Abstracts

Abstract

Despite Canada’s success in attracting international students to its postsecondary campuses, it sends very few domestic students abroad, and especially so from its college sector. This paper offers a brief overview of Canada’s policy approach to study abroad, literature review on students’ participation in study abroad, and outcomes of a study on students’ (perceived) barriers at a college in Ontario, Canada. Students at the college were surveyed to examine their attitudes towards study abroad participation and their perceived barriers regarding study abroad. The study found that students were overwhelmingly interested in study abroad but perceived strong barriers to participation, findings which are consistent with the literature: financial, academic, social/familial barriers, and accessibility, safety, and support concerns. These findings suggest that through expansion of national programming, coordination of provincial strategy, and inclusive, accessible policies and programming at the institutional level, more college students will be able to receive the many documented benefits of study abroad experiences.

Keywords:

- study abroad,

- college students,

- academic mobility,

- Canadian higher education

Résumé

Bien que le Canada réussisse à attirer des étudiants étrangers sur ses campus postsecondaires, il envoie très peu d’étudiants nationaux à l’étranger, en particulier dans son secteur collégial. Ce document présente un bref aperçu de l’approche politique du Canada en matière d’études à l’étranger, une revue de la littérature sur la participation des étudiants aux études à l’étranger et les résultats d’une étude sur les obstacles (perçus) par les étudiants d’un collège en Ontario, au Canada. Les étudiants de ce collège ont participé à un sondage sur leurs attitudes au sujet de la participation aux études à l’étranger et les obstacles qu’ils perçoivent à cet égard. L’étude a révélé qu’une majorité considérable d’étudiants étaient très intéressés par les études à l’étranger, mais qu’ils percevaient des obstacles importants à leur participation, ce qui conforme à la littérature : soucis financiers, académiques, sociaux/familiaux et ennui d’accessibilité, de sécurité et de soutien. Ces résultats suggèrent que grâce à l’expansion des programmes nationaux, à la coordination des stratégies provinciales et à des politiques et programmes inclusifs et accessibles au niveau institutionnel, un plus grand nombre d’étudiants pourront bénéficier des nombreux avantages attestés des expériences d’études à l’étranger.

Mots-clés :

- études à l’étranger,

- étudiants d’enseignement supérieur,

- mobilité académique,

- enseignement supérieur canadien

Article body

Introduction

Study abroad programs[1] often reflect postsecondary educational institutions’ efforts to internationalize campuses and offer students opportunities to engage with diverse global communities, develop intercultural competencies, and enhance global citizenship. They have the potential of transforming education by generating new learning and pedagogical trajectories, research, and partnerships.

Despite Canada’s popularity as a destination for international education, Canadian students have not shown large participation in outbound mobility or study abroad experiences. Over the course of a degree program, about 11% of Canadian undergraduate students engage in a study abroad experience (Universities Canada, 2022a; Global Affairs Canada [GAC], 2019). This is noticeably fewer than students from linguistically, culturally, and economically comparable countries such as Australia (19%) and the United States (16%). In the European Union, it is reported that about 43% of undergraduate students travel abroad each year through flagship programs such as Erasmus+[2] (Eurostat, 2022).

When examining the number of students engaged in study abroad programs in Canada, it is evident that university students have higher representation than college students[3]. In an academic year, about 3% of university students study abroad compared to only 1% of college students[4] (Canadian Bureau of International Education [CBIE], 2022). Colleges have distinct functions from universities. They have a much greater focus on the labour market, offering many applied credentials and facilitating workplace connections through internships and co-op experiences. Furthermore, their programs are often shorter (e.g., diplomas) and more condensed. This context offers unique affordances and limitations when it comes to study abroad.

While there are many studies that examine Canadian university students’ attitudes, perceived values and barriers, and experiences with study abroad, few studies examined college student experience in the province of Ontario (Algonquin College, 2021). Despite Ontario having 196,257 students enrolled (as of 2021) in the public college system (Ontario Colleges Library Service, 2023), there is limited understanding of the rationales of Ontario college students’ engagement in study abroad, their (perceived) barriers and preferred modalities. Hence, this study focuses on an Ontario college with the goal of examining the following questions:

-

What are the students’ attitudes to and perceived value of study abroad?

-

What are their (perceived) barriers to participation in study abroad programs?

-

What are their preferred modalities, duration, and destinations of study abroad programs?

Understanding the unique experiences and barriers of these college students will help with developing more inclusive study abroad experiences at the institutional level and contribute needed data on the college sector in Ontario. Furthermore, as the Government of Canada identified study abroad as a priority in its International Education Strategy 2019–2024, investing millions of dollars to support inclusive and accessible programming at postsecondary institutions, this knowledge will inform the development of nation-wide programs that can effectively serve the unique circumstances of the college student experience.

National and Provincial Study Abroad Policies in the Canadian Context

Scholars argued that whereas Canada has been very successful at international student recruitment, it falls behind in terms of sending domestic students abroad, warning that Canadian students are “homebodies” and “insular” (e.g., Barbarič, 2018; CBIE, 2016; El Masri, 2019; Popovic, 2013). Canada was notably absent from a large surge in outbound student mobility that occurred between 2005–2017 due to various and contradictory conceptions of study abroad being espoused by competing federal and provincial jurisdictions (Barbarič, 2020; El Masri, 2019). In 2013, Canada was the sole G7 country without a strategy to increase outward student mobility for its postsecondary education students (Barbarič, 2017; 2020).

While education remains a provincial jurisdiction, the federal government’s engagement with international education was facilitated due to its constitutional responsibilities for economic development and foreign affairs (Trilokekar & El Masri, 2016; 2017). The federal government released Canada’s first International Education Strategy: Harnessing Our Knowledge Advantage to Drive Innovation and Prosperity in 2014. While the focus of the Strategy was international student recruitment and retention, there was a shy nod to increasing the number of Canadian students abroad. However, it failed to set targets, measures, or funding towards achieving this goal (Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, 2014). Recognizing that Canada lagged behind its Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) peers and in response to warnings that Canada was not preparing its students to meet the rapidly changing world (Barbarič, 2020; Biggs & Paris, 2017), in the second iteration of Canada’s International Education Strategy 2019–2024, the federal government identified outward student mobility as one of its three key objectives, setting targets and allocating funds of up to $95 million. Employment and Social Development Canada[5] (ESDC) has been selected as the federal department to lead this file. This is expected given that this investment in study abroad programs for Canadian students is framed as foundational to Canada’s future success. Study abroad is argued to equip Canadian students, the future workforce, with the skills and connections needed to succeed in a digital, connected, and global economy; improve access to global trade, investment, research, and business networks; and reinforce the values of openness and inclusion that are essential to Canada’s success as a diverse society (GAC, 2019).

As an outcome of this Strategy, the Global Skills Opportunity program[6] (GSO) was launched to support up to 11,000 college and university undergraduate students to study or work abroad (GAC, 2019). This program aims to provide equal access to international mobility opportunities and diversification of destination countries for underrepresented students, particularly low-income students, Indigenous students, and students with disabilities (GAC, 2019; Universities Canada, 2022b). The GSO accomplishes this by supporting postsecondary institutions’ development and operationalization of study abroad experiences (Universities Canada, 2021). The program is expected to allow over 16,000 postsecondary students to study abroad (Universities Canada, 2021).

