Abstracts

Abstract

Jorge Soto Gallo disappeared on July 15, 1985, during a trip from Medellín to Bogotá in Colombia. Jorge is one of the thousands of disappeared people in Colombia whose families are still searching for answers, yet Jorge’s life and disappearance have been memorialized and recorded through his sister’s work of preserving, cultivating, and activating his personal archive. During recent decades, families of disappeared persons have begun to assemble folders that carry the evidence of disappearances. This article explores the personal archive of Jorge Soto Gallo with the aim of understanding a recordkeeping practice carried out by families and communities, which focuses on disappeared persons and often leads to a broad repertoire of political activism in defence of human rights. We ask, Which records are included, how are they brought together during these periods of upheaval, what do they mean, and what role do they play? We argue that creating and preserving these archives of enforced disappearance act as liberatory memory work (LMW) and as instincts of the families against forces of impunity and oblivion. We show that LMW is a living reality in Colombia that operates on a person-centred level, going beyond transitional justice frameworks, and turning victims into recordkeepers providing the possibility of historical accountability for future generations.

Résumé

Jorge Soto Gallo est disparu le 15 juillet 1985 lors d’un voyage entre Medellín et Bogotá, en Colombie. Jorge est l’un des milliers de personnes disparues en Colombie dont les familles cherchent toujours des réponses. Toutefois, la vie et la disparition de Jorge ont été commémorées et documentées par le travail de préservation, d’engagement et d’activisme de sa soeur. Au cours des dernières décennies, les familles de disparu.e.s ont commencé à regrouper des dossiers qui portent l’évidence de disparitions. Cet article explore les archives personnelles de Jorge Soto Gallo avec comme objectif de comprendre une pratique de collection d’archives entreprise par les familles et communautés, qui met l’accent sur les personnes disparues. Cette pratique conduit souvent à un activisme politique se portant à la défense des droits de la personne. Nous demandons alors: Quels documents sont inclus? Comment sont-ils regroupés dans ces périodes de bouleversements? Que signifient-ils et quel rôle jouent-ils? Nous soutenons que l’action de créer et de préserver ces archives de disparition par la force agit comme un travail de mémoire libérateur et se produit instinctivement pour les familles se trouvant en opposition face aux forces d’impunité et de l’oubli. Nous démontrons que le travail de mémoire libérateur centré sur les personnes est une réalité vivante en Colombie. Ce travail va ainsi plus loin que le cadre de justice transitionnelle. La transformation des victimes en archivistes offre des possibilités de responsabilité historique pour les générations futures.

Article body

Introduction[1]

Jorge Soto Gallo disappeared on July 15, 1985, during a trip from Medellín to Bogotá. He was travelling with a friend to participate in a congress of the recently created Unión Patriótica (UP) party. They never arrived at their destination, nor have they been seen to this day. Between 1985 and 1993, the UP was swiftly exterminated in a systematic exercise of massacres, disappearances, and persecution.[2] Jorge is one of the thousands of disappeared people in Colombia whose families are still searching for answers.[3] Yet, Jorge’s life and disappearance have been memorialized and recorded through his sister’s work of preserving, cultivating, and activating his personal archive.

During recent decades, families of disappeared persons (“the families”) have begun to assemble folders of papers that carry the evidence of disappearances. There is a difference between the crime of enforced disappearance and other crimes. Due to government denial and the absence of bodies, families must prove that crimes were committed in the first place. These folders, created to prove each disappearance, hold personal tales of stagnated searches, trauma, depression, and anger – but also hope, love, care, and resistance.

This article explores the personal archive of Jorge Soto Gallo with the aim of highlighting a recordkeeping practice driven by families and communities, which focuses on disappeared persons and often ends up as part of a broad repertoire of political activism in favour of the defence of human rights – a practice of evidentiating absences and demanding truth and justice despite ongoing threats, which ends up materializing in personal human rights archives. We ask, Which records are included, how are they brought together during these periods of upheaval, what do they mean, and what role do they play?

We begin by looking into the background of Jorge’s disappearance. We provide an overview of the literature on personal archives in cases of mass violations and then give a brief description of the archive’s holdings. We then analyze these personal documents in relation to their creator, their subject matter, and their relationships to each other and a broader community. The creator of this archive is Jorge’s sister, Martha Soto Gallo. The conversational interviews to which Martha graciously agreed,[4] along with the study of her records, are the basis of our inductive research. Martha herself is a registered victim of forced displacement due to death threats and persecution. Despite this, when asked about anonymization for the interview, Martha said it was crucial for her to name and “make visible” her brother and his case. She told us, “What isn’t named, doesn’t exist” (Lo que no se nombra no existe).[5]

We are inspired by the work of Jennifer Douglas and Alexandra Alisauskas[6] to approach our work generously and respectfully. We centre the voices and experiences of Martha, Jorge, and their family in this article to show the work a record can do in a context of oblivion and to highlight the work of the recordkeeper.[7] Relevant here is not only the archive itself but also, above all, the documentation practices behind its creation and the meanings attributed to them, the contexts of production, and the use of the archive. We argue that creating and preserving these archives of enforced disappearance act as liberatory memory work (LMW) – an instinct of the families against forces of impunity and oblivion. We take up this concept from Chandre Gould and Verne Harris, who in a 2014 report for the Nelson Mandela Foundation proposed the concept of LMW to allude to practices that work with the past, insist on accountability, acknowledge and attempt to address pain and trauma, and reveal the hidden dimensions of human rights violations.[8] We show LMW as a living reality in Colombia that operates on a person-centred level, going beyond transitional justice frameworks, turning victims into recordkeepers, and providing the possibility of historical accountability for future generations.

