As such, we need to account for the parallel history of this arcade world and that of the conventional movie theater. Second, we should further examine the particular exhibition practices and material conditions under which children saw these movies. The rhetoric about children and movie/media effects has been well chronicled in cinema and postcinema studies, particularly in social histories of the nickelodeon and classical Hollywood eras. But less attention has been given to documenting the particularity of children’s experiences, especially before the nickelodeon boom. Finally, my study aims to expand the types of primary and secondary resources historians use to understand early cinema and its successors. Even when using materials as traditional as periodicals, much film history has relied on trade journals and newspapers of record. As more detailed social histories have begun to emerge as scholars comb the pages of regional, small-town and minority publications, our understanding has grown richer.

Oddly, the period press that most often mentioned moving pictures and even used protocinematic technology—the so-called “yellow” or tabloid press—has been far less utilized than mainstream newspapers. Historians are well aware of the practices and impact of the Hearst newspapers, but these American dailies have been more difficult to access on microfilm and therefore neglected. This study looks at a “news cycle” about moving-picture machines in New York not found in the Times and other major papers. Additionally, I use another well-known resource—Farm Security Administration photographs—that has been little tapped by film historians. Looking at the collection’s large pool of documents, one finds a surprisingly direct and informative set of images that illuminate a phenomenon then three decades old. In using these photographs, many of them unpublished or incompletely identified, a new vein opens up through which evidence on moviegoing before World War II may be mined.

None of this suggests that we should abandon either the legacy of classical spectator theory or the study of mainstream moviegoing. However, it should compel us to continue our archaeology of abandoned cinema practices and to extend those findings to building improved theoretical explanations of media/audience relations. In the end, what remains most striking about the 1899 coverage of children viewing these so-called “immoral” mutoscopes is not the way that it presaged debates about the nickelodeon or the movies, but its uncanny similarity to the internet “indecency” rhetoric of the 1990s—another moral media panic based on unsupervised children viewing immoral images on individual screens.

Two Episodes in Peep-show History: 1899/1938

Shortly after their inception in the 1890s, peep-show movie displays in general and mutoscopes in particular became associated with “adult” material—stripteases, burlesque scenes, suggestive nudity. Yet, moreso than the theatrical adult films that followed them, motion pictures made for single-viewer devices were often accessible to children. The study of cinema has often neglected such orphaned technologies, sideline exhibition practices and lost viewing experiences. However, exceptions such as Brown and Anthony’s detailed History of the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company (1995) and Bob Klepner’s (1996) collection of materials from Australia reveal rich documentary evidence about mutoscope viewing.[1] Among such primary evidence in the history of mutoscope exhibition in the United States are two significant artifacts which I examine here. A series of nineteenth-century newspaper accounts and a set of photographs from the 1930s encompass the lifespan of the curious peep-show device; both specifically deal with the phenomenon of children as mutoscope spectators.

In 1899, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Evening Journal conducted a classic “yellow journalism” crusade against moving-picture machine operators in Manhattan. The notorious newspaper enlisted religious, civic and state leaders in a campaign blitzing what one headline called “picture galleries of hell,” an action that resulted in New York police shutting down these businesses and arresting a handful of early motion-picture merchants. A Journal illustration entitled “Gathering the Harvest of Indecency!” (figure 1) depicted a moneygrubbing exhibitor collecting coins from young boys and girls curious to see the “immoral” moving pictures hidden inside his peep-show cabinet.

In 1938, photographers working for the U.S. government’s Farm Security Administration recorded children going to movies, including three sets of youngsters gathered around peep-show machines. In the late thirties, FSA photodocumentarians were at the height of their travels across America, chronicling daily life on the nation’s city sidewalks, rural roads, and small-town Main Streets. Movie theaters, of course, had become an integral part of everyday life. Among the thousands of images the FSA captured were dozens depicting children as filmgoers—lining up for matinees, studying poster displays and, occasionally, peeking into mutoscopes. Russell Lee in particular took many such photos. One stands out. Lee’s remarkable 1938 snapshot, “Boys Looking at Penny Movies” (figure 2), suggests how much attitudes about children and motion pictures had changed in a generation. Main Street movies were predominantly safe, clean and well policed. Only the archaic peep-show held the threat of indecency.

Figure 1

New York Evening Journal, November 29, 1899

Figure 2

Russell Lee’s Boys looking at penny movies at South Louisiana State Fair. Donaldsonville, Louisiana, October 1938.

The 1899 conflict between motion-picture exhibitors and civic authorities is a neglected historical episode that prefigured the better-known incidents surrounding nickelodeons a decade later. However, I want to compare press coverage of this incident not to the policing discourse of Progressivism, but to the mute photographic evidence of 1938, which reveals the subaltern practice of mutoscope viewing continuing decades after it was displaced by theatrical filmgoing. Press coverage of 1899 “picture galleries” reads like a prototype for the discourse about moving pictures that proliferated during the nickelodeon boom. The Hearst crusade, although a minor incident, suggests how public perceptions of movie shows were primed before the more pronounced discourse against “immoral pictures” appeared after 1905.

The Hearst Press vs. Moving Picture Machines, 1899

The scare headlines of the New York Journal hardly provide pure empirical evidence. In fact, the articles bare an amazing similarity to the tone and tactics of the yellow press as fictionally immortalized in Citizen Kane (1941). The front-page headlines generated in a week of coverage by Hearst editor Arthur Brisbane show the crusading tabloid at its peak, grabbing for circulation. November 28, 1899: “Picture Dives Close in Panic;” November 29: “Moral Forces Close Picture Dives,” followed by “Journal’s Searchlight Closes Dives;” and a self-congratulatory closer on December 1st: “Evening Journal Wins After Quickest Crusade on Record.”[2] (One cannot but hear the voice of Charles Foster Kane’s ex-guardian, Mr. Thatcher, reading a montage of Kane’s breathless Inquirer headlines: “Traction Trust Exposed.” “Traction Trust Bleeds Public White.” “Traction Trust Smashed by Inquirer.”)