At the provincial level, Ontario’s engagement with study abroad traces back to the 1980s with the Four Motors[7] for Europe agreement signed under the Liberal Government which is identified as the beginning of the province’s internationalization activities (Trilokekar & El Masri, 2020; Wolfe, 2000). This partnership included cooperation in many fields including education, where a number of student exchanges for university credit were established and an international education branch was set up in the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities (MTCU) to manage these exchanges (Wolfe, 2000). From 1985 to 1990, Ontario universities actively participated in meetings with their counterparts from the Four Motors to discuss internationalization activities such as supporting academic exchanges, interregional conferences, and seminars on specific subjects sponsored by the partner universities (Featherstone & Radaelli, 2003). However, during the following years of the New Democratic Party (NDP) Government (1994–1995), enthusiasm for the Four Motors program waned due to expenditure restraint (Rachlis & Wolfe, 1997). Interest in international education in general, and study abroad specifically, was reignited in 2005 with the release of the Rae Report (2005) which identified study abroad opportunities for domestic students and marketing Canadian/Ontarian postsecondary education abroad as priority areas. Consequently, the 2005 Ontario budget allocated funds to support developing a new strategy focused on attracting more international students, encouraging study abroad for Ontario students, and raising Ontario’s profile as an international research centre (Ontario Ministry of Finance, 2005). In 2007, the Ontario Ministry re-established the former bilateral student exchanges that were closed down (i.e., with Rhône-Alpes, France, and with Baden-Württemberg, Germany) and added two new ones (with Maharashtra-Goa, India, and with Jiangsu, China). In 2009, it established a new Ontario International Education Opportunity Program (OIEOP) to fund approximately 800 domestic students to study abroad. This, however, is one of very few; Barbarič (2017) observed that Ontario has a limited number of provincially funded study abroad programs which “are hard to find” (p. 6).

It was only in 2018 that the Ministry of Colleges and Universities released Ontario’s International Postsecondary Education Strategy 2018: Educating Global Citizens. The Strategy sets a goal of improving Ontario’s domestic student experience and identifies creating opportunities to study abroad as one of the tools to achieve this goal (MTCU, 2018). The Strategy provided proposals to set study abroad targets and data collection methods to track student participation. However, the Strategy was “a last-gasp policy initiative of a dying government, released a mere few days before the writs were drawn up and a provincial election called” (Barbarič, 2020, p. 182). The new government has not referenced this international education strategy nor (re)initiated discussions around study abroad. Therefore, despite the recent federal investment, the Ontario provincial government does not show a similar commitment to study abroad programs with limited to no funding allocated to this policy file (Barbarič 2017; 2020).

On an institutional level, scholars argued that the Canadian postsecondary education sector, particularly universities, have historically led internationalization initiatives (Beck 2009; Jones, 2009; Shubert et al., 2009; Trilokekar & Jones, 2015a; 2015b; Universities Canada, 2014) with many committing to initiating, sustaining, and expanding their study abroad programs without significant provincial government support. The aforementioned GSO program thus leverages the fact that postsecondary institutions have developed their own internationalization infrastructures by providing funds with which each institution develops their own programming and capacities. As such, in the Ontario college sector, data are needed at the institutional level to generate greater understanding around how institutions might effectively develop study abroad programs.

Barriers to Study Abroad: Global and National Perspective

Study abroad programs have historically been more accessible to students who have ideal health conditions, financial resources to afford the expenses associated with these trips, no/limited familial obligations, and/or strong academic and extracurricular records to win competitive international mobility bursaries and scholarships. This has led to study abroad programs being perceived as “elite” experiences (Holben & Malhotra, 2018). The literature surrounding barriers to international mobility that Canadian students face is not expansive, yet it aligns with global themes (Association of Universities and Colleges Canada, 2014; Behrisch, 2016; CBIE, 2015; Dahl et al., 2013; Kent-Wilkinson et al., 2015; Knight & Madden, 2010; Salyers et al., 2015; Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011; Trower & Lehmann, 2017).

This section reports on barriers to participation in study abroad programs identified in global and national literature, given the lack of provincial literature, which can be categorized as follows: financial barriers; lack of awareness; student perceptions; social, cultural, and familial constraints; gender barriers; institutional constraints; and barriers to minorities. While much of the research focuses on specific types of students and their circumstances, the literature review interprets these findings as resultant of systemic and institutional issues that construct certain college students as having a deficit in capital (Raby, 2019). This framing also informs the implications taken up in the discussion section.

Financial Barriers

Across the global literature surrounding student international mobility experiences in a wide range of countries, the most commonly identified barrier was financial limitation (Murray Brux & Fry, 2010; Bunch et al., 2013; Doyle et al., 2010; Lörz et al., 2016; Petzold & Moog, 2017; Rostovskaya et al., 2020; Taylor & Rivera Jr., 2011; Whatley, 2021). There are significant costs associated with international mobility such as travel accommodation and loss of income for students who have part-time/contract jobs. Lörz et al. (2016) found that higher sensitivity to cost explains the lack of intent formation with regard to studying abroad for German students. Petzold & Moog (2017) explained that German students do not seem to even weigh the beneficial outcomes of studying abroad when sufficient financing is not available. Parental income was found to be positively associated with study abroad engagement for students in the United States (Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2015).

Consistent with global contexts, cost was found to be the primary barrier to international mobility in the Canadian context (Algonquin College, 2021; AUCC, 2014; Behrisch, 2016; Canadian Bureau for International Education, 2015; Dahl et al., 2013; Kent-Wilkinson et al., 2015; Knight & Madden, 2010; Salyers et al., 2015; Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011; Trower & Lehmann, 2017). It was also found that a statistically significant portion of students did not believe study abroad opportunities were worth the cost (Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011). Trower & Lehmann (2017) made the argument that the barriers of time are also financial barriers, in that time incursions equate to further financial burden, resulting in the exclusion of low-income students.

Lack of Awareness

Another theme that emerged from the literature was lack of awareness of available mobility programs, whether as a result of ineffective communication, low user-engagement with communication materials, lack of institutional communication, or other factors; this was found in New Zealand, Russia, and the United States (Doyle et al., 2010; Rostovskaya et al., 2020; Taylor & Rivera Jr., 2011). Regarding the Erasmus program, the largest higher education mobility scheme in Europe, it was found that lack of awareness was a significant factor for both students that considered Erasmus and those that did not, indicating that lack of desire on the part of students was not the critical factor (Souto-Otero et al., 2013). In Russia, it was found that graduate students tend to be more aware of study abroad opportunities (Rostovskaya et al., 2020); however, in the United States, graduate students also tend to participate less as they have more solidified academic plans and field research in comparison to undergraduate students (Stroud, 2010). Students’ lack of awareness of available study abroad opportunities and their perception of lack of suitable and diverse opportunities were also identified as an issue in the Canadian context (Algonquin College, 2021, Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011). Moreover, the Canadian context exhibited disparities in awareness between its sectors; a staggering 43% of college students did not know if study abroad was offered at their institution as compared to 7% of university students (CBIE, 2016b).

Student Perceptions

A recurring theme in the U.S. literature was student perceptions of study abroad importance (Taylor & Rivera Jr., 2011) and safety (Murray Brux & Fry, 2010). Bunch et al. (2013) found that U.S. students generally perceived international experiences as moderately important, with students from urbanized areas perceiving more barriers than those from rural areas or subdivisions. Adding to this general perception, Petzold & Peter (2015), in the German context, made an empirical and theoretical case that there is a social norm that gets developed based on personal experiences such as mobility experience and disciplinary background which results in a disposition towards or away from studying abroad. Dispositions such as wanting to improve one’s understanding of different cultures appeared to encourage students to participate in study abroad experiences.

Student perceptions of their institution were also seen to be significant in a student’s decision to engage in study abroad. When asked whether they believed their institution was committed to global mindedness, only 49% of Canadian students surveyed agreed, with 21% disagreed and 30% unaware (CBIE, 2016b). Furthermore, only 54% agreed that their institution was committed to study abroad, with 20% disagreed and 26% unaware (CBIE, 2016b).