The Context of Jorge’s Case

Enforced disappearance has been categorized as a crime by the 1998 Rome Statute, the 1992 Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, where it is defined as

the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.[9]

Officially, Colombia’s history of enforced disappearance goes back to the 1970s, although unofficially, the practice was already taking place for some time before.[10] The practice intensified during the 1980s as the Colombian state embraced a policy of “dirty war,” like so many other states in the region.[11] Cold War macro-narratives against communism legitimized violence against political movements that were framed as “subversive elements.”[12]

In 1985, the Unión Patriótica (UP) was born out of a peace agreement between the guerrilla group FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) and the government. It soon became a popular political party that integrated a variety of individuals from different backgrounds, including members of the Communist Party and unions, workers, peasants, intellectuals, teachers, students, and demobilized guerrilla fighters.[13] From 1988 to 1990, however, the party was weakened by systematic targeted assassinations, raids on UP offices, illegal detentions, massacres, and threats against not only activists but also their relatives, which led to forced displacement. The systematic violence perpetrated against this new leftist political party left a clear message in the regions where it took place: that “the UP had to disappear, or the people would suffer.”[14] Between 1985 and 2002, the UP was exterminated as a political party.[15]

The attorney general’s office reported 1,620 fatalities related to the UP during this period. However, the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Corporación Reiniciar identified 6,613 victims of 9,359 violations between 1984 and 2002 (one victim may have suffered more than one victimizing act).[16] The Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica identified 6,201 victims, 544 of whom were victims of enforced disappearance. Jorge Soto Gallo, who joined the UP in 1984, was one of the first party members subjected to enforced disappearance.[17]

The case of the UP has been overlooked in overall research on Colombia and considered to be only another episode of the armed conflict. But the destruction of the UP went further than the destruction of a political party, due to the targeting of families and their social networks.[18] Researchers such as Gomez- Suarez and Carroll have analyzed this destruction as genocide.[19] Whether it was a genocide or not is not the focus of this study, but raising this point helps to contextualize the impact of this destruction on Colombian society and individuals. In contrast to its objective importance, its victims have received rather little sympathy in Colombia due to their image as subversive elements.[20]

The work of the families and organizations through the years led to a case against the government at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2018, and in February 2019, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP in Spanish), a Colombian transitional justice (TJ) mechanism, opened a case on violations against UP members, case no. 6. The case qualified for prioritization due to the systematic violence unleashed on the UP’s members and community, which violated several human rights and international humanitarian law. This means the case will now be investigated as one of the main incidents of the Colombian armed conflict.[21] For the relatives of the UP victims, this action opens the possibility that the crimes their loved ones were subjected to will not go unpunished and, to the extent possible, reparations will be made.

Literature on Personal Archives in Contexts of Mass Human Rights Violations

With the postmodern turn in archival studies, there has been a rise in interest in personal archives, defined as collections generated by individuals during their lifetimes.[22] They record

the personal, the idiosyncratic, the singular views of people as they go about doing the things that they do and commenting on them. Personal archives, then, are not only about transactions of “official” personal business and formal activity, but are also a most prevalent source of commentary on daily and personal life and relationships, almost by their very nature.[23]

In “Evidence of Me,” McKemmish states that “recordkeeping is a ‘kind of witnessing’. On a personal level it is a way of evidencing and memorialising our lives – our existence, our activities and experiences, our relationships with others, our identity, our ‘place’ in the world.”[24] According to McKemmish, the personal archive’s capacity to witness relies on the systematic way in which the creator preserves and organizes the records.[25] Harris, however, questions this emphasis on the archive’s systematization and functionality, arguing that focusing on the functionality of a personal archive may privilege evidence over other dynamics in the archive.[26] This problematization of personal archives, and what they can or cannot be, is also raised by Douglas and Mills[27] and Hobbs,[28] who have considered in depth how personal archives have been defined and point out that they are often defined less by what they are than by what they are not. McKemmish and Piggott favour an expansive view and define personal archives as including

all forms, genres, and media of records relating to that person, whether captured in personal or corporate recordkeeping systems; remembered, transmitted orally, or performed; held in manuscript collections, archival and other cultural institutions, community archives, or other keeping places; or stored in shared digital spaces.[29]

McKemmish’s important work on personal recordkeeping as a form of witnessing intersects with recent work on victims and victimhood in contexts of mass atrocities, where documentation is often a site for negotiating power and an instrument for structuring relationships between citizens and the state.[30] This research shows how victims of atrocities carry papers to substantiate the crimes and demand accountability, but these papers of victimhood also serve as sites of memorialization and ritual. Personal collections restructure victims’ relationships with their own histories and the state.[31]

Riaño-Alcalá and Baines examine multiple strategies of memory making where an individual or collective “creates a safe social space to give testimony and re-story past events of violence or resistance.”[32] Their work problematizes what we traditionally think of as evidence, documentation, or witnessing and considers instead the alternative ways in which groups adopt remembering practices in the forms of songs, poetry, dances and other performances, embodied practices, and places. Other practices that record atrocities and openly denounce the state are in the form of artwork such as woodcuttings or textiles. The best-known example of the latter is perhaps the arpilleras adopted around Latin America, from Chile to Mexico.[33]

Flinn and Alexander have defined this practice as activist archiving, relevant for people who might not identify first and foremost as archivists but who see archiving as an integral part of their activism.[34] These practices have given birth to community, organizational, and personal archives. Giraldo and Tobón analyze two personal archives, those of Fabiola Lalinde and Mario Agudelo, in the context of Colombia’s internal conflict. They explore how these two personal human rights archives interact with TJ mechanisms, producing a virtuous cycle where both archives “preceded and prepared the implementation of transitional justice mechanisms in Colombia and have provided evidence for trials and reparation processes. In turn, transitional institutions have enhanced the public recognition of these archives as paradigmatic examples of memory initiatives of the civil society.”[35]

The important work of Ludmila Da Silva Catela on the material dimension of memory in cases of disappearances in the Southern Cone is relevant here and an important inspiration for our work, as she highlights how records such as photographs of the disappeared are registers of juridical and historical truth as well as tools for their search and memorialization. The powerful symbolism and legacy of the photographs of the disappeared have been analyzed by several authors.[36]

However, the role of personal archives in contexts of enforced disappearances has been rather overlooked, despite its growing importance.[37] Personal archives play a particularly crucial role for the families of the disappeared, who have no sources of information about what happened to their loved ones except the documentation and knowledge they themselves hold, preserve, and share. Bermúdez Qvortrup has introduced the concept of archives of the disappeared to theorize and recognize the documentation practices of the families: the creation of evidence (legal and historical), memorialization, activism, and intimacy, all of which interact and depend on one another.[38]

In this article, we present an in-depth look at one of these archives of the disappeared and consider the case as an example of LMW. As Gould and Harris explain, the term memory work is often used in the contexts of TJ to explore, engage, and use memory “in endeavours to reckon with past human rights violations, injustices, violent conflict or war.”[39] LMW responds as a call to justice that honours lost lives, problematizes power, strives to create a shared future for the descendants of victims and perpetrators, and makes “space for ‘other’ voices.”[40] LMW processes are initiated from below by civil society, are usually inter-generational, and do not depend on state intervention. In this context, LMW represents an instinct for survival, working against oblivion, but also an act of love. Douglas and Alisauskas’s work on recordkeeping as an act of love is poignantly relevant; they write about how the personal records of grieving families are not only evidence of what has happened but also proof of the lives lived – and proof that their loved ones were and still are deserving of love. They are proof of emotional and intimate relationships.[41]

As we will show, this becomes particularly relevant in a context in which enforced disappearances continue and mourning is impossible because the bodies are absent and, in their place, a void and uncertainty have been installed.