Yet the Journal’s articles, despite their tabloid qualities, are useful to the historian for their particularity. They list specific addresses where moving pictures were displayed, naming gallery owners and the parties arrested. The accounts also feature detailed descriptions of the conditions inside and outside of these establishments. Although the motion pictures themselves remained the target of the attacks, these accounts suggest that the pictures were principally used as bait to lure patrons, particularly children, into more carny-like, dime-museum attractions. Such shows typically included live performances by women dancing or posing. But these “living pictures” were of little concern to the Hearst exposé writer. Rather it was the “vulgar and suggestive pictures,” the peep-show images of “indecent” and “obscene” material, that the newspaper framed as the real corrupting force and moral danger. For five days the Journal poured on the invectives, insisting that these picture displays were “more numerous than the schools or the churches.” But at no time did it report or describe exactly—or even vaguely—what could be seen on these early moving-picture screens. Presumably the content featured some display of the female body, but this is never specified. Readers were never told “what the butler saw.”[3]

What, then, did the Journal’s series of exposés uncover? After a police raid on two New York businesses where “improper moving pictures were exhibited,” the Journal reported, no appropriate crackdown was forthcoming. So the reporter submitted his findings for the police and a reading public. A half dozen addresses on the Bowery were implicated. Their names connoted the faux-sophisticate, exotic show world of Gotham: the Moorish Palace, the Gaiety Museum, the Parisian Beauty Show, La Tosca, and the Oriental Palace. But the phenomenon was not segregated to the low end of the Bowery. Other picture galleries were singled out from 125th Street in Harlem to the heart of Broadway.

At the Moorish Palace, the report noted the typical gaudy signs that attracted patrons with “Free! Step In!”. Pictures of stage stars filled a window display. Roughly painted images of “Oriental women in poses” and “dancing girls” covered the storefront. Just inside the door, a “lecturer” hailed passersby with his barker spiel, as “a score of boys stood with their mouths agape.” He promised, for a nickel, wonders that the law would not permit him to show on the street. The reporter followed the crowd inside, where he described a 20 x 30 foot room. Along two of the walls were “picture machines,” some priced at a penny, others five cents. What one saw in these, he wrote, was simply “too vulgar to be described.” The Moorish Palace show ended with three poses done by “a young woman in tights.”

At the Gaiety Museum, he found that “the feature” was “an exhibition of picture machines,” rather than the expected burlesque show. Machines lined each wall. After paying an admission fee, visitors had to pay five cents for each view. “The pictures cannot be described,” the report teased again; “But the art critic of the police force ought to find something to interest him.” The next stop the Journal found to be “the most Barnum-like exhibition.” A large sign proclaimed “Three of the Greatest Shows on Earth for 5 Cents: Moulin Rouge! Danse Du Ventre! Au Danse Plaisaire!” Inside, moving-picture machines lined three walls. “Most of them were vulgar,” he insisted. But the live leg show he dismissed as a tired convention. A small stage was installed along the fourth wall, where “the usual ‘fake’ dancer appeared.” Most of the male clientele were induced to pay an additional ten cents to see “the living head of a woman who was beheaded.” Fooled again, the jaded reporter wrote, as ticket holders were shown the same dancer’s head thrust through a sheet of newspaper.

La Tosca, a nickel show billed for “Men Only,” featured “a sad-faced woman who looked as though she would rather do honest housework.” The Oriental Palace similarly found a barker summoning customers to see his “collection of picture machines” and “a helpless-looking girl in tights.” Advertised as “A Warm Show for Cool People,” the Palace and its orientalist motif were mimicked by another Bowery museum a block away. An illustration of this nameless storefront accompanied a picture of the gaudy Moulin Rouge, with the caption “Two of Many Traps Closed by Evening Journal.” A banner proclaiming “Oriental Dancers” hung above the entrance, with dozens of posters and theatrical portraits attracting male customers.

However, it was “school children,” the report insisted, who were lured to these unpalatial dives “in droves,” becoming “victims to their pictures.” Finally and most suggestively, the Journal’s campaign announcement concluded by listing the names and addresses of thirteen grade schools that were “within the sphere of malignant influence of the Bowery shows.” The moral panic was completed by a letter from a minister, the Rev. Dr. John Josiah Munro, which ran in a box beneath the aforementioned illustrations, with the headline “Picture Galleries of Hell.” Identified as the “Chaplain of the Tombs,” Munro was indeed a prominent writer who lobbied for Christian social reform, later publishing books on his experiences with prisoners in New York’s infamous Tombs Prison. The editorial to which he loaned his name began with a claim even broader than the Journal’s about the effect of these peep shows: “One of the perils which threaten the moral development of young lives in this great city is the moving-picture machine. In the hands of vile men it has become a propagator of obscenity.” Munro offered the only hint about the content of the films under attack, saying that he and the YMCA Secretary had visited the stores that were exhibiting views of women. No further details were offered, except that these images polluted, degraded and demoralized. Charging a “conspiracy of silence” among no less than censor Anthony Comstock, the police and the clergy, Munro advocated immediate and total suppression: “A bonfire of their filthy trash.”

The following day, the Journal’s front page listed a series of police actions directed against the picture merchants in its “slot-machine crusade.” Two cigar store owners were arrested for showing censorable pictures. If the reports are to be believed, New York’s chief of police ordered his captains to investigate all of the moving-picture displays in their precincts. The paper again itemized the businesses that were either raided by police or closed up to avoid prosecution. The Gaiety Museum on the Bowery had its machines removed by detectives. An arcade on Eighth Avenue had its wares confiscated and its manager locked up during the dragnet operation. Two shows in the Tenderloin district were raided. “The exhibitors are running for cover,” cried Hearst’s paper. Gallery doors were padlocked. Windows whitewashed. Sensational photo displays taken down. Barkers and idle crowds replaced by signs reading “Closed for Repairs.”