Sociocultural, Linguistic, and Familial Constraints

Additional barriers to student international mobility were found in social and familial constraints, such as aversion to leaving friends, family, and/or dependents (Amani & Kim, 2017; Taylor & Rivera Jr., 2011; Whatley, 2021) However, it is reported that U.S. students who already live far from home in attending their postsecondary institution tend to participate more in study abroad experiences (Stroud, 2010). A specific subset of barriers within cultural constraints were linguistic barriers. The problem of differing languages was also noted as a barrier for student mobility in New Zealand, Russia, and Germany (Doyle et al., 2010; Rostovskaya et al., 2020; Petzold & Moog, 2017), indicating that language was a barrier for both English and non-English speaking countries. In Germany it was found that without foreign language skills, students do not often consider the benefits of study abroad (Petzold & Moog, 2017). In the United States, social commitments such as music/theatre groups, student governance positions, and other extracurricular activities were also seen to reduce the likelihood of participating in study abroad experiences as one may not be able to leave these regularly occurring activities for a long time (Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2015). Social support in study abroad experiences was also determined to be a barrier in New Zealand, as students reported feeling alone during study abroad experiences and would be aided by having group members to travel with (Doyle et al., 2010). Additionally, a study that investigated international student mobility with the Erasmus program suggested that loneliness was further exacerbated by culture shock adversities, which thereby incited feelings of lack of belongingness (Pasztor & Bak, 2019). While these latter two experiences occurred during the study abroad program, they were included as indirect contributors to negative student perception of study abroad.

Consistent with global contexts, Canadian students also faced barriers of social/familial constraints and language barriers (Kent-Wilkinson et al., 2015; Knight & Madden, 2010; Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011). Students with less social support were less likely to study abroad and they also perceived barriers in making friends and understanding the language and culture of another country (Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011).

While gender was not presented as a conventional barrier, it appeared that males were far less likely to participate in student mobility than females (Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2015; Stroud, 2010; Whatley, 2021), at a ratio of almost 1 : 2 in the United States (Salisbury et al., 2010). Salisbury et al. (2010) found that current modes of advertising study abroad suited the formation of intent to study abroad among women which was affected by influential authority figures and educational contexts whereas males’ intents seemed to be shaped by personal values, experiences, and their peers. Bunch et al. (2013) similarly found that U.S. males perceived stronger barriers, especially in rural areas where the need to work in local communities was perceived among males, suggesting that males were more likely to perceive the need to stay home and work in local communities as a result of their rural upbringing. Humanities majors were seen to be more likely to engage in study abroad, which served as a potential explanation for this discrepancy as the humanities skew more towards females; however, even in other fields women still participated in study abroad disproportionately more (Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2015; Salisbury et al., 2010).

Institutional Constraints

A bevy of institutional barriers were noted in the U.S. literature such as inflexible sequential curricular requirements (Murray Brux & Fry, 2010; Taylor & Rivera Jr., 2011) and institutional barriers to faculty members who lead study abroad experiences (Savishinsky, 2012). It was found that there was a disconnect between institutional initiative and rhetoric and the lived experiences of faculty members who had to navigate a complex web of policies, practices, and attitudes that inhibited their ability to lead study abroad experiences (Savishinsky, 2012). This disconnect was seen in the New Zealand context as well wherein exposure to different languages/cultures was a purported benefit of study abroad by the institution, yet most study abroad experiences were with the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada (Doyle et al., 2010). Lack of diverse and plentiful programming was also identified in the U.S. context (Whatley & Raby, 2020). A host of other institutional factors were also identified in the United States such as credit transfer issues, campus culture, program length, and scheduling difficulties (Murray Brux & Fry, 2010), which may suggest a reason for similarly structured higher education systems to interface with one another through study abroad. Another institutional constraint mentioned from the German and U.S. contexts was academic preconditions to study abroad such as GPA requirements which were seen to limit study abroad participation especially with underprivileged students (Lörz et al., 2016; Whatley & Raby, 2020). In the United States, Whatley (2021) found that declaration of a degree objective and higher GPAs predicted greater study abroad participation. College students were also seen to be more likely to study abroad the longer they were enrolled (Whatley, 2019). Not only was the original institution seen to be a limiting factor, but also the host institution. If the host institution was not seen as supportive, students often did not consider the benefits of studying abroad (Petzold & Moog, 2017).

Institutional support also emerged as a significant barrier in the Canadian context in the form of student perceptions around degree completion (AUCC, 2014; Knight & Madden, 2010). The second-largest barrier in two separate studies (Behrisch, 2016; Trilokekar & Rasmi, 2011) was the perception that the study abroad experience would extend time to degree completion, which is not necessarily true. In the former study (Behrisch, 2016), 11% of the students were even discouraged from taking up a mobility program for the aforementioned reason. Additional barriers were found in the application process, wherein students felt that the process was too exacting or complex (Kent-Wilkinson et al., 2015). Canadian students also showed concern for safety and political instability as a barrier to mobility (Kent-Wilkinson et al., 2015).

Barriers to Minorities

Minority participation in study abroad experiences remained disproportionately low for a variety of reasons in the United States including independent factors such as the fear of racism (Murray Brux & Fry, 2010; Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2015; Taylor & Rivera Jr., 2011) and corollary factors such as financial constraints (Covington, 2017; Lee & Green, 2016; Salisbury et al., 2010). However, in the U.S. community college sector, it was found that non-White students are more likely to study abroad, perhaps because of certain equity-promoting policies (Whatley, 2021). This finding stood out markedly from the rest of the literature; Covington (2017) noted that many minority students were already burdened by student loans and cannot go further in debt to pay for study abroad experiences. Murray Brux & Fry (2010) examined minority perspectives to study abroad and found that family constraints also appeared to be an especially pressing issue for minority students, with family disapproval being a significantly limiting factor for Asian, Indigenous, Hispanic, and African American students. While parents often feared discrimination of their children, the students themselves having experienced racism also feared that they may face racism abroad. Gasman (2013) found similar U.S. results in that minority families often held significant fears of the “unknown.” An intersectional study on Black women in the United States provided evidence towards the validity of these fears in revealing that the students were subject to layered racial and gender microaggressions from their host cultures and/or their travelling peers (Willis, 2012). Murray Brux & Fry (2010) also noted that historical patterns of affluent White students participating in study abroad informed current attitudes, and that study abroad programs often had students travelling to Western countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada (Doyle et al., 2010) that are not culturally relevant for many minority students. Salisbury et al. (2011) found that even with significant effort to increase minority participation, study abroad participants were still disproportionately affluent and White. This compounded the problem in the United States in that minority students have less fellow minority peers that can mentor or advise them with respect to study abroad and its benefits (Simon & Ainsworth, 2012). Institutions’ lack of inclusion policies was seen as an additional compounding factor in the United States (Whatley & Raby, 2020)

Only one study identified in the Canadian context referred to the barriers that students with disabilities face. In a report published by Algonquin College (2021), it was identified that the cost of travel was higher for students with disabilities as these students often require extra accommodations and they face logistical challenges that need to be addressed by the institution. Algonquin College (2021) also found that the process is more complex as there are more documents that are required for the aforementioned accommodations.

Another study detailed four major barriers that Indigenous students faced: finances and personal commitments; complications of the process; racism and safety; and lack of an Indigenous approach to study abroad (Wilfrid Laurier University, 2021). The study observed that Indigenous students were disproportionately poorer than other Canadian students and often had multiple dependents; this was compounded with students’ perception that funding decisions and application processes were opaque and led to distrust of the institution. Regarding complications of the process, Indigenous students were seen to be already in a process of cultural learning, which made it difficult for them to be ready for international travel. There were also additional concerns with lack of role models, dedicated support staff, and established relationships. Racism and safety were seen as significant concerns for Indigenous students in that separating from their community made them feel unsafe, and students were unsure if host institutions would be sensitive to Indigenous modes of life. Finally, Indigenous students felt that the lack of Indigenous-focused programming (reciprocal learning and safe, decolonial space, etc.) was a barrier. In Grantham’s (2018) study of Canadian institutional strategic plans, it was found that all but one institution made no reference to the accessibility of mobility programs for Indigenous students. St. Thomas More College was the one exception, wherein goals were set to engage more Indigenous students, to develop more services for Indigenous students, and to provide foundations for Indigenous students to have international experiences (Grantham, 2018).