Exploring Jorge’s Archive

The folder that Martha shared with us in November 2021, and which she often carries with her, begins with Jorge’s photograph (figure 1), which Martha calls “photo one thousand” (la foto mil) because it is a copy of a copy, and so on. She wishes she had the original.[42] Second comes his birth certificate, followed by a personal profile of Jorge. The creation of personal profiles has become a common practice for the families, informed by NGOs or family organizations (FOs), to lay out what they know about the events leading up to the disappearances, describe the disappeared people’s physical appearance and other characteristics, and give short profiles of their lives. When asked by the Association of Disappeared Detained Relatives (Asociación de familiares de detenidos desaparecidos, or ASFADDES) to prepare a profile of Jorge, Martha decided to adopt Jorge’s voice, to reincarnate him. Written in the first person, the profile reads as if Jorge were speaking to the reader from the unknown. The document begins, “From June 20, 1961, I have lived in my country (Colombia). I was born after two older brothers. I was always a serious child and a good student; since I was very young, I liked to sing.”[43] In Martha’s words, Jorge tells us about his childhood and teenage years, his coming of age and habits: “I loved Latin America and the Bolivarian dream, and therefore I participated in the Comité de Solidaridad con Nicaragua y El Salvador. I read Marx and Engels, but I never stopped being cheerful, a dancer, a bad drinker, a clown, a ladies’ man and a good friend.” The document describes how and why Jorge became interested in politics and his years of political activism, and it ends,

After the civic strike, the repression didn’t wait; many were detained, the threats increased, but leaving was not an option: “They will never kick me out of my country.” Enforced disappearance always horrified me because I knew what awaited me. . . .

The 15th of July, 1985, I left for Bogotá and never arrived. . . .

Today, my family (my brother, nephews, nieces, daughter, father, mother, and sister) rebuild my life, my short life of 24 years and the 14 years that my family, my political party, and my pueblo have been searching for me. Jorge Enrique Soto Gallo. Written by Martha Elizabeth Soto – proudly Jorge’s sister.

Other records include Jorge’s certificate of participation and membership in the Colombian Communist Youth (Juventud Comunista Colombiana, or JUCO) and Jorge’s UP membership certificate. It states, “He was an outstanding young patriot. He disappeared 15th of July, 1985, the year in which the plan of extermination against the members of the UP was initiated.”[44] These two documents were expedited in 2017, not only decades after the disappearance but also after the 2016 peace process.

figure 1

Foto mil (Photo one thousand). The photograph is used to represent Jorge in public spaces.

A predominant section of the archive is communication between Martha and different state authorities from 1990 to 2021. The communication starts in the 1990s because, as Martha explains, during the 1980s, no documentation was given to the families who tried to report disappearances to the authorities.[45] The first letter with Jorge’s name is sent by ASFADDES, the first association of families of disappeared persons in Colombia, to the procurator of human rights on behalf of 10 victims of disappearances. It enquires about any updates on the investigations and requests information from the state, as none had been given up to that date. These first documents are all attempts to register the disappearance with the state – to communicate with the state. It is only in 1996, more than 10 years after the disappearance, that Martha receives her first reply from the state: an official document declaring the registration of Jorge’s case open with a case number. From then on, Martha writes directly to the prosecutor’s office, the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (National Institute of Forensic Medicine), the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (National Centre for Historical Memory), the Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (Victim’s Unit), and the Registraduría Nacional del Estado Civil (National Registry Office) requesting information regarding the status of Jorge’s case and inquiring whether an investigation has been opened or the body found. The answers are either negative or evasive or ask Martha to supply more information. In 1999, Martha receives a letter stating that she has to make another official missing person’s report, this time with the prosecutor’s office.

The correspondence is made up of 23 letters in total. They include a 2015 resolution by the Victim’s Unit that registers Martha not only as a victim of forced disappearance (through her brother) but also as a victim of death threats and forced displacement in 2000.

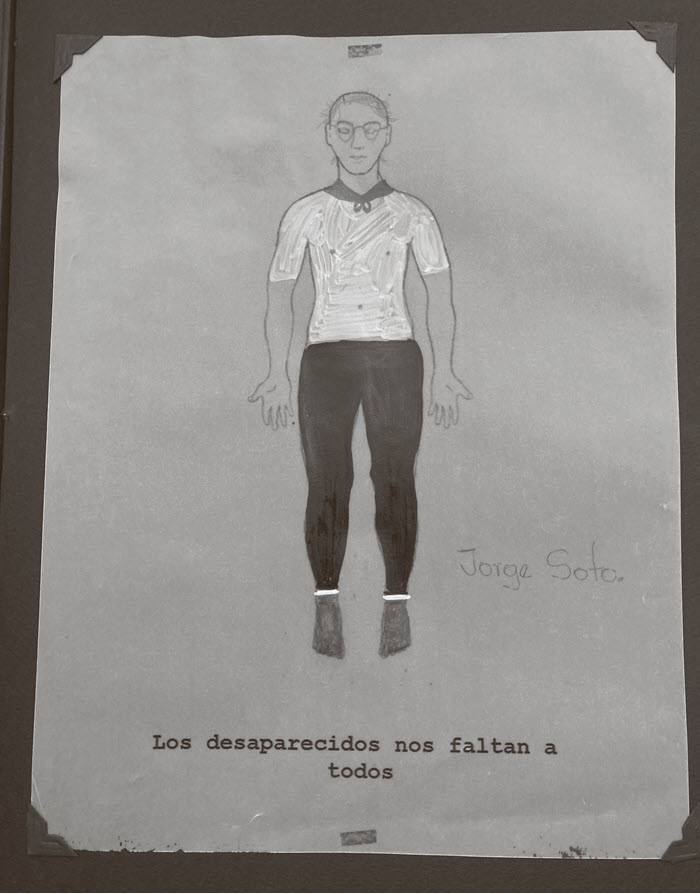

Toward the end of the folder is a certificate of Martha’s blood sample, which could potentially identify Jorge’s body (if found), a series of Martha’s fingerprints, a photocopy of Jorge’s Colombian identity card, and a series of photographs – of Jorge as a child with his family and as a youngster, as well as, more recently, of the family without Jorge.[46] The archive ends with Martha’s drawing of her brother (figure 2).