But the battle was not over. The contagion had spread from the depths of the Bowery uptown to Broadway. The enterprising Journal reporter took it upon himself to follow “a batch of high-school girls up Broadway,” near West 13th Street. He surmised they were walking home from school because they were using their nickel streetcar fares for picture gazing. The girls congregated around the “worst pictures.” “By pooling their pennies,” he said, “the whole crowd managed to see every questionable picture on view.” Each machine in the Broadway parlor was marked with a salacious phrase: “This is a Hot One!” “Don’t Miss This.” “Not meant for church folk.” “This is very warm.” Compounding the atmosphere of vice, the exposé warned, these places had backrooms that featured not leg shows, but gambling outfits.

The word-picture sketched here is strikingly reminiscent of Fun, One Cent (1905), an etching by the Ashcan School artist John Sloan for his “New York City Life” series (figure 3). Young women and adolescent girls, a mix of working-class and middle-class teens “slumming” (as Sloan himself often did), respond to naughty penny-in-the-slot mutoscope scenes. Like the schoolgirls described in the New York Journal, they pool their pennies, crowding together for a shared peek. “Girls in their Night Gowns—Spicy,” “Those Naughty Chorus Girls—Rich, 1¢,” “How She Did…,” “Trying on Her Stocking,” “Why She Didn’t Scratch,” “… But He Did,” read the signs above the peep shows. The youngest two are short enough to require a stool to see into the mutoscopes (a stool the arcade apparently has on hand for its smaller habitués). Another girl wears a look of mild shock, while three others peer into eyepieces. A predominant tone of amusement, however, is created by the broad smile worn by a laughing woman at the center of the image. She watches not the naughty peep-show but the face of her shocked companion. She appears to be an experienced older viewer introducing schoolgirls to the arcade. Sloan’s representation is not one of panic or indignation, but of almost-quaint celebration, relating a pedestrian pleasure gleaned from an entertainment that is only mildly risqué. Fun for a penny is, if not altogether harmless, part of everyday urban life.[4]

Figure 3

Fun, One Cent, John Sloan, 1905

This suggested reception of the moving-picture arcades of 1899 found no place in the Hearst reporting. With the movie menace making its way uptown, the Journal marshaled an array of civic forces to endorse the police campaign the paper claimed to have led. Letters of support from the usual suspects—the YMCA, WCTU, Salvation Army and local school board—were run in a box beneath a conspicuous editorial cartoon: “Gathering the Harvest of Indecency!” exclaimed the caption. Documents such as this, and a second cartoon the following day, “Journal’s Searchlight Closes Dives” (figure 4), make the brand of journalism pioneered by Hearst papers worth mining as responses to early motion pictures. The first drawing vividly encapsulates the exhibitor/audience relationship, showing it as a shameful act of child exploitation. A corpulent, gauchely-attired merchant sits on a stool, idly raking in the coins that fall into his top hat courtesy of a moving-picture machine. Four middle-class school children—two older girls, two boy tots—look toward the viewing cabinet. Again the content of the “moving pictures” is not specified, but merely assumed to be the essence of indecency. As the second cartoon also demonstrates, the offending pictures could not be shown or even represented. Like most moralist renderings of pornography, they could only be imagined as something too graphic to graph.

Figure 4

New York Evening Journal, December 1, 1899

What these drawings do cast in material terms are the proprietors under attack. As is common in other editorial depictions from this period, at least in Hearst papers, the child of the city is the victim of economic exploitation by immoral capitalists. To be sure, this picture merchant—with his checkered vest and striped pants—is of a petty class, not a robber baron or greedy trust operator. For the early cinema historian, the images also suggest that these moving-picture machines—which are only generically referred to by the reporter—were mutoscopes, rather than Edison kinetoscopes or some other brand of early motion-picture technology. Although the newspaper caricatures lack some details (such as the mutoscope’s scalloped cabinet), the hand-cranked operation is a clear marker of American Mutoscope and Biograph design. The coin slot is another. The Journal reports frequently refer to the nickel or “penny-in-the-slot machines” plaguing New York. Simultaneously ads for American Mutoscope and Biograph Company’s coin-in-the-slot machines could be found in the New York Clipper and other trade papers. Sloan’s Fun, One Cent accurately details both the machine’s clamshell exterior and its written instructions: “Drop One Cent in the Slot. Turn Handle to Right.”[5] Furthermore, Biograph was identified with the genre of burlesque films showing women disrobing, which it produced for mutoscope exhibition.

By 1899, the novelty period for the Edison’s kinetoscope had passed, with projected film shows having been in operation for four years. Biograph, however, was at the peak of production for its mutoscope customers. In 1898, Herman Casler, cofounder of American Mutoscope, made improvements to the patented viewing device, allowing the company to launch what Charles Musser (1990, p. 263) calls “a network of mutoscope parlors,” starting on Broadway in New York.[6] Within a year, American Mutoscope and Biograph was producing hundreds of subjects, including flip-card versions of some longer films, such as its two-hour recording of the Jeffries-Sharkey Fight filmed at Coney Island in November 1899. But for the arcade market, the company concentrated on voyeuristic, single-shot movies, most featuring scenes of women in some state of undress. In 1899 alone, AMB copyrighted at least thirty such titles (The Way French Bathing Girls Bathe, The Corset Model, Phillis Was Not Dressed to Receive Callers, etc.) and produced far more. Its sister Mutoscope companies in France, Britain and elsewhere were issuing similar work.[7]

Why, then, did the Hearst press not attack the producers of the immoral pictures and the manufacturers of the machinery that put indecent material before the eyes of so many Bowery boys and girls? Many news accounts of motion pictures published in the 1890s allude to trade names for the current film technologies—kinetoscopes, cinématographes, biographs, veriscopes, cineographs and so on. Hearst’s Journal and his flagship San Francisco Examiner had been doing so for five years, even publishing “kinetoscopic” cartoon strips on occasion. Yet this week-long parade of articles never refers to the galleries as containing anything other than “moving-picture machines.”