Counter Narrative

While barrier literature claimed that non-traditional students[8] are less interested in study abroad, scholarship emerging from the United States warn against the deficit narratives that harmfully rationalize college students’ limited participation in study abroad programs (Raby, 2019; Raby & Valeu, 2016). While the barrier literature presented college students’ deficits in cultural, social, and academic capitals to rationalize institutional choices to offer (or not) education abroad opportunities, the counter-deficit narrative challenged these narratives, highlighting the ways in which the college student body has changed. The counter-deficit narrative argued that college students are stereotyped as lacking the interest to participate in study abroad experiences, the academic preparation needed to succeed, and the social and cultural capitals to know how to achieve their goals. This counter-deficit narrative emphasized alternate forms of capitals that current college students have; their awareness of and interest in participating in study abroad experiences; their ability to balance their multiple life roles and responsibilities; and their understanding of the benefits gained on personal, academic, and professional levels (Chen & Starobin, 2017; Quezada & Cordeior; 2016; Zamani-Gallaher et al., 2016). Raby (2019) argued that many of the predefined barriers for college students’ participation in study abroad rarely exist among the current generation of students, and that despite the cost associated with study abroad, students perceived it as good value for their money. However, cost became a barrier when programs were designed to be more accessible to richer students (Raby, 2019). Other scholars also challenged the perception that college students shy away from study abroad because they lack travel experiences, noting that today’s college students are far more travel savvy which makes them less intimidated and fearful of engaging in study abroad experiences (Raby, 2019; Robertson & Blasi, 2017). Therefore, non-traditional college students challenged the assumption that they cannot balance study, including study abroad, into their lives, noting strong family, peer support, mentorship, their ability, and their determination to successfully balance competing priorities (Amani & Kim, 2017; Raby, 2019; Robertson and Blasi, 2017).

Methodology

The study focuses on an Ontario[9] college with a student population of around 30,000. The college offers (advanced) diplomas, bachelor’s degrees, and postgraduate certificates across different disciplines including humanities, social studies, engineering, information technology, business, and health sciences. The college, prior to 2022, had limited study abroad programs that were developed on an ad-hoc basis within only two faculties. There was no internal funding allocated to subsidize students’ study abroad expenses. Between 2015 to 2022, less than 500 students participated in study abroad programs, taking into account the global hiatus on global travel during 2020 to 2022 due to the COVID-19 global pandemic. As such, this study’s survey methodology was chosen with specific aim to generate data at the institutional level, in view of this institution’s specific lack of programming and Ontario’s push of international mobility to the institutional level.

This paper reports on the results of a survey examining students’ attitudes, perceived value, and barriers to study abroad opportunities. The survey asked about their familiarity with and perceptions of education abroad programs identified as travel from Canada to study in another country as part of their academic program/studies. While this study focused on the student body at large, it also examined the perceptions and experiences of three key target groups who were historically marginalized and underrepresented in study abroad opportunities as identified in the GSO program: low-income students, students with disabilities, and Indigenous students.

A survey approved by the ethics board, was developed to gauge students’ experiences, knowledge, and interest in study abroad; perceived value of study abroad; and the perceived barriers to study abroad participation. The survey consisted of a total of 33 closed/multiple-choice questions, and one optional, open-ended question allowing students to provide further input. The questions were designed in consultation with the institution’s research office to ensure that the specific needs of the institution were met with respect to gaps in data that were needed to build effective study abroad programs.

The survey was piloted, and some questions were rephrased to enhance clarity. An invitation to participate in the survey was sent to all students from this Canadian college through their institutional emails and facilitated through Qualtrics, an online survey platform. Participation was completely voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. The survey was open for three weeks in June 2022. In total, 19,501 full-time students received an invitation to participate in the survey, while 490 students responded to at least one question, 376 responded to at least 10 questions, and a total of 335 complete responses were received and analyzed (1.7% response rate). The sample is considered representative at the 95% confidence level (5.33% margin of error) with respect to the entire student population. In order to determine that a survey was complete, a response had to have the last question on the survey completed (and thus every preceding question as well).

Of the limitations of this study is the low response rate which in retrospect may be attributed to the fact that the survey was conducted during the summer when many students were on vacation, except for those who were enrolled in summer classes, and may not have checked their email. Additionally, due to heavy restrictions placed on email blasts to student populations by the research office, it was necessary for the survey to take place during a period where email intensity was low. Furthermore, this study was focused on students at one college and is not necessarily representative of all colleges. In reporting the findings, the report outlines the data for the full population of complete responses. Since the GSO funding program identifies three target groups: low-income students, students with disabilities, and Indigenous students, data pertaining to these students were noted if the findings differed significantly (+/– 10%) from the rest of the total population. Due to the low response rate of students who self-identified as Indigenous students (n = 7), responses to open-ended questions were extracted for findings within this target group. Unfortunately, due to the small sample, we were not able to determine whether the sub-samples for these groups are representative.

Sample Profile

Of all the respondents, 65% were domestic students while the rest (35%) were international. Students were asked about their prior experiences with study abroad and international students were advised to exclude their current experience, 96% of the respondents reported not engaging in a study abroad experience at all, neither during their K–12 nor postsecondary education.

In terms of age groups, 59% were 18–24 years old; 30% were 25–34 years old; and 11% were 35+ years old. In terms of their faculties, the majority of the respondents were enrolled in IT and engineering programs (31%); arts (28%); and business (18%). Most respondents (94%) were full-time students; 39% are enrolled in a bachelor’s program, 32% in a diploma, and 18% in an advanced diploma. The majority of the respondents were in their first year (32%) and second year (30%). In terms of language, 65% of the respondents speak at least two languages (38% speak two languages, 20% speak three, and 7% speak four or more).

In terms of underrepresented students, 39% were of low income, 22% identified as a person with a disability, 3% identified as Indigenous. With regard to dependents, 33% of the respondents identified as a caregiver, providing support to their dependents while also attending postsecondary education.

Findings

The findings of the survey are divided into the following sections: students’ attitudes, interest, perceived benefits, influences and barriers, barrier-free interest, and preferred study abroad program structure. The findings are organized in this manner to reflect the categories of questions, which captured the institution’s data needs, that were asked in the survey.

Students’ Attitudes towards Study Abroad

Students were asked to rate their level of agreement with different statements that gauged their attitudes towards study abroad.

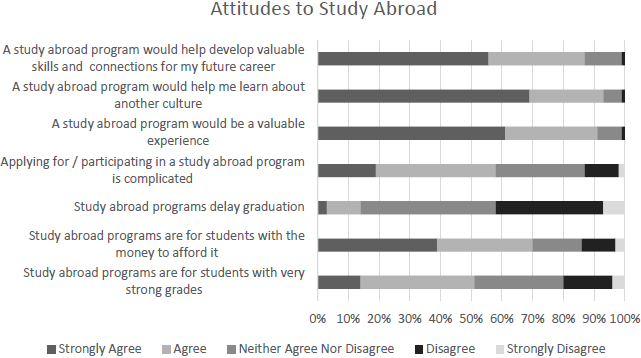

Figure 1

Attitudes to Study Abroad

As Figure 1 illustrates, overall, 61% of students discerned that study abroad will be a valuable experience. With regard to personal development, 69% of students believed that they will be able to learn about a new culture through cultural immersion facilitated by global mobility. One common throughline of the Indigenous students’ responses to open-ended questions was interest in study abroad being driven by a desire to experience new cultures and broaden their worldviews. Study abroad was seen as a valuable experience because of its capacity to open one up to different cultures’ peoples, practices, and norms. On the professional level, 55% of students strongly agreed that global mobility would help develop valuable skills and connections that are beneficial for their future career. That is, they perceive that study abroad may generate more employability since it cultivates valuable skills that are relevant within the workforce.