There are many documents Martha wishes were in the archive, including some crucial items that she lent for exhibitions, which were lost, and a large selection she had to abandon back in Medellín when she was forced to move due to persecution.

Seeking Answers to Fill a Void

In cases of the disappeared, we are faced with absent bodies, impossible mourning, and continued terror. Faced with the tragedy of senseless absence, families find their histories penetrated by horror, and the search begins. In Jorge’s case, as in most cases, the search for truth and justice has been in vain: the body has not been found and the perpetrators have not been identified, much less prosecuted. The act remains unpunished.

Bureaucratic Interactions and Performances

Families have learned to use the language of bureaucracy to demand attention from the state through its own formulas. This is how Martha’s archive begins. As she states, she creates a memorandum, “like at work,” to prove and evidentiate every action, interaction, reply, achievement, and failure of this search process – to register the real-life activity of her search. Martha points out that this was not a practice anyone taught her but that she and other family members “picked it up on their own,” “learning from experience.” This experience has involved a collective learning curve. Of the families, she says, “We got together and told each other we had to save everything, even the envelopes,” and laughs. “It is as if, if you have no folder, you have no disappeared.”[47]

figure 2

Jorge, illustrated by Martha as part of Entre nombres sin cuerpo: La memoria como estrategia metodológica para la acción forense sin daño en casos de desaparición forzada, a research project by Andrea Romero, 2019.

When she started, there were no central authorities that dealt with the crime of disappearances, so there was no way of registering the disappearance. The bureaucratic insistence on having things in writing has meant that the production of paperwork is about more than simply content but is also about the practices and actions of the state and their instrumentality.[48] The registration of a disappearance, which would have created evidence of the claim for Jorge’s disappearance, was not possible until the state created the required office. The first bureaucratic letter Martha received in 1996, after 10 years of silence, finally provided written proof of the presence of the state and its position regarding this crime – its refusal to investigate and decision to declare Jorge’s case closed.

In Colombia, the bureaucracy that has been created to attend to the victims is as complex as the internal armed conflict that has caused the damage. Since 2000, when forced disappearance was recognized in the country’s legislation as a crime, countless measures have been enacted, and from them have emerged procedures, formats, and records, which, rather than creating possibility, represent obstacles to accessing truth and justice. The government engages with its citizens by producing bureaucratic forms and papers, and thus, those seeking to interact with the state must mimic this process to a certain extent, in the form of petitions, letters, forms, and so on.[49] The families must run around in bureaucratic circles to comply while the government can carry out incumplir cumpliendo (complying incompliantly),[50] “the practice of not fulfilling the promises of public policy while generating a discourse (and bureaucratic apparatus) that performs fulfillment.”[51]

Jorge’s archive is made up of the residue left by bureaucratic performances and the logic of questions and answers. Martha petitions a number of agencies for information: the attorney general, the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (National Institute of Forensic Medicine), the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (National Centre for Historical Memory), the Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (Victim’s Unit), the Registraduría Nacional del Estado Civil (National Registry Office), and the Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas Dadas por Desaparecidas (Search Unit for Disappeared Persons, UBPD). The petitions embody Martha’s strenuous efforts to bring her brother out of the absolute horror of disappearance. They are made “due to the need of a sister,” “on behalf of the family,” and to obtain information on “the current state of the process.”

The state answers in refusals and delays: “The delegate attorney for the defence of human rights decided to refrain from ordering the formal opening of a disciplinary investigation and therefore to file the aforementioned diligence”; “So far no positive results have been achieved”; “The investigation is suspended.”[52] For almost 40 years, Martha searches in vain for answers. Refusals, delays, take the place of meaning, of truth. Deep down, she senses that there are no answers, but she persists. She petitions them again: “Atentamente me dirijo a ustedes” (I address you cordially).

We see in these official replies to Martha’s enquiries the “morass of governmental bureaucratic inaction”:[53]

empty gestures, with committees that never meet and offices that are never staffed, with zero budget allocations or no actual programs. In other cases, staff and budget are entirely absorbed in the production of bureaucratic procedures, protocols, and physical infrastructure, only to be dismantled and reassembled with changing political winds, a new president, minister, or director. Exemplified by the expanding thicket of redundant bureaucracies, initiatives, commissions, committees, decrees, and programs, with little coordination and less institutional memory, the production of impunity is the result of a shell game of shifting responsibilities.[54]

The trauma of the disappearances, along with the actions that must be deployed in the search process, cause the collapse of the world the families knew before. Relatives often lose confidence in the state that denies, that is complicit in or guilty of the act, that leaves them alone in the search process. Paradoxically, it is precisely this bureaucratic world that constitutes the basis for designing the itinerary of actions, performative strategies, and tactics the relatives use to seek answers. Relatives appeal to the authorities, to the organs of the judiciary, to politicians, and to journalists. The archive, full of questions and petitions to the state and its officials, is created to officialize and communicate an information need, thereby evidentiating the crime.

Evidence of a Person and a Life

Public and personal meanings associated with the disappeared are displayed through relatives’ appeals for the truth: the banners with photos, political slogans, and rituals express the absence of the body and insist on pointing out this absence. The agency of relatives, according to Veena Das, begins with “a descent into the ordinary world but as if in mourning for it. Recovery did not lie in enacting a revenge against the world, but in inhabiting it in a gesture of mourning for it.”[55]

Within the cracks among the bureaucratic forms, we find the sensitive remains of humanity. Jorge is at the centre of each document. Even the certificate of Martha’s blood sample and fingerprints was created for the purpose of finding Jorge, who is revealed with each document, as with consecutive brushstrokes uncovering an archaeological dig, as more than a name. We find the place and name of the hospital he was born in, his parents and siblings’ names. We learn about how he grew up, went to school, sang, had friends and lovers. In the photographs provided, he stares at us as a child among his siblings, his mother holding him in her arms. All these traces constitute a testimony of a family unit and of a loved member of a community. This life and absence, love and loss, are exhibited in the archive as Martha places two photographs side by side: in one, her family is together and complete – two adults and four children – and in another photograph of the same family, taken years later, the absence of Jorge is visible. Martha visualizes his absence.