At least two explanations for letting Biograph and other manufacturers off the hook are plausible. First, the Journal could hardly engage in a campaign against Biograph, since it had been publishing illustrations based on American Mutoscope and Biograph’s films throughout November 1899. Frames from the Jeffries-Sharkey Fight were used in the extensive coverage of the bout in Hearst’s sports pages and clearly credited the company by name as the copyright holder of the images. Earlier, the American Mutoscope Company had produced a motion picture entitled New York Journal’s War Issue (1898), showing Journal employees aboard a ship off the coast of Cuba, where they prepared issues for Spanish-American War soldiers on shore.[8] Second, Hearst papers had been using cinematic and other screen technologies for their own promotional purposes. Though the Journal could be a critic of the commercial exploitation of children, its owner and editors were nonetheless in league with other nascent media industries. As a matter of sensational copy, it was far easier to attack a marginal class of lowlife merchants than to take on Thomas Edison or even Biograph.

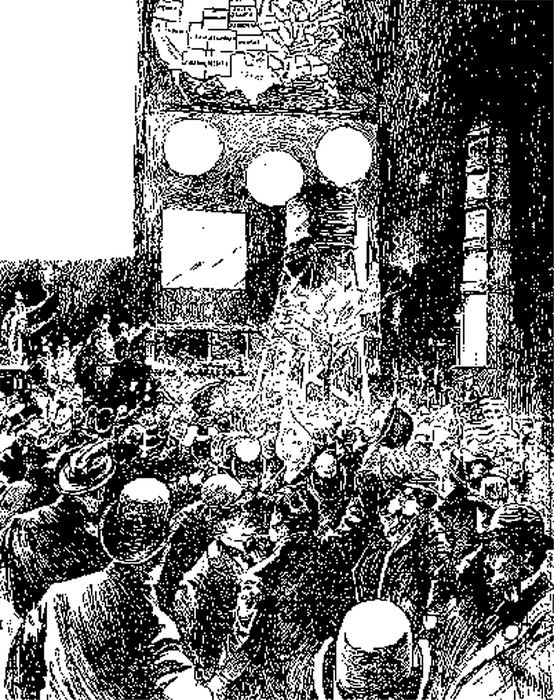

The Hearst company’s use of early screen technology is worth noting. Like other big city newspapers, including Hearst’s first daily, the San Francisco Examiner, the New York Evening Journal promoted itself and purveyed its news with highly visible bulletin services. For events of immediate topicality—elections, sporting events, war reports—newspaper offices attracted huge crowds eager to hear results. Telegraph and telephone operators with megaphones became supplemented with visual and aural elaborations. Hearst added motion-picture displays to his bulletin services as early as 1896. Notably, the New York Evening Journal used a spectacular display of electric technologies to increase its public profile in a city with a highly competitive newspaper market. Hearst purchased the small Morning Journal at the end of 1895 with designs to challenge Joseph Pulitzer’s World with the tabloid style that had gotten high circulation in California. In addition to his well-known tactics—hiring competing columnists, luring Outcault and his “Yellow Kid” comic strip from the World, using splashy headlines and illustrations—the publisher put his news on the street with large screen devices.

The U.S. presidential election of 1896 was the launching point for the Journal’s skyrocketing sales. Readers were told “there will be stereopticon-kinetoscope exhibitions, and some startling new inventions” helping to deliver electoral results. The bulletin service became part of the detailed reportage of the spectacle (figure 5). At several locations throughout Manhattan, including the Journal headquarters, wooden towers were erected which held stereopticons and other projection devices. A large canvas screen (“monster bulletin board”) was hung on the side of the Journal building. A map of the United States was placed at the top, illuminated with two colors of lights. The spaces below it were filled with a combination of text (headlines), still images, and, apparently, movies, designed to “amuse” the throngs until the election results were known. The paper noted that the service “threw on cartoons and pictures more or less moving,” including “panoramascope” pictures. “At Hammerstein’s Olympia” theater, where an additional news station was installed, it claimed: “the cinegraphoscope, that new extraordinary combination of electricity and photography, seemed to make the canvas alive with moving figures.”

Figure 5

New York Evening Journal, November 4, 1896. Hearst’s “monster bulletin board” hung on the side of the Journal building, delivering news on election night: “stereopticon-kinetoscope exhibitions, and some startling new inventions … threw on cartoons and pictures more or less moving.”

More stunning than the movies perhaps, were hot-air balloons that flew above Manhattan and New Jersey, rigged with electrical stars that illuminated green when William McKinley and Republicans won, red for Hearst’s Democrats. In a triumphant display of technology and public spirit, brass bands played the “Star-Spangled Banner” when the bulletin proclaiming “McKinley Is Elected” shone on the screens of New York. The projecting and screen technologies of bulletin services became a fixture of turn-of-the-century public news events. (Hearst, incidentally, got his candy. The Journal’s circulation became the greatest in New York, selling over a million penny editions on election night 1896.) This then was the press incorporation of protocinematic technologies into discourses about the public sphere. The newspaper deployed them towards the virtues of journalistic enlightenment, democratic process and public participation in electoral politics. Technology in the service of nation building was the lauded application.

The New York Journal, therefore, knew well the world of the screen. In choosing to demonize cheap mutoscope arcades it was painting itself as a policing force against the immoral excesses of Barnum capitalism, a virtuous public organ that knew its proper role in the body politic. By December 1, 1899, the paper was wrapping up its manufactured picture panic. (“Manufactured” because no other newspapers I have read mention the phenomenon.) It promised “to seek the arrest, indictment, trial and conviction of those responsible for” immoral pictures. On day three of the crusade, a new list of violators appeared: a “Cosmorama Company” and the “Electric Moving Picture Concern” on Broadway. Outfits with generic names—The Fair, Penny Arcade, the Moving Picture Company—were said to be taunting the police with their defiance of the law.