Despite the generally positive perception regarding the value of study abroad experiences, 70% of the respondents perceived global mobility to be for students with the financial means to afford them, which is consistent with the perception that study abroad is an “elite” experience reported in the literature. Students with disabilities strongly agreed (49%) that study abroad programs are more affordable for students with the money than the rest of the population (39%). As for competitiveness, 51% of the respondents perceived that study abroad programs are for academically strong students. Around 58% of the respondents perceived the process of applying for and participating in study abroad opportunities as complicated, and 14% perceived that participation in study abroad experiences delays graduation. Figure 1 indicates students’ level of agreements with all statements provided.

Interest

When students were asked how interested they were in study abroad, 78% of respondents were very/somewhat interested in participating in study abroad experiences as opposed to 19% who were not overly/not interested at all. International students differed somewhat markedly, with only 9% of international students being not overly/not interested at all in participating in a study abroad experience beyond the one they are engaged in now, and 83% being very/somewhat interested.

Perceived Benefits

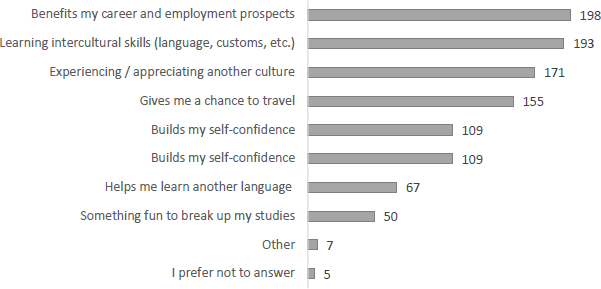

Students were asked to select the top three benefits associated with study abroad that are the most appealing/important to them. The most cited benefits were career and employment prospects (198 responses); learning how to interact (e.g., language and customs) with people from other cultures (193); and experiencing and appreciating another culture (171). One hundred and nine (109) students believed that such an experience has the capacity to build self-confidence (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Perceived Benefits of Study Abroad Experiences

Influences and Barriers

Influences. Students were asked to choose up to two factors that most influence their decision to participate in a study abroad program. Receiving a bursary to offset the travel costs and incurring expenditures was a prominent factor (244 responses). Receiving academic credit was also important for students: with grade (173 responses), as pass/fail (78 responses, or as a note on their co-curricular record (65 responses).

Barriers. Students were asked which three perceived obstacles were most likely to keep them from participating in a study abroad program. Overwhelmingly, financial obstacles were cited as the main hindrance (47.7%). Most students reported that they do not have nor can secure adequate funds to support their study abroad program. Linked to this is a job security concern as many respondents expressed the need to work during the school year and were concerned that if they engaged in a study abroad trip, their jobs might not be held for them during their study abroad experience. The second most cited barrier is academic (23.9%). Students were concerned that participating in a study abroad experience would delay their graduation (13.6%). Others noted that courses are too tightly scheduled which prevent them from participating in study abroad experiences (10.3%). A few did not see the value of a study abroad program within their field of study. Social and familial constraints were also identified as a hindrance to participating in study abroad experiences (12.6%). Students reported concerns regarding being away from their dependents/friends and a few indicated that their parents would not approve their participation in such experiences. Finally, there were concerns regarding accessibility, safety, and support (10.2%). Students expressed concerns regarding their safety and well-being; disability-related concerns, mental health concerns; and lack of comfort in a foreign setting. Students with disabilities also ranked disability-related concerns second in terms of largest obstacles to participation whereas the rest of the population ranked it last.

Barrier-Free Interest. Students were asked how interested they would be in participating in a study abroad program if there were no barriers. The vast majority (91%) were very/somewhat interested in partaking in a study abroad program. While, as discussed earlier, 78% of the respondents were very/somewhat interested in participating in study abroad experiences, once barriers are removed, 91% are very/somewhat interested. This suggests the need for more inclusive study abroad programs by addressing the financial; academic; social/familial responsibilities; and accessibility, safety, and support concerns.

Preferred Study Abroad Program Structure

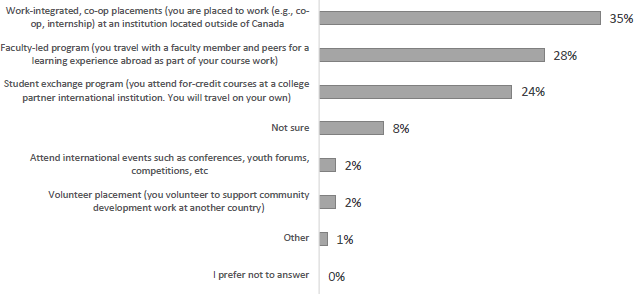

Students were asked to review different study abroad programs that the institution could feasibly offer and to indicate which they would most prefer (Figure 3). The most preferred modalities were work-integrated opportunities wherein students are placed in a work opportunity at an institution located outside of Canada (35%), faculty-led exchange wherein students travel with a faculty member and peers for a learning experience abroad as part of their coursework (28%), and student exchange wherein students attend courses for which they gain credit for at a partner international institution. Student travel on their own without being accompanied by a faculty member (24%). Low-income students and students with disabilities were more likely to opt for faculty-led programs and less likely to prefer a work-integrated or co-op placement study abroad program.

Figure 3

Preferred Study Abroad Program

Students were asked about their preferred study abroad program structure. In terms of the language, the majority (66%) of students were somewhat/very likely to choose to travel to a country where English or a language they speak is not widely spoken. In terms of location, students were more interested in travelling to Europe, Asia, Australia/Oceania, and North America. In terms of length of their study abroad experience, 44% of the respondents preferred a semester-length program, 12% of students opted to attend a program that lasts for a duration of more than one semester, 11% of the participants preferred their program to last up to 3–4 weeks in duration and 5% chose a 1–2-week program. As for the semester they would like their study abroad experience to occur in, the majority (35%) held that they had no preference, with the other semesters being roughly evenly distributed in preference and the Winter semester being slightly preferred over other semesters.

Discussion and Conclusion

Students in this study were interested in study abroad opportunities which challenges the deficit narrative that constructs college students, usually non-traditional[10], as lacking the academic, social, and cultural capitals to manifest their interest in engaging in study abroad experiences (Raby, 2019). The data in this study reveal asset-based perspective. With respect to the first research question, students perceived study abroad experiences as an opportunity that enhance professional, intercultural, linguistic, and interpersonal skills and competencies. Unsurprisingly, given the nature of college education, college students particularly value transferable skills that would advance their professional portfolio. Therefore, this study supports Raby’s (2019) challenge of the narrative that study abroad is an “unnecessary luxury” and “superfluous to a career pathway” for college students (p. 4).

However, despite their interest in study abroad, many students face real and perceived barriers to participating in these experiences. While 78% initially indicated interest in study abroad experiences; once the (perceived) barriers were removed, 91% affirmed that they would be very/somewhat interested. This attests to the fact that students are thinking about studying abroad and have the motivation to participate, but there is a need for more inclusive study abroad programs that address the main barriers: financial; academic; social/familial constraints; and accessibility, safety, and support concerns. It is the institutional choice rather than the students’ interest that accounts for increasing participation in study abroad experiences.

While this study supports the “counter deficit narrative” in terms of current college students’ willingness to participate in study abroad experiences and their appreciation of its cultural, academic, and professional value, it also highlights that some of the traditional barriers persist. Financial obstacles remain the most cited barrier. Balancing their study, work, and personal lives is a concern as they worry that engaging in study abroad will risk their ability to keep their jobs, delay their graduation, and/or influence their ability to support their dependants. Therefore, it is important for governments and colleges to invest in learning more about their student body and respond to their specific needs and goals.