In her profile of Jorge, Martha appeals to the imagination to fill the void; she re-enacts Jorge to give him a voice beyond the unknown. She links Jorge to his own history and to the family of which he was a part. She makes sense of his life and signs the profile at the end, emphasizing her pride in being her brother’s sister.

Jorge’s photograph has been used to demand answers, to raise awareness about his case and memorialize his life, and to recognize his individuality in a mass of indicators and statistics. Martha has put Jorge’s face in every space she has access to, in every exhibition she can participate in, in the press, and on websites. His images help to confront “the collective categories of ‘disappeared’, ‘assassinated’ or simply ‘dead’ (which encompasses all individualities without distinction of sex, age, temperament, path in life). They allow an individual existence, a biography, to be shown.”[56] The photographs, as Cieplak explains, are both “pragmatic tools in the search . . . and . . . powerful symbols.”[57]

The persistence in Martha’s correspondence, her family pictures, her incarnation of Jorge in the profile, and a pencil drawing of her brother not only provide evidentiary proof of her and her family’s relationships to Jorge but also imbue the records with feelings that “are central to their meaning and ongoing significance.” As “an act of love,” the recordkeeping is Martha’s way of staying connected to Jorge, continuing her relationship with him, and keeping him connected to the family.[58]

Evidence of a loss becomes evidence of a life. This evidence reflects and articulates a particular context – a society and a culture that continues to criminalize expressions of alternative politics. Jorge’s disappearance, the loss of another young person with political ideals and ambitions, was meant to send a message of terror to an entire generation of potential political leaders within the UP before exterminating it. Nevertheless, the traces of Jorge’s political life and interests have not been hidden or shamefully forgotten but, on the contrary, have been petitioned for and certified, as Martha continues Jorge’s social and political presence.[59] Martha is one of many family members who keep the UP’s presence in the public sphere through performances, exhibitions, protests, and participation in the TJ process. They now use their knowledge and years of experience on the front line to memorialize and demonstrate the state’s crimes and impunity.

The archive depicts the changes that have occurred in Colombia during Martha’s search. Martha explains that the recent taking of blood samples and fingerprints to help identify Jorge for her was unprecedented and would not have happened some years ago. The fact that today there might be the possibility of identifying the body, if the body is ever found, gives Martha hope – the hope of knowing Jorge’s fate.[60]

The documents also show remnants of other searches by other families: the first letter to the state, with the names of nine more disappeared people alongside Jorge’s; the work being done by different NGOs and FOs to assist families; and the newspaper articles and records from protests show that Martha is part of a larger community, with the same goals and expectations. Martha’s collection, even on its own, gives us a picture of the social situation and demonstrates that she is not alone in Colombia in her activist archiving.

This is an unintentional archive, in that Martha’s purpose was never to go out and create an archive, but rather, to collect every trace of her brother to give testimony of his life and his disappearance against the denial of the state. That intensive, existential, and instinctive collecting process became, in time, an “intentional archive,”[61] as Martha realized that the process and its materiality filled a void by bringing back his memory and giving her something physical to hold on to.[62]

Liberatory Memory Work

The peace agreement signed between the state and the FARC guerrillas in 2016, despite the deficiencies in its implementation, has meant hope for many victims. A comprehensive system of truth, justice, and reparation has been created, and there have been guarantees of non-repetition, including the JEP, the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-repetition (CEV), and the UBPD. This new institutional framework creates a space in which “the public recognition of pain can allow the creation of new opportunities to resume daily life.”[63] Within this space and these new possibilities, families such as Martha’s have engaged in the public sphere of “dealing with the past” on their own terms.

The concept of LMW acknowledges the important recordkeeping practices that families have been doing for decades, of which Martha’s archive is an example. LMW includes teaching these practices to other families. This work of preserving and creating documents found nowhere else often occurs on the margins and in private and is subject to risk and undervalued. Families like Martha’s have made the long-term commitment to demand a transformation of society[64] out of their private pain. From the privacy of the home, records from Jorge’s archive have made their way into a “collective corpus belonging to all those concerned with the problem of disappearance.”[65] They are the foundation of Martha’s political action. They become part of the broad umbrella of human rights archives, quietly joining in from below. And yet, they may not always make it to the public sphere. Fear, intimidation, and a culture of violence and retribution can make families hesitant regarding the publicity of these records. Martha tells us that

People can be afraid of learning these information practices; they can fear how difficult it can be keeping papers. Some prefer to have them kept for them in an office or institution – professionally. But Movimiento Nacional de Víctimas de Crímenes de Estado [MOVICE, the organization she helps run] teaches the importance of keeping these documents at home as well as in an office or professionally – the importance of copies. Many organizations have experienced violence and threats, and some have been left without documentation. In terms of documentation, we are learning, and we are teaching.[66]

Beyond TJ

One problem with TJ mechanisms, as described by Stockwell, is that they do not always bring about the reconciliation they promise. For example, after decades of mechanisms “dealing with” and “working through” the legacy of violence in that country, “Argentine memorial cultures appear beholden to the entrenched political and ideological divisions of old.”[67] Questions about the disappeared still prevail, with no answers from the security forces, and most families know nothing about their loved ones’ whereabouts. In Argentina, women’s testimonies demonstrate how memories of trauma persist despite public truth-telling and “the finality that the concepts of truth and justice are supposed to deliver.”[68] Stockwell explains how oral testimonies of violence can potentially contribute to the ongoing polarization of a society.[69] In societies such as Colombia’s, where atrocities have been perpetrated by different actors and social trauma persists in daily life, political polarization, social stigmatization, and divergent discourses often lead to an absence of empathy.