The Journal’s unlikely hero in this crusade was New York’s notoriously corrupt chief of police, William S. Devery (himself the subject of Biograph films in 1898 and 1899).[9] Having recently been returned to office by Tammany Hall (after a criminal conviction), Devery played the patronage game well. He also kept his policing hand in the world of public amusements—brokering prizefights, co-owning the New York Yankees baseball team in 1903. Devery lent his name to the blitz against “the harvest of indecency.” His endorsement, ordering the confiscation of “all machines that exhibit immoral pictures,” stood directly beneath the cartoon. The following day the paper quoted the chief as telling his troops to “make a record of every hole and corner” in the city that housed moving-picture devices.

The Journal declared victory. The school superintendent had promised written guidelines for every teacher to warn students about the picture danger. Inspected machines had all been shut down or were showing clean pictures. Police had hauled in proprietors and their devices. The headlines boasted: “Evening Journal Wins for Decency,” “Congratulations from Those Who Aided in the Evening Journal’s Crusade,” “Evening Journal Wins After Quickest Crusade on Record,” “Traction Trust Exposed.” The cartoon—“Journal’s Searchlight Closes Dives”—was the concluding narrative image. While the newspaper takes full credit for shining a light on the dark corners of the amusement world, the flashlight labeled Journal is marked as in the hand of the police.

Public actions and reactions like these did not curtail production of salacious films. Instead, as Robert C. Allen and others have written, an “important subindustry” in “sexualized spectacle” continued at American Mutoscope and Biograph, with active (albeit “subterranean”) production of flip-card movies continuing through at least 1908. The exhibition of such material took an increasingly marginalized form. Mutoscope machinery remained in service at amusement parks “through the 1920s,” Allen notes (1991, p. 265). But in addition to these quaint nostalgia items, more explicit mutoscope displays persisted much longer in even more highly marginalized venues. Into the 1940s, children were still sneaking peeks in arcade settings, both urban and rural.

The FSA Photographs of Children at the Movies, 1938

The change in American attitudes about “Motion Pictures and Youth” (as the 1934 Payne Fund studies termed it) is well illustrated by the visual records produced by Roy Stryker’s photographic unit of the Farm Security Administration between 1935 and 1942.[10] Like the yellow press, this well-known collection has been a neglected primary source for cinema historiography. Near the height of America’s moviegoing age, the nation’s best documentary photographers captured images of people gathering in front of movie houses. Stryker in fact prescribed the subject in his written instructions for photodocumentation.[11] In these theater “front views,” young moviegoers often predominate. So much so that a subgenre emerges, one which might take the name that photographer Russell Lee gave to his 1939 series snapped in Alpine, Texas: “Children in front of movie theatre.” Lee shot this subject more often than his colleagues, but similar scenes appear throughout FSA photographs by Ben Shahn, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein and others. Collectively, the photographs depict the cinema as a cherished public space, accommodating children with shelter from the storm during the Depression.

The content and tone of these candid shots contrast with the alarmism of the 1899 drawings of mutoscope-made children. The movie house has become both a place of childhood desire and community stability. Kids are shot outside of theaters, typically gazing at posters and lobby cards. Most are wide shots of school-age youths congregating in front of theaters. They stand in safe, bright, clean environs, a contrast to the images of poverty associated with other FSA documents. The movies they wait to see are wholesome, Hays-approved entertainment, often kiddy matinee fare: B westerns, Laurel and Hardy comedies, serials. As Gomery and others have shown, throughout the 1930s, theater owners and Hollywood distributors systematically programmed children’s matinees with age-appropriate but cheap double features.[12] The FSA’s documentation, then, corroborates the success of the motion picture industry and civic groups in implementing exhibition controls on young moviegoers.

The consistency of the genre makes Lee’s “Boys Looking at Penny Movies” all the more exceptional. Amid the normative pictures of children as matinee spectators appears this dark “remake” of Sloan’s 1905 etching. Three boys stand before a peep-show machine at the state fair in Donaldsonville, Louisiana, October 1938. The youngest two lean in to the eyepiece together, one placing his arm familiarly around his companion—a gesture identical to that seen in Fun, One Cent. Also like Sloan’s drawing, Lee’s photograph features a compositionally dominant (and older) figure standing to the left. However this teenager offers not a laugh but a guilty return glance, which is frozen in the camera’s Weegee-like flash. The boys are caught in a transgressive act. Lee’s framing makes their crime clear. They have spent their penny to see Wiggling Wonders, a movie advertised by an explicit picture of two naked women. The boys ignore the machine advertising “Charlie Chaplin in The Dumb Waiter,” presumably the innocent choice, a children’s favorite of yesteryear.

A close examination of the photograph confirms that the Depression-era fairground remained a home for mutoscope machines nearly identical to those sold to New York picture galleries in 1899. The Mutoscope brand name, coin slot, and cranking instructions are embossed on the devices, although the movies are not turn-of-the-century Biograph. The parent company ceased production of its arcade machinery and peep-show pictures in 1909, the year in which AMB joined forces with the Motion Picture Patents Company. However, the arcade market continued to offer hand-cranked movie viewers. In 1923, William Rabkin bought the rights to Mutoscope from Biograph. His International Mutoscope Reel Company manufactured compact, steel versions of the mutoscope (along with other arcade devices) from 1926 through the end of the 1940s. According to Bob Klepner, from 1923 to 1928 Rabkin also shot new moving pictures for the mutoscope format. Filmed in New York, these included Wiggling Wonders (1928), one of Rabkin’s last productions. (It was also apparently one of his most popular, its marquee poster showing up in other period photographs of arcades and in surviving machines as faraway as Australia.) Alongside these original nudie novelties, he also issued mutoscope-formatted versions of silent-era works licensed from Hollywood companies, including Warner Bros., Keystone, Mutual, and Universal.[13] For a two-reel film such as The Dumb Waiter (1916, Mutual), which was not made for peep shows, Rabkin would have converted one or two-minute excerpts into a flip-card show, making a quaint, bowdlerized artifact of early cinema.