To enhance college students’ participation in study abroad opportunities, systemic change in Canada and Ontario’s study abroad infrastructure is needed. The burden will have to be carried by more than just colleges relying on insufficient federal support and nonexistent provincial support. In the next two sections we propose a coordinated and sustained approach through more inclusive policies, protocols, recruitment strategies, and design of the mobility programs to address those barriers on the governmental as well as collegiate level.

Governmental Programming

The federal government’s GSO pilot program represents a “breakthrough” in Canada’s approach to study abroad that scholars have called for: a national strategy with clear objectives, priorities, targets, and tracking of progress (Biggs & Paris, 2017, p. 20). However, in the grand picture of 3.5 million postsecondary students, the response is still rather limited. There is hope that this pilot program will be expanded in the future to allow postsecondary institutions to develop more inclusive and sustainable study abroad programs and expand student participation. Out of the 309 publicly funded postsecondary institutions (96 universities and 213 colleges and institutes), a total of 100 postsecondary institutions participated in this pilot program, 56 are universities and 44 of them are colleges (Colleges and Institutes Canada, 2022; Universities Canada, 2022c). That is, only 32% of Canadian postsecondary institutions have participated and 21% of colleges. It is important to evaluate the implementation of the GSO projects at participating institutions, examining student experiences, successes, and challenges. Of particular importance is to understand why 68% of postsecondary institutions (including 79% of colleges) did not participate in this pilot program; distinguishing between lack of institutional interest, lack of student interest, lack of resources, and/or other factors will help guide future initiatives.

The continuation, sustainability, and integration of this GSO program into future iterations of Canada’s international education strategies is important to achieve tangible results though a long-term coordinated and collaborative effort involving government, educational institutions, faculty, students, partner organizations, and other stakeholders. As this program is still ongoing, further studies are needed to examine its outcomes in terms of participating students’ experiences, institutional interest and commitment, diversity of study abroad destinations, etc. These data would also help to inform future iterations of the program.

Given that education remains a provincial responsibility constitutionally, it is critical that the Government of Ontario plays a stronger role in championing and leading a coordinated provincial strategy towards international education in general, including study abroad. This would set a much-needed roadmap to increasing Ontario college students’ participation in study abroad, encouraging and incentivizing institutions to establish/expand their study abroad programs, and allocating resources to support institutions in developing strong, sustainable infrastructure and equitably funding students.

College Programming

Colleges need to understand the changing dynamics of their students including their strengths and interests. Understanding their demographics would help avoid detrimental deficit stereotypes and allow them to develop more proactive strategies, inclusive and accessible programming, and targeted communication.

Strategy Setting. While integrating study abroad and mobility programs into the institutional strategy is important, this needs to be accompanied by a clear road map and invested resources towards achieving this goal. To develop more inclusive and accessible study abroad programs, postsecondary institutions need a holistic approach that involves target setting, financial investments, well-designed programs that are tailored to the unique needs of their student body, and a solid support infrastructure that supports students’ physical, mental, and academic well-being.

Inclusive, Accessible Programming. To ensure equity in practice, it is crucial for institutions to be informed of the real and perceived barriers their students (expect to) encounter during their study abroad to proactively address potential gaps in their existing programming and inform the design of new ones. In designing inclusive study abroad programs, it is paramount to ensure that a strong infrastructure is developed to address the unique needs of students, particularly underrepresented students, by providing holistic wrap-around services. As financial barriers were the most cited obstacles to study abroad, developing and deploying financial support to create a more inclusive study abroad system is key. While seeking external funding sources such as the GSO program and other public and/or private funding sources is beneficial, it is important to allocate internal funds to reflect institutional commitment towards the sustainability of these programs. Institutions also need to critically reflect on who has access to their study abroad experiences and whether these experiences are reserved and/or more accessible to high-grade attaining students. Exploring ways to open up opportunities to students along the spectrum of academic achievement and providing supports accordingly is a critical path to equitable study abroad infrastructure.

Study Abroad and College Programming. Many students choose college education for its unique blend of academic learning and practical skills training, close link to industry, and focus on building students’ skills to get them working fast (Colleges Ontario, 2013). Therefore, college programs, particularly diplomas and postgrad certificates, tend to be shorter, more intensive, and hands-on in nature. One problem that arises out of this compact course duration is that it lends itself to shorter study abroad program lengths. This conflicts with students’ desire for longer-term study abroad programs. Colleges will need to create robust partnerships with international institutions to develop study abroad solutions that allow students to absorb the benefits of a semester or more abroad without suffering a credit opportunity cost. It is important that colleges update their curricula and integrate international learning opportunities into their programs and embrace a more flexible approach to recognizing international learning experiences whether through granting credits and/or extra recognition to those who participate in global educational experiences. It is not surprising that college students prefer work-integrated learning study abroad experiences that provide them with valuable global work experiences and professional networks. However, it is important to note that underrepresented students (particularly, students with disabilities and low-income students) prefer to travel within a cohort and accompanied by a faculty member. This might be attributed to a heightened need for safety and/or support systems.

Communication. It is reported that 43% of college students did not know if study abroad was offered at their institution as compared to 7% of university students (CBIE, 2016). It is recommended that institutions develop communication campaigns to raise awareness of the availability of study abroad opportunities and to explain their benefits. More importantly, this communication should outline the steps undertaken to make the opportunities more accessible to their unique student body, acknowledging their concerns/perceived barriers and outlining available resources and support infrastructure available. This may include providing incentives to underrepresented students and assigning study abroad student ambassadors to share their lived experiences.

To summarize, in order to enhance college students’ participation in study abroad opportunities, it is important to steer away from stereotyping college students as uninterested, unmotivated, and/or incapable of participating in study abroad opportunities. Colleges need to seek to understand the challenges, needs, and goals of their student body and design inclusive opportunities for all students accordingly. Governments can further incentivize and support colleges through targeted funding and partnership programs. More studies in the Canadian context are needed to examine institutional discourse, strategies, and programs around education abroad. While this study partially supports the “counter deficit narrative” and reveals college students’ interest in education abroad, it also acknowledges that the traditional financial, academic, social/familial constraints and accessibility barriers persist. Further investigation of the institutional and student perspectives is required.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Amira El Masri, PhD, is a higher education researcher and professional. Her areas of research focus are international education policymaking, international student experiences, and internationalizing teacher education. She has worked in a range of senior international education strategy-oriented roles nationally and internationally. Currently, she is the director of the Office of International Affairs at McMaster University.

Noah Khan is a PhD student in social justice education at the University of Toronto. His research is situated in phenomenology of technology, seeking to philosophically explore the experiential elements of digital encounters. Noah is a CGS-D Scholar, Massey College Junior Fellow, Evasion Lab Fellow, School of Cities Fellow, and Reach Alliance Researcher.

Notes

-

[1]

Study abroad programs are defined as educational experiences that require students to travel outside of their country. Examples include international work-integrated learning programs, faculty-led trips, summer school abroad, and volunteer abroad opportunities.

-

[2]

The Erasmus Program (2009–2013) focused on student and staff mobility between universities. The Erasmus+ Program (2014–2020) includes further opportunities for staff and students from all levels of education to study, train, or volunteer abroad.