Personal archives such as Martha’s respond to injustice by “highlight[ing] the complexity . . . between violence, power and affect,”[70] and we would argue that personal archives such as Martha’s do this well, as they are not about “moving on” but about capturing their affect in a context – through a variety of records that evidentiate and memorialize lives lost. These archives help find “non- reductive ways of thinking about memory in a society recovering from violence and trauma.”[71]

Humanizing Practices amid Inhuman Practices

Even though these personal collections have become a way for families to participate in healing processes in private and on their own terms, there are many silences in these archives. As Tate has described in Counting the Dead, much of the political work of families consists of “ephemeral encounters that rarely leave any written records.”[72] They are carried in memory or in the body but are not in the archive.[73] However, as seen here, these archives did not start as ends in themselves but as means to an end: the demand for justice. In the process, spurred by hope and new ways of truth-telling, and influenced by TJ mechanisms, this recordkeeping culture has emerged as we have shown. Yet, the emergence of this culture is also due to recordkeepers’ gradual realization of the power of the artifactual and materiality. As Anneli Sundqvist reminds us, “Not the least is it the (once) bodily closeness to someone or something, or the physical presence in a situation at some moment in time (which as such are material phenomena), that evokes emotions and activity and mediates relations.”[74] In this context, the materiality of the records is enhanced not only by Martha and Jorge’s uses of the objects but also through the emotions they evoke and the symbolic representation they obtain[75] for both Jorge’s family and an entire community made up of other families of disappeared. As Sundqvist explains, objects affect people and “do so by merely being objects.”[76] This materiality is important to highlight as Martha tells us that more families in Colombia are keeping records digitally because they feel it is safer and because many official documents are sent digitally. Nevertheless, Martha believes these “younger families” are missing out on the therapeutic element of having a physical folder to hold and take with them to be immediately accessed and displayed. After all, this is how much of the politicalTactivism and networking in Colombia still occurs: face-to face. Material records can be “‘a point of departure’ for production, that is, for action and agency and a course of events.”[77] Martha hopes her children will continue her work and add to the archive, as this is the only thing of value she is leaving them.[78]

Seeing Martha’s archival practice as LMW identifies the personal and familial endeavour of this labour and its repercussions, which goes beyond a violation-specific focus.[79] It enables us to look at wider causes of suffering and their consequences, revealing how families like Martha’s are hardly passive, but are instead resilient, active liberatory memory workers for their communities, undertaking humanizing practices amid inhuman practices.[80] They are reincorporating the disappeared back into the social fabric so as to not condemn them to oblivion,[81] while at the same time moving beyond “the uncritical assumption that testimony work is both healing and socially transformative.”[82]

The families are not formal archivists, but by learning the trade, they are becoming grassroots recordkeepers out of an instinct of preservation and care for themselves and their loved ones. As Martha’s memory work shows, this instinct is also based on the impulse to preserve “other” narratives of alternative political inclinations, something Colombia lacks, and to make sense of that which has none.

Where Do We Go from Here?

We introduce this case to highlight a recordkeeping practice that, in the words of Scott’s book Weapons of the Weak, is one of many “forms of resistance that reflect the conditions and constraints under which they are generated.”[83] It is also a humanizing process. These collections work as direct resistance – as legal papers in official investigations, recording the evidence that is later needed to identify bodies, publicly shaming the state – or as indirect resistance, through the memorializing, loving, and daily active remembering of the disappeared. It is precisely when focusing on the personal dimension that we begin to understand the importance of the materiality of these collections, which goes beyond evidence as an issue of justice to act also as an instinct against oblivion for people who, although missing, are still loved.

These collections live, like their creators, in a state of vulnerability and uncertainty and thus, by implication, the evidence and memory of the disappeared persons are also vulnerable and uncertain. This raises practical, ethical, emotional, and political questions[84] regarding who should store these collections, and how, if they are to be donated or shared in a country with low levels of trust, transparency, and stability. Hamber and Kelly have raised these questions in relation to Northern Ireland, where “story gathering has been limited as a result of the contested nature of politics and competing narratives.”[85] Yet these collections are more than just testimonies; they are collections of bureaucratic, emotional, personal, and historical traces that together bear witness to lives lost and all the social and personal reverberations of these events. These are questions that the archival profession can assist in answering only if and when there is a solid understanding of the social vulnerabilities of each victim’s specific society and case of enforced disappearance. Because the archival profession and archival studies are concerned with the long-term preservation of materials and their narratives in context, we have the capability of looking at these archives beyond transitional justice normativity – that is, of looking beyond “arbitrary time limits on memory”[86] imposed on them, to look at the life of the records, from archivalization to uses and preservation. More research is needed in archival studies on the role of archives in contexts of enforced disappearance. There is much this context can teach us about centring people, even when they are missing.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup is a PhD candidate in Archival, Library and Information Science at Oslo Metropolitan University in Norway. She has an MA in Theory and Practice of Human Rights from the University of Essex in England, a BA in Library and Information Science from Oslo Metropolitan University, and a BA in Humanities from the University of Essex.

Marta Lucía Giraldo has a PhD in Comparative, Political and Social History from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and a master’s degree in Colombian Literature and a history degree from the Universidad de Antioquia. She is a full professor at the University of Antioquia, where she teaches courses on the relationship between archives and society and research in archival science. Her research interests include personal and community archives, the relationship between archives and memory, and the study of archives from a rights-based approach. She is a member of Archiveros sin Fronteras.

Notes

-

[1]

We would like to thank Anneli Sundqvist, Jemima García-Godos, and Daniel Jerónimo Tobón for their very helpful feedback, insights, and proofreading. We are enormously grateful to Martha Soto Gallo for her time, patience, and kindness in sharing not only her story and words but also her personal documentation.

-

[2]

Andrei Gomez-Suarez, Genocide, Geopolitics and Transnational Networks: Con-Textualising the Destruction of the Unión Patriótica in Colombia (London: Routledge, 2015), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315765020.

-

[3]

Around 100,000 people have been forcibly disappeared in Colombia in the last 50 years, in the context of the internal armed conflict. A lack of clear and reliable data, divergent figures, and little progress in the investigations are evident in the inactive cases and absence of convictions. See Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas Dadas por Desaparecidas, “Así avanza la búsqueda de las personas desaparecidas en Colombia,” UBPD, accessed December 10, 2021, https://ubpdbusquedadesaparecidos.co/actualidad/cifras-busqueda-desaparecidos-colombia/.

-

[4]

Martha signed an informed consent form, and the research for this paper was approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data and Oslo Metropolitan University in Norway.

-

[5]

Martha Soto Gallo, interview with authors, January 18, 2022.

-

[6]

Jennifer Douglas and Alexandra Alisauskas, “‘It Feels Like a Life’s Work’: Recordkeeping as an Act of Love,” Archivaria 91 (Spring/Summer 2021): 6–37.

-

[7]

Jennifer Douglas, Alexandra Alisauskas, and Devon Mordell, “‘Treat Them with the Reverence of Archivists’: Records Work, Grief Work, and Relationship Work in the Archives,” Archivaria 88 (Fall 2019): 84–120.