While the mutoscopes in Lee’s photo were certainly from International Mutoscope, Rabkin was not alone in providing content for this market. Other producers continued to make such films long after Wiggling Wonders. As Eric Schaefer documents in his brilliant history of exploitation cinema, such short films of stripteases and nude women were shot on 16mm, then sold to the home and arcade markets into the 1940s. Just a month before Lee recorded this Louisiana fairground scene, the Motion Picture Herald noted: “Mutoscope parlors linger still in the poor quarters of many of the larger cities.”[14] Thus, the peep-show arcade’s association with both children’s amusement and the temptation of stag pictures persisted for decades.

However, the less than reputable spaces surrounding the mutoscope remained quite apart from the well-policed Main Street moviehouse. The photographs Lee shot on this Louisiana fairground trip make this clear. His only other pictures of the penny movies feature undistracted voyeurs. One shows a lone, middle-aged white man with his face pressed against the Wiggling Wonders viewer. The second features three young black men trying to peer into a single mutoscope.[15] The other attractions include fortune tellers, a glass eater, arcade gadgetry, barkers hawking games of chance, and a circus geek biting the head off of a snake—the things that made the fairground notorious. While Lee’s images demonstrate that there were less sordid things one could do with a penny at a Louisiana fair (get it engraved with the Lord’s Prayer—for five cents), his representation of boys sneaking peeks at dirty pictures stands in stark contrast to his celebratory depictions of innocents at the matinee movie show. By 1938, motion-picture theaters were part of “normal life.” Concerns about immoral film content and adverse effects on children never went away, of course, but those deemed truly dangerous had been driven to the margins.

Another FSA image of boys watching mutoscope pictures, from September 1938, confirms this. Taken in Granville, West Virginia, Marion Post Wolcott’s photograph bears the caption: “‘It’s a dirty jip,’ say the mine workers’ sons in the penny arcade at outdoor carnival” (figure 6). As in Russell Lee’s photo, boys pool pennies to look at movies, lured by stills of nude women and teasing titles: Ain’t She Sweet, Whimsical Lady, Strip Poker. As in Lee’s photo, the patrons are working-class boys, rural and small-town fairgoers encountering these stag movies at an annual fairground event. However, Wolcott’s caption indicates quite a different form of reception. The boys proclaim the mutoscope attraction a fraud, presumably for not delivering the thrill promised by its external display. Indeed Wolcott’s other images of this West Virginia carnival indicate that competition for thrill-seekers’ attention was steep. Thirty seconds of peering at a miniature screen must have paled next to the Ripley’s Believe-It-or-Not freak exhibition and the sideshow with hermaphrodites on display.

Figure 6

Marion Post Wolcott’s “It's a dirty jip,” say the mine workers’ sons in the penny arcade at outdoor carnival. Granville, West Virginia, September 1938.

Conclusion

“So simple,” said the New York Herald of the mutoscope in 1897, “that a child can operate it.”[16] And many did. In some instances, arcades accommodated the child-sized viewer with eyepieces lowered or stepping stools provided. While the Hearst exposés of 1899 did not mention this, a prosecutor in 1904 made an obscenity case against an Australian mutoscope exhibitor, asserting: “The worst feature of the place was that to enable children to look at the pictures a small platform for them to stand on had been built in front of the machines.”[17] The International Mutoscope machines seen in Russell Lee’s pictures are modified versions of the taller pedestal-mounted units common at the turn of the century. They are placed on simple tables, low enough for young boys to lean comfortably into the viewer; so low that adults must bend down to see the wiggling wonders. As penny-ante operations, the rural-fairground and city-arcade mutoscopes were able to exploit a fringe, largely unadvertised movie market, one that indiscriminately took in coins from adults and children. So much had the public perception of moviegoing changed since the advent of moving pictures that even the fairly explicit nudity available to kids on the peep-show market continued without significant comment. As an episode for comparative media studies, the 1899 newspaper campaign against moving-picture machines is less connected to 1938’s mutoscope/child exploitation during the golden age of moviegoing than it is to the 1990s’ media scare about children and the Internet. Hearst’s attack on slot-machine pictures gathering the harvest of indecency may have been short-lived and self-interested, but it is no less instructive for the way it demonstrates how uniform the public discourse about new media and vulnerable viewers remained over the course of the twentieth century.

Appendices

Note sur le collaborateur

Dan Streible

Il est professeur en études cinématographiques à University of South Carolina, où il organise le Orphan Film Symposium. Il a publié plusieurs articles sur le cinéma des premiers temps. Il est actuellement l’un des responsables de la publication de The Moving Image : Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists et il a rédigé l’article « Film and Media Preservation » du prochain Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. Son livre Fight Pictures : A History of Boxing and Early Cinema (Smithsonian Institution Press) paraîtra prochainement.

Notes

-

[1]

See also Bob Klepner, “The Mutoscope in Australia,” unpublished ms. for Coin Drop International; Klepner and Long 1996 (pp. 34-37 and pp. 54-55). Klepner has an extensive private collection of films, machinery, papers and ephemera. I thank him for sharing his knowledge. Personal correspondence, January 7 and February 23, 2003.