-

[3]

Institutionally, across Canada, there are both universities and colleges. The latter go by a few names and can be referred to as community colleges, colleges of applied arts and technology (or design), institutes of technology, polytechnics, and also CEGEPs (in the province of Quebec). In general, colleges are concerned with technical and vocational education and training. Scholars observe that the boundary between universities and colleges are increasingly becoming blurred as more colleges are receiving authorization to offer bachelor’s degrees (Skolnik, 1997). In general, the college sector generally represents International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) Levels 4 & 5, with select institutions covering ISCED 6. The university sector, on the other hand, generally covers ISCED 6–8, with many offering ISCED 5 programs (Usher, 2021)

-

[4]

Canada’s college sector is also bifurcated into those that have English and those that have French as their main language of instruction. These latter, largely located in the province of Quebec, known as CEGEPs (College of General and Professional Teaching), have marked differences. They are entered into after Grade 11 and offer both 2-year preuniversity programs and 3-year technical programs. As such, the age profile is quite different from English-instruction colleges. Despite these differences, the participation rate in study abroad programs at CEGEPs, 2.3% (Bégin-Caouette et al., 2023), is roughly similar to English-instruction colleges when considering that 50% of the CEGEP students who study abroad are enrolled in the 3-year technical programs, resulting in a comparable rate of 1.15% (Bégin-Caouette et al., 2014). Higher education in Canada, colleges and universities, is publicly funded (with a few private colleges) and many students move between colleges and universities fluidly. After their university degree, 19.4% of university graduates choose to enroll in a college (25.8% in Ontario).

-

[5]

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) is a federal unit tasked with promoting a labour force that is highly skilled and promoting an efficient and inclusive labour market.

-

[6]

The GSO is the Government of Canada’s Outbound Student Mobility pilot program, which aims to empower postsecondary institutions to increase the participation of young Canadians—especially underrepresented students—in international learning opportunities both at home and abroad.

-

[7]

The first agreement was signed by the Ontario provincial government in 1986 with Baden-Württemberg, Germany, followed by the agreements with Rhône-Alpes, France; Lombardy, Italy, in 1989; and Catalonia, Spain, in 1990 (Wolfe, 2000).

-

[8]

Non-traditional students are defined as low income, students of colour, first generation college student, full time worker, and/or above 25 years.

-

[9]

Ontario is Canada’s second largest province in terms of area, occupying 11% of Canada’s total area; it is Canada’s most populated province, comprising roughly 40% of the Canadian population (Statistics Canada, 2022) and it has the largest postsecondary education sector among all of Canada’s provinces.

-

[10]

Non-traditional students are defined as low income, students of colour, first generation college student, full-time worker, and/or above 25 years in age.

Bibliography

- Algonquin College. (2021). Mobility by design: Outbound mobility of Canadian college students. https://www.algonquincollege.com/arie/2021/03/mobility-by-design-outbound-mobility-of-canadian-college-students/

- Amani, M., & Kim, M. M. (2017). Study abroad participation at community colleges: Students’ decision and influential factors. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 42(10), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2017.1352544

- Association of Universities and Colleges Canada. (2014). Canada’s universities in the world: AUCC internationalization survey 2014. https://www.univcan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/internationalization-survey-2014.pdf

- Barbarič, D. (2017). Policy options for outbound student mobility: An inter-jurisdictional review of policy goals and initiatives. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31043.71205

- Barbarič, D. (2018). Is outbound student mobility back? Centre for the Study of Canadian and International Higher Education. https://ciheblog.wordpress.com/2018/05/22/is-outbound-student-mobility-back/

- Barbarič, D. (2020). The politics behind and the value of outbound student mobility: Is Canada missing the boat? [Doctoral thesis, University of Toronto]. TSpace.

- Beck, K. (2009). Questioning the emperor’s new clothes: Towards ethical practices in internationalization. In R. Trilokekar, G. A. Jones, & A. Shubert (Eds.), Canada's universities go global (pp. 306–336). James Lorimer and Company.

- Bégin-Caouette, O., Angers, V., & Niflis, K. (2014). Increasing participation in study abroad programs: Organizational strategies in Quebec CEGEPs. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(6), 568–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2013.865003

- Bégin-Caouette, O., Francis Hazoume, O., & Berthiaume, D. (2023). Democratizing access to an international experience through digital technology. Pédagogie collégiale, 36(2), 50–60. https://eduq.info/xmlui/handle/11515/38773

- Behrisch, T. (2016). Cost and the craving for novelty: Exploring motivations and barriers for cooperative education and exchange students to go abroad. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 17(3), 279–294.

- Biggs, M., & Paris, R. (2017). Global education for Canadians equipping young Canadians to succeed at home & abroad. Centre for International Policy Studies, University of Ottawa, and Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. https://844ff178-14d6-4587-9f3e-f856abf651b8.filesusr.com/ugd/dd9c01_ca275361406744feb38ec91a5dd6e30d.pdf

- Bunch, J. C., Lamm, A. J., Israel, G. D., & Edwards, M. C. (2013). Assessing the motivators and barriers influencing undergraduate students’ choices to participate in international experiences. Journal of Agricultural Education, 54(2), 217–231. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1122301.pdf

- Canadian Bureau for International Education. (2015). Canada’s performance and potential in international education 2015. http://www.cbie.ca/about-ie/facts-and-figures/#_ednref8

- Canadian Bureau for International Education. (2016). A world of learning: Canadian post-secondary students and the study abroad experience. https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/20100520_WorldOfLearningReport_e1.pdf

- Canadian Bureau for International Education. (2022). Did you know? cbie.ca

- Chen, Y., & Starobin, S. S. (2017). Measuring and examining general self-efficacy among community college students: A structural equation modelling approach. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 42(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/:10.1080/10668926.2017.1281178

- Colleges and Institutes Canada. (2022). Global skills opportunity—A year in review: 2021–2022 annual narrative report. https://globalskillsopportunity.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Annual-Report-CICan-GSO.pdf

- Colleges Ontario. (2013). Why choose college in Ontario? https://www.ontariocolleges.ca/en/colleges/why-college

- Covington, M. (2017). If not us then who? Exploring the role of HBCUs in increasing Black student engagement in study abroad. College Student Affairs Leadership, 4(1), 5.

- Dahl, A., Prouse, S., Sheppard, G., Squires, V., & Tannis, D. (2013). Study abroad assessment report for the College of Arts and Sciences. International Student Study Abroad Centre, University of Saskatchewan. https://share.usask.ca/nursing/irg/References/AS_StudyAbroadAssessment_Report_FinalJanuary_2013.pdf

- Doyle, S., Gendall, P., Meyer, L. H., Hoek, J., Tait, C., McKenzie, L., & Loorparg, A. (2010). An investigation of factors associated with student participation in study abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education, 14(5), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315309336032

- El Masri, A. (2019). International education as policy: A discourse coalition framework analysis of the construction, context, and empowerment of Ontario’s international education storylines. [Doctoral dissertation, York University]. YorkSpace.

- Eurostat. (2022, June). Learning mobility statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Learning_mobility_statistics#:~:text=Highlights&text=1.46%20million%20students%20from%20abroad,across%20the%20EU%20in%202020.&text=In%202020%2C%20students%20from%20abroad,and%209%20%25%20in%20the%20Netherlands.

- Featherstone, K., & Radaelli, C. (2003). The politics of Europeanization. Oxford University Press.

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. (2014). Canada’s international education strategy: Harnessing our knowledge advantage to drive innovation and prosperity. https://www.international.gc.ca/education/assets/pdfs/overview-apercu-eng.pdf

- Gasman, M. (2013). The changing face of historically Black colleges and universities. Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions. https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/335

- Global Affairs Canada. (2019). Building on success: International education strategy (2019–2024). https://www.international.gc.ca/education/strategy-2019-2024-strategie.aspx?lang=eng

- Grantham, K. (2018). Assessing international student mobility in Canadian university strategic plans: Instrumentalist versus transformational approaches in higher education. Journal of Global Citizenship & Equity Education, 6(1). https://journals.sfu.ca/jgcee/index.php/jgcee/issue/view/9

- Holben, A., & Malhotra, M. (2018). Commitments that work. In N. Gozik & H. B. Hamir (Eds.), Promoting inclusion in education abroad: A handbook of research and practice (pp. 99–113). Stylus & NAFSA.