-

[8]

Chandre Gould and Verne Harris, Memory for Justice (Johannesburg: Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2014), 4, https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/MEMORY_FOR_JUSTICE_2014v2.pdf. Since then, several other authors have developed and expanded the concept of liberatory memory work, e.g., Michelle Caswell, Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work (London: Routledge, 2021); Michelle Caswell, “Feeling Liberatory Memory Work: On the Archival Uses of Joy and Anger,” Archivaria 90 (Fall 2020): 148–64; Kirsten Wright and Nicola Laurent, “Safety, Collaboration, and Empowerment: Trauma-Informed Archival Practice,” Archivaria 91 (Spring/Summer 2021): 38–73, https://doi.org/10.7202/1078465ar; Gabriel Solis, “Documenting State Violence: (Symbolic) Annihilation & Archives of Survival,” KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies 2, no. 1 (2018): 1–11.

-

[9]

UN Human Rights Commission, “International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, December 23, 2010, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-convention-protection-all-persons-enforced. See also UN General Assembly, International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, A/RES/61/177 (January 12, 2007), https://treaties.un.org/doc/source/docs/A_RES_61_177-E.pdf; UN General Assembly, Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, A/RES/47/133 (February 12, 1993), https://www.refworld.org/docid/3dd911e64.html.

-

[10]

Comité de Solidaridad con los Presos Políticos, Libro negro de la represión: Frente Nacional 1958–1974 (Bogotá: Gráficas Mundo Nuevo, 1974).

-

[11]

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Huellas y rostros de la desaparición forzada (1970–2010), vol. Tomo II (Bogotá: CNMH, 2013).

-

[12]

Gomez-Suarez, Genocide, Geopolitics and Transnational Networks.

-

[13]

Andrei Gomez-Suarez, “Perpetrator Blocs, Genocidal Mentalities and Geographies: The Destruction of the Union Patriótica in Colombia and Its Lessons for Genocide Studies,” Journal of Genocide Research 9, no. 4 (2007): 640, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520701644440.

-

[14]

Gomez-Suarez, 640.

-

[15]

Gomez-Suarez, Genocide, Geopolitics and Transnational Networks.

-

[16]

Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, “Victimización de miembros de la Unión Patriótica,” No. AUTO No. 27 de 2019 (Bogotá: Sala de Reconocimiento de Verdad, de Responsabilidad y de Determinación de los Hechos y Conductas, February 26, 2019).

-

[17]

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Todo pasó frente a nuestros ojos. El genocidio de la Unión Patriótica 1984–2002 (Bogotá: CNMH, 2018).

-

[18]

Gomez-Suarez, Genocide, Geopolitics and Transnational Networks.

-

[19]

Gomez-Suarez, Genocide, Geopolitics and Transnational Networks; Leah Carroll, Violent Democratization: Social Movements, Elites, and Politics in Colombia’s Rural War Zones, 1984–2008 (Paris: University of Notre Dame Press, 2011).

-

[20]

Gomez-Suarez, Genocide, Geopolitics and Transnational Networks, 1–2.

-

[21]

Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, “Victimización de miembros de la Unión Patriótica,” 30.

-

[22]

Caroline Williams, quoted in Jennifer Douglas and Allison Mills, “From the Sidelines to the Center:

Reconsidering the Potential of the Personal in Archives,” Archival Science 18, no. 3 (2018): 258, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-018-9295-6.

-

[23]

Catherine Hobbs, “The Character of Personal Archives: Reflections on the Value of Records of Individuals,” Archivaria 52 (Fall 2001): 127.

-

[24]

Sue McKemmish, “Evidence of Me,” Australian Library Journal 45, no. 3 (1996): 175, https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.1996.10755757.

-

[25]

McKemmish, 175.

-

[26]

Verne Harris, “On the Back of a Tiger: Deconstructive Possibilities in ‘Evidence of Me,’” Archives and Manuscripts 29, no. 1 (2001): 12.

-

[27]

Douglas and Mills, “From the Sidelines to the Center.”

-

[28]

Hobbs, “The Character of Personal Archives.”

-

[29]

Sue McKemmish and Michael Piggott, “Toward the Archival Multiverse: Challenging the Binary Opposition of the Personal and Corporate Archive in Modern Archival Theory and Practice,” Archivaria 76 (Fall 2013): 113.

-

[30]

Kate Cronin-Furman and Roxani Krystalli, “The Things They Carry: Victims’ Documentation of Forced Disappearance in Colombia and Sri Lanka,” European Journal of International Relations 27, no. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120946479.

-

[31]

Cronin-Furman and Krystalli, 4.

-

[32]

Pilar Riaño-Alcalá and Erin Baines, “The Archive in the Witness: Documentation in Settings of Chronic Insecurity,” International Journal of Transitional Justice 5, no. 3 (2011): 412.

-

[33]

Dr. Marjorie Agosín, “Stitching Resistance: The History of Chilean Arpilleras” (presentation, National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum, Albuquerque, NM, October 19, 2012), https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/laii_events/19; Jhonny Pacheco, “Las arpilleras de Shuba: Bordado de arpilleras para tejer la memoria colectiva sobre los espacios,” Revista Cambios y Permanencias 9, no. 1 (2018): 1009–28; Isabel González, “Repositorio digital para la documentación de textiles testimoniales del conflicto armado en Colombia” (Tesis de maestría, Universidad de Antioquia – Escuela Interamericana de Bibliotecología, Medellín, 2019).

-

[34]

Andrew Flinn and Ben Alexander, “‘Humanizing an Inevitability Political Craft’: Introduction to the Special Issue on Archiving Activism and Activist Archiving,” Archival Science 15, no. 4 (2015): 329–35, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9260-6.

-

[35]

Marta Lucía Giraldo and Daniel Jerónimo Tobón, “Personal Archives and Transitional Justice in Colombia: The Fonds of Fabiola Lalinde and Mario Agudelo,” International Journal of Human Rights 25, no. 3 (2020): 529, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1811691.

-

[36]

Ludmila Da Silva Catela, No habrá flores en la tumba del pasado (La Plata: Al Margen, 2001); Natalia Fortuny, “Memoria fotográfica. Restos de la desaparición, imágenes familiares y huellas del horror en la fotografía argentina posdictatorial,” Amerika. Mémoires, identités, territoires 2 (2010), https://doi.org/10.4000/amerika.1108; Deborah Poole and Isaías Rojas Pérez, “Memorias de la reconciliación: Fotografía y memoria en el Perú de la posguerra,” E-misférica – Revista del Instituto Hemisférico 7.2, no. Detrás / Después de la Verdad (2010): 1–23.