-

[2]

All material cited is from these 1899 New York Journal items: “Picture Dives Close in Panic,” Nov. 28, pp. 1, 9; “Picture Galleries of Hell,” Nov. 28, p. 9; “2 Arrests in Slot Machine Crusade,” Nov. 29, pp. 1-5; “Moral Forces Close Picture Dives,” Nov. 29, p. 5; “Gathering the Harvest of Indecency,” Nov. 29, p. 5; “Devery Fights the Slot Dives,” Nov. 30, p. 5; “Evening Journal Wins for Decency,” Dec. 1, p. 4; “Journal’s Searchlight Closes Dives,” Dec. 1; “Evening Journal Wins After Quickest Crusade on Record,” Dec. 1; “Slot Machines Seized by Police,” Dec. 2, p. 1. For background on Hearst, see: Carlson 1937; Everett Littlefield 1980; Nasaw 2000; Procter 1998; Swanberg 1967.

-

[3]

British newspapers provided more specific descriptions of objectionable material. A letter from a member of parliament, for example, ran in The Times of London, August 3, 1899, with MP Samuel Smith complaining of the “corruption of the young that comes from exhibiting under a strong light, nude female figures represented as living and moving, going into and out of baths, sitting as artists’ models etc.” (cited in Bottomore 1996, p. 14.)

-

[4]

During a group discussion of Fun, One Cent at the 2002 Domitor conference, Tom Gunning suggested that Sloan was representing the central woman in the picture as a prostitute—thus offering a far less innocent picture of mutoscope viewing and heightening the irony of Sloan’s “Fun” title. If the coding of her as a prostitute derives from her costuming, then this seems ambiguous at best. The plumed hat she wears was a common fashion of the time. In-depth analyses of the etching do not mention such an interpretation. Even Suzanne L. Kinser’s does not include Fun, One Cent in its discussion (see Kinser 1984). See also Weintraub 2001; Zurier 1995; McDonnell 2002.

-

[5]

Film historian Janet Staiger mistakenly refers to Fun, One Cent as depicting “movie kinetoscopes,” in Bad Women: Regulating Sexuality in Early American Cinema (Staiger 1995, p. 8). Art historian Patricia McDonnell (2002, p. 21) does likewise in misdescribing kinetoscopes as “hand-crank peep shows.” Also worth noting: the New York Clipper ads of 1899 featured a photograph of a woman looking into a clamshell mutoscope (which is listed as 4 feet 8 inches high). Although not identified in print, the woman was Anna Held, among the most popular stars of the musical stage. Brought to New York from Europe by Florenz Ziegfeld, Held was a petite, coquettish performer noted for her suggestive songs (“I Just Can’t Make My Eyes Behave,” “Won’t You Come and Play with Me?”). As such, she matched the mutoscope’s image as both naughty and socially acceptable. In 1901, Biograph shot two mutoscope scenes of her sipping champagne (Anna Held, I and II). See Golden 2000 (p. 50).

-

[6]

Klepner credits Casler with the technical improvements that led to the rapid spread of mutoscope displays in 1898.

-

[7]

The following titles were copyrighted by American Mutoscope and Biograph in 1899: A Burlesque Queen, Chorus Girls and the Devil, The Corset Model, The Dairy Maid’s Revenge, Fougère, Four A.M. at the French Ball, Her First Cigarette, Her Morning Dip,An Intrigue in the Harem, The Jealous Model, Just Cause for a Divorce, A Lark at the French Ball, Living Pictures [A French Model], Love in a Hammock, A Midnight Fantasy, Phillis Was Not Dressed to Receive Callers, The Poster Girls, The Poster Girls and the Hypnotist, The Price of a Kiss, A Scandalous Proceeding, The Soubrette’s Birthday, The Summer Girl, The Sweet Girl Graduate, Two Girls in a Hammock, An Up-to-Date Female Drummer, The Way French Bathing Girls Bathe, What Hypnotism Can Do, When Their Love Grew Cold, Wonderful Dancing Girls, The X-Ray Mirror. Far fewer such titles had been made for the mutoscope market prior to 1899 (e.g., A Dressing Room Scene, 1897; How Bridget Served the Salad Undressed, 1898). Most earlier subjects were comparatively tame, nonnarrative dance scenes, such as Skirt Dance by Annabelle (1896), Little Egypt (1897), although, as Musser (1990, pp. 187-188) documents, mutoscope pictures What the Girls Did with Willie’s Hat (1897) and Fun in a Boarding House (1897) drew objections when shown at Coney Island.

-

[8]

AMB Picture Catalogue (Nov. 1902).

-

[9]

The 1902 catalogue lists Chief Devery at Head of N.Y. Police Parade (American Mutoscope Company, June 1898) and Chief Devery and Staff (AMB, 1899), taken during a Memorial Day parade. See also New York Police Parade, June 1st, 1899 (Edison).

-

[10]

Several thousand photographs are available on the Library of Congress’s website, “America from the Great Depression to World War II: Black-and-White Photographs from the FSA-OWI, 1935-1945,” <lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/fsahtml>.

The Farm Security Administration was originally part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The FSA and its predecessor, the Resettlement Administration, were programs designed to assist poor farmers. Roy Emerson Stryker supervised photography in the FSA/RA’s “Historic Section” from 1935 to 1942. His staff created 77,000 black-and-white photographs that became synonymous with Depression iconography. In 1942, the FSA was put under the Office of War Information. See Stryker and Wood 1973; Plattner 1983; Hurley 1978.

-

[11]

Stryker, “The Small Town: A check outline for photo-documentation” (n.d.), Item III, “Theaters” instructs photographers to look for “Front view—details of ticket booths, displays, person selling tickets—note signs in ticket booths (box office). Groups buying tickets, looking at displays,” in Kinder Carr 1980 (pp. 92-93).

-

[12]

See Gomery 1992 (pp. 138-139).