- Jones, G. A. (2009). Internationalization and higher education policy in Canada: Three challenges. In R. Trilokekar, G. A. Jones, & A. Shubert (Eds.), Canada's universities go global (pp. 355–369). James Lorimer and Company.

- Kent-Wilkinson, A., Leurer, M. D., Luimes, J., Ferguson, L., & Murray, L. (2015). Studying abroad: Exploring factors influencing nursing students’ decisions to apply for clinical placements in international settings. Nurse Education Today, 35(8), 941–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.03.012

- Knight, J., & Madden, M. (2010). International mobility of Canadian social sciences and humanities doctoral students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 40(2), 18–34. http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/cjhe/article/view/1916

- Lee, J. A., & Green, Q. (2016). Unique opportunities: Influence of study abroad on Black students. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 28(1), 61–77. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1123202

- Lörz, M., Netz, N., & Quast, H. (2016). Why do students from underprivileged families less often intend to study abroad? Higher Education, 72(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9943-1

- Luo, J., & Jamieson-Drake, D. (2015). Predictors of study abroad intent, participation, and college outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 56(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9338-7

- Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities. (MTCU). (2018). Ontario's international postsecondary education strategy 2018: Educating global citizens. https://www.tcu.gov.on.ca/pepg/consultations/maesd-international-pse-strategy-en-13f-spring2018.pdf

- Murray Brux, J., & Fry, B. (2010). Multicultural students in study abroad: Their interests, their issues, and their constraints. Journal of Studies in International Education, 14(5), 508–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315309342486

- Ontario Colleges Library Service. (2023). College FTEs. https://www.ocls.ca/colleges/ftes

- Ontario Ministry of Finance. (2005). Ontario budget 2005: Backgrounder: Reaching higher: The plan for postsecondary education. http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/budget/ontariobudgets/2005/pdf/bke1.pdf

- Pasztor, J., & Bak, G. (2019). The urge of share & fear of missing out—Connection between culture shock and social media activities during Erasmus internship. Proceedings of FIKUSZ Symposium for Young Researchers, 176–191. https://kgk.uniobuda.hu/sites/default/files/FIKUSZ2019/FIKUSZ_2019_20_181.pdf

- Petzold, K., & Moog, P. (2017). What shapes the intention to study abroad? An experimental approach. Higher Education, 75, 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0119-z

- Petzold, K., & Peter, T. (2015). The social norm to study abroad: Determinants and effects. Higher Education, 69(6), 885–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9811-4

- Popovic, T. (2013, May). International education in Ontario colleges: Policy paper. Toronto, ON: College Student Alliance. http://collegestudentalliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/internationalFINAL.pdf

- Quezada, R. L., & Cordeior, P. A. (2016). Creating and enhancing a global consciousness among students of color in our community colleges. In R. L. Raby & E. J. Valeau (Eds.), International education at community colleges: Themes, practices, research, and case studies (pp. 335–355). New York. Palgrave.

- Raby, R. L. (2019). Changing the conversation: Measures that contribute to community college education abroad success. In G. F. Malveaux & R. L. Raby (Eds.), Study abroad opportunities for community college students and strategies for global learning (pp. 1–21). IGI Global.

- Raby, R. L., & Valeau, E. J. (2016). International education at community colleges: Themes, practices, research, and case studies. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillian Publishers. https://doi.org/:10.1057/978-1-137-53336-4

- Rachlis, C., & Wolfe, D. (1997). An insider’s view of the NDP Government in Ontario: The politics of permanent opposition meets the economics of permanent recession. In G. White (Ed.), The government and politics of Ontario (pp. 331–364). University of Toronto Press.

- Rae, B. (2005). Ontario: A leader in learning. Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities. https://ucarecdn.com/826771e2-3c0d-47d6-857f-33224d47e1b2/

- Robertson, J. J., & Blasi, L. (2017). Community college student perceptions of their experiences related to global learning: Understanding the impact of family, faculty, and the curriculum. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 41(11), 697–718. https://doi.org/:10.1080/10668926.2016.1222974

- Rostovskaya, T. K., Maksimova, A. S., Mekeko, N. M., & Fomina, S. N. (2020). Barriers to students’ academic mobility in Russia. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(4), 1218–1227. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/79d0/e63b07be028fc1f18bbe082104c9faab454c.pdf

- Salisbury, M. H., Paulsen, M. B., & Pascarella, E. T. (2010). To see the world or stay at home: Applying an integrated student choice model to explore the gender gap in the intent to study abroad. Research in Higher Education, 51(7), 615–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9171-6

- Salisbury, M. H., Paulsen, M. B., & Pascarella, E. T. (2011). Why do all the study abroad students look alike? Applying an integrated student choice model to explore differences in the factors that influence white and minority students’ intent to study abroad. Research in Higher Education, 52(2), 123–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9191-2

- Salyers, V., Carston, C. S., Dean, Y., & London, C. (2015). Exploring the motivations, expectations, and experiences of students who study in global settings. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 368–382. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v5i4.401

- Savishinsky, M. (2012). Overcoming barriers to faculty engagement in study abroad. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington]. ResearchWorks Archive.

- Shubert, A, Jones, G. A., & Trilokekar, R. (2009). Introduction. In R. Trilokekar, G. A. Jones, & A. Shubert (Eds.), Canada's universities go global (pp. 6–15). James Lorimer and Company.

- Simon, J., & Ainsworth, J. W. (2012). Race and socioeconomic status differences in study abroad participation: The role of habitus, social networks, and cultural capital. International Scholarly Research Network. https://doi.org/:10.5402/2012/413896

- Skolnik, M. L. (1997). Putting it all together: Viewing Canadian higher education from a collection of jurisdiction-based perspectives. In G. A. Jones (Ed.), Higher education in Canada: Different systems, different perspectives (pp. 325–341). Garland.

- Souto-Otero, M., Huisman, J., Beerkens, M., De Wit, H., & Vujić, S. (2013). Barriers to international student mobility: Evidence from the Erasmus program. Educational Researcher, 42(2), 70–77. https://doi.org//10.3102/0013189X12466696

- Statistics Canada. (2022). Postsecondary enrolments by institution type, registration status, province and sex (Both sexes): 2014/2015. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/educ71a-eng.htm

- Stroud, A. H. (2010). Who plans (not) to study abroad? An examination of US student intent. Journal of Studies in International Education, 14(5), 491–507. https://doi.org//10.1177/1028315309357942

- Taylor, M., & Rivera Jr, D. (2011). Understanding student interest and barriers to study abroad: An exploratory study. Consortium Journal of Hospitality & Tourism, 15(2), 56–72. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Rivera-2/publication/260106333_Understanding_student_interest_and_barriers_to_study_abroad_An_exploratory_study/links/5703aaab08aedbac127084f8/Understanding-student-interest-and-barriers-to-study-abroad-An-exploratory-study.pdf

- Trilokekar, R., & El Masri, A. (2016). Canada’s international education strategy: Implications of a new policy landscape for synergy between government policy and institutional strategy. Higher Education Policy, 29, 539–563.

- Trilokekar, R., & El Masri, A. (2017). The ‘[h]unt for new Canadians begins in the classroom’: The construction and contradictions of Canadian policy discourse on international education. Globalisation, Societies, and Education, 15(5), 666–678. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2016.1222897

- Trilokekar, R. & El Masri, A. (2020). International education policy in Ontario: A swinging pendulum? In R. Trilokekar, M. Tamtik, & G. Jones (Eds.), International education as public policy in Canada (pp. 247–266). McGill-Queen’s University Press. https://www.mqup.ca/international-education-as-public-policy-incanada-products-9780228001768.ph

- Trilokekar, R., & Jones, G. A. (2015a). Internationalizing Canada's universities. International Higher Education, 46. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2007.46.7942

- Trilokekar, R., & Jones, G. A. (2015b). Finally, an internationalization policy for Canada. International Higher Education, 71, 17–18. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2013.71.6089