-

[37]

Giraldo and Tobón, “Personal Archives and Transitional Justice in Colombia.”

-

[38]

Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup, “Archives of the Disappeared: Conceptualising the Personal Archives of the Families of Disappeared Persons,” Journal of Human Rights Practice, May 16, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huac003.

-

[39]

Gould and Harris, Memory for Justice, 2.

-

[40]

Gould and Harris, Memory for Justice, 5.

-

[41]

Douglas and Alisauskas, “‘It Feels Like a Life’s Work,’” 24.

-

[42]

Soto Gallo, interview, January 18, 2022.

-

[43]

Translations of this profile are by Natalia Bermudez Qvortrup, November 11, 2021.

-

[44]

Translated by Natalia Bermudez Qvortrup, November 11, 2021.

-

[45]

Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición and Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Guardianes de la memoria. Archivos y trayectorias en la construcción de memorias del conflicto en Medellín, vol. 1, Iniciativas para la Construcción de Paz: Memorias, resistencias y juventudes (Medellín, 2021), in Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Económicas, “Primer Encuentro de Iniciativas para la Construcción de Paz,” August 19, 2021, YouTube video, 3:43:09, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cJ7UIfTYKs.

-

[46]

Due to European law, we were not allowed to publish Martha and Jorge’s family photographs where third persons are present, but a video commemorating 27 years of Jorge’s disappearance includes many of the photographs in Martha’s archive and can be found here: Redacción Medellín, “Jorge Soto . . . 27 años sin olvido !!!” [Jorge Soto . . . 27 years without forgetting], July 14, 2012, YouTube video, 4:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YalC2hqI_9A&t=1s.

-

[47]

Soto Gallo, interview, January 18, 2022.

-

[48]

Akhil Gupta, Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), https://muse.jhu.edu/book/70925.

-

[49]

Gupta, Red Tape; Cronin-Furman and Krystalli, “The Things They Carry.”

-

[50]

Valentina Pellegrino, “Cifras de papel: la rendición de cuentas del Gobierno colombiano ante la justicia como una manera de incumplir cumpliendo,” Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología, no. 42 (2021): 3–27, https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda42.2021.01.

-

[51]

Roxani Krystalli, “Attendance Sheets and Bureaucracies of Victimhood in Colombia,” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, November 24, 2020, 3, https://polarjournal.org/2020/11/24/attendance-sheets-and-bureaucracies-of-victimhood-in-colombia/.

-

[52]

In order to protect Martha, these statements have been deidentified.

-

[53]

Winifred Tate, Counting the Dead: The Culture and Politics of Human Rights Activism in Colombia (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 217, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520941175.

-

[54]

Tate, 216.

-

[55]

Veena Das, Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary (London: University of California Press, 2007), 77.

-

[56]

Da Silva Catela quoted in Piotr Cieplak, “Private Archives, Public Deaths in Rwanda and Argentina: Conversations with Claver Irakoze and Ludmila da Silva Catela,” Wasafiri 35, no. 4 (2020): 11, https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2020.1800232.

-

[57]

Cieplak, 6.

-

[58]

Douglas and Alisauskas, “‘It Feels Like a Life’s Work,’” 30–31.

-

[59]

Douglas and Alisauskas, “‘It Feels Like a Life’s Work.’”

-

[60]

Soto Gallo, interview, January 18, 2022.

-

[61]

Andrew Flinn and Anna Sexton, “Activist Participatory Communities in Archival Contexts: Theoretical Perspectives,” in Participatory Archives: Theory and Practice, ed. Edward Benoit III and Alexandra Eveleigh (London: Facet Publishing, 2019), 173–90.

-

[62]

Soto Gallo, interview, January 18, 2022.

-

[63]

Arthur Kleinman, Veena Das, Deepak Mehta, Fiona C. Ross, Komatra Chuengsatiansup, Margaret Lock, Maya Todeschini et al., Remaking a World: Violence, Social Suffering, and Recovery (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 19.

-

[64]

Gould and Harris, Memory for Justice.

-

[65]

Da Silva Catela quoted in Cieplak, “Private Archives, Public Deaths in Rwanda and Argentina,” 12.

-

[66]

Martha Soto in Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Económicas, “Primer Encuentro de Iniciativas para la Construcción de Paz.”

-

[67]

Jill Stockwell, “‘The Country That Doesn’t Want to Heal Itself’: The Burden of History, Affect and Women’s Memories in Post-Dictatorial Argentina,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence 8, no. 1 (2014): 34, https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-3043.

-

[68]

Stockwell, 35.

-

[69]

Stockwell, 40.

-

[70]

Stockwell, 43.

-

[71]

Stockwell, 43.

-

[72]

Tate, Counting the Dead, 122.

-

[73]

Adriana Lalinde in Facultad de Ciencias Humanas y Económicas, “Primer Encuentro de Iniciativas para la Construcción de Paz.”

-

[74]

Anneli Sundqvist, “Things That Work: Meditations on Materiality in Archival Discourse,” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, 8 (2021): 12, https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol8/iss1/7.

-

[75]

Sundqvist, “Things That Work.”

-

[76]

Sundqvist, “Things That Work,” 14.

-

[77]

Sundqvist “Things That Work,” 12.

-

[78]

Soto Gallo, interview, January 18, 2022.

-

[79]

Brandon Hamber and Gráinne Kelly, “Practice, Power and Inertia: Personal Narrative, Archives and Dealing with the Past in Northern Ireland,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 8, no. 1 (2016): 25–44, 28, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huw001.

-

[80]

Maria Victoria Uribe Alarcón, “Against Violence and Oblivion: The Case of Colombia’s Disappeared,” in Meanings of Violence in Contemporary Latin America, ed. Gabriela Polit Dueñas and María Helena Rueda (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 37–52.

-

[81]

Uribe Alarcón, 50.

-

[82]

Wiene cited in Hamber and Kelly, “Practice, Power and Inertia,” 28.

-

[83]

James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), 242.

-

[84]

Hamber and Kelly, “Practice, Power and Inertia,” 35.

-

[85]

Hamber and Kelly, 35.

-

[86]

Brison quoted in Stockwell, “‘The Country That Doesn’t Want to Heal Itself,’” 43.

List of figures

figure 1

figure 2

Jorge, illustrated by Martha as part of Entre nombres sin cuerpo: La memoria como estrategia metodológica para la acción forense sin daño en casos de desaparición forzada, a research project by Andrea Romero, 2019.