-

[13]

Klepner identifies Wiggling Wonders as one of the last Rabkin productions (#7608). His collection includes an original International Mutoscope marquee poster for the movie, as well as an undated photograph showing a young boy, dressed in a Scout uniform, peering into a clamshell mutoscope advertising Wiggling Wonders—alongside teasers Red Hot Mamma and Baby Face, as well as a Hollywood title, Jack Hoxie in the western The Fighting Three (1927, Universal). In both Wiggling items, the words “Real Moving Pictures!” have been added to the marquee seen in Russell Lee’s 1938 photographs. Other data about International Mutoscope from these collectors’ websites: Wayne Namerow, “The Penny Arcade Website,” 2003, <pinballhistory.com>; “International Arcade Museum,” 2002, <coin.klov.com>; and Mutoscope Manufacturers Extraordinaire, “Mutoscope Manufacturers,” Sheffield, UK, n.d., <www.mutoscope.co.uk>. (All accessed Feb. 1, 2003.)

-

[14]

Motion Picture Herald, Sept. 24, 1938, p. 56, cited in Schaefer 1999 (p. 216 and p. 306).

-

[15]

Russell Lee’s photographs are catalogued as: “Man looking through penny peep show, state fair, Donaldsonville, Louisiana,” (Nov. 1938), LC-USF33- 011752-M1, and [Untitled], LC-USF34- 031680-D. The latter appears to show the same fairground arcade seen in “Boys Looking at Penny Movies,” but details are less clear. The faces of the three African-American spectators are not visible, however their clothing and taller heights indicate they are probably adults or older teens. The lone mutoscope placard is not legible, although it does not resemble the signs for Wiggling Wonders or the Chaplin film seen in Lee’s other Donaldsonville photos.

-

[16]

“Another Scope,” New York Herald, Feb. 7, 1897, p. 9D, cited in Musser 1990 (p. 176).

-

[17]

Mr. Duffy K.C., prosecuting Mutoscope Company Manager, Fredrick G. Wilson, for exhibiting four “obscene” titles for profit: Why Marie Blew Out the Light (1898, British Mutoscope), The Temptation of St. Anthony (AMB, 1900), A Peeping Tom (American Mutoscope Co., 1897), and Behind the Scenes (Gaumont[?], 1904). Klepner, citing Melbourne Argus, Mar. 12, 1904.

Bibliographical References

- Allen 1991: Robert C. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Bottomore 1996: Stephen Bottomore, “The Coming of the Cinema,” History Today, no. 46, 1996.

- Brown and Anthony 1995: Richard Brown and Barry Anthony, History of the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company: A Victorian Enterprise, Trowbridge, Flicks, 1995.

- Carlson 1937: Oliver Carlson, Brisbane: A Candid Biography, New York, Stackpole Sons, 1937.

- Everett Littlefield 1980: Roy Everett Littlefield, William Randolph Hearst: His Role in American Progressivism, Lanham, University Press of America, 1980.

- Golden 2000: Eve Golden, Anna Held and the Birth of Ziegfeld’s Broadway, Lexington, University of Kentucky Press, 2000.

- Gomery 1992: Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

- Hansen 1993: Miriam Hansen, “Early Cinema, Late Cinema: Permutations of the Public Sphere,” Screen, Vol. 34, no. 3, 1993, pp. 197-210.

- Hurley 1978: F. Jack Hurley, Russell Lee, Photographer, New York, Morgan & Morgan, 1978.

- Kinder Carr 1980: Carolyn Kinder Carr (ed.), Ohio: A Photographic Portrait, 1935-1941; Farm Security Administration Photographs, Kent, Kent State University Press, 1980.

- Kinser 1984: Suzanne L. Kinser, “Prostitutes in the Art of John Sloan,” Prospects, no. 9, 1984, pp. 231–254.

- Klepner and Long 1996: Bob Klepner and Chris Long, Cinema Papers, no. 109, 1996.

- McDonnell 2002: Patricia McDonnell (ed.), On the Edge of Your Seat: Popular Theater and Film in Early Twentieth-Century American Art, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2002.

- Musser 1990: Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema, New York, Scribner, 1990.

- Nasaw 2000: David Nasaw, The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst, Boston, Houghton-Mifflin, 2000.

- Plattner 1983: Steven W. Plattner, Roy Stryker: U.S.A., 1943-1950, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1983.

- Procter 1998: Ben Procter, William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863-1910, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Schaefer 1999: Eric Schaefer, Bold! Daring! Shocking! True! A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959, Durham, Duke University Press, 1999.

- Staiger 1995: Janet Staiger, Bad Women: Regulating Sexuality in Early American Cinema, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

- Stryker and Wood 1973: Roy Stryker and Nancy Wood (eds.), In This Proud Land: America 1935-1943 as Seen in the FSA Photographs, Greenwich, New York Graphic Society, 1973.

- Swanberg 1967: W. A. Swanberg, Citizen Hearst: A Biography of William Randolph Hearst, New York, Scribner, 1967.

- Weintraub 2001: Laural Weintraub, “Women as Urban Spectators in John Sloan’s Early Work,” American Art, Vol. 15, no. 2, 2001, pp. 72-83.

- Zurier 1995: Rebecca Zurier (ed.), Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and Their New York, National Museum of American Art, 1995.

List of figures

Figure 1

New York Evening Journal, November 29, 1899

Figure 2

Russell Lee’s Boys looking at penny movies at South Louisiana State Fair. Donaldsonville, Louisiana, October 1938.

Figure 3

Fun, One Cent, John Sloan, 1905

Figure 4

New York Evening Journal, December 1, 1899

Figure 5

New York Evening Journal, November 4, 1896. Hearst’s “monster bulletin board” hung on the side of the Journal building, delivering news on election night: “stereopticon-kinetoscope exhibitions, and some startling new inventions … threw on cartoons and pictures more or less moving.”

Figure 6

Marion Post Wolcott’s “It's a dirty jip,” say the mine workers’ sons in the penny arcade at outdoor carnival. Granville, West Virginia, September 1938.